Čovjek je beketovski mehanizam za razmnožavanje, to smo znali. I da je ljubav okrutnija od smrti. Ali kad to spojiš zajedeno...

The Noisy Requiem revolves around Makoto Iwashita, a homeless serial killer who murders young women so that he can harvest their reproductive organs. He collects these visceral mementos so he can stuff them in the belly of his lover, the model woman of his desire, a mannequin. Makoto lives on the roof of an abandoned tenement building with his wooden mistress, making love to her through a makeshift vagina. The organs he acquires are to ensure that she can bear his child, which she eventually does until tragedy falls upon their happy home. The film follows Makoto through his daily routine: feeding some pigeons, decapitating them, finding some other chicks to murder and maim, and landing a job as a sewer scooper for a pair of incestuous midget siblings. We are also introduced to an older vagabond who carries with him a severed tree trunk that looks remarkably like a woman’s torso. The rest of the film’s inhabitants are the actual people who live in Shinsekai, floating in and out of the periphery like ghosts in a forgotten district of hell.

All of this happens within the first ten minutes of the film. Not a single word of dialogue has been spoken, aside from the few monosyllabic grunts here and there. Makoto practically melts into the background, a killer in plain sight, completely ignored by everyone around him. We then cut to a scene at the park, where two young schoolgirls watch some busking war veterans beg for change. One of the girls tells her friend of the dream she had the night before. In it she watches a pure white dove compete for breadcrumbs. As the bird struggles for each scrap of food, it begins to transform into a black crow, as the breadcrumbs become human remains. As the girls give the buskers some money, she explains that it was only natural for the dove to become a crow, for out of desperation to find happiness we all lose our innocence. These are some pretty profound words coming from the mouths of a couple of kids just shooting the shit in the park. But the film’s director, Yoshihiko Matsui, has clearly defined where Makoto is coming from and where he will inevitably go. All the film’s crows are that way out of necessity — still desperately searching for attention and love in a society that has abandoned them.

The Noisy Requiem is very much a product of Japanese cinema in the 1980s. The era marked the beginning of the end of an era that encouraged and supported innovative filmmaking, and the beginning of the next generation of underground filmmaking — one born out of necessity and circumstance.

The great radical masters of the previous decades — Nagisa Ôshima, Shôhei Imamura, Shûji Terayama, Hiroshi Teshigahara, and Kazuo Kuroki — had been assimilated and spat out by the mainstream studios, some of them producing their swan songs before fading away, unnoticed and unappreciated. The Art Theater Guild of Japan, which had fostered independent filmmakers, producing many groundbreaking films throughout the sixties and seventies, was getting out of production altogether. Only a handful of films came out of the ATG before it closed up shop in the mid-80s. But by this point the country’s major studios were already flailing in a bone-dry creative pool. The majors had co-opted the themes and visual styles from underground cinema, sanitized it for mainstream audience consumption and left the masters behind; at the same time, the studios were moving towards a vertically integrated system that would force independent producers like ATG out of business.

Out of the collapse of the ATG came a new movement that favored a more DIY approach to filmmaking. Driven by Japan’s growing underground punk music scene, young filmmakers took the cheapest route available: 8mm (Japan continued using single gauge 8mm film long after Super 8 was introduced in the West). Yoshihiko Matsui emerged from this tradition along with Sogo Ishii, both film students at Nihon University. Sogo Ishii would quickly gain a name for himself with the growing v-cinema boom and cyberpunk movement that took off at the start of the decade. Ishii’s Panic High School and Crazy Thunder Road were all completed while the director was still in film school and are all considered required viewing by hardcore fans of the movement. Matsui Yoshihiko worked closely with Ishii during this time and acted as Assistant Director for most of Ishii’s early films. In turn Ishii shot Matsui’s debut feature Rusty Empty Can and his sophomore effort, the elegantly titled, Pig Chicken Suicide.

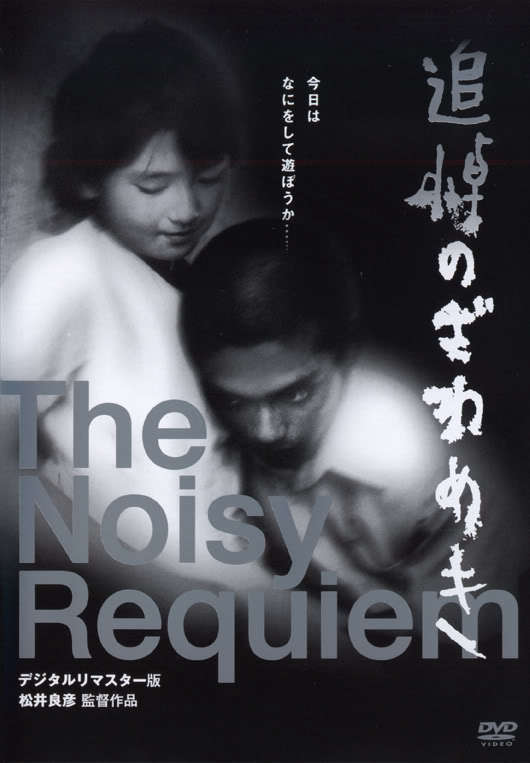

Matsui’s next film was The Noisy Requiem. It wasn’t completed until several years after Pig Chicken Suicide, and it took a while for a distributor to pick it up. It was not merely Matsui’s finest film, but his most distinctive, an evolutionary step beyond his previous films, which owed much to the style of his partner-in-crime Ishii Sogo. Since the cyberpunk movement was gaining popularity, The Noisy Requiem became an immediate underground success, but it evaded critical attention at home and abroad. The reviews that it did get were polarized, and focused mainly on its disturbing plot points and characterizations. Its stark black-and-white, hand-held 16mm photography add to its already unnervingly naturalistic feel; there is a strong sense of immediacy to the film. Yet there is still a feeling of timelessness. At points it feels like a documentary that slips into moments of madness and sublime expressionism. Perhaps the film was ignored because of its setting in a homeless community of Kamagasaki, Shinsekai in Osaka. To this day, the Japanese government has still maintained the absurd claim that there are no homeless people in Japan, an idea that immediately falls apart if you’ve even been to any city in the country; a collective national urge to ignore the guy who scored a refrigerator box for the night could explain why a film like The Noisy Requiem went largely unnoticed.

As Johannes Schönherr (at Midnight Eye) already pointed out, the first ten minutes of The Noisy Requiem firmly establish Matsui’s worldview and, with Shakespearean bravado, foreshadow its unavoidable outcome. From the moment our schoolgirls leave the frame the film takes a derisive turn in many stylistic directions. Makoto soon enters the scene to accost the two buskers. Matsui suddenly walks away from the action before the argument culminates into violence. Matsui’s camera spastically revolves around the park, coming full circle to the action as Makoto starts beating the crap out of the handicapped veterans. Makoto represents the blackest of crows in our already pitch-black aviary. But as Matsui will soon reveal, the depths of his obscene depravity are matched only by his obsessive devotion.

As the film continues we are introduced to our two white doves: a beautiful young couple dressed in white. We never learn their names or how they ended up in Shinsekai, but we immediately recognize that they are innocent, and very much in love. Matsui overexposes the scene so that the characters are surrounded by pure white light, erasing everything else around them. They are never referenced within the film and never speak throughout their transformation, their transformation to hungry black crows, pecking at the rest of the dead. At first it seems as though this couple is meant to contrast Makoto’s black crow, but as the film progresses we witness our white dove’s fall from grace, driven by the boy’s lust for the girl. As hard as they try to maintain their innocence, their environment ultimately corrupts them. By showing the couple unable to resist temptation, Matsui only strengthens Makoto’s purity in his devotion to his mannequin. His love for her is real enough, and there is no distraction from his loyalty to her.

