http://jonrafman.com/

excerpt on vimeo

Kad se jednom stopimo sa zlom Umjetnom Inteligencijom živjet ćemo vječno, neće nam dati da umremo, a stalne noćne more bit će naše jedino iskustvo.

Play // Dream Journal: An Interview with Jon Rafman

Article by Penny Rafferty in Berlin // Friday, Oct. 06, 2017

Shag carpet fills one room at Sprüth Magers in Berlin, and eight ambiguous, lounging foam figures recline in the darkness. Waiting for your own body to slip into them, or perhaps plug into them, they vibrate to every action on screen, sending a shiver up your spine that could almost be comforting. This elaborate set is the viewing station for Jon Rafman’s new work ‘Dream Journal ’16-’17’, an hour-long CG animated film, which is scored by the famously captivating musicians Oneohtrix Point Never and James Ferraro. The video explores nearly every terrain Rafman’s visual landscapes have allowed us to visit over the years, including computer games like ‘the Sims’ and ‘Street Fighter’ and childhood cult classics like ‘The Goonies’ or ‘Alice in Wonderland’, albeit in a strange, rough computer-generated imagery that is doused with sexual motifs, abstract blood splatters and comic couture allegories. Rafman grounds all this chaos in heroic figures like Joan of Arc, white-turbaned freedom fighters, cute hip amputees and anarcho-feminist insurgents. Rafman has the ability to lead every viewer into a world of play via his screened oracles, having often been dubbed the godfather of post-internet. He constructs the dreams and nightmares you have heard of, seen and will likely encounter in the future. Berlin Art Link caught up with Rafman before his opening to talk play, games, LARP and his never-ending schematics of reality.

Penny Rafferty: I have always wondered if you have a gaming history or if you just stalk the net?

Jon Rafman: There’s some history. I was one of the top Yoshi’s in the tri-state area during the Mario Kart 64 days. And I did get back into gaming while conducting research for my film ‘Codes of Honor’, but I have to say that was in a more documentarian role. Throughout that time I went to Chinatown Fair arcade in NYC almost every day for months and months, I spent hours interviewing pro-gamers about the good old times.

PR: Seductive nostalgia?

JR: Yeah, I’m attracted to this particular obsession and dedication that gamers have, as well as the extremely ephemeral histories that gaming communities have built up. I can see both the Sisyphean quality and the tragic beauty they inhabit. Gamers attempt to master something that is always becoming obsolete. For me, this is an apt metaphor for the accelerated age we now live in.

PR: It’s funny you mention the age we live in, I’m always finding moments of déja vu in your work. I find myself questioning my internal mind’s eye. Did I hear/see that before or some remix of that image, clip, sound. Your work is ultimately impersonal, due to its nature. Of want for a better word, fishing (pulling images via the internet) hence personal to all with its chopped, glitched narratives. We have almost seen it all before.

JR: Well, the way we see the world is deeply affected by the media we consume, especially early on in life. My process really varies from project to project, but as a practice it usually begins with the “stalking” you mentioned before. I have enormous treasure troves of found material. Often there is either a central image, mood, or memory that is the guiding force that I’ll build the work around. And a lot of times that sense of déja vu, or a sense of the uncanny, is condensed into that particular image/narrative and I build onto that.

PR: So does that make you the protagonist, the anthropologist, or the director?

JR: I’d say I’m the director first. I have definitely been a protagonist in some early video works, usually in the form of an exaggerated obsessive version of a certain ideal. And yes, sometimes I take on the role of a very amateur anthropologist.

PR: You’re about to participate in the ‘Play Co Summit’, that Ed Fornieles and I are organising in London. I think Role Play is drawing in a lot of people in the arts who work in a cross disciplinary manner. What drew you to RPG, LARP and bleed (life and play crossover)?

JR: I’ve always been fascinated by Live Action Role Playing, which comes out of my love of fantasy, sci-fi, virtual worlds and gaming. Today it feels more relevant than ever: life itself has begun to feel more and more like a performance and so LARPing feels increasingly poignant as a way to reflect reality.

PR: ‘Sticky Drama’ is one work that stood out to me, as far as seeing bleed being explored explicitly with on and offline imaginariums in your work, and also its ability to explore notions of collective, cross-generational imaginations was really refreshing,

JR: All my work deals with those themes to some degree. The reason ‘Sticky Drama’ probably stands out so much is it was the first time that I worked in live action film and attempted to create my own virtual world in the flesh. Throughout my practice, I have tried to create different poetic universes, each with their own internal logic. In the case of ‘Sticky Drama’, Lopatin and I were pulling from everything from LARP culture to 80s and 90s body horror, to kid adventure films.

PR: That makes sense especially as I see the death drive so fervently in that piece: the death drive becomes a sort of euphoria in the film, like the end of the game is the high you yearn for as a player and director. In the film the chords of Oneohtrix Point Never slash through the walls of this cd-clad-micro blonde girl’s bedroom, it screams 90s revival but in the same way total euphoria, like hearing the happy hardcore beats of ‘Fly on the Wings of Love’ or ‘Better Off Alone’ does. The walls start to drip with slime, the protagonist spins and swirls in ecstasy of her/our impending doom or salvation. End game your ultimate love?

JR: If you look at things from a certain distance the desire to save yourself and to destroy yourself start to merge into one another. I believe the only way to achieve liberation is to understand the nature of our entrapment.

PR: Hence why you often address the traditional role of the inactive viewer, instead providing immersive viewing scenarios such as ‘Still Life – Beta Male’, which allows the voyeur to sit in a ball pool of pearls to comfortably float as the found-imagery plays out; or slip into the soft, waist-clinching seats of ‘Mainsqueeze’. Is this about the gaze, or concentration, or a tactile suggestion to watch?

JR: All of the above. I try to create a formal, sculptural or architectural dialogue between the themes and content of the video, and how they are physically experienced.

PR: Is your work was alluding to the past or the future or a timelessness?

JR: It’s about the present, which contains both past and future. Just as each new age requires a new confession, each era’s vision of the future reveals something about that particular present. In the recent modern past, Utopian visions of the future were prevalent and many were replaced by postmodern dystopian visions. I’m definitely curious what will come next, how our vision of the future will transform again.

PR: Will you make a wild guess?

JR: We will all be uploaded into an evil AI, tortured for all eternity, and never allowed to die. In this sense humanity will have finally achieved immortality, but it is a lot less fun than expected because we will all be endlessly suffering voiceless avatars.

Shag carpet fills one room at Sprüth Magers in Berlin, and eight ambiguous, lounging foam figures recline in the darkness. Waiting for your own body to slip into them, or perhaps plug into them, they vibrate to every action on screen, sending a shiver up your spine that could almost be comforting. This elaborate set is the viewing station for Jon Rafman’s new work ‘Dream Journal ’16-’17’, an hour-long CG animated film, which is scored by the famously captivating musicians Oneohtrix Point Never and James Ferraro. The video explores nearly every terrain Rafman’s visual landscapes have allowed us to visit over the years, including computer games like ‘the Sims’ and ‘Street Fighter’ and childhood cult classics like ‘The Goonies’ or ‘Alice in Wonderland’, albeit in a strange, rough computer-generated imagery that is doused with sexual motifs, abstract blood splatters and comic couture allegories. Rafman grounds all this chaos in heroic figures like Joan of Arc, white-turbaned freedom fighters, cute hip amputees and anarcho-feminist insurgents. Rafman has the ability to lead every viewer into a world of play via his screened oracles, having often been dubbed the godfather of post-internet. He constructs the dreams and nightmares you have heard of, seen and will likely encounter in the future. Berlin Art Link caught up with Rafman before his opening to talk play, games, LARP and his never-ending schematics of reality.

Jon Rafman, ‘Dream Journal 2016-2017’, Installation view, Sprüth Magers, Berlin, 2017 // Photo: Timo Ohler, Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers

Jon Rafman: There’s some history. I was one of the top Yoshi’s in the tri-state area during the Mario Kart 64 days. And I did get back into gaming while conducting research for my film ‘Codes of Honor’, but I have to say that was in a more documentarian role. Throughout that time I went to Chinatown Fair arcade in NYC almost every day for months and months, I spent hours interviewing pro-gamers about the good old times.

PR: Seductive nostalgia?

JR: Yeah, I’m attracted to this particular obsession and dedication that gamers have, as well as the extremely ephemeral histories that gaming communities have built up. I can see both the Sisyphean quality and the tragic beauty they inhabit. Gamers attempt to master something that is always becoming obsolete. For me, this is an apt metaphor for the accelerated age we now live in.

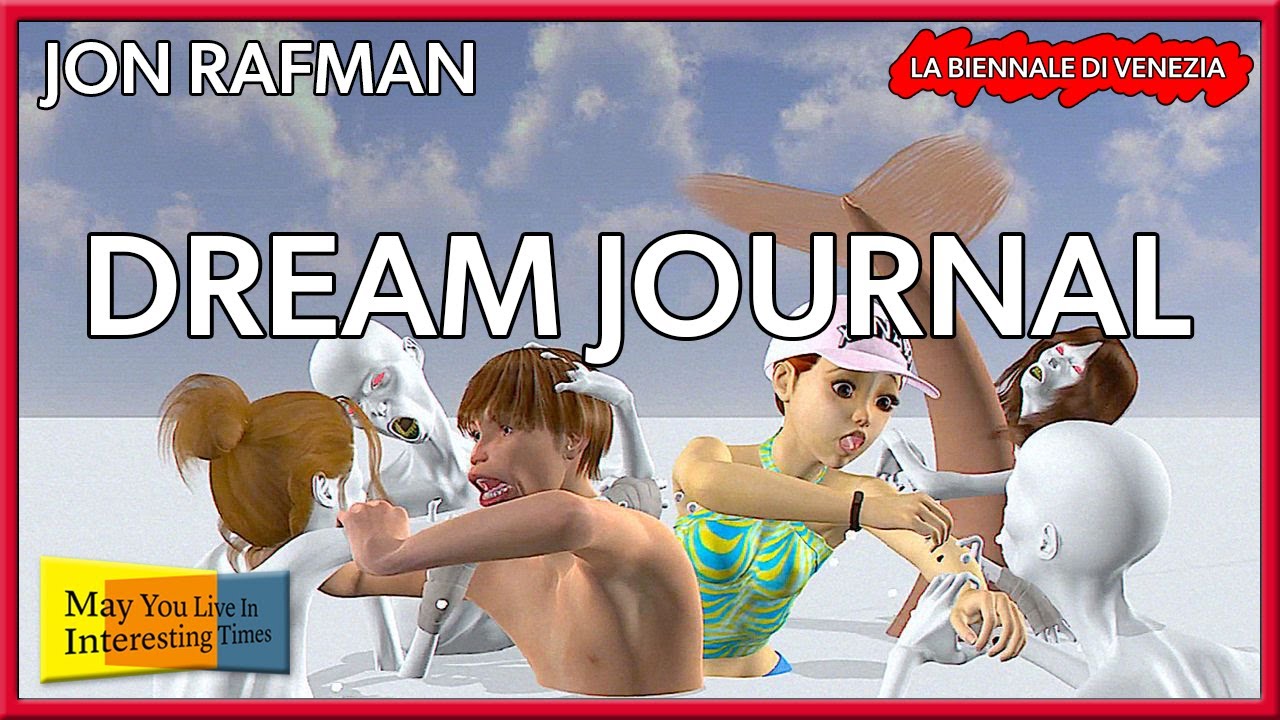

Jon Rafman: ‘Dream Journal 2016-2017’, Video Still // Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers

JR: Well, the way we see the world is deeply affected by the media we consume, especially early on in life. My process really varies from project to project, but as a practice it usually begins with the “stalking” you mentioned before. I have enormous treasure troves of found material. Often there is either a central image, mood, or memory that is the guiding force that I’ll build the work around. And a lot of times that sense of déja vu, or a sense of the uncanny, is condensed into that particular image/narrative and I build onto that.

PR: So does that make you the protagonist, the anthropologist, or the director?

JR: I’d say I’m the director first. I have definitely been a protagonist in some early video works, usually in the form of an exaggerated obsessive version of a certain ideal. And yes, sometimes I take on the role of a very amateur anthropologist.

Jon Rafman: ‘Transdimensional Serpent’, 2016

Virtual Reality video installation, developed with Samuel Walker

Installation view Frieze London 2016 // Photo: Damian Griffiths, Courtesy of the artist and Seventeen, London

Virtual Reality video installation, developed with Samuel Walker

Installation view Frieze London 2016 // Photo: Damian Griffiths, Courtesy of the artist and Seventeen, London

JR: I’ve always been fascinated by Live Action Role Playing, which comes out of my love of fantasy, sci-fi, virtual worlds and gaming. Today it feels more relevant than ever: life itself has begun to feel more and more like a performance and so LARPing feels increasingly poignant as a way to reflect reality.

PR: ‘Sticky Drama’ is one work that stood out to me, as far as seeing bleed being explored explicitly with on and offline imaginariums in your work, and also its ability to explore notions of collective, cross-generational imaginations was really refreshing,

JR: All my work deals with those themes to some degree. The reason ‘Sticky Drama’ probably stands out so much is it was the first time that I worked in live action film and attempted to create my own virtual world in the flesh. Throughout my practice, I have tried to create different poetic universes, each with their own internal logic. In the case of ‘Sticky Drama’, Lopatin and I were pulling from everything from LARP culture to 80s and 90s body horror, to kid adventure films.

Jon Rafman and Daniel Lopatin: ‘Sticky Drama’, Film Still, 2015, Seventeen, London // Courtesy of the artists, Seventeen, London and the Zabludowicz Collection, London

JR: If you look at things from a certain distance the desire to save yourself and to destroy yourself start to merge into one another. I believe the only way to achieve liberation is to understand the nature of our entrapment.

PR: Hence why you often address the traditional role of the inactive viewer, instead providing immersive viewing scenarios such as ‘Still Life – Beta Male’, which allows the voyeur to sit in a ball pool of pearls to comfortably float as the found-imagery plays out; or slip into the soft, waist-clinching seats of ‘Mainsqueeze’. Is this about the gaze, or concentration, or a tactile suggestion to watch?

JR: All of the above. I try to create a formal, sculptural or architectural dialogue between the themes and content of the video, and how they are physically experienced.

Jon Rafman: ‘Still Life (Betamale)’, 2015, Installation view of Jon Rafman, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 2016 // Photo: GJ van Rooij, Courtesy of the artist

JR: It’s about the present, which contains both past and future. Just as each new age requires a new confession, each era’s vision of the future reveals something about that particular present. In the recent modern past, Utopian visions of the future were prevalent and many were replaced by postmodern dystopian visions. I’m definitely curious what will come next, how our vision of the future will transform again.

PR: Will you make a wild guess?

JR: We will all be uploaded into an evil AI, tortured for all eternity, and never allowed to die. In this sense humanity will have finally achieved immortality, but it is a lot less fun than expected because we will all be endlessly suffering voiceless avatars.

‘Anxiety of Mutations’ Jon Rafman’s Dream Journal at Venice Biennale by Piotr Bockowski

The 2019 Venice Biennale presents Rafman’s 3 years of exploration into the 3D simulated environments (2016-2019) that form the feature film Dream Journal (94 minutes). Here Rafman radically experiments with imaginary worlds populated by the obscene diversity of biotech mutants. CGI reveals the dark vitality of techno-materialism that moulds post-human forms with chimeric beasts, monstrous insects and Japanese sexual perversions. BDSM Tokyo schoolgirls eaten out by giant snails cry sperm-milk from Janus faces growing inside their anuses. Their topsy-turvy bodies twist and collapse in an anti-dance of digital butoh and virtual shibari of phantom vectors. They date retarded half-hedgehog half-walrus boys who fight against each other in cage death-wrestling tournaments staged inside dubious techno clubs of tropical spacecraft decor. Xanax girl is sentimentally attracted to one (or two) of them. As she descends on a journey filled with platform computer games like booby traps and post-apocalyptic military bars, she allows for frequent penetrations of medical apparatuses, only to give away her body to techno-shamanist occult rites that disintegrate and transfigure her corporeality further still.

All the spaces and realms of Dream Journal seem to be connected with processes of mutant transfigurations that challenge the human form over & over. The database institution that extracts Xanax girl from amongst the forms of her clones also links distant events through networks of canalizations. Digital excrements become the most fertile media for mutant communications. The shit-hole orifices make sex with various enslaved bodies and feed on their inner organs. In effect, the produce of digi-excremental canal digestion is eventually served as pet food to giant caterpillars that swell and multiply into new energy sources.

Yet, in the midst of Rafman’s accelerating bizzare neo-savagery, he invites moments of gentle sadness. The absurdity of obscene mutations sporadically suspends the characters of Dream Journals in moments of nostalgic stupor. Out of a sudden, the computer game-like actions are interrupted when characters have to disintegrate or remain confined to particular local territories. They surprise us with expressions of disappointment and longing towards what could be described by the Japanese term mono no aware – the subtle contemplation of the transience of things. Those expressions are actually far from dominating the general mood of the narrative but nevertheless, they allow the real anxiety of lived experience to creep into worlds of macabre, detached and fantastical exaggerations. This unexpected and maybe even unwantedly grotesque closeness to unrealistic dreamy whims of biotech visions, imposed on us through sorrow, give the audience a vivid sense of their mediated bodies as processes in the making of unhuman materialities.

Why do all these mutant bodies populate Rafman’s computer screen out of a sudden? Seemingly, there is a certain realization behind Dream Journal that diagnoses digital media as increasingly and obscenely mutagenic. Strange it may appear since the year 2019 has witnessed a wave of censorship of major Internet platforms. Tumblr introduced their ‘safe & trust’ policies of removing pornographic and gore content, Vimeo started deleting many long-living profiles after accusing them of ‘activity primarily focused on sexual stimulation’ and Facebook increased cases of blocking computer-selected profiles in the name of digital ‘family values’. All those vague ethical algorithmic systems, many times short-circuit confused, nevertheless insistently express circular obsessions with human sexuality.

They aim at the suppression of raw drive and desire that may appear aggressive. Standing for controlled concepts of communities, mainstream media policies effectively erase the imagery related to human body reproduction – the infamous nipples, shameful genitals or even more abstract body presentations that happen to involve moist or tense expressions, perhaps suggesting the possibility of secreting glands within hidden orifices. Those policies of familiar communities become somehow uncanny as the meditated families insistently disconnect themselves from technicalities of sexual reproduction. As a reaction, the generative systems of contemporary Internet populations project digital mutant replicants without nipples nor genitals, welcoming monstrous deformities as long as they escape human biology features.

Rafman exposes the fetishistic spillage of repressed desire online, tapping into almost half-century-old Japanese hentai strategies of eluding censorship, which can be considered symptomatic for Internet aesthetics now. Since the 1970s Ero Guro movement in Tokyo, hentai answered to state prohibitions of portraying human genital intercourses by creating fertile subspecies of tentacle monsters that twist around no-longer human bodies and penetrate their dislocated orifices gaping in-between feverishly multiplying mamillae. Rafman created several side characters directly referencing abused by demons girls of Toshio Saeki and perfidiously manoeuvred the protagonist Xanax girl into bizarre interactions with rapey creatures of hybrid features, merging insectoid bodies with warty overgrowth or mollusc like pseudopods inspired by Horihone Saizuo. Eroticism becomes transfigured here into the primal relation of external digestion. Inside out guts performing pornographic figurations transgress the sphere of human sexuality and pull us into the desperate technological cannibalism of incestuous mutants. Asked in an online interview about his trans-species art of invasive eroticism involving sluggish soft bodies invasions into dehumanized squid women, Daikichi Amano described his desire as “a cockroach that had head and the body separated with the surprise and scary when having begun to run with the head and the body in separate directions.” The broken grammar of this Engrish quotation exposes hybrid nature of fragmented digital bodies in their hypermediated overexpressions. In the same vein, viral social media body performers like Aun Helden use their image manipulation art to castrate sex or ‘anything that presents them as men’, at the same time multiplying what’s considered to be anatomical anomalies. Instead, harmonizing with human forms their corporeal members bulge with black eggs that initiate no-longer-human replication. The shiny surface of the eggs reflects the mutagenic void of computer screens.

Ongoing project Dream Journal presents a feature-film length epic that reworks the traumas of the human body entering the Internet era media mutations. 3D-rendered are the monstrosities bred from the very desires projected by a culture of digital technologies. The plots fork into paranoid networks by pulling the viewer through severely methodic Role Playing Games of creaturely alienations. Jon Rafman made an extraordinary effort to collect spilt phantom limbs and chimerical flesh from all over the deep dark underbelly of the Internet. They are melted into a mythological journey of a near present that our addiction to technological stimuli eagerly evokes.

Legendary Reality, 2017

Poor Magic, 2017

Dream Journal, 2015 - 2016

Erysichthon, 2015

Sticky Drama, 2015

Neon Parallel 1996, 2015

Mainsqueeze, 2014

Still Life (Betamale), 2013

9-Eyes, ongoing

Remember Carthage, 2013

Brand New Paint Job, 2013

Codes of Honor, 2011

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life, 2008-2011

You, the World and I, 2010

Woods of Arcady, 2010

PaintFX, 2009

archive

some texts

The Refracting Eye On Jon Rafman by Bret Schneider, CURA, 2016 (pdf)

Interview with Michael Nardone, Vdrome, 2016

Introduction to catalog by Kevin McGarry, 2016 (pdf)

Infinite Lives: The online Anthropology of Jon Rafman by Gary Zhexi Zhang, Frieze, 2016 (pdf)

This Is Where It Ends: The Denouement of Post-Internet Art in Jon Rafman’s Deep Web by Saelan Twerdy, Momus, 2015

Artforum 500 words, 2014

Interview with Pin-Up, 2013

Interview with New York Times Mag, 2013

Frieze Review of A Man Digging by Galit Mana, 2013

Lauren Cornell on Remember Carthage, 2013

Interview with Creator's Project, 2013

Interview with Aids-3D (Dan Keller & Nik Kosmas), Kaleidoscope, 2011

Rhizome: Codes of Honor, 2011

'Brand New Paint Job' catalog by Domenico Quaranta, 2011 (pdf)

Interview with Lodown Magazine, 2010 (pdf)

Interview with Lindsay Howard, Bomb Magazine, 2010

'IMG MGMT - The Nine Eyes of Google Street View' essay, 2009

16 Google Street Views booklet, 2009 (pdf)

Remember Carthage, 2013

Brand New Paint Job, 2013

Codes of Honor, 2011

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life, 2008-2011

You, the World and I, 2010

Woods of Arcady, 2010

PaintFX, 2009

archive

some texts

The Refracting Eye On Jon Rafman by Bret Schneider, CURA, 2016 (pdf)

Interview with Michael Nardone, Vdrome, 2016

Introduction to catalog by Kevin McGarry, 2016 (pdf)

Infinite Lives: The online Anthropology of Jon Rafman by Gary Zhexi Zhang, Frieze, 2016 (pdf)

This Is Where It Ends: The Denouement of Post-Internet Art in Jon Rafman’s Deep Web by Saelan Twerdy, Momus, 2015

Artforum 500 words, 2014

Interview with Pin-Up, 2013

Interview with New York Times Mag, 2013

Frieze Review of A Man Digging by Galit Mana, 2013

Lauren Cornell on Remember Carthage, 2013

Interview with Creator's Project, 2013

Interview with Aids-3D (Dan Keller & Nik Kosmas), Kaleidoscope, 2011

Rhizome: Codes of Honor, 2011

'Brand New Paint Job' catalog by Domenico Quaranta, 2011 (pdf)

Interview with Lodown Magazine, 2010 (pdf)

Interview with Lindsay Howard, Bomb Magazine, 2010

'IMG MGMT - The Nine Eyes of Google Street View' essay, 2009

16 Google Street Views booklet, 2009 (pdf)