Tko ovo još nije vidio, ima se čemu veseliti. Tajlandski nadrealni western u pastelnim bojama, pastiš, kričava melodrama, psihodelični operetni urlik: ฟ้าทะลายโจร, ili Fa Thalai Chon, tj. Suze crnog tigra.

cijeli film:

Tears of the Black TigerPeter Bradshaw

You've heard of the spaghetti western - this is the stir-fry horse opera. Here's the uproarious high-camp cowboy drama from Thailand that wowed us all at Cannes. It's bizarrely stylised, boasting melodramatic over-acting, giant emotional close-ups, screechingly villainous laughter, with tense stand-offs and gory shoot-outs borrowed from Peckinpah and Leone. The whole thing looks like a silent movie with spoken dialogue, and the super-saturated colour tones and cheekily obvious sets make it look like an old black-and-white movie that's been "colorized" for American TV.

Director Wisit Sartsanatieng assures us it's a pastiche of Thai western styles. Most of us will have to take his word for that; often it just looks like it's in a barking world of its own. And most surreally of all, during sentimental scenes it uses music that sounds exactly like the Hovis ad theme. ("Ey oop lad, ah remember wheeling t'bike oop cobbled 'ill, on me way to a violent homoerotic shoot-out wi' Thai cowboys".)

It's got a weird charm, but it needs a loudly enthusiastic audience to keep it galloping along.

Without an intimate familiarity with 1960s Thai cinema, it's difficult to discern when Wisit Sasantieng's Tears of a Black Tiger—shot in the old-fashioned style of his country's florid melodramas—is merely being faithful to its cheesy forerunners and when it's deliberately exaggerating their tacky tropes for comedic and/or analytic effect. Replicating Thai genre films' overblown amalgamation of western-movie elements, Sasantieng's directorial debut (completed in 2000, but only now receiving a U.S. release) is part tearjerker, part spaghetti western, and all kinds of crazy, full of tobacco-spitting banditos and set in a bizarre, self-consciously artificial Thai countryside created with overripe colors, rear-projection backdrops, and theatrical lighting. This hyper-real aesthetic is matched, extreme for extreme, by Sasanatieng's story about the ill-fated relationship between criminal gunslinger Black Tiger (Chartchai Ngamsan) and wealthy beauty Rumpoey (Stella Malucchi), who fell in love as kids despite hailing from different sides of the tracks and find their adult reunion complicated by his most-wanted status and her impending marriage to a police captain (Arawat Ruangvuth) intent on shutting down the operation of Black Tiger's kingpin boss Fai (Sombati Medhanee). As the two pine for one another, narrative threads become tangled in excessively contrived ways, but despite the minor amusement derived from the film's fundamentally synthetic construction—which also includes gory slow-motion images of men being peppered with lead, highlighted by an extreme close-up of a bullet traveling through the hole in a coin and into a poor soul's mouth—there's a frustrating lack of excitement or romance to the stylized, Leone-by-way-of-Sirk action. What Tears of the Black Tiger does have is an atmosphere of hallucinatory unreality as well as some choice parodies of its cowboy ancestors, such as Black Tiger associate/rival Mahesuan's (Supakorn Kitsuwon) booming voice—dubbed via reverb-afflicted ADR—and perpetually raised eyebrow. Where the playful caricature ends and any potential critical commentary about its source material begins is ultimately never quite clear. I'm pretty sure, however, that regardless of any deeper significance, the dancing, grenade-throwing midget is meant to be hilarious.- Nick Schager

How about a Thai cult film???

In the mood for a Spaghetti Western? How about a musical? A romantic tearjerker? Well you can have all of that in the Thai cult film, Fai Talai Jone also known as Tears Of The Black Tiger. With Citizen Dog now under his belt, Wisit Sasanatieng's first film is a memorable one.

It's raining steadily and a woman in a bright 1940s magenta dress is walking with an umbrella, across a wooden walk way in a picturesque green lotus-filled pond to a white gazebo that has a rooftop matching her dress. Meanwhile, two Cowboys are trying to get into a bungalow that has been raided with bad guys. The cowboys all of a sudden dash in, bullets start trailing them, and they eventually make it to the porch. Dum, dressed all in a black with a shoulder holster, draws and close-ups of his pistol are quickly cut in as he blast his way into one of the rooms only to spot a bad guy hiding behind a post through a mirror hanging right in front of him. Dum draws his pistol, but then decides to aim at something else, with the bullet ricocheting off a lantern, bucket, shovel, tool box, a dancing toy figure, a light fixture, eventually landing through the bad guy's forehead.

Too fast for you? Well, Sananatieng does us all a favor and shows everything in slow motion. With a well-developed plot line about the tortured romance of Dum and Rumpooey, scenes like this will lead viewers into wanting more. Visually ornamental with the highly stylized set design and stunning shots in pastel colors, stills from the film could pass as Monet paintings. Check out the screen shots and then try to get a hold of the film.

www.fixins.com/

Paint your dragon, cowboy

Saddle up for a gaudy Thai western with acid-trip backdrops and a dash of Bollywood kitsch

Thailand has stood in for so many other places in American thrillers and war movies (most especially Vietnam) that it was an odd experience to see last month the first Thai movie to be distributed in Britain - Iron Ladies, a touching docu-drama about gay volleyball players. Now, before the silly season is over, the second Thai movie to be shown here, the Asian western Tears of the Black Tiger, is getting a much wider release in a couple of dozen cinemas, not all of them art houses.

There has been over the past half-century a profitable two-way traffic between the Hollywood western and the oriental action movie, and Tears of the Black Tiger brings together the western, the all-stops-out Bollywood epic and the popular Thai movie genre of 50 years ago, popularly known as 'Raberd poa, Khaow pao kratom', which translates, apparently, as 'Bomb the mountains, Burn the huts'. The setting is unruly rural Thailand some time in the now distant mid-twentieth century. As in a Tinseltown B-movie of the sort that was then dying out in the States, there is no distinction between the present and a mythical past.

In those old Gene Autry and Roy Rogers pictures, cowboys pursued cattle and villains on horseback, but there were cars and planes around and the girls were dressed in modern styles. In Black Tiger, bandits recruited from the peasant class dress in fancy shirts with pearl buttons and piping, as if spending a holiday at a dude ranch or playing in a bluegrass band. Their enemies, the police, carry machine guns, fire bazookas, drive Jeeps and wear uniforms that resemble those of the Mexican Federales.

At the centre of the story is the doomed love affair between the gorgeous Rumpoey, daughter of a rich landowner, and the peasant lad Seua Dum, known as 'Black Tiger', a leading bandit and blood brother to the vicious gunslinger Mahesuan. Seua Dum is gagged by the old school Thai, and the girl's father prefers a fiancé like police captain Kumjorn, who has sophisticated lines such as: 'I'll take you for a spin in my MG.'

In flashbacks we see them being driven apart by their families, Rumpoey giving the future Black Tiger a harmonica as a souvenir. This harmonica is intended to suggest the one owned by the peasant avenger played by Bronson in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West, the pre-credit sequence of which is recapitulated in Tears of the Black Tiger. The film's score also uses pastiches of Ennio Morricone's western scores, along with Dvorak's elegiac 'Goin' Home' theme from his New World Symphony, and mournful Thai love songs with refrains like 'My soul has died with my heart'.

The violence is deliberately excessive, with slow-motion massacres and spurting blood à la Peckinpah, women clubbed in the stomach, and a surreal scene (borrowed from Sam Raimi's The Quick and the Dead) of two bullets heading towards each other from guns fired by the hero and his rival. This is set against a calculatedly artificial style that employs outlandishly painted backdrops and garish acid colours, recalling old Asian movie posters and making the heroine's large, pink lips look as if they're about to explode.

The overall effect is hallucinatory, as if we're experiencing someone else's druggy dream, and it is far removed from the graceful world of Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the surprise success of which the distributors evidently hope to emulate.

One man's popular retro entertainment is another man's laughable kitsch, and yet another man's knowing postmodernism. You pay your bahts at the box office and you takes your choice.

Thai Cowboys With Rockets

Tears of the Black Tiger is a mind-blowing (literally) mash-up of a movie. Plus: Playgirl bunny Renée Zellweger.

|

(Photo: Courtesy of Film Forum)

|

It’s fun to watch non-American directors translate American genre movies into their own language, American directors translate them back, and non-Americans remix those re-translations, adding dollops of indigenous culture … and then wind up with whacked-out genetic mutations like Tears of the Black Tiger, which its distributor is marketing, quite rightly, as “a candy-colored cowboy cult confection from Thailand.” The only thing missing from that description is an exclamation point. Is it possible to evoke this movie without invoking two dozen others? The director, Wisit Sasanatieng, cites fifties Thai Westerns and a strain of sixties Thai action cinema (Raberd poa, Khaow pao kratom, or “Bomb the mountain, burn the huts”)—and I’ll have to take his word on that. I get a hash of forties cheapie Lash La Rue oaters; florid, wide-screen, Technicolor Douglas Sirk melodramas; lyrical Sergio Leone spaghetti Westerns; homoerotic John Woo gangster shoot-’em-ups; and even George A. Romero splatterfests. I used to make jokes about a hack critic who dubbed Diva “a stylish exercise … in style,” but that about sums this one up. It’s synthetic down to its digitized (but shapely) digits.

Tears of the Black Tiger is set in the age of … who knows? Men in wide-brimmed hats gallop around on horseback firing six-shooters, but sundry machine guns and rocket launchers suggest the director’s time frame is a tad loose. Rumpoey (Stella Malucchi), a beautiful young woman in a bright-magenta dress, awaits her true love in a blue-and-red sala (a Thai pergola) in a blue-lit drizzle in the middle of a golden field. While her heart aches, said true love, Dum (Chartchai Ngamsan), is blowing the brains out of a rat who double-crossed his outlaw boss. Most people who write “blowing the brains out” are indulging in hyperbole. That wouldn’t be me. (Later, as a bullet whizzes toward a man’s head, there’s even a split-second insert of a brain to contextualize the subsequent chunk-shower.) It turns out that Dum, a peasant who, as a lad, kept company with the higher-born Rumpoey, is now the fabled desperado Black Tiger—fastest gun in the rice paddy and a Charles Bronson–level harmonica player.

For the first half-hour and change, Tears of the Black Tiger plays like out-and-out camp, especially when Dum’s cohort Mahasuan (Supakorn Kitsuwon) shares the screen—he of the pouffy hair and pencil mustache and nefarious C-movie laugh (“HO-ho-ho!”). But Sasanatieng throws so much at you that conviction—and passion—bleeds through: No one could keep up this sort of barrage without truly believing in the magic of movies. As drama, the film is both rudimentary and convoluted: Girl loves outlaw but is pledged to police captain; softy outlaw saves captain from execution by gang; captain gets jealous (“He owns your heart, but I own your body!”); hundreds die. But the movie is really about arcs of blood; the saturation of color as a girl disappears into a river (the tributaries turn deep red); the smoke that curls out of a gun barrel; the old-fashioned movie-movie whine of bullets as they ricochet; and cowboys glimpsed through each other’s bowed legs against swirls of color. Blue-green, chartreuse, all manner of pinks—I flashed back to picking paint shades for my bathroom. And every now and then there’s a disjunctive note, like the rejoinder before a climactic shootout: “Remember your oath in front of the Buddha!”

Tears of the Black Tiger arrives with many critics prejudiced in its favor: It had a triumphant screening at Cannes in 2001, was promptly snapped up by the voracious Harvey Weinstein, and then disappeared into the Miramax abyss. It’s no buried postmodern masterpiece, but it certainly is a jaw-dropper: a delirium-inducing crash course in international trash.

In Miss Potter, Renée Zellweger has rounded gerbil cheeks and squinched-up eyes; she looks less like Beatrix Potter than a Beatrix Potter illustration. Is there a cottontail wagging under those bustles? As she proved in Bridget Jones’s Diary, she’s in clover playing English girls; she snuggles herself inside her accent and blithely pops out her lines. She’s dear enough to make this nineteenth-century biopic bearable, but you have to love the genre to sit through scene after scene of dialogue like: “Really, Beatrix: What young man is ever going to marry a girl with a face full of mud?” “I have my art and my animals; I don’t need more love than that”—and on and on, in scenes that make their biopic points and then skip biopic-ishly along as characters sputter, “Well, I never!”

Beatrix—as her snobbily snobbish mother (a snob) reminds her endlessly—is unmarried and likely to remain so as long as she’s always painting garden creatures with waistcoats and walking sticks instead of sensibly allowing herself to be courted. But her beasties are her friends, she insists, and by way of illustration the director, Chris Noonan (Babe), brings them to cartoon life, often with a sprinkling of piano keys, like fairy dust. It’s less cloying than it sounds, if only because Mother Potter is so unremittingly ghastly (“This behavior shows scant regard for your father’s money!”) and Father Potter so erratic in his support that there’s always the hope of Beatrix pulling a Lizzie Borden. But Potter’s life was evidently short on ax whacks. We never even have the satisfaction of seeing her scowling publishers—two prigs who accept her book only as a means of occupying their ineffectual younger brother (Ewan McGregor)—beholden to a woman who converses with bunny pictures.

McGregor (Ewan, not Farmer) is insipidly sincere (Why are there so few parts in which he looks at home?), but the movie picks up when his lumbering sister (Emily Watson) arrives in a jacket and tie and denounces all marriage as “domestic enslavement.” Will she and Beatrix find a warren of their own? Alas, there is no Sapphic sisterhood: She confesses to Beatrix that it’s just an act and that she longs for wedded bliss as much as everyone else. The movie substitutes conventional hetero terminal illness. I’ve long held that in biopics there’s no such thing as an insignificant cough; here, the sight of someone in the rain without an overcoat plays like a warrant for execution.

Miss Potter hardly deserves ridicule. It’s sweet with lovely Lake District vistas and a heartfelt endorsement of land conservation. It will certainly play well with older audiences and the kind of adolescent girls who draw faces in their O’s. And I’m happy that Zellweger got to traipse around the verdant English hills and dales hugging a sketchbook to her breast—it’s a nice change from wringing the necks of roosters.