There is no question that Makoto’s love for his mannequin is pure. We see how they first met, the moments they share together, cleaning her, tending to her, protecting her, and killing for her. This is all shown in such a way that we cannot help but empathize with Makoto. In a style usually reserved for romantic melodramas, Makoto dances with her as the camera revolves around them, with pools of filth glimmering around them in the moonlight. Later in this scene Makoto confesses his hatred for the world around him. Like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, Makoto is waiting for the cleansing rain to wash away the dirty streets and disgusting people he sees outside of Shinsekai. Matsui’s seems to share Makoto’s view of morality in Shinsekai and of the outside world.

Matsui defends Makoto as an honorable character, but like everyone in the film, his obsession will only lead to ruin. There is no other outcome for these poor souls, and each will meet their own grisly death. Everyone is desperately clinging to whatever they can in a place that has forsaken them, and Makoto’s rooftop home offers a place for them to indulge in their passion. But saying that the characters lack any moral compass is problematic once Matsui shows how people act in “the outside world.” Matsui portrays normal society as something equally disgusting, and in some scenes he simply hides his camera and records the reactions of “normal society” to his characters. In another scene a busload of senior citizens bust out laughing when a midget woman falls over (twice). Although this scene was clearly staged, it doesn’t paint a pretty picture of a supposed moral society. Matsui doesn’t condone Makoto’s actions, but it is clear that Matsui considers him noble in his dedication to his mannequin.

Most recent reviews of the film are quick to call Matsui’s style nihilist and disturbing, and certainly after reading the above synopsis you would probably agree. Matsui’s guerilla filmmaking approach reinforces that kind of reading, especially since much of the film was clearly shot without permits or permission. Matsui actually set the roof of a building on fire near the film’s climax, and then snuck away to a neighboring building to film the fireman and cops sniff around the remains of Makoto’s makeshift home. Matsui’s complete disregard for linear storytelling offers a glimpse into the reality of Kamagasaki, often leaving characters behind while the camera walks up and down the street showing the real inhabitants going about their lives. Flawlessly edited, the cinematography flows effortlessly from vérité to dream-like fantasy, kinetic and visually abstract. But also slow paced, lingering on beautifully composed moments of horror and misery, as well as love and desire. Some viewers might avoid the film because of the described violence, or others may have high expectations to see some crazy J-style weirdness. The Noisy Requiem stands apart from most genre classifications, and certainly should not be lumped together with other v-cinema cyberpunk films of that period. The violence is disturbing, but it is never graphic or fetishized. It is a deeply personal film, made with compassion for it’s subject matter and an understanding of what innovative cinema can be. Like many of his mentors from the ATG, Matsui was able to evoke the spirit of his generation while maintaining his own unique vision. Having a film like The Noisy Requiem in the Criterion Collection would give Matsui the recognition he deserves, and would allow the Western world to see one of the most important independent films to come out of Japan since the fall of the Art Theatre Guild.

Osaka still has some exquisitely dirty corners that have successfully resisted all urban clean-up campaigns. Of course, to Tokyo-ites the whole city may seem untidy and virtually all its inhabitants may come off as particularly rude folk. Well, Osaka is an old hustle-and-bustle merchant city and the customs are a bit different there from the capital, with all its masses of government bureaucrats. But there are some areas where even tough-mouthed Osakans rarely venture. Take Shin Sekai, for example. It translates as "New World", and that's exactly what it once was supposed to represent. Various grand-scale EXPO-like events were staged there in the late years of emperor Meiji (that means in the 1910s) and the Tsutenkaku Tower, a sort of smaller version of the Eiffel Tower, is still the major landmark of the area, dating back to those times when a young and hungry Japan was challenging the world.

To build all those grand monuments of a rapidly modernizing Japan, large numbers of day laborers were drafted in, and most of them ended up staying on... slowly turning the "New World" into their world. Today, the Kamagasaki neighborhood of Shin Sekai is Japan's biggest homeless area and the closest thing Japan has to an actual slum area. The rest of Shin Sekai either turned to the red-light business or remained trapped and frozen in time. Walking through the shopping arcades there today with their cheap and trashy thrift stores and plethora of drinking outlets is like stepping back in time... like entering the movies and going straight back to 1962 at one corner or to 1973 at another. Never back to a happy past, though, but back to a desperate post-war Japan mired in poverty.

This area is the setting and location of Yoshihiko Matsui's radically nihilist Noisy Requiem. This black and white movie opens with a freeze frame of the main character Makoto (Kazuhiro Sano) walking straight through the homeless ghetto of Kamagasaki. The freeze-frame springs to life, and he walks absent-mindedly towards the camera. Cut to him feeding pigeons in the park, then taking out a claw-hammer and killing a bunch of them. Whistling, he lays down on a park bench and rips the heads off the dead birds. Shots of ghastly homeless shuffling through Kamagasaki, shots of Makoto killing women in dirty backlots next to busy railway lines, cutting organs out of their bellies and stuffing them in a garbage bag. Makoto and a mannequin doll on the rooftop of the abandoned warehouse where he lives. He cuts the mannequin a vagina and stuffs the bloody entrails of the murdered women in there.

We are still right at the beginning of the movie at this point, and not a line of dialog has been spoken. The first spoken lines come from two uniformed schoolgirls who wander through the park where Makoto has killed the pigeons.

While they sit down near two blind war veteran buskers, one of them tells her previous night's dream to the other. There was a boy feeding pigeons, she says, and there was one white pigeon that couldn't get any of the grain because the many other grey pigeons constantly got in its way. So, the white pigeon turned black ... it became a crow. Suddenly the scenery changed, she explains, crows fed on thousands of dead people. The white pigeon that had turned into a crow joins in. The girl walks over to the buskers and gives them some money, then continuing: "Everybody turns into a crow when they're hungry."

Now, this is the key line of the movie. All characters in the film are desperately hungry for something humane: mainly for love but for some characters a little bit of tender attention or at least some basic form of acceptance will do. Being constantly denied any of this, they all turn into vicious crows. Or rather, extremely troubled humans. Shortly after the girls leave, Makoto enters the scene. He insults the busking war veterans and questions the war credits they claim, accusing them of being "lazy Koreans" who "did nothing during the war". He gets his claw hammer out and ... well, I'm not going to describe the scene. You've got to watch it. Interesting thing is, though, that Makoto comes off at that moment as an extreme Korean-hating fanatic. In fact, later moments in the movie suggest that he is more likely to be a closet Korean himself.

The plot continues with Makoto getting a job as an underground sewage line cleaner, working for an incestuous brother-sister midget couple. He is wildly in love with the mannequin he has stuffed with the organs of the women he had killed - in order to give it the means to bear his child. A crazy, sex-starved bum who takes advantage of the same mannequin when Makoto is not around will meet a gruesome fate in a particularly memorable scene.

In short, virtually everybody who shows up in the movie has already reached the end of the line in some respect at the point at which they are introduced... they had already been transformed from the virgin white pigeons to the black crow. But from the moment they appear, things get invariably worse for all of them. Death is the only way out and death doesn't come easily in this film.

Add to that the rough guerilla street-level b&w photography done right in the midst of the Kamagasaki homeless area and a cast that includes a host of truly bizarre characters played by unknown but terribly convincing actors and you got a movie that looks like its emerged straight out of hell. And with guerilla filmmaking I mean guerilla filmmaking: I don't know about any other Japanese filmmaker who would have a character of his film setting the entire rooftop of an abandoned building right in the middle of the city on fire, obviously without any permission, film it from a neighbouring rooftop, then sneak back and shoot the unsuspecting firefighters as they are dealing with the inferno.

When writer-director Yoshihiko Matsui finished his script, nobody thought there would be any way of transferring those typed pages into actual images on celluloid. By that time, in 1983, Matsui had already been a member of Shuji Terayama's radical avant-garde theater group for a few years. Terayama, himself no stranger to controversy over his works (especially his ground-breaking film Emperor Tomato Ketchup from 1971) and generally being considered one of most provocative Japanese artists of the time, commented: "It would be a scandal if this script were actually to be made into a motion picture."

Matsui, however, had an extensive background in no-holds-barred filmmaking and he had heard the word "impossible" too many times before to be bothered by such comments. He had been a founding member of Kyo-eisha, the filmmakers' group led by Sogo Ishii when he started out as a film student making punk rock biker movies in the 1970s. Matsui worked as assistant director on quite a number of those early Ishii adrenaline overflow adventures, like on his 1976 Panic High School and his roller-coaster biker battle pic Crazy Thunder Road (1980). Ishii himself was the director of photography on Matsui's first own production Rusty Empty Can (1979). Matsui's second film, Pig-Chicken-Suicide (1981) was a painful examination of a failed love story between a Zainichi boy and girl. Though graphic in the details (lots of animal butchery) and featuring a final scene of the girl masturbating in her room to Emperor Hirohito's speech announcing Japan's surrender in the Pacific War while the boy is spying on her before being blown off her veranda by a rainstorm, Pig-Chicken-Suicide was a rather experimental film, requiring a very sober and focused mind to make sense out of what actually happened on screen. Very different from Ishii's high-speed works but somewhat closer to Terayama's often mysterious experiments.

With Noisy Requiem, Matsui finally found his own unique voice: slow-paced, intense, cruel, and telling a tale of epic proportions. It took him 5 years to realize the movie but when it finally premiered in 1988, it became an instant success on the Japanese underground scene. Punk rockers and other outsiders especially could easily identify with the characters prompted into vicious acts after repeated rejection, and their numbers were big enough to turn the film into a (modest) financial success. The movie still shows up occasionally on the Japanese underground cinema circuit and it still has plenty of hard-core fans.

It didn't make it on the international level, however. Matsui had a couple of bad run-ins with international film festival programmers and subsequently refused to have the film shown outside of Japan. The only exception he granted was to a very limited run as part of a "Japanese Cult Film" series originating in Copenhagen in early 1998 and subsequently shown in various cities in Germany and at the Oslo Film Huset.

Despite the success of Requiem, Matsui has not been able to pull off any major work since the completion of that film. But he is back at work right now, preparing his own cinematic interpretation of Natsume Soseki's classic novel I Am a Cat. Lacking major backers, this film will presumably also be shot on a shoestring budget. To finance the new project, Matsui has to get innovative about financial resources... and that may turn out to be a good thing. - Johannes Schönherr

http://www.midnighteye.com/reviews/noisy-requiem/

Somewhere around the late 90's the image of Japanese film began to change. For years before that the term "Japanese film" would bring to mind the top-knotted samurai of Kurosawa and the serene, sad interiors of Ozu. The farthest into darker and more existential territory most mainstream European and North American audiences would venture might be the critically-lauded films of Hiroshi Teshigahara, typified by his 1964 film "Woman in the Dunes". Then come the 90's a whole new batch of films and film-makers began to emerge from Japan's independent and V-cinema scene that would drastically change the perception of Japanese film and the people who seek it out. People like Shinya Tsukamoto and Takashi Miike, and to a lesser extent Shozin Fukui, Kazuyoshi Kumakiri and Hisayasu Sato, began gifting us with shocking, abrasive and irreverent visions where bodies morphed, blood flowed and nary a ray of brightness would reach. In a few years North American and UK distributors were releasing films like Tsukamoto's "Tetsuo the Iron Man", Miike's "Audition", Fukui's "Rubber's Lover", Kumakiri's "Kichiku: Banquet of the Beasts" and Sato's "Splatter: Naked Blood" in stores. These films formed the dark side of the J-Horror boom, something dubbed "extreme cinema", and for young cult movie fans these pitch black visions eclipsed much of what came before from film-makers in Japan. What many didn't know is that there was a director who was working a decade before who had not only released a film that would anticipate this dramatic shift, but also drew direct inspiration from earlier classic cinema. That director was Yoshihiko Matsui and his film was "The Noisy Requiem".

At its narrative core the gritty black-and-white "The Noisy Requiem" is a serial killer film, although one that follows none of the previous or subsequent genre trappings. In the heart of Osaka's run down Shinsekai, or New World" district a killer is hiding in plain sight amongst the bums and the beggars. We first meet Makoto Iwashita (Kazuhiro Sano) as he is strangling and wrenching the head of a pigeon. It's only seconds later that we see that his cruelty is in no way limited to animals. What follows is a montage sequence in which we see Iwashita at work, killing women in back alleys by bashing them over the head with a small crowbar and then carving out their reproductive organs. What he does with these is shove them into a cavity he has hollowed out between the legs of a wooden mannequin which he has lovingly laid out on a bed on his rooftop hideaway. Stomach-churning indeed, but somehow Matsui, who also wrote the screenplay for "The Noisy Requiem", begins to make us somehow empathize with this most anti of anti-heroes. One way he does this is to introduce us to a series of other Shinsekai natives equally as repulsive as Iwashita.

There are a pair of street musician/ beggars, both injured and shell-shocked WW2 veterans who howl and contort on a street corner. Iwashita isn't even convinced these two are Japanese and he brutally beats them, but still they return to their street corner. There is a homeless man portrayed by butoh dancer Isamu Ohsuga who is caked with dirt and feces and drags around a log with an instant resemblance to a woman's buttocks and groin. There are the midget siblings, bother and sister, whom Iwashita gets a job from. The sister was burnt as a child and bares horrible scars on her torso. When she isn't spending time masturbating with an electric dildo she is having relations with her own brother, something that was apparently dictated in their mother's will so that her daughter would know what being with a man was like. Iwashita lays beside his terrifying bride each night pondering the people, horrible like "jellyfish" who are "shoved into his eyes" each day. Navigating amongst this knot of grotesque creatures are a silent couple -- a young man and a little girl. Their presence is a calming one often accompanied by melancholic piano music. If looking for an easy interpretation then these other homicidal, homeless and incestuous denizens of Osaka's underworld might be demons while the young man and the girl are possible angels in the scenario. Even they dramatically fall from grace in the final third of the film though, giving us some of the most shocking images and ideas in "The Noisy Requiem".

There are a pair of street musician/ beggars, both injured and shell-shocked WW2 veterans who howl and contort on a street corner. Iwashita isn't even convinced these two are Japanese and he brutally beats them, but still they return to their street corner. There is a homeless man portrayed by butoh dancer Isamu Ohsuga who is caked with dirt and feces and drags around a log with an instant resemblance to a woman's buttocks and groin. There are the midget siblings, bother and sister, whom Iwashita gets a job from. The sister was burnt as a child and bares horrible scars on her torso. When she isn't spending time masturbating with an electric dildo she is having relations with her own brother, something that was apparently dictated in their mother's will so that her daughter would know what being with a man was like. Iwashita lays beside his terrifying bride each night pondering the people, horrible like "jellyfish" who are "shoved into his eyes" each day. Navigating amongst this knot of grotesque creatures are a silent couple -- a young man and a little girl. Their presence is a calming one often accompanied by melancholic piano music. If looking for an easy interpretation then these other homicidal, homeless and incestuous denizens of Osaka's underworld might be demons while the young man and the girl are possible angels in the scenario. Even they dramatically fall from grace in the final third of the film though, giving us some of the most shocking images and ideas in "The Noisy Requiem".As we first watch "The Noisy Requiem" we wonder two thing. First, we wonder if the debased characters that inhabit the film aren't just everyday folk as seen through Iwashita's lens of hatred and violence. This would give us as an audience an easy way to interpret Matsui's film, or maybe escape or distance ourselves from some of its more nauseating imagery. We soon learn, though, that Iwashita is just one of many damaged and deranged individuals that crawl through the muck of Shinsekai. It's a realization that both gives "The Noisy Requiem" its power, as well as making it a film that many have had problems sitting through. If Iwashita is just another human whose darkest fantasies have erupted into his conscious life then what does that say about us as audience members and fellow human beings?

That brings us to the second thing we wonder, why? Why the violence, why the depravity heaped up by Matsui and "shoved into our eyes" in the same way Iwashita is assaulted by his own world? That brings us to Matsui's important place in Japanese film history. One of Matsui's self-confessed creative heroes was avant-garde poet, playwright and film-maker Shuji Terayama. This is the same Terayama whose remarkable films have yet to catch on in North America due to his debut feature, also a gritty black-and-white film called "Emperor Tomato Ketchup". It, like "The Noisy Requiem", is set in a decaying and surreal world, but it also features simulated sexual encounters involving minors. This has made Terayama, a major intellectual figure in Japan, verboten in the U.S. and Canada. Matsui doesn't take his power to shock though just from Terayama. One only needs to look at the 1960's films of New Wave pioneer Shohei Imamura to see the tradition from which Matsui has come. From 1961's "Pigs and Battleships" straight through to 1968's "Profound Desire of the Gods" the world of Imamura was one steeped in murder, obsession, lust, pornography, incest and black humour. As Imamura was often quoted as saying, "I am interested in the relationship of the lower part of the human body and the lower part of the social structure." Yes, the characters in "The Noisy Requiem" are extreme, but they would not look out of place in the Imamura universe. Instead of being connected to the waist down "lower part of the human body" though Matsui's characters inhabit the creases in our flesh, between our legs, under our armpits, in places we never see, can't reach, the places that breed disease, but are still necessary to our being. Maybe it's this that today's "extreme" film-makers draw from when looking at a film like "The Noisy Requiem".

The work of Yoshihiko Matsui is a wonderful, if often uncomfortable, bridge between the likes of Imamura and Terayama and contemporary violent and confrontational films that pack theatres at genre film festivals worldwide. Impossible to find legally in North America and very expensive to purchase in Japan, "The Noisy Requiem" is a revolting masterpiece, revolting in the true dual meaning of being both at times disgusting, but always revolutionary. A difficult dose of film, but one that is well worth the effort. - Chris MaGee

http://jfilmpowwow.blogspot.com/2011/07/review-noisy-requiem.html

Yoshihiko Matsui's Noisy Requiem is a guttural howl of a film, a quietly despairing, skuzzed-out travelogue through the post-industrial hell of Osaka's slums. It is a film so raw, transgressive, and aesthetically assaultive that its maker has since served out a life sentence in director's jail with little-to-no chance for parole. But behind the art-shock provocations lurks a great tenderness and compassion for its cast of marginalized outcasts and the surrealist wasteland they inhabit. Even as Matsui's art-damaged guerilla aesthetics—the blown-out black and white imagery, droning soundscapes, and frenzied handheld camerawork—threaten to discomfort and go for the big dyspeptic gut-punch, the film itself flirts with something between empathy and full-bore repulsion. It jolts us with violence and heaped-on grotesqueries, buries us in a sea of puke, blood, trash, and shit, and yet it still seethes with quiet longing and a very real sense of sadness. All those misguided expressions of love kinda sting. Review by Chuck Williamson

Absolutely massive in a way few films are, capturing so much of the misery, hatred, and cruelty lurking under the surface of polite society without any of the pretensions that mission usually comes with. Just raw, beautiful ero-guro grime. I think Matsui has become a favorite director in just two films.Review by Perry, the Thing Forsaken by God

Amazing visuals and full of a lot of great absurdist and deadpan comedy, but apart from that it's just an overly long and poorly paced film.

The direction is okay, the effects are hot garbage, and the score made me want to cut off my ears and swallow them whole.

Disappointing overall, really wish it did more with the comedy and punk as fuck style of filmmaking it was going for. I'm not completely turned off by Matsui, but I'm definitely not sold on him either.

Impossible to describe. A horror-meditation on humiliation, pain, and suffering among the dregs of the slums of Osaka. Director Yoshihiko Matsui captures some of the most grotesque and haunting images I've ever seen on 16mm film that must have come from the same depths of hell that captured Tobe Hooper's masterpiece THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE (1974). And much like Hooper, Matsui captures the nihilism that has befallen an unwilling group of individuals that are not exactly punished...but more so guided to the end of their rope. Review by Michael

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar