Uradi-sam, lo-fi, kolažna umjetnost - u filmu, slikarstvu, skulpturi, poeziji - još od ranih '60-ih. Nijeme, monokromne krimi-drame, ludi znanstvenik Dr. Gaz i Vulvana u crnoj rupi pop-kulture...

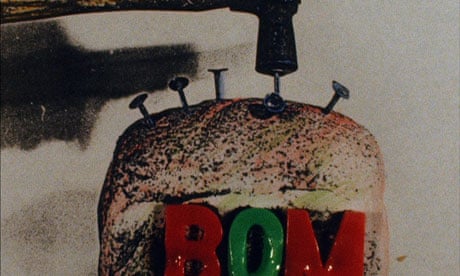

The fiercely original film-maker, poet and artist Jeff Keen, who has died aged 88, defied categorisation. He produced a vast body of paintings, drawings, sculpture and punchy Beat poetry, but is best known for his films, which incorporated collage, animation, found footage and live action – often all in one work. Keen used highly innovative techniques of superimposition and editing, and frequently etched and degraded the film surface. Works such as Marvo Movie (1967), Rayday Film (1968-75) and Mad Love (1972-78) were shot with his friends and family either at home, on the streets of Brighton or at the local tip; their fantastical, DIY countercultural qualities evoked the spirit of Andy Warhol's Factory and the early cinema pioneers of Brighton, where Keen lived. Despite making his first film in his late 30s, he completed more than 70 films and videos throughout his life.

Keen was born in Trowbridge, Wiltshire, and had a love of wildlife, art and books as a child. He attended grammar school and gained an Oxford scholarship, but this was thwarted by his national service in 1942. Keen was given experimental tanks and aeroplane engines to trial during the war, and would frequently refer back to this period in films such as Meatdaze (1968), which included bombers and sirens on its soundtrack, and Artwar (1993).

After the war, Keen developed a love of movies and comics and attended a small art college in Chelsea. London life encouraged his love of the arts, especially surrealism, Picasso and Dubuffet. When he moved to Brighton, Keen took up work as a landscape gardener for the local council. In 1956, he married Jackie Foulds, who was the muse for his films in the 1960s and 70s, playing the characters Vulvana, The Catwoman and Nadine. Keen himself had a B-movie-style "mad scientist" alter ego named Dr Gaz.

One of his early films, The Autumn Feast (1961), was made with the poet Piero Heliczer, who was part of the Warhol set. From the early 1960s, Keen experimented with "expanded cinema" (film events that exceed the normal modes of cinema projection), combining multiple projections and live art performance. A regular contributor to the "happenings" scene of 1960s London, at the Better Books shop in Charing Cross Road and elsewhere, he also participated in the International Underground Film festival at the National Film Theatre in 1970 and continued to make expansive, surrealist-informed 16mm epics such as White Dust (1970-72) and The Cartoon Theatre of Dr Gaz (1976-79), as well as 8mm diary films. He painted throughout the 60s and 70s and made artist books inspired by his films.

Keen's interest in myth, surrealism and romantic painting complemented his love of movies and comics, and he continually absorbed new references into his work. His highly frenetic videos of the 1990s included homages to Apocalypse Now, Rambo and Predator as well as Budd Boetticher westerns. Although his work has always been featured in historical surveys of British experimental and avant-garde cinema, these qualities distinguished his films from more purely formalist works made at the London Filmmakers' Co-Operative, an organisation he helped to found in 1966. It meant his work was often more appreciated by skaters and punks than followers of the canonical avant garde. The extreme, short edits in his playful, visceral films have helped to keep his work fresh and alive; they still zap with energy decades later.

When able, Keen made drawings virtually every day for the last 20 years of his life. His art, which ranges from beautifully worked paintings to surrealist assemblages, collages and free-form drawings, has been rarely shown, but recent exhibitions in Paris and New York initiated by Stella have resulted in new critical acclaim. A Keen installation and related events will be presented at Tate Modern's new Tanks exhibition space in September 2012.

I worked with Keen throughout 2008 on a series of restorations, a film season and a BFI DVD boxset, GAZWRX: The Films of Jeff Keen. The process was undertaken at great speed, much like the pace of his films. We discussed everything from B-movies to Wagner to William Blake. I followed his instructions diligently along the way, but discovered that in speeding up some electronic drawings made on a children's toy, and turning them into a two-channel video, we had made a new piece of work, Omozap Terribelis + Afterblatz 2. He grew excited and wanted to make more new things, despite his declining health. It was typical of what had been his persistent desire, even need, to make art. As he said in the early 1960s: "If words fail, use your teeth. If teeth fail, draw in the sand." Whatever it takes, art must happen. - William Fowler

Jeff Keen was a hugely prolific experimental artist who moved easily between painting, poetry, sculpture and cinema, often with collage as his basic approach. His lo-fi, DIY aesthetic, fascination with popular culture, sexual openness, the way he roped in friends and relatives, and his playful approach to personae echoed Warhol's Factory and the trash cinema of the Kuchars and Jack Smith.

Jeff Keen (1923 – 2012)

Jeff Keen was primarily known as a legendary underground filmmaker whose work and activities coincided with the emergence of expanded cinema. He was one of the original participants in the 1960s at the London Filmmakers Co‐op. The BFI and later the British Arts Council supported and enabled Keen to make films and to devise a multitude of drawings and paintings. During this period, Keen maintained jobs as a landscaper in the Parks and Recreation department of his hometown, Brighton, and sometimes as a postal worker delivering mail. The artist made movies primarily on weekends with his family and friends in an ensemble cast and his painting and drawing studio was for 40 years a repository of props and art that accumulated to extraordinary effect.

Keen was able to merge Surrealist and Dadaist ideology with a social‐political critique of American consumerism with the spontaneity of the Beat and 60s era. These works are dynamic responses to an overwhelming sense of increasingly proliferating media and commodification during the decade. He often explored his experiences surviving World War II in this material, focusing on monuments of power and the ever‐present war within the artist as individual. Keen made use of invented characters or corporations (ie. RaydayFilms) with brands, personas or protagonists in a fractured, narrative style. Performative and reminiscent of Surrealism’s influence on his seminal period in the 1950s, Keen additionally drew from English Romanticism and his love of language to devise a novel method of working in a newly evolving medium.

Keen’s work can be viewed today as prescient to modes of film and video that began to take cultural references into an exploration of our own larger social portraiture. His enthusiastic embrace of alternative modes of discourse in a pre‐Internet age is astoundingly fresh today, and the diversity of his practice calls to mind both painters, film and video artists who succeeded him, from such figures as Derek Jarman, Richard Hamilton and Linder, to American artists such as Jack Smith, Ryan Trecartin and Peter Saul.

Jeff Keen very rarely exhibited his drawings and paintings. His first United States solo exhibition, Jeff Keen:Works from the 1960s + 1970s was held January 18 – February 18 this year at Elizabeth Dee, New York and included drawings, paintings and films. In tandem, the gallery initiated an offsite collaboration with Broadway 1602, New York. Upcoming 2012 exhibitions and screenings include: Brighton and Hove Museum (retrospective), the National Portrait Gallery, London (solo) and Tate Modern, London (group). - now.elizabethdee.com

Jeff Keen began making films in 1960 at the age of 37 and very quickly settled on certain references and techniques. Shot on 8mm, the beatnik-style shorts Wail (1960) and Like The Time Is Now (1961) are at once both home movies of friends at play and astonishing revelations of what can be done with imagination, limited means and a tiny film frame. On seeing these films, critic and Keen fan Raymond Durgnat later wrote: "He cuts, not with scissors but a scalpel - a jet propelled one!" In Wail, images of brutal gang violence collide with war paintings and a horror-movie werewolf. His films use animation, B-movie references, noise soundtracks and costumed character play to articulate sublime, intuitive experience and to subvert and explore the dynamic links between different areas of culture - William Fowler, Sight & Sound (Mar 09).

These are Jeff Keen's standard 8mm films (disc three in the BFI set). The DVD groups them as follows...

Early 8mm Films:

Wail - 1960, 4m32s, black & white, silent, 4:3.

Like The Time Is Now - 1961, 5m31s, black & white, silent, 4:3.

Breakout - 1962, 11m19s, black & white, silent, 4:3.

Instant Cinema - 1m26s, colour, sound, 4:3.

Flik Flak - 1964-5, 3m23s, colour, sound, 4:3.

The Pink Auto - 1964-5, 20m56s, colour, sound, 16:9.

Missing Close-Ups - 1964-5, 4m24s, colour, silent, 4:3.

Day of the Arcane Light - 1969, 13m37s, colour, sound, 4:3.

Family Star:

Mutt & Jeff Icecream Sundae and Mothman - 1968-9, 31m29s, colour, sound, 16:9.

Self Portrait:

Spontaneous Combustion - 33m34s, colour, silent, 16:9.

Extras:

Interview with Jeff Keen (24m35s)

Art Flies Free (2m59s)

Jeff Keen has been collecting props from dumpsters and toy shops, spray painting them, setting fire to them and animating the results for forty years. His underground films pre-date Warhol, his fans include some of the most notorious and legendary figures in the world of cinema - Jack Sargeant, sleazenation 2004.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar