Julian Koster, član bendova Elephant 6, Olivia Tremor Control i Neutral Milk Hotel nastavlja raditi čudesni muzički džem napravljen neobičnim instrumentima. Dječja slikovnica za tužne izvanzemaljske bebe.

www.orbitinghumancircus.com

Julian Koster and Robbie Cucchiaro have spent the last four years bringing The Music Tapes' legendary live shows to living rooms, opera house stages, and everywhere in between-along the way garnering an ever-growing legion of devotees enthralled by the band's imaginative and uniquely affecting blend of music, magic, storytelling, and games that collapses the boundaries between pop experimentation, theater, and performance art. Mary's Voice, The Music Tapes' third full-length album, is the warmest and most accessible invitation yet into Koster's world-the culmination of a vision he has been realizing for over a decade.

That vision began taking shape in the '90s, during which time Koster also became a key member of Neutral Milk Hotel and a contributor to The Olivia Tremor Control and other legendary members of the enormously influential Elephant 6 Collective. Since then, Koster (along with long-time creative collaborator Robbie Cucchiaro on horns) has pushed the boundaries of what audiences have come to expect from an "indie rock" band-performing alongside mechanical contraptions like the 7-Foot-Tall Metronome, displaying virtuosity on both the singing saw and orchestral banjo, and staging unique caroling and lullaby tours.

Those trips have taken Koster into over 500 homes across the United States and Canda and the spirit of them infuses Mary's Voice. "The magic was in the people who would welcome us into each house," said Koster. "We would literally go from a huge mansion on a hill overlooking the Hollywood sign, to squats with a bunch of punk kids who'd made a geodesic dome covered in moldy carpet for us to do the show in and forgot to make a hole big enough for the equipment to fit in through. We played for children of all ages-from teenagers to great-grandparents. We would visit the first house at nightfall and the last sometimes not until dawn. The fun and the warmth of each stop-how absolutely unique each was while still being so deeply familiar-was amazing and taught me how much like dreaming living can be."

Mary's Voice, the follow up to 2008's acclaimed Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes, is part one of a planned two-part album and inaugurates a newly active phase in The Music Tapes' evolution-with plans to tour the world in a circus tent later this year and an NPR radio serial in the works. It was recorded with The Music Tapes' signature method of using recording machines of both past (early 1900s, '30s, '40s, '60s) and present to achieve a timeless sound. In Koster's own words: "I love sentimental melodies that you can hum with feeling. People warn against sentimentalizing or mythologizing the past. It's any failure to mythologize the present that I think we have to be afraid of. This is a miracle. You are a miracle. Our lives are magic, and our times all the more so. Music proves it." - www.mergerecords.com/

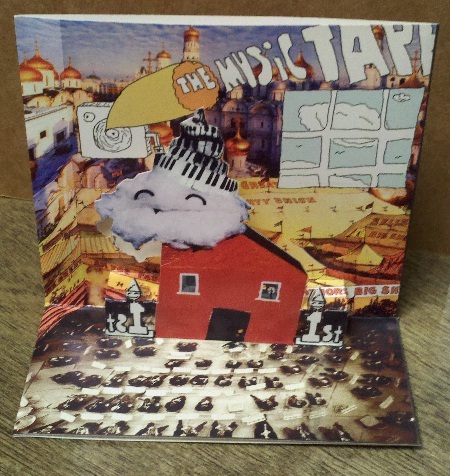

Stepping out of a storybook, the ageless, elfin Julian Koster is a

music industry oddity. A member of several notable Elephant 6 groups,

including Neutral Milk Hotel, he embodies the boisterous, endearingly

childish side of the musical collective. With The Music Tapes, he’s

become a defender of folk traditions, placing emphasis on intimate

community-oriented performances, especially caroling (the artwork’s

Rankin/Bass-looking figurine is yet another example of his fixation on

Christmas). News that the band plans to travel and perform with a circus

tent is unsurprising when we remember this is the guy who toured with a

seven-foot metronome and personified his musical saw by naming it

Badger, even giving it a gender (female) and age (she should be around

12 now, I think).

Situating Mary’s Voice among The Music Tapes’ Imaginary Symphonies series is a little tricky. 2nd Imaginary Symphony for Cloudmaking, an hour-long narrative unbroken into separate tracks (more audiobook than album), was released in 2002, three years after First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad; Mary’s Voice is rumored to be the first segment of a potential two-part 3rd Imaginary Symphony. There is a narrative being told here that’s thankfully less obtrusive and cloying than Cloudmaking’s, but hearing the eventual second half isn’t essential to appreciate Mary’s Voice, which stands alone as an extended lullaby that soothes even as it piles chaotic noises atop one another. After a release dwelling on the sea and a couple dedicated to clouds, it’s on to sleep and dreams in what’s intended to be their warmest and most accessible record.

But for all its supposed warmth, there’s something sadder about the night-themed Mary’s Voice than The Music Tapes’ most recent album, 2008’s exuberant Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes. It might be all the references to darkness, within lyrics and titles, that began with last year’s Purim’s Shadows EP, or maybe it’s the fragility of Koster’s voice on tracks like “The Big Beautiful Shops” and “Spare the Dark Streets.” From him, we’re used to a playful scratchiness, a refusal to play nice and pretty up the quality of sound or rasp of voice that divide so many listeners. Although Mary’s Voice maintains the anachronistic recording techniques that give The Music Tapes’ sound a characteristic hiss, Koster’s wail is sometimes subdued into little more than a whisper; even when he’s belting out impassioned lingering syllables from deep in the gut with Mangum-like intensity, his voice is a little softer, a little more considerate than on For Clouds and Tornadoes, where he valiantly sought nearly-impossible-to-hit notes (and sometimes connected).

And then there’s the otherworldly waver of the poor man’s theremin, the musical saw. Used as a quirky contrivance in things like Jeunet’s Delicatessen, the saw — as well as the implementation of found objects as instruments — now threatens to connote an almost artificial, try-hardish whimsy. To Koster’s credit, his selection of instruments — as potentially gimmicky as they might appear — never comes across as forced. For The Music Tapes, the combinations simply work to achieve their goals: the saw pairs well with the calliope (of roaming 19th-century fairs) to establish a dreamy, ethereal atmosphere that sets the tone for the entire album. Even if the 3rd Imaginary Symphony never materializes, the contemplative Mary’s Voice may win over listeners who couldn’t stomach the unrefined energy of The Music Tapes’ older work, with artistic integrity intact. - Ben Rag

Situating Mary’s Voice among The Music Tapes’ Imaginary Symphonies series is a little tricky. 2nd Imaginary Symphony for Cloudmaking, an hour-long narrative unbroken into separate tracks (more audiobook than album), was released in 2002, three years after First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad; Mary’s Voice is rumored to be the first segment of a potential two-part 3rd Imaginary Symphony. There is a narrative being told here that’s thankfully less obtrusive and cloying than Cloudmaking’s, but hearing the eventual second half isn’t essential to appreciate Mary’s Voice, which stands alone as an extended lullaby that soothes even as it piles chaotic noises atop one another. After a release dwelling on the sea and a couple dedicated to clouds, it’s on to sleep and dreams in what’s intended to be their warmest and most accessible record.

But for all its supposed warmth, there’s something sadder about the night-themed Mary’s Voice than The Music Tapes’ most recent album, 2008’s exuberant Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes. It might be all the references to darkness, within lyrics and titles, that began with last year’s Purim’s Shadows EP, or maybe it’s the fragility of Koster’s voice on tracks like “The Big Beautiful Shops” and “Spare the Dark Streets.” From him, we’re used to a playful scratchiness, a refusal to play nice and pretty up the quality of sound or rasp of voice that divide so many listeners. Although Mary’s Voice maintains the anachronistic recording techniques that give The Music Tapes’ sound a characteristic hiss, Koster’s wail is sometimes subdued into little more than a whisper; even when he’s belting out impassioned lingering syllables from deep in the gut with Mangum-like intensity, his voice is a little softer, a little more considerate than on For Clouds and Tornadoes, where he valiantly sought nearly-impossible-to-hit notes (and sometimes connected).

And then there’s the otherworldly waver of the poor man’s theremin, the musical saw. Used as a quirky contrivance in things like Jeunet’s Delicatessen, the saw — as well as the implementation of found objects as instruments — now threatens to connote an almost artificial, try-hardish whimsy. To Koster’s credit, his selection of instruments — as potentially gimmicky as they might appear — never comes across as forced. For The Music Tapes, the combinations simply work to achieve their goals: the saw pairs well with the calliope (of roaming 19th-century fairs) to establish a dreamy, ethereal atmosphere that sets the tone for the entire album. Even if the 3rd Imaginary Symphony never materializes, the contemplative Mary’s Voice may win over listeners who couldn’t stomach the unrefined energy of The Music Tapes’ older work, with artistic integrity intact. - Ben Rag

The Music Tapes have become purveyors of a particularly mournful strain of old-movie-soundtrack pop over the past few decades, although that’s hardly the extent of their bag of tricks. Mary’s Voice, the latest effort from this 90’s-era collective spearheaded by former Neutral Milk Hotel member Julian Koster, mostly fits that description. It’s the aural equivalent of a dusty old attic, rife with sounds that evoke memories of earlier times.

Mary is a patchwork of Koster’s melancholy banjo strumming, with some musical saw-playing and baritone horn thrown in for good measure. It’s not always easy to listen to—it sometimes seems as though Koster is singing to himself, and the rest of us are having the awkward experience of catching sight of him in his bedroom with the door half-open. It frequently sounds as though it’s being sung in his own secret language, making it hard for the listener to glean his secrets. This often seems to be an album made for Koster’s own benefit, and that can be a hard layer to penetrate.

One example of this is “The Big Beautiful Shops (It’s Said That It Could Be Anyone)”, which has a dirge-like quality that showcases Koster’s voice in a low, despairing wail. Driven by synths and an orchestral crash cymbal clamor, it’s unrelenting bleakness makes it a difficult listen. “To All Who Say Goodnight,” underscored by church bells and the ever-present banjo, Koster’s voice is once again the defining feature–at least until the pace picks up and the drums kick in. It’s still hard to tell what he’s so sad about, but it sounds as though it was a real bummer.

The album reaches a much-needed crescendo in “Takeshi and Elijah,” the final track. The backbone comes from what sounds like a sample of a symphony orchestra, and it supplements Koster’s tortured wail perfectly. While the rest of the album can be dangerously low-key, “Takeshi and Elijah’s” relative bombast makes you wish that the rest of the album could maintain the same level of energy and craftsmanship.

So who is Mary, and what is it about her voice that is so compelling? This is an interesting question to search for an answer to while combing through the esoteric morass of Mary’s Voice. You may not ever find one, but it’s a mystery (mostly) worth taking the time to unravel. - Katherine Flynn

Following the tragic loss of Olivia Tremor Control mainman and Elephant 6 Holiday Surprise mainstay Bill Doss earlier this year it would be easy, especially in light of Jeff Mangum’s seeming return to the hinterlands following a brief return to the public eye, to consider Elephant 6, those beatific kids huddled in a commune in Athens, Georgia who went on to make some of the greatest records of the ’90s and early ]00s, a spent force.

That statement, in light of the potential shown on The Music Tapes‘ 2008 album For Clouds and Orchestra and the promise held in their astounding performance at this year’s Mangum curated ATP festival, would seem to be a premature assessment. This record, a wonderful early Christmas present of an album, should set the idea entirely to rest.

Julian Koster has created the most musically clearheaded, touching, connective and accessible of his works to date in Mary’s Voice, drawing on his years of musical collage experimentation (he’s been creating wildly experimental mixtapes since the age of 16) and marrying it like puzzle pieces to his parallel time in more “straightforward” bands like Neutral Milk Hotel and the aforementioned Olivia Tremor Control.

While Koster’s previous solo work, however beautiful, was an ethereal, often fleeting experience, he has managed here to solidify those ideas he’s hinted at before into an entirely more satisfying, memorable and entirely welcoming whole. This is not to say that Koster’s work is no longer half-alien, part-stargaze, part-intangible: he’s simply tamed the wildness of his own imagination enough to deliver an absolutely excellent pop record.

A buzzing bass and a nonsense lyric imbued with hope (“S’alive to be known/For so long here” he repeats) and intuitive and simple melody first hint at greatness on ‘S’Alive (Pt1)’ while on the following track ‘The Big Beautiful Shops (It’s Said That It Could Be Anyone)’ you get the first hint that you may be listening to something miraculous. Koster’s Thom Yorke-like wail sails across the juddering, rolling instrumentation, heart filled with unbridled joy and unbearable sadness. The song’s dynamics are so emotionally intuitive as they switch from cut ‘n’ paste electronica to organic, full-bodied (does this sound like a cider?) orchestra as to involuntarily drop the jaw. It shares the build and fall of most post rock but also boasts the instant connection of classic pop – moving wherever it wants and warmly carrying you along under its glowing orange wing.

That memorable wail of Koster’s is reaffirmed on ‘To All Who Say Goodnight’, a Jeff Tweedy strum transposed to banjo that then whirls into carnival song. The chorus and juxtaposition of ancient and baffling sounds suggest a Radiohead of the heart and the soil as opposed to one of the technological and alienated.

The timelessness of the record is the thing though. It sounds like a relic brought to life, like modernity sent into a sepia past, like a potential future tinted with strong wine and weak wills. ‘The Dark Is Singing Songs (Sleepy Time Down South)’ sees the musical saw, organ, brass and Koster’s untrained croon combine to soar into a blue sky-bound sound of antique wonderment. His yearning notes, the trill of the saw and the circus crash of drums fall together to create something defiantly melodic, an alternate universe lesson in musical history.

There’s more time travel on ‘Spare the Dark Streets’ as a tear-pricking violin line draws us in to the sound of a Victorian nickelodeon show, or perhaps the soundtrack to a forgotten 1920s cartoon. If you’re not a bit in love by the time Koster’s clashing voice smiles “Summer steam filled all your eyes” then, in the time honoured fashion, please check for a pulse.

The wonder continues with both ‘Kolyada’, a 1930s whistle of a tune that could have soundtracked a Jimmy Stewart classic, and ‘Go Home Again’, a serrating lament and duet for voice and organ. A torch song for the drunk, the drugged or the just plain sleepy it combines, as much of the album does, a childlike naivety and purity with hints of the shadows of darkness that fill the adult world. While Koster never allows one to overwhelm the other this is, perhaps, the saddest he’s ever sounded on record. With a melody reminiscent of ‘We’ll Meet Again’ and closing on the chime of distant bells you’ll be hard pressed to control your emotions as this plays out.

There’s more, though, there’s more. For Neutral Milk Hotel fans there’s a rollicking Mangum-like jam that teases climaxes, juts out rhythms, tickles you with banjo and barrages you with crashing, pounding waterfalls of drum – there’s even a tense/lovely middle eight build on the repeated phrase “We’re waiting” before we’re allowed the joyous return to explosive orchestra sounds.

Then there’s the album’s truly triumphal moment, ‘S’Alive To Be Known (May We Starve)’ which brings back the coda of ‘S’Alive’ with more dramatic instrumentation and more forceful intent. It’s the sound of a rag tag, resuscitated Civil War army band brought back to life by Koster’s sweeping musical imagination. You’ll need to be seated for this one, should you simply collapse in awe.

Finally we’ve ‘Takeshi and Elijah’, lyrically the clearest offering here with Koster’s voice prominent (though the exact story he’s telling is veiled in obscure imagery and juxtaposed situations). Lines like “Did you scare them dressed in sheets of white/At dizzying heights” dance alongside more painful words, almost impossible to not offer emotional weight to in light of the recent death of their close friend Doss, like “Pointing hands, pointing hands/Ghosts of the old friends we all used to be”, the alternate close to that couplet being “Somehow we all played in musical bands that toured throughout the land… tell them the secret to snowing”.

When, after nearly 5 and a half minutes The Music Tapes’ full orchestra hits its cataclysmic stride your arms reach into the air and you are momentarily there with the Elephant 6 Collective, preserved in musical aspic.

A love letter to musical forms that pre-date rock ‘n’ roll, a heartfelt reminiscence of a key moment in modern music’s trajectory, a beauteous and tender embrace of melody, invention, love and strangeness, this is a magnificent, near-magical album that should prove conclusively to anyone who cares that Julian Koster and his Music Tapes are just the right guys to take the Elephant 6 dream of a musical utopia through to its logical, illogical, frightening, chest-bursting conclusion.

It’s something of a masterpiece, you see.- Michael James Hall

Pick up any Elephant 6 record worth a damn, and chances are you'll find Music Tapes frontman Julian Koster's name somewhere in the liner notes. For going on 20 years, Koster's been instrumental in shaping the sound of Elephant 6's sprawling psychedelia, lending his singing saw (and his considerable compositional expertise) to Neutral Milk Hotel and the Olivia Tremor Control, to his own Chocolate USA and the Music Tapes. Though the weird whinny of Koster's favored axe and his symphony-on-a-shoestring arrangements are nearly as essential to the E6 sound as their thousand-part harmonies, his work as the Music Tapes has occasionally struggled to distinguish itself from the company he keeps. The group-- Koster, multi-instrumentalist Robbie Cucchiaro, and a rotating cast of E6 regulars-- debuted in 1999 with the maddeningly scattershot 1st Imaginary Symphony for Nomad, a particularly dizzying spin on the Elephant 6 house style. Their second official release, 2008's Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes, settled out out some of the earlier stuff's more addled arrangements, drawing on Koster's love of American pastorals. Good as Clouds and Tornadoes was, though, Koster's never quite set himself apart as a songwriter the way some of his good friends and contemporaries have. Unless you're ankle-deep in E6, you probably best know Koster as a utility man, a bit player, "the dude with the singing saw."

Running an impressive gamut between stark confessionals and sepia-toned Stephen Foster fantasia, the new Mary's Voice

is a grand, genre-straddling vision in sound; on strictly musical

terms, it's the most accomplished Music Tapes LP to date. Woozy opener

"The Dark Is Singing Songs (Sleepy Time Down South)" is a Disneyfied

lullaby dirge that seems to arrive about a century past its born-on

date. The fairly self-explanatory "Saw and Calliope Organ on Wire"

follows, an instrumental piece that sounds like the way a yellowed photo

of Coney Island looks. This time-travel effect is slightly unsettling,

like a letter to your grandmother-- or, perhaps, the postcard that inspired your favorite record cover-- falling out of an old book. Mary's Voice

is interspersed with church bells, ambient whatsits, otherworldly saw

interludes, even a brief intermission. Koster's knack for putting sounds

together certainly hasn't gone uncommented upon over the years, but

here, he's not simply stringing together a few dozen parts. In Mary's Voice's, he and Cucchiaro have created a eerily beautiful little world unto itself.

This being an Elephant 6 record, Koster cuts the instrumental rigamarole with a smattering of proper songs along the folk-psych continuum. These tunes are sharply composed, if a bit slippery on subject matter; there's a whole backstory to Mary's Voice, with Mary, something about whales, and the melody of "Playing 'Evening'", but how much any of that actually matters seems to be left up to the listener. Koster's voice isn't what you'd call classically beautiful, but it's sweet, and expressive, and possessed with a solemn optimism that-- when coupled with his fondness for the pump organ-- draws to mind everybody from Daniel Johnston to Phil Elverum. Still, it's Koster's old friend and bandmate Jeff Mangum himself who looms largest over Koster's songwriting this time around. Though Mangum's actual role in Mary's Voice is tough to locate-- he's credited with both "turntable manipulation" and "chair," which, well-- there's more than a bit of him in the urgent strums and vocal up-and-over of "Playing 'Evening'" and "To All Who Say Goodnight" and especially closer "Takeshi and Elijah".

Koster's got as much right to claim a Mangum influence as anybody, but here on Mary's Voice, he doesn't so much borrow from Mangum as channel him. You could easily take the stark, deeply felt "Takeshi" as a spiritual cousin of sorts to Aeroplane's astonishing finale, "Two Headed Boy Pt. 2.": Koster, addressing a seldom-seen friend, talks up their "musical bands that toured through the land," and it hardly even seems a stretch to think the "sweet, snowy tune" is Mangum's semen-stained "Communist Daughter". "Takeshi" is a song of encouragement, acknowledging the past while casting an optimistic eye toward the future. It's not hard to read as a sort of state of the union address for Elephant 6 that feels particularly poignant in the wake of Mangum's recent return to the road and this summer's passing of the Olivia Tremor Control's Bill Doss.

This time out, the songs themselves are less restless, less prone to distracting themselves, but there are enough hard turns and fidelity shifts between the peculiar orchestrations and Koster's somewhat strangled vocals on the stripped-back songs that the effect can be a bit decentering. Even with the strides he's made as a songwriter in the few years since Clouds and Tornadoes, the more ornately composed stuff here is, "Takeshi" aside, more distinctive than the songs themselves. Still, this is an album's album: prismatic, ornate, never wanting for ambition. A song or two here and there might falter a bit, but taken as a whole, Mary's Voice is a minor triumph.

After years of quietly rooting for the guy, I went into Mary's Voice hoping Koster would use the record to find his own. I realize now I'd been looking in the wrong places. Koster plays well with others; that much we've known all along. And he, more than most, has always seemed particularly attuned to the collective goals of E6; this is, after all, the guy who sold his banjo from the Aeroplane sessions so he and his buddies could go on tour. So if the best moments on Mary's Voice find him surrounded by-- and occasionally channeling-- his old pals, well, that's almost to be expected. Koster's always been quite good at making himself heard, he just happens to be at his loudest when joined in chorus-- real or imaginary-- with his old friends, to lend his talents to something bigger, more communal. You won't find that little logo anywhere on the record, but the detour-prone, profoundly odd, unstuck in time Mary's Voice is an Elephant 6 record through and through. Koster, with a little help from his friends, made this one worth a damn. - Paul Thompson

This being an Elephant 6 record, Koster cuts the instrumental rigamarole with a smattering of proper songs along the folk-psych continuum. These tunes are sharply composed, if a bit slippery on subject matter; there's a whole backstory to Mary's Voice, with Mary, something about whales, and the melody of "Playing 'Evening'", but how much any of that actually matters seems to be left up to the listener. Koster's voice isn't what you'd call classically beautiful, but it's sweet, and expressive, and possessed with a solemn optimism that-- when coupled with his fondness for the pump organ-- draws to mind everybody from Daniel Johnston to Phil Elverum. Still, it's Koster's old friend and bandmate Jeff Mangum himself who looms largest over Koster's songwriting this time around. Though Mangum's actual role in Mary's Voice is tough to locate-- he's credited with both "turntable manipulation" and "chair," which, well-- there's more than a bit of him in the urgent strums and vocal up-and-over of "Playing 'Evening'" and "To All Who Say Goodnight" and especially closer "Takeshi and Elijah".

Koster's got as much right to claim a Mangum influence as anybody, but here on Mary's Voice, he doesn't so much borrow from Mangum as channel him. You could easily take the stark, deeply felt "Takeshi" as a spiritual cousin of sorts to Aeroplane's astonishing finale, "Two Headed Boy Pt. 2.": Koster, addressing a seldom-seen friend, talks up their "musical bands that toured through the land," and it hardly even seems a stretch to think the "sweet, snowy tune" is Mangum's semen-stained "Communist Daughter". "Takeshi" is a song of encouragement, acknowledging the past while casting an optimistic eye toward the future. It's not hard to read as a sort of state of the union address for Elephant 6 that feels particularly poignant in the wake of Mangum's recent return to the road and this summer's passing of the Olivia Tremor Control's Bill Doss.

This time out, the songs themselves are less restless, less prone to distracting themselves, but there are enough hard turns and fidelity shifts between the peculiar orchestrations and Koster's somewhat strangled vocals on the stripped-back songs that the effect can be a bit decentering. Even with the strides he's made as a songwriter in the few years since Clouds and Tornadoes, the more ornately composed stuff here is, "Takeshi" aside, more distinctive than the songs themselves. Still, this is an album's album: prismatic, ornate, never wanting for ambition. A song or two here and there might falter a bit, but taken as a whole, Mary's Voice is a minor triumph.

After years of quietly rooting for the guy, I went into Mary's Voice hoping Koster would use the record to find his own. I realize now I'd been looking in the wrong places. Koster plays well with others; that much we've known all along. And he, more than most, has always seemed particularly attuned to the collective goals of E6; this is, after all, the guy who sold his banjo from the Aeroplane sessions so he and his buddies could go on tour. So if the best moments on Mary's Voice find him surrounded by-- and occasionally channeling-- his old pals, well, that's almost to be expected. Koster's always been quite good at making himself heard, he just happens to be at his loudest when joined in chorus-- real or imaginary-- with his old friends, to lend his talents to something bigger, more communal. You won't find that little logo anywhere on the record, but the detour-prone, profoundly odd, unstuck in time Mary's Voice is an Elephant 6 record through and through. Koster, with a little help from his friends, made this one worth a damn. - Paul Thompson

Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes (2008)

Streaming ovdje

It's interesting then that, in the nine years since its release, The Music Tapes' popularity has only experienced growth, garnering a rabid fanbase that borders on the cultish. Perhaps it was because Koster wasn't as much on the fringe of the E6 collective as in the heart of its experimental aspirations. He was right alongside Jeff Mangum petitioning for more distortion and more noise on In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, while his masterful strokes in The Elephant Six Orchestra and particularly Major Organ & The Adding Machine (that oh-so-mysterious experimental pop/musique concrete configuration) were slopped on with a brush drenched in beards of tape-collage alchemy and psychedelic snouts, sounds that have increasingly come to articulate the more bizarre dimensions of Elephant Six.

Similarly weird are his live sets, which feature his own musical inventions -- The 7 Foot Tall Metronome, Orbiting Human Circus Tapdancing Machine, The Clapping Hands Machine, etc. -- playing with him onstage. During "Freeing Song by Reindeer," for example, Koster balances what looks like a keyboard/jack-in-the-box hybrid on top of his head and cranks its handle counter-clockwise, which causes two cartoonish "hands" to repeatedly plop on the keys. Meanwhile, the adorable Static The Television takes lead vocals on "An Orchestration's Overture," as its inventor aggressively strums the banjo as if it were an electric guitar. Most recently, The Music Tapes played Athens Popfest 2008, in which he had some 300 people join him in a kazoo parade after his set to a nearby field, where everyone was blindfolded and ran around the dark chasing someone with a bell.

Indeed, the primary difference between these experiments and those of, say, noise and drone practitioners is that Koster's ultimate aim is inclusiveness. This isn't about "authenticity" or some silly "forward-thinking" construct. It's about indulging in escapism without assuming that diversion is inherently negative, or that transparency is undesirable, or that critiques of hyperreality are not without their own irony. It's about having faith in fantasy. His music is an invite to an alternate reality, one that is as unique as it is charming. Perhaps the most appropriate example are his "secret" outdoor shows — sort of like a Fluxus happening — for which he posts cryptic messages on his website revealing the location, date, time, and instructions. Those fortunate enough to make it to these one-off gigs are asked to keep details vague, perhaps to preserve the sanctity of the moment (or for reasons only the participants will ever know). All I could find out is that one of the events featured paper sailor hats, acorns, and a singing saw.

Thankfully, Koster's singular swipes persist throughout the highly anticipated follow-up, Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes. It's not surprising, because many of these songs date back to before 2000, with some appearing on 2002's 2nd Imaginary Symphony For Cloudmaking (a 65-minute story album with artist Brian Dewan about a boy named "Nigh," presumably after Jeff Nigh Mangum). The new album doesn't reach the overt weirdness of its predecessor or Major Organ, but like those albums and In the Aeroplane, it revels in a soundworld that's entirely its own. Captured with a vast array of equipment (1930s Webster Chicago wire recorder, 1930s RCA ribbon microphone, 1960s Ampex 4-track, Hi-8 video camera, Dictaphone, computer, etc.), the album seems to intentionally project its colorful instrumentation in black and white, forcing listeners to confront their relationship with sound quality and how it might influence their tastes. Indeed, while the production suffocates the album's massive emotional and dynamic scope, sound quality pushed to these limits becomes something else entirely. Similar to a Daniel Johnston cassette or a Joe Tex 7-inch, the quality itself becomes aestheticized, like its own instrument.

Present again are the singing saw and bowed banjo, Koster requisites, sparingly embellished with everything from accordion, piano, tape organ, and drums to the euphonium, trumpet, flugelhorn, clarinet, and strings. In addition to Robby Cucchiaro and Eric Harris (who have contributed greatly to The Music Tapes in the past), the music is fleshed out by E6 regulars like Jeremy Barnes and Scott Spillane of Neutral Milk Hotel, Laura Carter of Elf Power, Will Cullen Hart of The Olivia Tremor Control/Circulatory System, and Kevin Barnes from of Montreal. Inventions like The 7 Foot Tall Metronome, the Singing Saw Choir, and The Clapping Hands help too. Yet nothing sounds cluttered. In fact, departing slightly from the sometimes spastic, collage approach of First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad, tracks like "Freeing Song for Reindeer," "Manifest Destiny," and "Tornado Longing for Freedom" allow for Koster's bare, nakedly sublime expressionism to take the forefront.

With lyrics like "Never before did we worry about you/ Now we are sure that there is cause for alarm" ("Freeing Song for Reindeer") and "Tornado cries, ‘Run for your lives!’ My tired wind's lonely and longing for freedom from storming" ("Tornado Longing for Freedom"), the album could be described as ominous if it weren't for the heartfelt delivery. There's also a lingering despair to the lyrics, but it's delivered with flashes of unabashed lyrical humanism and optimism. "‘Sail,’ said the seas/ The wind never sins/ Where its circumference on axis spins… How in the world can you say the world is a sad place?" he pleads on "The Minister of Longitude." Koster celebrates contentedness and rumination as much as he conjures longing and search, with most of the lyrics dealing with nature, as if its manifestations were actually sentient (and therefore held accountable for their actions), as if his strident yearnings could possibly synthesize the album's nature/non-nature dialectic.

Elsewhere, Koster resurrects the commanding, dominating vocal performance of Mangum on "Manifest Destiny," singing, "And you're mother/ And you're father/ And you're sister/ And you are bro — ther!!" Here he stretches his vocal chords so thin you imagine them as rubber bands, flinging off into infinity, dimpling the spacetime continuum. His head is obviously pointed skyward on "Saw Ping Pong And Orchestra," shouting "Nimbus, stratus, cirrus!!" with such urgency that you'd swear the opening ping pong ball samples had coalesced into a brilliant celestial sphere. In fact, melodies are so elongated, so disjointed that their forms reflect the occasional surrealism of his lyrics ("Ride the elves' cloven hoofed horsey, and find there's a symphony dreaming of you"). Heavy breaths are taken just to finish lines, choruses start early, verses are lopsided; everything sounds in perpetual transition, yet it all feels complete. And the subtlety! When the horns and strings come and go on "Songs for Oceans Falling," all I can envision is a warm, pulsating glow, dissipating with the kind of modest send-off one would expect from such tasteful employment.

Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes isn't your typical album. Not only is it an idiosyncratic release for Merge, but it's an anomaly for independent music. What the album emphasizes is its own mythology, one that simultaneously gives voice to the singing saw and the banjo, letting their sound colors join the more traditional rock instruments in a recontextualization process that not only retains faith in the romanticism of Western tonality, but also embraces it. In fact, The Music Tapes celebrate many of the illusions deconstructionists pierce holes through, yet that won't stop fans from paying over $125 for a CD-R copy of the long out-of-print 2nd Imaginary Symphony For Cloudmaking. Indeed, this album is an aesthetic expansion that is decidedly upfront and human, seeped in tradition, and with a vision that's seen all the way through -- it even comes with a make-your-own pop-up construction! With Koster's curious inventions, unprecedented happenings, risky production techniques, stylistic inventiveness, and lyrical dexterity, this album comes truly out of leftfield. For having now only released two official albums, this is quite an accomplishment. According to Koster:

I just find the imaginary more real than the physical. Magic, the way we find things beautiful, the light behind eyes, kindness, and how we want to serve and protect the things we care about — these things seem like the real foundation of the world to me. I hope that the songs on this record can be more than just postcards from a world, but an invitation to it, to anyone at all who may find such a place comforting and nice.Unless you're already a Music Tapes fan, chances are you haven't experienced anything quite as exquisitely raw, effortlessly transportive, and charmingly distinct in a long time. - Mr P

The 2nd Imaginary Symphony For Cloudmaking (2002) is a story album by The Music Tapes, consisting of the story of a boy named Nigh (seemingly named after Jeff Nigh Mangum), who lives with his blind grandmother.

The album also features instrumentation by Julian Koster to back the spoken word recording by Brian Dewan. It is yet to be mass released but has actually been finished and put through two self-released CD-R circulations, and played on WNYC's Spinning on Air. The last copy to sell on Ebay went for over $125. Julian has said that "an official release shall be arranged for, but it's not yet as, in truth, I've been too wrapped up in making new things."

Streaming ulomaka ovdje

First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad (1999)

Streaming ovdje

First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad album by Music Tapes was released Jul 06, 1999 on the Merge label. Few words can adequately prepare a listener for The Music Tapes' oddball FIRST IMAGINARY SYMPHONY FOR NOMAD. The album sounds as though a group of drug-bemused and slightly deranged elves went back in time and attempted to remake "Smiley Smile" on Thomas Edison's recording equipment First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad music CDs.

The Music Tapes is the mission of Julian Koster, the multi-instrumentalist (he lists musical saw as one of his instrumental proficiency) member of Neutral Milk Hotel First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad songs. Filled with brief but catchy songs and a host of strange sound fragments, this aggressively lo-fi disc is seamlessly segued together into a composite whole First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad album. But all is not weirdness for weirdness' sake--read the accompanying insert and you'll find this album's very human and melancholy heart First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad CD music.

Julian Koster's ubiquitous presence on a ton of well-regarded musical projects has led to his name being synonymous with "indie rock journeyman" in D.I.Y. musician circles. As an underground multi-instrumental creative force, Koster has few peers -- keyboards, banjo, singing saw...you name it, Koster has probably cut a track with it. Beginning in high school, Koster's musical trajectory was decidedly experimental and explorative. At age sixteen he issued his first "music tape," the sprawling Second Silly Putty Symphony, starting down a long and winding road of aural pastiche that would later develop into the often collaborative Music Tapes group. Alongside the infant-stage Music Tapes, Koster's proper high-school band, Chocolate U.S.A. (formed in 1989 and renamed after their original moniker, Miss America, brought on legal action from their televised namesake), took a more pop-oriented path, ultimately leading to the formation of the musician/friend collective known as Elephant 6. With two self-released Music Tapes 7" singles in the can (1997's Please Hear Mr. Flight Control and 1998's The Television Tells Us), Koster took up with Jeff Mangum, Scott Spillane, and Jeremy Barnes for the recording of Neutral Milk Hotel's groundbreaking second album, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea.

In 1999 the first formal Music Tapes release was issued (by Merge) -- an archaically recorded collection of spliced and manipulated tape experiments titled First Imaginary Symphony for Nomad. On board for the project were later Elephant 6 stalwarts Brian Dewan, Robert Carter, Olivia Tremor Control's Eric Harris and Will Cullen Hart, Neutral Milk Hotel's Jeff Mangum and Scott Spillane, and Of Montreal/Marshmallow Coast-er Andy Gonzales. European and U.S. tours ensued and, by the end of the decade, another Music Tapes project surfaced -- a split 7" picture disc that Koster shared with his flamenco guitarist father, Dennis. Into the 2000s, Koster kept busy with his Music Tapes-related projects, self-releasing the Brian Dewan-laden story album Second Imaginary Symphony for Cloudmaking and continuing a heavy tour schedule with various Elephant 6-related groups. In 2008, Koster collaborated again with his guitarist/father Dennis on a collection of Christmas carols, performed on the singing saw, titled The Singing Saw at Christmastime.- www.allmusic.com

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar