Ako ste svjesni relativnosti/konstruiranosti svega ali zbog toga ipak ne mislite da ništa nije "univerzalno" i ne želite biti netko tko ni u što ne "vjeruje", ako težite novoj velikoj meta-naraciji svijeta iako unaprijed znate da će i ona biti problematična, ovaj izam je za vas (zapravo za sve nas, jer nitko nije potpuno dosljedan u svojoj pretjeranoj "osviještenosti"). Za stalno osciliranje između modernizma i postmodernizma, nade i sumnje, iskrenosti i ironije, informiranosti i naivnosti sad postoji naziv - metamodernizam.

Metamodernism is a term employed to situate and explain recent developments across current affairs, critical theory, philosophy, architecture, art, cinema, music, and literature which are emerging from and reacting to postmodernism.

The term metamodernism was introduced as an intervention in the post-postmodernism debate by the cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in 2010. In their article 'Notes on metamodernism'they assert that the 2000s are characterized by the return of typically modern positions without altogether forfeiting the postmodern mindsets of the 1990s and 1980s. The prefix 'meta' here refers not to some reflective stance or repeated rumination, but to Plato's metaxy, which intends a movement between opposite poles as well as beyond.

Van den Akker and Vermeulen define metamodernism as a continuous oscillation, a constant repositioning between positions and mindsets that are evocative of the modern and of the postmodern but are ultimately suggestive of another sensibility that is neither of them: one that negotiates between a yearning for universal truths on the one hand and an (a)political relativism on the other, between hope and doubt, sincerity and irony, knowingness and naivety, construction and deconstruction. They suggest that the metamodern attitude longs for another future, another metanarrative, whilst acknowledging that future or narrative might not exist, or materialize, or, if it does materialize, is inherently problematic.

As examples in current affairs Vermeulen and van den Akker cite the multiple responses (such as an 'informed naivety', 'pragmatic idealism' and 'moderate fanaticism') to climate change, the financial crisis and geopolitical instability. In the arts, they cite the return of transcendentalism, Romanticism, hope, sincerity, affect, narrativity, and the sublime. Artists and cultural practices they consider metamodern include the architecture of BIG and Herzog and de Meuron, the cinema of Michel Gondry, Spike Jonze, Gus van Sant and Wes Anderson, musicians such as CocoRosie, Antony and the Johnsons, Georges Lentz and Devendra Banhart, the artworks of Peter Doig, Olafur Eliasson, Ragnar Kjartansson, Šejla Kamerić and Paula Doepfner, and the writings of Haruki Murakami, Roberto Bolano, David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Franzen.

The artist Luke Turner published a metamodernist manifesto in 2011 calling for an end to "the inertia resulting from a century of modernist ideological naivety and the cynical insincerity of its antonymous bastard child", and instead proposing "a pragmatic romanticism unhindered by ideological anchorage."

In January 2011, the German newspapers Die Zeit and Der Tagesspiegel proclaimed metamodernism as the new dominant paradigm in the arts.

In September 2010, Galerie Tanja Wagner curated the first exhibition explicitly linked to metamodernism, including the artists Mariechen Danz, Routes Award winner Sejla Kameric, Issa Sant, Angelika Trojnarski and Paula Doepfner. There have since been three exhibitions on metamodernism: No More Modern at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, Notes on Metamodernism at the Moscow Biennial, and Discussing Metamodernism at Galerie Tanja Wagner, Berlin. Artists included in these shows were Olafur Eliasson, Mona Hatoum, Monica Bonvicini, Ragnar Kjartansson, Sejla Kameric, Andy Holden, David Thorpe, Luke Turner, Kris Lemsalu, Guido van der Werve, Pilvi Takala, Ulf Aminde, and Mariechen Danz.

In June 2010, van den Akker and Vermeulen initiated the webzine Notes on Metamodernism. The webzine brings together a new generation of scholars and critics from a variety of nationalities and disciplines working on tendencies in philosophy, politics and the arts that can no longer be described in terms of postmodernism but need to be conceived of by way of another vernacular. Since the webzine's inception, it has featured the work of amongst others Niels van Poecke (Erasmus University Rotterdam), Reina Marie Loader (Exeter University), Leonhard Herrman (University of Leipzig), Nadine Feßler (University of Munich), James MacDowell (University of Warwick), Hanka van der Voet (Modelectoraat ArtEZ), Luke Butcher (Manchester School of Architecture), as well as the New York based critic David Lau.

The term metamodernism was previously adopted by the literary theorist Alexandra Dumitrescu to describe the contemporary paradigm, the poetry of William Blake,[9] the fiction of Arundhati Roy,[10] Michel Tournier, and also by Andre Furlani to describe the work of Guy Davenport. In Brazil, Philadelpho Menezes and Jayro Luna have used the term Metamodernism since 1986. Philadelpho Menezes published the book "A Crise do Passado: Modernidade, Vanguarda, Metamodernidade" (The Crisis of the Past: Modernity, Vanguard, Metamodernity - 1994) and Jayro Luna[12] some papers published in 1986: "Meta Metamoderno nisso aí", "Bibliotecas Metamodernas", "Da Metalinguagem ao Metamoderno", meeting after in the book "Participação e Forma" (Participation and Form - 2001). The Indian spiritual teacher, Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi used the term in her book, Meta Modern Era (1995). -wikipedia

Dictionary

timotheusvermeulen.com/www.metamodernism.com/

The postmodern years of plenty, pastiche and parataxis are over. In fact, if we are to believe the many academics, critics and pundits whose books and essays describe the decline and demise of the postmodern, they have been over for quite a while now. But if these commentators agree the postmodern condition has been abandoned, they appear less in accord as to what to make of the state it has been abandoned for. On this blog, we will seek to outline the contours of this discourse by looking at recent developments in architecture, art, and film. We will discuss practices and works as diverse as the grand buildings of Herzog & de Meuron to the installations of Bas Jan Ader, the collages of David Thorpe, the paintings of Kaye Donachie and the films of Michel Gondry and so forth and so on. The postmodern is over. The metamodern has arrived. But what is it?

The postmodern years of plenty, pastiche, and parataxis are

over. In fact, if we are to believe the many academics, critics, and

pundits whose books and essays describe the decline and demise of the

postmodern, they have been over for quite a while now. But if these

commentators agree the postmodern condition has been abandoned, they

appear less in accord as to what to make of the state it has been

abandoned for. In this essay, we will outline the contours of this

discourse by looking at recent developments in architecture, art, and

film. We will call this discourse, oscillating between a modern

enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, metamodernism. We argue that the

metamodern is most clearly, yet not exclusively, expressed by the

neoromantic turn of late associated with the architecture of Herzog

& de Meuron, the installations of Bas Jan Ader, the collages of

David Thorpe, the paintings of Kaye Donachie, and the films of Michel

Gondry.

Keywords: metamodenism; New Romanticism; structure of feeling; contemporary aesthetics

(Published: 15 November 2010)

Citation: Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Vol. 2, 2010 DOI: 10.3402/jac.v1i0.5677

Keywords: metamodenism; New Romanticism; structure of feeling; contemporary aesthetics

(Published: 15 November 2010)

Citation: Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Vol. 2, 2010 DOI: 10.3402/jac.v1i0.5677

Postmodernism

is over. As global warming, the credit crunch and political

instabilities are rapidly taking us beyond that so prematurely

proclaimed ‘End of History’, the postmodern culture of relativism, irony

and pastiche, too, is superseded by another sensibility. One that

evokes the will to look forward, that invokes the will to hope again.

Postmodernism

is over. As global warming, the credit crunch and political

instabilities are rapidly taking us beyond that so prematurely

proclaimed ‘End of History’, the postmodern culture of relativism, irony

and pastiche, too, is superseded by another sensibility. One that

evokes the will to look forward, that invokes the will to hope again.Metamodernism is the concept used in recent philosophy to describe the period after postmodernism. The prefix ‘meta’ here stands for metaxy (μεταξύ): oscillation. Metamodernism oscillates, swings back and forth, between the global and the local; between concept and material; between postmodern irony and a renewed modern enthusiasm. It yearns for a truth it knows it may never find, it strives for sincerity without lacking humour, it engages precisely by embracing doubt.

Since metamodernism was introduced into the debate by the cultural philosophers Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in the late 2000s, it has been the topic of numerous conferences, symposia and debates. Articles about metamodernism have been published in various journals, magazines and books, among others: The Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Frieze, and MONU. Two books are currently in preparation.

Galerie Tanja Wagner is pleased to present Discussing Metamodernism with works by Ulf Aminde, Yael Bartana, Monica Bonvicini, Mariechen Danz, Annabel Daou, Paula Doepfner, Olafur Eliasson, Mona Hatoum, Andy Holden, Šejla Kamerić, Ragnar Kjartansson, Kris Lemsalu, Issa Sant, David Thorpe and Angelika J. Trojnarski and Luke Turner/Nastja Rönkkö, curated in collaboration with Robin van den Akker and Timotheus Vermeulen.

“Discussing Metamodernism” with Tanja Wagner and Timotheus Vermeulen

In any moment, it’s nearly impossible to locate or isolate shifts, changes in tendencies, whether social, aesthetic, or otherwise—banal critical statement of the year, certainly. But, for Berlin’s (and the art world’s at large) current state of flux, of non-identity and non-identification, perhaps such a naming is needed. For Robin van den Akker, Timotheus Vermeulen, and gallerist Tanja Wagner, that name is Metamodernism.

So, in the exhibiton you are “Discussing Metamodernism,” but what is Metamodernism?

Timotheus Vermeulen: It’s mainly an attempt to continue language for what’s happening. Everyone realizes, I think, that something is happening, all the magazines are realizing it, but people do not really have the (? immaculacy 00.01.30) to speak about it, they don’t know how to name or how to label things that are happening. Like Ragnar Kjartansson, I think, for example, Šejla’s work, which is infused with what we might call postmodernism, but it isn’t postmodern at all, so something was happening, something was emerging from this postmodern sensibility. Damien Hirst, Cindy Sherman and all those people, you know, who now seem to an extent anachronistic almost, so there’s something very odd going on there, and metamodernism was made as an attempt to come to terms with this. And so because Tanja was working with similar sensibilities, we were talking quite quickly about making an exhibition with the artists that we thought would exemplify these discourses but also take them further.

Tanja Wagner: We’ve been talking about trend tendencies for a long time and what our generation is about, what we feel is important, or what we want to get across. I had the feeling when I was looking for artists for my program, that artists really want to have a dialogue again. They want to engage again, but not in a dry conceptual way. These artists want affect again, they want to talk about love, which I thought was almost not possible, to talk about love, and in a very serious way. We don’t know yet in which direction this is going to go, or is there even one answer, or does there have to be one answer, but still we’re trying to take sides here, so it’s not just open, and you can do whatever, you know.

What do you both see as the turning point for Metamodernism, or is there a turning point that can you peg down?

TV: I think it emerges partly from the variety of crises that were in: the ecological crisis and the geopolitical crises, and the economical crisis. People from my generation, we always thought that we’d have better lives than our parents, and now we are realizing that it’s possible that we won’t. So it’s both a reaction to all sorts of things happening around us in the world and to the generation above us, a generation of baby boomers and post baby boomers for whom life was great and easy, and they could do whatever they wanted, which is a simplification of course, but I think there was this sensibility, and I think it was this generation saying, “All right parents, that’s okay, but we need to do something, we need to find a way in order to get ahead, to get better, to do something new.” It is very much a generation thing. I think it’s fair to say that somewhere in the early 2000’s, things were changing.

So, is part of the movement Metamodernism to reclaim the soul or autonomy of art rather than it’s object life?

TV: Yeah, I think so. Postmosdernism is engrained in our souls. We don’t have a soul, but it’s engrained in a fragmentary thing that we might call a soul. There’s so much irony that we would always laugh at everything we do so that we would say “I love you”, but we would laugh about it; we would say “I am a subject, I am a real person”, and we would laugh about it. Postmodernism is completely engrained in us, yet it doesn’t mean that we cannot try to reclaim or claim anew some territory, some space for art as something that might get us somewhere else. So they’re trying to claim a new soul for the arts whilst knowing that to do that is almost impossible. I think what we see now is a movement between these modernist ideals of unity and utopia and the postmodern knowledge that these things are impossible, without really giving in to either one. It’s a constant tension and a “trying in spite of”. We need to try, although we know it’s very likely that we’ll fail. Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst would just say well let’s fail, you know they’re actually going to celebrate failure or celebrate the state that we’re in now or alternatively completely deconstruct that state. And these artists are deconstructing the state that we’re in but at the same time constructing a new thing, which then of course is also impossible.

In some sense is it a negation or temporary suspension of ironic modes of communication?

TV: I think irony is still very much there; I think it’s impossible for us to not be ironic. But what happens with these artists is that for a moment, they put on this sort of sincerity or earnestness, and it’s just suspending irony, they know it’s there, but for a moment they say “I love you”, or for a moment they will say “this is real”. Furthermore, I think we shouldn’t go without irony, because it’s so important as a sort of holding in check keeping us from becoming modern fanatics.

TW: Let’s say two years ago, when you saw the artists and the statements there, they would decide maybe that they would just be funny or ironic, or that they would try to make very clean, cold, conceptual pieces, that were very earnest, Now they’re trying to mix both, to enjoy the art works again and laugh.

So there’s kind of a performative ambiguity present?

TV: Yes, I think so very much, I think that’s really what most of this work is about, to do something although you can’t do it or you shouldn’t do it. You’re constantly putting on a performance to stay sincere or honest as long as you can, although you’re constantly aware that you can’t really. It’s a constant struggle.

How did you go about picking the artists for the show?

TW: I mean, we could have had 150 or just three. I feel very close to the concept, so I’m showing the artists of the gallery, and then additionally eight or nine more positions, which we chose these artists because we felt very close with them, and also because they were very happy to engage in this show.

TV: But it’s difficult, because I mean we came up with the concept of metamodernism because we saw it everywhere, in all the galleries and young galleries and fairs we saw art that was suddenly something different but not grouped, I think what Tanja has done is that she’s really grouped some of these artists that we would find metamodern together, but we saw it emerging everywhere, I’m sure you also.

And nobody knows what to call it but you feel it. It’s a felt, more affective stance.

TV: Exactly. And we came up with the concept of metamodernism and we know it’s a ridiculously grand gesture, especially in postmodern times I think many people think, “Ahh well, what arrogant pricks who think that they can come up with something else.” But I think it’s necessary that we all do this and that we try to make these enormous gestures again of saying we’re seeing this, we don’t have a word for it, try to map out what’s happening. It’s very much like an open source project, where we can all chip in and try to find what is it that’s going on. As you say, everyone feels it, people are feeling that something is changing and they’re always too late to get a hold of it.

How does the theoretical aspect interface with practice? Do you see your job as purely picking up ideas out of what you’re seeing, or is it also an authoritarian stance pushing on artists and their praxes?

TV: I don’t know how it is for Tanja, but for Robin and me it was very much a description of what we saw happening. One of our contributors in the show was Luke Turner; he made a manifesto of the Metamodern disposition. But for us it’s not a manifesto; it’s not a blueprint for how to achieve things. We just want to describe what we think is going on and try to categorize or to get a hold of it or to try to understand what’s going on, but for us it’s a description rather than a blueprint.

TW: For me it actually all started for me when I said that I’ll open my own gallery, showing what am I personally interested in, what I want to talk about, what is different now. We are the new generation of gallerists. We are showing new artists, young artists. I really wanted to work with artists who really engaged again and who told a story. I wanted to open up a dialogue. I wanted to not have a clean space in a very 90s sense, white cube kind of thing.

It’s an interesting thing also for a gallery to do. Is that something that you feel is important for the galleries now, for the commercial market to engage in a deeper discussion as well?

TW: That was my personal idea, but why should it only be the artist that asks questions? Everyone could do this: what do you want to get across working in a bank? I don’t think it’s limited to creative people to get something across. It’s not at all at odds to have a very stimulating program and still be very commercially active. Fortuantely so far this hasn’t proven me wrong. Maybe because of the times collectors are also interested in showing or building up a collection with interested works.

TV: We just really wanted to work with Tanja, actually. We got some offers from other institutions and galleries, but we really wanted to work with someone young and someone we felt was on sort of the same wavelength. We really wanted someone from our generation to do it. It’s not saying that we are discriminating against generations from the past, but we really felt that this should be someone who goes through the same moods and swings as we are going through at this moment.- blogs.artinfo.com/

MeMo: Hope & Change After Cultural Suicide?

Metamodernism

is a movement emanating from the Radboud University of Nijmegen in the

Netherlands, and is emerging from and as a reaction to pOmo. The term

Metamodernism was introduced as an intervention in the post-Postmodernism debate in 2010 by cultural theorists, Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker.

Whereas pOmo is

denying objective reality, truth and the possibility of human knowledge

with a view to cultural destruction through philosophical

desintegration, Memo is no longer convinced of these absolute tenets.

Or, at least, Memos are fed up with the void and the cynicism that comes

with the Reification of Zero and perpetual tethering on the brink of the existential abyss. How long can a human being live without hope or purpose?

Memo isn't sure either of a goal to human existence, but in order to get past the destructive 'irony' rooted in egalitarian Nihilism Memo propose to start moving away from the cliff, pending the discovery of a Sense of Life.

Whence and how salvation is about to come from is obscure for the

moment. But while we wait for it to emerge, the feeling is clothed in

nostalgic Romantic Realism.

Meta stands for Plato's metaxis: in between. Since Memo, like pOmo denies fixed constants, it is part of the famility tree of Pragmatism. Pluralism

is an undefined position between modernist universalism and pOmo

multiculturalism; Memo on the other hand is an unfixed position,

oscillating between the absolutism of modernism and the relativism of

pOmo. Where precisely the modernist constant lurks, it unclear for the

moment.

The Metamodern attitude longs for another future, a new grand narrative

(subjective group reality), but acknowledges that narrative or even

truth might not exist, or materialize, or, if it does, is inherently

problematic because there is no fundamental break with the fallacies of

pOmo (check the chart @bottom).

While pOmo suffers from the flaw in its absolute claim that reality is

subjective and man made, Memo may actually be worse in that it

acknowledges it is not even sure of that much. But Memo is a step

forward in that it is intellectually more honest, is of good will

towards life and a benevolent universe, and therefore abandons pOmo's scorched earth mentality. But the good news may be offset by... Luke Turner's Manifesto (2011):

1. The unfixed position is the natural state of the world.

2. We must break free from a century of "inertia" between modernist

naive honesty and pomo cynical dishonesty, which is a strange way to

describe an all out war of ideas in which the end justifies the means

(check the comments).

3. We are committed to progress by means of something that looks like the Hegel dialectic but

isn't - a colossal electric machine, propelling the world into action.

Check the comments for the Memo dialectic! It skips the synthesis part.

4. We are subject to the laws of nature. We must adhere to that, but we

can evade them with impunity because life is richer if we act as if

there were no such limitations to reality.

5. Everything is inevitably going to pieces. The stress that ensues is the subject of artistic creation.

6. The present is a symptom of the here and now and what has come and

gone. New technology enables multiple perspectives and experiences,

enabling historical research along grand narratives.

7. Truth may or may not exist. Science strives for it, artists may find

it. All information may lead to knowledge, whether the source is

experience or proverbial, however faulty its magical realism. Error

leads to sense [sic]. Epistemologically Memo is completely on the fence: it is entirely agnostic in that department.

8. Memo propose a pragmatic, unprincipled modernism (Romanticism). Memo

is an unfixed state of mind between, beyond and in pursuit of a number

of different and fragmented world views. Check Luke's comments: while

oscillating, these are not undefined.

Conclusion: This baby is ninety percent pOmo. Memo differs in that it wants to rid itself of the cynicism rooted in Nihilism and accepts there is something like an external reality; but it is still subjective and human knowledge is as illusive as ever. But like the Skeptics, Memo feels sadness over the loss. It certainly doesn't celebrate ignorance, as pOmo does.

pOmo on the DIM scale is a firm D for Disintegration; Memo for the time being is probably a M2 pending some clarification on metaphysics and epistemology.

While research is ongoing and Memo is trying to establish where to go next, the prediction is safe that pOmo is now on the retreat, selfdefeating as suicide by definition is. We are going somewhere, but we have no idea of the next destination.

"Would you be willing and able to act, daily and consistently, on the belief that reality is an illusion?" ~Ayn Rand

Conclusion: This baby is ninety percent pOmo. Memo differs in that it wants to rid itself of the cynicism rooted in Nihilism and accepts there is something like an external reality; but it is still subjective and human knowledge is as illusive as ever. But like the Skeptics, Memo feels sadness over the loss. It certainly doesn't celebrate ignorance, as pOmo does.

pOmo on the DIM scale is a firm D for Disintegration; Memo for the time being is probably a M2 pending some clarification on metaphysics and epistemology.

While research is ongoing and Memo is trying to establish where to go next, the prediction is safe that pOmo is now on the retreat, selfdefeating as suicide by definition is. We are going somewhere, but we have no idea of the next destination.

"Would you be willing and able to act, daily and consistently, on the belief that reality is an illusion?" ~Ayn Rand

4 comments:

- Luke Turner1/20/2013 6:58 PMHi Cassandra, I don't believe there's any mention of synthesis or balance in my text. Nor is there a definitive assertion of the existence of truth, as you seem to make out. The paraphrasing here is quite misleading, as it omits any sense of the essential metamodern yearning, born of an informed naivety. Nonetheless, I'm happy to see your recognition of the re-emergence of hope!Reply

- Tx for setting the record straight, Luke. As critics we really need to get the hang of this.Reply

I realize you used the word inertia instead of balance. Balance is my own personal experience of the standoff between modernism and postmodernism. I think inertia is far to neutral a word. Lots of things happened.

The mechanism you describe in point 3. looks like the Hegel dialectic, the essence of which is veering from thesis to antithesis, resulting in a form of synthesis. Perhaps you mean something different altogether. If so, I'm looking forward to your clarification.

With regard to truth, here you have me. I´m reading contradictory premises from various texts. On the one hand there´s your point 7 `artists might assume a quest for truth` assumes that it exists. On the other hand I am not surprised to find some remnants of truthphobia in your comment.

I´d like you also to have a look at the chart. I have for the time being categorized metaphysics as supernaturalism. However, informed naivety seems to refer to a form of Rationalism, probably Skepticism. Perhaps you can set the record straight here as well. Tx. - Come to think of it, balance is also the wrong word, considering the philosophical battle has been moral in nature, a war upon life and death! There has never been a stand off. Pomo was designed to win the war by al means at its disposal. I used the word balance to convey the fact that the fight isn't over. Pomo is going to lose and Memo is the first sign of that defeat.Reply

- Luke Turner1/21/2013 1:30 PMThe word inertia is used here to describe the feeling of immobility (cultural, political, etc.) in the aftermath of postmodernism towards the end of the last century. I don't see this as indicative of balance. The mechanism described in point 3 is one that seeks to empower movement in itself, rather than lead to any synthesis ("propelling the world into action").

On the question of truth, a quest for something certainly does not guarantee its existence. Though I don't view this as truth-phobia either. In addition, the "pursuit of a plurality of disparate and fragmentary horizons" does not imply that each is necessarily considered "undefined" (as you put it) by the individual.

As for the chart, I think an attempt to categorise metamodernism as either one thing or the other in this regard is somewhat misguided, as oscillation is its distinguishing trait. Rationalism/fideism, pragmatism/romanticism, cynicism/sincerity, etc. I hope this helps.

Luke Turner, Metamodernist Manifesto

1.

We recognise oscillation to be the natural order of the world.

2.

We must liberate ourselves from the inertia resulting from a

century of modernist ideological naivety and the cynical insincerity of

its antonymous bastard child.

3.

Movement shall henceforth be enabled by way of an oscillation

between positions, with diametrically opposed ideas operating like the

pulsating polarities of a colossal electric machine, propelling the

world into action.

4.

We acknowledge the limitations inherent to all movement and

experience, and the futility of any attempt to transcend the boundaries

set forth therein. The essential incompleteness of a system should

necessitate an adherence, not in order to achieve a given end or be

slaves to its course, but rather perchance to glimpse by proxy some

hidden exteriority. Existence is enriched if we set about our task as if those limits might be exceeded, for such action unfolds the world.

5.

All things are caught up within the irrevocable slide towards a

state of maximum entropic dissemblance. Artistic creation is contingent

upon the origination or revelation of difference therein. Affect at its

zenith is the unmediated experience of difference in itself. It must be art’s role to explore the promise of its own paradoxical ambition by coaxing excess towards presence.

6.

The present is a symptom of the twin birth of immediacy and

obsolescence. The new technology enables the simultaneous experience and

enactment of events from a multiplicity of positions. Far from

signalling its demise, these emergent networks facilitate the

democratisation of history, illuminating the forking paths along which

its grand narratives may navigate the here and now.

7.

Just as science strives for poetic elegance, artists might

assume a quest for truth. All information is grounds for knowledge,

whether empirical or aphoristic, no matter its truth-value. We should

embrace the scientific-poetic synthesis and informed naivety of a

magical realism. Error breeds sense.

8.

We propose a pragmatic romanticism unhindered by ideological

anchorage. Thus, metamodernism shall be defined as the mercurial

condition that lies between, beyond and in pursuit of a plurality of disparate and fragmentary horizons. We must go forth and oscillate!

The ecosystem is severely disrupted, the financial system is increasingly uncontrollable, and the geopolitical structure has recently begun to appear as unstable as

it has always been uneven. This triple crisis infuses doubt and

inspires reflection about our basic assumptions, as much as inflaming

cultural debates and provoking dogmatic entrenchments. History, it seems, is moving rapidly beyond its all too hastily proclaimed end.

Since the turn of the millennium,

moreover, the democratization of digital technologies, techniques and

tools has caused a shift from a postmodern media logic characterized by

television screen and spectacle, cyberspace and simulacrum towards a

metamodern media logic of creative amateurs, social networks and

locative media – what the cultural theorist Kazys Varnelis calls network culture. [1]

Meanwhile, architects and artists

increasingly abandon the aesthetic precepts of deconstruction,

parataxis, and pastiche in favor of aesth-ethical notions of reconstruction, myth, and metaxis. These

artistic expressions move beyond the worn out sensibilities and empty

practices of the postmodernists not by radically parting with their

attitudes and techniques but by incorporating and redirecting them. In politics as in culture as elsewhere, a sensibility is emerging from and surpassing of postmodernism; as a non dialectical Aufhebung that negates the postmodern while retaining some of its traits.

What we are witnessing is the emergence of a new cultural dominant – metamodernism.

We understand metamodernism first and

foremost as a structure of feeling, which can be defined, after Raymond

Williams, as “a particular quality of social experience […] historically

distinct from other particular qualities, which gives the sense of a

generation or of a period.” [2] Metamodernism therefore is both a

heuristic label to come to terms with recent changes in aesthetics and

culture and a notion to periodize these changes. So when we speak of

metamodernism we do not refer to a particular movement,

a specific manifesto or a set of theoretical or stylistic

conventions. We do not attempt, in other words, as Charles Jencks would

do, to group, categorize and pigeonhole the creative work of this or

that architect or artist. [3] We rather attempt to chart, after Jameson,

the ‘cultural dominant’ of a specific stage in the development of

modernity. [4]

Our methodological assumption is that the

dominant cultural practices and the dominant aesthetic sensibilities of a

certain period form, as it were, a ‘discourse’ that expresses cultural

moods and common ways of doing, making and thinking. To speak of a

structure of feeling (or a cultural dominant) therefore has the

advantage, as Jameson once explained, that one does not “obliterate

difference and project an idea of the historical period as massive

homogeneity. [It is] a conception which allows for the presence and

coexistence of a range of very different, yet subordinate features.” [5]

These different, yet subordinate features

can alternatively be described as ‘residuals’ of days gone by or as

‘emergents’ that point to another day and age. [6] Postmodernism might

have passed, it might have “given up the ghost”, but, as Josh Toth

rightly argues, to speak of its death is to also speak of its afterlife.

“The death of postmodernism (like all deaths) can also be viewed as a

passing, a giving over of a certain inheritance, that this death (like

all deaths) is also a living on, a passing on.” [6] The spectre of

postmodernism – but also that of modernism – still haunts contemporary

culture.

Others have started to theorise emergent

structures of feeling that might, or might not, become dominant in the

(not so near) future. The most obvious examples of such an emergent are

all those practices that have become associated with the commons. Several theorists have argued, for instance, that these practices, ultimately, point towards an altermodernity, a future beyond modernity as we currently know

it. Whether or not we agree with these visions of the future is besides

the point here. What matters is that it is our contemporary culture

that enable these visions; or rather, that opens up the discourse of

having a vision at all.

Metamodernism, as we see it, is neither a

residual nor an emergent structure of feeling, but the dominant cultural

logic of contemporary modernity. As we hope to show in this webzine,

the metamodern structure of feeling can be grasped as a generational

attempt to surpass postmodernism and a general response to our present,

crisis-ridden moment. Any one structure of feeling is expressed by a

wide variety of cultural practices and a whole range of aesthetic

sensibilities. These practices and sensibilities are shaped by (and

shaping) social circumstances, as much as they are formed in reaction to

previous generations and in anticipation of possible futures. We

contend that the contemporary structure of feeling evokes a continuous

oscillation between (i.e. meta-) seemingly modern strategies and ostensibly postmodern tactics as well as a series of practices and sensibilities ultimately beyond (i.e. meta-) these worn out categories.

The metamodern structure of feeling evokes

an oscillation between a modern desire for sens and a postmodern doubt

about the sense of it all, between a modern sincerity and a postmodern

irony, between hope and melancholy and empathy and apathy and unity and

plurality and purity and corruption and naïveté and knowingness; between

control and commons and craftsmanship and conceptualism and pragmatism

and utopianism. Indeed, metamodernism is an oscillation. It is the

dynamic by which it expresses itself. One should be careful not to think

of this oscillation as a balance however; rather it is a pendulum

swinging between numerous, innumerable poles. Each time the metamodern

enthusiasm swings towards fanaticism, gravity pulls it back towards

irony; the moment its irony sways towards apathy, gravity pulls it back

towards enthusiasm.

REFERENCES

[1] In Digimodernism. How new technologies dismantle the postmodern and reconfigure our culture.

Alan Kirby makes a similar observation concerning the end of

postmodernism and the emergence of network culture. Although his book is

insightful and provocative, he tends to be wholly negative, ignoring

the paradoxes and potentialities of network culture.[2] Raymond Williams (1977). Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 131

[3] See, for example: Charles Jencks (1977). The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. New York: Rizzoli.

[4] Jameson, too, uses William’s conception of a structure of feeling to conceive of his notion of a cultural dominant.

[5]M. Hardt and K. Weeks. (2000). The Jameson Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp, 190-191.

[6] R. Williams, p. 122

[7] J. Toth (2010). The Passing of Postmodernism.

New York: State University of NewYork, p. 2

The

prefix ‘meta’ has acquired something of a bad rep over the last few

years. It has come to be understood primarily in terms of

self-reflection – i.e. a text about a text, a picture about a picture,

etc. But ‘meta’ originally intends something rather more colloquial. According to the Greek-English Lexicon the preposition and prefix ‘meta’

(μετά) has several meanings and connotations. Most commonly it

translates as ‘after’. But it can also be used to denote qualitative

‘changes’ or to designate positions such as ‘with’ and ‘between’. In

Plato’s Symposium, for example, the term metaxy designates an

ontological betweenness (we will return to this in more detail in a

later post).The Online Etymology Dictionary gives the following description:

prefix meaning 1. “after, behind,” 2. “changed, altered,” 3. “higher, beyond,” from Gk. meta (prep.) “in the midst of, in common with, by means of, in pursuit or quest of,” from PIE *me- “in the middle” (cf. Goth. miþ, O.E. mið “with, together with, among;” see mid). Notion of “changing places with” probably led to senses “change of place, order, or nature.

When we use the term ‘meta’, we use it in similar yet not indiscriminate fashion. For the prefix ‘meta-’allows us to situate metamodernism historically beyond; epistemologically with; and ontologically between the modern and the postmodern. It indicates a dynamic or movement between as well as a movement beyond. More

generally, however, it points towards a changing cultural sensibility –

or cultural metamorphosis, if you will – within western societies.

How PoMo Can You Go ?

It was considered the End of Modernism, the beginning of a new era of content, irony, appropriation. So what ever happened to Postmodernism?

Featured in the “New Wave Section” of the “Postmodernism” show is Cinzia Ruggeri’s dress design Hommage à Lévi-Strauss, 1983

STEPHAN RAPPO/©SWISS NATIONAL MUSEUMFor many, Postmodernism began with architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s epiphany: Las Vegas is our Versailles. Their book Learning from Las Vegas was published in 1972, just a few years after the widespread student protests, counter-culture communes, and dropouts of 1968 had signaled opposition to the Modernist belief system. By the late ’70s, Charles Jencks’s theoretical texts had appeared, and so had Frank Gehry’s radically deconstructed renovation of his own house in Santa Monica. Postmodern piazzas and colonnades began emerging, along with oxidized copper trim. But what got the most attention was a Midtown New York skyscraper with a Chippendale pediment—the AT&T building, designed by a former glass-box Modernist, Philip Johnson.

In art, which adapted Postmodernism to its own ends, things were less simple. By 1969, Earthworks, scatter-works, Conceptual art, and Duchamp’s Étant donnés—his disturbingly real peephole landscape diorama that embodied what his symbolic bachelors did to the formerly disembodied bride—had changed the nature of advanced art. A startling image of a vulnerable blue Earth taken from the moon seemed to predict a new art of natural substances, ongoing processes, illusory images, and real-time systems. Ransacking, recycling, scavenging, and appropriating from the real world, many artists at that time also seemed to be abandoning abstraction and geometry.

Among the first to be considered Postmodern were the highly politicized San Diego narrative Conceptualists and video artists of the ’70s: Martha Rosler, Eleanor Antin, Helen and Newton Harrison, and Suzanne Lacy among them. While Rosler was merging Vietnam war scenes with suburban living rooms in photocollages or mailing recipe postcards that targeted class disparities, Antin was sending postcards across the U.S. of 100 disembodied boots on their way to war. And while the Harrisons were mapping polluted waterways, Lacy pinpointed the sites of rapes in L.A. on a five-part feminist map. By 1980, Postmodernism—which had started as an insurrection against the worn-out abstract strategies of the New—had become a controversial theory that set academics off hurling insults at one another about whether Modernism would ever end or whether it was already kaput.

At around the same time, painting returned from its stupor in a dizzying array of disguises: New Image painting (Jennifer Bartlett and Robert Longo, for instance), Pattern and Decoration (Robert Kushner and Kim MacConnel), the Italian transavantgarde (Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi, and Francesco Clemente), the German painters (Georg Baselitz and Jörg Immendorff), and the Neo-Expressionists, chief among them David Salle. Julian Schnabel straddled the fence—his crockery and paintings on Japanese backdrops were obviously Postmodern, but his swashbuckling paint was, arguably, a Modernist throwback.

Apart from Cindy Sherman, who became the quintessential Postmod poster girl, it was a thorny question of who was and was not PoMo. When appropriation art appeared, and Richard Prince (with his rephotographed Marlboro Man) and Sherrie Levine (with her play-it-again Walker Evans photos) began squabbles over who had been the first to abandon the Modernist dictum of Make It New, PoMo went retro (this stage was later dubbed the Pictures Generation). By the end of the ’80s, the terms were multiplying: post-Postmodernism, Supermodernism, Hypermodernism, Neo-modernism, Anti-modernism, Altermodernism. The one thing everyone seemed to agree about was the major role being played by irony and pastiche.

During the 1990s, Postmodernism got swallowed whole by all the things it had spawned: multicultural art, feminist projects, politicized photoworks, and installations about gender, race, ethnicity, and the Other.

Now, some 20 years later, the ghost of Postmodernism has returned. What once was a radical concept in Western culture that dominated avant-garde discourse for nearly two decades—and signaled a shift from analysis to synthesis, from grids to maps, from the shock of the new to the retrieval of the old—has resurfaced as nothing more than a decorative style that is basically an update of Art Deco.

This revival re-emerged last autumn, spearheaded by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which mounted a major design exhibition, “Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990.” The show, which is at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich through October 28, treats Postmodernism not as an inevitable earth-shattering, paradigm-shifting movement but as just another style trend, like Punk or Goth. It features Memphis furniture, Vivienne Westwood fashions, the Alessi teapot, and Grace Jones’s cubistic maternity dress.

Meanwhile, in the United States, there were clashes between PoMo and Promo factions about whether Postmodernism really was a style. In contrast to when it first appeared, this resuscitated Postmodernism was mostly about decor and argument. At its start, it seemed to slice through history, announcing the finality of the modern tradition as well as its own moral quest for content, context, and substance in the pre-digital world of its day. Today, in our thoroughly fragmented, commodified, and fetishized early 21st century, the update becomes a farce, having everything to do with stylishness and inclusiveness, and nothing to do with substance. “Postmodernism is a sort of early warning system for the lives we lead now,” said Glenn Adamson, cocurator with Jane Pavitt of the V&A design show, which not only included Kraftwerk, but also hip-hop performers and even the dissident art hero of 2011, Ai Weiwei. “Singapore, Beijing, and Dubai are arguably more Postmodern now than Milan and London ever were.” But this is what happens: the radical fringe becomes the dominant look. The profound concept becomes a matter of shallow surfaces. And that’s exactly how Postmodernism ended up.

In the past couple of years, there’s been a new post-Postmodern movement lurking in Europe: Metamodernism. It features an agenda that involves art that is impermanent, incremental, provisional, and idiosyncratic, as well as site-specific and performative, emotive and perceptual, devious and questioning.

Advanced by cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, who have published Notes on Metamodernism as a webzine, Metamodernism neatly negotiates the built-in confusions and contradictions between Modernism and Postmodernism. Vermeulen and van den Akker propose that “the Postmodern culture of relativism, irony, and pastiche” is finished, having been replaced by a post-ideological condition that stresses engagement, affect, and storytelling. “Meta,” they note, implies an oscillation between Modernism and Postmodernism and therefore must embrace doubt, as well as hope and melancholy, sincerity and irony, affect and apathy, the personal and the political, and technology and techne (which is translated as “knowingness”).

Sense and nonsense play a role, too. So does quirkiness. In the foreground today are such so-called Metamodernists as Ragnar Kjartansson, Pilvi Takala, and Cyprien Gaillard, all of whom work in Berlin and whose work is characterized by a fluid esthetic that refers to nostalgia, make-believe, and old-fashioned painting as if it were performance. Kjartansson, who performs musically as well, painted one portrait a day of a friend in a Speedo swimsuit for the 2011 Venice Biennale. Takala’s video intervention in an office job, shown in the “Ungovernables” exhibition at the New Museum, followed the artist as she pretended to do nothing for days on end—a bewilderingly sincere performance that questioned the concept of labor. And Gaillard, interested in the concept of failure, combines picturesque romanticism and entropic Land Art, setting off fire extinguishers in the landscape, recording the rubble of demolished modern buildings, and commissioning landscape paintings. In the work of these artists, reality, fiction, old-fashioned representation, and recent relational strategies come to terms with failure, instability, and all the looming “as ifs” of the present moment.

Over the last few months, there has been

much discussion online as well as at parties, galleries and

conferences, about the meaning of the prefix meta- in metamodernism.

Now, of course, each and everyone is free to define, re-appropriate and

use it in any one fashion. Metamodernism as a term – but not as a

concept – is or has been associated with altermodernism, reflective

modernism, reflexive modernism, and a counterstrategy within modernism.

And it has been applied to developments and disciplines as diverse as

economics, politics, architecture, data analysis, and the arts. But (or

So) we feel compelled to once more establish what WE mean with the

prefix meta – and, perhaps even more important, what we do not intend by

it. In a previous post we described it as follows:

The prefix ‘meta’ has acquired something of a bad rep over the last few years. It has come to be understood primarily in terms of self-reflection – i.e. a text about a text, a picture about a picture, etc. But ‘meta’ originally intends something rather more colloquial. According to the Greek-English Lexicon the preposition and prefix ‘meta’(μετά) has several meanings and connotations. Most commonly it translates as ‘after’. But it can also be used to denote qualitative ‘changes’ or to designate positions such as ‘with’ and ‘between’. In Plato’s Symposium, for example, the term metaxy designates an ontological betweenness (we will return to this in more detail in a later post). The Online Etymology Dictionary gives the following description:

prefix meaning 1. “after, behind,” 2. “changed, altered,” 3. “higher, beyond,” from Gk. meta (prep.) “in the midst of, in common with, by means of, in pursuit or quest of,” from PIE *me- “in the middle” (cf. Goth.miþ, O.E. mið “with, together with, among;” see mid). Notion of “changing places with” probably led to senses “change of place, order, or nature,”

When we use the term ‘meta’, we use it in similar yet not indiscriminate fashion. For the prefix ‘meta-’ allows us to situate metamodernism historically beyond; epistemologically with; and ontologically between the modern and the postmodern. It indicates a dynamic or movement between as well as a movement beyond. More generally, however, it points towards a changing cultural sensibility – or cultural metamorphosis, if you will – within western societies.Thus, although meta has come to be associated with a particular reflective stance, a repeated rumination about what we are doing, why we are doing it and how we are doing it, it once intimated the movement with and between what we are doing and what we might be doing and what we might have been doing. When we use the prefix meta- we do NOT refer to the former meaning. Meta- for us, does NOT refer solely to reflectivity, although, inevitably, it does (and, since it passes through and surpasses the postmodern, cannot but) invoke it.

When we use the prefix meta- we refer to the latter intent. Meta, for us, signifies an oscillation, a swinging or swaying with and between future, present and past, here and there and somewhere; with and between ideals, mindsets, and positions. It is influenced by estimations of the past, imbued by experiences of the present, yet also inspired by expectations of the future. It takes into account and affect the here, but also the there, and what might or might not happen elsewhere. It is convinced it believes in one system or structure or sensibility, but also cannot persuade itself not to believe in its opposite. Indeed, if anything, meta intimates a constant repositioning. It repositions itself with and between neoliberalism and, well, keynesianism, the “right” and the “left”, idealism and “pragmatism”, the discursive and the material, the visible and the sayable. It repositions itself among and in the deconstructed isms and desolate ruins that rest from the postmodern and the modern, and reconstructs them in spite of their un-reconstructableness in order to create another modernity: then one, then the other, one again, and yet another. Bas Jan Ader’s quest for the miraculous, Charles Avery’s quest for an imaginative elsewhere, Mona Hatoum’s search for another socio-personal identity, Sejla Kameric longing for another ethnic-personal epistemology, Mariechen Danz’s longing for the pre-discursive, Ragnar Kjartansson’s desire for what is always just beyond his reach…

Meta- does not refer to one particular

system of thought or specific structure of feeling. It infers a

plurality of them, and repositions itself with and between them. It is

many, but also one. Encompassing, yet fragmented. Now, yet then. Here,

but also there.

Image: Bas Jan Ader, In search of the miraculous.

No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism

Program Description

Introduced as an intervention in the post-modernism debate by cultural theorists Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker in their 2009 essay “Notes on Metamodernism,” metamodernism asserts that the 2000s where characterized by the return of typically modern positions without altogether forfeiting the postmodern mindsets of the 1990s and 1980s.

Showcasing this emerging discourse, the cinema program No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism pairs cinema works, all produced in the 2000’s, with free copies of Van den Akker and Vermeulen’s essay. Hailing from different countries, these artworks all illustrate Van Den Akker and Vermeulen’s tenants metamodernism being “a continuous oscillation, a constant repositioning between positions and mindsets that are evocative of the modern and of the postmodern but are ultimately suggestive of another sensibility that is neither of them. A discourse that negotiates between a yearning for universal truths but also an (a)political relativism, between hope and doubt, sincerity and irony, knowingness and naivety, construction and deconstruction.”

Van Den Akker and Vermeulen suggest that the metamodern attitude longs for another future, another meta-narrative, while simeltaniously acknowledging that that this future or narrative might not exist, or materialize, or, if it does materialize, is inherently problematic.

Even this program’s title, No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernsim, oscillates between a proclamation of earnest desire to break from the history of modernism while also acknowledging the irony in the impossibility of such a quest. Together these works present this recent skeptical, but hopeful, turn in critical theory and cultural production. No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism showcases a sampling of works that present a new perspective in contextualizing our world in the new millennium.

No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism will be on view in the Theater at MAD all day during normal museum hours, with occasional interruption by additional programs

No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism is organized by Jake Yuzna, Manager of Public Programs with assistance from Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker.

No More Modern : Notes on Metamodernism is presented in response to the exhibition Crafting Modernism: Midcentury American Art and D

Now, the metamodern too is expressed through a variety of mind-sets, practices, art forms, media and genres. Certainly, it has been expressed most visibly in the emergence of a New Romanticism. Artists such as Olafur Eliasson, Gregory Crewdson, Kaye Donachie, and David Thorpe, and architects like Herzog & de Meuron no longer merely deconstruct the commonplace, but seek to reconstruct it. They exaggerate it, mystify it, alienate it. But with the intention to resignify it. With the intention to create within the commonplace an uncommonspace. Many of these artists draw on the philosophies of Schlegel and Novalis. Many refer to the paintings of Friedrich and Böcklin. Some return, significantly, to figurative practices. Their works show grandiose landscapes, ruins, lonely wanderers. (As an aside, it was this ‘movement’ that initially drew our attention to the decline of the postmodern and the rise of something else. We will come to discuss the New Romantic and its relationship to early German Romanticism in much more detail later this week.)

The metamodern sensibility has further been expressed by what art critic Jörg Heiser has called Romantic Conceptualism.

Heiser defines Romantic Conceptualism as a tendency within both recent

and past conceptual art that replaces the rational with the affective

and the calculated with the coincidental. It is also expressed in

Performatism. The German scholar Raoul Eshelman defines Performatism

as an act of ‘wilful self-deceit’. It is the enactment of a truth that

cannot be true, the establishment of a holistic, coherent identity that

cannot exist. Eshelman refers to works and texts as varied as the

architecture of Kleihues, Yann Martel’s Pi, and Amélie. In cinema, it is

articulated first and foremost in quirky. James MacDowell will write a

post on this trend associated with the informed naivety of films such as

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Rushmore and Juno later in the

week. In pop music, it is articulated in the freak folk of Antony and

the Johnsons, Akron Family and Devendra Banhart, but also in the

heartfelt ballads of Best Coast. It is articulated in trends such as

Remodernism, Reconstructivism, the New Sincerity and Stuckism. In unique

works of artists and authors as varied as Ragnar Kjartansson, Mariechen

Danz, Roberto Bolano and maybe even Dave Eggers. And just think of

developments like the restructuration of the financial system, Obama’s

‘Yes we can!’, and environmentalism. And so on and so forth.

The metamodern sensibility has further been expressed by what art critic Jörg Heiser has called Romantic Conceptualism.

Heiser defines Romantic Conceptualism as a tendency within both recent

and past conceptual art that replaces the rational with the affective

and the calculated with the coincidental. It is also expressed in

Performatism. The German scholar Raoul Eshelman defines Performatism

as an act of ‘wilful self-deceit’. It is the enactment of a truth that

cannot be true, the establishment of a holistic, coherent identity that

cannot exist. Eshelman refers to works and texts as varied as the

architecture of Kleihues, Yann Martel’s Pi, and Amélie. In cinema, it is

articulated first and foremost in quirky. James MacDowell will write a

post on this trend associated with the informed naivety of films such as

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Rushmore and Juno later in the

week. In pop music, it is articulated in the freak folk of Antony and

the Johnsons, Akron Family and Devendra Banhart, but also in the

heartfelt ballads of Best Coast. It is articulated in trends such as

Remodernism, Reconstructivism, the New Sincerity and Stuckism. In unique

works of artists and authors as varied as Ragnar Kjartansson, Mariechen

Danz, Roberto Bolano and maybe even Dave Eggers. And just think of

developments like the restructuration of the financial system, Obama’s

‘Yes we can!’, and environmentalism. And so on and so forth.Some might argue that this multiplicity of strategies expresses a plurality of structures of feeling. However, what they have in common is a typically metamodern oscillation, an unsuccessful negotiation, between two opposite poles. In, say, Bas Jan Ader’s attempts to defy the cosmic laws and the forces of nature, to make the permanent transitory and the transient permanent, it expresses itself dramatically, as a struggle between life and death. In, for example, Justine Kurland’s efforts to present the ordinary with mystery and the familiar with the seemliness of the unfamiliar it exposes itself less spectacularly, as the unsuccessful negotiation between culture and nature. But both these artists set out to fulfill a mission or task they know they will not, can never, and should never accomplish: the unification of two opposed poles. And both are concerned with Novalis: the opening up of new lands in situ of the old. Odd new lands. Untenable new lands. But new lands nonetheless.

Over the next weeks, months, years we will try to discuss and draw your attention to as many metamodern strategies as we possibly can. Strategies that we feel, whatever their disparate intentions and dissimilar interests, all have the oscillation between the modern and the postmodern at its heart. We will discuss the New Romantic later this week. Quirky the next. Performatism after that. Some might be a bit more than metamodern; others might be somewhat less. You might disagree with any one of them. Please feel free to challenge us! If metamodernism is an oscillation rather than a balance, an ongoing discussion without answer, then so is this blog.

Top left image: Justine Kurland, West of the Water (2003). CourtesyMitchell-Innes & Nash

Bottom right Image: Mariechen Danz, Ye (2006). Courtesy Galerie Tanja Wagner

Postmodernism announced the death of the

subject, but recent developments in literature, philosophy and political

agency suggest that it is alive and kicking as ever. Not in form of the

modern Cartesian ego though and also not in denial of all the

subjectivity-disrupting forces that postmodern theory pointed out. It

returns with a great leap of faith, in a fragile moment of

intersubjective trust and reveals characteristic traits that call for

another vernacular, one that this webzine has come to describe as

metamodern.[i]

“A prevalent discourse of a recent epoch concludes with its [the

subject’s] simple liquidation”, states Jacques Derrida in an interview

with Jean-Luc Nancy. The “recent epoch” Derrida is talking about is

postmodernism, of course. And who would know better what postmodernism

is about than the wizard of postmodern thought himself? In a discourse

that casts doubt on the credulity of metanarratives, that questions the

hermeneutics of meaning, the rational, self-contained subject of

modernism has had a hard time indeed.For the subject at stake here, the

subject allegedly liquidated in postmodernism, is the modern subject.

Its beginnings can be traced back to sometime around the Renaissance and

Reformation, but it is most commonly characterized in terms of the

Cartesian Ego: it is strong, autonomous, reasonable and above all

coherent. It has cast off determination by church doctrine and

Christianity`s encompassing truths and instead goes for, as Heidegger

puts it, “legislating for himself”[ii].Postmodernism then dismantles and deconstructs all the grand-narratives and overriding truths, only this time this affects not only the grand-narrative of religion, but also the subject itself, whose status as a rational entity is seen as another grand-narrative. Backed by post-structural linguistics, the different postmodern/poststructuralist thinkers, such as Foucault, Althusser or Lacan, are taking a tough stance towards the subject and are exposing it as foreign-ruled, schizophrenic, instable, a field of discourses.The skepticism against metanarratives remains one of the greatest achievements of postmodern thinking, changing not only the face of philosophy, but influencing profoundly such fields as identity and gender politics, backing disability studies, triggering post-colonial studies and bringing the project of multiculturalism to life.

These achievements remain unchallenged. Nevertheless, over the last ten years, quite astonishing changes have happened, for instance in terms of discussing subjectivity in academia. Across a variety of disciplines – literary studies, philosophy, political theory and even psychology – calls for a rethinking of subjectivity can be heard. Publications dealing with “The return of the subject” or “The Self beyond the Postmodern Crisis“, suddenly become ubiquitous.

But also in literature, film, arts and political agency, we can witness a paradigm shift. The subject reappears and it comes with other dismissed categories such as trust, belief, coherence and even love. I would suggest that it reappears in a confined space that Peter Sloterdijk in his “Spherology” describes as a “Bubble” – an artificially created space, where in a human, intersubjective experience, the outside forces exposed by postmodern thinkers can be temporarily shut out.

In Performatism or The End of Postmodernism, the literary scholar Raoul Eshelman depicts a new kind of subject that establishes itself in spite of disruptive forces in an act of belief. This subject is a coherent self that re-introduces the possibility for identification, affection and selfhood, although not in a naïve, unreflective way.

Similarly, Karen Coats assures that there is no way the Cartesian Ego can return after all that was learned from Postmodernism – only to then sling the slogan “I love, therefore I am” into the arena of debate, calling for a rethinking of the concept of the Self, acknowledging the role of love in its construction. The writings of Lebanese-French author Amin Maalouf ask for a rethinking of the concept of identity describing it as an act of positive affirmation, which can include an attachment to a religion or land or ethnic group, while acknowledging the instability of identity as such. And even the great evangelist of postmodernism, Ihab Hassan, suddenly calls for an “Aesthetic of Trust”, where in a “world flow of ultimate mysteries”, the relation between subject and object can be redefined in terms of “profound trust”[iii].

As others have documented on this webzine, in literature as well as film or television, too, we suddenly come to meet characters who masquerade as coherent subjects. They are innovative figures who step into the scene with a quirkiness that, perhaps precisely because of their idiosyncratic authenticity, renders possible a new relation between literary hero and recipient. Furthermore, we experience a shift considering political agency: Wasn’t the subject of Postmodernism (as Slavoij Žižek doesn’t cease to remind us), essentially powerless in the workings of global capitalism? Then the symbol of the OccupyWallStreet-Protests, the fragile, yet brave and daring ballerina on top of the iron bull, definitely proves a new kind of political agent.

While

all of the above mentione fields d are worth taking a closer look at,

it is one artist that best exemplifies, for me, the parameters of the

metamodern subject: Miranda July. Readers of this webzine might know

July from James MacDowell`s articles on the “quirky”

cinematic sensibility, in which MacDowell describes her self-starred

movie “Me and You and Everyone We Know” as one of those post-millennial

American indie comedies that convey a metamodern tone and feeling. This

does not only apply to her films, however. Across the oeuvre of

all-rounder July, we are confronted with moments in which bitter irony

is paired to straight sincerity, fear to trust, and skepticism to

optimism.

While

all of the above mentione fields d are worth taking a closer look at,

it is one artist that best exemplifies, for me, the parameters of the

metamodern subject: Miranda July. Readers of this webzine might know

July from James MacDowell`s articles on the “quirky”

cinematic sensibility, in which MacDowell describes her self-starred

movie “Me and You and Everyone We Know” as one of those post-millennial

American indie comedies that convey a metamodern tone and feeling. This

does not only apply to her films, however. Across the oeuvre of

all-rounder July, we are confronted with moments in which bitter irony

is paired to straight sincerity, fear to trust, and skepticism to

optimism.Central to all her fictional works are characters that can be described –euphemistically – as socially awkward. They are naïve to an extent that one wants to scream at them or simply turn off the TV or throw away the book; they are lonely and desperately looking for love; they are either leading terribly average lives or they are isolated and insecure to such an extent that any glimmer of optimism on their faces can only generate a feeling of pity in the spectator. Yet this doesn’t happen. July’s characters somehow manage to overcome the inescapable trap of postmodern discourse. With all their oddities, they develop a braveness and self-confidence that seems highly unreasonable, preposterous and odd in itself, but nevertheless works for them, enabling temporary, intimate relations with others that convey a great deal of beauty.

In the short-story The Sister, a sex-scene between two lonely old men is doomed by bitter skepticism, repulsion, insecurity and one man’s fear of contracting STDs. This being the “real” that postmodernists loved “rubbing observers’ our noses in“[iv], as Raoul Eshelman describes it. But the two men don’t end up being disrupted by the context, instead develop a fragile mutual understanding and emotional proximity, a space where the subject – for the time being – is safe from contextualization. It is an instance of the modern self that is stabilized despite a postmodern background.

The same strategy can be observed in the relationship between a young boy and an embittered art curator in Me and You and Everyone We Know. Their relationship starts in a chat room, where the infamous line: “I want to poop back and forth, forever” is featured. The forces of discourse just hail down on the two characters, but the sincerity of the little boy and the trust of the older woman manage to form a protective shield against outside forces, leading up to a scene that contributed to the “R-Rating” of the movie in the U.S. This scene shows us two subjects in a sphere where context can get no hold of them: The boy kisses the woman, kind and forward, and she smiles for the first time in the movie. Miranda July’s fiction is full of such moments of tender weirdness.

Her interactive sculpture Eleven Heavy Things similarly deals with this possibility of subjectivity despite a hostile, postmodern context in a very unique way. The Sculpture – originally built for the Venice Biennale and later moved to New York Union Square Park, features a square-white pedestal with black inscription, reading:

This is my little girl. She is brave and clever and funny. She will have none of the problems that I have. Her heart will never be humiliated. Self-doubt will not devour her dreams.At first glance the sculpture recalls the modern subject. It is strong and capable, standing on solid ground. If we were still in the hey-day of modernism, the scripture on the socket supporting whoever stands on it could even be read as a kind of manifesto, a messianic promise. But that is not all there’s to it. While containing space for a belief in the subject, it just as strongly contains space for its dissolution in postmodern irony: self-doubt will not devour your dreams? Seriously? You are a field of energies at the best and a Nothing dissolved in discourse at the worst.

The artwork of Miranda July thus contains, I believe, both a modern and postmodern subjectivity and thus exemplifies the space where an ingenious, metamodern subject can show itself. In this restricted area the subject is characterized by fragile belief that cannot brush aside good old postmodern irony completely – which would dissolve the subject immediately – but keeps it at bay for the moment.The installation enables the creation of a space where love can exist again. As fragile and problematic as it might seem to shut out discourse, it is carried out carefully so it doesn`t fall back into a (modern) fanatic personal-cult.

It is this oscillation between the belief in what is written to be true and the consciousness of it being utterly unlikely that makes for the beauty of the artwork and reflects a feeling that may very well be called metamodern. It is a moment of trust and love despite the harsh reality. It possesses at the same time sincerity and irony. The installation provides us with contained hope that is accompanied by a twitch of melancholy.

The reemerged subject is not the old modern one. It contains no transcendental justifications. Concepts of identity, selfhood and subjectivity can always be dismantled and deconstructed. But while the awareness about this still rightfully persists, new times call us to acknowledge that the subject nevertheless appears, in moments of intersubjectivity, in reciprocal spaces of believe, trust and love.

Top image: courtesy Miranda July. Still from Me and you and everyone we know (2005). Lower image, left: courtesy Adbusters. Occupy-poster What is your one demand? Lower image, right: courtesy Lukas Wassmann. Photo Eleven Little Things.

[i]

The concept of Metamodernism and my understanding of it, is drawn from

articles on metamodernism.com and Vermeulen, Tim and Robin van den Akker

(2010): Notes on Metamodernism, Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, Vol. 2, 2010 DOI: 10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677

[ii] Martin Heidegger, “The Age of the World Picture,” in: The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, Harper and Row, (1977), New York, p. 148.

[iii]

Hassan, Ihab: “Beyond Postmodernism. Toward an Aesthetic of Trust“, in:

Klaus Stierstorfer (Ed.), Beyond Postmodernism. Reassessments in

Literature, Theory and Culture, de Gruyter (2003), Berlin and New York,

p. 211.

[iv] Eshelman, Raoul: “Performatism, or The End of Postmodernism”, in: Anthropoetics – The Electronic Journal of Generative Anthropology, Volume VI, number 2 (Fall 2000/Winter 2001)

http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0602/perform.htm

Sources:

Coats, Karen: ”The Role of Love in the Development of the Self: From Freund and Lacan to Children’s Stories“, in: Paul Vitz and Susan Felch (Ed.), The Self Beyond the Postmodern Crisis, ISI Books (2006), Wilmington.

Eshelman, Raoul: “Performatism or The End of Postmodernism”, Davis Group (2008), Aurora.

Hassan, Ihab: “Beyond Postmodernism. Toward an Aesthetic of Trust“, in: Klaus Stierstorfer (Ed.), Beyond Postmodernism. Reassessments in Literature, Theory and Culture, de Gruyter (2003), Berlin and New York.

Lyotard, Jean-François:” The Postmodern Condition. A Report on Knowledge”, Manchester University Press (1984), Manchester.

Miranda July: “No one belongs here more than you”, Canongate (2007), Edinburgh.

Miranda July: “Me and You and Everyone We Know”, DVD 91 min, IFC (2005)

Sloterdijk, Peter: “Sphären/1. Blasen“, Suhrkamp (1999), Frankfurt a . Main.

http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0602/perform.htm

Sources:

Coats, Karen: ”The Role of Love in the Development of the Self: From Freund and Lacan to Children’s Stories“, in: Paul Vitz and Susan Felch (Ed.), The Self Beyond the Postmodern Crisis, ISI Books (2006), Wilmington.

Eshelman, Raoul: “Performatism or The End of Postmodernism”, Davis Group (2008), Aurora.

Hassan, Ihab: “Beyond Postmodernism. Toward an Aesthetic of Trust“, in: Klaus Stierstorfer (Ed.), Beyond Postmodernism. Reassessments in Literature, Theory and Culture, de Gruyter (2003), Berlin and New York.

Lyotard, Jean-François:” The Postmodern Condition. A Report on Knowledge”, Manchester University Press (1984), Manchester.

Miranda July: “No one belongs here more than you”, Canongate (2007), Edinburgh.

Miranda July: “Me and You and Everyone We Know”, DVD 91 min, IFC (2005)

Sloterdijk, Peter: “Sphären/1. Blasen“, Suhrkamp (1999), Frankfurt a . Main.

Think Occupy Wall St. is a phase? You don't get it

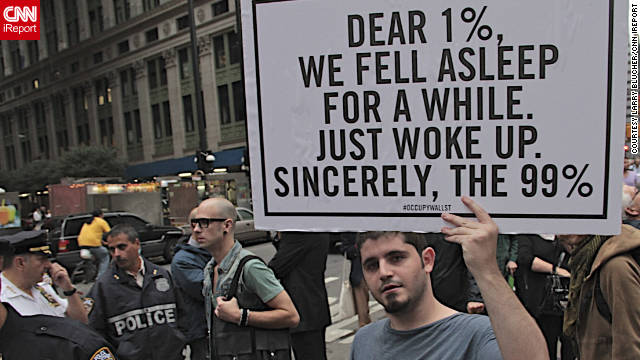

A protester holds a sign at the Occupy Wall Street protest last weekend

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Douglas Rushkoff says traditional media condescends to Occupy Wall Street movement

- He says that's because its 21st-century, net-driven narrative doesn't fit old media model

- He says protest not about end-point, it's about a new discourse on variety of complaints

- Rushkoff: Protest may be unwieldy, but aims to correct disconnects in U.S.

Consider how CNN anchor Erin Burnett, covered the goings on at Zuccotti Park downtown, where the protesters are encamped, in a segment called

"Seriously?!" "What are they protesting?" she asked, "nobody seems to

know." Like Jay Leno testing random mall patrons on American History,

the main objective seemed to be to prove that the protesters didn't, for

example, know that the U.S. government has been reimbursed for the bank

bailouts. It was condescending and reductionist.

More predictably perhaps, a Fox News reporter appears flummoxed in this outtake from "On the Record,"

in which the respondent refuses to explain how he wants the protests to

"end." Transcending the shallow partisan politics of the moment, the

protester explains "As far as seeing it end, I wouldn't like to see it

end. I would like to see the conversation continue."

To be fair, the reason

why some mainstream news journalists and many of the audiences they

serve see the Occupy Wall Street protests as incoherent is because the

press and the public are themselves. It is difficult to comprehend a

21st century movement from the perspective of the 20th century politics,

media, and economics in which we are still steeped.

Occupy protests spread across U.S.

Occupy protests spread across U.S.

Unions join 'Occupy Wall Street'

Unions join 'Occupy Wall Street'

In fact, we are

witnessing America's first true Internet-era movement, which -- unlike

civil rights protests, labor marches, or even the Obama campaign -- does

not take its cue from a charismatic leader, express itself in

bumper-sticker-length goals and understand itself as having a particular

endpoint.

Yes, there are a wide