The Verdict on Auschwitz doesn’t sound like much of a cliffhanger. (“Guilty.”) But this three-part German television documentary of the Frankfurt trial that lasted from 1963 to 1965 uses unheard audiotapes of camp survivors and SS men to construct a portrait that transcends even these momentous particulars: of a vast, self-sustaining ecosystem of sadism and greed. The directors, Rolf Bickel and Dietrich Wagner, lead us through the early investigations, the roundup of commandants and guards and medical orderlies, the inducement of victims to return to Germany. The recordings play as the camera roams the modern, empty courtroom: You hear the note of disbelief in the trembling voices of survivors, and the absence of emotion in the tones of the accused—men locked in a denial that seems as much pathological as self-serving. This is what every human with the potential to wield unchecked power should know: that we are capable of anything.

The first Thai film I ever saw, I was captivated initially by the colors.

It's raining steadily, and a woman, dressed neatly in a 1940s magenta dress is walking with an umbrella and a suitcase, across a wood plankway in a vivid green lotus pond to a white gazebo (or sala) with a roof that matches the color of her dress.

She's waiting.

Elsewhere, a couple of 1940s cowboy-looking guys are outside a bungalow, where some bad guys have holed up. There's shooting, disturbing a cow. The guys go in. A bad guy is hiding behind a post, hoping to get the drop on the heroes. The more somber looking of the two -- dressed all in black with a shoulder holster, draws. He aims at the wall, away from the man that's hiding. The bullet richochets around. The man falls dead.

Did you get that? If you missed it, we'll show it to you again, says a bit of advertising-like sunburst text.

The shot is repeated in slow motion, with the bullet bouncing off various things in a Rube Goldberg manner until it goes through the guy's forehead with a big, bloody, red splat. It's a sign of more fun to come.

There's still another bad guy. He's up in the ceiling. He tries to get the drop on the boys. A gun barrel pokes through a hole in the floor. The man in black sees it, pushes his friend out of the way and shoots lead into the ceiling, cutting away a perfect hole for the guy above to fall through.

The man in black is Dum (the Thai word for the color black). His friend, dressed in a bright blue cowboy shirt, is Mahesuan.

Dum's got to run. He must meet the woman. But it's too late. The woman waited long enough. She returns home, heartbroken. She must marry another man -- a man she does not love.

Through this highly stylized tale, that blends bits of Golden Age Thai cinema of the 50s and 60s with the westerns of Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah, we learn about the tortured romance between Dum and the woman, who's name is Rumpoey.

They first met when they were children. Rumpoey, the daughter of a high government official, was visiting the countryside and was hosted by Dum's father, a village headman. An incident in that beautiful, green lotus pond leaves young Dum scarred for life. It also deeply affects the young, bratty Rumpoey. As she matures, her love for Dum grows deeper.

The story of how Dum becomes an ace gun hand, riding with a band of outlaws, is best experienced while watching the film.

The highlights in this film are many. Besides that first display of trick gunplay, there are a couple of battle scenes with the outlaws vs the government's forces -- led by the man Rumpoey is to marry. Just as the outlaws appear to be losing the fight, Dum and Mahesuan show up with a pair of rocket launchers to turn the tide back.

This reminds me of the final battle scene in Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch.

Music is key. Dum has a sad theme. Just like Bronson's character in Once Upon a Time in the West, Dum plays the harmonica, a mournful refrain in remembrance of love lost.

Another giddy, upbeat theme, with whistling and happy violin playing is used when the outlaws are riding their horses across Thailand's Central Plains. The lyrics are quite, sad, however.

The set design is also noteworthy. At one point, Dum is playing his harmonica against an obviously fake, bright yellow sunset. That it was shot on a soundstage is quite apparent.

Appropriately, the acting is all overplayed and theatrical, especially Mahesuan (the versatile Supakorn Kitsuwon from Monrak Transistor). He talks with a booming, bragging manner of speech and carries himself with a swagger. A pencil-thin fake mustache completes the outfit. He laughs a lot -- an evil laugh that is infectious. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!

Another great supporting player is veteran Thai action star Sombat Metanee, who plays Fai, the leader of the outlaw gang.

"Remember Fai's law," he tells his men. "Whoever betrays Fai, dies."

And he laughs. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha!

In once scene Fai proves his point by shooting a traitor. He flips a coin with a hole in it into the air. The the bullet passes through the hole, the man will die. He dramatically turns, draws and fires. Of course the bullet passes through. A brain is shown and then the man's head explodes.

Rumpoey is placed by Stella Malucci, who's costuming and hairstyle are combine to make her an amalgamation of all the great leading lady icons. She's quite the drama queen, always pouting, depressed and crying.

The only one who shows restraint is Dum (Chartchai Ngamsan), who is unerringly stoical and fatalistic (some might say wooden, but I disagree). He keeps it bottled up inside. Okay, sometimes he does go out of control, but it's only when others have provoked him.

Yes, the acting and cornball plot are all so over the top that Fah Talai Jone might be considered satire along with lines of Blazing Saddles. In lieu of a baked beans campfire scene, Dum and Mahasuen pledge their friendship together by getting drunk on snake blood wine in the presence of a Buddha statue. It's another dizzying scene.

Comedy reaches its high point with the character Sgt Yam, a government solider. Sporting a Charlie Chaplin brush moustache and slight build, he's a definite reference to the Little Tramp.

On inspection before the big raid, the little Sgt Yam reports he has seven wives.

"Well, I'm afraid they will all be widows," the inspecting officer says.

Yam proves to be an expert grenade thrower. He tosses one up into a machine gun nest, conks a guy on the head and knocks him out. The grenade doesn't go off.

"Request permission to throw another," says Yam. And he tosses. And the tower blows up in a fireball with a stuntman diving away out of the flames. Spectacular.

The set designs, colors and wide-eyed sensibilities remind me for some reason of Wizard of Oz. I think it was a conscious effort on the part of the director, which he reinforced by including a midget among the extras in the outlaw gang.

This is one movie I can't recommend enough. It's goofy, but so tragic. It's familiar, yet so different. It is indeed, a very special film. - thaifilmjournal.blogspot.com/

A Thai filmmaker's tale of near-epic proportions

Wisit Sasanatieng was thrilled when Miramax nabbed his film, but a showdown followed. It lasted six years.

NEW YORK — "Tears of the Black Tiger," a Thai musical cowboy melodrama that opens in Los Angeles today, is a delirious pastiche that whizzes through as many incongruous genres as it does implausible plot twists. The movie's real-life trajectory -- from festival star to battle-scarred survivor -- is almost as dramatic and convoluted.

Arriving in American theaters nearly seven years after it was completed, it's one of the most notable victims of the old, overspending Miramax, which in the Weinstein era was notorious for acquiring armloads of festival titles and sometimes allowing them to molder in the vaults indefinitely.

The first feature by Wisit Sasanatieng, a former cartoonist and commercials director, "Tears of the Black Tiger" was the most visible manifestation of the renaissance in Thai cinema. (And not just thanks to its retina-searing palette of chartreuse, canary and magenta.) Dormant for years, Thailand's film industry received a jump-start in the late 1990s with the emergence of slick homegrown hits such as the gangster tale "Dang Bireley" and the ghost story "Nang Nak" (both directed by Nonzee Nimibutr and written by Sasanatieng). But it was Sasanatieng's singular directorial debut -- a movie that evokes countless others and is also like nothing else on Earth -- that alerted the Bangkok film community to the potential of an international market.

A fetishistic homage to Thai genre movies of the '50s and '60s, the film was a flop at home. "It was considered an art-house film by the locals," said Kong Rithdee, film critic of the Bangkok Post. But "Tears" started to gain traction on the festival circuit. It received its overseas premiere in the fall of 2000 at the Vancouver International Film Festival, where it won a top prize. By the time it arrived in Cannes the following spring, the film's sales agent, Fortissimo, had successfully orchestrated a feeding frenzy among assembled buyers.

Eamonn Bowles, president of Magnolia Pictures, which is now releasing the film, remembers seeing "Tears" at its first packed Cannes screening. "The saturated color scheme and the incredibly arch nature of the characters and plot were counterbalanced by a seeming earnestness that just had no precedent for me," he said.

When the Weinstein-run Miramax scooped up the film, it caused a tremor in the Thai movie industry. "Everybody was excited," Sasanatieng said. "It was the first time a Thai film had been sold to a big U.S. company."

Since "Iron Ladies," the 2001 comedy about a transgender volleyball team that was the first Thai film to open theatrically in the U.S., several more have followed. The Chicago-educated Apichatpong Weerasethakul is an established art-house favorite with structural enigmas such as "Blissfully Yours" and the Cannes prize winner "Tropical Malady." There has also been more mainstream fare, notably the martial-arts action movie "Ong Bak," starring the muay thai expert Tony Jaa.

But "Tears of the Black Tiger" went unseen (which only increased its cult standing among cinephiles).

The first rumblings of trouble came when Miramax decided to re-cut the film within months of the Cannes purchase. Sasanatieng said he and his producers had been warned of the Weinsteins' penchant for meddling. But, he said, "We were too innocent. We believed that they would respect our work. They told us again and again that everybody at Miramax loved the film so much."

Sasanatieng offered Miramax a shorter edit of "Tears" that he had prepared for some regions (his preferred cut, the one Magnolia is releasing, runs 110 minutes). But it was less the length than the content that troubled the executives.

"They didn't allow me to re-cut it at all," Sasanatieng said. "They did it by themselves and then sent me the tape. And they changed the ending from tragic to happy. They said that in the time after 9/11, nobody would like to see something sad."

Sasanatieng said he responded by sending Miramax another cut that was shorter than theirs, preserving his ending, but that too was rejected. He then attempted to get out of the deal but found he had no recourse.

It was the "horrible version," as he put it, that played at Sundance in 2002. But Miramax, having butchered the film, apparently lost interest and never released it.

This reckless manhandling was not atypical for a company with such profligate buying habits.

"Miramax had an insatiable appetite for anything that appealed to them," Magnolia's Bowles said. "Part of the strategy was probably to keep films with potential upsides away from the competition. There's also the factor of competitive juices coming into play. Being able to quickly snag a film that had a lot of heat on it was, I'm sure, a big factor in its acquisition. They ended up acquiring more films than could be sensibly released."

"Tears" is not the first film that Bowles and Magnolia's head of acquisitions, Tom Quinn, have liberated from the Miramax crypt. In 2005, they bought and released another buried Asian cult item, Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa's techno-horror film "Pulse" (which Miramax had snapped up, also at Cannes in 2001, for the remake rights).

Sasanatieng, who has completed two more films since and is in preproduction on his fourth, is relieved to leave the whole episode behind. "It's strange to have people only now seeing and talking about my first film, but it also makes me happy," he said. "It's like a rebirth."

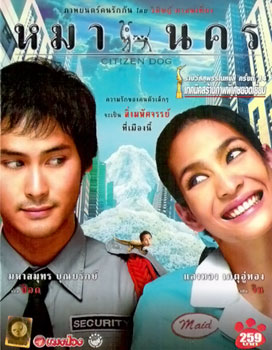

Citizen Dog [Mah Nakorn, หมานคร,] (2004)

Love sends a country-born city boy on a surreal search through the streets of modern-day Bangkok inTears of the Black Tiger director Wisit Sasanatieng's adaptation of wife Koynuch's novel. Despite his grandmother's repeated warnings that he will grow a tail if he moves to the city, country bumpkin Pod (Mahasmut Bunyaraksh) sets his sights on Bangkok and soon lands an assembly-line job. When a factory mishap results in the loss of a finger and Pod opts instead for a job as a security guard, the city-stricken young man soon makes the acquaintance of obsessive/compulsive maid Jin (Sanftong Ket-U-Tong). When Jin is unreceptive to the lovelorn city newcomer's awkward advances, Pod sets out on an enchanting journey through the neon-soaked jungle of Bangkok in hopes of winning the heart of the oblivious object of his affection. www.allmovie.com/

Review: Citizen Dog

- Directed by Wisit Sasanatieng.

- Starring Mahasamuth Boonyarak, Songtong Ket-Utong.

- Released in Thailand cinemas on December 9, 2004.

- Rating: 5/5

First and foremost, Wisit’s world is a colourful place. To the untrained Western eye (like mine) it appears to be influenced by The Wizard of Oz withYellow Brick Road yellows, Dorothy dress blues, Emerald City greens and ruby slipper reds. But really, Wisit's sensibilities are 100 percent Thai. His true influence is the Thai melodramas of the 1950s and 60s -- the true "Golden Age of Thai Cinema" -- something he wanted to recreate in Tears of the Black Tiger and updates in Citizen Dog.

It's a weird world. Red motorcycle helmets rain down from the sky, conking an ironically helmet-less motorcycle taxi driver on the head and turning him into a zombie. There's a cute little girl named Baby Mam who dresses like a stroppy 20-year-old, smokes cigarettes and ignores her teddy bear Thanchai. And Thanchai? He’s a foul-mouthed wise guy who drinks whisky and also smokes.

Grandmas are reincarnated as geckos. The characters from a serial romance magazine step from the pages to knock on doors. And a mountain of plastic bottles dominates the Bangkok skyline, reaching clear to the moon.

Oh, and there's a taxi-cab passenger who has forgotten where he is going and compulsively licks everything with his tongue.

This is the world that Pod (punk-band guitarist Mahasamuth Boonyarak) lives in. He’s a country boy who moves to the city and takes a job in a sardine factory. One hot day, in a scene right out of Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times, the assembly line goes haywire and, in all the confusion, he chops his finger off and it ends up in a can on the shelf at the grocery store. He searches everyday, buying can after can of sardines. Eventually he sees a can jumping around and opens it to find a finger. He attaches it simply by pressing it into place.

But something doesn’t feel right. He must have someone else’s finger. During a lunch break, he recognises his own finger on a guy who’s getting ready to pick his nose. He wrests the finger away and gives the guy the other finger in return. The nose picker is named Yod (Sawasdiwong Palakawong na Ayudhaya), and the two become friends.

Not wishing to lose any more fingers, Pod quits the factory and becomes a security guard. On the job in an office, he meets Jin (fashion model Sangthong Ket-uthong), a maid who has her nose perpetually buried in a mysterious white book written in a foreign language that she dreams of someday understanding. She has an obsessive-compulsive disorder, which makes her want to constantly clean and set things in order. This is an admirable trait for a maid, but it doesn’t make her very popular with her co-workers.

Pod is smitten. He sees her face everywhere – in a light bulb, in a plate of fried rice, even in his Bruce Lee Game of Death movie poster. He wishes to be closer to Jin, like Yod and his unbelievable sexy Chinese empress girlfriend. Those two consummated their relationship on a crowded bus and have the tickets to prove it. Pod asks Jin if she would like to ride the bus. But Jin refuses, saying she breaks out in a rash whenever she takes crowded public transport. Pod quits his job as a guard and becomes a taxi driver so he can drive her to work. Bangkok’s red and blue taxicabs fit especially well with the set design, by the way.

Though she wears the same bright blue uniform everyday, Pod makes a point of telling her how beautiful the dress makes her look. She thinks he’s crazy. Maybe he is. From the fat cop directing traffic to the puppies in Pod’s dog’s litter, everyone is wearing the same blue dress.

Eventually, he expresses his true feelings for Jin, but by then she’s become obsessed with a hippie Westerner (Asian film critic and subtitlist Chuck Stephens) whom she believes is an environmental activist. She starts collecting plastic bottles, gathering enough to create a literal mountain, and joins an environmental protest rally.

On the surface, Citizen Dog is a romantic comedy, but really it’s a satire, poking fun at hectic urban life, cell-phone chatterers and kids hooked on video games and ignored by their parents. Wisit wants to comment on materialism and conformity. Something that reminded me of all the generaic products in Repo Man, the characters in Citizen Dog are given labels. Depending on his job, Pod’s uniform says “Factory”, “Security” or “Taxi”. Jin’s label is “Maid”. And Jin revels in the conformity of joining a crowd of protesters.

Both the lead actors are making their feature-film debut. Mahasamuth is a guitarist, singer and songwriter in a punk band called Saliva. Songtong is a fashion model with aspirations of making it big in the art world. Both are wonderful in this film, especially Songtong who reminds me a lot of Audrey Tautou or even a Steven Soderberg-directed Julia Roberts.

There's a dog motif that manifests itself in many ways. The sardine brand is called "Dog With Helmet". There is a concrete dog statue outside the office building where Pod works as a guard. Also, the company is called Good Boy Industries. Baby Mam's parents have a statue of a dalmation in their living room. Pod has a mother dog and a litter of puppies outside his home. And the name of the band that does the theme song (which is played over and over in many variations throughout the film) is Modern Dog.

From the zombie biker to the granny gecko to the talking teddy bear, there's a lot to take in. We're helped along the way by folksy narration from one of the other leading lights of Thai cinema, Pen-ek Ratanaruang.

But there' still some confusion. Somehow, Pod becomes a celebrity because he’s the only guy in Bangkok without a tail. His grandmother warned him he would grow a tail if he moved to the city. But somehow, he escapes that fate, and his hounded by reporters and packs of teens wanting to see his tailless derriere. If he does grow one, he’ll just be one of the crowd, the “citizen dog” alluded to in the title. The Thai title isMah Nakorn, translated as "Dogville", meaning Bangkok is a city of dogs. It’s a confusing, oblique concept because the tails that everyone supposedly has aren't ever seen. And this is despite tons of other photographic tricks. It detracts a bit from the overall enjoyment of the film. But that’s part of its appeal. It gives you something to think about long after you’ve left the cinema. There is a lot to enjoy in Citizen Dogand enough to make repeated viewing worthwhile. I hope it will be out on subtitled DVD and on the international circuit soon.

- thaifilmjournal.blogspot.com/

The Unseeable (2006)

In this smart, tangy neo-gothic ghost story, the Thai director Wisit Sasanatieng (“Tears of the Black Tiger”) cleverly recycles every cliché in the book and adds a sense of wonder all his own. Nualjan, a poor, pregnant country girl, wanders far from home in search of her missing husband, and, exhausted, stops at a lonely rural manor. There, Somjit, a tyrannical housemaid, grudgingly takes her in with a warning to stay far from the mistress of the house, Madame Ranjuan. But a glimpse of Ranjuan through a high window reveals her odd resemblance to Nualjan herself. And when the guest gives birth, Ranjuan takes an unusually strong interest in the newborn. To the film’s eerie apparitions and disappearances, an evil old crone, a vampire legend, secrets behind the door, and long-hidden crimes, Sasanatieng adds a rhapsodic romantic melodrama, as well as a compelling visual design that conjures up the all-seeing gaze of looming spectres. The result is an engaging, surprisingly heartfelt entertainment. In Thai. - RICHARD BRODY

The Unseeable is the first film by Wisit Sasanatieng that was not written by him, but by Kongkiat Khomsiri, a member of the Ronin Team (Art of the Devil 2). This fact takes some of the weight away from the fact that in 1999 Sasanatieng wrote the screenplay for one of the best ghost stories in recent Thai cinematic history, Nang Nak by Nonzee Nimibutr; however, a parallel can still be perceived between that film and The Unseeable, the first horror film from the director of Tears of the Black Tiger. A horror film made on a limited budget, but one that is sumptuous and convincing, which reprises the classic theme of the “haunted house” with ingenious extremism.

The accumulation of horrors, which at first seem like a collection of scattered thrills, in the end will come together to form a very coherent picture, full of that melodrama which the horror genre always contains.This passion for melodrama, this love for vintage settings as well as for the cinema of Rattana Pestonij (the “father of Thai cinema”, whose Country Hotel is cited in the bar scene), is pure Sasanatieng.

The Unseeable also pays homage to the atmosphere and graphic style of the Thai pulp illustrator Hem Vejakorn (1904-1969) - so much so, that the director came across some trouble with Vejakorn’s copyright holders.

It is the early 1930s. A pregnant Nualjan exhaustedly wanders around searching for her husband Chob, who has left “for a few days” never to be seen again. The sour housekeeper Miss Somjit allows her to stay in Madame Ranjuan's villa. The latter is a beautiful widow who lives as a recluse after the death of her husband. It is a house full of whispers and sighs, as well as unclear visions, amplified by a gloriously ominous music.

The accumulation of horrors, which at first seem like a collection of scattered thrills, in the end will come together to form a very coherent picture, full of that melodrama which the horror genre always contains.This passion for melodrama, this love for vintage settings as well as for the cinema of Rattana Pestonij (the “father of Thai cinema”, whose Country Hotel is cited in the bar scene), is pure Sasanatieng.

The Unseeable also pays homage to the atmosphere and graphic style of the Thai pulp illustrator Hem Vejakorn (1904-1969) - so much so, that the director came across some trouble with Vejakorn’s copyright holders.

It is the early 1930s. A pregnant Nualjan exhaustedly wanders around searching for her husband Chob, who has left “for a few days” never to be seen again. The sour housekeeper Miss Somjit allows her to stay in Madame Ranjuan's villa. The latter is a beautiful widow who lives as a recluse after the death of her husband. It is a house full of whispers and sighs, as well as unclear visions, amplified by a gloriously ominous music.

It is immediately obvious that we are in ghost territory (and of the gut-sucking vampire, who - like the krasue, recently seen in Yuthlert Sippapak’s Ghost of Valentine - loves to feed on the entrails of newborn babies). But who is the ghost? The unseeable world surrounds us; nothing is as it seems - not even the coarse maid Choy, a character that seemed destined to exhaust its role in the traditional function of comic relief.

The tale – which hides some unexpected moments of ribald humour – displays an excellent use of sound. When for Nualjan's benefit Choy provides a very funny parody of the typical horror tirade (“Ghosts do exist!”) just delivered by Miss Somjit, we hear her sardonically lugubrious voice, in voice-over, as the spectral child steps into the house, in a nice little short-circuit between the visual and the two meanings of sound.

Right from the vaguely unsettling play of editing in the opening on the street, cinematography and editing conspire to create an illusory and deceiving world, one subtly painful, made of ambiguous and evasive perceptions. One characteristic of this film is its reluctance to show the face of a character when it is first introduced: due to distance, to a delayed reversed angle, to transparent curtains like the ones that transform Madame’s bedroom into an impalpable, blurred labyrinth, to the choice of short shots or shots from behind... The most evident case is that of the husband, whose face we do not see, either early on in the flashbacks or later in the meeting in the pavilion: and this choice is not a necessary one for the unfolding of the story, for possible upcoming twists in the tale, but rather it is part of the “phantasmatic” strategy of the entire film.

The empty glance of a “living” camera wanders about the rooms and the garden; from above, it spies on the girl giving birth from an unreal angle; it creates unnatural subjective shots, like the leafy branches of the trees filmed from below when Nualjan goes to meet Madame. In the garden, when Miss Somjit tells Nualjan of the widow’s grief, a deceptive and bewitched travelling shot brings us from the flashback regarding Madame Ranjuan to the present day, without continuity – appropriately for a place where time turns around itself in sad loops.

The tale – which hides some unexpected moments of ribald humour – displays an excellent use of sound. When for Nualjan's benefit Choy provides a very funny parody of the typical horror tirade (“Ghosts do exist!”) just delivered by Miss Somjit, we hear her sardonically lugubrious voice, in voice-over, as the spectral child steps into the house, in a nice little short-circuit between the visual and the two meanings of sound.

Right from the vaguely unsettling play of editing in the opening on the street, cinematography and editing conspire to create an illusory and deceiving world, one subtly painful, made of ambiguous and evasive perceptions. One characteristic of this film is its reluctance to show the face of a character when it is first introduced: due to distance, to a delayed reversed angle, to transparent curtains like the ones that transform Madame’s bedroom into an impalpable, blurred labyrinth, to the choice of short shots or shots from behind... The most evident case is that of the husband, whose face we do not see, either early on in the flashbacks or later in the meeting in the pavilion: and this choice is not a necessary one for the unfolding of the story, for possible upcoming twists in the tale, but rather it is part of the “phantasmatic” strategy of the entire film.

The empty glance of a “living” camera wanders about the rooms and the garden; from above, it spies on the girl giving birth from an unreal angle; it creates unnatural subjective shots, like the leafy branches of the trees filmed from below when Nualjan goes to meet Madame. In the garden, when Miss Somjit tells Nualjan of the widow’s grief, a deceptive and bewitched travelling shot brings us from the flashback regarding Madame Ranjuan to the present day, without continuity – appropriately for a place where time turns around itself in sad loops.

Giorgio Placereani

The Red Eagle (2010)

The Red Eagle -- Film Review

"The Red Eagle."

Bottom Line: A vanilla, colorless remake of a legendary Thai superhero series.

BUSAN, South Korea -- Visual wizard and fantastical yarn-spinner Wisit Sasanatieng seems to be flying with clipped wings in directing "The Red Eagle," the anticipated remake-cum-homage to the 1960 Thai superhero action series "Isee Daeng." There is not a trace of the gloriously colorful retro camp of his debut "Tears of the Red Tiger" nor the flights of CGI fancy in his sophomore "Citizen Dog." Had Sasanatieng's name not been attached, the project may qualify as technically high-end Asian genre fare but marketing to his cinephile fans would turn converts into skeptics. Locally, "Insee Daeng"'s cult status would prompt Thais to see "Red Eagle" for old time's sake.

Corrupt politicians and gangsters are being brutally murdered by a mysterious killer known as Red Eagle (Ananda Everingham). Detective Chart and Sergeant Singh (Jonathan Hallman) are assigned to the case, all the while unaware that Chart's drunken loser friend Rome is the hero. Rome's love interest is Vasana (Yarunda Bunag), an NGO leader who opposes a nuclear project pushed by prime minster Direk, her ex-fiance.

The original "Insee Daeng" (Red Eagle) is a hybrid of Zorro and Batman. He is a lazy drunkard by day and a masked hero who fights crime with fancy weapons. The character was originally played by Mitr Chaibancha, a hot action star who fell to his death from a helicopter while performing a stunt for the final, 1970 edition "Insee Thong," 40 years ago this month.

The modern-day Red Eagle is a morphine addict, who, after a traumatic experience in the special forces, decapitates or mutilates villains with no qualms. The intention to mould Red Eagle as a dark hero with moral complexity like Christopher Nolan's "Batman" is obvious, but the characterization has gone too far to the dark side, making him rather unflattering.

The action is a melange of ancient swordplay, motorbike chases and leaps from high places. It looks good but choreography is not particularly creative, except for one street fight when Sergeant Singh improvises with satay sticks, woks and even sizzling spinach as his weapons.

Visual effects by Kantana are slick but art direction, all cold, metallic futuristic tones, offers a bland ambience. There isn't a shred of Thai character, not even any humor. If the project had been handed to Prachya Pinkaew and Panna Rittikrai ("Tom Yum Kung," "Chocolate") it would have tighter action and more cinematic panache.

With the legendary nature of the series and its cheesy 70s production values, there is a sorely missed opportunity for genre parody like "Iron Pussy" (co-directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Michael Shawanasee).

Not only does Red Eagle wear a mask, his nemesis Black Devil and members of Matulee, a secret association dedicated to Red Eagle's demise, all wear masks, making it hard to get involved with the story.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wisit_Sasanatieng

Wisit Sasanatieng's directorial debut, FAH TALAI JONE

(literally, The Heavens Strike the Thief), is a roller-coaster

ride across multiple genres, reinventing the Thai landscape and

Thai film at the same time. This East-meets-West,

oughties-cum-fifties feast, is the first thoroughly post-modern

Thai film. It features classic Thai comedy characters,

deliciously sincere leads, impossibly coy romance and acute

references to signal Thai films. It has been created with

theatrical wit and shot in the glorious bright colours of a

technicolour repast. It is a celebration of the Western, the

Romance and the Thai film canon. Packed with cowboys, soldiers,

bureaucrats and a fifties-style femme, her eyes brimming with

tears, the film make noodle soup of Spaghetti Western. Wisit's

tale of star-crossed romance between a hunted outlaw (the Black

Tiger) and his wealthy but unreachable beloved is a rollicking

good tale, filled with style, humour, gunplay, romance and

betrayal - - something like Zorro and Shane meet the Coen

Brothers in the Khorat Plateau. It's a romp. It's a ride. It's a

tip-of-the-hat to the past and a genre unto itself. It's a true

first

How did you come up with the title, Fah Talai Jone?

My impression of the old song, Fon Sang Fah (When the

Rain Bids the Sky Farewell), sung by Pensee Pumchusee, inspired

me. I do love those 'rain' songs. I've kept picturing a

beautiful frame of two guys shooting each other in the rain. And

that sparked it all! Initially, I chose Fon Sang Fah as the

title. But it sounds too much like a period piece (laugh)

Finally, we went for Fah Talai Jone (The Heavens Strike the

Thieves), for it can convey either a sense of obsoleteness or

the feel of great chic, depending on the film's context. In

fact, it's the name of a herbal plant. However, in terms of the

film it refers to predestination, in which most Thais believe.

To put it frankly, the main reason is simply because I like this

name.

Why in this style?

I think that Thai films are made to serve only Thais, not

counting those who are regarded as intellectuals. I'm happy to

make melodramatic films, which are, in fact, universal. All

top-flight films are melodramatic…like Gone with the Wind, which

is such pure melodrama, or Baan Sai Thong, which has never

ceased attracting people. In these commonplace films there must

be something that really clicks with the public.

It strikes me that most Thais see movies just as

something trivial, I don't say it's right or wrong. In fact,

it's kind of Thai nature. They just want to go adrift somewhere

for a couple of hours. Then when they get home, what's on the TV

screen is the same old fairy tale they've just seen at the

cinemas. It is all redundant. Like Nang Nak, for example, its

story is known by heart but people love to see it. It's their

source of happiness to see something expected. They think it's

charming. So do I.

How was the so-called "Fah Talai Jone" typical style initiated?

All started on the day I saw the film made by Raton

Pestonji at Chalerm Krung. Its negatives and color is filmed to

perfection. I found it stunning. But I can share this feeling

with no one because no one would believe me, not having seen the

way Thai films in the past were presented in such vivid colors.

This characteristic has become the style of Fah Talai Jone- -

-vivid colors, lighting and props. I only imitated Khun Raton's

style, not his plots. In fact, his plots are a lot more profound

than mine.

What makes Fah Talai Jone different is its conciseness.

Present-day audiences are not happy with the slow-paced films of

the old times. They would be put to sleep in no time. I also

added something new such as a view of a person in the distance

from between the legs of someone in the foreground. It's like I

made a good blend of various styles. For example, Sergio Leone's

cowboy films are labeled as "Spaghetti cowboys." Mine is " Tom

Yam Kung cowboys" because at one time cowboys were very popular

in Thai films as you can see in Mitr Chaibancha's films. My

'cowboy' imagination is also based on those figures in Por

Intharapalit's books. In Fah Talai Jone, the thieves' costumes

are not derived purely from my imagination. They are rather

idealistic thieves.

Action scenes like 'hill explosion' or 'hut on fire' were

also a popular style in Thai films in the past. Such scenes are

a stereotype of Thai film style. If this style were put into an

appropriate developmental process, it would have become a kind

of 'John Woo' films.

While shooting Fah Talai Jone, what kind of film did you think

it's going to be?

I tried to experiment. I've been told the 'style' is

unmarketable. It would work only as a 30-second ad. No one

believes it can work as a full-scale film. I don't argue. I just

want to prove my idea is right. Unless we attempt something new,

the style of period films will remain stagnant. Despite

considerable risks, I will take my chances.

Have you ever thought about audiences - - - whether they can

accept the film?

Yes, I have. I've discussed this with Oui (Nonzee) and

Eak (Fah Talai Jone's production designer). What worries me most

is whether or not the film will hold the audiences attention for

the first 10 minutes. If not, that's the end. Like Mars Attack!

and Ed Wood, for example, I have imitated the characteristics of

B-rated films in the past - - - a not too confusing plot and

very dominant style. We use the style as a bait to attract them

to the box office. When the audience is hooked and when they

find the story enjoyable, they may love the whole film. But I'm

not sure whether or not the style alone will be able attract the

audiences at the beginning (laugh).

This means you're quite confident of the story.

As far as I know, most people who've read the film's

script find it enjoyable. But this doesn't mean the story will

be as enjoyable as the script is to read. If the audience feels

about 80% of enjoyment the script readers felt, we will be

satisfied. Now it depends only on the promotional activities-how

to make people understand what we're doing.

If you didn't make Fah Talai Jone this way, you would not have

made it at all.

Certainly. Unless it was peppered with some modified

details or made in an extraordinary way, it would be just a

plain, familiar story.

In fact, the idea of playing with outdated stuff has been

booming for a long time.

As we can see in foreign advertisements, it's called the

'out-beats-in' style. If you have seen a commercial of Diesel

Jeans, Levis arch-rival , in Levis' s commercial, all the male

and female models are beautiful and are very chic. But Diesel's

commercial goes to the opposite extreme. The look of their

models is very, very obsolete. That creates a unique style. A

new chic style. Ironically, it's Levis' commercial that has

become obsolete.

I experimented in my Wrangler commercial, in which the

style of Thai films in the past was used. All was

obsolete---shooting, the model's posture and the model's face. I

had experimented with it before and I had found it attractive.

At that time, Oui was making Dang Bireley and the Young

Gangsters in which the same period style was used. That

interested my Wrangler account, so I asked him to sponsor the

film. Besides being a script writer, I am a salesman, too!

(laugh).

This causes the audiences to reminisce.

I'm not sure, because people are not interested in

cultures any more. Thanks to globalization, all countries are

the same throughout the world. Before the so-called 'millennium'

era, the 'space' films like Star Wars were very popular because

they contained hi-tech elements with which the modern world had

not caught up. But when it seems we've reached the peak of the

cutting age technology for the present, those 'space' films

don't interest us any more. It's films packed with reminiscence

like Ben-Hur or Gladiator that do.

You've said that Thai films once had a uniqueness, but it's gone

due to a lack of the developmental process.

That's my personal conclusion: All genres of Thai art

were beginning to flourish when a wave of foreign influences

crashed them all at once. Indeed, Thai art, especially the

architectural style, came under the European influences. But

these influential styles were harmoniously applied with our own

like wooden houses with the so-called "ginger-bread" decoration,

for example, and was developing into the Thai modern style. Then

this development was suddenly halted by those architects who

preferred colonial or Spanish styles. Likewise, the Suntharaporn

songs, the unique Thai pop style of music--although being

developed using western musical instruments - - were abruptly

replaced by rap music.

If that unique style of Thai films were fully developed, what

would it have looked like?

No way to know, because it doesn't exist. The only way to

know is to go back to the very transitional point where the

influence began, and start here. Now it is impossible to make a

Thai film in the "modern" style, because we don't know what it

is. It's been lost.

Will you continue with this very style in your later films?

Certainly. As you can see in the case of Chan Dara, we

had a lot of discussion about how the elements of our own

cultural way of production such as camera movement, angle of

view and character position could be applied without turning to

Western influences. The way actors were directed to stand in

line in older Thai films was disapproved of by critics who

preferred a Western over-the-shoulder angle of view. This rang a

bell with me. Our Likey [the Thai musical folk drama] characters

are also in a straight line position on stage. This may be our

cultural acting style which has been not applied or developed to

be our own "film language".

What would you think if the Fah Talai Jone style becomes a big

hit in terms of filmmaking?

Unsurprisingly, it should be so. The very fact that Japan

has its own style is only because everyone uses a common style.

Can you see the unique style shown in all Japanese films? Like

works of Takeshi 'Beat' Kitano, for example, stillness is

dominant in every frame. Even a cruel expression is conveyed

through its own way.

It would be perfect if every Thai filmmaker acted in

concert over this matter. Then our own style can be

cooperatively established. Today we rely too much on Western

graphic design. If we gradually replaced it with our own

uniqueness, which used to flourish in the past, one day we will

again have an individual style.

What about the post-production? I've heard that it was

meticulously done at every level.

In producing this film in the same style of vivid colors

as those films in the past, we, in addition to ordinary settings

and decorations, needed a color modifying technique called

"telecine" in the final stage. Through this technique, we can

simply turn the blue to green, which was the favorite color at

that time. In those days, the color of the skies in Thai films

was not just the usual 'blue' but rather turquoise which can be

acquired by means of the telecine technique. In addition, we

used the digital process of "D1" instead of an ordinarily

optical one, which has less special functions, to create and

modify all colors and special effects, even though a

time-consuming series of transfers between videotape and print

signals had to be carried out afterwards. . . .

What hard work!.

Yes. Since this film is not realistic; it's real fiction,

we had to set up every single thing. We found a location in

Pracheenburi that seemed perfect. It had a yellow-painted house

built in the reign of King Chulalongkorn, but when we got inside

it was not what we had envisioned. What we needed was BIG main

wooden stairs in a hall with a lead actress descending the

stairs. So we decided to set it up. We used up all our wood

supplies with the construction of the wooden stairs. Because of

our limited budget, we were compelled to shoot and finish all

scenes with the stairs before removing all wooden materials for

other settings like the sala, railway station and den of

thieves. However economical we tried to be, our original budget

was not sufficient because we had as many as seven locations. It

was all because of my greed! I just wanted the right scenes in

the right places, like, for example, trains in Karnchanaburi or

the water lily pond in Lopburi.

Did you design the acting, too?

Yes. I previously determined that all actors would act

without letting themselves be affected by the script itself.

Instead, I informed them before shooting of the exact facial

expression, feelings and actions they were required to portray.

This pre-determined acting technique follows acting methods both

in film and theatre industries in the good old days when

improvisation was unknown. At that time, even the angle of an

actress's face was measured for 45 seconds in the proper

lighting in order to acquire the so-called glamour shot which

creates an angle-like look.

Use of the same technique can also be seen in Japanese

films. For example, in those of Yasujiro Ozu. In one instance,

one of his actors was required to follow these steps: stare at a

cup of tea, count to ten, raise his hand to touch the cup, count

to three, bring the cup to that point…(laugh).

Likewise, Fah Talai Jone features such an acting

technique. It was my task to seek for only actors and actresses

who would potentially excel in this style. Stella is the best

example. We couldn't know how elegant and graceful a plain

Farang like her would become until she dressed up and wore

make-up.

web.archive.org/

Red Eagle is Wisit's farewell to the film industry

Fueled by huge expectations and fanboy anticipation, Wisit Sasanatieng's The Red Eagle (Insee Daeng, อินทรีเเดง) has become one of the year's most wildly hyped Thai movies, with huge billboards all around Bangkok and all kinds of other advertising, stunts and campaigns.

But will Red Eagle live up to the high-flying, CGI-assisted superhero hype?

That's the question that must be weighing heavily on Wisit as word has leaked out that he's leaving the film industry once Red Eagle is released on October 7.

News of Wisit's departure from the industry has apparently been whispered in the Thai media, and Twitch mentioned it on Twitter last week.

The Nation's Soopsip gossip column picked up on it today, citing a "mysterious source" that the director is "quite serious" about the move and that he has been "telling close friends and colleagues that he’s fed up making mainstream drivel for the studios."

Wisit confirms the news in a response to an e-mail:

I have decided to quit my director role and do something else instead.

I am too tired and don't want do studio feature films anymore.

But if someday I come back to direct a film again, that means I have found a story that I really want to tell, but in my own style and in the independent way, not with the studio.

Maybe I will do a comic book. That's something I've planned to do for a long, long time.

But actually, I have not made my decision on what I will do next.

After I've finished The Red Eagle, I just want to have a long break first.

Whatever Wisit ends up doing is going to be awesome. He's a vivid illustrator and imaginative writer, and a comic book will be very cool.

It could even lead him back to film, but only if, as Wisit says, he can do it his own way, in his inimitable style.

It's a style that was in full flower in his 2000 debut, the colorful 1950s-set westernTears of the Black Tiger (Fah Talai Jone, ฟ้าทะลายโจร), but hasn't really been seen since his second feature, 2005's fantasy romantic comedy-satire Citizen Dog(Mah Nakorn, หมานคร, except for perhaps his short film Norasingh Avatar, hisSawasdee Bangkok segment, Sightseeing, or maybe his many commercials and music videos. Wisit's 2006 feature, The Unseeable (Pen Choo Kub Pee, เปนชู้กับผี) did bear some of the hallmarks of his nostalgic outlook, with shoutouts to 1930s pulp-novel artist Hem Vejakorn, but seemed muted compared to his first two features.

Wisit's move to distance himself from the film industry echoes that of Tony Jaa, who has taken vows as a Buddhist monk and turned his back on a movie business he obviously felt betrayed him after budgetary constraints and creative differences led to his abandoning the set during the making of Ong-Bak 2 and offering a comparatively lackluster swansong with Ong-Bak 3.

The news of Wisit's departure from the business is also dampener to the excitement that has been building over The Red Eagle, a project that was announced to great fanfare nearly three years ago.

With Thailand's current superstar actor Ananda Everingham stepping into the role of a masked vigilante crimefighter, first portrayed by the legendary 1960s leading man Mitr Chaibancha – who died playing the part – Red Eagle studio Five Star Production obviously felt the movie was ripe for the hype.

But we shall see on October 7.

I have to admit, watching the English-subtitled trailer for The Red Eagle, I'm still pretty excited.

thaifilmjournal.blogspot.com/

.jpg)

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar