"Budući da borba da postanemo emancipirani subjekti nije uspjela, kako bi bilo da, za promjenu, pređemo na stranu objekata [to je već bio predlagao i Baudrillard)? Zašto ne bismo bili stvari, objekti bez subjekata, stvari među drugim stvarima, objekti koji osjećaju?"

Amen.

A Thing Like You and Me:

(...) as the struggle to become a subject became mired in its own contradictions, a different possibility emerged. How about siding with the object for a change? Why not affirm it? Why not be a thing? An object without a subject? A thing among other things? “A thing that feels” (...)

In Defense of the Poor Image

Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?

Marvin Jordan I’d like to open our dialogue by acknowledging the central theme for which your work is well known — broadly speaking, the socio-technological conditions of visual culture — and move toward specific concepts that underlie your research (representation, identification, the relationship between art and capital, etc). In your essay titled “Is a Museum a Factory?” you describe a kind of ‘political economy’ of seeing that is structured in contemporary art spaces, and you emphasize that a social imbalance — an exploitation of affective labor — takes place between the projection of cinematic art and its audience. This analysis leads you to coin the term “post-representational” in service of experimenting with new modes of politics and aesthetics. What are the shortcomings of thinking in “representational” terms today, and what can we hope to gain from transitioning to a “post-representational” paradigm of art practices, if we haven’t arrived there already?

Hito Steyerl Let me give you one example. A while ago I met an extremely interesting developer in Holland. He was working on smart phone camera technology. A representational mode of thinking photography is: there is something out there and it will be represented by means of optical technology ideally via indexical link. But the technology for the phone camera is quite different. As the lenses are tiny and basically crap, about half of the data captured by the sensor are noise. The trick is to create the algorithm to clean the picture from the noise, or rather to define the picture from within noise. But how does the camera know this? Very simple. It scans all other pictures stored on the phone or on your social media networks and sifts through your contacts. It looks through the pictures you already made, or those that are networked to you and tries to match faces and shapes. In short: it creates the picture based on earlier pictures, on your/its memory. It does not only know what you saw but also what you might like to see based on your previous choices. In other words, it speculates on your preferences and offers an interpretation of data based on affinities to other data. The link to the thing in front of the lens is still there, but there are also links to past pictures that help create the picture. You don’t really photograph the present, as the past is woven into it.

Additionally, Ranciere’s democratic solution: there is no noise, it is all speech. Everyone has to be seen and heard, and has to be realized online as some sort of meta noise in which everyone is monologuing incessantly, and no one is listening. Aesthetically, one might describe this condition as opacity in broad daylight: you could see anything, but what exactly and why is quite unclear. There are a lot of brightly lit glossy surfaces, yet they don’t reveal anything but themselves as surface. Whatever there is — it’s all there to see but in the form of an incomprehensible, Kafkaesque glossiness, written in extraterrestrial code, perhaps subject to secret legislation. It certainly expresses something: a format, a protocol or executive order, but effectively obfuscates its meaning. This is a far cry from a situation in which something—an image, a person, a notion — stood in for another and presumably acted in its interest. Today it stands in, but its relation to whatever it stands in for is cryptic, shiny, unstable; the link flickers on and off. Art could relish in this shiny instability — it does already. It could also be less baffled and mesmerised and see it as what the gloss mostly is about – the not-so-discreet consumer friendly veneer of new and old oligarchies, and plutotechnocracies.

MJ In your insightful essay, “The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation”, you extend your critique of representation by focusing on an irreducible excess at the core of image spam, a residue of unattainability, or the “dark matter” of which it’s composed. It seems as though an unintelligible horizon circumscribes image spam by image spam itself, a force of un-identifiability, which you detect by saying that it is “an accurate portrayal of what humanity is actually not… a negative image.” Do you think this vacuous core of image spam — a distinctly negative property — serves as an adequate ground for a general theory of representation today? How do you see today’s visual culture affecting people’s behavior toward identification with images?

HS Think of Twitter bots for example. Bots are entities supposed to be mistaken for humans on social media web sites. But they have become formidable political armies too — in brilliant examples of how representative politics have mutated nowadays. Bot armies distort discussion on twitter hashtags by spamming them with advertisement, tourist pictures or whatever. Bot armies have been active in Mexico, Syria, Russia and Turkey, where most political parties, above all the ruling AKP are said to control 18,000 fake twitter accounts using photos of Robbie Williams, Megan Fox and gay porn stars. A recent article revealed that, “in order to appear authentic, the accounts don’t just tweet out AKP hashtags; they also quote philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and movies like PS: I Love You.” It is ever more difficult to identify bots – partly because humans are being paid to enter CAPTCHAs on their behalf (1,000 CAPTCHAs equals 50 USD cents). So what is a bot army? And how and whom does it represent if anyone? Who is an AKP bot that wears the face of a gay porn star and quotes Hobbes’ Leviathan — extolling the need of transforming the rule of militias into statehood in order to escape the war of everyone against everyone else? Bot armies are a contemporary vox pop, the voice of the people, the voice of what the people are today. It can be a Facebook militia, your low cost personalized mob, your digital mercenaries. Imagine your photo is being used for one of these bots. It is the moment when your picture becomes quite autonomous, active, even militant. Bot armies are celebrity militias, wildly jump cutting between glamour, sectarianism, porn, corruption and Post-Baath Party ideology. Think of the meaning of the word “affirmative action” after twitter bots and like farms! What does it represent?

MJ You have provided a compelling account of the depersonalization of the status of the image: a new process of de-identification that favors materialist participation in the circulation of images today. Within the contemporary technological landscape, you write that “if identification is to go anywhere, it has to be with this material aspect of the image, with the image as thing, not as representation. And then it perhaps ceases to be identification, and instead becomes participation.” How does this shift from personal identification to material circulation — that is, to cybernetic participation — affect your notion of representation? If an image is merely “a thing like you and me,” does this amount to saying that identity is no more, no less than a .jpeg file?

HS Social media makes the shift from representation to participation very clear: people participate in the launch and life span of images, and indeed their life span, spread and potential is defined by participation. Think of the image not as surface but as all the tiny light impulses running through fiber at any one point in time. Some images will look like deep sea swarms, some like cities from space, some are utter darkness. We could see the energy imparted to images by capital or quantified participation very literally, we could probably measure its popular energy in lumen. By partaking in circulation, people participate in this energy and create it.

What this means is a different question though — by now this type of circulation seems a little like the petting zoo of plutotechnocracies. It’s where kids are allowed to make a mess — but just a little one — and if anyone organizes serious dissent, the seemingly anarchic sphere of circulation quickly reveals itself as a pedantic police apparatus aggregating relational metadata. It turns out to be an almost Althusserian ISA (Internet State Apparatus), hardwired behind a surface of ‘kawaii’ apps and online malls. As to identity, Heartbleed and more deliberate governmental hacking exploits certainly showed that identity goes far beyond a relationship with images: it entails a set of private keys, passwords, etc., that can be expropriated and detourned. More generally, identity is the name of the battlefield over your code — be it genetic, informational, pictorial. It is also an option that might provide protection if you fall beyond any sort of modernist infrastructure. It might offer sustenance, food banks, medical service, where common services either fail or don’t exist. If the Hezbollah paradigm is so successful it is because it provides an infrastructure to go with the Twitter handle, and as long as there is no alternative many people need this kind of container for material survival. Huge religious and quasi-religious structures have sprung up in recent decades to take up the tasks abandoned by states, providing protection and survival in a reversal of the move described in Leviathan. Identity happens when the Leviathan falls apart and nothing is left of the commons but a set of policed relational metadata, Emoji and hijacked hashtags. This is the reason why the gay AKP pornstar bots are desperately quoting Hobbes’ book: they are already sick of the war of Robbie Williams (Israel Defense Forces) against Robbie Williams (Electronic Syrian Army) against Robbie Williams (PRI/AAP) and are hoping for just any entity to organize day care and affordable dentistry.

What this means is a different question though — by now this type of circulation seems a little like the petting zoo of plutotechnocracies. It’s where kids are allowed to make a mess — but just a little one — and if anyone organizes serious dissent, the seemingly anarchic sphere of circulation quickly reveals itself as a pedantic police apparatus aggregating relational metadata. It turns out to be an almost Althusserian ISA (Internet State Apparatus), hardwired behind a surface of ‘kawaii’ apps and online malls. As to identity, Heartbleed and more deliberate governmental hacking exploits certainly showed that identity goes far beyond a relationship with images: it entails a set of private keys, passwords, etc., that can be expropriated and detourned. More generally, identity is the name of the battlefield over your code — be it genetic, informational, pictorial. It is also an option that might provide protection if you fall beyond any sort of modernist infrastructure. It might offer sustenance, food banks, medical service, where common services either fail or don’t exist. If the Hezbollah paradigm is so successful it is because it provides an infrastructure to go with the Twitter handle, and as long as there is no alternative many people need this kind of container for material survival. Huge religious and quasi-religious structures have sprung up in recent decades to take up the tasks abandoned by states, providing protection and survival in a reversal of the move described in Leviathan. Identity happens when the Leviathan falls apart and nothing is left of the commons but a set of policed relational metadata, Emoji and hijacked hashtags. This is the reason why the gay AKP pornstar bots are desperately quoting Hobbes’ book: they are already sick of the war of Robbie Williams (Israel Defense Forces) against Robbie Williams (Electronic Syrian Army) against Robbie Williams (PRI/AAP) and are hoping for just any entity to organize day care and affordable dentistry.

But beyond all the portentous vocabulary relating to identity, I believe that a widespread standard of the contemporary condition is exhaustion. The interesting thing about Heartbleed — to come back to one of the current threats to identity (as privacy) — is that it is produced by exhaustion and not effort. It is a bug introduced by open source developers not being paid for something that is used by software giants worldwide. Nor were there apparently enough resources to audit the code in the big corporations that just copy-pasted it into their applications and passed on the bug, fully relying on free volunteer labour to produce their proprietary products. Heartbleed records exhaustion by trying to stay true to an ethics of commonality and exchange that has long since been exploited and privatized. So, that exhaustion found its way back into systems. For many people and for many reasons — and on many levels — identity is just that: shared exhaustion.

MJ This is an opportune moment to address the labor conditions of social media practice in the context of the art space. You write that “an art space is a factory, which is simultaneously a supermarket — a casino and a place of worship whose reproductive work is performed by cleaning ladies and cellphone-video bloggers alike.” Incidentally, DIS launched a website called ArtSelfie just over a year ago, which encourages social media users to participate quite literally in “cellphone-video blogging” by aggregating their Instagram #artselfies in a separately integrated web archive. Given our uncanny coincidence, how can we grasp the relationship between social media blogging and the possibility of participatory co-curating on equal terms? Is there an irreconcilable antagonism between exploited affective labor and a genuinely networked art practice? Or can we move beyond — to use a phrase of yours — a museum crowd “struggling between passivity and overstimulation?”

HS I wrote this in relation to something my friend Carles Guerra noticed already around early 2009; big museums like the Tate were actively expanding their online marketing tools, encouraging people to basically build the museum experience for them by sharing, etc. It was clear to us that audience participation on this level was a tool of extraction and outsourcing, following a logic that has turned online consumers into involuntary data providers overall. Like in the previous example – Heartbleed – the paradigm of participation and generous contribution towards a commons tilts quickly into an asymmetrical relation, where only a minority of participants benefits from everyone’s input, the digital 1 percent reaping the attention value generated by the 99 percent rest.

Brian Kuan Wood put it very beautifully recently: Love is debt, an economy of love and sharing is what you end up with when left to your own devices. However, an economy based on love ends up being an economy of exhaustion – after all, love is utterly exhausting — of deregulation, extraction and lawlessness. And I don’t even want to mention likes, notes and shares, which are the child-friendly, sanitized versions of affect as currency.

All is fair in love and war. It doesn’t mean that love isn’t true or passionate, but just that love is usually uneven, utterly unfair and asymmetric, just as capital tends to be distributed nowadays. It would be great to have a little bit less love, a little more infrastructure.

Brian Kuan Wood put it very beautifully recently: Love is debt, an economy of love and sharing is what you end up with when left to your own devices. However, an economy based on love ends up being an economy of exhaustion – after all, love is utterly exhausting — of deregulation, extraction and lawlessness. And I don’t even want to mention likes, notes and shares, which are the child-friendly, sanitized versions of affect as currency.

All is fair in love and war. It doesn’t mean that love isn’t true or passionate, but just that love is usually uneven, utterly unfair and asymmetric, just as capital tends to be distributed nowadays. It would be great to have a little bit less love, a little more infrastructure.

HS Haha — good question!

Essentially I think it makes sense to compare our moment with the end of the twenties in the Soviet Union, when euphoria about electrification, NEP (New Economic Policy), and montage gives way to bureaucracy, secret directives and paranoia. Today this corresponds to the sheer exhilaration of having a World Wide Web being replaced by the drudgery of corporate apps, waterboarding, and “normcore”. I am not trying to say that Stalinism might happen again – this would be plain silly – but trying to acknowledge emerging authoritarian paradigms, some forms of algorithmic consensual governance techniques developed within neoliberal authoritarianism, heavily relying on conformism, “family” values and positive feedback, and backed up by all-out torture and secret legislation if necessary. On the other hand things are also falling apart into uncontrollable love. One also has to remember that people did really love Stalin. People love algorithmic governance too, if it comes with watching unlimited amounts of Game of Thrones. But anyone slightly interested in digital politics and technology is by now acquiring at least basic skills in disappearance and subterfuge.

Essentially I think it makes sense to compare our moment with the end of the twenties in the Soviet Union, when euphoria about electrification, NEP (New Economic Policy), and montage gives way to bureaucracy, secret directives and paranoia. Today this corresponds to the sheer exhilaration of having a World Wide Web being replaced by the drudgery of corporate apps, waterboarding, and “normcore”. I am not trying to say that Stalinism might happen again – this would be plain silly – but trying to acknowledge emerging authoritarian paradigms, some forms of algorithmic consensual governance techniques developed within neoliberal authoritarianism, heavily relying on conformism, “family” values and positive feedback, and backed up by all-out torture and secret legislation if necessary. On the other hand things are also falling apart into uncontrollable love. One also has to remember that people did really love Stalin. People love algorithmic governance too, if it comes with watching unlimited amounts of Game of Thrones. But anyone slightly interested in digital politics and technology is by now acquiring at least basic skills in disappearance and subterfuge.

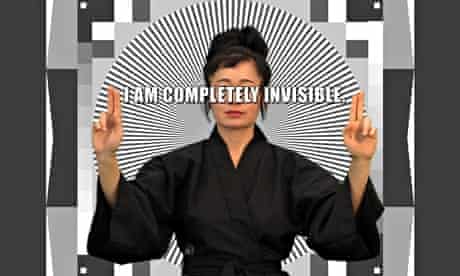

Hito Steyerl, How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013)

MJ In “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy,” you point out that the contemporary art industry “sustains itself on the time and energy of unpaid interns and self-exploiting actors on pretty much every level and in almost every function,” while maintaining that “we have to face up to the fact that there is no automatically available road to resistance and organization for artistic labor.” Bourdieu theorized qualitatively different dynamics in the composition of cultural capital vs. that of economic capital, arguing that the former is constituted by the struggle for distinction, whose value is irreducible to financial compensation. This basically translates to: everyone wants a piece of the art-historical pie, and is willing to go through economic self-humiliation in the process. If striving for distinction is antithetical to solidarity, do you see a possibility of reconciling it with collective political empowerment on behalf of those economically exploited by the contemporary art industry?

HS In Art and Money, William Goetzmann, Luc Renneboog, and Christophe Spaenjers conclude that income inequality correlates to art prices. The bigger the difference between top income and no income, the higher prices are paid for some art works. This means that the art market will benefit not only if less people have more money but also if more people have no money. This also means that increasing the amount of zero incomes is likely, especially under current circumstances, to raise the price of some art works. The poorer many people are (and the richer a few), the better the art market does; the more unpaid interns, the more expensive the art. But the art market itself may be following a similar pattern of inequality, basically creating a divide between the 0,01 percent if not less of artworks that are able to concentrate the bulk of sales and the 99,99 percent rest. There is no short term solution for this feedback loop, except of course not to accept this situation, individually or preferably collectively on all levels of the industry. This also means from the point of view of employers. There is a long term benefit to this, not only to interns and artists but to everyone. Cultural industries, which are too exclusively profit oriented lose their appeal. If you want exciting things to happen you need a bunch of young and inspiring people creating a dynamics by doing risky, messy and confusing things. If they cannot afford to do this, they will do it somewhere else eventually. There needs to be space and resources for experimentation, even failure, otherwise things go stale. If these people move on to more accommodating sectors the art sector will mentally shut down even more and become somewhat North-Korean in its outlook — just like contemporary blockbuster CGI industries. Let me explain: there is a managerial sleekness and awe inspiring military perfection to every pixel in these productions, like in North Korean pixel parades, where thousands of soldiers wave color posters to form ever new pixel patterns. The result is quite something but this something is definitely not inspiring nor exciting. If the art world keeps going down the way of raising art prices via starvation of it’s workers – and there is no reason to believe it will not continue to do this – it will become the Disney version of Kim Jong Un’s pixel parades. 12K starving interns waving pixels for giant CGI renderings of Marina Abramovic! Imagine the price it will fetch!

- dismagazine.com/disillusioned-2/62143/hito-steyerl-politics-of-post-representation/

Be water, my friend, advised action film star Bruce Lee. Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless like water. Becoming like water is the central, surging theme in Hito Steyerl's new HD video projection Liquidity Inc, one of five works the Berlin-based artist is presenting in the ICA's theatre.

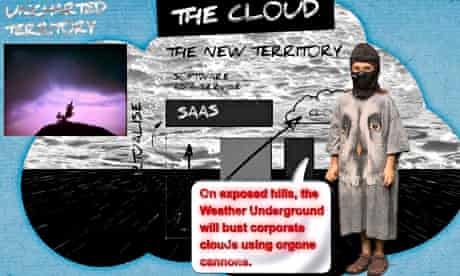

Liquidity Inc tells the story of Jacob Wood, who lost his job when investment bank Lehman Brothers went under in 2008. Wood, born in Vietnam and a war orphan, came to the US under Gerald Ford's Operation Babylift. After investment banking, he turned to the fight game. Images of cage fights and surfers, waves and weather take strange turns in Liquidity Inc's 30 minute duration. The 1990s net-boom and dotcom bubble, the economic weather systems circling the globe and spoof TV weather reports delivered by meteorologists in balaclavas (inspired by the 1970s militant leftwing group the Weather Underground) intersperse the action. The screen surges with electronically enhanced versions of Hokusai's The Great Wave, and Paul Klee's Angelus Novus flaps its wings in a corner of the screen, like an aberrant storm warning. The storm, my friend, is history.

Steyerl's art is extremely rich, dense and rewarding. This befits an artist who trained in Japan, got a PhD in philosophy in Vienna and is a professor of new media art in Berlin. She is also a performer, and two of her "lecture performances" are also in the show, tucked away on monitor screens in the ICA's cavernous theatre, which has become a kind of darkened labyrinth. The staging of her work matters, because what she deals with is itself often about the hidden, the buried, the invisible to the eye.

How Not to Be Seen, a sardonic TV-trained voice-over sneers, announcing the title of what he goes on to call A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File. The sardonic, disembodied voice is familiar from TV adverts and cinema announcements. How Not to Be Seen offers instructions on how to disappear by going off-screen and offline, by hiding in plain sight, cloaking and camouflage. You can also be disappeared by the authorities, eradicated or annihilated.

Paranoia mounts as the announcer runs through the possibilities. You can also become invisible by being poor or undocumented, living in a gated community or in a military zone. Being a woman over 50, owning an "anti-paparazzi handbag" or "being a dead pixel" also work.

Much of the imagery was shot in a militarised area in the California desert, where strange geometric patterns decay on broken tarmac, the remains of resolution targets for drone and spy-plane cameras. The technology has moved on, and these painted signs have been abandoned. In the video, people wear black-and-white boxes on their heads and dance, disappearing into abstract pixelation. A couple twirl in green bodysuits, and a troupe of women in green hijabs dance on the painted tarmac. Ghostly white silhouettes wander manicured hotel gardens and The Three Degrees sing the 1978 hit, When Will I See You Again. Never, perhaps. We've fallen through the digital cracks.

In the museum, no one is safe. Steyerl's 2012 Guards, filmed in the Art Institute of Chicago, focuses on two black museum guards, Ron Hicks and Martin Whitfield. Usually, the guards are invisible to us. Here they stand before us on a tall, vertically oriented video screen and talk, and have a terrific aura of alert self-containment and presence, like well-disciplined cops or marines standing post. These were their previous jobs. Whitfield was a "shit-magnet" cop, always finding himself within a block or two of gang fights and random drive-by shootings. Hicks was in the military. They pace and talk and treat the galleries as their beat, their zones of conflict. The camera follows them as they patrol their rooms, passing the De Koonings and Twomblys, Rothkos and Richters and Eva Hesses. The art's more than incidental backdrop. They're what these guys are here to protect.

Brilliantly shot, staged and choreographed, Guards has tremendous punch, not least because of the air of controlled menace projected by these guards, whom Steyerl has asked to tell their stories. I'll never feel safe in a gallery again. In Is the Museum a Battlefield, one of two recordings of Steyerl's performance lectures, we watch her talk at the 2013 Istanbul Biennial, while outside on the streets the demonstrating populace was being hounded and teargassed by the authorities.

Taking her theme from a visit to an abandoned "minor" battlefield near Van in south-east Turkey, where the artist's militant friend Andrea Wolf, who had joined the PPK, was killed in 1998, Steyerl weaves a long and complicated story about the interconnectedness of war and art museums. She rests on the paradox that the biennial's sponsors and subsiduaries – including Siemens, Lockheed and other corporations – also manufactured military hardware used by the Turkish authorities. Steyerl begins with a shell-casing she found on the battlefield, and sucks in Angelina Jolie, starchitects Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid, Eisenstein's film October, the AK-47 and the rebuilding of the St Petersburg's Hermitage Museum as an outpost of the Guggenheim museum.

The bullet, like a talisman, ricochets through the lecture. Who knows its destination? Everything connects in Steyerl's arguments, which she develops by way of humorous asides, flights of fantasy, and real and imaginary bullets. She's digging the dirt at the heart of the art world. A second lecture, recorded in Berlin last year, presents a mordant picture of the present, through a reading of Victor Hugo's Les Misérables and the gameshow success of Susan Boyle.

With Steyerl, you can't always tell fact from fabulation, where the jokes end and seriousness begins, what is truth and what is a lie. A pleasure in art can unhinge us in everyday life, where we are undone by falsehoods at every turn. At several points in Steyerl's show, I felt out of my depth, deluged by digital rain, swamped by information, caught in the undertow of conspiracy. She makes me want to go offline, become invisible, flow like water and drain away. - Adrian Searle

This exhibition surveys the work of German filmmaker and writer Hito Steyerl, focusing particularly on the artist's production from 2004 onwards. Over this period Steyerl’s films, essays and lectures have uniquely articulated the contemporary status of images, and of image politics. Central to her work is the notion that global communication technologies – and the attendant mediation of the world through circulating images – have had a dramatic impact on conceptions of governmentality, culture, economics and subjectivity itself.

Hito Steyerl presents eight existing works and one new commission within an exhibition design conceived by the artist and her team. The exhibition spans both Artists Space venues and also encompasses a program of talks and screenings, and an online aggregation of Steyerl’s writing.

Steyerl studied documentary filmmaking, and her essay films of the 1990s address issues of migration, multiculturalism and globalization in the aftermath of the formation of the European Union. Her films November (2004) and Lovely Andrea (2007) mark a move towards the extrapolation of the essay form as an open-ended means of speculation. They locate representations of herself and her friend Andrea Wolf as object lessons in the politics played out within the translation and migration of image documents. Steyerl’s prolific filmmaking and writing has since occupied a highly discursive position between the fields of art, philosophy and politics, constituting a deep exploration of late capitalism’s social, cultural and financial imaginaries. Her films and lectures have increasingly addressed the presentational context of art, while her writing has circulated widely through publication in both academic and art journals, often online.

The exhibition begins at Artists Space Exhibitions with Red Alert (2007), an installation that succinctly collapses many of the concerns active in Steyerl’s work. Three vertically-oriented monitors each show the same solid red shade. The monochrome three-screen film provides a humorous “new-media” take on Alexander Rodchenko’s triptych of paintings Pure Colours: Red, Yellow and Blue (1921), an artwork that has been interpreted as both the “end of art” and the “essence of art.” Also referencing the terror alert system introduced by Homeland Security in the wake of 9/11, Red Alert signifies, in Steyerl’s words, “the end of politics as such (end of history, advent of liberal democracy) and at the same time an era of ‘pure feeling’ that is heavily policed.”

These “politics of the monochrome” are carried further into the scenography of the exhibition. The films Guards (2012) and In Free Fall (2010) are located in labyrinthine “black-box” spaces that take the viewer from the claustrophobia of a padded corridor, to first-class airline luxury; whereas Liquidity Inc. (2014) is installed in a space bathed in aquatic blue light. As with the majority of Steyerl’s films, these works extend from research conducted through interviews and the accumulation of found visual material, and move between forensic documentary and dream-like montage. Guards, produced at the Art Institute of Chicago, centers on conversations with museum security staff with previous military or law enforcement careers. Their descriptions of tactics and strategy point to the museum as a site of militarization and privatization, and to their contradictory position between visibility and invisibility within a space of pure affect and sensation. In Free Fall takes as a central motif an aircraft graveyard in the Californian desert, and builds around the biographies of objects and materials held there a web of connections between economic crash, the volatility of the moving-image industry, and the spectacularization of crisis. Steyerl’s most recent film, Liquidity Inc., treats as dual subjects the figure of Jacob Wood, a former investment banker turned MMA fighter, and water, in all its mutable physical and metaphorical states. - artistsspace.org/exhibitions/hito-steyerl

Steyerl studied documentary filmmaking, and her essay films of the 1990s address issues of migration, multiculturalism and globalization in the aftermath of the formation of the European Union. Her films November (2004) and Lovely Andrea (2007) mark a move towards the extrapolation of the essay form as an open-ended means of speculation. They locate representations of herself and her friend Andrea Wolf as object lessons in the politics played out within the translation and migration of image documents. Steyerl’s prolific filmmaking and writing has since occupied a highly discursive position between the fields of art, philosophy and politics, constituting a deep exploration of late capitalism’s social, cultural and financial imaginaries. Her films and lectures have increasingly addressed the presentational context of art, while her writing has circulated widely through publication in both academic and art journals, often online.

The exhibition begins at Artists Space Exhibitions with Red Alert (2007), an installation that succinctly collapses many of the concerns active in Steyerl’s work. Three vertically-oriented monitors each show the same solid red shade. The monochrome three-screen film provides a humorous “new-media” take on Alexander Rodchenko’s triptych of paintings Pure Colours: Red, Yellow and Blue (1921), an artwork that has been interpreted as both the “end of art” and the “essence of art.” Also referencing the terror alert system introduced by Homeland Security in the wake of 9/11, Red Alert signifies, in Steyerl’s words, “the end of politics as such (end of history, advent of liberal democracy) and at the same time an era of ‘pure feeling’ that is heavily policed.”

These “politics of the monochrome” are carried further into the scenography of the exhibition. The films Guards (2012) and In Free Fall (2010) are located in labyrinthine “black-box” spaces that take the viewer from the claustrophobia of a padded corridor, to first-class airline luxury; whereas Liquidity Inc. (2014) is installed in a space bathed in aquatic blue light. As with the majority of Steyerl’s films, these works extend from research conducted through interviews and the accumulation of found visual material, and move between forensic documentary and dream-like montage. Guards, produced at the Art Institute of Chicago, centers on conversations with museum security staff with previous military or law enforcement careers. Their descriptions of tactics and strategy point to the museum as a site of militarization and privatization, and to their contradictory position between visibility and invisibility within a space of pure affect and sensation. In Free Fall takes as a central motif an aircraft graveyard in the Californian desert, and builds around the biographies of objects and materials held there a web of connections between economic crash, the volatility of the moving-image industry, and the spectacularization of crisis. Steyerl’s most recent film, Liquidity Inc., treats as dual subjects the figure of Jacob Wood, a former investment banker turned MMA fighter, and water, in all its mutable physical and metaphorical states. - artistsspace.org/exhibitions/hito-steyerl

Empire of the Senses

Police as art and the crisis of representation

In the Empire of the senses, police becomes an expert in aesthetics. The colors of the terror alert system are just one example of how the police paints moods and atmosphere. A strategy, which has a long tradition in monochrome paintings. But adopting the aesthetic strategies of the monochrome is not confined to terror alerts, but has become a trademark of postpolitical aesthetics.

First appeared in Transversal 09/07: Art and Police, 2007

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

In Defense of the Poor Image

The poor image is no longer about the real thing – the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence; about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation.

First appeared in e-flux journal #10, 2009

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

Politics of the Archive

Translations in Film

The afterlife, as Walter Benjamin once famously mentioned, is the realm of translation. This also applies to the afterlife of films. In this sense, this text deals with translation: with the transformations of two films, whose original prints were caught up in warfare, transformations which include transfer, editing, translation, digital compression, recombination and appropriation.

First appeared in Transversal 06/08: Borders, Nations, Translations, 2008

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Missing People

Entanglement, Superposition, and Exhumation as Sites of Indeterminacy

The zone of zero probability, the space in which image/objects are blurred, pixelated, and unavailable, is not a metaphysical condition. It is in many cases man-made, and maintained by epistemic and military violence, by the fog of war, by political twilight, by class privilege, nationalism, media monopolies, and persistent indifference.

First appeared in e-flux journal #38, 2012.

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

Truth Unmade

Productivism and factography

Perhaps documentary truth thus cannot be produced, just as community cannot be produced. If it were produced, it would belong to the world of the factum verum or the paradigm of instrumentality and governmentality, which traditionally imposes itself on documentary truth production (and which I have elsewhere called documentality). But this other mode of documentary emerges at a point, where documentality, as well as the instrumentality, pragmatism and utility that go along with it, are ruptured.

First appeared in Transversal 09/10: New Productivisms, 2010

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Documentarism as Politics of Truth

Documentality describes the permeation of a specific documentary politics of truth with superordinated political, social and epistemological formations. Documentality is the pivotal point, where forms of documentary truth production turn into government – or vice versa.

First appeared in Transversal 10/03: Differences & Representations, 2003

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

The Language of Things

A documentary image obviously translates the language of things into the language of humans. On the one hand it is closely anchored within the realm of material reality. But it also participates in the language of humans, and especially the language of judgement, which objectifies the thing in question, fixes its meaning and constructs stable categories of knowledge to understand it. It is half visual, half vocal, it is at once receptive and productive, inquisitive and explanatory, it participates in the exchange of things but also freezes relations between them within visual and conceptual still images.

First appeared in Transversal 06/06: Under Translation, 2006

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

In Free Fall

A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective

The view from above is a perfect metonymy for a more general verticalization of class relations in the context of an intensified class war from above – seen through the lenses and on the screens of military, entertainment, and information industries. It is a proxy perspective that projects delusions of stability, safety, and extreme master onto a backdrop of expanded 3D sovereignty.

First appeared in e-flux journal #24, 2011

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

Download PDF

A Thing Like You and Me

There might still be an internal and inaccessible trauma that constitutes subjectivity. But trauma is also the contemporary opium of the masses – an apparently private property that simultaneously invites and resists foreclosure. And the economy of this trauma constitutes the remnant of the independent subject. But then if we are to acknowledge that subjectivity is no longer a privileged site for emancipation, we might as well just face it and get on with it.

First appeared in e-flux journal #15, 2010

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

The Institution of Critique

The criticism of authority is according to Kant futile and private. Freedom consists in accepting that authority should not be questioned. Thus, this form of criticism produces a very ambivalent and governable subject, it is in fact a tool of governance just as much as it is the tool of resistance as which it is often understood. But the bourgeois subjectivity which was thus created was very efficient. And in a certain sense, institutional criticism is integrated into that subjectivity, something which Marx and Engels explicitly refer to in their Communist manifesto, namely as the capacity of the bourgeoisie to abolish and to melt down outdated institutions, everything useless and petrified, as long as the general form of authority itself isn't threatened.

First appeared in Transversal 01/06: Do You Remember Institutional Critique?, 2006.

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Is a Museum a Factory?

Today, cinematic politics are post-representational. They do not educate the crowd, but produce it. They articulate the crowd in space and time. They submerge it in partial invisibility and then orchestrate their dispersion, movement, and reconfiguration. They organize the crowd without preaching to it. They replace the gaze of the bourgeois sovereign spectator of the white cube with the incomplete, obscured, fractured, and overwhelmed vision of the spectator-as-laborer.

First appeared in e-flux journal #7, 2009

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

Politics of Art

Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-Democracy

Even though political art manages to represent so-called local situations from all over the globe, and routinely packages injustice and destitution, the conditions of its own production and display remain pretty much unexplored. One could even say that the politics of art are the blind spot of much contemporary political art.

First appeared in e-flux journal #21, 2010

Published by e-flux

Published by e-flux

Culture and Crime

In the global North, this sphere of privacy offers a whole range of different life styles. They suggest the complete freedom to design one's own living conditions - provided that they remain private and remain restricted to the recognition of individually culturalized identities. Difference is tolerated within the system of cultural domestication - but not as opposition to the system itself. Opposition is thus replaced by cultural difference.

First appeared in Transversal 01/01: Cultura Migrans, 2001

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

The Articulation of Protest

Which movement of political montage then results in oppositional articulation - instead of a mere addition of elements for the sake of reproducing the status quo? Or to phrase differently: Which montage between two images/elements could be imagined, that would result in something different between and outside these two, which would not represent a compromise, but would instead belong to a different order - roughly the way someone might tenaciously pound two stones together to create a spark in the darkness?

First appeared in Transversal 03/03: Mundial, 2003

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

Published by eipcp – European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

The exhibition continues at Artists Space Books & Talks, with November and Lovely Andrea shown consecutively in the basement space. Steyerl’s teenage friend Andrea Wolf, who became a martyr of the Kurdish liberation movement when killed in Çatak, Turkey in 1998, serves as a driving force underlying both works. Steyerl develops a reflexive investigative approach in these two films, in which she documents her journeys in tracing the circulation of particular images and strands of information. This approach positions her own body and subjectivity, alongside that of Wolf, between primary documents and allegorical sites – at which complex flows of desire, control and capital intersect.

Such an approach is also evident in documentation of three lectures exhibited on the ground floor. In recent years Steyerl’s practices as filmmaker and writer have intersected in these events, which begin as public lectures given by the artist and then find a second form in their documentation and presentation both online and in exhibitions. They are distinctive in placing Steyerl center stage – as investigative voice, as image “body,” as subject and object – and catalyze theoretical speculation with their use of visual and linguistic cues. I Dreamed a Dream (2013), Is the Museum a Battlefield? (2013) and Duty-Free Art (2015) depart from experiences the artist recounts, that blur the lines between fact and fiction. Particularly present in these lectures are Steyerl’s visits to Kurdistan and to the site of Andrea Wolf’s murder, which have brought Steyerl in contact with the current humanitarian crisis in the region, stemming from military actions in Syria.

Duty-Free Art is a new lecture, presented for the first time at the opening of this exhibition. It builds a thread of connections between leaked emails from Syrian government accounts, and the growing phenomenon of the “freeport” – storage facilities where millions of dollars of artworks are held without incurring taxes. As concentrated sites of the dialectics apparent in Steyerl’s films and writing, her lectures articulate the notion of the artist as performing image, as producer and as circulator. Steyerl has coined the term “circulationism” in order to describe a state that is “not about the art of making an image, but about post-producing, launching, and accelerating it.”

This exhibition is supported by the Friends of Artists Space; the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts; and the Hito Steyerl Exhibition Supporters Circle: Andrew Kreps Gallery, Eleanor Cayre, Nion McEvoy, and the Goethe-Institut New York.

With thanks to David Riff for the co-design of the exhibition, Christoph Manz for technical direction, Wilfried Lentz, Andrew Kreps, Alice Conconi, and Micha Amstad.

With thanks to David Riff for the co-design of the exhibition, Christoph Manz for technical direction, Wilfried Lentz, Andrew Kreps, Alice Conconi, and Micha Amstad.

Download PDF

The key theorist/practitioner of the post-Internet moment – her dispatches on e-flux journal required reading, her essayistic video artworks required viewing – is too shrewd to get caught up in its impending immolation. This year, with her complex and effervescent film Factory of the Sun (set in a Tron-style motion-capture viewing environment), in which humans melt into light-driven virtuality, Steyerl made one of the few successful national presentations at the Venice Biennale (and one of the only ones that felt future-facing). At the core of Steyerl’s work –alongside investigations of the relationship between art, money, politics and militarisation – is the question of how one retains subjectivity and autonomy in our surveillance-rife, digitally enhanced era. Currently, her first solo show in her native Germany, in Berlin (where she’s a professor at the University of the Arts), featuring Liquidity Inc (2014), is prefaced with a quote from Bruce Lee: ‘Be water, my friend!’ Artist, writer, lecturer and full-on classification escapologist, Steyerl practises what the kung-fu master preaches. - artreview.com/power_100/hito_steyerl/

The key theorist/practitioner of the post-Internet moment – her dispatches on e-flux journal required reading, her essayistic video artworks required viewing – is too shrewd to get caught up in its impending immolation. This year, with her complex and effervescent film Factory of the Sun (set in a Tron-style motion-capture viewing environment), in which humans melt into light-driven virtuality, Steyerl made one of the few successful national presentations at the Venice Biennale (and one of the only ones that felt future-facing). At the core of Steyerl’s work –alongside investigations of the relationship between art, money, politics and militarisation – is the question of how one retains subjectivity and autonomy in our surveillance-rife, digitally enhanced era. Currently, her first solo show in her native Germany, in Berlin (where she’s a professor at the University of the Arts), featuring Liquidity Inc (2014), is prefaced with a quote from Bruce Lee: ‘Be water, my friend!’ Artist, writer, lecturer and full-on classification escapologist, Steyerl practises what the kung-fu master preaches. - artreview.com/power_100/hito_steyerl/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar