Esencijalni dokumentarist suvremene tehno-znastveno-političke civilizacije.

Moć, znanje i strah.

Filmmaker and Massive Attack collaborator Adam Curtis on why “music may be dying” – and why we need a new radicalism

Adam Curtis believes in stories.

They feed the human imagination and they can transform both people and the world for the better. He thinks that for the past 20 years we have been in a political and cultural ditch because we have, unlike in the past, opted to manage the world rather than try to change it. According to Curtis, this malaise is the unintended consequence of several processes: the rise of individualism and its atomization of society; the now entrenched belief that humans are rigid and unchangeable; and the use of the language of economics to think about the world. The managed world we live in is a static world, haunted by the ghosts of its past.

For 20 years Curtis has used long-forgotten BBC archival footage and dazzling pop soundtracks to tell the stories of curious individuals to get his audiences thinking about how systems of power work. For example, SAS-founder David Stirling’s private mercenary force in the Yemen demonstrated the reluctance of Britain’s old guard to relinquish its Empire; geneticist George R. Price’s grisly suicide underpinned Curtis’ case for free will; and Edward Bernays’ use of his uncle Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories to sell women cigarettes showed post-war America’s culture of consumerism and control.

“Punks don’t like to hear it but they and Mrs.

Thatcher were both on the coattails of something bigger, which was the

rise of individualism.”

His current audio-visual collaboration with Massive Attack’s Robert Del Naja in the atrium of Manchester’s long-abandoned Mayfield train station, forms the centrepiece of this year’s Manchester International Festival. ‘Adam Curtis V. Massive Attack’ features guest vocalists Elizabeth Fraser and Horace Andy doing covers from Barbra Streisand to Kurt Cobain and a soundtrack that includes Suicide and Burial. At points, it’s arrestingly loud – according to Del Naja his audio hire company had to procure more bass speakers than they’ve ever done for a single show.

Throughout the spectacle, Curtis’ paternalistic BBC newsreader voice recites an evocative political essay sardonically entitled ‘Everything Is Going According to Plan’. The essay covers a lot of ground and uses several stories, from the Soviet clean-up of Chernobyl to Jane Fonda’s workout VHS revolution, to tell a tale of how individual freedom, “the prevailing orthodoxy of our time”, might be inhibiting human progress and the creation of a better world. But Curtis says the film is also about how these same forces of individualism could also be shackling music to its past.

“In making this most recent show I’ve begun to actually think about music politically,” explains Curtis to FACT in a Manchester coffee shop. “The thing that fascinates me most is just how stuck music has become. And I love music, I know a lot about pop music, but it is now completely reworking the past, almost archaeologically.”

Curtis believes that political individualism as espoused by Margaret Thatcher and implemented though her neoliberal policies is part of the same wider cultural shift as the individualism that punk rock embodied. The privileging of the individual over the community has, he says, had the unintended consequence of atomizing the world to the extent that today “everything is acceptable and everything is ubiquitous”.

“Punks don’t like to hear it but they and Mrs. Thatcher were both on the coattails of something bigger, which was the rise of individualism where we could be whatever we wanted to be,” he explains. “The Sex Pistols’ song ‘I Wanna Be Me’ came at the same time as a speech by Mrs. Thatcher that had pretty much the same message.

“But punk was the seed of its own disaster just as Mrs. Thatcher was the seed of her own disaster. She was the last politician in Britain to tell a story but it was a story that, like punk, said that you should be free to do whatever you want and that left us trapped in our own rather limited sensations and desires. What we are missing today is that when human beings get together they become more than the sum of their parts.”

“If you listen to Savages, they are archeologists! They are like those people in pith helmets who used to dig up the bones of Tutankhamun.”

Curtis strongly believes that music should serve a greater role in society than mere entertainment. As a child of the 1960s, he believes that music is not a passive thing but has the power to drive changes in society. It is perhaps for this reason that he laments the modern demotion of music as means to simply titillate– a kind of emotional masturbation.

“I love emotions, I’m a very emotional person,” he says, “but how limiting is it to live in a world where your relationship with music is just emotional? It’s appropriate at certain times like when you go dancing or you’re lonely and home late at night, but the idea of being emotional in everything might actually be trapping us into a very limited view of what we are as human beings.

“The focus on our own emotions comes from the central ideology of our time: individual freedom. But what this ideology really says is that what you feel and what you think is everything. Well, actually, human beings can be far more than that. In other circumstances you can lose yourself in something grander, whether it’s for an idea or for love, when you surrender yourself to someone else. These things actually liberate yourself from your feelings and it may be that this idea that your emotions, which this modern music is encouraging to reinforce, might actually be part of the problem because it’s trapping you just with yourself and if you’re trapped within yourself you can’t lose yourself in something grander. It’s not only limiting – it stops the world changing, because it’s only when we are together that we’re powerful.”

The musical – and political – individualism of our times has, according to Curtis, created a static world where music is ubiquitous and, because it is incapable of moving forward, is fixated on its past. Pop music used to look forward, glancing occasionally at the past , but now the past is where it lives. This change was likely catalyzed by changes in music industry. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, sub-cultures became mass-cultures as movements like house, grunge, Brit-pop and even garage were propelled into the mainstream. Napster and the digital revolution made all music, past and present, ubiquitous, creating the ‘I’m-into-a-bit-of-everything’ generation who had total choice. This blurred, and eventually broke, the old tribal divisions in music to the point where now to be in a tribe is to be woefully out of touch.

Curtis says the ‘reinforcement’ of our emotions and sensibilities operates in a number of ways: culturally, through a society that puts a premium on emotions, and technologically, through the algorithms used on websites like Last FM, Amazon and Pandora that usher people towards music they already like.

He cites the example of playing Coldplay during the heartwarming moments of The X Factor as an example of how we are being marshaled to believe there is an “appropriate” emotion for an appropriate time, something he deliberately subverts when making his own films, most notably in ‘It Felt Like a Kiss’.

“I think true radicalism[…]comes from the idea of saying this is a world that has never existed before, come with me to it.”

“If we are emotional, which is not necessarily a bad thing, then what tends to happen is that those with power tell us what’s the right emotion to feel at the right time. Very much like how the Victorians used to have guides to modern manners. I would argue that playing Coldplay behind a moment in The X Factor is the modern version of the Victorian guide to manners.”

“My argument is that we live in a non-progressive world where increasingly we have a culture of management, not just in politics, but everywhere. Modern culture is very much part of this progress. What it’s saying is: ‘stay in the past and listen to the music of the past’.”

“I know everyone loves Savages but if you listen to Savages, they are archeologists! They are like those people in pith helmets who used to dig up the bones of Tutankhamun.

“Savages have gone back to the early 1980s and unearthed a concert of Siouxsie Sioux or The Slits and literally replicated it note for note, tone for tone, emotion for emotion. It’s like some strange curatorial adventure. They’re not new. It’s good to go back into the past and take something and reinterpret it and use it to push into the future but they’re not doing that – they’re like robots.”

“Pop music might not be the radical thing we think it is. It might be very good and very exciting and I can dance to it and mope to it, but actually it just keeps on reworking the past.

“If you continually go back into the past then by definition you can never ever imagine a world that has not existed before. I think true radicalism…comes from the idea of saying this is a world that has never existed before, come with me to it.”

So, if we’re in such a swamp, how do we make music progressive again?

“Well, the ruthless answer is that music may actually be dying at the very moment it is everywhere. There comes a moment in any culture where something becomes so ubiquitous and part of everything that it loses its identity. It will remain here to be useful but it won’t take us anywhere or tell us any stories. It won’t die in the sense of not being here but in the sense of not having a meaning beyond itself. It will just be entertainment. What will happen is that something else we haven’t imagined yet will come in from the margins that tell us a story that unites us.”

At the Manchester International Festival show, Elizabeth Fraser stands half-silhouetted behind the central screen singing in Russian a cover of ‘Yanka’s Song’ by Yanka Dyagileva as the Siberian punk-folk singer’s tale is told in huge letters over the screen, ending with her sad oblivion.

“Outside our fragile cocoon and beyond the reach of the two dimensional ghosts and the enchanting music of the dead,” silently shouted the giant letters across the screen, “the future is full of POSSIBILITY”.

“IT IS NOT PREDICTABLE”…“YOU CAN MAKE ANYTHING HAPPEN”…“YOU CAN CHANGE THE WORLD”…“PLEASE FIND YOUR OWN WAY HOME”.

Exiting into a room filled with a thick fog of dry-ice, lit only by the path of bright searchlights and silent except for the barking of dogs, the message seemed clear: the future may be scary and uncertain, but we shouldn’t be afraid of it.

- Arron Merat www.factmag.com/Adam Curtis on:

Skrillex: “It’s extreme music which is kind of entertaining but it doesn’t tell you a story. It’s a mood, and to be rude it’s a zombie mood. Things like Skrillex are the remnants of the old music carrying on in a kind of zombie-like exaggerated way. It’s stuck, it’s not going anywhere.”

Mumford and Sons: “They are like 18th century squires who ride out on the estate and go on the hovels where their fans live and tell them everything must stay the same. Mumford and Sons are the modern version of “you should know your place”. They’ve gone back to an old cultural folk music – some of which was very radical and a way of challenging power in the world – stripped it of any meaning, and reworked it into this nostalgic thing and put it together with stadium amplification. I can’t bear it, it makes me cry.”

Rihanna v Beyoncé: “I love Rihanna, I love her. I think she’s the best thing in the whole world, whereas Beyoncé is flat mood music for so-called sophisticated urban bars in waterside locations.”

To many in both politics and business, the triumph of the self is the

ultimate expression of democracy, where power has finally moved to the

people. Certainly the people may feel they are in charge, but are they

really? The Century of the Self tells the untold and sometimes

controversial story of the growth of the mass-consumer society in

Britain and the United States. How was the all-consuming self created,

by whom, and in whose interests?

The Freud dynasty is at the heart of this compelling social history. Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis; Edward Bernays, who invented public relations; Anna Freud, Sigmund's devoted daughter; and present-day PR guru and Sigmund's great grandson, Matthew Freud.

Sigmund Freud's work into the bubbling and murky world of the subconscious changed the world. By introducing a technique to probe the unconscious mind, Freud provided useful tools for understanding the secret desires of the masses. Unwittingly, his work served as the precursor to a world full of political spin doctors, marketing moguls, and society's belief that the pursuit of satisfaction and happiness is man's ultimate goal.

For the most crucial 2.5 minutes of the astounding Adam Curtis documentary watch

youtube.com/watch?v=s18vu5tCzsc&feature=player_embedded

The Freud dynasty is at the heart of this compelling social history. Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis; Edward Bernays, who invented public relations; Anna Freud, Sigmund's devoted daughter; and present-day PR guru and Sigmund's great grandson, Matthew Freud.

Sigmund Freud's work into the bubbling and murky world of the subconscious changed the world. By introducing a technique to probe the unconscious mind, Freud provided useful tools for understanding the secret desires of the masses. Unwittingly, his work served as the precursor to a world full of political spin doctors, marketing moguls, and society's belief that the pursuit of satisfaction and happiness is man's ultimate goal.

For the most crucial 2.5 minutes of the astounding Adam Curtis documentary watch

youtube.com/watch?v=s18vu5tCzsc&feature=player_embedded

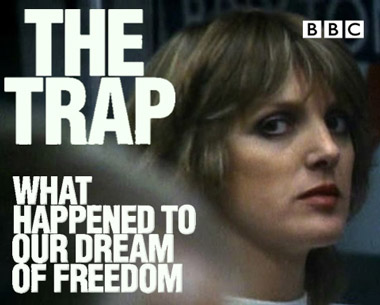

The Trap

This is another brilliant Adam Curtis documentary originally produced for the BBC. It talks about the modern political realities, where the policies came from and the massive failures of those ideals and how they have ended up exactly where they did not want to be.

This episode starts in the Cold War and shows the seeds that were sown to produce the modern political reality.

The title of this episode comes from a paranoid schizophrenic seen in archive film in the programme, who believed her neighbours were using her as a source of amusement by denying her any privacy, like a goldfish in a bowl.

In this episode, the history of brainwashing and mind control was examined. The angle pursued by Curtis was the way in which psychiatry historically pursued tabula rasa theories of the mind, initially in order to set people free from traumatic memories and then later as a potential instrument of social control. The work of Ewen Cameron was surveyed, with particular reference to the Cold War theories of communist brainwashing and the search for hypnoprogammed assassins.

This programme's thesis was that a search for control over the past, via medical intervention, had to be abandoned and that, in modern times, control over the past is more effectively exercised by the manipulation of history. Some footage from this episode, an interview with one of Cameron's victims, was later re-used by Curtis in The Century of the Self series.

Pandora's Box, subtitled A fable from the age of science, is a six-part 1992 BBC documentary television series written and produced by Adam Curtis, which examines the consequences of political and technocratic rationalism.

The episodes deal, in order, with communism in The Soviet Union, systems analysis and game theory during the Cold War, economy in the United Kingdom during the 1970s, the insecticide DDT, Kwame Nkrumah's leadership in Ghana during the 1950s and 1960s and the history of nuclear power.

Curtis' later series The Century of the Self and The Trap had similar themes. The title sequence made extensive use of clips from the short film Design for Dreaming, as well as other similar archive footage.

All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace

The Power of Nightmares

The Way of All Flesh

Archival Trouble

The fiction-free science fiction of Adam Curtis

by Michael Atkinson posted February 16, 2012

One would imagine that a documentary filmmaker working within the auspices of the BBC would have a difficult time establishing a personal voice, rewriting recent history, pursuing his or her own darkest fears, and/or limning a worldview at hair-raising odds with the established media posture. But this is the troubling stealth phenomenon that is Adam Curtis, the 21st century's calm, reasonable, insidious Cassandra, whose accumulating film corpus passes itself off in the mainstream as a set of mere history lessons slouching leftwardly, all about the State of Things and How We Got Here. As the filmography builds, however—with his new three-part film, All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace (2010), what could be characterized as pure-grade Curtis totals over 24 hours of thick archival trouble—it's clear that Curtis is hardly just a television pedagogue. He is, rather, a modern apocalyptist, a "deep politics" practitioner focused on outlining the vectors of force behind recent history that all of us have conscientiously forgotten, and which are largely responsible for the terminally compromised world we live in.

Curtis's brand of deep politics isn't theorist Peter Dale Scott's—he's concerned less with deliberate conspiracy than with the cascade of sociopolitical dominoes, beginning somewhere mysteriously decades ago, tumbling in a semi-secret dialectical train of disaster since, and culminating in flat-out catastrophe, be it 9/11 or the world economic meltdown or merely the Reagan-era state of rampaging consumerist narcissism. Formally, Curtis manufactures his flowcharts with the simplest means available: archival footage, talking heads, calm but ominous narration, associative montage, a pervasive sense of doomsday. All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace is paradigmatic: Curtis begins, as his Richard Brautigan-quoting title suggests, with the familiar suspicion that the mechanization of our lives is winding inexorably toward a dystopian nightmare in which the matrix of microprocessors and A.I.'s will end up commanding us, not vice versa.

But right away it's clear that Curtis isn't hypothesizing about a terrifying future, but unearthing the hidden patterns that have created the present moment. The villains are not machines. Curtis trips backward, as is his wont, to the '50s and the rise of Ayn Rand, whose Objectivist creed in turn gave fitful birth to a spate of influential ideologies, all of which decided that both nature and human society were essentially self-sustaining, equilibrium-seeking logical mechanisms, and could be managed thus. "This is the story," Curtis intones, "of the rise of the dream of the self-organizing system, and the strange machine fantasy of nature that underpins it." The tales he tells to illustrate this harrowing and almost completely overlooked social saga all intertwine, and run from the "spaceship Earth" ideas of Buckminster Fuller, the communes that followed, the pessimistic forecasts of the Club of Rome, the rise and fall of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, the genesis of the wholly fabricated Tutsi-Hutu dichotomy that turned Rwanda into a killing field more than once, the career of Dian Fossey, the late-century rollercoaster of economic feast and famine, and the work of theorist/geneticist George Price, who believed that humans were ultimately the slaves of their own genetic imperatives, and who demonstrated mathematically that both altruism and genocide were therefore rational acts, from "a gene's eye view" of things.

There's more, all of it reflecting back upon now; Curtis is nothing if not a staunch proselytizer for the idea of the past never being quite past. All Watched Over is more than a counter-story. Like all of Curtis's work it is approximately half well-circulated history and half "deep" background—that is, storylines and historical angles that have been pervasively and deliberately neglected by the gatekeepers of knowledge and information. The film feels something like a Craig Baldwin delusion-farce turned chillingly, menacingly factual, and the facts accrete into an interrogation of psychotic hubris. The Frankenstein monster constructed by the scientists and demagogues and politicians in All Watched Over is the last half-century or so of life on Earth, which in its ultimate tally amounts to a scoresheet of unimaginable injustice, mountains of bodies, and untold environmental ruin.

Curtis is in reality telling just one story, again and again in various threads and tangents and in dazzling three- or four-hour chunks, reaching back to the immediate postwar years and then forward to the present over and over, limning an infinitely complex genogram of our present existence. Ironically, for a history-rewriting filmmaker/producer boxing so much information into evenings of television, Curtis is fierce about the disastrous effects brought about by the artificial and intellectualized imposition of order. He began in his present mode with 1992's Pandora's Box, a massive autopsy on the worldwide cataclysms that unrolled as a result of every kind of postwar effort to systematize, organize, compel, and codify humanity, from Soviet over-industrialization to game-theory Cold War strategies to Keynesian economics to nuclear-power utopianism. Politically, this is a rocket targeted not at the Right per se, but upward, at the power elite, whose perpetual folly in trying to maximize profit and control leads ceaselessly to societal breakdown—a condition very often beside the point for the elite in question, once they've stood to benefit. The Century of the Self(2002) goes all attack-ad on this dynamic, specifically homing in on propagandist/marketing mahatma Edward Bernays, and how he used Freudian psychoanalytic insights to initiate the gold rush of institutionalized thought control—advertising, propaganda, public relations—that could be said to absolutely dominate 20th-century public discourse.

Critic J. Hoberman pegged Curtis in a sense when he suggested that his worldview was closer to DeLillo than Chomsky—if we can first take another moment to reflect on the oddity of those choices, that spectrum, in an office at the BBC. True enough, Curtis's corpus has the seething, portentous air of science fiction, without being fictional, and the disconnect there suggests a new kind of culture that may well be a natural byproduct of the postwar era's steamrolling power structures, capitalistic need for growth, ecological devastation, and extra-human technology. Why should the old categories of history, science fiction, journalistic truth, conspiracism and apocalyptic vision retain their mutual exclusivity, as the conceptual barriers between news and entertainment, reality and virtuality, government and corporation, national and global, all vanish like stray broadcast signals? For many of us, a lot of Curtis's historical weaves are a fiction-free science fiction, a massive grid of Orwellian-Dickian-Casolaroesque intimations and eruptions that reveals a nascent totalitarianism spreading like a mushroom colony beneath the surface of everything we see and hear—all of which, of course, is devised and programmed by corporations and governments. If you don't think things have gotten radically different and substantially worse, then you don't, like most people, remember anything significant about the way life was before. As it is, observers who know firsthand about how society chugged, climbed, and conceived of itself before World War II, before Bernays, before the invention of the computer, before the International Monetary Fund, are becoming fewer every year. Attrition will guarantee the absence of informed and memoried resistance soon enough, an inevitability that may well haunt Curtis at night. As it should us

But right away it's clear that Curtis isn't hypothesizing about a terrifying future, but unearthing the hidden patterns that have created the present moment. The villains are not machines. Curtis trips backward, as is his wont, to the '50s and the rise of Ayn Rand, whose Objectivist creed in turn gave fitful birth to a spate of influential ideologies, all of which decided that both nature and human society were essentially self-sustaining, equilibrium-seeking logical mechanisms, and could be managed thus. "This is the story," Curtis intones, "of the rise of the dream of the self-organizing system, and the strange machine fantasy of nature that underpins it." The tales he tells to illustrate this harrowing and almost completely overlooked social saga all intertwine, and run from the "spaceship Earth" ideas of Buckminster Fuller, the communes that followed, the pessimistic forecasts of the Club of Rome, the rise and fall of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo, the genesis of the wholly fabricated Tutsi-Hutu dichotomy that turned Rwanda into a killing field more than once, the career of Dian Fossey, the late-century rollercoaster of economic feast and famine, and the work of theorist/geneticist George Price, who believed that humans were ultimately the slaves of their own genetic imperatives, and who demonstrated mathematically that both altruism and genocide were therefore rational acts, from "a gene's eye view" of things.

There's more, all of it reflecting back upon now; Curtis is nothing if not a staunch proselytizer for the idea of the past never being quite past. All Watched Over is more than a counter-story. Like all of Curtis's work it is approximately half well-circulated history and half "deep" background—that is, storylines and historical angles that have been pervasively and deliberately neglected by the gatekeepers of knowledge and information. The film feels something like a Craig Baldwin delusion-farce turned chillingly, menacingly factual, and the facts accrete into an interrogation of psychotic hubris. The Frankenstein monster constructed by the scientists and demagogues and politicians in All Watched Over is the last half-century or so of life on Earth, which in its ultimate tally amounts to a scoresheet of unimaginable injustice, mountains of bodies, and untold environmental ruin.

Curtis is in reality telling just one story, again and again in various threads and tangents and in dazzling three- or four-hour chunks, reaching back to the immediate postwar years and then forward to the present over and over, limning an infinitely complex genogram of our present existence. Ironically, for a history-rewriting filmmaker/producer boxing so much information into evenings of television, Curtis is fierce about the disastrous effects brought about by the artificial and intellectualized imposition of order. He began in his present mode with 1992's Pandora's Box, a massive autopsy on the worldwide cataclysms that unrolled as a result of every kind of postwar effort to systematize, organize, compel, and codify humanity, from Soviet over-industrialization to game-theory Cold War strategies to Keynesian economics to nuclear-power utopianism. Politically, this is a rocket targeted not at the Right per se, but upward, at the power elite, whose perpetual folly in trying to maximize profit and control leads ceaselessly to societal breakdown—a condition very often beside the point for the elite in question, once they've stood to benefit. The Century of the Self(2002) goes all attack-ad on this dynamic, specifically homing in on propagandist/marketing mahatma Edward Bernays, and how he used Freudian psychoanalytic insights to initiate the gold rush of institutionalized thought control—advertising, propaganda, public relations—that could be said to absolutely dominate 20th-century public discourse.

The Century of the Self

Curtis's vision seemed wholly formed at first, despite the fact that he's obviously digging up unknown connections with each new project. But it took the spiral mindquake of 9/11 for Curtis's reverse-engineered prophecies to gain a global profile. The Power of Nightmares (2004) follows the gunpowder trails from the mid-century (uniting Muslim Brotherhood messiah Sayyid Qutb and neocon pope-king Leo Strauss as complementary agents of desolation) to the attacks of 2001, and then maintains that, just as the farcical depiction of the USSR as a global spider kingdom of evil influence is destroyed by direct testimony from CIA agents and a lying Donald Rumsfeld in old news footage, the sudden postulation of Al Qaeda as a terrifying, organized worldwide threat was a manufactured myth used by Western governments and agencies to broaden and tighten their grip on international power systems and the profit to be gained therein.

The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear

It's a chastening, horrifying notion, but even if Curtis pulls out the agitprop stops himself (his way with menacing dramatic music complements Michael Moore's comic use of pop song montages), you'd be foolish to dismiss him. If Al Qaeda eventually appeared to be less of a myth than he'd maintained, the reason why scans like another Adam Curtis scenario: Bush II's efforts to instill fear, demonize Muslims and take over Iraq simply created the blowback of massive Al Qaeda recruitment and the creation of ad hoc Al Qaeda affiliates, a cold fact explicated since by piles of research-filthy books, Pentagon reports, and declassified State Department releases. Power exerts pressure on the masses, due to heedless institutional gluttony or blind intellectual vanity or both, and shit comes out the other end. The power, meanwhile, persists.Critic J. Hoberman pegged Curtis in a sense when he suggested that his worldview was closer to DeLillo than Chomsky—if we can first take another moment to reflect on the oddity of those choices, that spectrum, in an office at the BBC. True enough, Curtis's corpus has the seething, portentous air of science fiction, without being fictional, and the disconnect there suggests a new kind of culture that may well be a natural byproduct of the postwar era's steamrolling power structures, capitalistic need for growth, ecological devastation, and extra-human technology. Why should the old categories of history, science fiction, journalistic truth, conspiracism and apocalyptic vision retain their mutual exclusivity, as the conceptual barriers between news and entertainment, reality and virtuality, government and corporation, national and global, all vanish like stray broadcast signals? For many of us, a lot of Curtis's historical weaves are a fiction-free science fiction, a massive grid of Orwellian-Dickian-Casolaroesque intimations and eruptions that reveals a nascent totalitarianism spreading like a mushroom colony beneath the surface of everything we see and hear—all of which, of course, is devised and programmed by corporations and governments. If you don't think things have gotten radically different and substantially worse, then you don't, like most people, remember anything significant about the way life was before. As it is, observers who know firsthand about how society chugged, climbed, and conceived of itself before World War II, before Bernays, before the invention of the computer, before the International Monetary Fund, are becoming fewer every year. Attrition will guarantee the absence of informed and memoried resistance soon enough, an inevitability that may well haunt Curtis at night. As it should us

Negotiating the Pleasure Principle: The Recent Work of Adam Curtis

From Film Quarterly, Fall 2008 (Vol. 62, No. 1). — J.R.

There’s been a steady improvement over the course of the three most recent BBC miniseries of Adam Curtis – The Century of the Self (2002, four hour-long episodes), The Power of Nightmares: The Rise of the Politics of Fear (2004, three hour-long episodes), and The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom (2007, three hour-long episodes) —- both in terms of their intellectual cogency and persuasiveness and in terms of the interest of Curtis’s developing, innovative style of filmmaking. One might even contend that each remarkable series has been twice as good as its predecessor. Even so, a closer look at Curtis’s filmmaking style starts to raise a few questions about both the arguments themselves and the way that he propounds them. (Regarding Curtis’s earlier TV series — such as the 1992 Pandora’s Box and the 1999 The Mayfair Set, which I’ve only sampled, and won’t be discussing here —- one can already see some of the thematic and stylistic seeds of his more recent work there.)

I’m certainly not the first one to address these issues arising out of Curtis’s work. Among my predecessors, I’ve been especially impressed by the arguments of Paul Myerscough (“The Flow,” London Review of Books, 5 April 2007, Vol. 29 No. 7) and those of the late Paul Arthur (“Adam Curtis’s Nightmare Factory: A British Documentarian Declares War on the `War on Terror,’” Cineaste, Winter 2007, Vol. XXXIII No. 1). Starting off with a discussion of televisual “flow” as described by Raymond Williams in 1973, Myerscough voices some misgivings about sensual overkill as well as intellectual shortcuts and simplifications, concluding at one point that “I find myself more worried by his documentaries when I go along with them than when I don’t.” Arthur expresses comparable doubts while interrogating some of Curtis’s intellectual arguments in greater detail, and also explores the possible relevance of the neo-Marxism of Curtis’s former schoolmates Jon King and Andy Gill, founders of the postpunk band Gang of Four.

The theses of all three of Curtis’s series are clearly interconnected. The Century of the Self sketches the appropriation of Freud’s theory of the unconscious as a consumerist model for manipulating people economically and politically through their unconscious desires — initially by Freud’s American nephew Edward L. Bernays, the inventor of “public relations,” and subsequently by Gallup polls, Anna Freud’s gospel of social conformity, the “Human Potential” movement that tried to overthrow Anna Freud’s principles of social conditioning, and the eventual development of focus groups in both the U.S. and the U.K. to sell products, including such political candidates as Reagan, Clinton, Thatcher, and Blair.

The Power of Nightmares offers a parallel history of militant Islamism as spearheaded

by Sayyid Qutb and neo-conservatism as spearheaded by Leo Strauss to trace the

development of a political trend in which fear of manufactured and largely imaginary

threats have gradually replaced utopian promises of happiness. This culminates in Curtis’s

most controversial claim in any of these three miniseries —- that the existence of the

terrorist network Al Qaeda is primarily a fiction that was invented in 2001 as a means of

consolidating power.

The Trap to some extent subsumes and extends both of the arguments in the preceding series by maintaining that the Western idea of freedom has been reformulated over the past half-century or so from political freedom to economic freedom (viewed as spending power), again with disastrous results. Basic to this overarching ideological shift is the conviction — promulgated largely by game theorists as a way of explaining the dynamics of the Cold War, and eventually taken up by economists and politicians–that human beings are fundamentally selfish, suspicious, and isolated from one another; that notions of collective will can’t even be theorized according to the new, market-driven models; and that success and happiness are ultimately measurable in numbers rather than in terms of the quality of whatever is being quantified. Here the major villains often seem to be not George W. Bush —- even though he does get a characteristically inane sound bite (“I believe that the future of mankind is freedom”) in the prologue to the first two parts — but Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, for being elected on liberal/labor platforms and then immediately giving away their hard-won power to the banks and markets, meanwhile increasing class inequality in relation to everything from career opportunities to life expectancies in both the U.S. and the U.S. But more generally, what gets vigorously castigated here are irresponsible forms and applications of social science, especially psychiatry, spurred by various forms of capitalism and the numbers game.

A withering examples of the latter, offered in part two of The Trap, “The Lonely Robot,” is the way in which normal human reactions such as fear, loneliness, and sadness were redefined as medical disorders in order to sell newly developed drugs such as Prozac and create new forms of social management. My own tragicomic favorite is one of the many grotesque consequences of the performance targets that followed Blair’s election in 1997: when the government’s aim was to reduce the number of hospital patients who had to wait in corridors on trolleys before receiving care, some hospitals would remove wheels from their trolleys and reclassify them as beds, meanwhile reclassifying some corridors as wards.

In all three of these miniseries, one can trace a certain Hegelian convergence of disciplines and theories that becomes all the more ambiguous, exhilarating, and unsettling once one starts to realize that this convergence is part of Curtis’s own methodology as well as his ostensible subject. In other words, I’m continually being won over by grand explanations for most of our contemporary problems, all of which entail other and presumably lesser minds having been similarly seduced; what might more generally be termed the Eureka mentality is thus posited as both the disease and the diagnosis.

I’m reminded of the most stimulating by far of all the university courses I ever took —- a Bard College seminar taught by Heinrich Blücher, the husband of Hannah Arendt, called “Metaphysical Concepts of History and Their Manifestations in Political Reality”. Blücher, a former German Communist who never published a word, is lamentably overlooked by many people who didn’t know him personally, yet his impact on friends and students as well as on Arendt (who dedicated her Origins of Totalitarianism to him) is irrefutable. The dialectical subject as well as the dialectical methodology of his seminar, which focused on such figures as Hegel, Nietzsche, Spengler, Marx, and Freud, grew out of the various seductions and dangers of all-purpose explanations. Virtually every lecture Blücher gave in the seminar described an arc that climbed towards fervent belief before descending towards skepticism. For better and for worse, Curtis’s audiovisual arguments tend to move in the reverse direction; they all start very promisingly by tearing down some of the ruling myths of our era, and then arguably conclude in far too satisfying a fashion by implying that once we can shatter those myths, we’re almost as wised up as we need to be.

Nevertheless, the value of all three works isn’t just the strength of their arguments but the overall freshness and pertinence of part of the information they impart. Speaking for myself, I was less excited by The Century of the Self because I’d already read Larry Tye’s The Father of Spin: Edward L Bernays & The Birth of Public Relations (New York: Crown Publishers, 1998) — a book whose revelations for me started in its Preface, which explains how the “public relations triumph” that was the “selling of America on the Persian Gulf War…was crafted by one of America’s biggest public relations firms, Hill and Knowlton, in a campaign bought and paid for by rich Kuwaitis who were Saddam’s archenemies.”

If memory serves, this tidbit is missing from The Century of the Self (although Tye is one of the people interviewed), but the material imparted about Bernays and his legacy — starting with his own coinage of the term “public relations” as a euphemism for propaganda —- is pointed, well chosen, and instructive. (One particular gem in Part 2, “The Engineering of Consent,” is the story of how housewives were coerced into buying Betty Crocker cake mix once their egos were stroked by the gratuitous instruction that they add one egg to the mix.) And some of it overlaps neatly with material discussed in Naomi Klein’s magisterial The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), a book whose own clarifying synthesis of information seems comparable and complementary to some of Curtis’s best insights.

I’m thinking in particular of the terrifying exploits of Dr. Ewan Cameron, whose CIA-funded employments of LSD, PCP, and electroshock to hapless patients begin Klein’s narrative and are pointedly referenced by Curtis. One might also note that her postulation of Milton Friedman as a guru from hell essentially “rhymes” with Curtis’s uses of Bernays in The Century of the Self, Strauss in The Power of Nightmares, and even Isaiah Berlin and his concept of “negative liberty” in part three of The Trap, “We Will Force You To be Free”. Indeed, in the closing stretches of the latter, when Curtis is critiquing the disastrously misguided and theoretically driven employments of “shock therapy” in postcommunist Russia and, more recently, in Iraq, his arguments seem to coincide fairly precisely with those of Klein. (Another film with certain conceptual parallels to Curtis’s three series is Mark Achbar, Jennifer Abbott, and Joel Bakan’s excellent 2003 documentary The Corporation.)

***

The developing style of Curtis’s essayistic documentaries is to alternate talking-head interviews with diverse kinds of found footage, the latter sometimes overlaid by music drawn from Hollywood films. Some of the scores borrowed in The Power of Nightmares come from John Carpenter’s Halloween and Prince of Darkness, The Ipcress File, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, two Morricone-scored Italian pictures, and Neptune’s Daughter —- the last of these being the source for Johnny Mercer’s “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” which dominates the first episode. And especially memorable in The Trap are Bernard Herrmann themes from films by Welles and Hitchcock —- a ploy that periodically becomes distracting, perhaps even more so if one is conscious of where they’re coming from. I’m not sure how helpful it is, for instance, for the sprightly chase music from North by Northwest to accompany Curtis’s aforementioned discussion of performance targets in Blair’s version of New Labour and — more briefly later on — his discussion of Franz Fanon and Jean-Paul Sartre’s espousals of violence in third-world revolutions. Whatever postmodern ironies Curtis might have in mind with these juxtapositions, they really don’t add much to the discussion.

The fact that Curtis hasn’t acquired rights to either the clips or the music is largely what accounts for them not being better known outside the U.K., although all three series are readily accessible via the Internet for those who go looking for them. (In the U.S., the three parts of The Power of Nightmares, the best known of the three series, have become available in issues #2, #3, and #4 of Wholphin, a DVD magazine issued by McSweeney’s and available in some bookstores as well as through outlets such as Amazon.)

There seem to be at least three major issues worth addressing about these miniseries. The first is the validity of the intellectual arguments they propound. The second is the validity of the anti-intellectual methodologies they sometimes employ in terms of sound and image, in which the clips and music serve not so much to illustrate the arguments as to weave fanciful and seductive arabesques around them. (These are far more evident in the latter two series, although The Century of the Self already suggests this practice when it suddenly intercuts details from 1929 with tracking shots through opulent, apparently Viennese settings that suggest color versions of shots from Last Year at Marienbad.) And the third is the seeming incompatibility of these intellectual and anti-intellectual elements, complicated by the fact that the anti-intellectual elements at times seem to resemble the advertising techniques that are being critically addressed throughout the series, which appeal to unconscious desires more than to conscious and rational formulations.

Given how much the polemical agendas of these three series are bound up with the way that apparently rational intellectual positions can eventually lead to irrational and delusional conclusions, there’s a great deal at stake in determining how much intellectual honesty Curtis should be credited with as a filmmaker and not simply as a thinker delivering a voiceover. To all appearances, his voiceover remains serious while his filmmaking periodically oscillates between a serious (that is, rational and readily explicable) illustration of his arguments and fanciful, free-form riffs sailing over the arguments, a bit like jazz improvisations. (There are also some images that might be described as both serious and playful, e.g., the recurring image of red paint being poured over a globe of the world in “The Phantom Victory,” part two of The Power of Nightmares— a Cold War metaphor with a certain amount of mockery in its literalism, but none the less a relatively coherent kind of representation.) And just as jazz solos are typically predicated on following the chords of pre-existing melodies, Curtis’s riffs loosely follow the contours of his voiceover arguments that are being heard simultaneously, without being answerable to a comparable linear logic of continuity except by implication.

The issue isn’t whether or not the playful improvs are acceptable in their own right. I believe they are, or at least they can be, and on my website (www.jonathanrosenbaum.com) I recently wrote a brief defense of a lively DVD extra — Jean-Pierre Gorin’s “A ‘Pierrot’ Primer” on the Criterion release of Godard’s Pierrot le fou —- that has comparable strengths and limitations. My point there is that once criticism is viewed as a performative act occurring over a fixed period of time, our means of judging such acts can’t and shouldn’t be precisely the same as the way we regard criticism in print. “The truth is, you cannot hang an event on the wall, only a picture,” Mary McCarthy once wrote, in a favorable 1959 review of The Tradition of the New by Harold Rosenberg, the theoretician of action painting (“An Academy of Risk,” in McCarthy’s On the Contrary: Articles of Belief, 1946-1961, New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1961, p. 248) —- thus pinpointing part of the ontological difficulty posed by performative criticism, where “scoring points” no longer means quite the same thing, existentially speaking, which implies that somewhat different criteria of evaluation may be needed.

Admittedly, even this distinction becomes somewhat problematical as soon as we consider that there are certain instances of print criticism that might be said to function according to performative models. The sole example of the latter that I cited on my website was Manny Farber, although I could have also mentioned the critical prose of several other reviewers, ranging from Godard to Pauline Kael to Manohla Dargis. The only way of resolving this seeming contradiction, I would argue, is that we know and acknowledge what kind of critical discourse we’re responding to. And this becomes harder to do when we’re confronted with two kinds at once, as we often are in Curtis’s televisual discourse.

***

I’m not trying to propound the Marshall McLuhan argument here that the medium is necessarily the message. The point of contention here is journalistic shorthand, which exists both in print and in broadcast media and often entails some difference in meaning and content as well as style. Theoretically speaking, insofar as montages are extensions of the Kuleshov Experiment in which the viewer unconsciously connects certain shots by furnishing them with imagined fictional links, the very act of editing these shots together becomes a form of lying. Therefore the juxtaposition of found materials, including the use of Hollywood scores on the soundtracks of Curtis documentaries, might be said to function as vehicles of persuasion —- ploys for helping us to accept the voiceovers but not really legitimate parts of the ongoing argument. Whether we identify these ploys as placebos or as less deceptive vehicles of pleasure is the main issue at stake. Quite apart from Curtis’s use of such rhetorical tricks in his narration as unjustifiably describing his own arguments as if they were conclusive demonstrations (as pointed out by both Myerscough and Arthur), there’s the broader and somewhat less obvious tactic of making them pleasurable to watch —- fun and therefore easy to swallow —- as if they were TV commercials.

Most of the footage in The Power of Nightmares conventionally illustrates Curtis’s voiceovers. Yet all three episodes begin with a free-form montage accompanying his narration that’s so open-ended it becomes impossible to identify what one’s watching, while additional sounds (a howling wind and periodic stabs of percussive music) increase the overall dreamlike effect. All proportions guarded, it’s a bit like the difference in exposition between the enigmatic prologue of Citizen Kane and the “News on the March” that follows it, with the crucial difference that Curtis uses a voiceover in both segments.

Consider just the first four sentences and the accompanying images: Initially we see what appear to be blinking bright lights on an airstrip over the sound of the wind. Then, as Curtis says, “In the past, politicians promised to create a better world. [Music starts.]. They had different ways of achieving this, but their power and authority came from the optimistic visions they offered their people,” we’re treated to rapid, disorienting, continuous camera movements in a dark and ambiguous space where people are fleetingly glimpsed in the background that eventually becomes, behind the BBC logo, an empty and overlit TV studio anchor space with a shifting backdrop that’s gripped from behind by visible fingers. Then, while Curtis continues, “Those dreams failed and today people have lost faith in ideologies. Increasingly, politicians are seen simply as managers of public life, but now they have discovered a new role that restores their power and authority,” we get a burst of TV static, another camera movement traversing an indecipherable flash of orange and yellow, a static shot of an ornate chandelier with fading lights (or is it a fadeout in a shot of a chandelier that remains lit?), and then high-contrast black and white footage of a nighttime, flag-strewn political rally that could conceivably be a clip from Eisenstein or Pudovkin. In short, you might say that Curtis is restoring power and authority to his own voice while tossing us into an intractable labyrinth.

***

If I can be permitted a couple of extended, autobiographical illustrations of comparably pleasurable media tricks, I can say that, like many others, I’ve benefited as well as suffered from the kinds of routine distortions practiced by these methods. In the mid-70s, while living in London, I was once interviewed on BBC radio about Robert Altman’s innovative employments of sound in conjunction with an Altman retrospective at the National Film Theatre that I had just helped to organize. It seemed appropriate to offer an analysis of a particular extract from the soundtrack of California Split, so I was mortified to discover when I heard the broadcast that the producer had chosen a different and much simpler extract to illustrate the point I was trying to make —- with the result that my analysis sounded to me both inane and inaccurate. But when I phoned her to complain, she argued that editing fixes of this kind were standard and that I was naïve to raise any fuss about them.

By way of contrast, the way I’m used to deliver the climactic thesis of the feature-length documentary Hollywoodism: Jews, Movies, and the American Dream (Simcha Jacobovici, 1997) — that the American Dream as articulated by Hollywood was fundamentally a Jewish invention — is no less sinister, at least in its implications, even though this time I was seemingly boosted rather than undermined by the misrepresentation. Indeed, my talking head is positioned so that the entire thrust of the film’s preceding argument —- actually the argument of Neal Gabler’s first-rate and provocative book An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, which this film is adapting – appears to be emanating spontaneously from my lips, when I say, “There was a Hollywoodism then, there is a Hollywoodism today. I would go further and say it is what is the ruling ideology of our culture. Hollywood culture is the dominant culture; it is the fantasy structure that we’re living inside.” None of which I exactly disbelieve. But the ugly and awkward coinage “Hollywoodism,” used as a derivation of “Americanism” — which doesn’t even figure in Gabler’s book — would never have passed my own lips if the interviewer hadn’t planted it there. If memory serves, all I was doing at that point was agreeing with some rough paraphrase of Gabler’s thesis that the unheard and unseen interviewer had offered, meanwhile hoping that the modest personal contribution I’d made to the discussion — about the ways my grandfather, a small-town movie exhibitor, shared many of the values of the studio moguls discussed by Gabler —- would be used in the film. (It wasn’t.) Nevertheless, an old friend of mine, a professional writer of TV documentaries himself, told me that he concluded at the end of Hollywoodism that its overall message, including the coinage of its title, was somehow my own invention.

Such are the everyday, routine spinoffs of the Kuleshov effect in most documentaries employing taking heads and clips. In the same documentary, the same sort of leveling effect allows archival footage of European shtetls to casually rub shoulders with a musical number from Fiddler on the Roof, and virtually equates the veracity of black and white newsreel footage of HUAC hearings with the authenticity of color extracts from a representation of those hearings in Irwin Winkler’s idiotic and reprehensible Guilty by Suspicion.

In an interview with Robert Koehler in Cinema Scope no. 23 (summer 2005), Curtis defends the practice of his own playful montages as follows: “I don’t see why you can’t play with pictures when you’re being serious. That’s my main aim. Because then you get a sense of someone enjoying themselves, and when you get that, then people listen to what you’re doing.” And I suppose a related argument could be made about some of the more ambiguous procedures in Craig Baldwin’s experimental documentaries —- Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1991), ¡O No Coronado! (1992), Sonic Outlaws (1995), and Spectres of the Spectrum (1999) — which simultaneously mock and indulge in paranoid rants while dovetailing as many technological conspiracy theories as possible.

There’s something appealing about leaving the overall degree of seriousness behind the arguments up to the viewer, but there’s also a calculated risk. Even though Curtis’s arguments register much more seriously than Baldwin’s, both filmmakers seem to be operating at times with built-in escape clauses. But how many people who watch television are thinking much about the play or, for that matter, the personality of the filmmakers as reflected in such creative decisions?

It’s worth adding that Curtis himself speaks the voiceovers in these series, but never uses the word “I”– even though the arguments are always clearly his own, and when we hear the offscreen questions being asked in various onscreen interviews, it’s invariably his voice that’s asking them. His overall stance is neither that of the traditional voice-of-God narrator nor that of an essayistic filmmaker like Chris Marker who, in Sans Soleil (1982), feels that his speaking voice has to be filtered through one or more fictional intermediaries in order to achieve the kind of guarded intimacy that he wants. But Curtis sounds closer to the voice-of-God narrator insofar as he’s banking on the appearance if not the fact of conventional television. And it’s finally this appearance that makes his work so debatable as well as innovative. Whether or not this is part of his intention (and I suspect it isn’t), Curtis is foregrounding some of the double standards that many of us bring to criticism in separate media simply by banking on them.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar