Novi urlici iz jame.

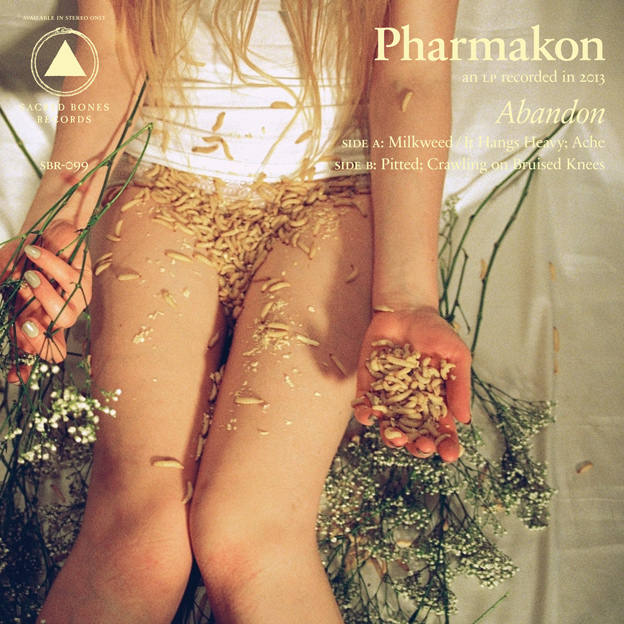

Margaret Chardiet was born and raised in New York City She has been making power electronics/death industrial music under the name Pharmakon for five years. As a founding member of the Red Light District collective in Far Rockaway, NY she has been a figurehead in the underground experimental scene since the age of seventeen. She points out that the environment there amongst so many other experimental artists (amongst them Yellow Tears & Haflings) inspired her to keep making increasingly challenging work. She describes her drive to make noise music as something akin to an exorcism where she is able to express, her “deep-seated need/drive/urge/possession to reach other people and make them FEEL something [specifically] in uncomfortable/confrontational ways.” Engineered by Sean Ragon of Cult of Youth at his self-built recording studio Heaven Street, Abandon is Pharmakon’s first proper studio album and also her first widely distributed release.

Unlike other experimental projects, Pharmakon does not improvise when performing or recording. She is concise and exact; each song/movement is linear with a clear trajectory. Perhaps more than any other style of music, noise is a genre almost exclusively dominated by male performers. Spin Magazine is apt to point out that her,“perfectionism might explain why her recordings are few and far between — a rarity in a scene where noise bros are want to puke out hour after endless hour of stoned basement jams into a limitless stream of limited-edition tapes. Her music may be as cuddly as a trepanning drill, but it’s also just as precise: She glowers in measured silence as often as she shrieks, and every serrated tone cuts straight to the bone, a carefully calibrated interplay between frequency and resistance.” The songs on this album were all written and recorded during a turbulent three month time period during which several fundamental life changes forced her to begin living in a completely new way and in a new space. She describes the lyrical themes of this album as being about, “Loss. Losing everything. Relinquishing control. Complete psychic abandon. Blind leaps of faith into the fire, walking out unscathed. Crawling out of the pit.” - www.sacredbonesrecords.com/

"Abandon," the new full-length album by Margaret Chardiet's Pharmakon project, couldn't open more aptly – a processed scream of anguish is held and allowed to develop, imbued with horror film synth, spoken vocals, and crashing, panning electronic hisses and pops. It's not until three minutes into the track that the listener is given some space, as a lurching bass tone begins to subtend sequenced oscillations, creating a rhythmic bed for Chardiet's truly tortured vocals. While the second piece follows a similar trajectory, all swarming masses of synth skree, stalking rhythms, and menacing vocals, the album's third track, "Pitted," yields something new (and more arresting), possessing a dirge-like component that recalls Zola Jesus at her most primitive. There's a raw physicality to the track that serves as the perfect lead-in to the album's final movement, "Crawling on Bruised Knees," a hypnotizing, largely instrumental work that constitutes a savvy denouement to the proceedings. A harrowing album of stark and brutalized songs, Pharmakon's "Abandon" will likely appeal to fans of Wolf Eyes, Black Dice and, beyond that, industrial music in general. – Alex Cobb, Experimedia

“The Socratic pharmakon also acts like venom, like the bite of a poisonous snake (217-18). And Socrates’ bite is worse than a snake’s since its traces invade the soul. What Socrates’ words and the viper’s venom have in common, in any case, is their ability to penetrate and make off with the most concealed interiority of the body or soul. The demonic speech of this thaumaturge (en)trains the listener in dionysian frenzy and philosophic mania (218b). And when they don’t act like the venom of a snake, Socrates’ pharmaceutical charms provoke a kind of narcosis, benumbing and paralyzing into aporia, like the touch of a sting ray (narkē)” – Jacques Derrida, “Plato’s Pharmacy”

Etymologically, much has been made of the pharmakon as the duality of poison and remedy. But let’s begin instead with therapy: therapeia, curing or healing, from “attend, do service, take care of”: therapon, “servant, attendant.” Margaret Chardiet, a.k.a Pharmakon, is your literal attendant, a presence there in your face, right between the eyes, but you’ll be her servant.

Physical therapy and psychotherapy both heal wounds, exterior and interior. However, as Derrida put it in his reflection on pharmakos, the idea that outside and inside exist separately and separated by a demarcation is a misconstrual; rather, the one contains and creates the other. Or, in Chardiet’s words, “it is about two things that are opposite being the same thing.” There are wounds and wounds: physical and psychic, though for a reductionist, the psychic is physical. Chardiet might treat the one with maggot therapy, the other with the primal scream. She’s not only the attendant, then, but the pharmakon, the one who administers the drugs to the outcast — the outcast nourished at public expense as pre-modern human standing-reserve, before, in times of trouble, s/he (as scapegoat) is beaten on the body and the genitals, and expelled, put to death, burnt.

Those latter verbs provide some clues to Pharmakon’s pulverized atmosphere. Where many death industrial and power electronics acts tend toward childish, black-metal-esque imagery and a tryhard-transgressive obsession with fascism and serial killers, Pharmakon deftly sidesteps these to create something far more disturbing: “I know it’s offensive, but the human race is disgusting. If they think I am acceptable, then I am doing something wrong, frankly” (Chardiet). It’s thereby made apparent that genuine transgression “is not thinkable within the terms of classical logic but only within the graphics of the supplement or of the pharmakon” (Derrida).

Abandon is a sacrificial rite, one that thus brings to mind Teenage Jesus and the Jerks , but it’s not that it sounds like the No Wavers, exactly. Rather, there’s the same quality of a speculum scraping open the Id, transforming logos back into mythos. Chardiet shares Lydia Lunch’s confrontationalism, her need to make her audience uncomfortable, to evidence her contempt and nihilistic rejection of any connection except that in which suffering is inherent (which is all connections), to make the listener feel her pain with an impact visceral as well as aesthetic. “Pitted’s” insistent thud might be the door of Lunch’s closet slamming shut, while in moments like “Ache’s” hindquarters, there’s a certain soughing, defeated dreaminess, which gestures past “dark ambience” (if I may use that awful phrase) to Nico’s frozen warnings.

But let’s leave comparisons aside: Abandon’s hammering slow pneumatic-drill beats are not so much an all-out assault as a grueling siege, in which the beleaguered inhabitants of the psyche find themselves starving, barely existing in a rising cesspool of their own shit and vomit, ridden with epidemic disease, turning to cannibalism and to frantic final Decameronesque debaucheries.

The pharmakon, however, is not only a painful pleasure, the pleasure of the pain that scratching an itch relieves: but “even beyond the question of pain, the pharmaceutical remedy is essentially harmful because it is artificial.” Chardiet’s manipulated and distorted, incomprehensible shrieks and howls not only speak to art-i-ficiality, but remind one of Derrida’s pharmakon as “a literal parasite: a letter installing itself inside a living organism to rob it of its nourishment and to distort [like static = “bruit parasite”] the pure audibility of a voice.” Purity is the last thing that will be found here.

Yet Abandon is an exorcism, and an exorcism is a rite of purification. Chardiet’s brand of catharsis is also a Derridean pharmakon in the sense that it is “an elimination [that], being therapeutic in nature, must call upon the very thing it is expelling […] the pharmaceutical operation must therefore exclude itself from itself.” This is a suffering that calls itself up in order to cathart itself, which expels itself from the mouth, like bile, and is captured mechanically in order to perform the same paradoxical operation of penetrative-aggression-that-is-exorcism upon the listener.

“The pharmakon would be a substance — with all that that word can connote in terms of matter with occult virtues, cryptic depths refusing to submit their ambivalence to analysis, already paving the way for alchemy — if we didn’t have eventually to come to recognize it as antisubstance itself “

Derrida suggests that writing is a pharmakon, but we might engage in our own alchemy, poisonous lead as golden larvae and posit music in that role. The essence of the pharmakon is that it has no stable essence, that it is insubstantial. Despite our fetishization of vinyl and cassette, the literal application to music in the digital age should be apparent. Vinyl, we shouldn’t forget, is constituted from the crudely-transmuted dead; and in regard to “lumpy objects,” as we know the pharmakon by nature contains its opposite. Here and now, substanceless therefore has a necessary relation with viscerality (and that’s how Chardiet wants it). Furthermore, as Derrida adds, since this pharmakon has no being and its effects are constantly changing, it can’t be handled with complete security. Recorded music, like writing, is a de-composition of the voice — the pharmakon “introduces and harbours death […] makes the corpse presentable […] perfumes it with its essence […] a perfume without essence.”

A perfume without essence for les yeux sans visage. “Bewitchment [l’envoûtement] is always the effect of a representation […] the vultus.” Abandon yourself — allow Chardiet’s gaze to hit your face — and be witched. - Rowan Savage

Unlike other experimental projects, Pharmakon does not improvise when performing or recording. She is concise and exact; each song/movement is linear with a clear trajectory. Perhaps more than any other style of music, noise is a genre almost exclusively dominated by male performers. Spin Magazine is apt to point out that her,“perfectionism might explain why her recordings are few and far between — a rarity in a scene where noise bros are want to puke out hour after endless hour of stoned basement jams into a limitless stream of limited-edition tapes. Her music may be as cuddly as a trepanning drill, but it’s also just as precise: She glowers in measured silence as often as she shrieks, and every serrated tone cuts straight to the bone, a carefully calibrated interplay between frequency and resistance.” The songs on this album were all written and recorded during a turbulent three month time period during which several fundamental life changes forced her to begin living in a completely new way and in a new space. She describes the lyrical themes of this album as being about, “Loss. Losing everything. Relinquishing control. Complete psychic abandon. Blind leaps of faith into the fire, walking out unscathed. Crawling out of the pit.” - www.sacredbonesrecords.com/

"Abandon," the new full-length album by Margaret Chardiet's Pharmakon project, couldn't open more aptly – a processed scream of anguish is held and allowed to develop, imbued with horror film synth, spoken vocals, and crashing, panning electronic hisses and pops. It's not until three minutes into the track that the listener is given some space, as a lurching bass tone begins to subtend sequenced oscillations, creating a rhythmic bed for Chardiet's truly tortured vocals. While the second piece follows a similar trajectory, all swarming masses of synth skree, stalking rhythms, and menacing vocals, the album's third track, "Pitted," yields something new (and more arresting), possessing a dirge-like component that recalls Zola Jesus at her most primitive. There's a raw physicality to the track that serves as the perfect lead-in to the album's final movement, "Crawling on Bruised Knees," a hypnotizing, largely instrumental work that constitutes a savvy denouement to the proceedings. A harrowing album of stark and brutalized songs, Pharmakon's "Abandon" will likely appeal to fans of Wolf Eyes, Black Dice and, beyond that, industrial music in general. – Alex Cobb, Experimedia

“The Socratic pharmakon also acts like venom, like the bite of a poisonous snake (217-18). And Socrates’ bite is worse than a snake’s since its traces invade the soul. What Socrates’ words and the viper’s venom have in common, in any case, is their ability to penetrate and make off with the most concealed interiority of the body or soul. The demonic speech of this thaumaturge (en)trains the listener in dionysian frenzy and philosophic mania (218b). And when they don’t act like the venom of a snake, Socrates’ pharmaceutical charms provoke a kind of narcosis, benumbing and paralyzing into aporia, like the touch of a sting ray (narkē)” – Jacques Derrida, “Plato’s Pharmacy”

Etymologically, much has been made of the pharmakon as the duality of poison and remedy. But let’s begin instead with therapy: therapeia, curing or healing, from “attend, do service, take care of”: therapon, “servant, attendant.” Margaret Chardiet, a.k.a Pharmakon, is your literal attendant, a presence there in your face, right between the eyes, but you’ll be her servant.

Physical therapy and psychotherapy both heal wounds, exterior and interior. However, as Derrida put it in his reflection on pharmakos, the idea that outside and inside exist separately and separated by a demarcation is a misconstrual; rather, the one contains and creates the other. Or, in Chardiet’s words, “it is about two things that are opposite being the same thing.” There are wounds and wounds: physical and psychic, though for a reductionist, the psychic is physical. Chardiet might treat the one with maggot therapy, the other with the primal scream. She’s not only the attendant, then, but the pharmakon, the one who administers the drugs to the outcast — the outcast nourished at public expense as pre-modern human standing-reserve, before, in times of trouble, s/he (as scapegoat) is beaten on the body and the genitals, and expelled, put to death, burnt.

Those latter verbs provide some clues to Pharmakon’s pulverized atmosphere. Where many death industrial and power electronics acts tend toward childish, black-metal-esque imagery and a tryhard-transgressive obsession with fascism and serial killers, Pharmakon deftly sidesteps these to create something far more disturbing: “I know it’s offensive, but the human race is disgusting. If they think I am acceptable, then I am doing something wrong, frankly” (Chardiet). It’s thereby made apparent that genuine transgression “is not thinkable within the terms of classical logic but only within the graphics of the supplement or of the pharmakon” (Derrida).

Abandon is a sacrificial rite, one that thus brings to mind Teenage Jesus and the Jerks , but it’s not that it sounds like the No Wavers, exactly. Rather, there’s the same quality of a speculum scraping open the Id, transforming logos back into mythos. Chardiet shares Lydia Lunch’s confrontationalism, her need to make her audience uncomfortable, to evidence her contempt and nihilistic rejection of any connection except that in which suffering is inherent (which is all connections), to make the listener feel her pain with an impact visceral as well as aesthetic. “Pitted’s” insistent thud might be the door of Lunch’s closet slamming shut, while in moments like “Ache’s” hindquarters, there’s a certain soughing, defeated dreaminess, which gestures past “dark ambience” (if I may use that awful phrase) to Nico’s frozen warnings.

But let’s leave comparisons aside: Abandon’s hammering slow pneumatic-drill beats are not so much an all-out assault as a grueling siege, in which the beleaguered inhabitants of the psyche find themselves starving, barely existing in a rising cesspool of their own shit and vomit, ridden with epidemic disease, turning to cannibalism and to frantic final Decameronesque debaucheries.

The pharmakon, however, is not only a painful pleasure, the pleasure of the pain that scratching an itch relieves: but “even beyond the question of pain, the pharmaceutical remedy is essentially harmful because it is artificial.” Chardiet’s manipulated and distorted, incomprehensible shrieks and howls not only speak to art-i-ficiality, but remind one of Derrida’s pharmakon as “a literal parasite: a letter installing itself inside a living organism to rob it of its nourishment and to distort [like static = “bruit parasite”] the pure audibility of a voice.” Purity is the last thing that will be found here.

Yet Abandon is an exorcism, and an exorcism is a rite of purification. Chardiet’s brand of catharsis is also a Derridean pharmakon in the sense that it is “an elimination [that], being therapeutic in nature, must call upon the very thing it is expelling […] the pharmaceutical operation must therefore exclude itself from itself.” This is a suffering that calls itself up in order to cathart itself, which expels itself from the mouth, like bile, and is captured mechanically in order to perform the same paradoxical operation of penetrative-aggression-that-is-exorcism upon the listener.

“The pharmakon would be a substance — with all that that word can connote in terms of matter with occult virtues, cryptic depths refusing to submit their ambivalence to analysis, already paving the way for alchemy — if we didn’t have eventually to come to recognize it as antisubstance itself “

Derrida suggests that writing is a pharmakon, but we might engage in our own alchemy, poisonous lead as golden larvae and posit music in that role. The essence of the pharmakon is that it has no stable essence, that it is insubstantial. Despite our fetishization of vinyl and cassette, the literal application to music in the digital age should be apparent. Vinyl, we shouldn’t forget, is constituted from the crudely-transmuted dead; and in regard to “lumpy objects,” as we know the pharmakon by nature contains its opposite. Here and now, substanceless therefore has a necessary relation with viscerality (and that’s how Chardiet wants it). Furthermore, as Derrida adds, since this pharmakon has no being and its effects are constantly changing, it can’t be handled with complete security. Recorded music, like writing, is a de-composition of the voice — the pharmakon “introduces and harbours death […] makes the corpse presentable […] perfumes it with its essence […] a perfume without essence.”

A perfume without essence for les yeux sans visage. “Bewitchment [l’envoûtement] is always the effect of a representation […] the vultus.” Abandon yourself — allow Chardiet’s gaze to hit your face — and be witched. - Rowan Savage

Pharmakon

New York City artist Margaret Chardiet, aka Pharmakon, makes brutal noise music that aims to both confront people and draw them into her harrowing universe.

By Brandon Stosuy

Photo by Jane Chardiet

Pharmakon: "Crawling on Bruised Knees" (via SoundCloud)

Pharmakon is the noise project of 22-year-old New York native Margaret Chardiet. I first became aware of her a couple of years ago through her incredible live show-- surrounded by electronics and possessed with an intense multi-octave scream, she alternates between staring audience members down and disappearing into her own head.

For four years, Chardiet lived in, and helped run, the Far Rockaway, New York, punk house Red Light District. (I organized a show there in May 2011.) In January, due to Hurricane Sandy as well as personal reasons, Chardiet relocated from Red Light to another DIY space, 538 Johnson in Bushwick. Following this shift, and a handful of CD-R’s and cassettes, she’s about to release her first widely distributed collection, Abandon, on May 14 via Sacred Bones. The five-song record is a journey into Chardiet’s all-consuming approach: across 27 minutes, she moves between industrialized clatter, amped-up death-rants, chilly power electronics, and harrowing apocalyptic soundscapes. At times she brings to mind Diamanda Galás, at others Throbbing Gristle, early Swans, or Prurient. (Listen to the Abandon track "Crawling on Bruised Knees" above.)

I spoke with Chardiet at 538 Johnson about the new album, while other members of the household were getting things ready for a black metal/punk show happening later that night.

Pitchfork: What is the meaning behind Abandon's cover art?

Margaret Chardiet: The artwork was conceived and executed by me, and photographed by my sister Jane. The concept comes from a very real experience where I was throwing away most of my belongings and going through old ephemera, and I found an old love letter. When I opened it, there was a pressed flower that fell onto my lap, along with a bunch of writhing maggots. They had been eating the flower. I had this sense of abandon and I just burned it all. I thought, "This isn't true anymore. I don't own this." And I just let it go.

I recently went through sudden, drastic life changes that were completely out of my control and not by choice. All of a sudden, there was no stability in my life; everything I'd viewed as constant slipped away. In this weird way, it became a catalyst for a drastic shift in my creative life as well. When the bottom falls out and you have to crawl your way out, when you get to the top, you’re alone-- and you're different than you were. If you let go and give yourself over to it, you’re lighter and freer, too. The album’s about fiercely holding on to what's true and unapologetically abandoning what's not.

"I've been going to punk shows since I was a baby-- my dad brought me to a Nausea show and threw my dirty diaper into the pit."

Pitchfork: You grew up in New York and you live in Brooklyn now, during a time when much of the area’s scene involves people from elsewhere. Did growing up in New York affect your approach to music-making?

MC: A huge part of my fascination with this idea of confronting people by being vulnerable-- forcing someone to look you in the eyes, to connect with you-- has a lot do with growing up where there can be someone crying or vomiting on the subway and it's rude to look, let alone offer help. Or you see a parent beating their kid in a bodega and no one does anything. I used to come home from elementary school every day and have to walk around this half-naked homeless woman who was constantly changing clothes. You’re surrounded by people to the point where they’re crowding on top of each other and everyone’s in each other’s faces all the time, but no one acknowledges each other. Everyone has their own little bubble. There’s a huge disconnect. And my desire to make people feel something and truly be present in the moment and connect has a lot to do with that.

Growing up in the city, you see things that most children don’t see. Your childhood is cut short. But it’s not all bad. You have so much access to culture. As a kid, I would go to the Met and spend all day there if I was bored. You grow up faster emotionally and intellectually, too, so you know who you are sooner and enjoy more of your time on earth.

Pitchfork: What are your parents like?

MC: Both my parents are punks; my dad's a guitarist and my mom's a painter. I grew up listening to Dead Boys and the Stooges, and going to punk shows literally from the time I was a baby. My dad brought me to a Nausea show and threw my dirty diaper into the pit-- that young. When I first showed them my music, they said, "Oh, you found the one thing more extreme than how you were raised." Not that it's about that at all.

Pitchfork: How did you arrive at your sound? Did you ever have a project where you were playing guitar or were you immediately drawn towards electronics?

MC: I’ve had a guitar since I was a kid. When I was 14, I started making these horrible recordings of myself in my bedroom. I wanted to do something new. I was making weird noise-y things that were basically bad punk songs with tons of distortion and keyboard. When I discovered noise/power electronics I was like, "This is what I'm supposed to be doing." And then I became really serious about making music.

Pitchfork: You were one of the people who founded and worked out of Red Light District, the DIY space out in Far Rockaway. How did that start?

MC: Me and my friends who played in bands with one another decided that we wanted to live together so that we could practice as loud as we wanted, and also have shows. There was really nowhere good to play in New York for noise and weird underground experimental stuff. I had already been living in Far Rockaway with my dad, so I was like, "There’s this neighborhood where no one wants to fucking live, so you can rent actual houses for cheap."

That was over four years ago. There's an underground network of amazing experimental sound artists across America who would tour and play our venue, and it became an important destination for noisers for a while. Unfortunately, due to Hurricane Sandy, there's no longer a subway going to Rockaway, so shows have pretty much stopped for the time being. But I hope, it will pick back up in the summer. I don't live there anymore, but I plan on staying involved, and all the people that comprised the Red Light are still my dearest friends. We’ll always be a clan.

Pitchfork: Something that impressed me about Red Light District was that people went all the way out there to see music. Especially in New York, where you can walk a block and be at a bar or walk to the subway and be at a show in 10 minutes, it felt special.

MC: Right. Because you had to take an hour and a half subway ride to get there, you didn’t get people who were at the show because they just wanted to party. Cultural tourists are not going to trek that far. Being a part of that community meant dedication. It was a very genuine, honest place.

Pitchfork: When we did the show with you and Peter Sotos and Yellow Tears in 2011, I didn’t see anyone on their cell phones.

MC: That's how it should be. Something is happening and people are actually experiencing it, letting it affect them, contemplating it afterwards, and letting it sink in-- instead of forming their opinion immediately based on what other people will think of their opinion or whether it will make a good post on social media.

Pitchfork: There’s something powerful about being able to forget things.

MC: Yes, because then the stuff that stands out-- the things you do remember-- holds weight, and the other things kind of float off into the distance.

Pitchfork: You don’t have an online presence. Is that intentional?

MC: Yeah. Because everyone is guilty of hearing about a band and then going online and listening to it on shitty computer speakers and thinking, "Let me form an opinion on this immediately." It becomes disposable. What I’m doing deserves to be listened to in a more real way than that. I don’t think it should exist in that internet realm because it can’t be properly understood if you hear it that way. I would prefer it for people to hold a record or a CD and be able to look at the artwork and read the lyrics and have the full concept when they hear it, or to see it live. YouTube videos are never really fully attached to the performance, but people know it’s a document of something else and view it as such, so that's OK.

"I don't want to appeal only to people who are cool enough to have all the right records to understand the backdrop of where my music is coming from. If it can reach the uninitiated, it validates the art."

Pitchfork: Abrasive music has found a bigger audience over the last few years. Do you see what you do as something that could potentially cross over?

MC: The music that I make is about connection and making people feel something, so I would hope that people would be able to latch onto those very raw, human aspects, and that it could appeal to their base inner nature. I’m interested in the idea of the art being valid on its own without context-- of not having to be initiated into experimental music or noise to appreciate it. I don't want to appeal only to people who are cool enough to have all the right records to understand the backdrop of where its coming from. If it can reach the uninitiated, it validates the art.

Pitchfork: Noise is a male-focused scene in a lot of ways. Do you feel like you have to prove yourself to people more because you're a woman?

MC: It’s really not something I think about much. There have been women making noise since the 80s. It’s a male-dominated scene but not more so than any other scene. Pharmakon is me, so I take it very personally. It’s the most sensitive part of my mind and my heart. When I put that out to someone and the only thing they can say is, "oh look, it's a girl screaming," I want to fucking kill them because I’m literally pouring my heart and soul out, being so vulnerable. If the only thing you can grasp from it is something so superficial as the fact that I’m a woman making noise, that suggests to me that you’re not listening very carefully.

INTERVIEW WITH PHARMAKON

I Want to talk about Pharmakon’s beginning. Tell me about where you were in your life, at that time.

Well, I guess at the time that I started Pharmakon; it was a really lonely time… but I think it is not as though ‘the place’ was the reason. It was always dark before then, too. It has always been dark. It wasn’t specifically that time or place that bred Pharmakon; it was something that accumulated over the course of my entire life.

When I found out about noise, it was an amazing revelation. I had found my medium. It was like: ‘Holy shit, this exists, this is what I have been looking for. This is what I have needed for all these years’… I was making this other stuff [music] that just wasn’t doing it for me. Pharmakon was something that had been boiling inside of me for sixteen years. I could finally fucking exorcise it out of me. And look at it. And evaluate it. It wasn’t where I was living or what I was doing, [pharmakon] had been coming a long time.

Do you still feel the same way about Pharmakon?

Yes. Whenever I have problems with Pharmakon I am a complete fucking wreck and I find it really hard to function. I feel very, very depressed, very withdrawn. Very driven, but also very negative. I question myself, and the world, every step of the way.

There is always this part when I break through… I have a fucking revelation and then it’s like … The set has come together. Everything is okay again and I feel empowered and I can move on.

So Pharmakon is the Most important thing in your life?

I could not stop doing it or I would literally go insane. Pharmakon is about a very specific concept, but it is not something that is outside of myself, it is an extension of myself. It is not like Pharmakon is my alter ego or just some alias that I go under. Pharmakon is me. At all times. There is no way to extricate myself from it, which is kind of scary and depressing.

Do you feel comfortable talking a little bit about the specific concepts behind Pharmakon?

The name it’s self is the gateway to understanding what the project is about. Pharmakon is an ancient Greek word; it means both poison and remedy, at the same time. It is the philosophy of something being dual in nature. The idea that something which could harm you, could also help you. But the distinction that is important to me is that the project is about duality, not juxtaposition, it is not about two things that are on opposite sides of the same spectrum, it is about two things that are opposite being the same thing.

There are many themes that fall under that umbrella. If you break [Pharmakon] down to it’s core, it is human connection. It’s not some cold power electronics project. It’s hot and sticky. It is the moisture in your groin. What is it? You can’t help it; it’s just there. I didn’t mean to put it there. I know it’s offensive, but the human race is disgusting. If they think I am acceptable, then I am doing something wrong, frankly.

You’ve had several releases in the past but they are extremely difficult to get your hands on. Very limited editions. Is that intentional or is that just the only means that you had to release your recordings?

It is a little of both. I’ve had many offers from various labels, small, medium and large offering to put stuff out, but I feel that a release as a finished project is something that is so specific, especially in noise/industrial/PE that it is something that has to be whole and complete. Part of that is the music, the lyrics, the artwork and the label that it is on. It does say something about the context of the record.

(Laughs) Well, there is an entire record that I have recorded TWICE. The material was written in 2009 and it still hasn’t come out. I have entire full lengths that I have recorded and have an inclination to release but… I am true to myself. And my art. And if it isn’t what it is supposed to be, I am not going to release it. I am not going to jam for two hours and think that someone is going to care. If I am not completely at peace and passionate about a release, I could not expect

anybody else to give two shits about it. And if they did like it, I would be extremely upset at them. I would rather have someone hate me for the wrong reasons than like me for the wrong reasons.

The accidental part is that I mostly focus on live performance. Pharmakon is a live project, essentially. I am, right now, moving more towards recording but it has also been really important to me to play live because of the experience that it is.

Do you think it is more important for people to see you live than to listen to a recording? What is going on before, during and after a Pharmakon live show and how do you want people to feel when they see you perform live?

I think it is important to see my project live. I think if you are casually watching videos on youtube, or you are hearing one release or a collaboration that I have done with someone else you have absolutely no scope of what the project actually is. Live performance is incredibly important to me because live performance deals with the intangible and the impalpable. It deals with the “x-factor”, the other thing that is in music that cannot possibly come across in recording. Performance deals with a personal connection to other people through the music. Obviously, this is experienced through recording, but live, it is a completely different thing.

Connection to the audience is something that is incredibly important to me. It is a weird, parasitic, symbiotic relationship that I have. I feed off the audiences energy. But they throw back what I am feeding to them. You can play a show to three fucking people, and it is in some weird basement that smells like shit and can play through a PA that sounds like somebody farting underwater and you can have the best fucking show. Those three people can know you and understand your music and feel it and give you that energy that you need to kill it. Other shows, you can be there, and there can be a bunch of people but…

There are many different ways to connect to an audience, too. Over the years I have experimented with many different ways. People who go to a live performance have a need to connect with other human beings. Currently, in the 21st century, when we have all this technology that makes [connection] easy… It is cheapened, a lot. People don’t know how to physically and viscerally connect anymore. It is tragic…

The person who is performing has to have a need to connect. It is perverse. And I’m a fucking pervert; I need to connect with the audience in a way that is uncomfortable. Maybe it is something as simple as looking into people’s eyes.

Even that makes a lot of people uncomfortable.

It does. And it is funny, too. Some people try to laugh, like it’s not big deal. I look into their eyes the longest; because they laugh out of nervous laughter. I am saying what I need to say, and I am looking them in the eyes and they are laughing. They are uncomfortable and I keep looking. Eventually, they start to get more comfortable. They stop laughing. It’s not funny anymore.

But my favorites are people that I am not reaching. My favorites are when I am looking into the audience, and I am telling them something and they have a disconnect and they think that they can look at me and not have a connection with me. No. I am getting inside of you. Right now. No matter how they decide to react, I have made them react. That is my control.

So we are talking about levels of connection. There is something as simple as looking someone in the eye and then it goes to more aggressive behaviors, which are appropriate sometimes. A long-standing tradition in power electronics.

You’re chipped tooth looks really good, by the way.

Thanks! That aggressive approach is sometimes appropriate or needed but is not always. It is typically what I am the least interested in, but it is somehow what people seem to perceive my contact to be. What I am really more interested in is something that I have been experimenting more with recently, which is what happens… At the Tesco USA show, or something.

There are a lot of people at the show. I am up on the stage, kind of separate. I was interested in breaking that boundary and come into the audience. It wasn’t an aggressive thing, where I have some sort of ego or bravado to say I am this ONE person in a couple hundred and I can fucking intimidate you. It is not about intimidation. It was me wanting to be touching a specific person in the audience: I am touching you; I am saying this to you. It might make you feel extremely uncomfortable, but do you think that it is more comfortable to be on stage with all these people having access only to you? No.

You know that everyone in the room is looking at you. If not they are looking at their phone or something, but guess what? I am going to fucking make you look at me. That is a problem with live performance. A lot of people in the audience are more interested in seeing the other people at the live performance as opposed to the performer.

They want to be seen. Fuck that. If you are coming here and you have any idea what this genre of music is about, you should be able to handle me caressing you and coming up behind you.

WARNING.

Warning. I am going to look you in the eye. Guess what? That is the most basic form of human interaction. I swear to fucking god, 75% of the population cannot handle it…we live in an age when you don’t have to look people in the eye. How many fucking parties have you gone to, where half the fucking people there are looking at their fucking Iphones, talking to people who are not at the party. About the party. They are taking to someone on the phone because I don’t actually want to be present. Live performance is about presence.

Live performance is also sonic. The sonic presence of live performance is something that you cannot get from recording… The presence of the sound mixed with the psychological and emotional and artists’ presence of the performer and the energy of the room… Which is what I am talking about when I talk about ‘x-factor’, that. All this stuff I do with connection is digging at people trying to get at that thing, that ‘x-factor’. That thing that you can not explain after going to see a live performance, this thing. It is not that it sounded great; it wasn’t that the performer was flailing around on stage or something like that, it is just the energy in the room, collectively, and that requires other people.

It is so interesting to watch the connections that you make with people, sometimes. For, example, Tesco fest. I also get my rocks off watching you perform and watching other people’s reactions to you performing live. Watching people squirm. But I felt like people were scared of you. A lot of people only know a little bit about you, or have heard something about you and don’t know what to expect. When you went into the audience, it was like you could feel collective discomfort in the room because people didn’t know what was going to happen next.

It is a powerful thing because people think that aggression is the way to influence people or to get under their skin. But when I went out into the audience, the moshing stopped, and that was what I wanted. It was a tender thing… I am not going out into the audience and pushing people… I am a five-foot tall girl. I look like white bread, whatever. Aggression is not the tradition of power electronics that I am grasping from. I think it is much more powerful and much more threatened by human interaction than the bravado of ‘I’m tougher than you’. That is really important. When I am performing, and I touch someone on the shoulder, everyone in the audience is wondering who is next. They are scared of that, and why? Right?

That is why live performance is important to me. This is a solo project. It’s just me. I am responsible for all the material, content, concepts, words, electronics, vocals, recording, and performance… I play by myself. But live, there is another layer. It is not as though the audience are collaborators, but there is something for me to suck up.

Do you have any experiences with people who just don’t get it, that stick out in your mind at all? How do you deal with people who just don’t fucking get it?

This is the thing; people will not come up to you after a show and say, to your face that they don’t get it. If they don’t get it, they go on the computer and talk shit about you. They don’t talk shit to you. If someone has a problem with what I do, I fucking DARE them to come up to me and tell me what they think about it. And I will talk to them. I will be fucking psyched. But guess what? Not a single person has ever done that.

People don’t ever ask you questions about what you just did after a performance? Thoughtfully? Or even unthoughfully? Drunkenly?

Questions, no. People have given me ‘statements’…I get a lot of comments… ‘YOU GO GIRL! That is empowering! It is great what you are doing as a girl!’ …. Do [they] think that gender was the major factor in play? Do [they] think that performance was about gender? Fuck off. It is really trivializing. I wish they didn’t like me. I would rather have someone hate me for the wrong reasons than like me for the wrong reasons. Can I piss during this interview?

Can I record it?

YEAH! [Margaret records a steady stream]

So what is the climate in noise right now? A lot of people that used to do harsh noise have gravitated towards doing more industrial stuff, or techno or dance. I know that you are a fan of some of these artists, but what is it like being a power electronics artist right now?

I do feel fairly lonely. Especially regionally. From what I have observed in the meager five or six years that I have been involved with this there are so many waves. Shit comes in and out of fashion and frankly I don’t really care. I guess when you are making noise or industrial or power electronics you don’t get much feedback as it is. I feel as though I create in a vacuum all of the time. So weather or not there is an appreciation, or a space, or a community that appreciates what I do specially, I am going to keep doing what I do.

In 2006, I felt like there was more of a community for p.e. and noise, harsh shit. And now it’s not so much. But, I also have this privilege of being a part of a group of friends that are insanely critical and supportive. I am extremely lucky to have people around me that hold me accountable for what I do, regardless of the genre. I feel that the art that I make is outside of genre. It doesn’t matter weather of not power electronics or noise are popular at the moment, because that is what this project is and I will make it regardless of weather people like it or not.

We’ve had a hard time booking shows at our house recently, because there are simply not that many good projects around anymore. So we’ll have tours coming through, and we wondering who we will book on the show and it’s crickets. There are not that many good bands.

Even in New York City.

Even in fucking New York City! We are in a bit of a lull point, but I don’t really care. It picks up, is farts out, it picks up it farts out. … To me, Pharmakon is a painful project. And it will always be painful. But never more or less depending on the climate.

Speaking of community, you live at a venue in Far Rockaway. Far the fuck out.

There is a reason why “far” is part of the name.

It is kind of lawless over here. It is like Wild West by the sea. It is a little bit scary. As far as location, it is isolated, but you have an inspiring group of friends that you live with. What is the Redlight District to you and how do you feel after Nick (Diaphragm, former room mate at RLD), Jesse Allen and Jackie (Very close confidants to all the room mates at the RLD) all moving away at the same time.

It’s funny. This is actually an extremely simple answer to a very complicated question. Redlight District is a group of friends. There may be 13 or 15 bands that come out of our group, but it’s really just a couple dudes connected on a very important level who make art together. And so the fact that Jackie, Jesse and Nick moved away doesn’t make them any less close to us. This is our family. What we have as a group of people is love for each other.

I don’t use the word love lightly. Love to me is something very rare. Very exotic, foreign. Hard to understand. And yet, I am so fucking lucky because I exist within a group of people who love each other. Who can fucking say that?

These are friends that transcend periods of time and space. Literally, the Redlight District is something that exists nowhere. We live in this house. It doesn’t fucking matter. Here is a set of people who have found that every single person feels [love] for every person in a group of people. This is something that does not occur, typically.

A lot of the Redlight District went to college together for sound. All of them say that what they learned had nothing to do with their schooling, but through the people that they met through that experience, and that is the group of friends that we have right now. It is something that I can’t explain and frankly I do not have the right to explain it. None of us individually have the words to do that. Gebo, the rune, the one that looks like an x, that the Nazi’s misused… The idea that the sum is greater than it’s parts. That is what the Redlight District is. Individually, we wouldn’t have what we have together and space and time cannot fuck with that. People can live wherever the fuck they want, we still have that.

But they try to insert themselves into it. People try to ride your collective dick a lot.

You can always spot a phony,

So, obviously there is inspiration is the Redlight District but where else do you find inspiration?

People are always like ‘what are your influences’, but you are asking what inspires me… Inspiration is life. Inspiration is not just the people that I am surrounded by or the music that I listen to, literature that I read. What inspires you to think? Why are you a human and not an ape? That is inspiration.

I understand that you are preparing a new set for a show with Bone Awl. What can we expect? What are you working on? What is changing?

This set is a weird combination/transitional composition between new ideas I had while writing the new Lp, mixed with some shit that I had been putting on the backburner a little bit. Stuff I didn’t want to deal with yet, emotionally. So this is a purge forward, grasping at grandiose ideas for the next phase of Pharmakon. A lurch forward towards what will happen next.

How is recording going for the upcoming LP?

All of the electronics are recorded and are in the process of being bounced. Ryan (Yellow Tears, DYsgeniX, etc) is helping me record on an 8-track, which gives it a full sound. The vocals are next, so I guess I can tell you after that. That is always the most harrowing, difficult part of the process I think. It is all I have been focusing on lately. When you say ‘how is it going’, I don’t know how to respond to that. How is my life going? I’ve been obsessed.

You go to school for visual art, and you are a visual artist as well, so what are the differences for you between visual art and noise? What do you get out of visual art that you do not get out of noise? Pharmakon does not satisfy all of your creative urges… you still feel the desire to make visual art.

All of the art that I make starts first and foremost with a concept, an idea. Then I scramble and claw at a way to produce this concept, to express this concept. I believe that different ideas and concepts need to be produced in different ways. Not every concept can be funneled into the same process. The same way as Pharmakon is an extension of myself, the same goes for my visual art. It’s just different ways that it is expressed.

Margaret posing with her mummifying severed duck head, which will be used in a visual piece at a later time.

The last question is a little bleak. You’ve been doing Pharmakon for a long time. Will it ever be over? How will you know that it’s over?

When I die.