Ludi slikari uvijek su dobrodošli na ovom blogu. Dadd je gotičar 19. stoljeća, zaklao je oca u parku pa su ga strpali u ludnicu, gdje je naslikao svoja fantazmagorijska remekdjela. Njegov svijet kipi čudnim sitnim bićima.

The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke

Richard Dadd’s Master-Stroke

Nicholas Tromans, author of Richard Dadd: The Artist and the Asylum, takes a look at Dadd’s most famous painting The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke.

ichard Dadd was a young British painter of huge promise who fell into mental illness while touring the Mediterranean in the early 1840s. He spent over forty years in lunatic asylums, dying at Broadmoor in 1886, but never gave up his calling, producing mesmerisingly detailed watercolours and oil paintings of which The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke is now the most well known. The picture’s history encapsulates the peculiar rise and, if not fall then the suspension, of its maker’s reputation, and indeed begs the question of what happens to any long-dead forgotten genius after they’ve been rediscovered.

Among the symptoms of Dadd’s illness – which sounds today like a form of schizophrenia – were delusions of persecution and the receipt of messages from the Ancient Egyptian deity Osiris. Dadd was commanded to kill his father (or the demon who it appeared to him had taken his place) and did so with efficiency in the summer of 1843, not long after returning from his tour. After an equally well planned escape to France, the artist was eventually admitted to the Criminal Lunatic department of Bethlem Hospital in Lambeth (now the Imperial War Museum) and it was here that he painted the Fairy Feller. According to the inscription on the back of the canvas it took him nine years to complete, although Dadd qualifies this claim with “quasi” (“sort of”) which may mean he only worked at it on and off between 1855 and 1864.

It is an exhaustingly complex image, with a substantial cast of characters, none of whom are doing much with the exception of the “feller” himself who is about to hew a hazelnut in half in order to provide the diminutive queen of the fairies, Mab, with a new chariot. Dadd’s starting point was evidently Mercutio’s teasing speech in Romeo and Juliet in which he imagines in excruciating detail the nightly wanderings of Mab as she seeds dreams in sleepers’ heads, nocturnal visions in which suppressed ambitions and desires reveal themselves. Dadd’s inscription further informs us that the picture was painted for the Steward of Bethlem, George Henry Haydon, and in a long poem (or at least rhymed catalogue) which the artist wrote in 1865, he gives a kind of cast-list as well as offering an account of how the picture came to be painted. It was apparently Haydon who suggested some “verse about the fairies” as a “point from which to throw” – presumably the Mercutio speech which may have been intended by the Bethlem official as a means of encouraging Dadd to revisit his early life before illness had struck, when he had made his reputation as a painter of Shakespearean fairy subjects. Victorian psychiatrists were in any case fond of writing on the “cases” described by the Bard, and Charles Lamb observed how, despite the extravagant imaginative leaps of his fairy scenes, Shakespeare himself presented a kind of inverse monomania, maintaining the thread of sanity even through the most outlandish journeys of the mind.

Having received the commission for a new fairy painting from Haydon, however, Dadd says inspiration failed to materialise. He took the idea of spiritual inspiration very literally, seeing indeed the work of spirits in all human endeavour. Individuals and entire cultures may aspire to noble achievements, but the help or hindrance of the spirit world was what counted and its genii were not inclined to submit themselves to human service for long. “What’s the use of attempting the enlightenment?” asked Dadd in some notes written in the 1850s. “What a number of times the destroying angel has triumphed over the different nations of the earth – sucking them up & knocking them down”. And equally for an artist seeking to pin down their genius and compel it to answer: “What a clever angel the genius of painting must be to escape from all these hot pursuits … but once free, not all the arts of any old fellow I suppose can lure back the pretty bird to its own disgrace and bondage.” Dadd’s theory of art was thus thoroughly pessimistic. The public were a waste of time, and “one might fancy pictures are like monks secluded from and very little noticed by the world so that after all what matters about its quality except to the few, the initiated”. This might at least allow that Haydon may have been a worthwhile patron, but as for the artist himself, “what more slavish than painting, what more hopeless?” So when seeking to make a beginning of the Fairy Feller, Dadd’s only strategy upon realising that “Fancy was not to be evoked / From her etherial realms” was to accept his passive role, to entirely empty his mind: “I thought on nought – a shift / As good perhaps as thinking hard.” Finally the method succeeded: “Indefinite, almost unseen, / Lay vacant entities of chance” and gradually the “Design and composition” evolved “Without intent”. Dadd’s description of the painting, which he styled Elimination of a Picture and its Subject, thus has a curious sense of disavowal about it, as if saying who is in it is all he can do, their significance being beyond his explanation. When Dadd comes to note the head of a man wearing a conical red cap, poking out of the landscape in the top-left of the picture, he tells us that “Of the / Chinese Small Foot Societee, He’s a small member. But / if Confucius sent him Now I can’t remember.”

The characters of the Fairy Feller are mainly arranged in pairs and clusters. A group of men watch the feller intently while over the lead actor’s head is the Patriarch with epic beard, along the elongated brim of whose crown cavort a troupe of dancers apparently in Spanish costume, and indeed Dadd observes that “One is / dressed like to Duvernay”, that is Pauline Duvernay, a flamenco dancer famous on the stages of 1830s London. On either side of the Patriarch are pairs of maids and gallants, all showing an exaggeratedly gendered leg. Above the Patriarch are Oberon and Titania – rival monarchs to Mab who waits for her new chariot just below them to the left. She is, as Mercutio had described her, microscopic and yet painted by Dadd with an entirely convincing series of miniaturised impressionist touches. In the upper-left of the painting strange creatures summon further witnesses to the great moment of the splitting of the nut, and then Dadd offers – in the sequence of seven figures along the top of the picture – a version of the counting rhyme whereby boys allowed fate to choose them a profession, or girls a husband: soldier, sailor, tinker, tailor, ploughboy, apothecary, thief. If the Fairy Feller were a work intended for critical interpretation, which it probably was not, then we might talk of the suspended action with which the seed was to be split; the deferred moment of sex; the mutual isolation of the groups of figures suggesting the impossibility of generating a family or a community; and we might connect these themes to Dadd’s awareness of his own position as a long-stay patient in London’s high-security lunatic asylum where, “shut out from nature’s game” and “banished from nature’s book of life, because some angel in the strife had got the worser fate”, his lot was “in a paradise of fools [to] contented live.” But Dadd knew, given the workings of spirits, angels and fate, that autobiography was a vain fiction, and we should be wary of assuming that his most famous picture must somehow be his personal testament.

The Fairy Feller became Dadd’s most famous work because, in 1963, it entered the Tate collection where it was soon a popular favourite. It was presented to the Gallery by the then elderly poet Siegfried Sassoon, who had himself been given it by his mother-in-law, the daughter of the vastly wealthy connoisseur Alfred Morrison whose encyclopaedic collections included several Dadds. Sassoon had a special interest in the artist, having befriended, in the trenches, three brothers who were the grandsons of Richard Dadd’s elder brother. The Fairy Feller was presented to the Tate “by Siegfried Sassoon in memory of his friend and fellow officer Julian Dadd, a great-nephew of the artist, and of his two brothers who gave their lives in the First World War”, a dedication which always still accompanies the painting today. Sassoon of course had yet further personal reason for taking an interest in Dadd, having himself been a patient at Craiglockhart outside Edinburgh which functioned during the War as a hospital for shell-shocked officers.

The arrival of the Fairy Feller at the Tate, allowing Dadd a substantial audience for the first time since the 1840s, could not have been timed better if Sassoon had planned it (which he hadn’t: he donated the picture to a public collection having taken fright at the underhand tactics of an art dealer keen to relieve him of it). This was the period during which a new intellectual consensus was fomenting against the inherited system of nineteenth-century asylums, a consensus embracing everyone from the radical historian of psychiatry Michel Foucault to Enoch Powell, then British Secretary of State for Health. Dadd, having been more or less (if never completely) forgotten since the onset of his illness, now appeared something of a hero – a brave survivor of a vicious system which (so went the new story) locked away all those with whom the Victorians could not cope, which was to say many. Dadd appeared as the dark unconscious which underlay mainstream Victorian painting with its floppy maidens (Dadd contrarily had a penchant for sturdy women) and limp-wristed draughtsmanship (Dadd’s taught line was admired by some critics even when the world at large had forgotten him). The notorious magazine of Sixties counter-culture, Oz, ran a spread on the artist in 1971 and in 1974 Freddie Mercury used text from the Elimination poem for lyrics to a song titled the Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke which appeared on Queen’s second album.

But also in 1974 there appeared the results of a more sober, academic approach to Dadd. Patricia Allderidge took up the new post of archivist to the ancient Bethlem Hospital in the late 1960s and was able to recover much of Dadd’s forgotten biography and oeuvre, publishing her findings in the still indispensible catalogue to an exhibition devoted to the artist at the Tate. At this point, in retrospect, it seems the romanticised “anti-psychiatry” Dadd on one hand, and on the other the history of Dadd written from within the hospital itself, effectively cancelled one another out. At least, only the slightest amount of new research was published on the artist for decades after 1974. There seemed nowhere he might confidently be placed in the history of either art or psychiatry. So: how to deal with a long-dead forgotten genius once they’ve been rediscovered? If the talent in question never fitted in when alive, there’s little chance a permanent plinth in the pantheon of their field will be found for them even once posterity has handed them their posthumous prize. Once the ghost is raised from obscurity, where can we lay it down again?

Richard Dadd 1817-1886

- Richard Dadd was an English artist of the late nineteenth century, known for his fantastic subjects. He went mad.

Although there are a number of sites on the Web that mention Dadd in one context or another, none offers a view of Dadd the historical figure and Victorian painter. This site exists for that purpose.

Dadd The Historical Figure

Richard Dadd was born, the fourth of seven children, to Robert and and Mary Ann Dadd, in the town of Chatham, in Kent, on August 1, 1817. As a child, Richard attended The King's School at Rochester, where he developed a taste for classics and Shakespeare that stayed with him throughout his life. Although little of his work from this period survives, Allderidge has him sketching seriously at 13.In 1834, when Dadd was eighteen, his family moved to Suffolk Street, Pall Mall, in London, and Richard's father took up work as a carver and bronzeworker in the near-by Haymarket. Robert Dadd's work put his family in contact with contemporary artists and art patrons, and Richard may have received informal tutorials from some of his father's associates before he applied and was admitted to the Royal Academy in December of 1837 at age 20.

At the Academy, Dadd became friends with John Phillip, who was subsequently to marry Richard's sister Mary Elizabeth, and William Powell Frith (1819-1909), who was subsequently to play a significant role in Victorian genre painting and sontemporary social documentation. Later, this circle was expanded to include Augustus Egg, Harry Nelson O'Neill, Alfred Elmore, Edward Matthew Ward, Thomas Joy and William Bell Scott. This group was, in one form or another, known as the Clique in contemporary artistic circles, and frequently met in Dadd's rooms in Great Queen Street.

While at the Academy, Dadd won three silver medals for draughtmanship, and began exhibiting during his first year at the Academy, in the British Artists' Association. During 1840 and 1841, he bagn to work on Shakespeare illustrations in earnest, and in 1842, he exhibited a version of one of his greatest early works, Come Unto These Yellow Sands at the Royal Academy Exhibit.

That same year, he received a commission to provide illustrations for Samuel Carter Hall's Book of British Ballads (London: Jeremiah How/Vizetelly Brothers and Co.), which he executed on woodblocks. At roughly the same time, he undertook to decorate the interior of 26 Grosvenor Square for Lord Foley with scenes from Tasso and Byron. In July of 1842, Richard accompanied his patron, Sir Thomas Phillips, on an extended Grand Tour of Europe and the Middle East. They crossed from Dover to Ostend on July 16, and within the first month had visited the Rhine Valley, Lake Maggiore, the Bernese Alps, Venice (where Dadd spent time studying Veronese and Tintoretto), Bologna and Alcone. From Alcona, the two sailed via Corfu to Patras and on to Athens. From Athens, they visited Smyrna and Constantinople, returning to Symrna in late September of 1842. There, Phillips received a brief from the British ambassador to Turkey to visit the Castle of St. Peter in Bodrum, which he and Dadd did, apparently with a view to beginning negotiations for the purchase of the marbles from the tomb of Mausolus there.

Portrait of Sir Thomas Phillips in Eastern Costume, Reclining (1842)

Portrait of Sir Thomas Phillips in Eastern Costume, Reclining (1842) Dadd and Phillips traveled back down the Nile to Alexandria at the end of December. From Alexandria, the two men sailed to Malta and then on to the west coast of Italy, where Dadd began suffering from various kinds of more or less paranoid delusions of pursuit, and became increasingly violent toward Phillips. In Rome, Dadd experienced an incontrollable urge to attack the Pope during one of his public appearances, and by the time the two reached Paris in April or May of 1843, Dadd's symptoms became so acute that Phillips was no longer able to explain Dadd's behavior as exhaustion or sunstroke. Dadd left Phillips in Paris in late May, and returned to London.

Dadd's later commentary on this period of his life is instructive:

| On my return from travel, I was roused to a consideration of subjects which I had previously never dreamed of, or thought about, connected with self; and I had such ideas that, had I spoken of them openly, I must, if answered in the world's fashion, have been told I was unreasonable. I concealed, of course, these secret admonitions. I knew not whence they came, although I could not question their propriety, nor could I separate myself from what appeared my fate. My religious opinions varied and do vary from the vulgar; I was inclined to fall in with the views of the ancients, and to regard the substitution of modern ideas thereon as not for the better. These and the like, coupled with an idea of a descent from the Egyptian god Osiris..." (quoted in Allderidge, pp22-3). |

| Walpurgis Night, The Piper of Neisse, The Devil's Bridge (1842) |

Essentially, Dadd had become convinced that he was being called upon by divine forces (usually Osiris) to do battle with the Devil, who could assume any shape he desired and was incarnate all around him. Plagued by this fixation, Dadd continued working and living in Newman Street, where he subsisted largely on hard-boiled eggs and ale. Dadd's brother George was at this time also showing signs of mental illness, and Richard's father, although maintaining publicly that nothing was wrong with Richard, had Alexander Sutherland of St. Luke's Hospital examine Richard: Sutherland concluded that Dadd was non compos mentis.

In spite of this diagnosis, Robert Dadd accompanied Richard on a trip to Cobham on August 28, 1843, during which Richard had promised to "disburden his mind" to his father. The two traveled down to Cobham, ate dinner in a local inn, and then walked out into the countryside. At abut 11:00 PM, near a chalk pit called the Paddock Hole, Dadd attacked his father with a knife and razor, and killed him.

Richard left Cobham immediately after killing his father, heading to Dover, where he boarded a ship for Calais.

Robert Dadd's body was discovered on Tuesday morning, and the police were called in. There is some indication that they feared Richard Dadd dead as well: they searched for Richard in the Cobham area. When Richard's brother arrived at the crime scene, he immediately assumed Richard had killed his father, and Richard's description was sent to the Metropolitan Police. Dadd's rooms in Newman Street where searched, and the eggs and ale fetish was discovered, along with sketches of Richard's friends and associates, each with a slashed throat.

Meanwhile, Richard had been detained in Calais by the douaniere, released and left to change his bloodstained clothes in an inn in Calais. From Calais, he travelled to Paris, during which trip he attempted to cut the throat of a fellow traveler. He was taken into custody in Montereau, where he identified himself as Richard Dadd and confessed that he had murdered his father. From Montereau, he was moved to the Clermont asylum at Fontainebleau, where a search of his person revealed a list of people "who must die": his father's name was at the top of the list.

Dadd remained in Clermont until late July of 1844, when he was returned to England for a hearing in Rochester. Dadd pled guilty and was sentenced to removal "to a place of permanent safety without coming to trial" (Greysmith, pp. 62). Dadd's twenty-seventh birthday had just passed.

That place was Bethlem Hospital's crimimal lunatic department: the hospital that gave bedlam its origin and resonance. Dadd was to remain in Bethlem Hospital until July of 1864: a period just under 20 years. Here he did his most remarkable work, including The Fair Feller's Master-Stroke, Contradiction. Oberon and Titania, and Portrait of a Young Man. William Michael Rossetti, the brother of the poet Christina Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite founder Dante Gabriel Rossetti, visited Bethlem during this period and recorded his impressions of Dadd at this time:

- I saw the ill-starred painter who was sitting with two or three others in a large airy room, having beside him a mug of beer or some other refreshment. His aspect was in no way impressive or peculiar, he seemed perfectly composed, but with an undercurrent of sullenness.

Sketch to Illustrate the Passions: Agony -- Raving Madness (1854)

Dadd The Painter and Illustrator

I am not competent to evaluate Dadd's work, except to say that (a) it infuriates me that people refer to Dadd as a "fairy painter" (something a review of his canon would never sustain, on a count alone) and (b) I never tire of looking at his paintings.Dadd's work does seem to be unfamiliar to most writers on Victorian art. Julian Treuherz's summary of Dadd in his Victorian Painting seems a fairish example of the typical position on Dadd's contributions to the canon:

- ...in the early 40s, [Dadd] exhibited subjects from A Midsummer Night's Dream and The Tempest, noteworthy for their delicacy of touch and supernatural lighting effects....[After his detention]Dadd was extremely fortunate in being attended by sympathetic doctors who encouraged him to paint. Isolated form the world outside and from new developments in art, he fell back on the themes of his sane period, historical and literary subjects, recollections of the Middle East, portraits and fairies. The body of work he produced after he went mad is often bizarre and puzzling, but even in his disturbed state he painted with a clarity of form which reflects Nazarene influence....[his] most extraordinary achievement is the enigmatic The Fair Feller's Master-Stroke (1855-64), a hallucinatory vision of fantastic creatures, seen as if with a magnifying glass through a delicate network of grasses and flowers...(Treuherz, pp. 54-55).

I wrote, "what he wanted to paint" but perhaps I should say what he was compelled to paint. Reviewing his work in either Allderidge or Greysmith, any sensitive viewer is immediately struck by several recurring features of Dadd's work that are not "bizarre and puzzling" but suggestive of strong compulsions.

Crazy Jane -- detail (1885).

Crazy Jane -- detail (1885). (Small full size or larger version -- 1.2 MB)

Dadd In Contemporary Culture

- The Tate (possibly the world's greatest museum) has an article in the latest issue of its TATE ETC magazine on Orientalist painting (that peculiar Victorian imperialist vice), and Dadd figures in the piece. Links are included to the Dadd pieces in the Tate collections.

I don't know quite what this BBC-hosted thing on Richad Dadd is, but I dig it.

Dadd's fairy paintings in the context of the Victorian fairy painting subgenre.

Dadd gets blog'd: a serious-minded blog entry on Dadd.

Dadd has made it to Wikipedia, which is I suppose a kind of Internet canonization.

His paintings and drawings still appear on the market from time to time.

You can actually buy a fewDadd prints from AllPosters.Com.

Neil Gaiman, the creator of the Sandman comic, is apparently a Dadd fan.

Dadd Paintings, Drawings and Illustrations On The Web

- The Closet Scene From Hamlet (1840: oil on canvas)

Jerusalem from the House of Herod (watercolor)

Puck (1841: oil on canvas).

Titania Sleeping (1841: oil on canvas)

Portrait of Sir Thomas Phillips in Eastern Costume, Reclining (1842: watercolor)

Walpurgis Night, The Piper of Neisse, The Devil's Bridge (1842: ink)

Come Unto These Yellow Sands (1843: oil on canvas)

Caravan Halted By The Sea Shore (1843: oil on canvas)

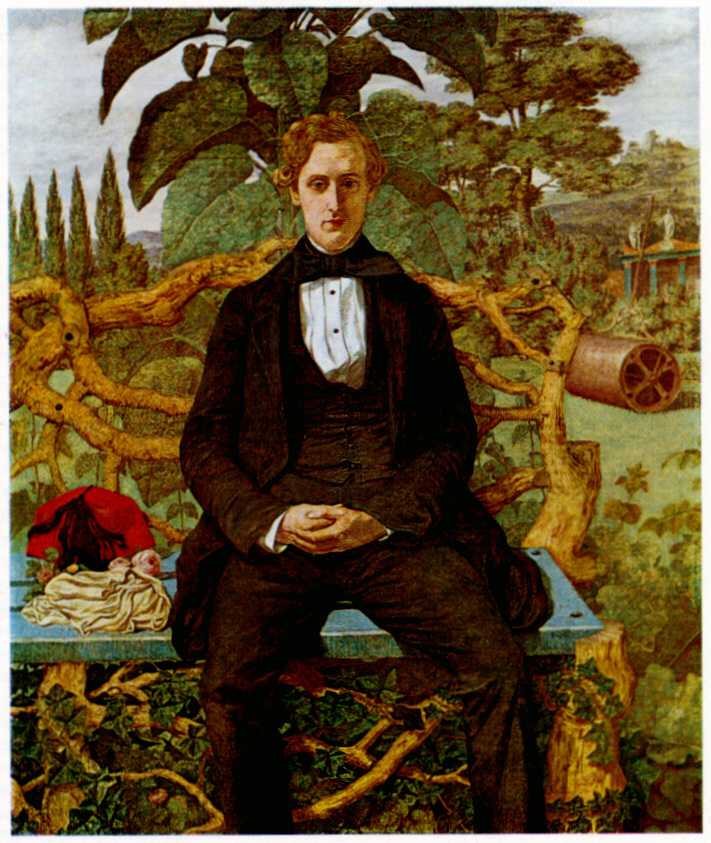

Portrait of a Young Man / Dr. Charles Hood (1853: oil on canvas)

Sketch to Illustrate the Passions: Love, Agony -- Raving Madness, Melancholia, and Senility (courtesy of Sim Fine Art).

David Sparing Saul

Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1854-8: oil on canvas) -- arguably superior to the FFMS.

Crazy Jane (1855: watercolor) -- a marvelous work, with (as someone pointed out to me) a man as Dadd's model

The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke (1855-64: oil on canvas) and the painting with Dadd's poetic explication thereof. If you are ever in the Tate in London, and they have FFMS out, don't miss it.

Works On or Mentioning Dadd

- Allderidge, Patricia. The Late Richard Dadd: 1817-1886 London: The Tate Gallery [n.d.] By far the best book for a view of Dadd's work. Allderidge, Patricia. Richard Dadd. London: Academy Editions, 1974.

De Saint Pierre, Isaure. Richard Dadd - His Journals Ellis. 1984.

Greysmith, Richard. Richard Dadd: The Rock and Castle of Seclusion: London: Studio Vista, 1973. The most sensitive and coherent of the Dadd biographies.

MacGregor, J.M. The Discovery of the Art of the Insane. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Treuherz, Julian. Victorian Painting. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

Last updated 5-24-07 by Marc Demarest (marc@noumenal.com)

Richard Dadd, Contradiction

A condensed excerpt from: The Christie’s Sale Catalogue 1992

Richard Dadd is a unique phenomenon in British art, perhaps in Western art in general. A fairly late product of the Romantic Movement, he gave a new dimension to Romanticism’s determined pursuit of the irrational. Insane for nearly two thirds of his life, he was able, like a traveller with tales of a fabulous country, to send back reports of his mental terra incognita thanks to the miraculous preservation of his talent under the condition of his madness.

Contradiction, was painted in Bethlem Hospital, Southwark (part of which is now the Imperial War Museum) during the years 1854-8. It saw him return to A Midsummer Night’s Dream as muse, representing Oberon and Titania at the moment of their quarrel over Titania’s refusal to give up here Indian changeling boy to be Oberon’s page.

The prodigality of Dadd’s imagination in this work seems to be inexhaustible, and besides the obvious inventiveness of the design and of the main characters and their costumes, a host of tiny creatures teem through the foreground and background.

Dadd is seen working on the picture in the only known photograph of him in Bethlem (above). The whole design has been laid in, and he is painstakingly completing it, detail by minute detail, from the lower right corner upwards. Evidence of this method is still traceable in some of the larger leaves, where sections painted at different times show slight variations in colour.

Technically the work is an astonishing tour de force. However ‘mad’ Dadd may have been, it certainly in no way confused his drawing or handling of paint; on the contrary, the painting has a positively surreal clarity. It remains in a superb state of preservation, never having been re-lined and still possessing the original oval stretcher seen in the photograph.

Visit Wikipedia for more on Richard Dadd. Visit Bethlem Museum for more information on the hospital.

Text adapted from the Christie’s Sale Catalogue.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar