Harry Gamboa Jr., Willie Herron, Gronk, Patssi Valdez & prijatelji bili su članovi kolektiva ASCO [mučnina] koji je u Los Angelesu '70-ih radio murale, lažne filmove i priređivao barokne hepeninge. Pioniri chicano kulture zanimljivi su i danas.

Harry Gamboa Jr., Willie Herron, Gronk, Patssi Valdez & friends— they did great work then—they didn’t go away.

They painted cracks on the sidewalk and the walls broke open; their murals walked out down Whittier Blvd.

They’re doing it still. Nothing stopped ‘em. This is live!

http://www.harrygamboajr.com/

There’s a tribute to Asco coming to UCLA’s Fowler gallery in 2011, check it out. They could get more real serious reckoning & review.

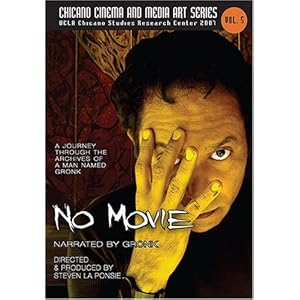

No Movie: A Journey Through the Archives of A Man Named Gronk (Vol. 5)

http://www.patssivaldez.com/

I wrote an introduction to Willie Herron’s exhibit at Galeria Tropico de Nopal a couple years ago. Maybe I can find it and post it here. Willie’s work especially meant a lot to me when we were in high school. We went to Wilson High in El Sereno, and he was already an artist. I saw pieces of one his murals leaning against the wall in Mrs. Gaitzsch, the German art teacher’s room—I recognized it from the neighborhood—we both grew up in City Terrace. Check out his “Wall That Cracked Open” behind Plaza Market in City Terrace Drive; it’s maybe the best mural in the city, or in the state. He demonstrated that you could be an artist in the community. You might be able to survive, actually live positively and contribute positively to the community through art. Against the war in Vietnam, and the wars at home in the neighborhood, you might survive (that in itself came as a surprise) and make an actual contribution to helping people live. Willie, Gronk, Harry, Patssi and the other artists who came and went through Asco have been doing that their whole lives.

Go there some cool evening, Estrada Courts housing project, 3221 East Olympic Blvd., East L.A., with the parents of a girl screaming at some older guy to get away from her or they’ll kill him at the fenceline—it’ll be a trip.

Here’s the intro to the Willie Herron show at Tropico de Nopal:

Visionary Original: Willie Herron

Our childhood was punctuated by assassinations. When president JFK was assassinated, the school played the announcement on the public address system and my teacher cried. When Malcolm X was assassinated, newspapers implied he got what was coming. When Martin Luther King was assassinated, there were riots in cities across America. When Robert F. Kennedy (who had marched with Cesar Chavez) was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire, some Chicanos felt it like yet another body blow of death in the same Catholic family. The Vietnam War went on and on and they announced the tallies of young American dead (not the Vietnamese) on TV every week. Students were killed in campus protests and protestors at the Chicano Moratorium Against the war, as well as Ruben Salazar, reporting for the L.A. Times.. In 1970 my father was shot at work in Watts by a black kid who used a high-powered rifle to shoot at everyone on the street. My dad spent a year in a body cast from his ankles to his chest, and he spent another year convalescing and learning to walk again, but the rest of us did not expect necessarily to survive. It seemed to many of us that it we would not live long if we stood for anything important, anything that mattered, and especially not if we tried to make any difference.

The violence that continually welled up out of the heart of America was without end. Maybe this was the real America—the America that native peoples, informed by genocide, had known all long. AM radio played Dion’s pop tune crooned with sappy melancholy that went,

Anybody here seen my old friend Bobby? Can you tell me where he’s gone? I thought I saw him walkin’ up over the hill… with Abraham, Martin, and John

But that didn’t help. We did not see ourselves strolling over a sunny hill holding hands with MLK, RFK and JFK while Disney cartoon birds chirped overhead, and Porky Pig got ready to stammer, “Th-tha-tha-that’s all folks!”

Life Magazine displayed full color spreads of piles of bodies, 500 unarmed men, women and children machine-gunned on the paths and ditches of My Lai, and television went on reporting the slaughter without comment, as if it was that which was to be expected, and not a single soldier would ever go to prison for murdering a Vietnamese and it was what we expected.

What did we know? There were alternatives. In City Terrace ELA, even in his teens, Willie Herron was articulating a radical vision, a blast of Mexican muralism, pocho defiance, and agit-prop cultural activism. Probably at the time I must have thought that Willie along Chicano movement leaders and secret agents went to some cadre school by boat to Cuba or in the Bolivian jungle to train in identity strategies and existential self-defense. Crawling from the wreck of a family that had crashed and burnt on arrival in ELA shortly before the Watt’s riots of 1965, I was trying to get through my last years of high school, expecting to die or expecting to be sent to Vietnam to kill or to die, and I was heartened and inspired to see—as if born full-grown from his own forehead—Willie Herron’s studio on City Terrace Drive set up in a storefront across from Eva’s Liquors with a matched set of portraits in the window, a 1940/50s couple in zoot suit and coiffed bouffant hairdo, elegantly stylish and poised, confronting the viewer in front of a mysterious black curtain. That was the stark presentation, and to me it said, “No explanations, no apologies. This is it. This is who we are. Deal.”

I recognized Willie’s murals when I saw them going up around ELA too. My parents had been art students—my dad, Anglo World War 2 vet who’d seen service in North Africa and returned to study painting with Clifford Still, Mark Rothko, Richard Diebenkorn, a Beat generation Buddhist who met my mom, a Nisei who’d been interned during the war at Poston, Arizona—but in the face of our family breakup on one hand and a community and nation in crisis on the other, the drunken Buddhism of years on the road and the abstract expressionism of paintings discarded all the way from Oakhurst to San Francisco to Southern California did not seem to provide either terms for personal survival or family self-defense in the times we were faced with. Maybe those artistic notions had worked in the fifties, before all those bottles of booze. Maybe not any more though, and I could see in every facet and detail of Willie Herron’s work, however, here was an articulated political aesthetic that integrated the issues of community, artist, and culture. The roles of these terms were clearly worked out in the imagery, technique, location and message itself. This is an artist who makes work which exists—and lives—in our world, on its street corners, in alleys, in storefronts, on the avenues. Here was an artist who was working out terms on which we too might yet survive in this place. I was impressed and instructed at once by his work.

Willie’s murals—impressing me even at midnight visiting a girlfriend in Ramona Gardens, crossing White Fence territory to try to see her, strolling through the blockhouse projects to inspect murals on the end of each row where it met the street—Willie’s bravura draughtsmanship was recognizable. Also emblazoned in a trajectory of historic faces across the front of Farmacia Hidalgo on my endless peregrinations and wanderings up and down City Terrace Drive—these were my first intimations of a whole tradition of Siqueiros or Rivera murals in public locations like the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City or the Orozco ‘Man on Fire’ in the orphanage in Guadalajara, which I hadn’t even heard of, let alone seen for myself. Late one afternoon, in one of those last years of high school in one of the art classrooms of a certain Mrs Gaitzsch, the art teacher, I came across, stored on the floor along the wall a mural that had been painted on diagonal, maybe triangular, panels, and in the darkened empty classroom I recognized Willie Herron’s imagery. It was dismantled, out of order, random, but struck by it, I walked back and forth in front of it. It was unmistakably Willie Herron. Instructive, because real.

You could see it in the street, in the alley behind Plaza Market (his legendary “Wall That Cracked Open,” that visionary, almost hallucinatory response to the near fatal stabbing of his brother Johnny, who’d been my classmate at City Terrace Elementary) or the serpentine kitty corner to the public library, or—another legendary piece—a newsreel of a mural (as if directed by Fellini) depicting the outrageous violence of the sheriffs’ attack on the Chicano Moratorium in Cinemascope black and white in Estrada Courts. Years later when friends visited from out of town, these were among the only landmarks I would take them to see. Willie Herron’s art was the clearest, most intelligent response—and a way forward—out of years whose savagery, then, was not yet over.

And we did not know if we would survive.

Some of us will. And, meantime, Willie Herron’s art always did, and does, indicate a way forward.

- Sesshu Foster

Chicano Pioneers

LATE one December night in 1972, three members of an art collective here clambered out of a battered green Volkswagen bug and spray-painted their names — “Herrón, Gamboa, Gronkie” — on a footbridge of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, appropriating the entire museum as their own work of art simply by signing it.

The next morning Harry Gamboa Jr. returned with the fourth member of the

group, Patssi Valdez, and immortalized the act with a glam shot of her

posing in tight pants and a red top near the signatures, looking away

coolly and seductively like Anna Karina in a Godard movie.

The stunt by the collective known as Asco exhibited all the hallmarks of

the group’s outrageous style: angry, illicit, deftly and economically

conceptual, and shot through with the high camp of Hollywood, whose sign

they could see in the distance from the streets of East Los Angeles.

The act was also pretty much noticed by no one except the four members

themselves, who were always their own best audience. The paint was

whitewashed before day’s end; the Los Angeles art world went on its way,

paying little attention to a group of artists whose street performances

and other unclassifiable productions were as compelling as practically

anything bubbling up out of the urban dereliction of SoHo or other parts

of Los Angeles during those years.

Almost four decades later, the same museum the collective defaced

because its doors weren’t open to artists of their kind —

Mexican-American, working class and poor, highly irreverent and

politicized — is not just finally welcoming them inside but rolling out a

red carpet for the occasion. “Asco: Elite of the Obscure, a

Retrospective, 1972-1987,” the first survey of the group’s work, opens

Sept. 4 as one of the Los Angeles County Museum’s main offerings for the

sprawling Pacific Standard Time event, more than 60 collaborative shows

opening throughout Southern California in the late summer and fall to

tell the story of postwar Los Angeles art.

The Asco exhibition — organized with the Williams College Museum of Art

in Williamstown, Mass. — has been almost a decade in the making. And its

goal is nothing less than to rewrite part of that story and the broader

history of urban art in the 1970s to give the collective its rightful

place among the pioneers of its era. “It’s a show that’s phenomenally

overdue,” said C. Ondine Chavoya, an associate professor of art at

Williams College and one of the exhibition’s curators. “I felt it was

overdue at the very moment I learned about Asco’s work many years ago.

And now coming as it does as part of Pacific Standard Time means that

it’s not going to be isolated or singular. It’s going to tie them in,

finally, to a much larger history.”

The show is only one of several Pacific Standard Time shows delving into

the history of Chicano art in the 1960s and ’70s, whose attitude and

look seeped into mainstream art in ways only now being recognized. But

the story of Asco lies even deeper, one of a subculture within a

subculture, a group of artists fueled not just by their marginal

existence within their city and country but by their alienation from the

Chicano art movement as well.

The members were, as Mr. Gamboa has described it, “self-imposed exiles”

who felt the best way to exercise artistic freedom and express

solidarity with the Mexican-American cause was, paradoxically, to run

screaming from most Mexican-American art at the time, or at least from

its political strictures and the stereotypes imposed on it by mainstream

culture.

Asco’s method was a kind of bombastic excess and elegant elusiveness

that would have made Tristan Tzara proud, not to mention Cantinflas and

Liberace. The Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight wrote that

the group “brought Zurich Dada of the late-1910s to 1970s Los Angeles.”

But it was a distinctly Chicano brand of Dada, by way of David Bowie

and Frank Zappa, drag and Pachuco culture, telenovelas and oddball UHF

television stations, and New Wave and silent movies.

“Part of the art was just the idea that you would try to draw attention

to yourself the way we did at a time when everyone around us was

existing in despair,” Mr. Gamboa said in a recent interview, speaking of

the guerrilla escapades of the group, whose members went their separate

ways in 1987 and now barely speak to one another as the spotlight has

reunited them.

In a 1997 interview with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, one

of the group’s founders, the artist who calls himself Gronk (though at

times also Groak and Grunk) described the collective as “just a rumor to

a lot of people for the longest time” and “sort of thought of as drug

addicts, perverts.”

“All kinds of names were hurled at us by other Chicano artists,” he said.

The collective’s chosen name, Asco, set the outré tone — it means

disgust or nausea in Spanish and also evokes a sinister corporation or a

mockery of the acronyms of the social-service organizations then

proliferating in poor neighborhoods as a legacy of President Lyndon B.

Johnson’s Great Society. But the foursome’s unpredictable street theater

and prodigious image-making beginning in the early ’70s — fake

publicity shots and film stills, Super-8 movies, mail-art fliers — made

clear that they were not simply trying to express their disgust with

racism, police harassment and the Vietnam War but also using revulsion

as a raw material and spreading a fair amount of it around.

Their first performance, “Stations of the Cross,” staged during the

Christmas holidays in 1972 before the group had gelled or chosen its

name, involved Mr. Gamboa, Gronk and Willie Herrón, another of the

group’s founders, mocking both Mexican Catholic holiday traditions and

the look of classic Mexican murals. The three dressed up as macabre

pilgrims and unsettled shoppers along Whittier Boulevard, East Los

Angeles’s central artery, trudging along with a huge cross made from

cardboard, which they eventually dumped in front of a Marine Corps

recruiting station; then they ran away.

Several years before Cindy Sherman started photographing herself as the

protagonist in nonexistent movies to strip-mine the mechanisms of

America’s image-making, Asco began an extensive body of work called “No

Movies,” in which the members dressed up and photographed wildly

cinematic scenes — one of the funniest and most memorable was called

“The Gores,” a sort of Mansonesque horror movie inspired by pop singer

Leslie Gore — late at night on the Los Angeles streets. The images from

these never-to-be movies were then mailed out widely like publicity

materials, a project that, as the film scholar David E. James notes in

the show’s catalog, articulated deeply “both the affection and the

anger, the desire and the hatred” the collective’s members had for the

movies, in which people who looked like them were almost never seen.

Asco’s founders, now all in their late 50s, met at Garfield High School

in East Los Angeles, which also produced the members of the band Los

Lobos and became known later for the work of the teacher Jaime

Escalante, of “Stand and Deliver” fame.

While Gronk was Asco’s only gay member, an androgynous sensibility

pervaded the group — in its photographs, its performances and

particularly its look, with lots of shaved eyebrows and Theda Bara

makeup.

In many of their no-budget, experimental antics, the group’s chief worry

was almost never the conventional one for artists — Will anyone pay

attention to us? — but whether the attention they got would get them

arrested or attacked or worse.

“I always felt like a bullfighter in many ways,” Mr. Gamboa said in a

recent interview over lunch with Mr. Herrón at the Los Angeles County

Museum, only a hundred yards from the spot where they once spray-painted

their names. “The art was to walk away unscathed but to have touched

the danger.”

And the danger was often very real. In one of the group’s pieces, “Decoy

Gang War Victim,” from 1974, Asco members went at night to

neighborhoods marred by gang violence and created fake crime scenes, in

which Gronk would play a young corpse on the pavement, surrounded by

police flares. The scene would be photographed and the pictures would be

sent to newspapers and television stations, as a way to sow confusion

both in the news media — which Asco saw as inciting and perpetuating

gang violence — and maybe even among the gangs themselves, to prevent

more violence.

The performance recalls one from 1972 by a fellow Angeleno and recent

M.F.A. graduate, Chris Burden, “Deadman,” in which he placed himself

under a tarp surrounded by flares on a busy city street, where cars

swerved to avoid him.

Asco’s ideas sprang less from the kind of Conceptual explorations of

performance and body art then pouring out of graduate art programs and

more from their experience on the streets transformed by media-saturated

urban savvy, what Gronk called an “aesthetics of poverty.”

But the methods and results were often strikingly similar to those of more established artists.

“What we’ve been up against is the idea, I think, that these are just

regional artists or that they mattered only within the context of a

certain time in L.A.,” said Rita Gonzalez, the show’s curator along with

Mr. Chavoya. “They never achieved the market success of a lot of their

peers or the esteem within academia.”

Part of this was by design, of course, growing out of a deep ambivalence

about the establishment’s embrace. The group’s founders have since gone

on to individual careers — Ms. Valdez is a painter; Mr. Gamboa teaches

at the California Institute of the Arts and remains an active artist;

Mr. Herrón is a painter and founder of the punk band Los Illegals; Gronk

is a successful artist and stage designer, collaborating most recently

with Peter Sellars.

But all, to varying degrees, have sought success only on their own

terms. As Mr. Gamboa once told a Smithsonian interviewer, with wonderful

Seinfeldian skepticism: “I look at that carrot and it looks a little

spoiled to me. I’m not exactly allergic to carrots, but the way it’s

dangling — it just — it doesn’t look right. It should be at least on a

plate.”

Even now that the Los Angeles County Museum is delivering the carrot on

what is arguably a pretty nice plate — a show of photographs, films and

artworks that will take up half a floor of the Broad Contemporary wing,

accompanied by a hefty catalog — not all are so sure they’re happy. “The

big surprise of the show is that we’re all going to be in it, too,

stuffed,” said Mr. Herrón, who wears a safety-pin earring and a pair of

jet-black shades that never leave his face.

Like many struggling young bands that basically grew up together, Asco —

which expanded in the 1980s to include a large number of new members

and collaborators — eventually imploded, the result of longstanding

rivalries and grudges among its founders, which linger today.

“We all defied Newton,” Mr. Gamboa said by way of explanation. “For

every action, there was a completely disproportionate reaction.”

But the end result was not exactly a surprise for a group that usually

operated at white-hot intensity, he said, adding that he had no idea

whether the retrospective would ultimately result in the recognition he

and his former collaborators deserved or whether, true to Asco’s nature,

the collective would always be more a legend than a fact.

“Who knows?” he said. “That’s the way L.A. is, too. It’s a desert with

mirages. A thing happens and then, poof, it’s gone.”

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar