Rani filmski impresionizam, s mnoštvom tada dostupnih specijalnih efekata. "U vrtlogu suvremenog života najteže je živjeti sam."

Cijeli film:

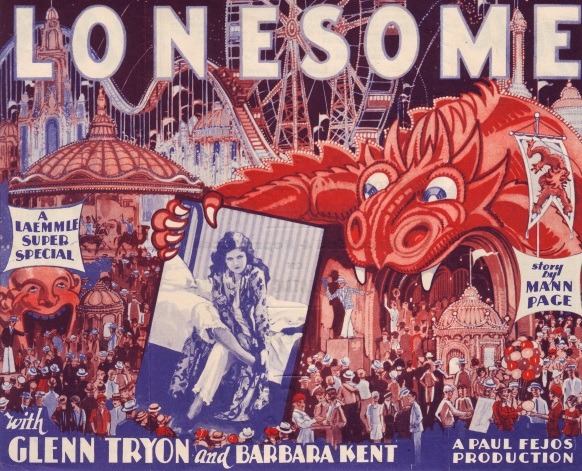

A buried treasure from Hollywood’s golden age, Lonesome is the creation of a little-known but audacious and one-of-a-kind filmmaker, Paul Fejos (also an explorer, anthropologist, and doctor!). While under contract at Universal, Fejos pulled out all the stops for this lovely, largely silent New York City symphony set in antic Coney Island during the Fourth of July weekend, employing color tinting, superimposition effects, experimental editing, and a roving camera (plus three dialogue scenes, added to satisfy the new craze for talkies). For years, Lonesome has been a rare treat for festival and cinematheque audiences, but it’s only now coming to home video. Rarer still are the two other Fejos films from his Universal years included in this release: The Last Performance and a reconstruction of the previously incomplete sound version of Broadway, in its time the most expensive film ever produced by the studio. - www.criterion.com/

PAUL FEJOS began his professional life as a doctor and finished it as the president of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. In between he found time to make a couple dozen feature films in Hungary, Hollywood, France and Denmark, and another dozen ethnographic documentaries made in locales as far-flung as Madagascar and Peru.

At least two of those movies deserve to be called great: “Marie, Légend Hongroise,” a 1933 French-Hungarian coproduction that remains unavailable on DVD, and “Lonesome,” a 1928 part-talkie made for Universal that the Criterion Collection has now released, in a version restored by George Eastman House, on a magnificent Blu-ray; it also includes two of Fejos’s other American films, both released in 1929: “The Last Performance” and “Broadway.”

On the evidence of his biography Fejos was restless; an acquaintance claimed that he changed cities every time a love affair came to an unhappy end. And his insatiable curiosity, his search for new techniques and new ideas, is clear within his films.

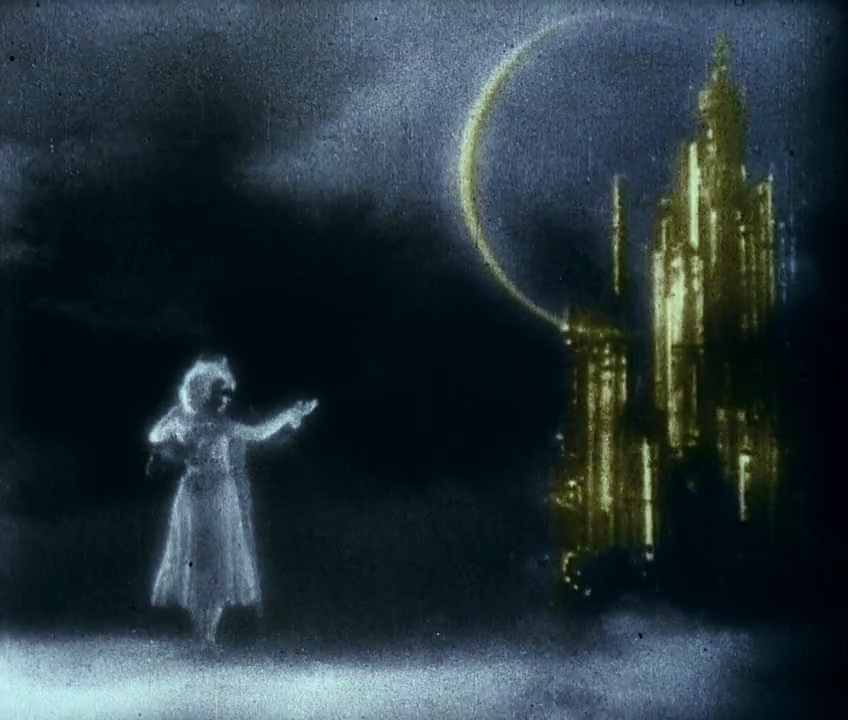

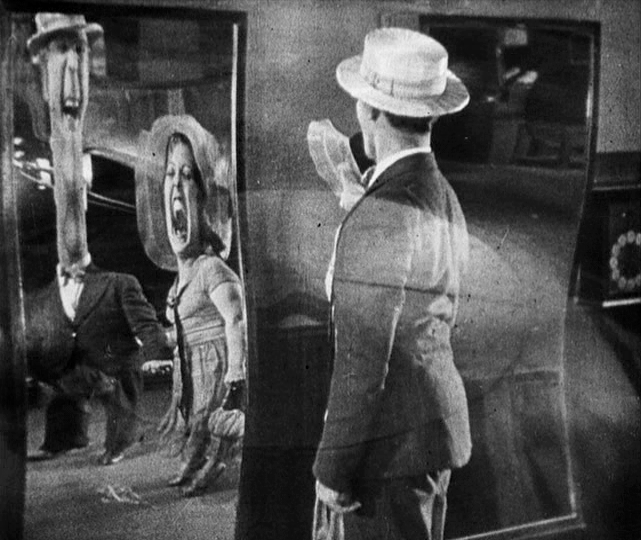

“Lonesome” came along at a time of great creative ferment in the film world, when the Germans, led by F. W Murnau, were developing the possibilities of long takes and elaborate camera movements (Mordaunt Hall, the film critic for The New York Times, reviewed “Lonesome” in the same Oct. 7, 1928, column in which he covered Murnau’s now lost American film “Four Devils”); the Soviets were extending the possibilities of cutting to new expressive heights in films like Sergei Eisenstein’s “October”; and the French, led by Abel Gance and Jean Epstein, were exploring the superimposition of images, among other techniques, to create a loosely defined school of cinematic Impressionism.

“Lonesome” incorporates all of these techniques — Fejos was clearly a voracious and discerning filmgoer — at the same time it embraces the latest technology. Although completed as a silent and briefly released as one, “Lonesome” was recalled and refitted with three dialogue sequences, in addition to an unusually dense synchronized music and sound effects track.

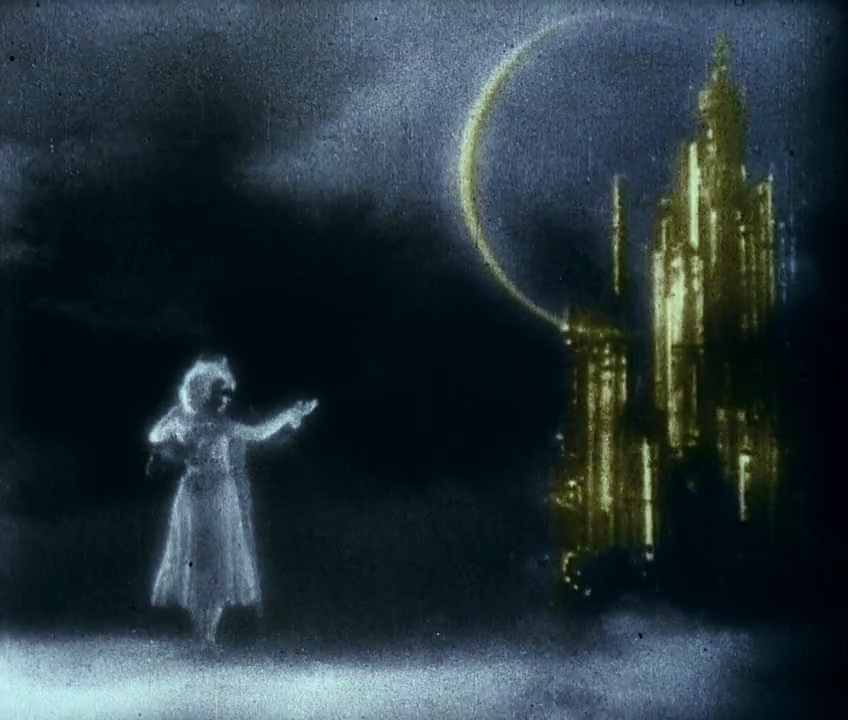

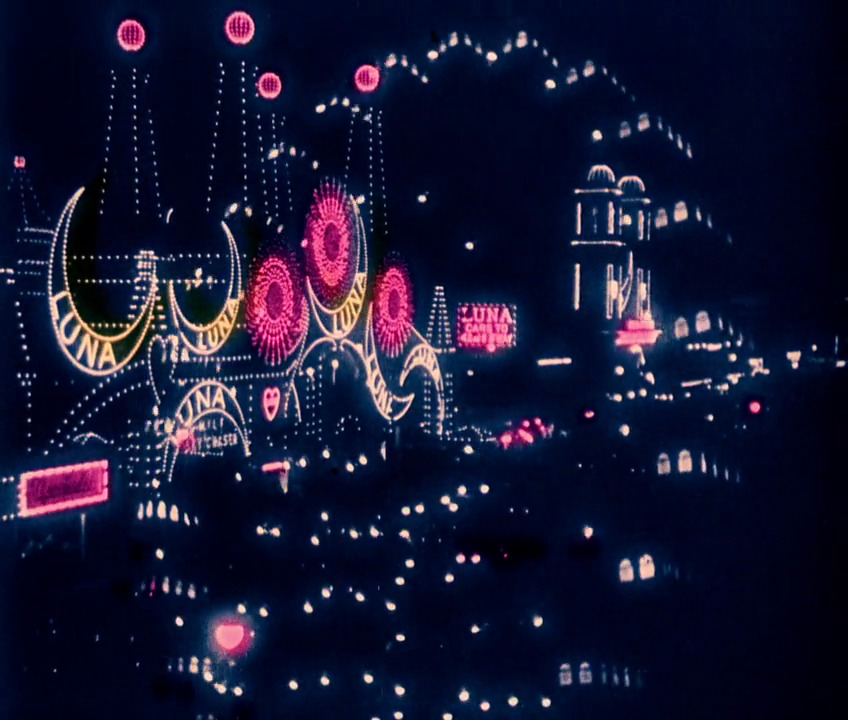

Reviving a technique from the nickelodeon days, Fejos uses hand-stenciled color to add a magical atmosphere to a nighttime Coney Island sequence. And by getting out of the studio and placing his actors among real Coney Island crowds, Fejos is anticipating the principles of neorealism that would be developed in the next few years by directors like Raffaello Matarazzo in Italy (“Treno Popolare,” 1933) and Jean Renoir in France (“Toni,” 1935).

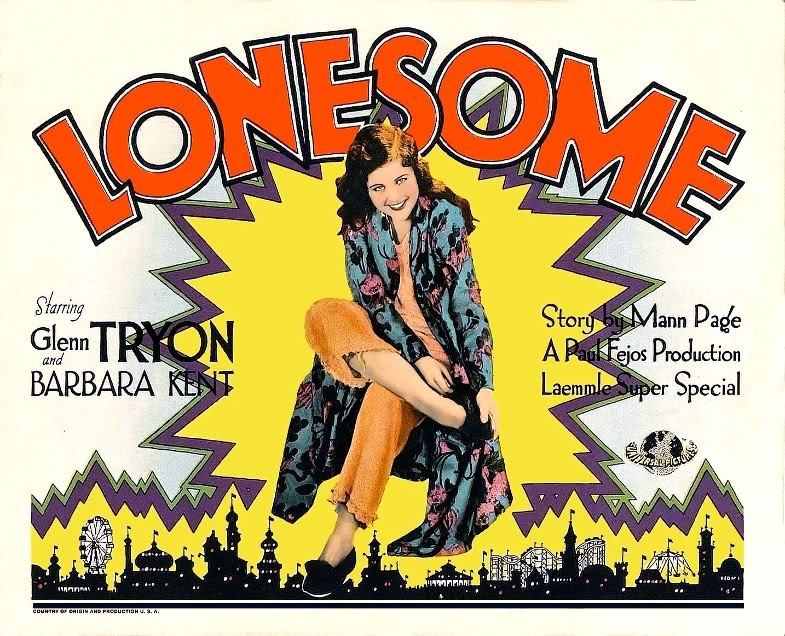

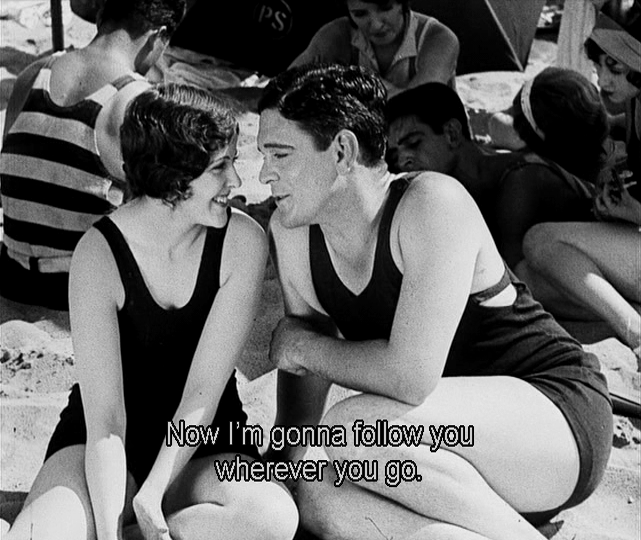

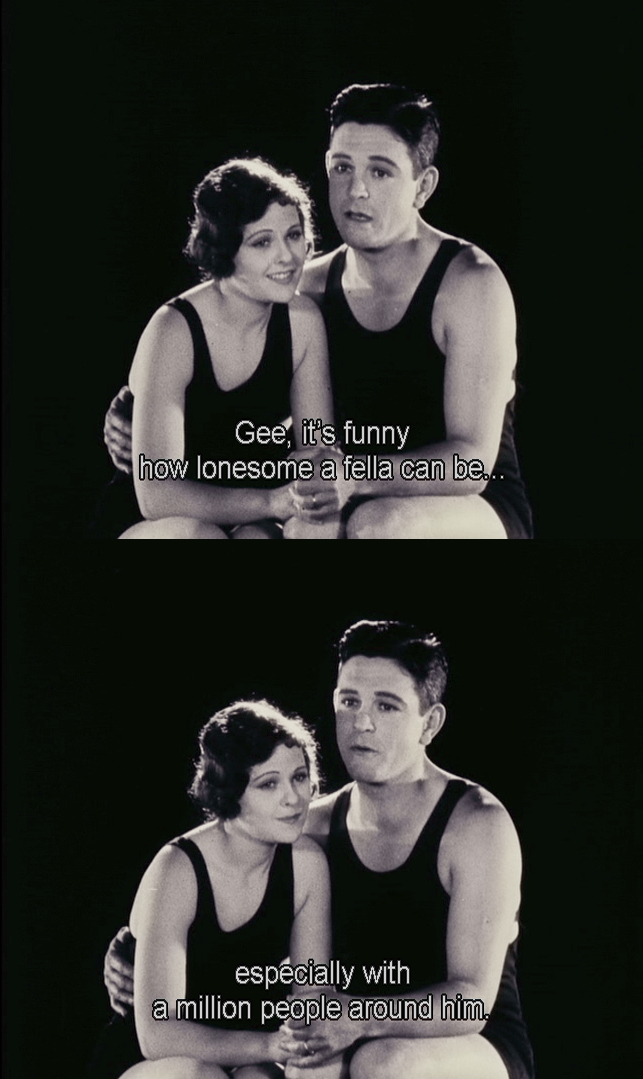

The story has the simplicity of an O. Henry tale. Mary (Barbara Kent), a telephone operator, and Jim (Glenn Tryon), who works a punch press at a factory, find themselves alone and uneasy after their half-day shift on Saturday; impulsively, they take the same bus to Coney Island, where they meet among the teeming throngs at the beach and begin a flirtation.

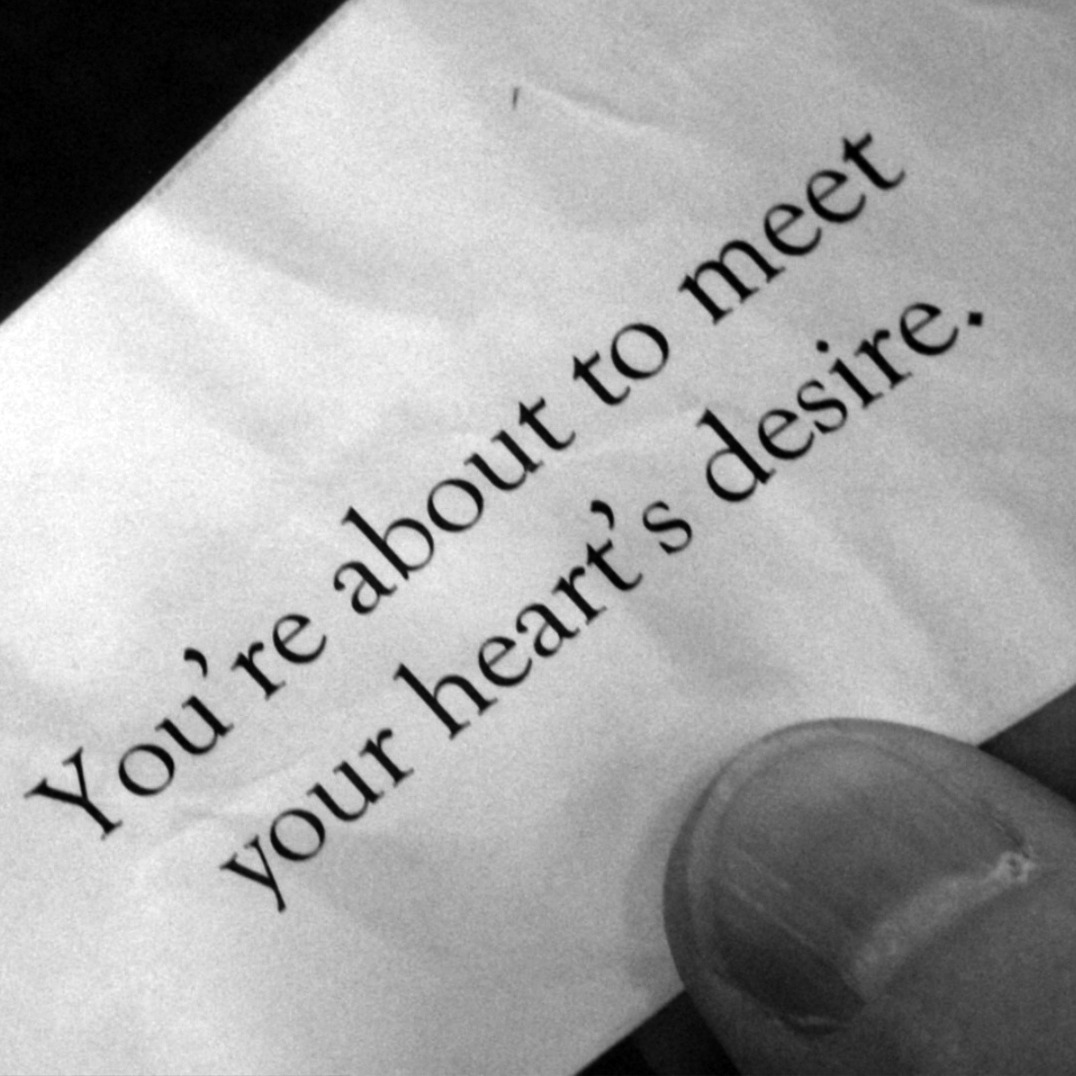

Day drifts into night, and as they talk and play and explore the attractions of the boardwalk together, the bond between them grows. But in the confusion after a near-accident on a roller coaster, they lose each other in the crowd. Dejected, Jim returns to his cramped little room at his boardinghouse, where a surprise awaits that at this point is not a surprise, but which is staged by Fejos with a marvelous matter-of-factness that removes any trace of sentimentality.

“Lonesome” is one of those rare films that combines technical mastery with a deep feeling for human behavior. As much as you may admire the virtuosity with which Fejos sends his camera darting and thrusting around Jim’s apartment — a kinetic, visceral way of evoking his boredom and agitation — the details Fejos settles on are telling.

Jim picks up the build-it-yourself radio kit he’s been working on (something no self-respecting young man of the late 1920s would be without), but this is not a day for projects and pleasures deferred: he’s drawn to his window by the sound of live music, coming from a band, promoting cheap bus rides to Coney Island, performing in the street below. Mary hears the same band, and tosses aside the magazine she’s been leafing through. Their lives are already connected through music (a theme that will return at the climax), though they are still unaware of each other’s existence.

The simple narrative trajectory of “Lonesome” — which covers less than 24 hours in a running time of less than 70 minutes — lets Fejos move through an astonishing range of moods and styles, just where the more complex story lines of “The Last Performance” and “Broadway” seem to hem him in. Criterion has included these two very rare films — the first only recently rediscovered, in a Hungarian print, and the second reassembled from scattered fragments of the sound and silent versions into the first convincing approximation of the original feature — as special features subsidiary to “Lonesome.” That’s fair enough (these are secondary works), but both have their fascinations.

With the German star Conrad Veidt (“The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”) as a stage magician driven to murder by his unrequited love for his beautiful assistant (Mary Philbin, who found herself in a similar position — and among some of the same sets — in “The Phantom of the Opera”), “The Last Performance” gives Fejos the chance to try out the Expressionistic lighting and swooping camera movements of the Weimar cinema. A shot in which Veidt’s giant shadow looms over Philbin and her lover (Fred MacKaye) looks like an outtake from Murnau’s “Nosferatu,” but the drama is flat and its resolution anticlimactic.

In “Broadway,” based on a New York stage hit by George Abbott and Phillip Dunning, Fejos seems barely engaged with the trite, backstage story of gangsters and chorus girls, devoting his attention instead to the film’s true star: the gigantic, 50-foot camera crane that Fejos and his cinematographer, Hal Mohr, had built to cover the cavernous nightclub set that is the film’s central location.

With the help of an enormous counterweight, the camera sails through space with a speed and agility that suggests the most advanced digital effects of today, rocketing (at a reported “600 feet a minute”) from eye level to a point of view three or four stories above the action. You can hardly blame Fejos for becoming distracted by such a marvelous toy. Nicknamed “the Broadway Crane,” the amazing apparatus remained in use at Universal for decades, though it never again found such a daring and inspired pilot. - Dave Kehr

Paul Fejos' Lonesome comes from that awkward time in film history when silent cinema was transitioning into sound. Of course, everyone wanted the newest technology, and the appeal of talking movies could not be stopped. And, as Andrew Sarris pointed out, "a tender love story in its silent passages, Lonesome becomes crude, clumsy, and tediously tongue-tied in its 'talkie' passages added to the finished film to make it that hybrid monstrosity of the period, a part-talkie."

But Jonathan Rosenbaum hailed it as an "exquisite, poetic masterpiece" and that the film "deserves to be ranked with F.W. Murnau's Sunrise and King Vidor's The Crowd from the same period."

They're both right. Lonesome only contains three "talkie" passages, none of which last more than a minute or two. They were clearly added on later, as shown by the displacement of time. In the second one, our two lovers Mary (Barbara Kent) and Jim (Glenn Tryon) sit and talk at the beach until it gets dark. The movie dissolves to a "talking" sequence with some hackneyed dialogue, which then ends with the lovers noticing that it has grown dark. Dissolving back to the silent footage, the lovers once again look around and notice the darkness.

In the third sequence, Mary and Jim become separated after an incident on a roller coaster. Jim tries to push his way through the crowd to get to Mary, but is waylaid by a cop. Cut to a "talkie" sequence in which Jim has been arrested and speaks to a judge (some prison bars are in the foreground, suggesting that he's in trouble). Suddenly the judge decides to let Jim go and he returns to the carnival, seemingly just seconds after he left it.

Not only are these talkie sequences awkward, but also they're totally unnecessary and clearly not a part of the original plan. Nowadays the film might have the opposite of its intended effect. In 1928, audiences would have paid to see the talking sequences, but today's audiences -- in the age of the successful San Francisco Silent Film Festival as well as The Artist -- would no doubt laugh at the talkie sequences and appreciate the silent sections.

The silent stuff is lovely and does indeed recall Sunrise and even Man with the Movie Camera (which came later) in its depiction of a mechanized city. The very simple plot has Jim as a machine operator in a factory, and Mary as a phone operator. We see them waking and commuting to work, cross-cut as Jim rushes and Mary takes her time. After work, it's the Fourth of July holiday and all the couples meet up and head out for some excitement. Separately, Mary and Jim go home, but when a marching band appears beneath their respective windows, they decide to go to Coney Island. They meet on the beach and spend the day together, falling in love. Then they are separated, and desperately try to find one another again.

Director Paul Fejos, who came from Hungary, had a brief career in Hollywood and eventually quit filmmaking to become an anthropologist, clearly enjoyed finding the rhythms of the city, and depicting them in a visual way, such as a man eating something that looks like fish on the subway, and Jim trying to determine where the smell is coming from. The movie uses lovely mirror-like balance to show the opposite, yet similar lives of Mary and Jim, and their little routines. At home and bored, they both pick up the same magazine. Giving up, Jim throws his over his shoulder while Mary gently places hers on the table.

In the end, I'd call Lonesome a truncated masterpiece, with footage rudely added rather than stripped away. It seems easy enough to simply take out the three sound sequences and let the beauty remain, but it's also important to leave them in for historical purposes, and certainly Fejos himself never seemed interested in a "director's cut." So, appreciate Lonesome for its timeless love story, and at the same time for its very specific 1928 issues of marketing and commerce.

(Aside from the talkie sequences, the credits are also amusing: they include Fay Holderness as "Overdressed Woman," Gustav Partos as "Romantic Gentleman," and Eddie Phillips as "The Sport." I was unable to identify these three characters over the course of the film. Can anyone else?)

The Criterion Collection has resurrected this little-known film for a new DVD and Blu-ray. If it's not as impressive as other Blu-ray presentations of films from the same period (such as Criterion's People on Sunday), it's probably because of the rarity of the source material. But it's as good as we're likely to get. Extras include an enthusiastic audio commentary by film historian Richard Koszarski, a 1963 visual essay on Fejos, and a liner notes booklet with essays by Phillip Lopate and Graham Petrie, and an interview with Fejos.

The biggest bonuses are two other, full-length Fejos features, produced at Universal at around the same time. The Last Performance (1929) is a silent feature, starring Conrad Veidt and running about an hour. And Broadway (1929) is a sound feature, running an hour and 45 minutes. Neither of these has been restored with the luster that Lonesome has, so they will be reserved for die-hards. - Jeffrey M. Anderson

This is probably a stretch of comparison, but something like the Hausu (1977) of the late silent/cusp-of-the-talkie era (the film includes three dialogue scenes), Fejos’ unexpectedly eccentric and robustly energetic film is a wildly stimulating and inventive film — using, like Nobuhiko Obayashi’s aforementioned cult film, all manners of editing, juxtaposition, collage, color tinting and basic filmmaking available at the period. Romantic, tragic and touching upon working class ambitions in a pointedly gender-divided world, Lonesome is a true, memorable find and an absolute joy to watch, recently restored and given the proper DVD/Blu-ray treatment by Criterion. - www.tumblr.com/tagged/paul-fejos

http://fan.tcm.com/_LONESOME-by-Paul-Fejos-1928/video/1607174/66470.html

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar