Louis Feuillade je između 1906. i 1924. snimio 630 filmova, a samo Tih-Minh traje 7 sati. Les Vampires također, pa serijali Fantômas, Judex itd. Kad bi sada još Bill Morrison sve to malo distorzirao i pretvorio u nepoznat Proustov film.

Canons form based on availability. This is notoriously true for literature, where translation helps determine who gets to read what, and when—just think of the fervor with which the American literary establishment has greeted W.G. Sebald and Roberto Bolaño novels over the past 20 years once their work has been translated, well after the authors' books were celebrated back home in their original languages. But lack of access also haunts cinema studies, often for equally transnational reasons. Many movies don't cross the pond. Foreign cinema currently accounts for less than five percent of all movies released theatrically in America, so the problem is especially true now. It's also true for repertory—DVD can only account for so much. Jean-Pierre Melville, the great French crime director whose 1969 French Resistance film Army of Shadows received its stateside theatrical premiere a few years ago and was acclaimed by many critics as the best release of 2006, is a recent discovery for most American cinephiles. The Portuguese Pedro Costa, who may be the world's greatest filmmaker age 50 or younger, is a discovery-in-progress. Louis Feuillade (pronounced "Foy-yad"), the brilliant French silent film director without whom Surrealism might never have flourished, has barely been discovered at all.

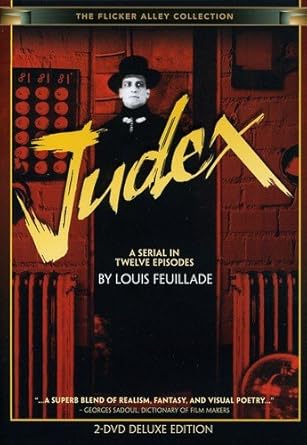

Feuillade directed films from 1906 to 1924, the year before his death. He has one high-profile, universally acclaimed crime thriller, 1915's Les Vampires, available on DVD in the States, as well as another, less-acclaimed but also brilliant policier (1916's Judex) and a series of about 10 shorts on an omnibus silent film box set released by the famed French studio Gaumont. This seems like ample representation, until one realizes that Feuillade made more than 600 films in his career (IMDb counts 633). Even though many of his films were 20 minutes or shorter, this is a stunning level of productivity. Feuillade is all the more impressive for working so voluminously even during WWI. Yet despite so many credits, few American moviegoers know Feuillade. Senses of Cinema lists over 200 entries in its Great Directors section, but lacks a Feuillade page; by contrast, the Ken Russell and Craig Baldwin entries seem pretty complete.

Many of Feuillade's films were lost or destroyed during World War II. I'm not qualified to comment on rights issues, but I can still cite three further reasons why American audiences haven't seen more of Feullade's work:

1. Format: Calling Feuillade's most revered films features is stretching the term some. He was more properly a film serial director, a tradition which sprung out of the 19th-century newspaper tradition of serializing stories over weeks or even months (if the film serial's precedent was the newspaper serial, its descendant has been the TV miniseries). In contrast to most feature films, in which a self-contained story unfolds over a block of time meant to be experienced in one viewing, Feuillade made multi-part films whose installments came out theatrically in subsequent order, building momentum each week. You can think of Les Vampires and Judex as long films, or as a series of short films—for instance, Les Vampires has 10 parts. Back when cinema was the main popular entertainment, asking a large audience to come out to the movie theater over 10 consecutive weeks was reasonable; nowadays, it would be suicide. This is just as well since, like Béla Tarr's 1994 film Satántángó, another long-form, multi-piece work, the parts form a cogent whole when shown together. But projecting the entirety of a Feuillade serial creates another problem.

2. Length: With all the parts added together, it's common for an entire Feuillade serial to run six to eight hours. As Richard Maxwell has noted, the tradition of showing Feuillade's serials in their entirety in the United States began in the 1970s, around the time when artists like Robert LaPlage, Robert Wilson, and Philip Glass began conducting long-form experiments in music and theater. Yet the problems such works face in finding an audience now seem self-evident.

3. Silence: Because they were made on cheap, easily flammable and/or disintegrating film stock, most silent films are lost to us today (in the United States alone it's been estimated that 75 percent of silent films are irretrievable). Because they're so rare, audiences are not used to them, and tend to be apprehensive. I don't mean that audiences don't like silent movies—I mean that they're unwilling even to watch them.For over 90 years 1913's Juve vs. Fantômas was the only Feuillade film circulating theatrically in the States. Even the Feuillade work currently known and available is so largely because of more recent remakes and adaptations—the French filmmaker Georges Franju (Eyes Without a Face) remade Judex in 1963, and Olivier Assayas made Irma Vep, a Maggie Cheung-starring comedy about a film crew remaking Les Vampires, in 1996. But many of the audiences that have seen Judex and Les Vampires don't know about Feuillade's other great work, such as 1914's Fantômas, 1919's Barrabas, and perhaps most supremely, 1918's Tih Minh.

The critic Jonathan Rosenbaum considers Tih Minh one of his 100 favorite movies, thinks it is better than Les Vampires, and, in his book Midnight Movies, calls it the perfect late-night attraction, even with a 357-minute running time. Yet the Internet Movie Database lists no reviews of the film whatsoever, nor anything so much as a plot summary; ditto for Tih Minh's Wikipedia page.

Tih Minh prints are hard to find. The Cinématheque Francaise owns one, as does Anthology Film Archives, but public screenings rarely happen. I was thus fortunate to catch a screening recently at a Yale conference, spearheaded by History of Art and Film Studies graduate student Richard Suchenski, called "After the Great War: European Film in 1919." The conference also showed rare treats like Abel Gance's J'Accuse and Ernst Lubitsch's The Oyster Princess (The Auteurs's Daniel Kasman remarked that, had it played in New York, the conference would have been the city's best repertory series of 2009), but opened with Feuillade. Suchenski's program notes read that "Although Tih Minh was a great success during its initial release, it was never translated for export and circulated only in incomplete or damaged prints for decades." After years spent hoping to see Tih Minh, I found it more than worth the wait.

The film begins with explorer Jacques d'Athys (René Cresté) returning home to his family from Indochina. He brings along Tih Minh (Mary Harald), a lovely young girl that he picked up in Laos. He and his loyal servant Placide (Georges Biscot) soon involve themselves in international intrigue that includes jewel thieves-cum-spies who render their victims amnesiacs, a treasure map written in an ancient Asian hand, a literally hypnotic Hindu villain, an insane asylum, and a rock avalanche. A character declares, "Understand that I have to avenge the death of my father." In the midst of the madness Tih Minh herself becomes a structuring principle, as many of the film's 12 episodes involve the villains kidnapping her and her subsequent escape or rescue. As the serial's first third concludes, our heroes flee from the villains, their lovely T.M. in tow; the second third ends with the villains fleeing from them; and the last four episodes build to a final, deadly mountaintop confrontation between the two groups.

The movie doesn't have a plot so much as a list of incidents. I don't feel like I've given much away, since the one-damn-thing-after-another structure keeps the viewer watching more for what happens moment to moment than for where the story's going overall. As a consequence of its cliffhangers, and despite its length, Tih Minh zips. In an April 1999 Sight & Sound piece on Feuillade, Vicki Callahan wrote that "the serial form means that the pursuit of criminality or evil is essentially an ongoing saga that can never be completed; the capture of the criminal is not a moment of closure but rather an opportunity to start the narrative anew, since capture is invariably, and sometimes immediately, followed by escape. Rather than a linear, goal-oriented story we have a narrative loop, and one that is further complicated by character movements (whether through misidentification or a particular character's ethical transformation) between the criminal and law-abiding roles."

As Callahan points out, Tih Minh's characters frequently tend to shape-shift and role-play, both through external and internal activity (disguise is one example of the first, hypnotism of the second—misidentification is common in the film, though ethical transformation is scarce). In one scene Tih Minh and Placide's maid fiancée Rosette (Jeanne Rollette) are visited by a pair of nuns at their home, the Villa Luciola. One of the nuns soon throws off the habit, revealing herself to be the villainous male thief, Kistna (Louis Leubel). Brandishing a pistol, Kistna leads Tih Minh out into the garden to find a map for him; he fires his gun, and the bullet ricochets against a statue and wounds him in the hand. At this point Placide (who's discovered the hidden microphones) bursts into the frame and, chasing Kistna with a powerful hose, drives him over the garden fence. The sequence mimics the film's overall power struggle—from good, to evil, to a restoration of the good. In the next episode Kistna will send a spying maid and her equally spying dog to infiltrate the Luciola gang, but that too will pass. Like a Shakespearean comedy, Tih Minh moves from chaos to a restoration of order. The film even marches toward a traditional comedic ending—d'Athys and Placide plan a double-wedding for when all the chases are done.

Feuillade is able to depict such wild happenings onscreen because his foundations are so solid. I mean this not just from a storytelling perspective, but from a visual one. The director consistently relies on static medium-to-establishing shots, proscenium-like in their orientation, the camera viewing the characters from a slightly elevated angle, and the lighting's generally unobtrusive. In other words, Feuillade gives us a relatively normal, stable-looking frame so that the odd happenings within it can seem all the more disruptive.

Some of these moments are indomitably striking, especially in the film's first few episodes. Dreaming of the abducted Tih Minh, d'Athys envisions a ghostly superimposition of her, white dress billowing over waves. Later, upon breaking into the spies' memorably-named Villa Circé to look for her, d'Athys and Placide stumble across a basement room and swing the door open. Inside they see hundreds of women, their hair wild, eyes wide, and white dresses soiled, crawling over each other, the only ray of light beaming in from a barred window above. The men begin searching for Tih Minh, but cannot find her. Meanwhile, the women crawl out and, arms forward, zombie-like, begin wandering the island.

The film frequently invokes mental health—both good and bad doctors lead people into forgetting and remembering their pasts, or inventing new ones, and at one point a key character is even mistakenly locked up in an insane asylum, the plot unable to advance until his release. Freud's burgeoning theories of psychoanalysis hover about the film (while the 63 year-old Freud had yet to write major works like Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Civilization and Its Discontents at the time of Tih Minh's release, The Interpretation of Dreams had been in print for almost 20 years). So, too, does World War I: The Armistice was signed November 11th, 1918; Tih Minh's first episode premiered theatrically on November 30th. The references to the unnamed conflicting governments for whom the characters work recall the convoluted alliances countries formed and broke with each other during the Great War, but the lingering sense of devastation and trauma that the war left across Europe floats through the movie as well.

Feuillade is filming a rousing adventure story, but he's also questioning the future of the world. It's a world explicitly without central authority figures, in which the characters fight to assert their own moral order—as one of d'Athys's companions conveniently says late in the film to justify hunting the thieves, "why inform the police? We are mixed up in the most remarkable adventure in the world, let's go all the way with it ourselves." To show how free society hangs in the balance between poles of good and evil, Feuillade doubles many opposing characters. D'Athys's friend, the good Doctor Davesne, is mirrored by the chief spy Doctor Gilson. Rosette, the good maid, faces an evil maid as her counterpart. Tih Minh breaks out of the spell Gilson and Kistna have put her under, while Gilson's henchwoman Dolores confesses everything to Davesne under hypnosis. Kistna and his servant Fritz ultimately betray each other, while d'Athys and Placide stay true to one another (all the performers portray effective archetypes, but Biscot's comic servant is especially wonderful—as he charges gallantly forward to save the women from harm, his flat eyes and smushed face make him seem like a more adult Stan Laurel, though equally, sweetly monstrous). Tih Minh and Kistna show the good and bad possibilities of Europe mixing with Asia.

The film balances its societal poles so that Nature ultimately has to intervene. Toward the end of the film, as the felons flee into the mountains, Feuillade moves his camera several hundred feet back and we see them as specks in the landscape. Unlike Les Vampires, in which the black-clad Irma Vep appears and disappears at her liking, the antagonists here never seem more than human; once the boulders crash, they seem especially so. D'Athys, a bland hero, triumphs over his adversaries not through skill so much as through luck and fate. Rather than a screenplay deficiency, this seems the movie's point.

I wrote earlier that modern audiences are unused to watching silent films, but other silent cinema isn't the right point of comparison for Feuillade's work. Les Vampires came out the same year as The Birth of a Nation, but as Jonathan Rosenbaum writes, Griffith and Feuillade "seem to belong to different centuries. While Griffith's work reeks of Victorian morality and nostalgia for the mid-19th century, Feuillade looks ahead to the global paranoia, conspiratorial intrigues, and SF technological fantasies of the current century, right up to today."

The most appropriate comparison for Tih Minh isn't to another silent film, but to a recent hit like The Dark Knight. Both films are about shape-shifting, disguise-donning villains and the heroes who take the law into their own hands to stop them. Both films structure themselves as a series of setpieces alternating between each party's capture and escape. Both films are allegories about the wars their countries were then fighting (Tih Minh's gang is a gaggle of foreigners; several Dark Knight characters call the Joker a terrorist).

Yet Tih Minh trumps The Dark Knight stylistically, tonally, and thematically. Christopher Nolan edits his movie to death, rendering a car chase indecipherable; Feuillade respects the laws of physical space, so that when characters chase each other on ski lifts, a thousand feet off the ground, we still sense where they are in relation to each other and what they have to do to catch up. Nolan pounds his points home with glum, dark seriousness while simultaneously asking us to believe in a clown who can stuff a bomb into a fat man's chest when no one's looking; Feuillade knows a poisoned potion in the wine is improbable, and has Placide switch it with sugared water. The Dark Knight insists that wire-tapping, torture, and government cover-ups are necessary in the name of freedom, accepting these precepts fatalistically; Tih Minh, by contrast, shows us a world worth saving. I never want to see Nolan's movie again, but while Feuillade's film is almost triple its length, I feel I could watch Tih Minh at least 30 more times. One film exhausts, the other liberates; the comic book film thinks it's addressing reality, but the human film knows it speaks the language of dreams.

Aaron Cutler www.slantmagazine.com/house/2009/12/the-treasure-of-tih-minh/

The Innovators 1910-1920: Detailing The Impossible

When Louis Feuillade first began to make crime serials he was vilified. But 'Fantômas' and 'Les Vampires' began a rich tradition of questioning narrative certainty, argues Vicki Callahan

Two of the great works of cinema were released in 1915: D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation and Louis Feuillade's Les Vampires, a ten-part film with episodes appearing between November 1915 and June 1916. The disparity in tone and style between these two masterpieces stems not only from their directors' individual visions or the different national contexts in which they were produced. Rather, what these films represent are two distinct modes of cinematic expression and two separate paths for cinema history. If the Griffith film has been taken as a signpost on the way to 'classical' Hollywood or the 'institutional' mode of film-making, the place of Feuillade's Les Vampires is less clear cut.

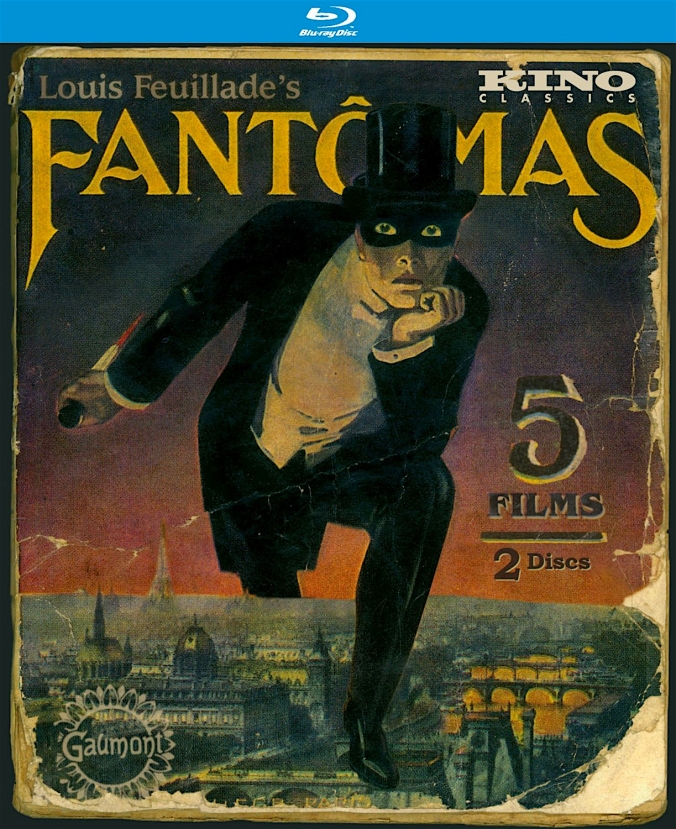

Feuillade's relative absence from the stage of cinema history can be traced to a certain extent to the mixed reception given his films at the time of their release. Born in 1873, Feuillade came to Paris from southern France in 1898 to pursue a career in journalism. His conservative educational background and association with the right-wing press gave little hint of the radically subversive aesthetic that would emerge in his films. He was hired by Gaumont as a scriptwriter in 1905 and in 1907 replaced Alice Guy as head of production. Before leaving Gaumont in 1924 Feuillade made more than 800 films covering almost every contemporary genre: historical drama, comedy, realist drama, melodrama, religious films, and so on. However, he was most famous, or infamous, for his crime serials: Fantômas (1913-14), Les Vampires, Judex (1916), La Nouvelle Mission de Judex (1917), Tih-Minh (1918) and Barrabas (1919).

These films were particularly despised. The crime serial was a popular and prolific genre at the time in both American and French cinema; French precursors to Fantômas include the Eclair company's Nick Carter (1908-10) and Zigomar (1911-13). The five episodes of Fantômas were based on a series of 32 novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre which tracked the exploits of the elusive (insaisissable) eponymous criminal (René Navarre) and his dogged pursuers, the detective Juve (Bréon) and his ally Fandor (Georges Melchior), a journalist. The key term here is elusive - even the final episode in a repeated structure of chase, capture and escape leaves the criminal's fate open-ended.

The production of Les Vampires was initiated when Gaumont learned of the projected release in France of the American film Les Mystères de New York, starring popular serial heroine Pearl White of The Perils of Pauline fame. The structure - based on the pursuit of a criminal gang, the Vampires, by journalist Philippe Guérande (Edouard Mathé) - is similar to that of Fantómas, but here the head of the criminal gang changes with disconcerting frequency (in part, no doubt, because of the difficulty of keeping actors during the war years). The one consistent figure is jewel thief and prototypical femme fatale Irma Vep, portrayed by Musidora.

A typical reaction to these films is that of a critic in Hebdo-Film (22 April 1916): "That a man of talent, an artist, as the director of most of the great films which have been the success and glory of Gaumont, starts again to deal with this unhealthy genre [the crime film], obsolete and condemned by all people of taste, remains for me a real problem." Feuillade's crime films were perceived as old-fashioned and inartistic - unable to boost cinema's status as 'art' or to confer it with bourgeois respectability (which is precisely what endeared them to the Surrealists). The preoccupation of French critics and film-makers in the 1910s and 20s was to elevate cinema, especially French cinema - and the French saw their own films as lacking the artistry and sophistication of Griffith or DeMille - to the level of art. It was years before Feuillade's films escaped the label of aesthetic backwardness, and as a result until recently only a handful of theorists and historians (Richard Abel, No'l Burch, Francis Lacassin, Annette Michelson, Richard Roud) have examined his work closely.

But responsibility for Feuillade's marginal status within film history cannot be placed solely at the doorstep of past critics. Rather, his film style is organised around an aesthetic of uncertainty that makes his work unclassifiable in terms of the categories traditionally applied to silent-era film-making. Early film is usually divided into what historian Tom Gunning has called a "cinema of attractions" and a "cinema of narrative integration". In the former, the spectator is external to the story space, an effect created by tableau staging, long takes and the essential autonomy of each shot. The overall strategy is one of showing: the displaying of events, tricks and scenes rather than the telling of, or immersion in, a story. The 'trick' films of Georges Méliès provide a clear example of this mode of film-making - even a film like Le Voyage dans la lune (1902), with its clear-cut narrative trajectory featuring a group of scientists' journey to the moon and back, foregrounds the spectacle of the trip and the display of adventures along the way rather than the story itself.

Griffith, by contrast - the prime exponent of Gunning's "cinema of narrative integration" - implements cinematic devices (parallel editing, point-of-view shots, close-ups) to draw us into the story space. Film form in this context becomes subordinate to narrative drive - a feature perfected by 'classical' Hollywood to the point where visual style is often said to be 'invisible'. Though Griffith's films may utilise non-continuous elements - moving across space, time and characters - the overall drive is to create a unified sense of space and time, a coherent and cohesive story world. Narrative is not just foregrounded in this process but is a crucial component; it must provide adequate details (character information and depth) and a particular trajectory to enhance the effect. At the end of The Birth of a Nation, for instance, the rescue by the Ku Klux Klan of South Carolina sweetheart Elsie (Lillian Gish) from a forced marriage with black villain of the piece Silas Lynch (George Siegmann) signals the unequivocal defeat of evil and the rescue of Southern 'culture'. President Woodrow Wilson described The Birth of a Nation as "like writing history with lightning" in that the film seared its particular version of history in its audience's and ultimately the national consciousness.

If The Birth of a Nation gives us history written "with lightning", Les Vampires gives us history written by a phantom. Neither a "cinema of attractions" nor a "cinema of narrative integration", Feuillade's films offer us a cinema of fluidity and uncertainty whose operation can be traced to three factors: his investigation of cinema's recording function; the serial narrative form; and his abstraction of the body as the site of cinematic uncertainty.

Feuillade's crime serials oscillate between and reach beyond the "cinema of attractions" and "cinema of narrative integration" models. As in the former, he uses long takes and a stationary camera to create a tableau effect, with title cards often providing the only break between successive, but spatio-temporally consistent, tableaux. In other words, there is a minimum of cut-ins, close-ups or movements between spaces (via the match cut) in his narrative exposition and any cut-ins that do appear are rarely attached to a particular point of view (which would position us within a character's vision and knowledge), functioning rather as a more or less 'objective' insertion of information. This is typically how we are made aware of plot motors such as poison rings, hiding spaces and means of escape.

In a scene from Fantômas, for instance, we see the criminal smash the bottom of a wine bottle in long shot and then cut in to a close-up of the broken area of the bottle. There is no close-up of the character's glance as he surveys the area, though he does appear to turn slightly as if to put the information of the broken bottle on display for the audience. This soon becomes an important detail in the narrative when the criminal escapes the police by hiding in a water tank and breathing with the aid of the broken bottle. This act of display by Fantômas rather than our alignment with his perspective is typical of the "cinema of attractions" elements in Feuillade's film-making. Nonetheless, examples of continuity editing can also be found, and their deployment to link consecutive narrative units would seem to suggest a more unified story space. But the problem becomes what we learn in that story space.

Feuillade's long takes, in conjunction with the deep space of a detailed interior set or a Parisian city space, produce an effect of the real. But this effect is quickly undone. For instance in one of the many abduction sequences in Les Vampires, Philippe Guérande hears a sound at his upstairs window. The first shot of the sequence shows him at work in his office; he hears the noise and goes to the window to investigate its cause. Then, in a match cut, he moves through the window space to look outside, in medium shot (shot 2). Suddenly a noose appears in the shot and pulls Philippe downwards. As he falls we cut to a long shot (shot 3), in a perfect continuity match, in which we see Philippe's fall to his captors. Shot 4 (in medium shot) shows the kidnappers catch their prey (barehanded, no less), again in a continuity match. Every aspect of this impossible fall and catch is tracked for us by the camera in seemingly close detail. The cuts back and forth from medium to long to medium shots facilitate the trick and the substitution of a dummy for part of the fall does not hamper the sheer facticity of the event we have witnessed. The cinema has shown us something that is, in effect, impossible to see. And our faith in cinema's record of the real, and the very relationship between vision and knowledge, are thereby questioned.

As with Griffith's "cinema of narrative integration", the effect of the cinema of uncertainty is produced through the interaction of visual elements and narrative form. While Feuillade's crime films may appear to be consistent with certain narrative conventions - as in Griffith's work it seems clear who is the criminal and who is the force of the law - in fact a number of them play with ambiguities concerning the identity of the real criminal. At one point in Fantômas the detective Juve is suspected of being the master criminal and even has an identifying wound only the real criminal could have (which of course turns out to be a false sign). At another point the criminal's tell-tale disguise - his black bodysuit - is appropriated simultaneously by two other characters as part of police efforts to trap Fantômas at a costume party, so the ensuing chase presents us with three figures dressed identically with no markers as to who should be vanquished. Moreover, the serial form means that the pursuit of criminality or evil is essentially an ongoing saga that can never be completed; the capture of the criminal is not a moment of closure but rather an opportunity to start the narrative anew, since capture is invariably, and sometimes immediately, followed by escape. Rather than a linear, goal-oriented story we have a narrative loop, and one that is further complicated by character movements (whether through misidentification or a particular character's ethical transformation) between the criminal and law-abiding roles.

A similar narrative pattern can be found in Jacques Rivette's Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974). Here the two women, who appear to meet by chance, take turns to recount (repeatedly) a mystery narrative. Each woman inserts herself in the same role within the narrative, but near the end both appear in the mystery-story space simultaneously. And this narrative loop is extended to the larger framing story, since the film ends as it began with the two women meeting by chance again, but with the roles of the encounter reversed. (The film also offers a more direct homage to Feuillade when Céline and Julie rollerskate by in black bodysuits - a reference to Fantômas or an invocation of Musidora/Irma Vep from Les Vampires.)

Like Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, Feuillade's Les Vampires can be read as a historical document. Here the uncertainty within the visual field reflects a larger cultural anxiety - France in 1915 was undergoing enormous cultural, social and technological changes wrought by World War I and the related phenomenon of the so-called new woman. It is no accident that the figure of criminality in Feuillade's two most famous films ostensibly appears the same - the black bodysuit - but changes sex (from male in Fantômas to female in Les Vampires). To put it another way, it is possible to see the body in its plain black casing as a negative screen on which is projected a series of anxieties to do with the cultural upheavals. This abstraction of anxiety is then displaced once more by the substitution of Irma Vep for Fantômas, making sexual difference the site of all differences, all anxieties. In Olivier Assayas' Irma Vep (1996) the fictional director René Vidal recognises that Irma is the central character in his remake of Feuillade's Les Vampires. And much like Musidora, actress Maggie Cheung, who plays herself in the film, becomes a blank screen on which several of the characters project their anxieties and desires.

Feuillade's use of the bodysuit for Musidora can be read as an effort to fix the uncertainty, to stabilise the ongoing fluidity at the level of narrative form and visual style. However, the previous use of the suit by Fantômas, and the circulation of Musidora's image beyond the textual boundaries of Les Vampires, shows us that this is only one of many disguises - once again a phantom screen presence.

What Feuillade has done is to offer us an alternative cinematic mode to Griffiths', one that continues in updated variants throughout French cinema. It is predicated on a principle of uncertainty, on a use of cinema that questions our understanding of the real. It is as fluid and elusive a tradition as a cat burglar, dressed in black on a night-time rooftop. - http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/154

Louis Feuillade was a prolific director of French silent films. Feuillade worked in many genres, including comedy and realistic dramas. But today he is most admired for his spectacular serials. These often pitted master criminals against great detectives. Feuillade's work is of very high quality, and is still gripping and entertaining today.

A detailed discussion of Feuillade's staging technique, can be found in David Bordwell's book, Figures Traced in Light (2005).

Some common subjects in the films of Louis Feuillade:

- Sympathetic looks at social outsiders (heroine: La Tare, dwarf: Le Nain)

- Kidnapping, often in boxes (inventor: Le Trust, Juve and police kidnapped by gang: Fantômas contre Fantômas, hero in Episode 5, switchboard operator in Episode 7, heroine in Episode 10: Les Vampires, Licorice Kid: Judex) related (body hidden in trunk for shipping: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, stolen body, Fandor hides in hamper: Le Mort qui tue)

- Conspiracies (stealing formula: Le Trust, Les Vampires, Judex)

- Loving parents and children (couple: La Hantise, Mazamette: Les Vampires, Judex)

- People waking up (fairy of the spring: Le Printemps, drugged secretary: Le Trust, heroine: Le Nain, child: La Hantise, drugged artist, drugged princess after robbery: Le Mort qui tue, drugged Juve in prison: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- Heroes who live with their mothers (Le Nain, Les Vampires)

- Spying on people (telephone exchange: Le Nain, hiding in radiator: Juve contre Fantômas, undercover police always monitor big parties: Le Mort qui tue, listening through floor in apartment upstairs in Episode 9: Les Vampires, mirror surveillance technology: Judex)

- Crooked financiers who exploit the public (Le Trust, Judex) related (phony banker: Le Mort qui tue, crooked businessman Moche: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- Strange eruptions of bizarre events into daily life (elephant on Paris streets: Bout de Zan vole un éléphant, wine barrels and shooting: Juve contre Fantômas, blood coming from wall: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- Parties that are attacked destructively (orgy: L'orgie romaine, sugar trader's engagement party: Le Mort qui tue, costume ball: Fantômas contre Fantômas, gas attack in Episode 5, poisoned wedding dinner in Episode 9, police raid on crooks' wedding in Episode 10: Les Vampires) related (attack on deadline in Prologue: Judex)

- Social events that develop into strangeness (dinner party: Le Récit du colonel, luncheon: Bout de Zan vole un éléphant)

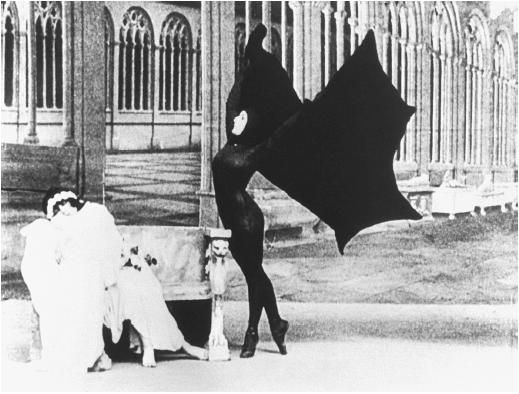

- People and animals intergrading in behavior or appearance (woman fairies with wings: Le Printemps, statute of Sphinx is half-human and half-animal: La Nativité, elephant does human tasks: Bout de Zan vole un éléphant, humans wearing spines to ward off snakes: Juve contre Fantômas, flying in bat costume: Les Vampires, smart dogs: Judex) related (husband tampering with horse and looks similar: Erreur tragique)

- People linked to mythology (water fairy: La Fée des grèves, nymphs: Le Printemps, Water Goddess: Judex)

- Criminals impersonating cops (fake investigator searches pension: Le Mort qui tue, Tom Bob the American detective: Fantômas contre Fantômas, Episode 5: Les Vampires)

- Cops impersonating crooks (Juve and police officers: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- People with multiple identities (Fantômas changes disguise to bellboy in elevator: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, Fantômas changes disguise and identity during car ride: Juve contre Fantômas, Fantômas as banker, Juve undercover: Le Mort qui tue, Fantômas: Fantômas contre Fantômas, Fantômas as justice, Juve as prison visitor, crook as priest: Le Faux magistrate, Grand Vampire, Irma Vep: Les Vampires, hero: Judex) related (heroine's hidden past: La Tare)

- Shots recreating famous paintings of historical events, but with Feuillade's characters (Jacques-Louis David's The Oath of the Horatii, Emanuel Leutze's Washington Crossing the Delaware: Judex)

- Anonymous gifts (play: Le Nain, clothes for prison escape: Le Faux magistrate, ring: Les Vampires)

- Identity theft (using strange gloves: Le Mort qui tue, impersonation in Episode 1, through sound recording in Episode 7: Les Vampires)

- High technology, used by villains (gas: Le Trust, strange gloves: Le Mort qui tue, tampering with gas fire: Le Faux magistrat, gas in Episode 5, sound recording and switchboard in Episode 7, cannon in Episode 8, gas in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- High technology, used by heroes, especially with laboratories or tech locales (ship radio room: Le Trust, telephone exchange: Le Nain, police anthropometry lab, fingerprints used by police, photography at crime scenes, hospital room: Le Mort qui tue, prison light control panel: Le Faux magistrat, lab: Judex)

- Unusual phones (phone on wall near bed: Le Nain, two-receiver phone: Judex)

- Telegrams (Le Trust, La Hantise, fake telegram from Fandor: Juve contre Fantômas, Episodes 1, 9: Les Vampires)

- Flashing, regularly repeating lights (ship radio room: Le Trust, Eiffel tower: La Hantise, code message from lights sent to Fantômas in prison: Le Faux magistrat, letters of fire: Judex)

- Attacks on pseudo-science (expose of palmistry: La Hantise, medium in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Sympathetic technologist characters (inventor: Le Trust, doctor and nurse in hospital: Le Mort qui tue, hero and lab: Judex)

- Going to the movies (Erreur tragique, Les Vampires) related (text projected on screen in theater: Le Nain, reporters include newsreel camera man in Episode 6: Les Vampires)

- Hiding places (document in blotter: Le Mort qui tue, body plastered into wall, loot in floor cavity: Fantômas contre Fantômas, jewels in bell: Le Faux magistrat, cavity behind sliding painting in Episode 1: Les Vampires)

- Streetcars (Paris: Juve contre Fantômas, Louvain: Le Faux magistrat)

- Large bodies of water (Titanic at sea: La Hantise, Fandor pushed into river from sewer outlet: Le Mort qui tue)

- Women and moving water (nymph of the spring: Le Printemps, Musidora and water mill, the Water Goddess: Judex)

- Shadows (Episode One: Judex)

- Silhouettes (man leaving theater: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, after explosion: Juve contre Fantômas, sewer attack: Le Mort qui tue)

- Mirrors (dressing room mirror within mirror: Les Vampires, mirror surveillance technology: Judex)

- Depth staging (entrance of Juve in double door, theater: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, restaurant: Juve contre Fantômas, party, sewer: Le Mort qui tue, party: Fantômas contre Fantômas, ballet theater in Episode 2 Les Vampires)

- Still women and moving trains (Irma Vep under train: Les Vampires, mother saying goodbye: Judex)

- Women dancing (Le Printemps, couples in restaurant: Juve contre Fantômas, couples doing tango and waltz: Le Mort qui tue, couples dancing at ball: Fantômas contre Fantômas, ballet, Irma Vep dancing, dancing at crooks' wedding in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Pans (hotel entrance, across room: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, over to telegraph office: Juve contre Fantômas, in studio over to corpse and back to door, in Rue Lacourbe building as Fandor discovers corpse: Le Mort qui tue, through wall in two hotel rooms, tailing in street in Louvain, street car in Louvain: Le Faux magistrat, Musidora swims in Episode 5: Judex)

- Vertical movements (up ladder in belfry: Le Faux magistrat)

- Moving camera shots down roads (panicked horses: Erreur tragique, two people on horse in Episode 6, car in Episode 9, car leaking oil, bicycle in Episode 10: Les Vampires, dogs and car: Judex)

- Forward movement from fixed shots in moving vehicle (man walks along edge of moving train: Le Faux magistrat, hero and unconscious heroine in boat Episode 5: Judex)

- Double doors, one open, one shut (La Tare, Le Trust, many rooms: La Hantise, hotel room, living room, Gurn's home: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, Juve's office: Juve contre Fantômas, investigating judge's office, newspaper office: Le Mort qui tue, police station: Fantômas contre Fantômas, Marquis' home, judge's office: Le Faux magistrat, opening shot, exterior at magistrate's building: Les Vampires, Judex)

- Rows of doors, along a building, corridor or train (train, walk along moving train edge: Le Faux magistrat, ballet theater exits in Episode 2. apartment in Episode 10: Les Vampires, Vallieres apartment hall, train and station in Episode 3: Judex)

- Hallways with doors (pension: Le Mort qui tue, Moche's building: Fantômas contre Fantômas, Saint-Calais Palais de Justice: Le Faux magistrat)

- Other repeating modular rows of architecture (row of train windows, row of cellar windows: Juve contre Fantômas, sidewalk cafe with repeating tables and decor: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- Strange rapid stunts involving people exiting from high windows or balconies (kidnapping of hero from his apartment, of heroine in Episode 10: Les Vampires, Little Jean's rescue from Cocantin's apartment: Judex)

- Polygonal rooms, with cut-off corners (investigating judge's office: Le Mort qui tue, dressing room in Episode 2, apartment upstairs in Episode 9: Les Vampires, mother's room as teacher, Giselle's: Judex) related shapes (window in hotel room door in Episode 6: Les Vampires, writing pad in Episode 5: Judex)

- People climbing up or down sides of buildings, or on roofs (roof of Palais de Justice: Le Mort qui tue, last stage of workmen climbing down scaffolding: Fantômas contre Fantômas, end of Episode 1, Episode 9, rolling down on rope, garden wall in Episode 10: Les Vampires, Musidora's descent down mill: Judex)

- Diagrammatic, non-realistic architecture (Fandor climbs down chimney: Le Mort qui tue)

- Deserted architecture, often at twilight (Episode 1: Judex)

- Large building facades (construction site: La Tare, chateau: Erreur tragique, steps outside train station, bookstore and shops, telegraph office: Juve contre Fantômas, Palais de Justice steps: Le Mort qui tue, Palais de Justice in Saint-Calais, prison, wall and gate of prison: Le Faux magistrat, Dr. Nox's chateau, magistrate's in Episode 1, wall and chateau in Episode 9, Avenue, crooks' house in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Spiral metal work (bed in ward: La Tare, gates: Erreur tragique, top of fence at Beltham mansion: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, top of grillwork outside sidewalk cafe: Juve contre Fantômas, street doors of Rue Lacourbe hideout: Le Mort qui tue, gates in Episode 1, wall decoration, gates in Episode 10: Les Vampires, door, gates: Judex)

- Helix (chair spokes in artist's studio: Le Mort qui tue)

- People sticking out their arms to make X shapes (Fantômas after explosion: Juve contre Fantômas, Irma Vep dance in Episode 8: Les Vampires)

- Circles (photo of actress: Le Nain, pavement circles around Paris street trees, barrels in shoot-out, vat: Juve contre Fantômas, masked view of roof through binoculars, curb after Palais, wall plaque in artist's studio: Le Mort qui tue, masked view of cellar, barrel hiding Fandor in cellar: Fantômas contre Fantômas, curved tracks of street-cars, round tower at prison gate: Le Faux magistrat, building windows and arches in Episode 1: Les Vampires)

- Triangles (chimneys on Palais de Justice roof, composition with stair in Rue Lacourbe: Le Mort qui tue, wall worker's ladder and sawhorse, ladders in abandoned quarry, chains in quarry pit, stair in quarry cellar: Fantômas contre Fantômas)

- Men with desks (doctor, heroine: La Tare, good businessman, private eye: Le Trust, hero: Le Nain, hero: La Hantise, Juve: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, Juve: Juve contre Fantômas, investigating judge: Le Mort qui tue, crooked businessman Moche, police chief, police interrogator: Fantômas contre Fantômas, judges: Le Faux magistrate, editor, Dr. Nox, hero at home, Satanas: Les Vampires, Judex: Judex)

- Good organizations using common tables (clinic: La Tare, reporters: Le Mort qui tue, reporters: Fantômas contre Fantômas, reporters in Episode 1: Les Vampires) related (dinner party: Le Récit du colonel, wedding dinner in Episode 9: Les Vampires)

- People hide behind curtains (lost finale: La Hantise, princess' room, rendezvous with actor: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, art studio, princess' boudoir: Le Mort qui tue, hero in magistrate's office in Episode 1, medium, Mazamette in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Letters (text projected on screen in theater: Le Nain, letters on card that appear, initials in hat and address book: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, anonymous message of cut-out letters: Le Mort qui tue, animated anagrams, invisible writing appears in Episode 9: Les Vampires, letters of fire: Judex)

- People in related-but-different clothes, often with degrees of formality (white tie and tuxedo at party: La Hantise, Juve and Fandor at restaurant: Juve contre Fantômas, policeman and sugar trader at party: Le Mort qui tue, villain and hero at ballet: Les Vampires, Judex and brother: Judex)

- Men's evening wear (villains in tuxedos with masks: Le Trust, white tie and tuxedo at party: La Hantise, (white tie and tuxedo at restaurant: Juve contre Fantômas, white tie and tuxedo at party: Le Mort qui tue, hero in tuxedo in Episode 1, men at ballet in white tie: Les Vampires, Judex in tuxedos: Judex)

- Men's top hats and canes (guests get them when leaving party at end: Le Récit du colonel, men get top hats and canes after theater performance: Le Nain, Juve's cane: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, Juve and Fandor's top hats in restaurant, Fandor's cane: Juve contre Fantômas, Fandor's cane while escorting woman on street: Le Mort qui tue, hero's cane in Episode 1, villain's top hat in Episode 2, Moreno's cane in Episode 7: Les Vampires, Vallieres' top hat and cane: Judex)

- Men's cloaks (actor: Fantômas - A l'ombre de la guillotine, Fantômas over body suit: Le Mort qui tue, reporter when impersonating Fantômas: Fantômas contre Fantômas, villain with evening clothes in Episode 2: Les Vampires, hero: Judex)

- Body suits or stockings, all-black (Fantômas: Juve contre Fantômas, villains: Le Mort qui tue, Fantômas, impersonators of Fantômas: Fantômas contre Fantômas, black in Episodes 1, 2, dancers in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Body coverings, all-white (doctor, nurse, patient Fandor: Le Mort qui tue, workers' white coats: Fantômas contre Fantômas, white lab coats and masks in Episode 9: Les Vampires, banker in white shroud: Judex)

- Hoods (villains: Le Mort qui tue, kidnapper at window in Episode 10: Les Vampires)

- Women's shawls or wraps that can be spread out or closed up (bat costume, Irma Vep's shawl in dance: Les Vampires)

- Kohl (that dark stuff Musidora wears as eye shadow) - http://mikegrost.com/feuillad.htm

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar