Sporo mičuće slike, nešto između fotografije i videa.

www.owenkydd.com/

Owen Kydd’s “durational photographs,” as he calls, them are in fact barely moving videos. Working in his studio, he composes still lives as static images, and after he records them their temporality is revealed only in subtle disruptions: a breeze catching gauzy materials, passing light, and so on. The longer we look, the more conscious we become of the fact that we are looking. Paradoxical tensions ensue, about the life of a thing, the value of images, and the beauty of the everyday. His latest piece is perhaps the most considered visual study of drywall tape ever.

How did you arrive at the parameters, and taxonomy, for “durational photographs”?

The Force of a Frame:

How did you arrive at the parameters, and taxonomy, for “durational photographs”?

I generally use two types of time, a shorter 30-40 second image, and permanent extension or loop. I found these only through the experience of looking for subjects that are nearly still. The most stable parameters are those of the picture itself and any historical antecedents, and then after that the control of the durational experiment where time is the only variable in the photograph.

You explicitly muddle the lines between photography and video in your work. However since you’re working with physical objects to compose still lives that inhabit specific framings, I could imagine sculpture, drawing, or even painting figuring into the way you craft the compositions you record. Typically what guides you in making a still life in the studio?

I am essentially a photographer because there is a camera between me and the subject, and I often use the lexicon of photographs. But after that I feel that I have the freedom to introduce elements from other mediums, including sculpture or even cinema. I think anytime someone is constructing something to be filmed, they encounter these ideas, even if it is a self-conscious mimicry. An artist that I think embodies this is Paul Outerbridge, he photographed meticulous sets that referenced different genres like Italian Metaphysical painting or Surrealism.

Are there any other artists you feel are especially meaningful precedents to what you do?

I think Andy Warhol or Michael Antonioni for example, or any artist that creates the feeling of something being photographed while still operating in duration. It’s a hard effect to describe, but when it occurs I think it says a lot about how we see time.

Are you trying to create an image in your mind, re-create something you’ve seen, exploit the qualities of certain materials you think will look neat on camera…?

I always try and reference situations I’ve witnessed, and sometimes I create an amalgam of those situations. I’m not concerned with the veracity of an object or event, and on that note I don’t think many camera artists have been since at least 1988 when Photoshop was introduced, or arguably ever. I’ve learned to look for certain materials that work well on video or at near-stillness, things like plastic or light reflections, or anything that synthesizes with the clear screen, liquid crystals, or refresh rate of the digital display.

Your videos are strikingly, almost startlingly, crisp and clear. Is there a point at which you could imagine them looking too lifelike? We are still at a point with technology where real life has a visual edge over the most sophisticated monitors and projectors. What I’m wondering is if your final destination resembles real life or some endless digital horizon which may hypothetically appear even realer?

You’ve put your finger on the mimetic irony in this process, that no matter how constructed something is, the technology has a way of giving it a tromp l’oeil effect. But I wonder if that is because the quality of the screens themselves or because we now see everything on screens, or both? In terms of a horizon of virtual reality, I think I have to stop somewhere I feel I have knowledge; I don’t imagine making Oculus rift artworks for example. Human vision evolved in a tension between two and three dimensions, and as such there is always intense pleasure in looking at the world as flat and imagining it round.

Do you feel limited being synonymous with such a consistent type of work? Do you see yourself bridging to anything else in the near future?

I don’t begin conceptually, meaning I don’t prioritize the idea of the work before the image; my concern instead is to use this system to make good pictures. So essentially it is an open field, as long as I feel I’m able to keep trying.

- www.crane.tv/owen-kyddThe Force of a Frame:

Owen Kydd's Durational Photographs

“it has the force of a frame to a picture.” *

–Edgar Allan Poe, The Philosophy of Composition

Owen Kydd makes videos that he calls “durational photographs.” What makes them seem like photographs is that the camera itself is fixed, focused on say, a store window or a black plastic bag. But they’re different from still photographs because they depict motion—sometimes very little (the reflection of the lights of passing cars in a window), sometimes quite a lot (the plastic bag blown by the wind). Because of the motion, Kydd himself says there is a sense in which they’re “cinema,” but since, as he also says, the screens make it possible to depict motion without the projection and the darkened room that turns even a gallery into a theatre, there’s also a sense in which they make possible a kind of refusal of cinema.1 It’s thus the photographic and the cinematic that provide the terms in which Kydd understands his work, and inasmuch as the videos are neither photographs nor movies, video functions for him less as a medium in itself than as a technology for addressing the relation between the photograph and the movie, for, more precisely, turning the cinematic into the photographic.

Thirty-five years ago (when Kydd was, like, two) it might have been tempting to describe this vexing the question of what medium he works in as an example of the postmodern critique of medium specificity, the “destruction,” in Rosalind Krauss’s words, of “the conditions of the aesthetic medium…”2 Today, however, it’s Krauss’s subsequent call for the “reinvention of the medium” that seems more relevant, since Kydd’s interest in the relation between the photograph and the cinema works more to complicate the specificity of the medium than to destroy it. But where the point for Krauss of the call to reinvent “the idea of the medium” has been to defend what she calls the “necessary plurality of the arts,” “a plural condition,” as she puts it, “that stands apart from any philosophically unified idea of Art” (305), it will, I want to argue, be hard to describe Kydd’s practice as appealing to the plurality of the medium against Art; on the contrary, it will be better understood as doing just the opposite, as redeploying the idea of the medium precisely on behalf of the idea of Art—and against a pluralism that is not only aesthetic but political.

We can begin to see how this works first by noting the distinction mobilized by Kydd between the materiality of these works and their aesthetic. The reason it makes sense to call them durational photographs, the reason why the medium to which they have a relation is the photograph, is first, as I’ve already noted, because the camera is fixed and, second, because the point of the fixed camera—the use to which it’s put—is the creation of a picture. And what determines the picture as a picture is the establishment of its frame, which will be essential not only to the unity of the work as a kind of photograph but to the very idea of art that Krauss deplores.

This absolute centrality of the frame is most immediately visible in a piece like Composition Warner Studio (on green) (even though the occasional violence of its movement makes it look less like a still photo than many of the others) precisely because the crucial (let’s say defining) moments in that piece – the ones that punctuate the passing of time, that insist on the photograph’s durationality—are the moments in which the edges of the bag are blown outside and then back inside the frame.

What a video (but not a still) camera can do, of course, is follow the motion, a capability that’s absolutely central to cinema (it’s partly this capability Kydd is insisting on when he suggests that technically his work is cinema) and that makes the question of the frame in moving pictures very different from what it is in the still. The moving camera subordinates the frame to the shot. What I mean here is just that it’s a crucial fact about cinema (to stick with Kydd’s term) not just that the camera can record motion but also that while recording motion it can itself move, and that this fundamentally alters (one might say, all things being equal, removes the pressure on) our sense of the frame. Whereas what Kydd insists on in Composition is just this pressure. Everything that happens in Composition happens in relation to the frame; the top and bottom of the bag moving closer to or farther away from the frame, the left side going out and then coming back in. So although one might imagine this transgression of the frame as functioning to weaken it, in fact, it functions to strengthen it. If what you wanted were really to weaken the frame you could just get rid of it altogether by following the motion of the bag with the camera. And this is what I mean by saying that the work seeks to function as a picture. It seeks to assert that what it is (what it is of) is determined by its frame. It’s not just that someone watching that bag blown about would not see what the beholder of the work sees (would not see it moving in and out of the frame); it’s that the event I just described—moving in and out of the frame—would not even be taking place. The function of the frame, in other words, is more ontological than epistemological; it doesn’t just determine what we can see, it determines what happens.

The force of this determination is even more visible in another more complicated work, the diptych, Marina and the Yucca. What makes it complicated is its relation to the portrait—to the problematic of the pose and to the psychological ambitions of the portrait. But, setting these aside for today, I want to stick with the question of the frame, and to do so by noting the difference between this video portrait and probably the most important video portraits of the last 25 years, the ones in which Thomas Struth asks his subjects to sit still for him for an hour and in which they struggle to do so. In the Struths, that struggle is at the center of the work, made especially vivid when, for example, Struth’s close friend, the brilliant classical guitarist Frank Bungarten, actually gets up and walks away in something like exasperation. By contrast, Marina seems barely to feel the pressure of posing. And in fact, she’s not under much pressure; where Struth’s subjects sit facing the camera for an hour, Marina is shown looking down, eyes shut or almost shut and only for two minutes. Of course, unlike the cactus, she feels what it means to be photographed and presumably if she had to sit for a full hour, the effect would be different but in her mere two minutes she seems almost to escape the problematic of the pose, to be more like the cactus than like Frank Bungarten. In this sense, at least, Kydd’s durational photographs are a lot less durational than Struth’s video portraits.

At the same time, however, because the work is shown in repeating loops, the passage of time is particularly or distinctively marked. Where in Struth, the passage of time for the subject of the video is identical to the passage of time for its beholder (if the video portraits were to run continuously, no one would be expected to sit through more than one showing), even in just a 7 minute 19 second showing, Marina and the Yucca repeats three times—which is to say the work is organized by the repeats, by an internal structuring of time not paralleled in the experience of the viewer. The effect is thus to separate the time of viewing from the time of performance, a separation that becomes all the more crucial if one takes seriously Kydd’s remark that ideally he’d like his videos to be playing continuously all the time and thus to “have a presence on the wall like that of a painting or photograph.”3 The difference between the still and the durational photograph remains, but here duration is placed under the sign of stillness—it’s made to happen as much as possible within the photograph rather than in the experience either of the subject or the beholder.

And this act of separation is reinforced by a relation to the frame different from but in its own way even more striking than that in Composition. Partly this emerges in relation to the other picture in the diptych, but what I want to focus on here is the movement (in context, an almost violent one) that everyone registers at the beginning of the second loop. What the beginning of the new loop makes visible is that Marina has been gradually and almost invisibly slumping just a little during the two minutes the camera has been on her, and it does so by restoring her to the position she was in at the start. Thematically, we might say, this is striking because it alters our experience of the relation between the still cactus and the almost equally still young woman. If she has seemed as untouched by the problematic of the pose as the cactus, it’s her difference from the cactus, the fact of her embodiment that’s now insisted upon. At the same time, however, there’s no sense of the work’s interest in her interiority. It’s the fact that she has a body, not her particular individuality, not what she is thinking or feeling, that is registered here. In this sense, the diptych seeks to foreground her personhood without in any way interesting itself in her personality, a gesture that has its own interest.

But, however we understand Marina’s movement downward, her movement upward is very different since, of course, she never does move upward. Rather, that movement is constituted entirely by the video, which here asserts its separation from—or, to use a more loaded aesthetic term, its autonomy from—its subject (it produces a motion that she does not) to complement what we’ve already described (in its internal structuring of the passage of time) as its autonomy from the viewer. What’s striking here is that a literal account of the medium specificity of the photograph (its indexicality, the Barthesian “that has been” of its relation to the event) is refused and replaced by a formal one (its frame, its determination of the represented event by the representation). And this is what I meant by saying earlier that in Kydd, something like what Krauss calls the reinvention of the medium is deployed on behalf of rather than as a critique of the idea of art. The commitment to producing an aesthetic of the photograph out of the material of the video—and thus to invigorating the concept of the frame—functions precisely to make the kind of general claim about art (“Art”) that Krauss deplores: to assert its autonomy.

Perhaps then we should be worried that Kydd’s work is the kind of art that George Baker (Krauss’s former student, and a little less sanguine than she is about the renewal of interest in medium specificity) warns us against when he worries that the “ breaking” of the “postmodernist and interdisciplinary taboo” against the medium “has let loose a series of… conservative appeals to medium-specificity, a return to traditional artistic objects and practices and discourses, that we must resist.”4

But it’s hard to see what’s conservative about this practice as art and, although a commitment to the autonomy of the work has sometimes been identified with a political conservatism, it’s even harder to see how that can be true today. In fact, it has been the challenge to the frame—what we might call the emergence of the postmodern more generally—that has functioned as the way artists do conservative politics in our period.

We can get a preliminary sense of what this means just by noting that the rise of the postmodern has been more or less coterminous with the rise of neoliberalism and with two sets of social and economic conditions. One is what the poet Maggie Nelson describes as the “triple liberations” of the Civil Rights movement, the women’s rights movement, and the gay rights movement.5 And although probably no one imagines that the equality for which these movements struggle has been achieved, probably also no one imagines that there hasn’t been significant change for the better. Just to take a very current and local example (the case is about to go before a judge here in Detroit6), today same sex marriage is legal in only 16 states (and Michigan is not yet one of them)—not so good. But at the time of Stonewall (1969) same-sex marriage was unthought of, and same-sex sex was illegal. In Michigan, until the Supreme Court’s decision in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), a sodomy conviction could be punished by fifteen years of imprisonment.

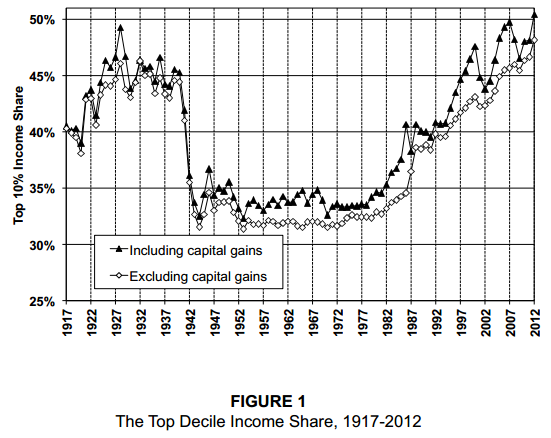

The other relevant change with respect to equality has been economic. But here, of course, the question is not how much better things are but, as the well-known graph below

suggests, how much worse. In fact, economic inequality in 2012 was not only much worse than it was in the late 60s and early 70s, it was worse than it’s ever been in American history. And the median household income in Detroit today is less than half what it was in 1970.7 If we were using Nancy Fraser’s terms, we could say (what Fraser says) that progress has been made with respect to questions of recognition but not with respect to redistribution. The way I myself would put it would be to say that progress has been made with respect to questions of discrimination but not with respect to the question of exploitation. Where inequality has taken the form of our seeing difference as inferiority (of racism or sexism or homophobia), we have fought it; where the difference actually is inferiority we have allowed it to flourish.

Obviously a lot could be said about these changes and about their relation to each other (and on this topic Fraser’s views and mine would be different, since I would argue that our current commitment to anti-discrimination functions to legitimate exploitation) but the relevant question here is only their relation to Owen Kydd’s durational photographs. Not, obviously to the subjects of these photographs—there’s nothing about that plastic bag that speaks to the question of women’s rights or Detroit’s bankruptcy. But instead to the question of the frame, which, I want to say, does.

How? If we just remind ourselves of what the critique of the medium and thus of the frame entails, we can see right away its alignment with Nelson’s three liberations and with the commitment to anti-discrimination more generally. For what the frame does is separate the work from its subject and thus at the same time from its audience, and what the critique of the frame does is refuse that separation and insist instead on the centrality of the beholder’s response. What we see, how we feel, become crucial components of the work and thus it’s possible for the normativizing gaze (white, male, straight/racist, sexist, homophobic) to become a crucial object of both aesthetic and social critique. After all, the problem of discrimination is in its essence nothing but a problem about how we see and respond—no racism without racists, no homophobia without homophobes. The appeal to the viewer produces the principle of neoliberal justice.

The frame, by contrast, makes everything outside the work and in particular our response to the work irrelevant. Defined by its internal relations (remember Marina’s little thrust upwards), the theory of itself that a work like Marina and the Yucca produces is of a structure that cannot be altered by our perception of it. And the image it offers is of a society organized not by the irreducible centrality of our subject positions but by their irrelevance, not by the conflicts between black and white, straight and gay, male and female and the problem of discrimination but by the conflict between labor and capital and the problem of exploitation. Every time the edge of that bag blows into and out of the frame, every time you experience your own irrelevance to the determination of what is and is not part of the work, you are offered the opportunity to understand what it means for it to be autonomous and for you to belong to a society structured by class.8

This is finally what’s at stake in Krauss’s identifying the return of the medium with a defense of the “plural condition”—of the “necessary plurality of the arts” as against a “philosophically unified idea of Art.” Pluralism is contemporary liberalism’s utopian ideal, a social field composed of identities demanding not to be discriminated against and cultures seeking to be acknowledged. The arts here, reinventing the differences between them by reclaiming their relation to the medium, are called upon to provide an emblem of that ideal, of difference as a mode of equality. But the medium in Kydd does not defend the plural; its use is just the opposite—to assert not only a philosophically unified idea of art but an idea of art as the form of philosophical unity. And in so doing, it makes visible a very different social structure, one that reconfigures difference as contradiction, understands inequality as its essence. What it produces may not quite be a class politics, but it is at least a class aesthetic.

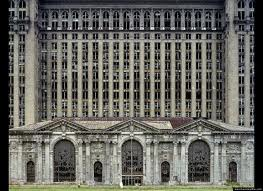

That’s why that plastic bag looks more like the city of Detroit today than do even the most beautiful pictures of its ruins.

Notes

* This essay was written as part of the run-up to the Mellon-sponsored nonsite/LACMA conference on photography that will take place in March 2015, and, in its final form, will further explore questions about the medium of photography and the question of portraiture in relation to Kydd, Struth and some of the major works (e.g. by Sander) in LACMA’s Vernon collection. This version, however, was originally presented as a talk at the ASAP conference in Detroit (October 2013) and I have, for reasons that are perhaps obvious, wanted to preserve the marks of that occasion.

1. Charlotte Cotton, Interview with Own Kydd http://www.aperture.org/blog/interview-with-owen-kydd/ April 2, 2013.↑

2. Rosalind E. Krauss, “Reinventing the Medium,” Critical Inquiry 25 (Winter 1999): 289-305; see page 290. The discussion of the critique of the medium is retrospective, as is photography’s identification in the ’60s and ’70s with a whole series of what Krauss calls “ontological cave-ins” (290), the critique of the author or artist, of the “original” and its “supposed unity,” etc. The call for the medium’s reinvention is correspondingly prospective but not, of course, a call for the reinvention also of the author, the original, etc.↑

4. George Baker, “Photography’s Expanded Field,” October 114 (Fall 2005): 120-140, see page 138. Perhaps a useful way of describing Kydd’s work here would be by antithesis to what Baker calls the “cinematic photograph” and its expression of what he calls the desire to “expand” photography’s “terms into a more fully cultural arena” (132). A piece like Composition seeks rather to render cinema photographic, and it’s by separating itself from the “cultural arena”—by insisting on its internal rather than its external relations—that it pursues what I will describe below as in effect a class aesthetic.↑

5. Maggie Nelson, Women, The New York School, and Other True Abstractions (University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, 2007), xxiii.↑

6. On October 16, the U.S. District Court Judge in Detroit set Feb. 25, 2014 as the date on which he would begin hearing testimony to determine whether there was a legitimate state interest in banning same-sex marriage.↑

7. The median household income in Detroit today is a little over $26,000, down (in 2010 dollars) from over $56,000 in 1970. http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2013/08/02/politics-counts-how-detroit-is-different/↑

8. For further discussions of the political meaning of autonomy today, see Jennifer Ashton, Poetry and the Price of Milk http://nonsite.org/article/poetry-and-the-price-of-milk; Nicholas Brown, The Work of Art in the Age of its Real Subsumption Under Capital http://nonsite.org/editorial/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-its-real-subsumption-under-capital. And one can find related discussions all over nonsite.org, especially in the contributions of Todd Cronan and in a text like Charles Palermo’s Miró’s Politics http://nonsite.org/feature/miros-politics. For some of my own contributions, see “The Politics of a Good Picture: Race, Class, and Form in Jeff Wall’s Mimic.” PMLA 125.1(2010): 177-184 and Neoliberal Aesthetics: Fried, Rancière and the Form of the Photograph http://nonsite.org/issue-1/neoliberal-aesthetics-fried-ranciere-and-the-form-of-the-photograph↑

Interview with Owen Kydd

Owen Kydd is a Los Angeles–based artist who has recently garnered attention for his “durational photographs,” video works that run four to six minutes and explore the interstitial space between still photography and cinema. Curator Charlotte Cotton discussed Kydd’s work in her article “Nine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles,” published in Aperture’s Spring 2013 issue. Here, Kydd speaks with Aperture about his work and its relation to still imagery, experimental cinema, and technology. The interview is one of a series of online-only texts commissioned to accompany the Spring 2013 issue, “Hello, Photography,” which examines the state of the medium in a time of great change. —The Editors

Aperture: How did you arrive at the concept of “durational photographs”?

Owen Kydd: I was thinking about the differences between cinematic moments with photographic qualities and static images with time added and decided that “durational” applied more to the latter. The idea of duration as “incomplete time” seemed to be a way of categorizing a flow of pictures without relying on models drawn from cinematic discourse. It was not a direct challenge to the definition of cinema—my work would likely fall into a strict definition of that category—but a way of proposing the possibility of undoing the time signature of the photograph. Whether a snapshot or a tableau, a photograph denotes the flow of time by its very lack of duration. It reveals the possibility of two types of time, one that is frozen and one that is always mobile. I am trying to reverse the typical effect of the still photograph, to ask people to think about creating stillness out of duration. It’s a performance of photography that I don’t think occurs so readily in the narrative activity of cinema.

AP: Photography’s evolution has always been determined by technology and your work reflects the fact that many cameras can now shoot both stills and video.

OK: That’s exactly it. I started making this work in 2006, when still cameras began to include decent video options. It seems so normal now, but I think when we look back at this development it will be seen not only as a democratization of filmmaking, but also as a considerable marker in the history of still images. In addition to these hybrid cameras, flat screens with resolution that made video look photographic became affordable. Before this people had to rely on projectors, which meant a darkened room, and, even in the gallery space, that’s cinema. It was really in about 2005 or 2006 that technology allowed duration to be a constant variable. I was hoping my project would retroactively define certain conditions of still photographs while actively reversing the absolute time of the photograph.

AP: Can you talk more about what you wanted to explore about “the conditions of still photographs”?

OK: I was looking for a set of “static” conditions that would make something look like it was in the middle of being photographed, even when in motion. That’s a difficult effect to categorize, and I decided that instead of directly trying to reproduce a set of photographic circumstances, I should start by confronting things that I found limiting in photography. I guessed that I might find this in the some of the clichés of the medium; for example, I started with straight or documentary photographs because they were problematic for me as still images. I wanted to know if adding time could allow me to avoid some classic presumptions associated with the documentary form yet still make good pictures. I was asking questions: if the subject of a photograph moves, can I say I’ve captured something decisive? And if not, can I create an image that continues to hold this type of charged moment?

AP: What was problematic to you about documentary images?

OK: It’s a big category and difficult to define, but I could say that certain photographs which claim to report the real have always had difficulties on some level. But luckily all photographs contain cells that eventually disrupt the certainties that were originally ascribed to them. I wondered if I could accelerate this process by changing the temporal status of the image enough to create a tension, or distance, between subject and viewer that would make us think about documenting in a more fluid form. The snapshot street image seemed like a good place to start because it is understood as the most instantaneous type of photograph.

AP: But many of your works are well-planned still lifes, not snapshots taken on the street. How does duration relate to the still life form?

OK: There were instances I felt like I was creating a camera-based “street” picture without a decisive moment, where I found a version of stillness that expressed an event. But there were other times when I felt duration trapped the subject in a succession of static moments that mimicked a more traditional search for the “essential” and did little to create the tension I was seeking. Ultimately though, I was learning about what made durational photographs work—different things that resisted the need to close the shutter just once. These were found in subtle temporal and atmospheric effects such as the movement of air and light, or materials and surfaces I was using—plastics, inorganic reflective surfaces, objects that had a trompe l’oeil or ambiguous appearance on the video screen. I brought back a collection of these elements to the studio to be assembled and filmed.

The most important thing for me, aside from the instrumental control that a studio offers, is the way it introduces a present tense. The studio erases temporal markers. I wanted to record the present-ness of the studio, possibly to ensure that there was even less chance of interning an event, but perhaps also to confuse the experience of viewing. I have been asked if my studio images are live feeds from another location, which I hope is a clue that something irregular is occurring.

AP: There is a sense of “crime scene” in some of the images—the atmosphere, the sense of oddity …

OK: I am both documenting and remaking storefronts from Los Angeles as a way of performing classic photographic subject matter; storefronts have been a consistent subject for wandering photographers like Atget, Walker Evans, or Lee Friedlander. I found window displays on Pico Boulevard that clearly hadn’t changed in years and that were lit all night, which is mostly when I filmed them, without pedestrians and only the traces of headlights in the glass. It wasn’t quite clear what many of the stores were selling—a florist selling party supplies and trophies, for example, and stores with the word “museum” in their name. Maybe it’s also the imagined history of L.A., but instead of Atget–like scenes, these locations took on a noir effect, meaning they still felt like the crime hadn’t been committed. A key to noir is the separation of subjects from the world around them through the contrast of light and dark, and this contrast helps create sense of distance in the picture, providing a tableaux effect.

Owen Kydd, installation view of Color Shift, 2013, Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

AP: In terms of the concentrated looking and observation involved in your durational photographs, I’m wondering about how experimental filmmakers—people such as Michael Snow, Peter Hutton, or Andy Warhol—have been a point of reference for you.

OK: I am in debt to expanded cinema and works like Empire, Wavelength, or James Benning’s films, and the last eight minutes of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’eclisse, for making moving images appear as if they contain still photographic moments. But with most of those films, the viewer is always located in the same space as the work; there is a projector behind you, and a beam of light that situates you physically within the process of forming the image on the wall in front of you. And I should make the point here that even if you are able to watch these films on an LED screen today, they were initially constructed for projection in a darkened room. I chose flatness as a parameter in my work, and am thus bound to a form of picturing. Fiona Tan’s monitor portraits and David Claerbout’s slide shows, even though they are mostly projected, operate in a similar field. Essentially, I think that if the photographic instant has been aligned with the conditions of modernist pictorial space, then its inverse performance should share similar concerns with surface, distance, and time. - www.aperture.org/

Owen Kydd‘s works are durational photographs made on video. Born in Calgary, Alberta in 1975, Kydd moved to Vancouver, Canada where he graduated from Simon Fraser University with a joint degree in Film and Fine Art. Over the past decade he has presented his work in numerous group exhibitions, including 2009’s “Sentimental Journey” at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Kydd currently lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Install of Knife (J.G.), 2011

© Owen Kydd

Lucas Blalock: Can you talk about the transition in your work from more episodic videos that produce a sort of serialized experience to the very tightly contained loops you have been making recently? I further wanted to ask a sort of goofy question about whether you think of these static, durational, looped pieces as still films or extended photographs?

Owen Kydd: I began by working with a duration of about 30 to 40 seconds per image. I found it was a good length to investigate still/motion, because it seemed enough to provide the manifest of a moment while also giving me the chance to create a montage. I made projects that would slide between a series of 9 or 10 of these images (with ellipses in between). Through this process of looking and editing I began to learn more about making pictures that responded to an extension, and I eventually felt like I could make some singular works.

One thing I found was that durational photographs worked better when they lost the indicators that tied them to a past, and began to confuse the moment of filming with the experience of viewing. Cinema or video works that have a long duration usually quote a recorded or lived time, and even in early pieces like Warhol’s Empire, which is close to losing its temporal markers, one is always made conscious of at least the possibility of an end point. This awareness could also be the tied to the projector’s flicker and the grain, but I also have found this condition in more recent video works. I am interested in trying to locate a more hallucinogenic or endless quality.

Still from Sighting, 2010

© Owen Kydd

In terms of the loop’s designation, I can say that when I think about making a still film, I think about changing a momentum and this feels decisive. But when I think about extending photography it suggests continuing a photograph’s inertia, and this seems more indefinite. My works are technically films because they rely on apparent motion, but the movement is limited within the frame, the effect is minimized, and often the same image is overlapped for many seconds without interruption. This process allows me to consider how a photograph can involve itself in motion.

LB: It is interesting to me that through this ambiguity between the still film and the “durational” photograph you end up bringing into question the boundaries of the device and even the strict usefulness of these categories. I feel that this is akin to the kind of interrogation that has prompted artists of late to return to the darkroom (amongst other strategies), but we are really discussing different limits here altogether.

OK: My pieces are exhibited on backlight screens or monitors. So, as with photography, there is a picture merged with a surface, albeit one that has a CFL light and a refresh rate. I feel that there is still an implicit tension between the screen and the subject. And because I am interested in making a picture of something in the world, I hope this tension presents something like the “possibility of reference” (to borrow Walter Benn Michael’s terms) rather than a fight against it. This is wrapped up in the forced distinction that the flatness of the photograph (and here, the screen) must make between itself and the exterior of the object it depicts, and this is a separation that I’m not sure fully exists in the projected image. I can also say that (with the monitor in mind) I find myself looking for specific surfaces.

Still from Yucca Color Shift, 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: Thinking now of the refresh rate, I am also beginning to feel two competing senses of time in these works – one that relates to the possibility of a totalizing photograph achieved through massive accumulation and the other a very slow, meditative temporality that fluidly elongates our looking.

OK: I think the temporal modes you are describing always appear together, although in different ratios, and probably stem from distinct types of photographs; the totalizing image probably begins with a snapshot while the more meditative likely comes from genre imagery. I made a picture of a carving knife in a store window that I think begins with the former. It has the found street ambience of an object that has been framed or chosen out of a passerby’s field of view, and in this sense it is a snapshot – a photograph that exemplifies an instant of lived time.

The Knife begins with this traditional correlation, where a frozen segment of time comes to denote its opposite – that is, fluidity. It adds back the perception of lived time, and this is mixed in with the occurrence of watching the video. In this sense I am trying to intensify the elongated sense of looking that is less pronounced in the imagined photograph of the knife, or the moment the head or camera turns to see it. It reenacts the moment the image was taken.

Still from Knife (J.G.), 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: Your description makes me think of Barthes and the melancholy that he associated with the temporal/photographic relationship. I am wondering if you could talk a little more about what you meant by “looking for specific surfaces”?

OK: You could say it’s a bit like adding-back-in Barthes’ lament, trying to apply duration but after the fact, and usually to an image that doesn’t contain a high degree of trauma in the first place. I’ve been concentrating on documentary or street images for this, somewhat to the chagrin of photographers in my life, because I find these images fit the performance better. I think the pictures I’m looking for also have something to do with that sense of inertia I was describing, not necessarily in terms of a compositional arrangement that draws the eye around the image, but more in terms of the things themselves, objects with a resistance to change. The monitor contains this same constancy, always on, or sleeping, it’s pixels perpetually repeating in the same place.

LB: There is something rather sci-fi about that and it is interesting to think about this stillness or constancy as a cultural metaphor of the digital age where the same binary code and pixel matrix underwrites an extraordinary breadth of information. Seeing the material of the “information super highway” as inert opens up some really unusual relationships to the inertias of the objects. For me these objects occupy a really tense environment. To stand still for some duration in the world, particularly without peripheral vision, as the space of your videos ask us to do, introduces a sense that something could “happen” at any moment. But for me it is not so much that I am waiting for something to take place in the video as much as I find myself bodily anxious as if the parameters of vision leave me both highly attenuated and at the same time vulnerable.

OK: That’s a great way to describe that sense of anxiousness. I think it stems from the fact that the snapshot image is made continually strange by duration, instead of being completed by it or reassured by it. When time is added, it is akin to an accumulation of snapshots all pointing to the flow of time, or the ‘before and after’ of the moment the knife was photographed. As a series it could appear as a bit of a paradox. But at 30 frames per second and 60hz, the accumulation masks the illogical nature of the sequence. The result is an unreal and impossible time and I think the ultimate effect of this is a more traditional ‘distancing’ between us and the picture, albeit a heightened separation.

Still from Canvas Leaves, Torso, and Lantern, 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: To end I’d like to ask about Canvas Leaves. This is a new work that uses the same presentation device to ponder a very different, highly contrived tableau.

OK: Canvas Leaves is intended to reverse the distancing process. It is a studio-set with a window box chiaroscuro made as a compendium of several storefronts on Pico Boulevard. Everything in the arrangement is plastic or artificial and even though it is static, I tried to make its arrangement unpredictable. The white canvas leaves hanging upside down, rotate left and right with the flow of air in the room (I had to rent an air-conditioner because it was a really warm August).

I hope in a way this piece takes a type of still-life that concerns the effect of time across objects, and doubles down on its imaginary time by adding a perpetual loop. There is no original ‘before and after’ and also no specific space or time that is chosen out of ‘reality’, so something like a psychological rupture occurs when it is brought into the framework of a lived interval. I think the autonomous and abnormal time of the still-life is actually normalized by this process and that is what is really unsettling. This is hard for me to apprehend though, because I filmed it – it exists as a memory as well. -

www.lavalette.com/a-conversation-with-owen-kydd/

Owen Kydd‘s works are durational photographs made on video. Born in Calgary, Alberta in 1975, Kydd moved to Vancouver, Canada where he graduated from Simon Fraser University with a joint degree in Film and Fine Art. Over the past decade he has presented his work in numerous group exhibitions, including 2009’s “Sentimental Journey” at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Kydd currently lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Install of Knife (J.G.), 2011

© Owen Kydd

Lucas Blalock: Can you talk about the transition in your work from more episodic videos that produce a sort of serialized experience to the very tightly contained loops you have been making recently? I further wanted to ask a sort of goofy question about whether you think of these static, durational, looped pieces as still films or extended photographs?

Owen Kydd: I began by working with a duration of about 30 to 40 seconds per image. I found it was a good length to investigate still/motion, because it seemed enough to provide the manifest of a moment while also giving me the chance to create a montage. I made projects that would slide between a series of 9 or 10 of these images (with ellipses in between). Through this process of looking and editing I began to learn more about making pictures that responded to an extension, and I eventually felt like I could make some singular works.

One thing I found was that durational photographs worked better when they lost the indicators that tied them to a past, and began to confuse the moment of filming with the experience of viewing. Cinema or video works that have a long duration usually quote a recorded or lived time, and even in early pieces like Warhol’s Empire, which is close to losing its temporal markers, one is always made conscious of at least the possibility of an end point. This awareness could also be the tied to the projector’s flicker and the grain, but I also have found this condition in more recent video works. I am interested in trying to locate a more hallucinogenic or endless quality.

Still from Sighting, 2010

© Owen Kydd

In terms of the loop’s designation, I can say that when I think about making a still film, I think about changing a momentum and this feels decisive. But when I think about extending photography it suggests continuing a photograph’s inertia, and this seems more indefinite. My works are technically films because they rely on apparent motion, but the movement is limited within the frame, the effect is minimized, and often the same image is overlapped for many seconds without interruption. This process allows me to consider how a photograph can involve itself in motion.

LB: It is interesting to me that through this ambiguity between the still film and the “durational” photograph you end up bringing into question the boundaries of the device and even the strict usefulness of these categories. I feel that this is akin to the kind of interrogation that has prompted artists of late to return to the darkroom (amongst other strategies), but we are really discussing different limits here altogether.

OK: My pieces are exhibited on backlight screens or monitors. So, as with photography, there is a picture merged with a surface, albeit one that has a CFL light and a refresh rate. I feel that there is still an implicit tension between the screen and the subject. And because I am interested in making a picture of something in the world, I hope this tension presents something like the “possibility of reference” (to borrow Walter Benn Michael’s terms) rather than a fight against it. This is wrapped up in the forced distinction that the flatness of the photograph (and here, the screen) must make between itself and the exterior of the object it depicts, and this is a separation that I’m not sure fully exists in the projected image. I can also say that (with the monitor in mind) I find myself looking for specific surfaces.

Still from Yucca Color Shift, 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: Thinking now of the refresh rate, I am also beginning to feel two competing senses of time in these works – one that relates to the possibility of a totalizing photograph achieved through massive accumulation and the other a very slow, meditative temporality that fluidly elongates our looking.

OK: I think the temporal modes you are describing always appear together, although in different ratios, and probably stem from distinct types of photographs; the totalizing image probably begins with a snapshot while the more meditative likely comes from genre imagery. I made a picture of a carving knife in a store window that I think begins with the former. It has the found street ambience of an object that has been framed or chosen out of a passerby’s field of view, and in this sense it is a snapshot – a photograph that exemplifies an instant of lived time.

The Knife begins with this traditional correlation, where a frozen segment of time comes to denote its opposite – that is, fluidity. It adds back the perception of lived time, and this is mixed in with the occurrence of watching the video. In this sense I am trying to intensify the elongated sense of looking that is less pronounced in the imagined photograph of the knife, or the moment the head or camera turns to see it. It reenacts the moment the image was taken.

Still from Knife (J.G.), 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: Your description makes me think of Barthes and the melancholy that he associated with the temporal/photographic relationship. I am wondering if you could talk a little more about what you meant by “looking for specific surfaces”?

OK: You could say it’s a bit like adding-back-in Barthes’ lament, trying to apply duration but after the fact, and usually to an image that doesn’t contain a high degree of trauma in the first place. I’ve been concentrating on documentary or street images for this, somewhat to the chagrin of photographers in my life, because I find these images fit the performance better. I think the pictures I’m looking for also have something to do with that sense of inertia I was describing, not necessarily in terms of a compositional arrangement that draws the eye around the image, but more in terms of the things themselves, objects with a resistance to change. The monitor contains this same constancy, always on, or sleeping, it’s pixels perpetually repeating in the same place.

LB: There is something rather sci-fi about that and it is interesting to think about this stillness or constancy as a cultural metaphor of the digital age where the same binary code and pixel matrix underwrites an extraordinary breadth of information. Seeing the material of the “information super highway” as inert opens up some really unusual relationships to the inertias of the objects. For me these objects occupy a really tense environment. To stand still for some duration in the world, particularly without peripheral vision, as the space of your videos ask us to do, introduces a sense that something could “happen” at any moment. But for me it is not so much that I am waiting for something to take place in the video as much as I find myself bodily anxious as if the parameters of vision leave me both highly attenuated and at the same time vulnerable.

OK: That’s a great way to describe that sense of anxiousness. I think it stems from the fact that the snapshot image is made continually strange by duration, instead of being completed by it or reassured by it. When time is added, it is akin to an accumulation of snapshots all pointing to the flow of time, or the ‘before and after’ of the moment the knife was photographed. As a series it could appear as a bit of a paradox. But at 30 frames per second and 60hz, the accumulation masks the illogical nature of the sequence. The result is an unreal and impossible time and I think the ultimate effect of this is a more traditional ‘distancing’ between us and the picture, albeit a heightened separation.

Still from Canvas Leaves, Torso, and Lantern, 2011

© Owen Kydd

LB: To end I’d like to ask about Canvas Leaves. This is a new work that uses the same presentation device to ponder a very different, highly contrived tableau.

OK: Canvas Leaves is intended to reverse the distancing process. It is a studio-set with a window box chiaroscuro made as a compendium of several storefronts on Pico Boulevard. Everything in the arrangement is plastic or artificial and even though it is static, I tried to make its arrangement unpredictable. The white canvas leaves hanging upside down, rotate left and right with the flow of air in the room (I had to rent an air-conditioner because it was a really warm August).

I hope in a way this piece takes a type of still-life that concerns the effect of time across objects, and doubles down on its imaginary time by adding a perpetual loop. There is no original ‘before and after’ and also no specific space or time that is chosen out of ‘reality’, so something like a psychological rupture occurs when it is brought into the framework of a lived interval. I think the autonomous and abnormal time of the still-life is actually normalized by this process and that is what is really unsettling. This is hard for me to apprehend though, because I filmed it – it exists as a memory as well. -

www.lavalette.com/a-conversation-with-owen-kydd/