Meandrirajući između književnosti, filozofije, matematike i znanosti Frampton je uobličio svoj osnovni interes - izražavanje sekvencijalnih mogućnosti fotografije i filma. Znanstvene apstrakcije, strukturalni principi, logika umjetnosti - slastice za ljubitelje visokointelektualne umjetnosti.

Hollis Frampton (1936-1984) na UbuWebu:

Heterodyne (1967)

Heterodyne (1967)

Snowblind (1968)

Snowblind (1968)

Artificial Light (1969)

Artificial Light (1969)

Paindrome (1969)

Paindrome (1969)

Ordinary Matter (1972)

Ordinary Matter (1972)

Autumnal Equinox (1974)

Autumnal Equinox (1974)

Noctiluca (Magellan's Toys: #1) (1974)

Noctiluca (Magellan's Toys: #1) (1974)

Matrix [First Dream] (1977-79)

Matrix [First Dream] (1977-79)

Conversations in the Arts.

Interview with Hollis Frampton, Ester Harriott (1978)

Conversations in the Arts.

Interview with Hollis Frampton, Ester Harriott (1978)

Hollis Frampton on Hollis Frampton:

"Hollis Frampton was born in Ohio, United States, on March 11, 1936,

towards the end of the Machine Age. Educated (that is, programmed:

taught table manners, the use of the semicolon, and so forth) in Ohio

and Massachusetts. The process resulted in satisfaction for no one.

Studied (sat around on the lawn at St. Elizabeths) with Ezra Pound,

1957-58. That study is far from concluded. Moved to New York in March,

1958, lived and worked there more than a decade. People I met there

composed the faculty of a phantasmal 'graduate school'. Began to make

still photographs at the end of 1958. Nothing much came of it. First

fumblings with cinema began in the Fall of 1962; the first films I will

publicly admit to making came in early 1966. Worked, for years, as a

film laboratory technician. More recently, Hunter College and the Cooper

Union have been hospitable. Moved to Eaton, New York in mid-1970, where

I now live (a process enriched and presumably, prolonged, by the

location) and work...

In the case of painting, I believe that one reason I stayed with still

photography as long as I did was an attempt, fairly successful I think,

to rid myself of the succubus of painting. Painting has for a long time

been sitting on the back of everyone's neck like a crept into

territories outside its own proper domain. I have seen, in the last year

or so, films which I have come to realize are built largely around what

I take to be painterly concerns and I feel that those films are very

foreign to my feeling and my purpose. As for sculpture, I think a lot of

my early convictions about sculpture, in a concrete sense, have

affected my handling of film as a physical material. My experience of

sculpture has had a lot to do with my relative willingness to take up

film in hand as a physical material and work with it. Without it, I

might have been tempted to more literary ways of using film, or more

abstract ways of using film."

RELATED RESOURCES:

Hollis Frampton in UbuWeb Sound

Hollis Frampton in UbuWeb Sound

Hollis Frampton: Words & Pictures

Matt Packer

An extended review of 'On the Camera Arts & Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton' (1).

On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton

is the most extensive collection of writings by the photographer and

filmmaker to date. Frampton's previous collection of writings, Circles of Confusion,

was published over 25 years ago and is now long out of print.

Fortunately, those same texts are contained within this new book, which

also features a wide variety of additional texts that reflect the

breadth of Frampton's inquiries. These inquiries fall into sections on

Photography, Film, Video and the Digital Arts, The Other Arts, and Texts

- including previously unpublished writings, notes on Frampton's own

work, as well as critical articles written for the pages of magazines

such as Artforum and various long- since forgotten film journals. Among

other insightful inclusions are narrations and scripts for films such as

(nostalgia) and Zorn's Lemma, typescripts of

hand-written letters, and a curious funding application to the National

Endowment for the Arts for the development of computer software of

Frampton's own design.

The book's breadth is testimony to the myriad ways in which writing had a place in Frampton's life and work; existing in the private and reflexive spaces of his practice, as well as in the public channels of art criticism and commentary.

In a recorded interview with Ester Harriott in 1978, Frampton spoke of writing as a ‘slow, unforgiving process... a kind of dread obligation'. Even this short quotation gives a suggestion to Frampton's commitments as a writer, both to the laboured precision of his language, and to the feeling of responsibility (obligation) in sustaining the discourses about art, and film most particularly. In that same interview with Harriott, Frampton identified his efforts as a writer as part of the ‘noble tradition' of other luminary filmmaker-writers such as Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein; each in their own generation setting forth the discursive territory that was both prescient and contributory to their own practice as filmmakers. As Bruce Jenkins writes in his introductory text: ‘The impetus for Hollis Frampton's writing stemmed in part from what he deemed the paucity and poverty of then-contemporary critical discourse on the camera arts'.

Arriving upon the New York art scene in late 1950s, Frampton's frustration with the photographic and filmic discourses he then encountered were perhaps stoked by his exposure to the rigour of other arts' discourses, especially those taking place in the expanded field of sculpture with the emergence of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Indeed, it was the sculptor Carl Andre that became one of Frampton's most recurrent - if itinerant - conversation partners; culminating in a series of typed dialogues between the two artists, published by the New York University Press as 12 Dialogues 1962-1963. Frampton's preface to 12 Dialogues is reprinted here, along with one of the more expansive examples of his collaboration with Andre - On Plasticity and Consecutive Matters. These dialogues give evidence of Frampton's familiarity and confidence in discussing other art forms beyond his own practice, and a broad range of topics besides. Frampton's dialogues with Andre are also exemplary of their shared interest in putting the capabilities of language to the full test of art's empirical and material existences; a test of language that was entrusted in their friendship and probably helped along with one abusive substance or another.

Carl Andre: ...I was caught by the thought that the poor crystals could extend themselves only by accretion. Not a single fuck in a pound of chrome alum. Even the slippery paramecium enjoys the pleasures of conjugation...

Hollis Frampton: ...Crystalline structure is a habit of matter arrested at the level of logic. Logic is an invention for winning arguments, and matter wins its argument with ionic dissolution by crystallizing. A logical argument cannot change; it can only extend itself into a set of tautological consequences...

In taking the above excerpt out of context, it might be impossible to deduce that Andre and Frampton were corresponding on the paintings of Frank Stella. This is however, a fairly typical example of their dialogical adventures: relating scientific abstractions and structural principles to the logic of art. It is important to consider that their use of scientific and academic vocabulary was not necessarily a strategic attempt to export art's value into other disciplines. Instead, theirs was a libratory exercise: ransacking other disciplinary vocabularies for words and phrasings that defied the stringencies of existing art discourse, while also appealing to their particular shared interests in sequence, structure, and materiality of the constructed world. The libratory aspect of Andre and Frampton's dialogue is further suggested in Frampton's text for the preface of 12 Dialogues, in which he urged that they be read ‘as anthropological evidence pertaining to a rite of passage and to the nature of friendship'.

Critically incisive or a play-upon-form: the language that Frampton employed in his writings was alternately one thing and another, and often had the strength to be both. In this sense, it confers what Melissa Gronlund has recently described of Frampton's writings as existing 'between stentorian intellect and impish game-playing' that became a hallmark of his filmmaking. The editorial approach of On the Camera Arts is appropriately generous in allowing the critical and playful aspects of Frampton's output as a writer to co-exist and intercede, without being bound to false binaries or expedient contradictions that would misrepresent his broader practice. However, it's a similar reckoning that disqualifies On the Camera Arts from being an accessible, first-port-of-call for anyone not already familiar with Frampton's work.

There are texts which are close to being essayist, such as Eadweard Muybridge: Fragments of a Tesseract, that jump deftly between philosophical and literary reference, history, and biography of the 19th century photographer, through to the more oblique A Pentagram for Conjuring the Narrative: a study of narrative structure in the explication of a dream sequence, the authorial matrix of Samuel Beckett, and various algebraic equations of literary biography.

Joseph Conrad insisted that any man's biography could be reduced to a series of three terms: "He was born. He suffered. He died." It is the middle term that interests us here. Let us call it "x". Here are four different expansions of that term, or true accounts of the suffering of x, by as many storytellers.

Ultimately, Frampton's meanderings through the realms of literature, philosophy, mathematics, and science, were tools in his intellectual toolbox - called into being as a way of shaping his primary expression in the sequential possibilities of photography and film. As the example above demonstrates, Frampton's dexterity as a writer and thinker was, at times, suspiciously close to intellectual wayfaring. At worst, reading Frampton can feel like following a tour guide that equally basks in the glory of being so far from home.

While Frampton's writings often made testing demands upon the reader, it is important to consider these texts in the same ‘rite of passage' spirit that Frampton himself acknowledged in 12 Dialogues. Such a rite of passage might translate as a call upon readers to forgo all referential twists and turns as a process of working-through Frampton's scheme of ideas. There would be a similar call to viewers in films such as Zorn's Lemma or Gloria!

Before turning to the relationships of text and language in Frampton's film work, which undoubtedly provides On the Camera Arts its primary basis of contribution and insight, some consideration should be given to Frampton's previous occupations with poetry and still photography.

Frampton's poetry is referred to frequently in interviews, but neither does it appear in the pages of On the Camera Arts or is it ever discussed in detail. Frampton himself is quick to dismiss and downplay his contribution to the field: previously calling his own efforts as a poet "a disaster". Nevertheless, poetry makes a definite entry in the retrospection of Frampton's interests in language, starting with his acquaintance with Ezra Pound when Frampton was aged 21.

It was through still photography that Frampton found recognition, exhibiting his work and also writing texts on established figures in early-mid twentieth century modernist photography such as Edward Weston and Paul Strand, many of which appear in the book. Frampton's recognition that his own photography tended toward serialisation and time-regulated sequence caused him to seek a move into film.

If we allow Frampton's background in poetry and still photography to represent the alternations of language and image, then it was film that allowed these alternations to be compounded most effectively.

Zorn's Lemma (1970) is such a film. Consisting of three sections, the film begins with a blank screen. A woman's voice is heard, speaking a list of learning-rhymes from an antiquated grammar textbook for children. These are spoken alphabetically, according to noun:

Thy Life to mend,

God's Book attend.

The Cat doth play,

And after slay.

What follows these readings is an animated series of word-images in the form of photographs of street-signage or ‘found' texts, mostly collected from Frampton's wanderings in New York; "a phantasmagoria of environmental language" as Scott MacDonald has referred to it. After a while, we begin to recognise the alphabetical pattern in the sequencing of these word-image photographs. The photographs present signs for ‘Needle', ‘Office', ‘Pal', for example; appearing in alphabetical order. The pattern recognition of the sequence has the effect of pulling the expectancy of the next, so that each subsequent image-text photograph builds to a kind of alphabetical mantra.

The stability of this textual pattern begins to disintegrate through the gradual substitution of image-texts for images of a different kind. Where we might expect to read the ‘B' in street signs for Barber, Bar, or Bonanza, we're presented with a short film sequence of a frying egg. Further substitutions occur: ‘O' becomes a bouncing ball; ‘X' becomes fire; ‘L' becomes a child swinging, until the pattern losses its sense of textual coordination entirely. In this way, a film such as Zorn's Lemma can be understood as a test of reciprocity in the exchange of language and images; ultimately, a zero sum game that reveals nothing other than the structure of their interdependency.

Another film that gives example of Frampton's compounding of literary and photographic narratives is (nostalgia), produced in 1971 with the assistance of friend and fellow filmmaker Michael Snow, who provides the voiceover for the film. Featuring a sequence of black and white photographs taken by Frampton, placed upon a ring-burner until they shrivel and burn, (nostalgia) corresponds directly to Frampton's previous incarnation as a still photographer. Furthermore, a voiceover recalls stories and anecdotes that relate to the photographs, in the context of Frampton's experiences in New York City (scripted by Frampton, spoken by Snow).

It soon becomes obvious that the photograph that the voiceover describes is not the photograph presented, but the description of the image to follow. Not only does this cause a temporal disconnection between language and image, but the viewer comes to rely on expectations of the next image by way of a description that precedes it; meanwhile the present image burns. As Rachel Moore has written in her book dedicated to the film, "the burnt photograph spent by language that quivers in front of us, registers this fall precipitated by language."

Both Zorn's Lemma and (nostalgia) give example of how language was central to Frampton's filmmaking; not as a mere aspect, but as an integral and forming structure woven into the capabilities of photographic images and film. It is this that also provides the challenge to a book like On the Camera Arts, which may have otherwise taken the opportunity to establish an easy inroad to Frampton's work upon the 25th year anniversary of his death. Despite such warnings, the book succeeds in appropriately sustaining the torsion of Frampton's inquiries, while contributing greatly to contemporary and retrospective discourses on the development of film in the interceptive spaces of art.

The book's breadth is testimony to the myriad ways in which writing had a place in Frampton's life and work; existing in the private and reflexive spaces of his practice, as well as in the public channels of art criticism and commentary.

In a recorded interview with Ester Harriott in 1978, Frampton spoke of writing as a ‘slow, unforgiving process... a kind of dread obligation'. Even this short quotation gives a suggestion to Frampton's commitments as a writer, both to the laboured precision of his language, and to the feeling of responsibility (obligation) in sustaining the discourses about art, and film most particularly. In that same interview with Harriott, Frampton identified his efforts as a writer as part of the ‘noble tradition' of other luminary filmmaker-writers such as Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein; each in their own generation setting forth the discursive territory that was both prescient and contributory to their own practice as filmmakers. As Bruce Jenkins writes in his introductory text: ‘The impetus for Hollis Frampton's writing stemmed in part from what he deemed the paucity and poverty of then-contemporary critical discourse on the camera arts'.

Arriving upon the New York art scene in late 1950s, Frampton's frustration with the photographic and filmic discourses he then encountered were perhaps stoked by his exposure to the rigour of other arts' discourses, especially those taking place in the expanded field of sculpture with the emergence of Minimalism and Conceptual Art. Indeed, it was the sculptor Carl Andre that became one of Frampton's most recurrent - if itinerant - conversation partners; culminating in a series of typed dialogues between the two artists, published by the New York University Press as 12 Dialogues 1962-1963. Frampton's preface to 12 Dialogues is reprinted here, along with one of the more expansive examples of his collaboration with Andre - On Plasticity and Consecutive Matters. These dialogues give evidence of Frampton's familiarity and confidence in discussing other art forms beyond his own practice, and a broad range of topics besides. Frampton's dialogues with Andre are also exemplary of their shared interest in putting the capabilities of language to the full test of art's empirical and material existences; a test of language that was entrusted in their friendship and probably helped along with one abusive substance or another.

Carl Andre: ...I was caught by the thought that the poor crystals could extend themselves only by accretion. Not a single fuck in a pound of chrome alum. Even the slippery paramecium enjoys the pleasures of conjugation...

Hollis Frampton: ...Crystalline structure is a habit of matter arrested at the level of logic. Logic is an invention for winning arguments, and matter wins its argument with ionic dissolution by crystallizing. A logical argument cannot change; it can only extend itself into a set of tautological consequences...

In taking the above excerpt out of context, it might be impossible to deduce that Andre and Frampton were corresponding on the paintings of Frank Stella. This is however, a fairly typical example of their dialogical adventures: relating scientific abstractions and structural principles to the logic of art. It is important to consider that their use of scientific and academic vocabulary was not necessarily a strategic attempt to export art's value into other disciplines. Instead, theirs was a libratory exercise: ransacking other disciplinary vocabularies for words and phrasings that defied the stringencies of existing art discourse, while also appealing to their particular shared interests in sequence, structure, and materiality of the constructed world. The libratory aspect of Andre and Frampton's dialogue is further suggested in Frampton's text for the preface of 12 Dialogues, in which he urged that they be read ‘as anthropological evidence pertaining to a rite of passage and to the nature of friendship'.

Critically incisive or a play-upon-form: the language that Frampton employed in his writings was alternately one thing and another, and often had the strength to be both. In this sense, it confers what Melissa Gronlund has recently described of Frampton's writings as existing 'between stentorian intellect and impish game-playing' that became a hallmark of his filmmaking. The editorial approach of On the Camera Arts is appropriately generous in allowing the critical and playful aspects of Frampton's output as a writer to co-exist and intercede, without being bound to false binaries or expedient contradictions that would misrepresent his broader practice. However, it's a similar reckoning that disqualifies On the Camera Arts from being an accessible, first-port-of-call for anyone not already familiar with Frampton's work.

There are texts which are close to being essayist, such as Eadweard Muybridge: Fragments of a Tesseract, that jump deftly between philosophical and literary reference, history, and biography of the 19th century photographer, through to the more oblique A Pentagram for Conjuring the Narrative: a study of narrative structure in the explication of a dream sequence, the authorial matrix of Samuel Beckett, and various algebraic equations of literary biography.

Joseph Conrad insisted that any man's biography could be reduced to a series of three terms: "He was born. He suffered. He died." It is the middle term that interests us here. Let us call it "x". Here are four different expansions of that term, or true accounts of the suffering of x, by as many storytellers.

Ultimately, Frampton's meanderings through the realms of literature, philosophy, mathematics, and science, were tools in his intellectual toolbox - called into being as a way of shaping his primary expression in the sequential possibilities of photography and film. As the example above demonstrates, Frampton's dexterity as a writer and thinker was, at times, suspiciously close to intellectual wayfaring. At worst, reading Frampton can feel like following a tour guide that equally basks in the glory of being so far from home.

While Frampton's writings often made testing demands upon the reader, it is important to consider these texts in the same ‘rite of passage' spirit that Frampton himself acknowledged in 12 Dialogues. Such a rite of passage might translate as a call upon readers to forgo all referential twists and turns as a process of working-through Frampton's scheme of ideas. There would be a similar call to viewers in films such as Zorn's Lemma or Gloria!

Before turning to the relationships of text and language in Frampton's film work, which undoubtedly provides On the Camera Arts its primary basis of contribution and insight, some consideration should be given to Frampton's previous occupations with poetry and still photography.

Frampton's poetry is referred to frequently in interviews, but neither does it appear in the pages of On the Camera Arts or is it ever discussed in detail. Frampton himself is quick to dismiss and downplay his contribution to the field: previously calling his own efforts as a poet "a disaster". Nevertheless, poetry makes a definite entry in the retrospection of Frampton's interests in language, starting with his acquaintance with Ezra Pound when Frampton was aged 21.

It was through still photography that Frampton found recognition, exhibiting his work and also writing texts on established figures in early-mid twentieth century modernist photography such as Edward Weston and Paul Strand, many of which appear in the book. Frampton's recognition that his own photography tended toward serialisation and time-regulated sequence caused him to seek a move into film.

If we allow Frampton's background in poetry and still photography to represent the alternations of language and image, then it was film that allowed these alternations to be compounded most effectively.

Zorn's Lemma (1970) is such a film. Consisting of three sections, the film begins with a blank screen. A woman's voice is heard, speaking a list of learning-rhymes from an antiquated grammar textbook for children. These are spoken alphabetically, according to noun:

Thy Life to mend,

God's Book attend.

The Cat doth play,

And after slay.

What follows these readings is an animated series of word-images in the form of photographs of street-signage or ‘found' texts, mostly collected from Frampton's wanderings in New York; "a phantasmagoria of environmental language" as Scott MacDonald has referred to it. After a while, we begin to recognise the alphabetical pattern in the sequencing of these word-image photographs. The photographs present signs for ‘Needle', ‘Office', ‘Pal', for example; appearing in alphabetical order. The pattern recognition of the sequence has the effect of pulling the expectancy of the next, so that each subsequent image-text photograph builds to a kind of alphabetical mantra.

The stability of this textual pattern begins to disintegrate through the gradual substitution of image-texts for images of a different kind. Where we might expect to read the ‘B' in street signs for Barber, Bar, or Bonanza, we're presented with a short film sequence of a frying egg. Further substitutions occur: ‘O' becomes a bouncing ball; ‘X' becomes fire; ‘L' becomes a child swinging, until the pattern losses its sense of textual coordination entirely. In this way, a film such as Zorn's Lemma can be understood as a test of reciprocity in the exchange of language and images; ultimately, a zero sum game that reveals nothing other than the structure of their interdependency.

Another film that gives example of Frampton's compounding of literary and photographic narratives is (nostalgia), produced in 1971 with the assistance of friend and fellow filmmaker Michael Snow, who provides the voiceover for the film. Featuring a sequence of black and white photographs taken by Frampton, placed upon a ring-burner until they shrivel and burn, (nostalgia) corresponds directly to Frampton's previous incarnation as a still photographer. Furthermore, a voiceover recalls stories and anecdotes that relate to the photographs, in the context of Frampton's experiences in New York City (scripted by Frampton, spoken by Snow).

It soon becomes obvious that the photograph that the voiceover describes is not the photograph presented, but the description of the image to follow. Not only does this cause a temporal disconnection between language and image, but the viewer comes to rely on expectations of the next image by way of a description that precedes it; meanwhile the present image burns. As Rachel Moore has written in her book dedicated to the film, "the burnt photograph spent by language that quivers in front of us, registers this fall precipitated by language."

Both Zorn's Lemma and (nostalgia) give example of how language was central to Frampton's filmmaking; not as a mere aspect, but as an integral and forming structure woven into the capabilities of photographic images and film. It is this that also provides the challenge to a book like On the Camera Arts, which may have otherwise taken the opportunity to establish an easy inroad to Frampton's work upon the 25th year anniversary of his death. Despite such warnings, the book succeeds in appropriately sustaining the torsion of Frampton's inquiries, while contributing greatly to contemporary and retrospective discourses on the development of film in the interceptive spaces of art.

Matt Packer

Another titan of the avant-garde is Hollis Frampton, who made some of the medium's seminal works before succumbing to cancer in 1984. Familiarity with Brakhage has been enhanced by accessibility, granted not only by the Criterion Collection's DVD and Blu-ray editions, but also by his influence on some well-known mainstream objects, such as the opening titles of David Fincher's Se7en. If we can get a handle on Brakhage by thinking of his work as consisting largely of his famous hand-painted films, or Window Water Baby Moving, Frampton's "flagship" work is either the multi-title "Hapax Legomena," or the 59-minute Zorns Lemma. Components of "Hapax" include Special Effects, in which a dashed white rectangle rotates against a black background, Poetic Justice, which tells an erotic almost-story through a series of script notes as they are set down on a table between a cactus and a coffee cup. There's also Critical Mass, in which a couple's argument is transformed into a Möbius strip of repetitions and backtracks.

Once seen, Frampton's films, often deceptively simple in concept and setup, become singular and indelible, his uncanny intuition emerging from the most basic ruptures and rearrangements. Manual of Arms, one of his earliest surviving works, pays tribute to a close circle of friends and intimates in his sparsely adorned loft space. Partly a set of image studies, Manual of Arms opens with a series of faces, one at a time, against a pool of black and half-shadow, calling to mind the trope of personality-illustrative cast introductions from silent movies. Eventually, the series of close-ups gives way to full-body portraiture; each friend gets a different editing and camera-movement pattern, recalling Brakhage's Two: Creeley/McClure, in which the Mothlight filmmaker gave two friends custom-fitted cine-portraits.

There's an anarchic affection with which Frampton commits violence to forms, and to our gaze—breaking open familiar concepts and putting them back together in odd ways. In many cases, the movie will take place outside the "movie," in a kind of conceptual dialogue with the viewer using elemental cues, mimetic codes, and memory prompts. One of several great masterpieces is (nostalgia), in which the off-screen voice of confederate Michael Snow narrates a series of Frampton's photographs (speaking as Frampton, in the first person)—as each picture catches fire on a hot plate. Sometimes the violence is optical, as when Frampton deploys flashes of color and light, the barest, most incidental collisions of photons and emulsion. In The Birth of Magellan: Cadenza I, Frampton crosscuts against three radically different progressions of story and/or image (a bride, with or without the groom, on a park bridge, posing for the wedding photographer; a red dot exploding from a white background; a primitive silent comedy where a man surreptitiously removes a woman's skirt), less to tell a story than to build, in the Eisenstein manner, meaning through discordant juxtapositions. The resulting super-form, as it plays out, suggests feelings as varied as puerile "gotcha!" humor to apocalyptic sadness, the viewer's metamorphosing response helped along by Frampton's preferred mechanisms of repetition and rudimentary signifiers—like a canned laugh track.

As autobiographical as a thumbprint, Frampton's body of work is largely grouped by the various, ambitious projects he worked on—namely the seven-part Hapax Legomena and the Magellan cycle. These projects indicate not only a fascination with calendars and other organizing principles, but an eye for overall presentation, a kind of avant-garde showmanship. He was a cartographer who drew both the map and the undiscovered country, and his work reflects a conscious attitude toward audience contemplation, but also a refusal to let them absorb his ideas passively. In one of the one-minute "Pans" he made to accompany the Magellan series, there's a frame-by-frame crosscut between a bright, cloudy sky and a dark, cloudy sky that produces a strobe-like flash; in another, a glass bead oscillates before the camera, as if to simultaneously induce hypnosis and shake the viewer awake.

If Peter Kubelka is the kind of structural filmmaker whose effects are produced by the precise mathematical relationships between shots, as well as (equally precise) dissociative relationships between image and sound, the force of Frampton's structural ideas are balanced by a wanderer-gatherer instinct, and an overwhelming, architectural ambition, a desire to create epic poems, with cornerstones of brief, Lumière-esque pulses, epics that are only in part animated by some kind of systemic algebra. It's unlikely you will come across a filmmaker whose work creates in the viewer such a strong equilibrium of sudden, brutal displacement with an exhilarating freedom of travel; you are jostled, you contemplate, you wander across a continent in which all is unexplainable, yet familiar.

Unlike Brakhage, sound (music, voice, and effects) was often vital to Frampton, and Criterion's set is, in part, a document of the sound recording and editing means available to an independent filmmaker working from the 1960s through the early '80s. Given the limits of technology, Criterion's mono soundtrack presentation is impeccable.

A Hollis Frampton Odyssey: Nostalgia for an Age Yet to Come

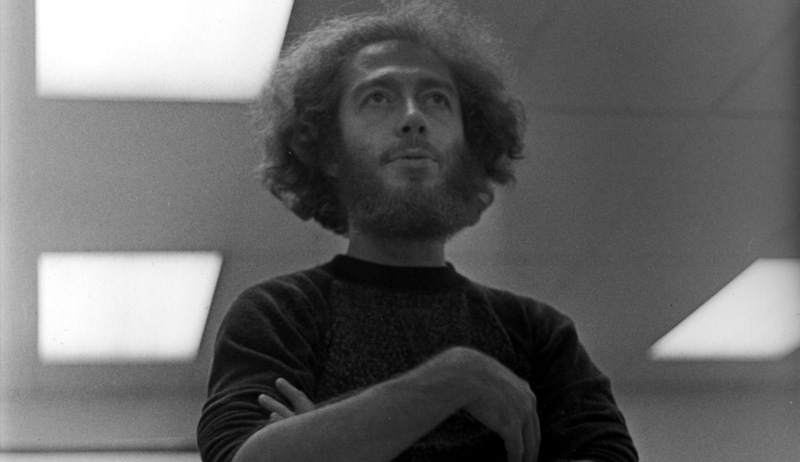

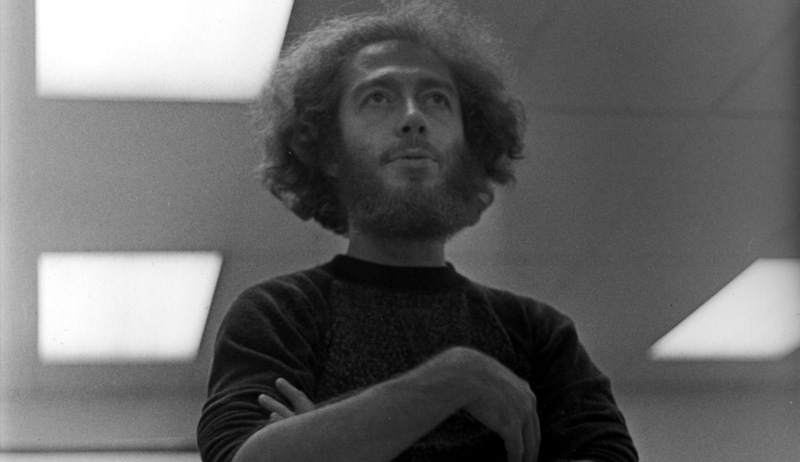

Among the most widely seen photographs of Hollis Frampton is one of him as a young man, a self-portrait taken in 1959, if we are to trust the narration he composed to accompany its inclusion in his 1971 film (nostalgia). In the image, Frampton sits against a neutral backdrop, looking to his right, as if intently scrutinizing something just outside the frame. His shoulders press forward, suggesting that his unseen hands are resting crossed in his lap, and he sports a neat dark jacket and tie, their conservatism offset by a beatniky beard and hair that would have been considered longish in the 1950s, combed back into a Victorian wave. “As you see, I was thoroughly pleased with myself at the time, presumably for having survived to such ripeness and wisdom, since it was my twenty-third birthday,” the narrator says in (nostalgia). “I focused the camera, sat on a stool in front of it, and made the exposures by squeezing a rubber bulb with my right foot.”

When he took this photo, Frampton was working as an assistant in a commercial photography studio in New York, where he had moved the previous year, and was sharing an apartment with sculptor Carl Andre, who had been his high school classmate at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts (as had painter Frank Stella, with whom they would share studio space). Due to his dispute over the necessity of a required history course, Frampton had failed to graduate from Andover, thus forfeiting a scholarship to Harvard and instead attending Western Reserve College in Cleveland. While there, he struck up a correspondence with Ezra Pound, who was then a mental patient at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. Frampton—who was writing poetry at the time—left Cleveland to move near Pound, visiting him daily in the hospital, while the older poet continued to compose The Cantos, his sprawling epic, dense with reference and allusion, which would remain unfinished at his demise. Pound’s high modernism would serve as a touchstone for Frampton, as would the parallel modernisms of Marcel Duchamp, Jorge Luis Borges, and James Joyce. Ironically, Frampton, too, would embark upon an ambitious, large-scale project—the proposed thirty-six-hour film cycle Magellan—that would be cut short by his death from cancer in 1984, at age forty-eight.

Another oft reproduced image of Frampton is entitled Portrait of Hollis Frampton by Marion Faller, Directed by H. F. It was taken in 1975 by Faller, the photographer with whom Frampton lived during the last thirteen years of his life. The picture shows him staring, eyes wide and pupils contracted, almost into the lens of the camera, his hands raised beside his head, palms outward. In the darkness, a horizontal slit of light draws a line across his eyes and onto the middle of both of his hands. His hair is wilder than at age twenty-three—the light beam illuminates shaggy bits jutting out from his temples—and his beard is fuller, now flecked with white. The setup cannily alludes to the mechanics of both photography and cinema, of light projected and recorded, but in its alien strangeness resembles a promotional still from a science-fiction movie. It almost appears as if the light is not so much being thrown on him as projected outward from his eyes and hands. In the earlier self-portrait, Frampton seems relatively staid, as if looking toward the past, trying to emulate an early twentieth-century poise. But here, at age thirty-nine, he stares as if into a vision, ready to walk forward into the unknown, ecstatic.

In the time between these two photographs, Frampton had established himself as one of the foremost members of the American avant-garde, part of a new generation of artists who came to fruition in the late 1960s, dramatically shifting the terms of both experimental film and the intellectual thinking on cinema as a whole. By the end of his career, he had completed close to one hundred films (including the individual one-minute Pans for Magellan) and numerous photographic series; helped establish the pioneering Digital Arts Laboratory at the Center for Media Study at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1977; published Circles of Confusion: Film, Photography, Video—Texts 1968–1980, his influential collection of theoretical essays and other writings that had originally run in Artforum, October, and elsewhere; and been honored with retrospectives at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At a time when many of his filmmaking colleagues still kept their distance from newer electronic media, he not only embraced and wrote about video but also delved into xerography and computer programming.

In standard histories of experimental cinema, Frampton’s work is usually considered part of “structural film,” a category invented by P. Adams Sitney in a 1969 essay that would later be revised into a chapter of his landmark 1974 study Visionary Film. Sitney coined the term to describe what he saw as a new tendency in the American avant-garde, typified by the films of Frampton as well as those of Michael Snow, George Landow, Tony Conrad, and others. “Theirs is a cinema of structure,” Sitney wrote, “in which the shape of the whole film is predetermined and simplified, and it is that shape that is the primal impression of the film”—a sharp divergence from the work of an older generation of filmmakers, including Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and Kenneth Anger, who, in his view, had progressed over time toward a greater internal complexity of form. He compared structural film to minimalism in the visual arts and serial composition in music, contemporaneous movements that likewise stressed formal reduction and repetition. Frampton, however, rejected Sitney’s periodization, denouncing “that incorrigible tendency to label, to make movements, [which] always has the same effect, and that effect is to render the work invisible.”

Nevertheless, Frampton did agree that a new sensibility was afoot. Describing his own development, he recalled that “there was something called the [Film-Makers’] Cinematheque in New York, which became a kind of hangout. I met other people who were trying to make films: Joyce Wieland, Michael Snow, Ken Jacobs, Ernie Gehr after a while, although he was somewhat younger. Later on, Paul Sharits, who was at the time living in Baltimore.” These are all figures whose work Sitney classified under structural filmmaking, but Frampton saw their shared project as a more expansive one. “There existed at least for a time, and that time lasted for some years in New York City, a kind of constant contact between us. One might almost—almost—venture to call it a sense of being united in some way, probably by the conviction that there should be good films. Preferably, films so good they hadn’t been made yet. That the intellectual space open to film had not entirely been preempted.”

Regardless of Frampton’s distaste for labels, one can productively think about his films in terms of a simplification of elements in favor of an overall, predetermined shape. This is particularly so in his earliest surviving works, from Information (1966) to Zorns Lemma (1970). In this phase of his filmmaking, Frampton was interested in taking apart cinema by reducing it to its most basic, constitutive parts—sound, image, movement, editing—and then using these elements to construct films whose unfolding takes on the quality of a mathematical formula or puzzle. Later in his career, he would describe his concerns during this formative period as the “rationalization of the history of film art. Resynthesis of the film tradition: ‘making film over as it should have been’” and the “establishment of progressively more complex a priori schemes to generate the various parameters of filmmaking.” His play with the possible relationships between sound and image in works like Maxwell’s Demon (1968), Surface Tension (1968), and Carrots & Peas (1969) would culminate in the abecedarian structure of Zorns Lemma. The films’ titles alone convey his interest in importing concepts from the sciences into art, though never in a straightforward way; he once said, “I’m a spectator of mathematics like others are spectators of soccer or pornography.” His goal was a more epistemological one. “Eventually,” he would later write, “we may come to visualize an intellectual space in which the systems of words and images will both, as [filmmaker, poet, and founder of New York’s Anthology Film Archives] Jonas Mekas once said of semiology, ‘seem like half of something,’ a universe in which image and word, each resolving the contradictions inherent in the other, will constitute the system of consciousness.”

To speak of Frampton’s films as merely structural riddles or philosophical proposals, however, fails to take into account their pleasurable and poetic nature. The gamelike qualities of his films prove playful rather than didactic and always retain a residue of enigma. And he is more of a storyteller than the structural label would suggest. His films are told with an erudite wit, an often stark beauty, and deep emotional resonance. This last quality is one that sets him apart from many of his “structural” fellow travelers and is most apparent in his only completed film cycle, Hapax Legomena (1971–72), a seven-part sequence including three of his best-known works, (nostalgia), Poetic Justice (1972), and Critical Mass (1971). Throughout the cycle, Frampton continually reveals intricate relationships between time and memory, word and image. He called the project “an oblique autobiography, seen in stereoscopic focus with the phylogeny of film art as I have tried to recapitulate it during my own fitful development as a filmmaker.” This aspect is most explicit in (nostalgia) but is also evident, in a more buried way, in Critical Mass, which creates hypnotic rhythms from footage of a woman and a man engaged in a heated argument—completed when Frampton was working through the tumultuous end of a six-year marriage.

The “phylogeny of film art” that Frampton mentions relates to a further concept underpinning his work as a whole, what he called a “metahistory” of cinema, by which he meant the creation of a specific body of films that would serve as an instructive metaphor for the whole history of film. “The history of cinema consists precisely of every film that has ever been made, for any purpose whatsoever,” he wrote. “The metahistorian of cinema, on the other hand, is occupied with inventing a tradition, that is, a coherent, wieldy set of discrete monuments, meant to inseminate resonant consistency into the growing body of his art. Such works may not exist, and then it is his duty to make them.” His unfinished Magellan project would have been his fullest realization of this concept. Planned around the conceit of Ferdinand Magellan’s global circumnavigation, it was to comprise a liturgical calendar of more than eight hundred films, with Lumière-inspired miniatures on most days and longer works on equinoxes, solstices, and other special dates. Within this solar epic, Frampton envisioned numerous “subsections and epicycles,” completing a macrocosmic engine reminiscent of an astrolabe’s nested gears or a computer program’s subroutines—the latter suggested by Frampton’s dot-matrix-printed schedule from 1978, “CLNDR version 1.2.0,” with each day numbered like a line of code.

As Magellan’s algorithmic aspects illustrate, Frampton was concerned not only with cinema’s history but its future as well. In numerous writings, he conjectured that the technology of film had already reached its point of obsolescence, pinpointing this moment at the invention of radar, rather than the more obvious rise of television. The machine age apparatus created by the Lumières and Edison would someday be seen as merely an early phase of an as-yet-unnamed technology of moving-image-making that he would variously term “the camera arts” or “film and its successors” or “photograph-film-video-computer.” And this system was, in turn, an outgrowth of much older forms, like painting and music. He suggested that cinema would endure past its death, albeit transmuted, through this larger trajectory.

Or to put it another way, as Frampton did in his notes on Gloria! (1979), a work dedicated to his grandmother: “The last time I saw my grandmother, she said to me: ‘We just barely learn how to live, and then we’re ready to die.’” The film, however, depicts a story based on the ballad “Finnegan’s Wake,” wherein a dead body rises from its casket to dance at its own funeral. Surely, Frampton would have found wry amusement in this collection of his work, which replicates his films via encrypted lines of code and releases them back into the world as digital ghosts.

A Hollis Frampton Odyssey (1966-1979) [The Criterion Collection] - by Bryant Frazer

The avant-garde in film has always had an uneasy relationship with home video. Grainy old VHS tape of works by luminaries like Bruce Conner or Kenneth Anger might have made the texts themselves available for more careful study by a larger audience, but the picture quality compromised the work tremendously. The arrival of DVD technology allowed for a better visual representation, yet brought with it certain dangers. For one thing, there's a moral issue: Filmmakers who had objections to the commodification of art and culture were put on the spot as their once-ephemeral films were transferred to a new medium that was easy for an individual consumer to purchase and own. There's also an aesthetic issue. No matter how close a video transfer gets to the visual qualities of a projected film--and a good transfer to Blu-ray can get very close indeed--a video image is not a film image. For avant-garde filmmakers, and especially for so-called "structural" filmmakers like the late Hollis Frampton, for whom film itself was subject, text, and subtext, the difference is key.

The Criterion Collection kept the distinction at front of mind in its creation of A Hollis Frampton Odyssey, its new DVD and Blu-ray release presenting a sample of Frampton's work for home-video posterity. Open the case and slide out the thick, 44-page booklet and you're greeted by an inside-front-cover spread displaying a Xeroxed scrap of paper on which is scrawled the declaration, "A film is a machine made of images." Read on, and you'll find a short essay (by film preservationist Bill Brand) on the challenges of translating Frampton's films to video masters, explaining how a first-generation print of Zorns Lemma was used to generate a noise floor* for the too-silent video presentation and describing the decision-making process that goes into allowing a scratch to be a scratch. Dig into the supplements and you'll find a recreation of a Frampton piece designed to be delivered in a room with a movie screen and movie projector called "A Lecture," in which Frampton--speaking through the recorded voice of fellow experimental filmmaker Michael Snow--describes the film projector as an "infallible," "flawless" performer of "a score that is both the notation and the substance of the piece." The setting will be familiar to anyone who's ever sat in the dark, luxuriating in the strobe of images flashing on the screen, revelling in the clackety-clack of the projector at the back of the room.

Frampton didn't arrive in that dark room by fiat. He first tried his hand at painting, then still photography; it took him a while to settle on filmmaking. A Hollis Frampton Odyssey begins with the first of Frampton's films to be publicly screened (a handful of earlier films were "projected to death" but not shown to the public, according to liner notes by Bruce Jenkins) and ends with selections from Magellan , the massive, ever-growing film cycle Frampton left incomplete upon his death from cancer in 1984, at the age of 48. In between, it proffers a sampling of Frampton's work, framed with generous supporting material--various text-based essays as well as audio recordings of Frampton himself discussing each of the films here--that presents it in the context of Frampton's career and his intense, theoretical style.

Let's go back to that term, "structural film," and to Frampton's place in the canon of American avant-garde filmmakers. Criterion first dipped its toes into the avant-garde with the release of By Brakhage, a DVD collection of Stan Brakhage's films later expanded for Blu-ray, and the decision to follow Brakhage with Frampton isn't simply one of convenience. Brakhage and Frampton were contemporaries, although Brakhage was making films in the 1950s and Frampton didn't start until 1962. Nevertheless, P. Adams Sitney, whose Visionary Film is quite literally the book on the subject, saw the two men as coming from quite different traditions. In Sitney's eyes, Brakhage came from a Romantic tradition established by Maya Deren and eventually created the "lyrical film." One response to Brakhage's lush, everything-in-its-place lyricism was Andy Warhol, whose strategy of putting his camera on a tripod and letting it run until it was out of film could be read as a gentle mockery of Hollywood conventions or as an infuriating parody of the avant-garde. And it's out of Warhol's long-take, fixed-camera provocations that what Sitney dubbed structural film was born.

You can see Warhol's influence in the earliest Frampton films collected here. His first publicly exhibited work, Manual of Arms

(1966), which animates some of Frampton's talented friends (such as

dancer Twyla Tharp and filmmakers Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland)

through elaborate montage techniques, can be read as a pointed

back-at-ya response to Warhol's famous screen tests. And his wry Lemon

(1969), which documents the play of light cast by a lamp being moved

around a plump yellow fruit, feels like a miniaturized burlesque on

Warholian endurance tests like the six-hour Sleep or the eight-hour Empire. Actually, I read it first as a parody of 2001: A Space Odyssey. There is something truly grand about Lemon

in a declaration-of-principles sense. I imagined Frampton raising a

middle finger to the commercial film industry and declaring, "Hey

fuckers, I've got sex and death and the whole shebang in my film and

it's just a goddamned lemon." (In the supplementary material, Frampton

admits he selected the most voluptuous lemon he could find at the

grocery. He says it looks like a breast, and some viewers apparently see

a phallus just before the skin of the fruit vanishes in the darkness.)

You can see Warhol's influence in the earliest Frampton films collected here. His first publicly exhibited work, Manual of Arms

(1966), which animates some of Frampton's talented friends (such as

dancer Twyla Tharp and filmmakers Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland)

through elaborate montage techniques, can be read as a pointed

back-at-ya response to Warhol's famous screen tests. And his wry Lemon

(1969), which documents the play of light cast by a lamp being moved

around a plump yellow fruit, feels like a miniaturized burlesque on

Warholian endurance tests like the six-hour Sleep or the eight-hour Empire. Actually, I read it first as a parody of 2001: A Space Odyssey. There is something truly grand about Lemon

in a declaration-of-principles sense. I imagined Frampton raising a

middle finger to the commercial film industry and declaring, "Hey

fuckers, I've got sex and death and the whole shebang in my film and

it's just a goddamned lemon." (In the supplementary material, Frampton

admits he selected the most voluptuous lemon he could find at the

grocery. He says it looks like a breast, and some viewers apparently see

a phallus just before the skin of the fruit vanishes in the darkness.)

I like Lemon a lot, but it doesn't suggest the rigor that is to come. The early Frampton film that most portends the occasional opaqueness of his approach is Maxwell's Demon (1968), named after a thought experiment created by the Scottish physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell. Essentially a found-footage piece, it intercuts snippets of an exercise film with flashes of pure colour and tinted shots of ocean waves underscored by the sound generated by the physical passage of film sprocket holes over a projector's audio pickup. The titular demon is a tiny character who regulates the movements of gas molecules (in contravention of the second law of thermodynamics, which claims that entropy always increases), and Frampton describes the piece in his comments as "an homage to the notion of a creature who deals with pure energy." Maxwell is also, as it turns out, the father of modern red-green-blue colour theory, and the first to demonstrate the connection between light and electromagnetic waves.

I'm not sure what an audience would make of this sans context. Even with Frampton's explanatory comments on the Blu-ray (where he compares Maxwell's gas molecules to excited pigs), Maxwell's Demon sent me scurrying to WIKIPEDIA, where I learned a wealth of information about 19th-century physics that may serve me better in the long run than Frampton's film by itself. But that's his mode of expression. Brakhage had the sensibility of a poet taking as his great subject the human visual system. By contrast, Frampton comes across as more of an engineer.

Another early film, Surface Tension (1968), is quite charming. It opens with a title superimposed over an ocean wave (a leftover from Maxwell's Demon?), followed by a slightly difficult introductory section featuring sped-up footage of a gent decked out in button-up shirt, vest, and scarf leaning against the sill of an open window, gesturing and speaking, although the soundtrack carries only the shrill sound of a telephone ringing in an otherwise quiet room--the repetitive, unsettling noise reminding us of what we're not hearing. The moving image drops to a normal speed briefly whenever the chap briefly stops speaking and reaches down to shut off and set a timer. Next, a time-lapse walking tour of Manhattan begins on the Brooklyn Bridge and ends, two-and-a-half minutes later, in the middle of Central Park. It's soundtracked by spoken German, something I took to be part of the missing speech by the well-dressed chap from the first section--a feeling confirmed by the sudden interruption of the narration by an obnoxious buzzer. The third section depicts a goldfish in a tank on the beach, waves lapping at the glass as text fragments appear on screen, apparently snippets drawn from the German monologue heard during the previous chapter. The mismatch of sound and image seems to be the primary subject here--the distance between the visual of the German speaking in the first section, the (presumably) incomprehensible audio of his speech in the second, and the appearance of a few of his words as fragmented signs in the third. Two more "early films" are collected here: Process Red (1966), another experiment with highly caffeinated montage techniques, and Carrots & Peas (1969), an exercise in stop-motion animation and colour manipulation.

These works are thought-provoking to greater and lesser degrees, but it all amounts to throat-clearing before the appearance of Frampton's first major work, Zorns Lemma (1970). Named for a principle from set theory I can scarcely wrap my poor head around, the film echoes Surface Tension in its three-part structure but is far more expansive in its scope and strategy. It begins with readings from a Bible-derived, alphabet-oriented young-readers text called the Bay State Primer and closes with an image of a couple and a dog walking across a snowy landscape, away from the camera, accompanied by a reading from Robert Grossetete's "On Light, or The Ingression of Forms". In between, there's a longish (~45 minute) segment in which single words, each one part of a moving picture of a sign taken by Frampton somewhere on the streets of New York City, appear on screen for one second each. The overall effect is dizzying (this segment of the film contains 2700 cuts!), but not unpleasant, especially as you figure out what the movie's up to. With Surface Tension, Frampton spoke of his desire to avoid merely displaying an ordered collection of still photographs (his printed photos appeared "perfectly dead" when rephotographed with a movie camera, he noted) or to create "a poem" (by deliberately placing images in provocative juxtaposition). Instead, he employed a randomizing technique to assemble the images that reminded me a little bit of the "cut-up" literature popularized by William S. Burroughs in the 1970s. I gather there was quite a bit of critical eye-rolling when Zorns Lemma screened at the New York Film Festival (it elicited a hilariously stodgy NEW YORK TIMES review that concludes with a shout-out to the Andrews Sisters), but the film seems pretty accessible by avant-garde standards.

Viewers who may be baffled by Zorns Lemma's semiotic ambitions--it ponders the possibilities of a visual alphabet, images replacing letters in a kind of cinematic iconography--may still find pleasure in its elaborate construction, or just in Frampton's evident skill as a photographer and incidental documentarian of vintage New York City signcraft. But for filmmakers in the purely visual tradition of Brakhage, Zorns Lemma was a salvo. Frampton's fastidious randomization of his own work was a repudiation of the meticulous visual sense and intellectual montage that drove much of the American avant-garde, and Brakhage himself was inspired to repudiate it with an answer film, The Riddle of Lumen (1972), with looser, free-flowing visual and editorial rhythms that offered a shambolic counterpoint to Frampton's staccato lockstep. (Sadly, Lumen is absent both here and in either volume of Criterion's earlier By Brakhage release. It can, however, be found on the National Film Preservation Foundation's two-disc Treasures IV: American Avant-garde Film, 1947-1986.) Another issue separating Frampton from Brakhage was that, among the standard-bearers of structural film (see also: Snow and Ernie Gehr), Frampton was the most interested in language. Indeed, in words that suggested a typically playful double meaning, Brakhage once said Frampton "strains cinema through language." The attention he paid to words, letters, signs, and symbols, and the elaborate and essentially randomizing systems he devised for dictating how a film would be edited, were anathema to filmmakers of the Brakhage school, for whom human instincts and imperfections (the wobbly handheld camera, the shaky mark scratched by hand in a film's emulsion) were crucial components of hand-crafted visual expression.

On a more personal note, it turned out that the film functioned as broad autobiography, with the first section representing Frampton's Protestant upbringing; the second section representing the long process of creative evolution and interaction with his urban environment; and the final section functioning as a prophecy of his coming move out of the city in 1974, after accepting a job teaching in Buffalo. Those who are skeptical of the pretensions evident in the title may, perhaps, enjoy it on this level. But it's very pleasurable, still, to sit quietly through the film's duration, watching the edit fall into place with the sure rhythms of a powerful machine. In its carefully-engineered simultaneous conjuring of entropy and orderliness, Zorns Lemma might be the quintessential structural film.

It was in the later Hapax Legomena series that Frampton's paths of inquiry extended into utterly new territory. The title itself refers to that sense of not knowing what the hell to make of something--it's Greek for words that appear only once in a given text or set of texts. In the case of an ancient text or translation from a forgotten language, a hapax legomenon can pose a special challenge for scholars and translators, who may be unable to discover the meaning of the word based on its appearance in only one context. Frampton's Hapax Legomena begins with (nostalgia) (1971), an apparently autobiographical work that folds perceptions of time in on themselves by returning to the discontinuity of sound and image he explored in Surface Tension. The film depicts a series of Frampton's still photographs placed on a hot electric element that slowly disfigures, chars, and destroys them as the camera rolls. On the soundtrack, a voice describes a different image--actually, the image that will appear next in the series. Once you figure out what Frampton is up to, the piece becomes an unusual brain exercise. You're listening to the voiceover narration because you know it will tell you something about the picture you're about to see. At the same time, you're scrutinizing the picture on screen, trying to remember what you've already been told about it. (There are other nooks and crannies in the structure Frampton builds here. For one thing, the ostensibly first-person narrative is not read by Frampton but by his friend Michael Snow--at one point, Snow reads Frampton's description of a poster he made for one of Snow's shows, part of a passage that concludes with Frampton's lament, which becomes more poignant in this context: "I wish I could apologize to him.") And, by taking the immolation of Frampton's own work as a subject, (nostalgia) made me wonder if he was inspired by John Baldessari's conspicuous act of burning everything he had made pre-1970 as a statement of dissatisfaction with his own art.

Equally mind-expanding is the next film in the Hapax series, Poetic Justice (1972), the concept of which at first seemed unbearably trite to me. It opens on a round, wooden tabletop featuring a cactus, a cup of coffee, and a stack of paper. After a cut several seconds in, the stack of paper disappears and single sheets, consecutive pages of a screenplay, start appearing on the table. As I watched, I couldn't help but start to imagine the film described by the screenplay being made. The pages insist that the film is about "you" (meaning me, the viewer) and "your lover" (meaning, well, whomever I'd like, I suppose). But there's also a "me" in this screenplay--references to "my hand," holding a variety of photographs--that brings the script's author into the picture.

The

script has me climb on a chair, and suddenly I'm worried. Am I going to

hang myself? Soon, my lover puts a blindfold over my eyes, and I wonder

what sort of movie this is, anyway. Several more pages, and the bedroom

door is closed, my lover lies supine on a bed, and I'm starting to

panic. A few more pages. Why is Hollis Frampton watching me fuck?

The

script has me climb on a chair, and suddenly I'm worried. Am I going to

hang myself? Soon, my lover puts a blindfold over my eyes, and I wonder

what sort of movie this is, anyway. Several more pages, and the bedroom

door is closed, my lover lies supine on a bed, and I'm starting to

panic. A few more pages. Why is Hollis Frampton watching me fuck?

I can't think of any film that seems to work on more layers at one time: there is the film itself, there is the image represented by the screenplay pages, and then there is the image their words suggest, which lives only in the mind of the audience and will be different for each viewer. There are references to photographs that become frames within the frame of the imagined film, and later the script describes a large bedroom window, outside of which are, variously, hyenas, wrestlers, mountaineers, and (magnificently) the rings of Saturn, looming--more imagined images framed within an imagined image. Using photographed words to conjure a never-to-be-photographed image, Poetic Justice is just about the most conceptually perverse art film I can imagine--and I don't think I'll ever forget the dreamy, nightmarish moving picture I fashioned for myself as it unspooled. I don't know whether Frampton found himself in a particularly generous mood when he made this, but I'll always think of it as a work that unlocks the imagination of the audience in a tremendous way.

I'm less enamoured of Critical Mass (1971), largely because I find it unbearably unpleasant to sit through. A filmed record of an improvised argument between two actors playing the role of a couple, it's a showcase for Frampton's editorial technique--he cuts up three different copies of the scene, then edits them linearly to give the scene a repetitive stutter-step quality that extends the already nigh-intolerable duration of the shouting match. I felt about Critical Mass much the same way I feel about the neighbours just past paper-thin sheet rock having a knock-down drag-out after 11 p.m., and it makes me want to pound on the walls and/or drink myself into a stupor. This may be the intended sensation. As a work of pure vision and craftsmanship, I'll bet it made the grade in 1971, when every edit had to be painstakingly made by hand. Frampton, whose wife left him in the months between the shooting and the editing, must have felt each cut in his bones.

Frustratingly, the four films that make up the rest of Hapax Legomena

are not included here. Granted, these first three are the ones that

generate all the attention, but Kenneth Eisenstein's liner notes for

Criterion offer a tantalizing glimpse of works said to employ

"television, video, and...electronic music." Still, we do get an

indication of where Frampton's head was going in the final section of

the disc, which collects films from his mammoth unfinished Magellan project. In his essay included in the Blu-ray booklet, Magellan

expert Michael Zryd says the project was to involve "roughly 830"

separate films shown on a special screening schedule covering 371

consecutive days. (Critic Ed Halter, who has his own booklet essay here,

has written elsewhere that Magellan would be made up of "about 1000" films.) Frampton had barely gotten started on Magellan

before he died, completing something like eight hours out of a

projected 36. The sampling chosen for Criterion's disc includes 17

separate films totalling a little over an hour, but 12 of them are tiny

little one-minute vignettes called "pans" (three of these are only

visible when they appear as part of the disc's menu animations, but you

can dig out clean versions if you rip the disc). One of them features

three coloured slips of paper tacked to a wall, another shows a

cornfield, another depicts the beheading of a farm animal, etc.

Frustratingly, the four films that make up the rest of Hapax Legomena

are not included here. Granted, these first three are the ones that

generate all the attention, but Kenneth Eisenstein's liner notes for

Criterion offer a tantalizing glimpse of works said to employ

"television, video, and...electronic music." Still, we do get an

indication of where Frampton's head was going in the final section of

the disc, which collects films from his mammoth unfinished Magellan project. In his essay included in the Blu-ray booklet, Magellan

expert Michael Zryd says the project was to involve "roughly 830"

separate films shown on a special screening schedule covering 371

consecutive days. (Critic Ed Halter, who has his own booklet essay here,

has written elsewhere that Magellan would be made up of "about 1000" films.) Frampton had barely gotten started on Magellan

before he died, completing something like eight hours out of a

projected 36. The sampling chosen for Criterion's disc includes 17

separate films totalling a little over an hour, but 12 of them are tiny

little one-minute vignettes called "pans" (three of these are only

visible when they appear as part of the disc's menu animations, but you

can dig out clean versions if you rip the disc). One of them features

three coloured slips of paper tacked to a wall, another shows a

cornfield, another depicts the beheading of a farm animal, etc.

The five other films range from around five minutes to a half-hour in length. The Birth of Magellan: Cadenza I (1977) is the first instalment of Magellan and thus functions as a sort of overture for the entire project. It opens with the image of a letter A carved into stone, followed by the sound of an orchestra tuning, then incorporates footage of a wedding Frampton shot in a park in Puerto Rico--the sound, again, of sprocket holes--and scenes from an American Mutoscope and Biograph silent film, A Little Piece of String. Sitney sees in this formulation one of Frampton's occasional embedded nods to Duchamp via his famous artwork The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even. Speaking of bare, Ingenivm Nobis Ipsa Pvella Fecit, Part I (1975) consists of motion poses by a nude young woman (reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge's serial photography), edited in a repetitive, forward-and-back stutter-step style that immediately recalls Critical Mass but feels to me unmistakably like the image from a videotape being wound back and forth with a jog-and-shuttle wheel. (I have no idea if Frampton had access to that kind of video-editing machine in the mid-1970s. Perhaps he was simply prescient of new ways of looking at footage.)

I've mentioned Brakhage repeatedly, and that's partly because that's where A Hollis Frampton Odyssey ends up--Brakhage positively haunts the following two Magellan selections here. Magellan: At the Gates of Death, Part 1: The Red Gate 1, 0 (1976) was shot at a human anatomy lab at the University of Pittsburgh and clearly functions in part as a response to Brakhage's famous autopsy film The Act of Seeing with One's Own Eyes, which was shot at the Pittsburgh coroner's office. (Sally Dixon, a curator at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Art, was a friend of the avant-garde and worked as a liaison between Brakhage and Frampton and various public institutions.) Where Brakhage's filmed encounter with death itself was harrowing and profoundly humane, Frampton's images of body parts seem, to me, more morbid and grotesque. (For his part, Frampton once noted a certain "didacticism" in Brakhage's film--an odd way to think about The Act of Seeing with One's Own Eyes, if you ask me, but maybe that's why the Brakhage never gave me nightmares while Frampton's version squicks me out completely.) Next up is Winter Solstice, which assembles images photographed at a U.S. Steel facility in Pittsburgh into a cascading series of essentially abstract compositions in fiery red, yellow, and black. Although Frampton still has a great artist's eye for shape and colour in motion, the harshness and relative monotony of Winter Solstice made me long for Brakhage's more lyrical facility with texture and light.

It's all redeemed, however, by the final film completed for Magellan, Gloria! (1979). Gloria! quotes from two different silent films referring to the 19th-century

ballad "Finnegan's Wake," about an Irish drunkard, presumed dead, who

wakes up during his own funeral. Those scenes bookend Frampton's

observations on his relationship with his grandmother ("She kept pigs in

the house, but never more than one at a time"; "She gave me her teeth,

when pulled, to play with") typed out on a green-and-white computer

screen. The penultimate image is that of a "resurrected" Finnegan

dancing the exuberant jig of the undead. It's followed by a close-up of a

computer screen, on which appears, in glowing letters, a sober

dedication to Frampton's maternal grandmother, Fanny Elizabeth Catlett

Cross, who died in 1973. Like Frampton's best work, Gloria!

looks simultaneously backwards and forwards. It's excited about the kind

of image-making that will come to pass in the future, though it clearly

understands that death lives there, too.

It's all redeemed, however, by the final film completed for Magellan, Gloria! (1979). Gloria! quotes from two different silent films referring to the 19th-century

ballad "Finnegan's Wake," about an Irish drunkard, presumed dead, who

wakes up during his own funeral. Those scenes bookend Frampton's

observations on his relationship with his grandmother ("She kept pigs in

the house, but never more than one at a time"; "She gave me her teeth,

when pulled, to play with") typed out on a green-and-white computer

screen. The penultimate image is that of a "resurrected" Finnegan

dancing the exuberant jig of the undead. It's followed by a close-up of a

computer screen, on which appears, in glowing letters, a sober

dedication to Frampton's maternal grandmother, Fanny Elizabeth Catlett

Cross, who died in 1973. Like Frampton's best work, Gloria!

looks simultaneously backwards and forwards. It's excited about the kind

of image-making that will come to pass in the future, though it clearly

understands that death lives there, too.

Given the fundamental differences between projected film and home video, is Blu-ray an appropriate medium for a first encounter with this material? If nothing else, Zryd's liner notes indicate that Frampton was excited about the opportunity the then-emergent LaserDisc technology potentially afforded for personal consumption of the Magellan series. It's also interesting that DVD and Blu-ray allow viewers to fundamentally reshape his work, on a whim, allowing them to remake the films to their preferred specifications. About the first thing I did after watching Lemon was replay it at 120x speed, so I could get a better sense of how the light source was moving in its slow orbit around the fruit. And I'm hardly the only one to have pored over the middle section of Surface Tension, turning its frames into images rescued from a downtown Manhattan time capsule. Earlier this year, a NEW YORK TIMES writer blogged about it, transforming it into a viral sensation among cosmopolitan web surfers who would never otherwise stumble across Frampton's stuff. To this day, it's almost impossible to Google usable information on Surface Tension without getting caught up instead in one of several dozen reveries by aging baby boomers and others who get a nostalgic kick from the images. (Speaking of which, the images from the xerographic series excerpted here, By Any Other Name, are catnip for nostalgia buffs, featuring art from interestingly-branded grocery labels of the late-1970s and early-1980s.)

This isn't what Frampton intended, any more than it occurred to a 30-year-old Stan Brakhage that one day anyone with a fancy videogame console would be able to step through Mothlight, looking at the component bits of Rocky Mountain plant and insect life he assembled on splicing tape. But I think Frampton is likely to have anticipated it, and he might even have welcomed it. The long interview with Frampton that closes out this disc (it's a 20-minute excerpt from a 42-minute Video Data Bank interview conducted by filmmaker Adele Friedman in 1978 or '79) concludes with his observations about the coming transformation of visual media that would be ushered in by computer technology. The computer portended a revolution in "the image machine," he said, that would have farther-reaching consequences than the changes wrought by television, that most world-altering of early 20th-century technologies. At the time, he must have sounded like a starry-eyed crackpot. The digital video revolution didn't really begin until after Frampton's death, and that's a shame. He seemed well-equipped to, if not make something truly new out of DV, at least have a profound influence on video artists. (You could argue that Peter Greenaway's pioneering use of the Quantel Paintbox on Prospero's Books and The Pillow Book was a fairly straightforward extension of Frampton's legacy into narrative film.) That's just Frampton as prophet, instinctively understanding and anticipating the drastic transformation that moving pictures reeled towards as they approached the end of their first century.

Criterion's Blu-ray is a definitive but necessarily incomplete overview of Frampton's work--definitive because the films clearly got The Criterion Treatment and it feels like a miracle to see them at home with such clarity and with so much attention paid to maintaining the correct look. The 16mm source material was scanned at 2K, enough resolution to effectively capture all of the picture information; the image has soft edges, grain is obvious but muted, and many artifacts of the elements themselves have been tactfully left unmolested. Audio has received a 24-bit remaster from the original source elements in addition to being worked over with Pro Tools, but, again, with care not to alter the aural quality of a screening from film.

Because I'm greedy, I want more material--at the very least, it seems like a shame that Criterion couldn't squeeze in the rest of the Hapax Legomena cycle--and trying to come to terms with Frampton is like falling down a rabbit hole as you discover the breadth of the man's intellectual concerns. I'd argue for an ideal release to be spread across two discs, allowing Hapax Legomena to be complete on the first one and for more of Magellan to be presented on the second. Then again, that would increase the financial pressures on both Criterion, which would be investing even more in an unknown commercial property, and on the Frampton estate, which has to be concerned about the dive in 16mm film rentals that any avant-garde filmmaker's DVD release portends, especially if it includes their most famous works in toto. And, of course, this platter already contains more than four hours of prime Frampton. I have no idea how the market has reacted to A Hollis Frampton Odyssey, though I hope sales are strong enough to encourage Criterion to keep assembling programs of this type, and to convince filmmakers that it's worth allowing their work to be released for home viewing. I know these digital images aren't film prints--and I can't be the only one who still misses the whirring of that movie projector--but they get us a good portion of the way there.