Slika kao filozofija slike.

tanseypictures.tumblr.com/

In Tansey's paintings modern art serves as an arena for the visualization of the invisible mechanics of ideology - David Joselit

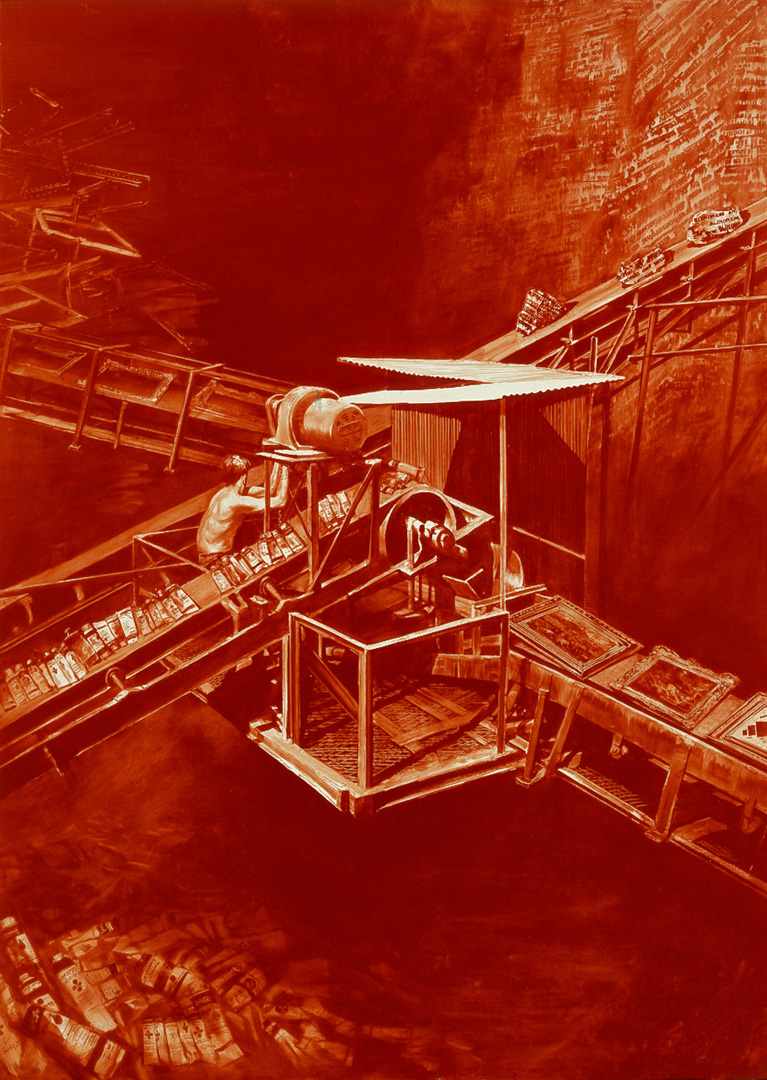

The dense imagery that permeates Mark Tansey's canvases can be sourced to a trove of visual material that the artist has collected over the years. This includes his own photographs, as well as clippings from magazines, journals and newspapers. Tansey begins his creative process by stretching, rotating or cropping forms, combining images, and photocopying them over and over again until he produces a collage that can serve as a preliminary study for his paintings.

Tansey's work typifies the complexity of our age, when certainty seems more elusive than ever. In his paintings, it is difficult to determine whether east is west, up is down, left is right, or good is evil. The literal is the figurative, and the figurative is literal. Tansey embraces this ambiguity and invites the viewer to participate in a visual and metaphorical adventure.

https://www.gagosian.com/artists/mark-tansey

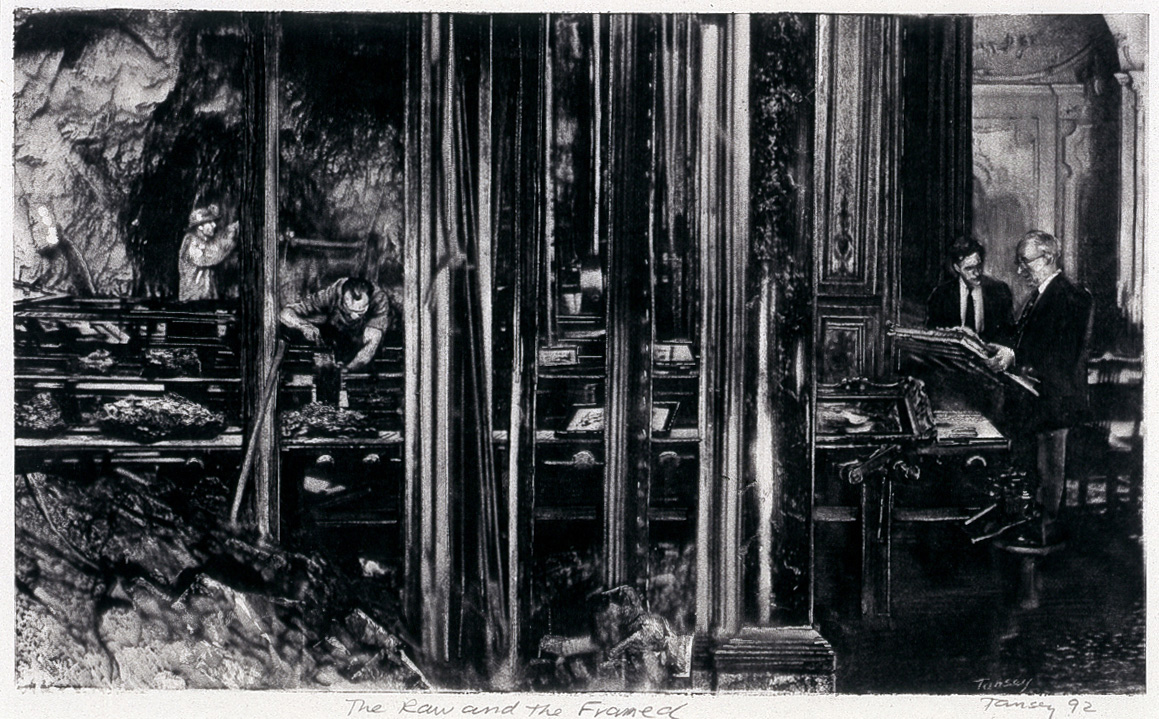

Mark Tansey’s approach to painting reflects a deep knowledge of art, as many of his motifs are either lifted from historical paintings or depict important artists and philosophers. Each of Tansey’s paintings is a carefully calculated allegory about the meaning of art and the mystery of the human impulse to make images. Rendered in a single hue, Tansey’s canvases achieve a precise photographic quality through a complex process involving the washing, brushing, or scraping of monochromatic paint into gesso. Tansey’s subjects are fantastic, sometimes surreal scenes in which intellectual theories about art are dramatized, often complete with portraits of characters drawn from the discipline’s history.

Forward Retreat, 1986, describes the slipperiness of perception and questions the validity of innovation in art. The central image of horseback riders is painted as a reflection on water. The riders, all outfitted in uniforms of Western powers (American, French, German, and British), represent the nationalities of artists who came to dominate twentieth-century art history. They are seated backward on their horses, focused on a distant receding horizon, and are oblivious to the fact that their steeds trample on the crushed ruins of myriad pottery and objets d’art. With typically dry humor, Tansey implies two conclusions: that art progresses on the ruins of its past and that art making is propelled in part by unconscious forces.

Arrest, 1988, also reflects on art’s ambivalent relationship with history. In the picture, a group of people is almost completely absorbed by the shadow of an ancient statue. From the darkness, the limbs and objects that emerge suggest an auto body shop, a place where vehicles are fixed with the hope of escaping the shadow across the expanse of desert. Tansey has described this painting as a meditation on history and the bind it places on artists. While on one hand, art seeks to be truly revolutionary, on the other hand, art is sustained and nourished by the past. Ultimately, the painting offers the idea that an escape from history is possible but inherently dangerous.

https://www.thebroad.org/art/mark-tansey

The Bricoleur’s Daughter, 1987

Oil on canvas

68 x 67 in.

Collection Emily Fisher Landau, New York

Jacques Derrida argued that Western thought is founded on the nature/culture divide. He posits two possible means of critiquing the tradition to which one belongs: stand “outside” of Western philosophy (Derrida suggests that this is impossible), or work with the tools Western philosophy provides, while acknowledging their limitations, to deconstruct it. He calls this second method bricolage, after the anthropologist and theorist Claude Lévi-Strauss, and he or she who creates bricolage the bricoleur. Derrida contrasts the bricoleur with the engineer, who can supposedly stand outside of philosophy and build a new one from the ground up without the flaws of the old. Derrida writes in his essay, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,”

So Tansey is himself a bricoleur, working with the medium of painting to deconstruct the discourse to which he belongs while recognizing the limitations of his medium, or, indeed, of the scopic regime in which that medium is situated.

Tansey works with the assumption that Derrida says is the foundation Western thought—the nature/culture divide—to critique the very same assumption. Heidegger’s earth/world pair is apparent throughout Tansey’s work, but Tansey is critical of that divide just as he is critical of the scopic regimes, the world pictures, that are derived from it.

Oil on canvas

68 x 67 in.

Collection Emily Fisher Landau, New York

Jacques Derrida argued that Western thought is founded on the nature/culture divide. He posits two possible means of critiquing the tradition to which one belongs: stand “outside” of Western philosophy (Derrida suggests that this is impossible), or work with the tools Western philosophy provides, while acknowledging their limitations, to deconstruct it. He calls this second method bricolage, after the anthropologist and theorist Claude Lévi-Strauss, and he or she who creates bricolage the bricoleur. Derrida contrasts the bricoleur with the engineer, who can supposedly stand outside of philosophy and build a new one from the ground up without the flaws of the old. Derrida writes in his essay, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,”

If one calls bricolage the necessity of borrowing one’s concepts from the text of a heritage which is more or less coherent or ruined, it must be said that every discourse is bricoleur. The engineer, whom Lévi-Strauss opposes to the bricoleur, should be the one to construct the totality of his language, syntax, and lexicon. In this sense the engineer is a myth.Tansey's Bricoleur’s Daughter is working with the tools she has, the paintbrushes and flashlight of her father or mother, to create something new and deconstruct the discourse to which she belongs. The shadows on the wall are very much the shadows of Plato’s cave, as are, we are reminded, the paintbrushes’ other products: paintings.

So Tansey is himself a bricoleur, working with the medium of painting to deconstruct the discourse to which he belongs while recognizing the limitations of his medium, or, indeed, of the scopic regime in which that medium is situated.

Tansey works with the assumption that Derrida says is the foundation Western thought—the nature/culture divide—to critique the very same assumption. Heidegger’s earth/world pair is apparent throughout Tansey’s work, but Tansey is critical of that divide just as he is critical of the scopic regimes, the world pictures, that are derived from it.

Doubting Thomas, 1986

Oil on canvas

65 x 54 in.

Doubting Thomas is a play on Caravaggio’s 1602 The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. The man inserts his fingers into the crack in the road as if he does not believe it exists, as Thomas does with Jesus’ wound. The scale of geologic time is beyond his human comprehension, just as Jesus’s resurrection is a divine event beyond Thomas’s human understanding.

For the knowing reader or viewer, Thomas’s doubt in Jesus’s resurrection appears absurd. The man is standing right before him, yet still Jesus must guide Thomas’s finger into his wound for verification. For any viewer who has studied earth science in middle school, Tansey's Doubting Thomas’s doubt is also absurd.

In class, we debated whether or not we “live in the universe.” Tansey’s doubting Thomas seems skeptical as to whether he lives on the Earth. That is, in his mind, he lives in the world, the human world of cars and roads, not on a geologically active planet with active fault lines. The road and the car represent the human world, the fault line, the earth:

Just as Caravaggio’s painting renders Thomas’s doubt as absurd, so does Tansey’s painting render the artificial distinction between earth and world, nature and culture, absurd. Can anyone really doubt that the earth undergoes geologic change? Only if one lives only in the world, and not also on the earth.

Oil on canvas

65 x 54 in.

Doubting Thomas is a play on Caravaggio’s 1602 The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. The man inserts his fingers into the crack in the road as if he does not believe it exists, as Thomas does with Jesus’ wound. The scale of geologic time is beyond his human comprehension, just as Jesus’s resurrection is a divine event beyond Thomas’s human understanding.

For the knowing reader or viewer, Thomas’s doubt in Jesus’s resurrection appears absurd. The man is standing right before him, yet still Jesus must guide Thomas’s finger into his wound for verification. For any viewer who has studied earth science in middle school, Tansey's Doubting Thomas’s doubt is also absurd.

In class, we debated whether or not we “live in the universe.” Tansey’s doubting Thomas seems skeptical as to whether he lives on the Earth. That is, in his mind, he lives in the world, the human world of cars and roads, not on a geologically active planet with active fault lines. The road and the car represent the human world, the fault line, the earth:

The world grounds itself on the earth, and earth juts through world. But the relation between world and earth does not wither away into the empty unity of opposites unconcerned with one another. The world, in resting upon the earth, strives to surmount it. As self-opening it cannot endure anything closed. The earth, however, as sheltering and concealing, tends always to draw the world into itself and keep it there. (Heidegger, 172)The modern human world takes its triumph over the earth as given. In a way, this triumph is actual—Earthrise or The Blue Marble are the literal manifestations, or culmination perhaps, of the modern world picture, the Whole Earth. But the earth never truly disappears from beneath the world, and attempts to erase the earth may result in both the earth’s and world’s near-destruction.

Just as Caravaggio’s painting renders Thomas’s doubt as absurd, so does Tansey’s painting render the artificial distinction between earth and world, nature and culture, absurd. Can anyone really doubt that the earth undergoes geologic change? Only if one lives only in the world, and not also on the earth.

Purity Test, 1982

Oil on canvas

72 x 96 in.

Chase Manhattan Bank

The painting that inspired this exhibit.

The Native Americans test the purity of Spiral Jetty, an apparent intrusion into their untouched landscape. But the purity of our conception of Native Americans itself is tested, and we remember that the figures depicted are drawn from problematic traditions of stereotypes.

Shapiro writes,

Oil on canvas

72 x 96 in.

Chase Manhattan Bank

The painting that inspired this exhibit.

The Native Americans test the purity of Spiral Jetty, an apparent intrusion into their untouched landscape. But the purity of our conception of Native Americans itself is tested, and we remember that the figures depicted are drawn from problematic traditions of stereotypes.

Shapiro writes,

Surely the title of Mark Tansey’s Purity Test, another refraction of the spiral (and, I would argue, of the essay and the film) is highly ironic. This is not because Smithson was aiming at a pure art, free from the constraints of the New York art world, but rather because everything about this image is decidedly impure: the representational character of the painting, which violates the modernist imperative of exploring the lateness of the picture plane, the anachronism of these Native Americans encountering the spiral that was built in 1970, and the blatant depiction of these spectators in costume and poses borrowed from the now antiquated style of the painters of an illusory heroic American past. (Shapiro, 7-8)

For Tansey, Spiral Jetty is a work that worlds, but it is, through the eyes of the Native Americans, not natural. The ideal Native American does not need a work to world, to grapple with the earth and bring it out of obscurity, his relationship with the earth is untainted. But we know that this ideal Native American never existed but in the minds of nostalgic Westerners. Just as Spiral Jetty confuses the boundary between nature and artifact and reveals that distinction to be a spurious one. Purity Test has what is to a Westerner, who depends on the existence of the pristine earth apart from the world even as the world attempts to subsume the earth, a bleak take—what purity is there to be tested?

Triumph Over Mastery, 1986 (click here for higher resolution scan)

Oil and pencil on canvas

59 7/8 x 144 ¼ in.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

In this post-apocalyptic landscape a la Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” a mother and her two sons appear to be taking a walk through a ruin. From a distance, the figures appear to be wearing the garb of a future civilization reduced to pre-Common Era technology. The mother’s clothing matches the flowing raiment of the statue opposite her in the left of the painting, in a temporal and compositional mirroring: the woman of the distant future wears the clothing of the distant past. But, on closer inspection, the viewer sees that the mother is wearing a modern dress and even has a pair of glasses sitting on her head. The two boys are wearing t-shirts and shorts. The figures could be an American family from any time since 1950.

Time is confused in this landscape. Contemporary figures occupy the distant future, which is occupied by artifacts of the distant past. The landscape is itself also confused. The remnants of the temple, or whatever monument now lies broken before us, do not enclose God. They do not bring the ground on which they lie up out of obscurity. They do not “make visible the invisible space of the air” (Heidegger The Origin of the Work of Art, 169). Beyond the foreground, ruins stretch to the horizon in a vast plain, without contrast and without the ability to create contrast. There is no sheltering here, no “emerging and rising in itself,” no physis (Heidegger, 169). The earth here depicted is only earth in its grossest form, that which lies beneath our feet.

The “triumph” here is not over humanity’s “mastery” of nature, but over mastery altogether. For Heidegger, world and earth are eternally in conflict; neither can master the other. Heidegger writes,

The world to which the works that are now ruins belonged has been reduced to rubble.

But modern figures stand in the rubble. A boy stands on a toppled pillar as if on a playground structure. The sprawl of America’s Inland Empire is just as undifferentiated as the ruins that stand in the background of the painting. Where in the contemporary world is Heidegger’s temple that makes visible the invisible space of the air, that in relying on the support of solid rock brings it out of obscurity, that in standing against the sea spray “brings out the raging of the sea” (Heidegger, 169)?

This destruction, and even Heidegger’s temple, is a product of a false distinction between earth and world. For Tansey, only the foolish and the faithless would assume this distinction to exist, though it is on this distinction that Western thought is founded.

Oil and pencil on canvas

59 7/8 x 144 ¼ in.

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

In this post-apocalyptic landscape a la Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” a mother and her two sons appear to be taking a walk through a ruin. From a distance, the figures appear to be wearing the garb of a future civilization reduced to pre-Common Era technology. The mother’s clothing matches the flowing raiment of the statue opposite her in the left of the painting, in a temporal and compositional mirroring: the woman of the distant future wears the clothing of the distant past. But, on closer inspection, the viewer sees that the mother is wearing a modern dress and even has a pair of glasses sitting on her head. The two boys are wearing t-shirts and shorts. The figures could be an American family from any time since 1950.

Time is confused in this landscape. Contemporary figures occupy the distant future, which is occupied by artifacts of the distant past. The landscape is itself also confused. The remnants of the temple, or whatever monument now lies broken before us, do not enclose God. They do not bring the ground on which they lie up out of obscurity. They do not “make visible the invisible space of the air” (Heidegger The Origin of the Work of Art, 169). Beyond the foreground, ruins stretch to the horizon in a vast plain, without contrast and without the ability to create contrast. There is no sheltering here, no “emerging and rising in itself,” no physis (Heidegger, 169). The earth here depicted is only earth in its grossest form, that which lies beneath our feet.

The “triumph” here is not over humanity’s “mastery” of nature, but over mastery altogether. For Heidegger, world and earth are eternally in conflict; neither can master the other. Heidegger writes,

Earth, irreducibly spontaneous, is effortless and untiring. Upon the earth and in it, historical man grounds his dwelling in the world. In setting up a world, the work sets forth the earth. This setting forth must be thought here in the strict sense of the word. The work moves the earth itself into the open region of a world and keeps it there. The work lets the earth be an earth…With the decay of the human world into ruin, the earth, too, returns to an earlier state. Work, world, builds up earth by being in strife with it, the two elevate one another in their mutual conflict. In Triumph Over Mastery, world and earth remain, but are reduced to a nearly pre-human, pre-work state—whether by war or simple entropy is unclear. Tansey’s painting follows modern attempts to place world as master over earth to their logical conclusion. Only rubble remains, the world withdrawn and decayed. Heidegger writes of a similar scenario when contemplating the fate of ancient sculptures, plays, and buildings:

The opposition of world and earth is strife. But we would surely all too easily falsify its essence if we were to confound strife with discord and dispute, and thus see it only as disorder and destruction. In essential strife, rather, the opponents raise each other into the self-assertion of their essential natures. Self-assertion of essence, however, is never a rigid insistence upon some contingent state, but surrender to the concealed originality of the provenance of one’s own Being. In strife, each opponent carries the other beyond itself. Thus the strife becomes ever more intense as striving, and more properly what it is. The more strife overdoes itself on its own part, the more inflexibly do the opponents let themselves go into the intimacy of simple belonging to one another. The earth cannot dispense with the open region of the world if it itself is to appear as earth in the liberated surge of its self-seclusion. The world in turn cannot soar out of the earth’s sight if, as the governing breadth and path of all essential destiny, it is to ground itself on a resolute foundation. (Heidegger, 171-2)

Well, then, the works themselves stand and hang in collections and exhibitions. But are they here in themselves as the works they themselves are, or are they not rather here as objects of the art industry? Works are made available for public and private art appreciation. Official agencies assume the care and maintenance of works. Connoisseurs and critics busy themselves with them. Art dealers supply the market. Art-historical study makes the works the objects of a science. Yet in all this busy activity do we encounter the work itself?

The Aegina sculptures in the Munich collection, Sophocles' Antigone in the best critical edition, are, as the works they are, torn out of their own native sphere. However high their quality and power of impression, however good their state of preservation, however certain their interpretation, placing them in a collection has withdrawn them from their own world. But even when we make an effort to cancel or avoid such displacement of works—when, for instance, we visit the temple in Paestum at its own site or the Bamberg cathedral on its own square—the world of the work that stands there has perished.

World-withdrawal and world-decay can never be undone. The works are no longer the same as they once were. It is they themselves, to be sure, that we encounter there, but they themselves are gone by. As bygone works they stand over against us in the realm of tradition and conservation. (Heidegger, 167-168)

But modern figures stand in the rubble. A boy stands on a toppled pillar as if on a playground structure. The sprawl of America’s Inland Empire is just as undifferentiated as the ruins that stand in the background of the painting. Where in the contemporary world is Heidegger’s temple that makes visible the invisible space of the air, that in relying on the support of solid rock brings it out of obscurity, that in standing against the sea spray “brings out the raging of the sea” (Heidegger, 169)?

This destruction, and even Heidegger’s temple, is a product of a false distinction between earth and world. For Tansey, only the foolish and the faithless would assume this distinction to exist, though it is on this distinction that Western thought is founded.

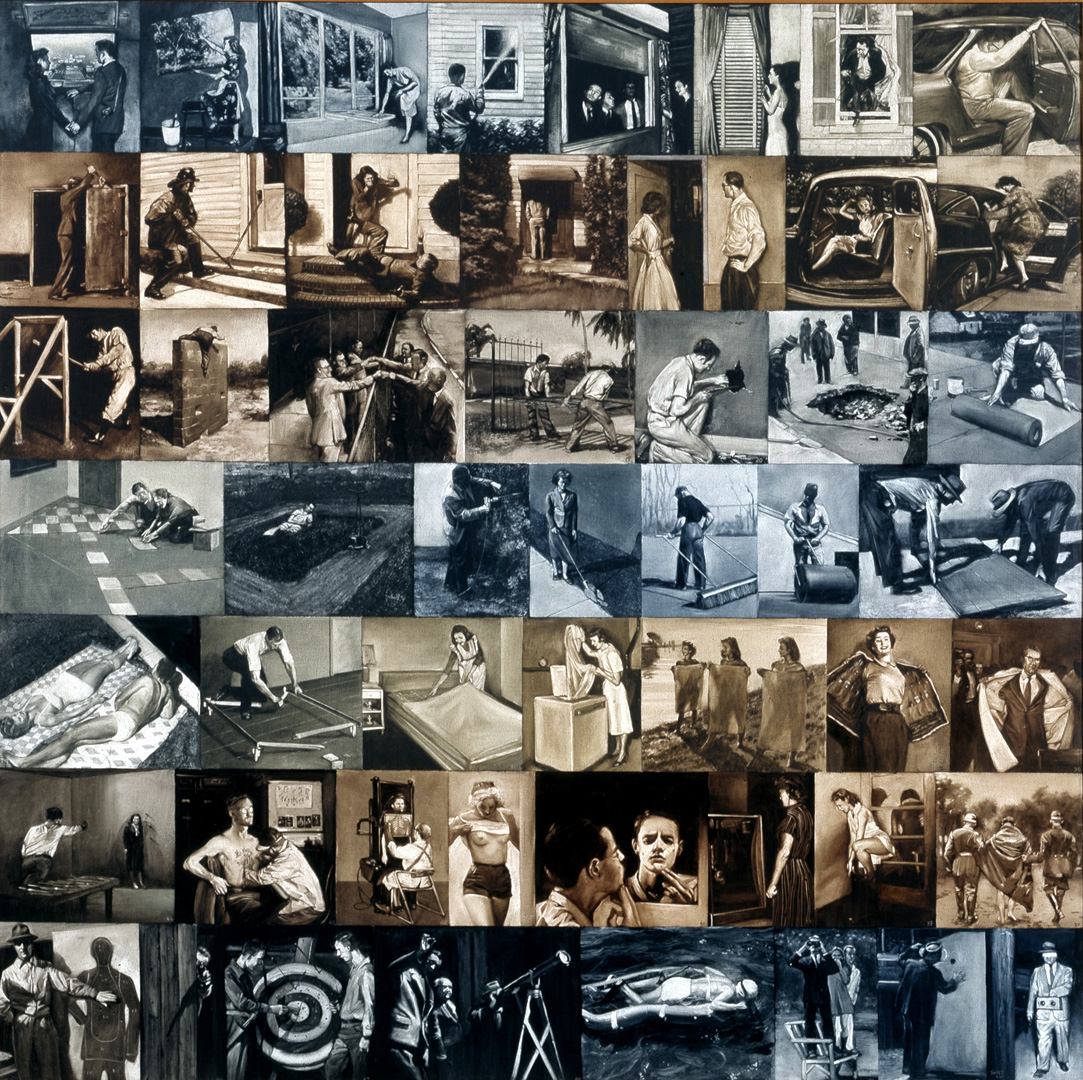

A Short History of Modernist Painting presents a storyboard of the problems and interests of painting over many decades. Mark Tansey’s interpretation of this history starts with the belief that painting is a window to, and representation of, the world, an idea long attributed to the Italian architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti. Tansey’s series of pictorial allegories shows how Alberti’s idea has been expanded and critiqued by modernism. Often in the work, references to particular artists or moments in recent art history are recognizable: Carl Andre’s tiles of metal, Jasper Johns’s target, and Chris Burden’s famous 1971 Shoot piece (portrayed here as a scene of knife throwing). Movements such as performance art, body art, minimalism, and others can be identified as well. Ultimately, Tansey demonstrates art as inclusive of painting and yet far beyond it, art as capable of using any medium and open to almost any subject.

https://www.thebroad.org/art/mark-tansey

Action Painting II, 1984

Oil on canvas

193 x 279.4 cm

Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal

Jay writes of the “eye” of Cartesian perspectivalism,

In Action Painting II, paintings are as if rendered instantly, with the immediacy of a photograph, yet still the painters add the finishing touches, or, as the figures in the right of the canvas, pause to contemplate their work. This is the “visual field from a vantage-point outside the mobility of duration, in an eternal moment of disclosed presence,” that Bryson attributes to Cartesian perspectivalism. Tansey’s many painters exemplify paradox of this “eternal moment.” The scene before them is frozen, every detail in the vapor formed by the shuttle’s exhaust incredibly clear, more clear even than the grass on the ground on which the painters stand.that eye was singular, rather than the two eyes of normal binocular vision. It was conceived in the manner of a lone eye looking through a peephole at the scene in front of it…[i]n Norman Bryson’s terms, it followed the logic of the Gaze rather than the Glance, thus producing a visual take that was eternalized, reduced to one “point of view” and disembodied. In what Bryson calls the “Founding Perception” of the Cartesian perspectivalist tradition,“the gaze of the painter arrests the flux of phenomena, contemplates the visual field from a vantage-point outside the mobility of duration, in an eternal moment of disclosed presence; while in the moment of viewing, the viewing subject unites his gaze with the Founding Perception, in a moment of perfect recreation of that first epiphany.”

Each painter captures the event in the same perspective the painting itself offers, but they omit themselves from the work. Also missing from their paintings is the American flag, a symbol that reminds us that each painter approaches the shuttle launch with a distinctly American point of view, however much they may try to efface it. (We are also reminded of Tansey’s own American eye.) Cartesian perspectivalism, in which the artist attempts to frame the scene so well that the viewer is awed by not the painting, but the scene itself, is an eye that attempts to erase its own framing. The Cartesian eye presents what it sees as natural, self-evident, real. But every photographer, every artist, is present still.

The Whole Earth can never be a truly objective world picture. The array of Action Painting II’s many identical canvasses is absurd, as absurd as the notion that from seven billion minds and twice as many eyes there can ever truly be one true Whole Earth.

tanseypictures.tumblr.com/post/69314872925/action-painting-ii-1984-oil-on-canvas-193-x-2794

Triumph of the New York School, 1984

Oil on canvas

74 x 120 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Tansey exposes the work of the New York School as not a glorification of nature, but a conquest of it. This is the world gone power-mad, the world trying to domesticate and erase the earth on which it is founded, and trying in doing so to erase its own identity as a mere world picture and finally assume the Apollonian throne.

Oil on canvas

74 x 120 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Tansey exposes the work of the New York School as not a glorification of nature, but a conquest of it. This is the world gone power-mad, the world trying to domesticate and erase the earth on which it is founded, and trying in doing so to erase its own identity as a mere world picture and finally assume the Apollonian throne.

The Monochromatic and Contradictory World of Mark Tansey

Artist Mark Tansey was born on August 2, 1949, and curatorial intern Kaitlin Morelock would love to fill you in on some information behind the artist responsible for Landscape, located in Crystal Bridges’ 1940s to Now Gallery.

Ever wondered what Tansey’s process behind his works is like? You’re undoubtedly not the only one.

Most of Tansey’s paintings offer contradictory compositions that simultaneously appear rooted in a precise realism while conveying a jumbled, visual jargon of competing images that may leave a viewer with more questions than answers relating to the composition’s origins. Tansey’s knowledge of art history remains evident throughout his work, as he often borrows imagery from famous historical works, inserting them into his own re-imagined scenes.

While Tansey was attending art school at Hunter College of the Arts in New York in the seventies, the status quo in modern art at the time was a deliberate shift away from realism and representative works. However, Tansey challenged this trend with full force. Tansey has referred to his artistic motivations as a remedy for the “death of painting” following the art world’s shift toward more Minimalist endeavors. His work relies heavily on figurative images that relate to his thorough academic and art historical knowledge, infusing his meticulous paintings with subject matter and purpose.

Tansey’s process of constructing image compositions for his paintings is perhaps one of the more interesting artistic processes I’ve encountered. He begins by selecting images from an exhaustive catalog of stockpiled material from various sources, collected by Tansey over the last several decades. Tansey selects appropriate figures, pastes them into intricately collaged configurations, and then photocopies them a number of times, manipulating the density and contrast until he is satisfied with the image, which then serves as the basis for his painting. Tansey also utilizes a self-made “color wheel” of words that allows him to create unusual and contradictory subject matter for his works (seen in the image below). The result is a comic and cleverly constructed scene that uses appropriated references to produce an entirely new and innovative image. (You can read more about this fascinating device here.)

.

Another unique feature of Tansey’s process involves the actual execution of the painting. Applying a single color over a layer of gesso, Tansey’s complex imagery is achieved through the removal of paint instead of through its application, meaning that the white seen in the works is not painted, but is rather the absence of paint that was once there. Such a process requires Tansey to work quickly because he has only about six hours before the paint dries and can no longer be manipulated. Therefore, in order to include his characteristic amount of detail, he only works on one small section at a time, moving around the painting in pieces instead of working on the entire composition at one time.

Tansey’s quirky paintings have provided, once more, a place for realism in the context of modern art, while his artistic education and style, as well as his use of imagery derived from American publications, help place Tansey as a quintessentially American artist.

- Kaitlin Morelock

- Kaitlin Morelock

https://crystalbridges.org/blog/the-monochromatic-and-contradictory-world-of-mark-tansey/

Ever wondered what Tansey’s process behind his works is like? You’re undoubtedly not the only one.

Most of Tansey’s paintings offer contradictory compositions that simultaneously appear rooted in a precise realism while conveying a jumbled, visual jargon of competing images that may leave a viewer with more questions than answers relating to the composition’s origins. Tansey’s knowledge of art history remains evident throughout his work, as he often borrows imagery from famous historical works, inserting them into his own re-imagined scenes.

While Tansey was attending art school at Hunter College of the Arts in New York in the seventies, the status quo in modern art at the time was a deliberate shift away from realism and representative works. However, Tansey challenged this trend with full force. Tansey has referred to his artistic motivations as a remedy for the “death of painting” following the art world’s shift toward more Minimalist endeavors. His work relies heavily on figurative images that relate to his thorough academic and art historical knowledge, infusing his meticulous paintings with subject matter and purpose.

Mark Tansey, B. 1949

The Innocent Eye Test, 1981

Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Mark Tansey

The Innocent Eye Test, 1981

Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Mark Tansey

Tansey’s process of constructing image compositions for his paintings is perhaps one of the more interesting artistic processes I’ve encountered. He begins by selecting images from an exhaustive catalog of stockpiled material from various sources, collected by Tansey over the last several decades. Tansey selects appropriate figures, pastes them into intricately collaged configurations, and then photocopies them a number of times, manipulating the density and contrast until he is satisfied with the image, which then serves as the basis for his painting. Tansey also utilizes a self-made “color wheel” of words that allows him to create unusual and contradictory subject matter for his works (seen in the image below). The result is a comic and cleverly constructed scene that uses appropriated references to produce an entirely new and innovative image. (You can read more about this fascinating device here.)

.

Another unique feature of Tansey’s process involves the actual execution of the painting. Applying a single color over a layer of gesso, Tansey’s complex imagery is achieved through the removal of paint instead of through its application, meaning that the white seen in the works is not painted, but is rather the absence of paint that was once there. Such a process requires Tansey to work quickly because he has only about six hours before the paint dries and can no longer be manipulated. Therefore, in order to include his characteristic amount of detail, he only works on one small section at a time, moving around the painting in pieces instead of working on the entire composition at one time.

Tansey’s quirky paintings have provided, once more, a place for realism in the context of modern art, while his artistic education and style, as well as his use of imagery derived from American publications, help place Tansey as a quintessentially American artist.

Mark Tansey (American, born San Jose, California 1949)

Still Life, 1982

Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Still Life, 1982

Oil on canvas

Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://crystalbridges.org/blog/the-monochromatic-and-contradictory-world-of-mark-tansey/

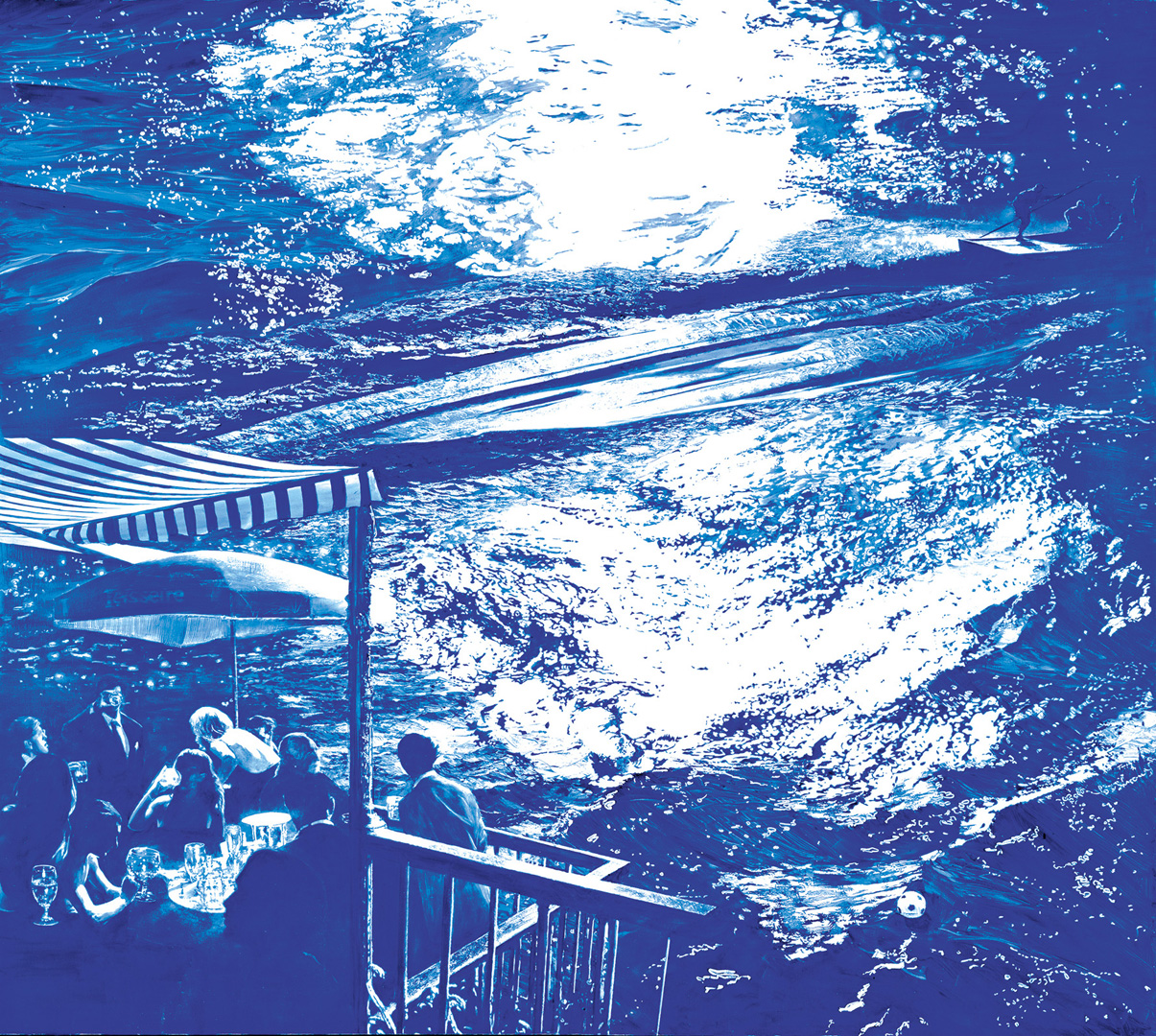

Although Mark Tansey might be-and has been-considered a landscape painter, the landscapes he constructs have little to do with nature. Tansey's landscapes are at once conventional and contradictory: they may simultaneously contain generic visions, fantastic illusions and "historical" events. These three ingredients are spliced together differently in different paintings, yielding combinations as bizarre, yet oddly probable as a gentle lake lying before a spectacular space shuttle takeoff, a classical ruin with a destroyed New York City in the distance, or a rock promontory from which Native Americans gaze at Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty.

Like the space of the mass media in which bits and pieces of information are broken loose from their historical grounding and freely recombined into novel configurations, the landscape Tansey describes is one in which radically dissimilar events and places can gracefully coexist. Although his use of grisaille reads most immediately as a reference to old photographs, it also recalls the space of film and television. And yet in spite of their metaphorical reflection on the mass media, the paintings refer to another era of art-historical pastiche: academic art of the 19th

century. Through the historical displacement which this similarity suggests, Tansey is able to reflect on the present in images clothed by the conventions of the past. As the title of one recent painting Forward Retreat implies, he is approaching modernism from both sides at once, subjecting his paintings to a kind of temporal bending.

In the process of constructing a painting, Tansey reduces a discursive field of imagery to a unified dramatic situation. He maintains extensive files of landscape or figure types drawn from magazines, newspapers and books, and often makes use of homemade charts, some in the form of rotating wheels which match up unrelated phrases drawn, from his theoretical readings. Tansey has said that his paintings "mobilize a list"-his narrative strategy involves inventing landscapes which can naturalize the coexistence of dissimilar or contradictory figures, events. In the recent painting White on White, a group of Bedouins confronts a group of Eskimos in a seemingly unified field of snow and sand, hot and cold. In this painting the artist forcibly brought two entirely unlike climates and civilizations into a single shared moment, as in the sequence of reports on the evening news. Tansey's landscape performs a sleight of hand: it depicts the collapse of historical time, of cultural difference, and yet this impossible conjunction is depicted as a visually convincing, "real" landscape.

Equally as problematic as the landscapes Tansey constructs are the people--or figures-which inhabit them. In most cases they are types or recognizable historical figures, who convey little if any psychological depth. Like character actors, their conventional roles (an American Indian, a housewife from. the '40s or '50s, or a soldier) are immediately legible The painting's drama, and its content, are derived from how these characters recombine in their shadowy world: how they are re-edited. With these figures, which are themselves virtually signs, Tansey fashions moral tales about the world of representation.

Often, time is arrested in Tansev's work. Action Painting, 1981, and Action Painting II, 1984, are ostensibly literary reinventions of Abstract Expressionism. In both works, spectacular events-a racing-car crash, a space shuttle takeoff-are the subject, within the painting, for Sunday painters working at their easels. At first reading, these works perform a fairly obvious elision of plein-air traditions-as presented in the popular guise of amateur art-and the psychological and formal rigors of high art abstraction. But underlying this collapse of high and middlebrow culture is a temporal paradox: the painters within the paintings, arranged in stock poses of artistic contemplation, have completed accurate images of an instantaneous event. Only high speed photography could capture the moments that these low-technology image-makers have constructed. The duration of their own process is contradicted by the duration of action they are painting. This leaves us with the uneasy feeling that time is discontinuous within a continuous landscape, or that time has been stopped (by painting?), and that the car and the space shuttle are as stable as the mountain and the tree.

In the recent painting Conversation, two men sit before a garden wall, and at the edge of a reflecting pool. Beyond the wall, and reflected in the pool, trees are bent over by strong winds, but the men, one calmly smoking and the other comfortably seated with legs crossed, are tranquil in the midst of the storm which surrounds them. The urgency of the weather contradicts the stasis of their visit: they are trapped in a lateral sliver of space, where time appears to be stilled, while around them it is accelerated to the point of danger.

The vertiginous implosion of difference which occurs in Tansey's art--in time as well as in landscape-is apparent in his tales about the sexes. In several of his works representations of masculinity and femininity are interchanged, or set adrift. In Judgement of Paris I and Judgement of Paris III it is a woman who judges the "graces" of three men. In the earlier painting a presumably beautiful blond, her back to the viewer, watches three guys scaling a barrier in the midst of an obstacle course. Each man is caught awkwardly straddling the top of the wall--they perform the spectacle of their castration for the blond woman whose face is not visible, but whose stance communicates youthful eagerness. Anxiety about masculine performance is also at the heart of Judgement of Paris III, in which an elegantly dressed woman seated at a nightclub table, with cigarette in hand, chooses between three male types offering her a light: one (the one she "belongs" with, perhaps) offers her his lighter, another a torch and the third a flashlight. Three phalluses/men are presented for her to take-to activate her own fetish, the cigarette. At first glance these two paintings appear as reruns of film motifs-the happy demonstration of virility and the act of gallantry-but both assert an anxiety which lies beneath the ideologically crafted surface of the heroic male.

Although the image of the fumbling man under the gaze of a self-possessed woman reappears in Tansey's work in paintings like Key, an allegory of reentry into the Garden of Eden, the

sexually vulnerable man is replaced in other paintings by the heroic - soldier/artist. Several of Tansey's works have literalized the military connotations of avant -garde rhetoric. In The Triumph of the New York School, a delegation of Parisians headed Andre Breton signs a treaty with American Abstract Expressionists: Clement Greenberg is at the fore, in a pose of good humored but cocky humility. As in so many of Tansey's paintings, an immediate reading-the literal send-up of Irving Sandler's Triumph of American Painting-yields itself to more subtle interpretation. The French are clothed in uniforms from World War I. but the Americans wear "casual" dress dating from the conflict in the Second World War. The treaty is signed in a temporal warp in which a clash of dress codes demonstrates a situation of ideological difference. Tansey shows us two groups of artists in the process of imagining themselves: underlying the visualization of detente is a gulf of cultural difference. As in the Chess Game, where Duchamp's passion for chess-a game which abstracts war-is elided with the signs of actual fighting. Tansey suggests that cultural conflict is protean: it happens symbolically on one front, and literally on another. He constructs a space, a landscape, in which the symbolic and the real coexist naturally: a space reminiscent of the spectacularly unreal milieu of contemporary politics.

But Tansey's apparent "protest" against the militaristic maneuverings of the avant-garde is contradicted by the evident pleasure which he takes in inhabiting the role of the soldier. The End of Painting, painted on a portable movie screen instead of a canvas, shows a cowboy, legs planted firmly apart, pelvis thrust forward, shooting his own image in a mirror. Tansey's allegorical presentation of the fear that modern art would destroy itself through its indulgent self- referentiality is accomplished through the cowboy/painter's enormous narcissistic pleasure -indeed, his masturbatory ecstasy. The critique of modernism here is filled with the self-congratulatory pleasure of modernism's initiates-and the knowledge that the death it deliciously fears, like the "death" that comes with orgasm, is only temporary.

Tansey seems obsessed with illustrating the follies of late modernism. His paintings are rich in art-historical incident, and their dramatic action allegorically takes 20th-century painting to task. But modernism is a subset, or a representation, of all of modernity. In Tansey's paintings modern art serves as an arena for the visualization of the invisible mechanics of ideology. His

landscapes provide the naturalistic settings for a battle of signs: images of war, of gender, of civilized behavior or of forbidden desires are combined like an elaborately hybrid film noir. Tan sey's work makes violent contradictions appear natural, while leaving clues to their impossibility. Starting with the tone of the deadpan, or the one-line joke, he has devised a new kind of realism, within which the seams of apparently seamless repre sentation are strained: a kind of painting where the difficult questions of cultural and sexual difference can be reconstructed. - David Joselit