Afrofuturizam i kiborški humanizam.

nasher.duke.edu/mutu/art.php

The End of eating Everything

(detail), 2013. Animated video (color, sound), 8- minute loop, edition of 6. Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University presents artist Wangechi Mutu’s first animated video, created in collaboration with recording artist Santigold and co-released by MOCAtv on YouTube. The 8-minute video, The End of eating Everything,marks the journey of a flying, planet-like creature navigating a bleak skyscape. This “sick planet” creature is lost in a polluted atmosphere, without grounding or roots, led by hunger towards its own destruction. The animation’s audio, also created by Mutu, fuses industrial and organic sounds.

The video was commissioned by the Nasher Museum as part of Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey, the first survey in the United States for this internationally renowned, multidisciplinary artist, and her most comprehensive and innovative show yet. The End of eating Everything can be viewed in full in person at the Nasher Museum through July 21, 2013. - nasher.duke.edu/mutu/art.php

The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University presents artist Wangechi Mutu’s first animated video, created in collaboration with recording artist Santigold and co-released by MOCAtv on YouTube. The 8-minute video, The End of eating Everything,marks the journey of a flying, planet-like creature navigating a bleak skyscape. This “sick planet” creature is lost in a polluted atmosphere, without grounding or roots, led by hunger towards its own destruction. The animation’s audio, also created by Mutu, fuses industrial and organic sounds.

The video was commissioned by the Nasher Museum as part of Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey, the first survey in the United States for this internationally renowned, multidisciplinary artist, and her most comprehensive and innovative show yet. The End of eating Everything can be viewed in full in person at the Nasher Museum through July 21, 2013. - nasher.duke.edu/mutu/art.php

The Afrofuturism of Wangechi Mutu

Chiwoniso Kaitano

The last few years have seen the rise of a culturally significant type of creative. In literature, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Taiye Selasi, Teju Cole and many others have produced highly publicised and much-discussed complex narratives. In film and television, cross-cultural transplants feature in films and popular TV shows - Zimbabwean-American Danai Gurira and British-Nigerian Chiwetel Ejiofor come to mind. In contemporary art, diasporic Africans such as artists Chris Ofili, Julie Mehretu and Yinka Shonibare have found international acclaim.

The Tate Modern recently wrapped a major (and long overdue) exhibit of the modernist art of Sudanese-born Ibrahim El-Salahi, and earlier this year The Brooklyn Museum opened a floor to the awe-inspiring, house-sized pieces by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui in a widely viewed traveling exhibit. Also currently on exhibit at the museum is a survey of the work of Kenyan-American artist, Wangechi Mutu. This is an "Afropolitan" moment.

The Tate Modern recently wrapped a major (and long overdue) exhibit of the modernist art of Sudanese-born Ibrahim El-Salahi, and earlier this year The Brooklyn Museum opened a floor to the awe-inspiring, house-sized pieces by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui in a widely viewed traveling exhibit. Also currently on exhibit at the museum is a survey of the work of Kenyan-American artist, Wangechi Mutu. This is an "Afropolitan" moment.

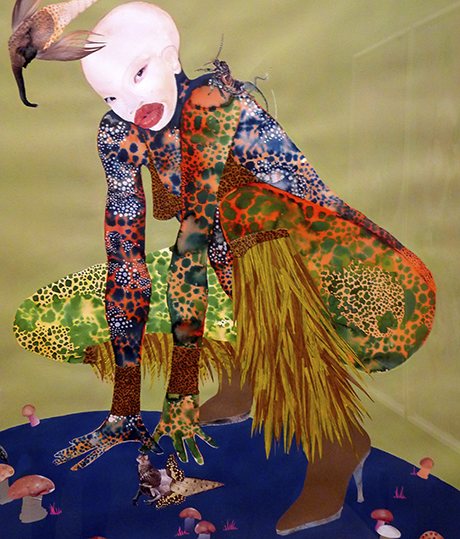

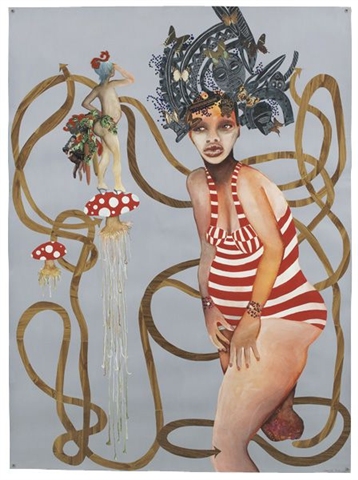

Detail from Riding Death in My Sleep. Courtesy: Chiwoniso Kaitano

Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey is a brief (50 pieces) but immersive exploration of the evolution of an artist. Although Mutu is a multimedia artist, she is perhaps best known for her large-scale, wildly colourful collages on Mylar. This thoughtfully presented survey includes presentations in a number of other media: video, site-specific fabric installations and, importantly, selections from the artist's sketchbooks dating back to 2005, the first time they have been on display. The exhibition rooms themselves are dimly lit with walls cast in soothing earth tones, a common curatorial choice which, in this case, effectively highlights the expansive energy of each piece.

There is no singular question at the core of Mutu's work. The collages themselves are complex, multi-layered, explosively hued pieces in which many themes are addressed simultaneously. This work is the ultimate existential mash-up. Mutu explores the complexities of this world by asking and answering a thousand questions at once.

A piece featured early in the survey is one that fully encapsulates the Mutu aesthetic. The themes with which she grapples in Riding Death in My Sleep are threaded throughout almost all of her work. A maybe-woman, alien-like in appearance, sits astride a globe. Her features are cross-racial, the skin is white. On top of her head is a winged and tailed fantastical elephant and to her side, an eagle head – the enduring symbol of the United States. The creature squats, poised as if to spring right out of the frame. At play are questions about multiculturalism, the sexualisation and objectification of the (black) female body, race, hybridity and all that it represents; conflict, isolation and "otherness".

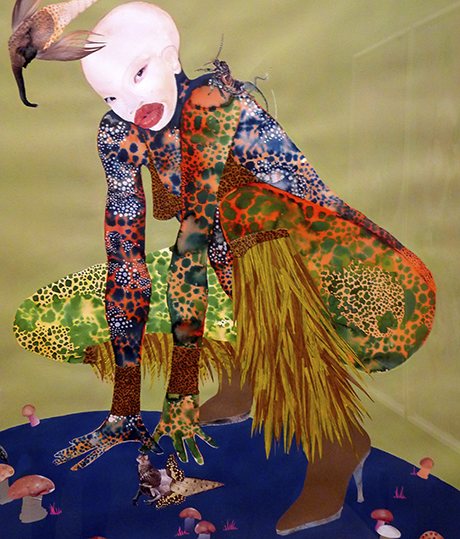

A Shady Promise. Courtesy: Chiwoniso Kaitano

At this point, Mutu has spent more time outside of Kenya than years spent there. Yet by her own admission, the imprint of her home continent is unmistakable. Representations of the art of the Makonde find a home in many of her pieces, as do birds in varying form – explained by the artist during a recent public presentation as the Kikuyu symbol of the spirit.

Suspended Playtime, a piece that occupies a central space in this curation, is a collection of balls made out of black plastic bound in twine and suspended with gold thread from the ceiling. This piece is intentionally reminiscent of the improvised soccer balls that children in cities and rural towns across Africa create and play with – a commentary on the resourcefulness of the children but also on lives often lived in comparative deprivation. Similarly, the rough grey fabric that clings to the walls like a fungus in a number of the installations is identifiable to a familiarised eye as the blanket fabric used in some township homes, dormitories and even prisons across southern Africa during cooler months. It's cheap, plentiful and these days probably made in China.

Mutu's use of specific and intentional imagery and symbols can be fairly easily contextualised, making her art essentially, accessible. In Your Story, My Curse, one of the central figures' rear end is partially covered by bananas and banana peels suggesting quite plainly Josephine Baker, arguably the first publically eroticised black female body in western culture who (in)famously performed in a banana skirt as part of her repertoire.

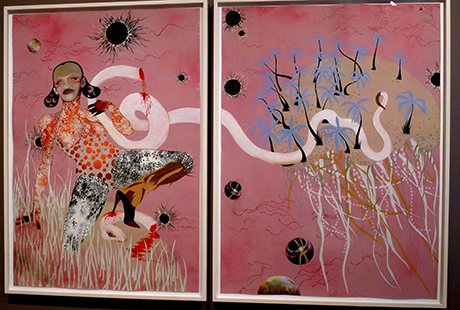

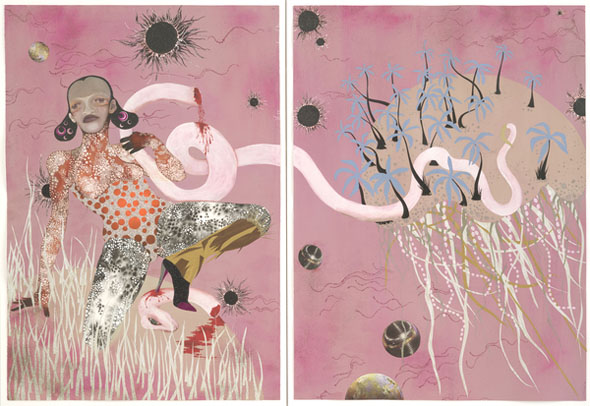

Yo Mama (2003). Courtesy: Chiwoniso Kaitano

Over the years, Mutu has repeatedly addressed the same themes, yet her work is far from stagnant. While earlier pieces such as Yo Mama (2003), an easily digested tribute to Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, mother of Fela, may lack the intensity and complexity of her newer work, standing alone it is tremendous. In this diptych, a wide-legged Eve triumphantly slings a headless snake across her shoulder while her stiletto boot drives down into the earth pinning down the snakes' head. The newer pieces may have more flash and glory and the earlier work may be sparer and plainer, but it's almost as though the artist knew she would have many opportunities to make her point. Hers is a talent that has been nurtured and allowed to cook slowly on the backburner, producing a rich, unctuous and sustaining broth.

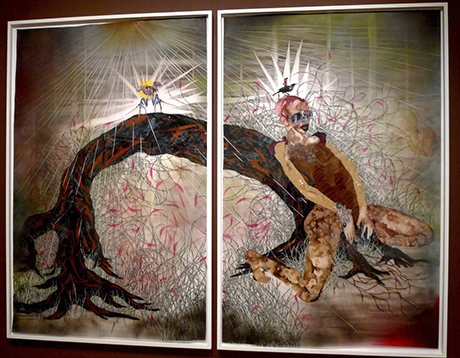

The Woods. Courtesy: Chiwoniso Kaitano

In stark contrast to the collages is the video. In Eat Cake, a 12-minute loop in which the main character is played by the artist dressed in elaborate gothic garb, Mutu creates something akin to a horror movie. A wild creature, with talons for nails and unkempt hair squats over a cake as though defecating and proceeds to destroy it. Something in this piece feels borrowed, but from what? A "witch doctor" or medicine man "bringing the bones" and speaking the language of the spirits he calls forth? It's terrifying but mesmerising stuff.

In a specifically commissioned collaborative animated film, The End of Eating Everything, boundary-bending musician Santigold portrays a medusa-haired creature with an insatiable appetite. This piece places itself firmly in the emergent so-called genre Afrofuturism – a label that attempts to categorise similarly minded genre-flexible art which might include anyone from musicians Janelle Monae and Sun Ra to filmmaker and fellow Kenyan Wanuri Kahiu, whose short film, Pumzi, created a stir at Sundance a few years ago. In Afrofuturism the black experience is re-examined, often with alternate endings. Science fiction allows Africans and those of African descent to grapple with the painful legacies of the racialised past. Mutu's work will be included in an exploration of Afro-futurist art, opening soon at the Studio Museum of Harlem in New York.

While this survey is comprehensive, a more complete viewing of Mutu's work would have to include more of the artists' extraordinary non-collage pieces. Two notable works, Exhuming Gluttony: Another Requiem, an installation in which wine bottles drip onto a huge wooden table in a room lined with animal pelts and the Blackthrones series – an assemblage of towering black chairs, are not included. Still, based on the vast and extraordinary body of work that Mutu has produced over the last decade, the well from which her inspiration springs, is deep. Undoubtedly, she has much more to show us.

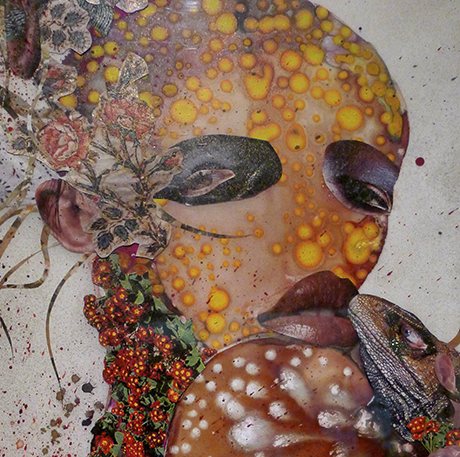

Detail from Lizard Love. Courtesy: Chiwoniso Kaitano Chiwoniso Kaitano

Kenyan-born Wangechi Mutu has trained as both a sculptor and anthropologist. Her work explores the contradictions of female and cultural identity and makes reference to colonial history, contemporary African politics and the international fashion industry. Drawing from the aesthetics of traditional crafts, science fiction and funkadelia, Mutu’s works document the contemporary myth making of endangered cultural heritage.

Piecing together magazine imagery with painted surfaces and found materials, Mutu’s elaborate collages mimic amputation, transplant operations and bionic prosthetics. Her figures become satirical mutilations. Their forms are grotesquely marred through perverse modification, echoing the atrocities of war or self-inflicted improvements of plastic surgery. Mutu examines how ideology is very much tied to corporeal form. She cites a European preference to physique that has been inflicted on and adapted by Africans, resulting in both social hierarchy and genocide.

Mutu’s figures are equally repulsive and attractive. From corruption and violence, Mutu creates a glamorous beauty. Her figures are empowered by their survivalist adaptation to atrocity, immunised and ‘improved’ by horror and victimisation. Their exaggerated features are appropriated from lifestyle magazines and constructed from festive materials such as fairy dust and fun fur. Mutu uses materials which refer to African identity and political strife: dazzling black glitter symbolises western desire which simultaneously alludes to the illegal diamond trade and its terrible consequences. Her work embodies a notion of identity crisis, where origin and ownership of cultural signifiers becomes an unsettling and dubious terrain.

Mutu’s collages seem both ancient and futuristic. Her figures aspire to a super-race, by-products of an imposed evolution. In this series of work, she uses old medical diagrams, to convey the authenticity of artifact, as well as an appointed cultural value. Satirically identifying her ‘diseases’ as a sub/post-human monsters, she invents an equally primitive and prophetically alien species; a visionary futurism inclusive of cultural difference and self-determination. (bio)- www.escapeintolife.com/

Wangechi Mutu at the Saatchi Gallery

Wangechi Mutu on Artnet

Cyborg Humanism: Wangechi Mutu at Brooklyn Museum

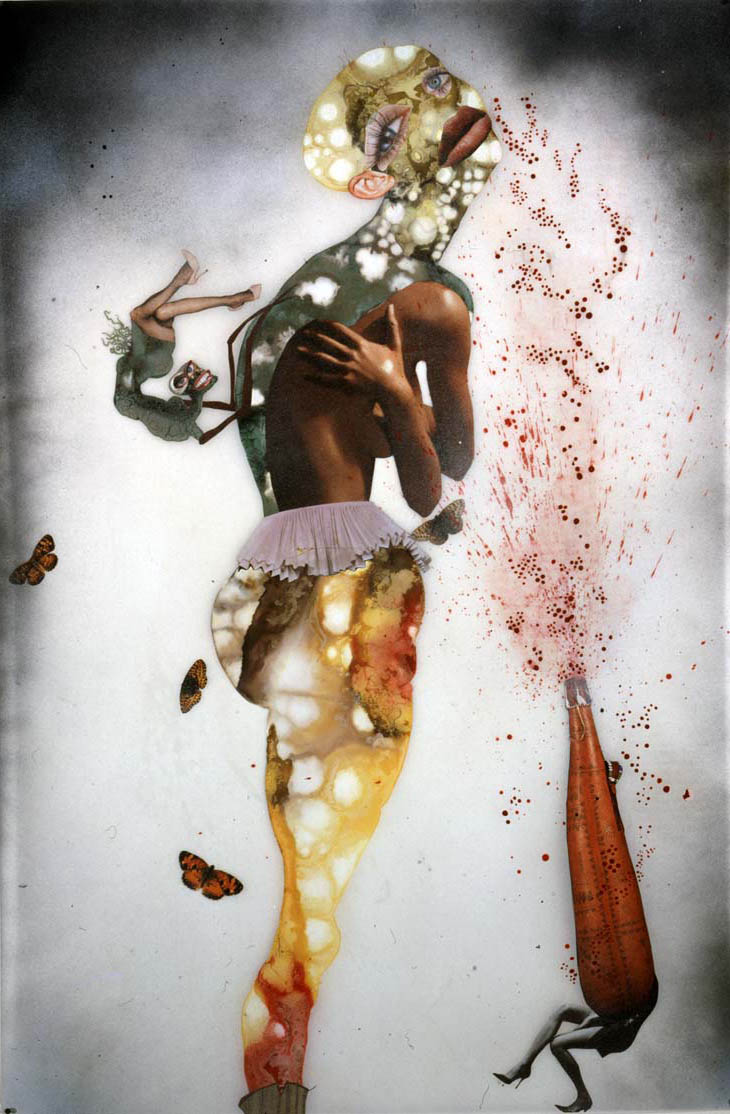

Wangechi Mutu, A'gave you (2008). Mixed media collage on mylar, 93" x 54".

The violent and ambiguous encounter depicted in A'gave you (2008)

encapsulates the force and intent of Wangechi Mutu's collages, the

highlight of her ongoing retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. A blue,

thick-rooted, and out-sized version of the New World monocot bends to a

violated female pseudo-cyborg. Her eyes, cheap black speckled pearls,

are replicated in the plant's ovary. The kneeling figure's torso, head,

and left arm are thrown back in disinterested submission; her right arm

is lost to perspective and/or trauma. Gold sparkle and blood explodes

from her chest as she births, or pisses, a long, fat strand of bright

yellow-orange which forms a new root-system beneath both her and the

plant.Mutu's strangely lucid mixed-media mylar pieces contort the sexualization of black women in consumer society into glittering, gorgeous grotesques. The twin pieces 100 Lavish Months of Bushwhack (2004) and Misguided Little Unforgivable Hierarchies (2005) feature female figures hobbled with hippo hands, faces stitched together from pornographic images, golden skin, and exploding motorcycle high-heels. They also depict differing levels of power among multiple exploited figures. The End of Eating Everything (2013), Mutu's first foray into animation, features the head of Santigold gnashing a gyring flock of black birds with bloody chompers. Slowly, the plane Santigold exists on expands to reveal that her face leads a massive she-planetoid, comprising writhing limbs and embedded, useless machinery, powered by her/its own gaseous effluent. The piece is truly disconcerting and accentuates Mutu's often overlooked theme of ecological disaster.

Wangechi Mutu, The End of Eating Everything (2013).

Mutu's sketchbooks, some of which stretch back as far as her

undergrad years at Cooper Union, are also on view; one of the displayed

pages reads: "in Your mind you envision Yourself a butterfly But you

still find yourself on your knees." Her figures, assembled

commodifications only human enough to be complicit in their own

subjugation, could be seen as an expansion of this phrase: spiky hope

born of spangly misery. Sometimes this is made too obvious. Yo Mama

(2003) is a kind of non-portrait of Nigerian politician and

human-rights activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti vanquishing a serpent. This

Mutuization of the political/social mural has little of the impact of

her less triumphal pieces.

Wangechi Mutu, Yo Mama

(2003) Ink, mica flakes, pressure-sensitive synthetic polymer sheeting,

cut-and-pasted printed paper, painted paper, and synthetic polymer

paint on paper. 59 1/8 x 85 inches

In a 2010 interview with Daily Serving, Mutu

stated she attempts to use "the aesthetic of rejection, or poverty, or

wretchedness as a tool to talk about things that are transcendent or

hopeful..." The encounter depicted in A'gave you is both

transcendent and non-consensual, and the plant's intentions are inhuman,

unknown. The warrened figure can still bring forth the new, strange,

and beautiful, but only through further violence against the self. The curatorial text accompanying A'gave you connects Mutu's work to Afrofuturism, "an aesthetic that uses the imaginative strategies of science fiction to envision alternate realities for Africa and people of African descent." When looking at a work like Mutu's A'gave you with this concept in mind, the implication is that the strange and violent birthing process she depicts suggests a new type of life, a radically different and therefore potentially liberated future. But in addition to opening up such readings, thinking about Mutu in relation to Afrofuturism also helps to situate the work in relation to other practitioners.

The term "Afrofuturism" was coined by Mark Dery in his 1992 essay "Black to the Future," which asked why so few African-Americans have created SF when they are "in a very real sense, the descendants of alien abductees," whose bodies are all too often impacted by the tech of "branding, forced sterilization, the Tuskegee experiment, or tasers." Dery posed the question, "Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?" Dery's 1992 answer was that one had to look outside the fiercely protected boundaries of the SF genre to find examples of this. Within SF proper, Afrofuturism's scope was, until recently, limited to a small number of practitioners. Dery could only name four African-American SF authors, including Octavia E. Butler and Samuel R. Delany, whose 1998 essay "Racism and Science Fiction" enumerates still relevant intra-genre problems. But examples of Afrofuturism can be found in disparate snatches from literature, popular music, and visual art: Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, Romare Bearden's collage work, the "pie-eyed, snaggletoothed robot" in Jean-Michel Basquiat's painting Molasses, and the various output of Jimi Hendrix, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and Herbie Hancock.

Over the past two decades, Afrofuturist discourse has expanded, and Ytasha L. Womack, author of this year's primer Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, has a much broader and deeper field to draw from. Authors such as Nnedi Okorafor and N. K. Jemisin explicitly write SF. Womack places Octavia E. Butler as one of the sides of her "Giza-like pyramid" of Afrofuturism, emphasizing her "central feminine narratives" as integral. DJ Spooky, Erykah Badu, and Grace Jones are amongst the plethora of cited musicians. A self-conscious and passionate fanbase has developed via Listservs, cosplay, and sites such as BlackScienceFiction.com. Womack posits contemporary Afrofuturism as challenging the nature of black art as only "washed in fatalism, southern edicts, or urbanized reality." Instead, Afrofuturism "inverts reality," offering a myriad of wormholes into alternate histories through which futures unbounded by trauma can be realized.

Kara Walker, Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching (2006). Painted laser-cut steel.

Just outside the entrance to the retrospective is a small pice by Kara Walker, Burning African Village Play Set with Big House and Lynching (2006).

Black steel silhouettes in the style of Victorian paper panoramas

assemble a confusion of violence and rape; even the setting, Africa or

the antebellum South, is uncertain. Walker's method of heightening

historical atrocity creates what Hari Kunzru recently referred to as an "endless carnival of cruelty that seems to be taking place in a sort of cultural Never-Neverland, somewhere between Gone With The Wind and

hell." Walker and Mutu both produce ravaged, if dissimilar, figures.

The latter's bodies have been invaded and taken over by color and

texture, the former's utterly reduced to black shadow; all have been

hyper-sexualized, though Walker's slaves have engorged genitals, not

motorcycle feet.Walker's statement that "a black subject in the present tense is a container for specific pathologies from the past" shows her intent: not to satirize slavery, but to focus only on the racist theories and caricatures invented to justify it, without offering any exit narrative. Womack mentions Walker only once in Afrofuturism, focusing on the "infamous nature" of her "harshly criticized work." It would be a misrepresentation to say Womack disapproves of Walker's approach, but it is certainly not the optimistic, transformative work which Womack wishes to emphasize. Mutu, who strangely goes without mention in Womack's book, exists somewhere between these two polarities. Her depictions of suffering and domination are subverted by the violent ecstasy of their imagining and her gestures toward alternate, unknown modes of life.

Science fiction necessarily speaks to the time of its creation, the author interpreting through distortion. This is exactly what Mutu accomplishes: her grotesques are our present. rhizome.org/

http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/wangechi_mutu.htm

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar