Rafman 2:

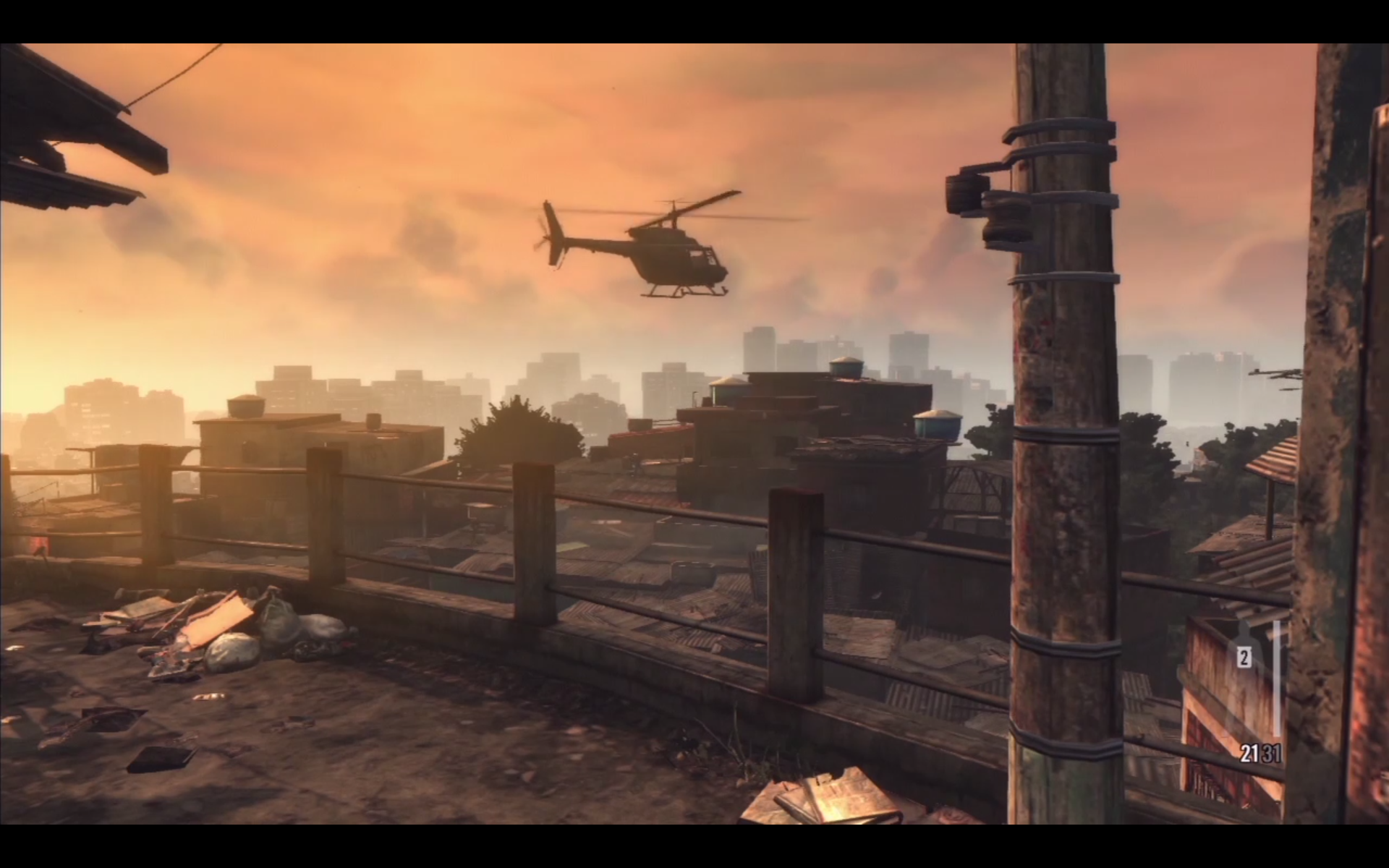

Izvrstan video sačinjen od "meditataivnih" (ne-akcijskih) dijelova kompjutorske igre Max Payne 3 do kojih možeš doći tek nakon što pobiješ sve likove jer te pravila igre stalno tjeraju da povezuješ narativne točke, koje te zapravo ne moraju zanimati.

A tu su i referencije na prirodu sjećanja, Benjamina itd.

Rafman je izvrstan net-artist.

jonrafman.com/

Jon Rafman premieres his newest film, A Man Digging, in which a narrator undertakes an evocative journey through a nostalgic wasteland. He is caught between past and present, between history, narrative and fiction, as he roams through the uncanny spaces of a video game massacre, frozen in time. The narrator’s monologue generates an erotics of memory as the simultaneously banal and spectacular scenes placed before the viewer meet his heady desire, and the film betrays an ontological rupture cloaked in the language of Benjaminian reflection. - the-maldives-exodus-caravan-show.com/

In Jon Rafman’s newest film, A Man Digging, a virtual flaneur undertakes an evocative journey through the uncanny spaces of video game massacres. In a re-visioning of the game Max Payne 3, Rafman radically transforms the role of the player. He now encounters the digital landscapes not as a numb fighter, but as a human who is touched by death and gore, even when it is rendered banal in its ubiquity. Divorced from their original context, the slaughtered bodies take on a dull, inarticulate violence that is disquieting. Through a film that becomes a de-sensationalized spectacle, Rafman confronts both the danger of passively aestheticizing the wreckage of the past, and the romantic fixation on death as a placeholder for meaning.

This video is Rafman’s latest contribution to his ongoing series that interrogates the nature of memory. As the narrator drifts through nostalgic recollections of his fragmented past, Rafman takes us through the gleaming surfaces of memory to the far edge of the real. - dismagazine.com/

In A Man Digging, Jon Rafman engages with the emotional and perceptual experience of a present-day explorer as he navigates virtual worlds. The contingency and intrinsic mutability of memory are foregrounded in the exhibition as Rafman explores the distance between our online and offline experience. Incorporating both anachronistic and cutting-edge technologies, commissions from deviantart.com, and footage from video games, A Man Digging shows how virtual worlds have dislocated the archive from its traditional moorings and given rise to new forms of desire, anxiety, and nostalgia. While examining Rafman’s ongoing preoccupation with loss, the work directs our attention toward the potential of the virtual archive to unveil alternative ways of constructing and preserving our collective and personal histories.- www.seventeengallery.com/

A Man Digging, Press Release

Spatial metaphors have been used to explain and visualise internet processes since the technology's earliest incarnations in the 1960s. Ranging from the banal (site; portal; window; archive) to the once-futuristic, now hackneyed (digital frontier; information superhighway; cyberspace), these metaphors are now entrenched in the popular consciousness. Yet the naturalisation of these terms obscures their function as ideological constructs that helped shape the development of internet technologies, by defining their surrounding discourse, projected uses and power dynamics.

Jon Rafman draws forth the constructed nature of spatial metaphors by re-applying notions of the frontier, highway, landscape and archive to online content and systems in literal or uncanny ways. Like any dedicated cyberflâneur, Rafman rejects the familiar information pathways generated by applications and search engine shortcuts. He is interested in modes of mapping, but not direct routes or predetermined destinations. The internet developed (and continues to develop) without guidelines: not exactly organically, but erratically and unevenly. Rafman's works mirrors this growth, privileging the search over the result.

'A Man Digging' brings together several components of Rafman's recent practice, including a print and bust from the series 'New Age Demanded'; several moving image works; a reworking of ongoing photographic series 'The Nine Eyes of Google Street View' as a microfiche archive; and a selection of works entitled 'Annals of Time Lost' in which online-sourced imagery is overlaid onto display media, including a blueprint hanger, a canvas, and a flatscreen television. This latter work contrasts an abundance of visual content—today's online experience is still largely optical—with linear schematics of virtual reality equipment that recall science fiction's promises of full sensory engagement: cyberspace in real space. Rafman juxtaposes the enthusiasm of mid-1990s net art with the sense of banality and lost opportunity that dampens contemporary attitudes towards the internet.

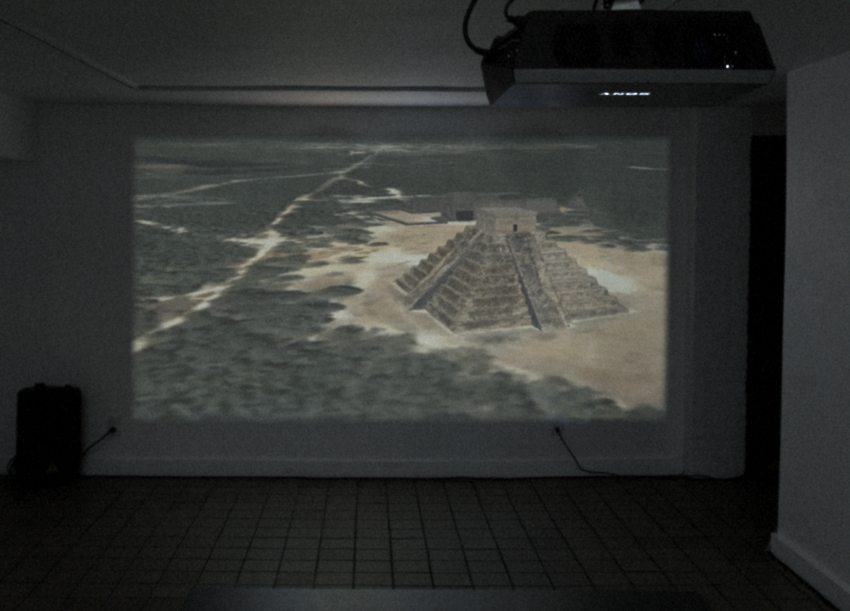

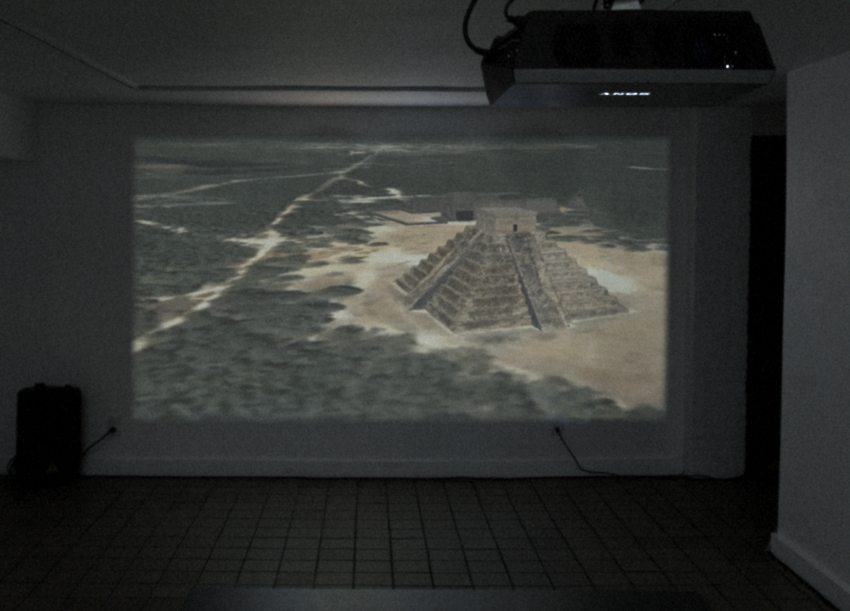

In 'Remember Carthage' and 'A Man Digging', Rafman reanimates the notion of the Internet Explorer by launching expeditions into desolate, digitally-rendered landscapes compiled from video game footage. The foregrounding of background content is unsettling: the scenery is visually rich but lacking focus, and therefore hard to remember. The narration—ruminations on the nature of reality, fragmented time, and the difficulties of becoming truly lost—and slow, panning movement of the clips are hypnotic, capturing one's attention with an endless flow of imagery but without the pauses or varied pacing that allow it to be processed. The internet itself also possesses this glut of non-hierarchical data. Different forms of cognition are required to cope in the virtual world: as memory is outsourced and uploaded, the relevance of remembering information is replaced with the need to know where information is stored and how to access it.

Rafmans's digital digressions are not social exercises, though they do reference channels of online communication and content sharing, and the communal memories formed during video gaming. Instead, Rafman reasserts the validity of individual experience and the importance of personal decision-making at a time increasingly characterised by frictionless sharing, big data analysis and the social networking mantra that life is automatically richer as a collective experience.Marianne Templeton

Flitting from one image to another, between different fragments of

information and imagery, the experience of Jon Rafman’s exhibition at

Seventeen was somehow analogous to our everyday use of the Internet. The

films and other works presented in ‘A Man Digging’ plunge into

different histories and roam around virtual worlds, shifting from

quasi-anachronistic to cutting-edge technologies, from a tactile

experience to a perusal of flat-screen monitors. Rafman’s imperfect

digital worlds encapsulate violence, destruction and melancholy, yet

also seductiveness and beauty.

The Montreal-based artist has been producing videos for ten years,

but employing the techniques of video-games and the online virtual world

Second Life for making these works is a recent departure.

Rafman does this by actually playing a video-game that is simultaneously

recorded; he later edits it, adding sound and a voice-over. In the

resulting works, these virtual platforms are an encounter between

romanticism and artificiality – even moments of rapt contemplation

become disturbing.

In the Realms of Gold (2012) opens with a pastoral

landscape, which is rudely interrupted by the sudden appearance of a

camouflaged soldier. He seems to lack autonomy, unable to exit this

rural environment. This inability to escape the ‘real world’ is also

evident in the 14-minute Remember Carthage (2012–13), in which

the narrator travels back in time, trying to locate an uninhabited

‘resort’ in the Sahara desert. His journey remains unresolved. An

uncanny feeling is instilled by the narrator’s descriptions: he seems

somehow familiar with these places, such as a Tunisian marketplace, even

though he has never visited them before. Unlike the video-games – with

their fulfillment of desires and multiple choices – that provide the

sources for these works, in Rafman’s films there is no possibility of

autonomy. Real and virtual worlds collapse in on each other, until one

comes to seem much like the other.

Rafman sees himself as an artist-archivist, attempting to contribute

to the cataloguing of history: ‘Framing my own experiences to create my

own archive that is aesthetic […] but not necessarily rational.’ This

recalls Mark Leckey’s influential performance-lecture Mark Leckey in the Long Tail

(2009), which traced the recent history of communication technologies

while trying to locate the tangibility of digital information storage on

the Internet. Leckey came full circle by returning to two towers of

computers, implying that we always seek material form – however outmoded

– for information.

Rafman’s subversive archiving gestures are present in two new works, Nine Eyes of Google Street View Microfiche Archive and Annals of Time Lost Microfiche Archive

(both 2013), in which he has transferred images from Google Street View

onto quasi-obsolete microfiche readers. These works evolved from an

earlier project based upon enlarged Google Street View images. Another

archiving gesture employs schematic drawings from online artist

communities layered over fragmented digital images of paintings taken

from The National Gallery’s collection, printed on chiffon and presented

on an architectural blueprint display rack. As with the microfiche

readers, Rafman here seeks to set aside the dichotomy between

technologies, displaying the latest technology hung on a classic method

of archival storage.

These pieces reflect Rafman’s aim, which he has described as ‘to

eliminate the dichotomy between technologies’. Critical of real and

virtual worlds, the artist sees both as limited and deterministic.

Whether heavily programmed or controlled by socio-political structures,

for Rafman neither world offers greater freedom. By including historical

references in his virtual works, he always emphasizes the ‘real world’

origins of digital products. He also raises awareness about the

continuous change in how we view, perceive and store images due to

technological change. Rafman’s traversing of online and offline

platforms allows him to intervene in the past, but also the future. His

attempt to archive digital content might be, however, ultimately

Sisyphean. - Galit Mana www.frieze.com

Flitting from one image to another, between different fragments of information and imagery, the experience of Jon Rafman’s exhibition at Seventeen was somehow analogous to our everyday use of the Internet. The films and other works presented in ‘A Man Digging’ plunge into different histories and roam around virtual worlds, shifting from quasi-anachronistic to cutting-edge technologies, from a tactile experience to a perusal of flat-screen monitors. Rafman’s imperfect digital worlds encapsulate violence, destruction and melancholy, yet also seductiveness and beauty.

The Montreal-based artist has been producing videos for ten years, but employing the techniques of video-games and the online virtual world Second Life for making these works is a recent departure. Rafman does this by actually playing a video-game that is simultaneously recorded; he later edits it, adding sound and a voice-over. In the resulting works, these virtual platforms are an encounter between romanticism and artificiality – even moments of rapt contemplation become disturbing.

In the Realms of Gold (2012) opens with a pastoral landscape, which is rudely interrupted by the sudden appearance of a camouflaged soldier. He seems to lack autonomy, unable to exit this rural environment. This inability to escape the ‘real world’ is also evident in the 14-minute Remember Carthage (2012–13), in which the narrator travels back in time, trying to locate an uninhabited ‘resort’ in the Sahara desert. His journey remains unresolved. An uncanny feeling is instilled by the narrator’s descriptions: he seems somehow familiar with these places, such as a Tunisian marketplace, even though he has never visited them before. Unlike the video-games – with their fulfillment of desires and multiple choices – that provide the sources for these works, in Rafman’s films there is no possibility of autonomy. Real and virtual worlds collapse in on each other, until one comes to seem much like the other.

Rafman sees himself as an artist-archivist, attempting to contribute to the cataloguing of history: ‘Framing my own experiences to create my own archive that is aesthetic […] but not necessarily rational.’ This recalls Mark Leckey’s influential performance-lecture Mark Leckey in the Long Tail (2009), which traced the recent history of communication technologies while trying to locate the tangibility of digital information storage on the Internet. Leckey came full circle by returning to two towers of computers, implying that we always seek material form – however outmoded – for information.

Rafman’s subversive archiving gestures are present in two new works, Nine Eyes of Google Street View Microfiche Archive and Annals of Time Lost Microfiche Archive (both 2013), in which he has transferred images from Google Street View onto quasi-obsolete microfiche readers. These works evolved from an earlier project based upon enlarged Google Street View images. Another archiving gesture employs schematic drawings from online artist communities layered over fragmented digital images of paintings taken from The National Gallery’s collection, printed on chiffon and presented on an architectural blueprint display rack. As with the microfiche readers, Rafman here seeks to set aside the dichotomy between technologies, displaying the latest technology hung on a classic method of archival storage.

These pieces reflect Rafman’s aim, which he has described as ‘to eliminate the dichotomy between technologies’. Critical of real and virtual worlds, the artist sees both as limited and deterministic. Whether heavily programmed or controlled by socio-political structures, for Rafman neither world offers greater freedom. By including historical references in his virtual works, he always emphasizes the ‘real world’ origins of digital products. He also raises awareness about the continuous change in how we view, perceive and store images due to technological change. Rafman’s traversing of online and offline platforms allows him to intervene in the past, but also the future. His attempt to archive digital content might be, however, ultimately Sisyphean. - Galit Mana www.frieze.com

Lingering Patience

Nicholas O'Brien

Jon Rafman, A Man Digging (2013), Single channel HD video

Jon Rafman uses the intricate tableaux of Rockstar Games' Max Payne 3 as cinematic source material for his new machinima work, A Man Digging

(2013). In this meandering and Robbe-Grillet inflected narrative,

Rafman ruminates on the simulated sunbeams glinting through favela

windows within the game, a melancholy sunrise in a deserted subway car, a

heavy fog over a slate grey harbor. He can only do so, however, after

killing every character—whether enemy or bystander—in the scene. In this

way, Rafman makes visible the tension between the game as object of

contemplation and the game as a continuous stream of connected events.Nicholas O'Brien

Jon Rafman, A Man Digging (2013), Single channel HD video

Although many makers outside of the industry have used video games as source material—Peggy Ahwesh, JODI, Eva and Franco Mattes, and Phil Solomon, to name a few—A Man Digging highlights a particularly frustrating issue in contemporary game design: namely, a pushy Artificial Intelligence system that goads the player into constantly responding to the checkpoints, achievements, and goals that are all in the service of what tends to be called a game's "narrative." Although these events don't necessarily develop plot or characters, they are seen as central components of driving (or forcing) the player toward a sense of completion and finality that can only be accomplished through linear gameplay. As a result of this insistent narrative-centric design, players are prevented from exploring the potential for triple-A games to take on the unique, interactive potential to create contemplative and self-reflective video game environments.

When playing Rockstar Games' Red Dead: Redemption, for example, I was always bothered by the way the game would interrupt me. Atop my horse, I’d want to admire the stunning vistas of the simulated Southwest and watch the cotton-tuft clouds hovering above big-sky country. The designers—or at least some of them—clearly wanted me to gaze upon this virtual splendor, just as one would meditate on a painting by Thomas Moran or Albert Bierstadt. However, the game’s AI would continually interfere, summoning cougars or coyotes, escaped convicts or roadside bandits, to ruin my perfectly good respite. Perhaps this was also some historical accuracy intended by the designers of RD:R, subtly educating players that the West in 1911 was still teeming with chaos. In other words, if you sat still for too long, you’d get eaten alive.

But the same style of “pushy” AI can also be found in Bethesda Studio’s Skyrim. Beneath every moonlit aurora borealis that shimmers across a creek bed lurks a malevolent frost dragon. In such a situation, a player can never become just an ordinary spectator, focusing attention on the game as a perceptual challenge and an aesthetic experience, but instead must always play the hero. In these moments, games abruptly breaks the focus on their immersive graphics in order to insist that the player take action. The environment is presented only for the sake of distracted consumption, not for contemplation. Instead of rewarding a player for becoming invested in the beauty of the game environment, games punish the player if they deviate from the primary goal at hand.

Irrational Games, Bioshock: Infinite (2013)

Rafman’s piece does not explicitly address

the need to undermine narrative, but it does suggest that games could be

built to accommodate a more contemplative player. To date, games

typically only reward a player’s focused attention on their environment

through cleverly placed “easter eggs” or some kind of “achievement.” In Bioshock: Infinite,

for instance, a curious player deviating from marked checkpoints will

be rewarded with brief vignettes. These cut scenes sometimes offer up

narrative information, such as the receipt of a telegram containing

instructions for the game's character, but they are at their most

captivating when they simply allow the moments of respite and aesthetic

contemplation, offering insight into the overall patina of a game world.This being said, some artists and developers have designed games that revolve around fleeting moments in order to create spaces for contemplative play. Most of these titles reward players for slowness, or prolonged stillness. These games also entice players to think about the game as an ongoing process, enticing players to come back to it after several months of not playing. Within these games, a domineering AI doesn't interfere with the whims of a player, and as a result these games encourage players to think about games in a way that isn't primarily focused on narrative.

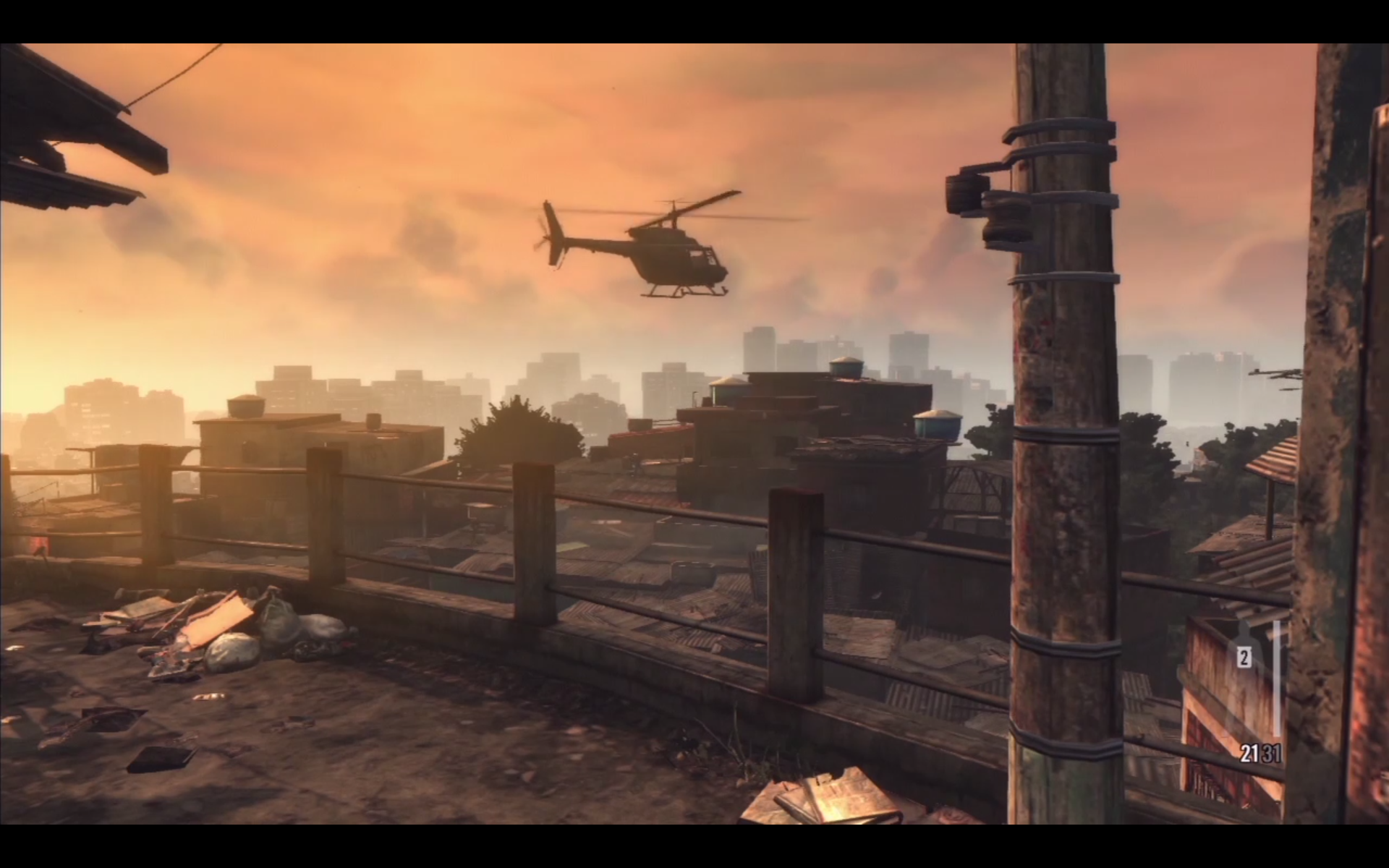

Tale of Tales, The Endless Forest (2007)

A fitting example of this is Tale of Tales’ Endless Forest (2007).

This interactive screensaver allows players to control an elk-like

creature through various locations and vignettes under a dense, mythical

forest canopy. Players interact with other elks over a network and

communicate through non-verbal gestures like bowing, stomping hooves and

dancing. Although interaction is a central component of the game, an

equally important element is the way the game rewards players for

free-ranging exploration and stillness. In order to activate certain

areas of the forest, the player must remain still, allowing their avatar

to come to full resting position. The longer the player remains in

these calm states, the more the scene reveals itself to the player.On top of rewarding players for their stillness, Endless Forest also entices players by integrating an element of downtime that few games would usually implement. The more time a player has spent online (either allowing their computer to remain passively connected, or in exploring the forest), the more their avatar visibly ages and matures. At first, the player's elk is only a fawn, but as the game records their participation, the avatar grows into a sagacious beast. This element of Tale of Tales’ design indicates to the player that their prolonged experience of stillness and rest – both on the part of the player and on the part of their computer going to sleep – will result in noticeable character development, suggesting that patience and contemplation are virtuous qualities of a player.

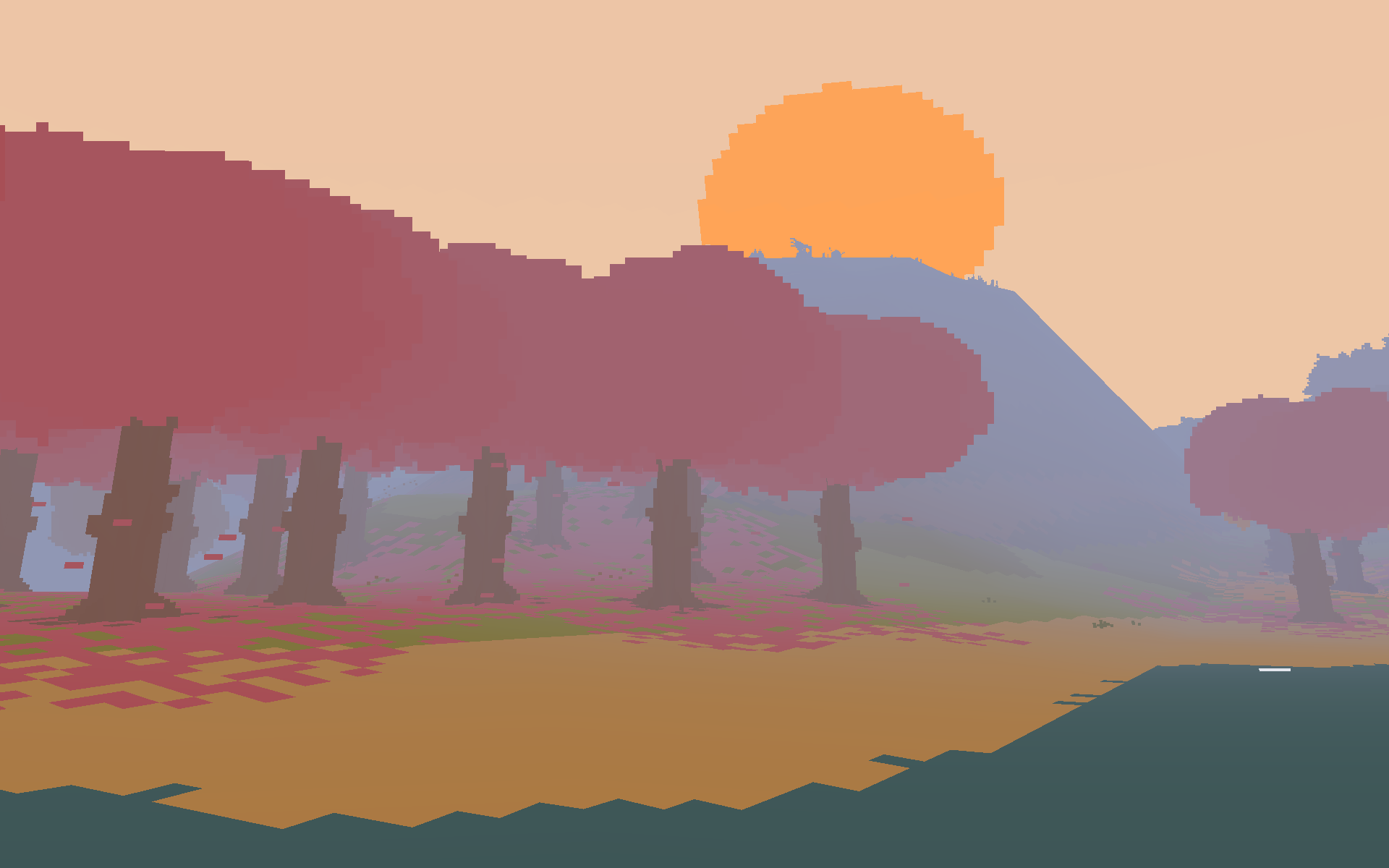

Another notable example can be found in the critically lauded Journey, developed by thatgamecompany. In this title, players awake in the desert surrounded by gravestones and ruins. As the player moves toward intricate and massive slabs of broken masonry, they encounter floating pieces of fabric that encircle them and provide temporary flight. As in Endless Forest, players find anonymous companions with whom to explore the ruins of this game. Through activating eroded altars, pillars, and frozen columns of fabric with their avatar's voice, the player uncovers a simple narrative about an ancient civilization that sought refuge in a distant illuminated mountain peak. The player then works alongside their unnamed partner to reach the summit through perilous trials and dreadful conditions.

thatgamecompany, Journey (2012)

During this relatively short adventure,

players can either choose to advance from scene to scene without the

assistance or company of a sidekick, or else collaboratively explore the

environments of the game. As the game progresses, however, players have

to stick together and sing to one another to enliven each other’s

spirits in order to avoid freezing into immobility. This simple gesture

brings players together, not just to assist one another, but also to

playfully communicate a mutual bond that could only happen through a

networked video game.

The beauty of Journey does not just come from

its incredible visual design, or from its lack of a pushy algorithm.

Its gameplay allows players to collaboratively linger in luscious

surroundings. The simple joy of gliding alongside your companion across

the glimmering sands of Journey’s environment is captivating in

a way that is richer for being shared. Within certain moments of the

game, the camera is purposefully positioned to focus the attention of

the player toward vast romantic vistas. During one particular scene,

players speed along a sloping dune through a once-palatial space,

catching glimpses through sun-soaked archways of an abandoned city

nestled in the valley below. This moment references the popular game

motif of an anxiety-driven downhill chase scene, but here it has been

repurposed as a meditative experience for contemplating the unforgiving

forward march of time.

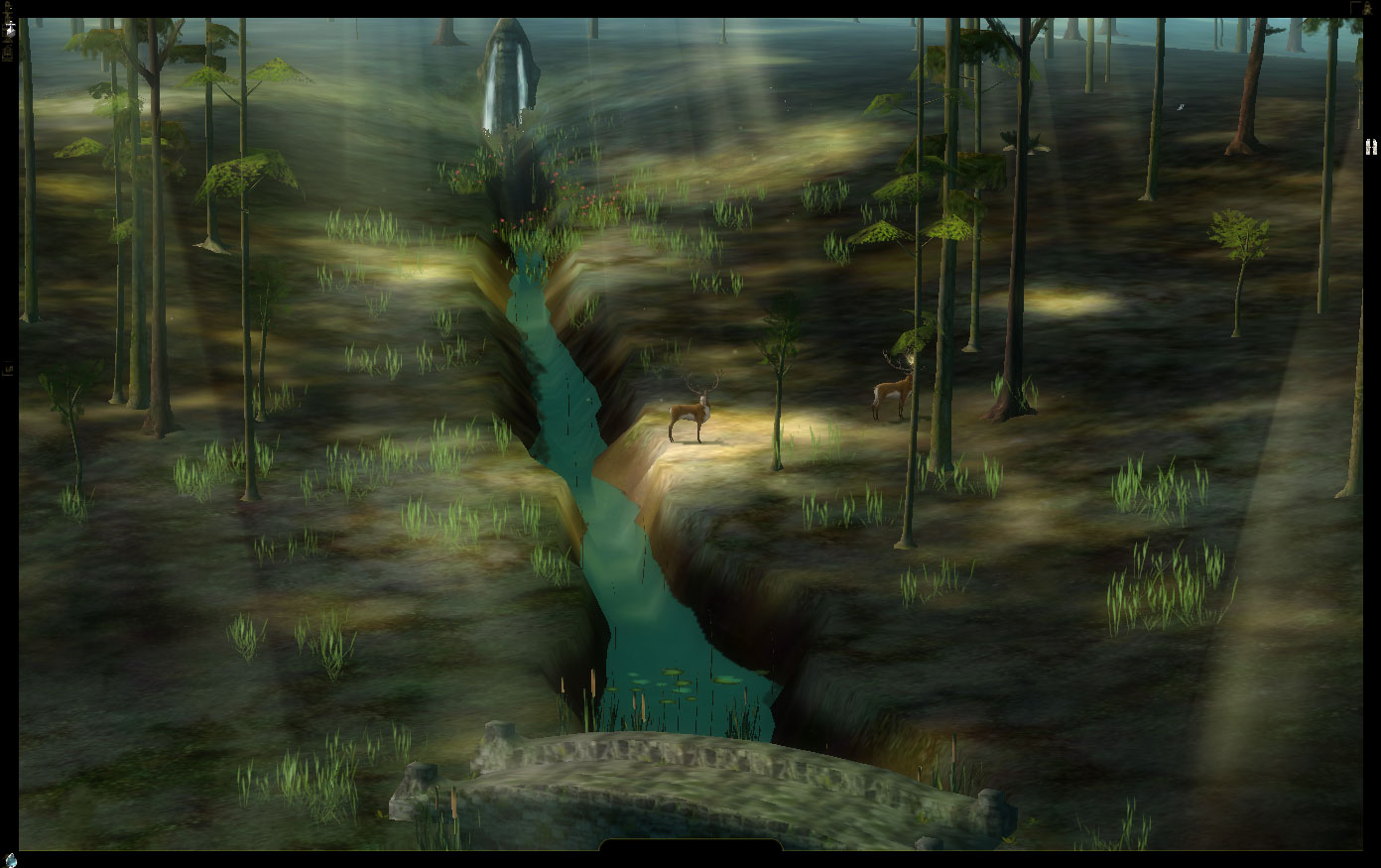

Similarly, Ed Key and David Kanaga's Proteus also uses the motif of a meandering landscape in order to ruminate on the passage of time. Proteus, however, is less concerned with narrative than Journey,

in that the primary experience revolves around exploring soundscapes

generated by a low-bit, procedurally generated island. The player

encounters various creatures and totems that have specific tones that

all contribute to a vibrant, synthesized soundtrack. The score then

dynamically changes as players explore the topology of the island. Like Endless Forest,

players are encouraged to stand stationary in specific moments of the

landscape in order to affect the visual and aural experience of their

surroundings. One such instance involves standing within a circle of

figures that resemble shaman of some sort. After watching the sunset,

the distant stars shimmer vigorously and further texture the nocturnal

harmonics.

Ed Key and David Kanaga, Proteus (2013)

As the player explores the

island further, they find a concentration of circling particles that

creates a portal into another season on the island. Each season then has

its own unique sound, adding new layers and new interactions to

explore. In Fall, the falling leaves from the trees blip upon hitting

the amber colored ground. In Spring, the light showers create twinkling

arpeggios that lilt atop the dense chords of blossoming flowers. In a

nod to Vivaldi's masterwork, Key and Kanaga offer a new aural texture

for each season. In doing so, they invite players to consider the

changes that occur to the landscape and to themselves, while frolicking

through luscious hilltops and valley meadows.

All three titles create

contemplative space within the video game as a way to challenge and

present alternatives for Rafman's digging man. The structure of Endless Forest

rewards stillness and open-ended exploration, in marked contrast with

the irrepressible, attention-demanding narratives that occur in triple-A

titles. Journey builds on this strategy with a structure that

encourages collaborative lingering, engendering shared contemplative

experiences within a simple narrative structure. And Proteus abandons narrative entirely, while offering a rich sensory experience. In particular, Proteus

suggests that the affect of the virtual environments presented in games

is not solely dependent on their graphical similitude to the physical

world. Instead, all three of these games offer oases of respite within a

wasteland of aggressive blockbusters, creating contemplative spaces in

which to approach a kind of interactive rapture. - rhizome.org/

Still Life (Betamale), 2013

9-Eyes, ongoing

Remember Carthage, 2013

Remember Carthage Carthage is a new short film by artists Jon Rafman and Rosa Aiello, presented online for the New Museum’s monthly First Look series.

Codes of Honor, 2011

Codes of Honor

Jon Rafman

Chinatown Fair arcade closed down on February 28th, 2011, after over 50 years. Gamers are still in mourning. CF, as it was known, was one of the last video game arcades in America where one could count on finding top-level competition. I spent the better part of 2009 in that dingy, dim-lit arcade at the end of Mott street, which was the battlegound for the best players in the history of pro-gaming.

The first Street Fighter release in a decade —Street Fighter IV —just came out, sparking a short-lived renaissance in the fighting game community. I got to know the regulars at the arcade and began conducting daily video interviews, asking them to recall their greatest memories at the joysticks. I set up a YouTube channel, which was widely followed and the comment section became a major forum for debate in the community. During that year, I learned that to be a top-pro one could not simply master the technical aspect of the game; to compete at the highest level one needed to have a strong character and a deep understanding of human psychology. I learned that pro-gamers ascribe to the values and virtues of the classical archetypes of yore: honor, respect for the other, and excellence. Hardcore gamers have an experience of acheivement so intense that, although limited in scope and time, it is forever difficult to equal. Although nothing can rival the high they get from defeating a worthy opponent or the reputation during their reign, the fame is as fleeting as the high of the win. And so I learned of the tragic element that is inherent to the experience of video gaming.

I learned of many celebrated gamers but as legends go, no one topped Eddie Lee, the East Coast Champ. Eddie is recognized as the pioneer of the New York-style of gameplay, a variation of the “Turtle-Style.” Considered the most frustrating of all combat forms, turtling requires infinite patience. The strategy demands that one play a zero-risk game, keeping the perfect distance from the opponent, waiting for the enemy to make a mistake, but never taking the initiative, just waiting patiently for him to slip. When he finally does, he is punished. This was the style Eddie Lee felt he had to pass on — not the brave crowd-pleasing grace of the “Rushdown” fighter, but the calculated brutality of the defensive master that shuns all desire for spectacle. Part of the appeal to the story of Eddie Lee was that he suddenly and mysteriously dropped out of the tournament scene at the height of his powers. It was rumoured that he went on to use these very skills to become a successful Wall Street day trader.

When I found the legend of Eddie Lee, I found the center to my film. In order to portray the tension between regret for the time spent playing without a visible legacy and nostalgia for the thrill of the game, I integrate three perspectives: i) a narrator in a virtual world who reminisces about his days as a pro-gamer, ii) a Chinatown Fair regular who recounts his greatest memory, and iii) classic cut-scenes from the games themselves. In this way, Codes of Honor moves through actual, virtual, and imaginary space and time.

Rather than adopting the popular perspective on gaming as a way of escaping life, engaging in violence or being antisocial, the film focuses on the gamers’ pure joy in their hard-sought achievements, the thrill of high-level competition, the significance it gives their lives, and the communities they create. We see the journey of a professional gamer as he moves from the prized moment when he masters a game or defeats an arch-rival to the despairing moment when he realizes his legacy will soon be forgotten. We see him confront a question that faces us all: in a world where history and tradition mean less and less, how do we achieve redemption? How do we even construct a continuous self?

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life, 2008-2011

You, the World and I, 2010

You, the World and I (.com)

New Age Demanded, ongoing

Woods of Arcady, 2010

BNPJ.exe (with Tabor Robak), 2010

Paint FX (R.I.P.), 2009

Deities & Demigods, 2011

New Age Demanded, 2010

Tokyo Color Drifter #1, 2009

DU3L, 2009

Sleeping Shepherd Boy .com, 2009

D-R-E-A-M-G-I-R-L .com, 2009

The Death of Google's First Server, 2008

The Horror The Horror .info, 2008

Portrait of a Net Artist as a Young Man .com, 2008

Forms of Melancholy, 2008

Thirty-Six Views of Ryugyong, 2008

Spam Fragments (pdf), 2008

LeWitt2 LeWitt3 LeWitt4 Hallway1 Hallway2, 2006

Unreliable Narrators , 2005

Documenting The "Vegas Of The Maghreb" Through Virtual Environments: Q&A With Jon Rafman And Rosa Aiello

http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/documenting-the-vegas-of-the-maghreb-through-virtual-environments-qa-with-jon-rafman-and-rosa-aiello

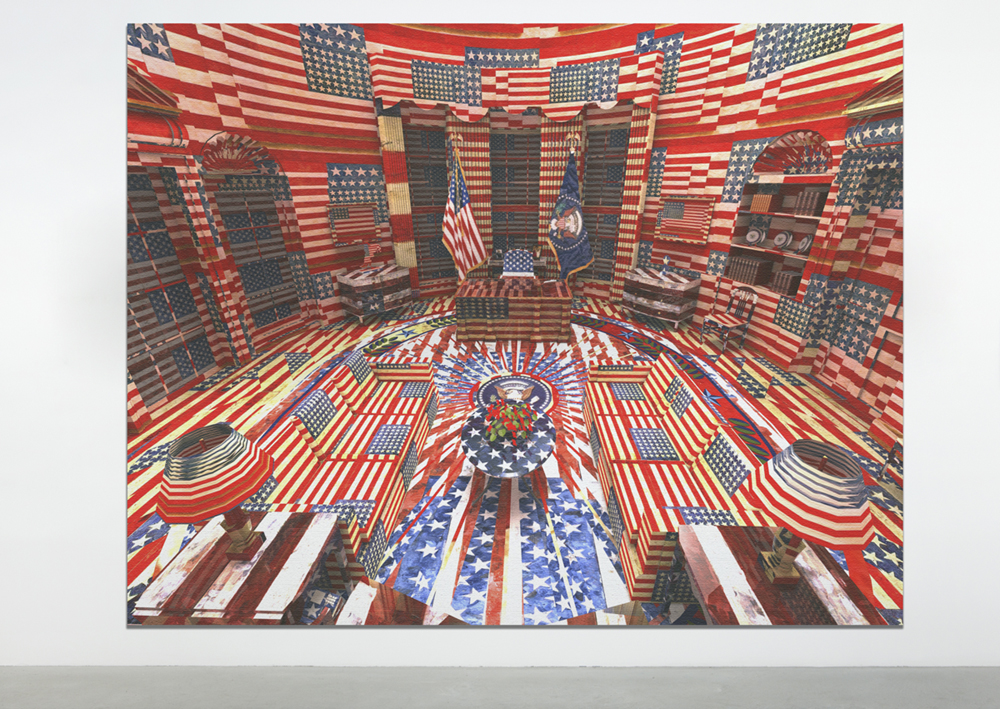

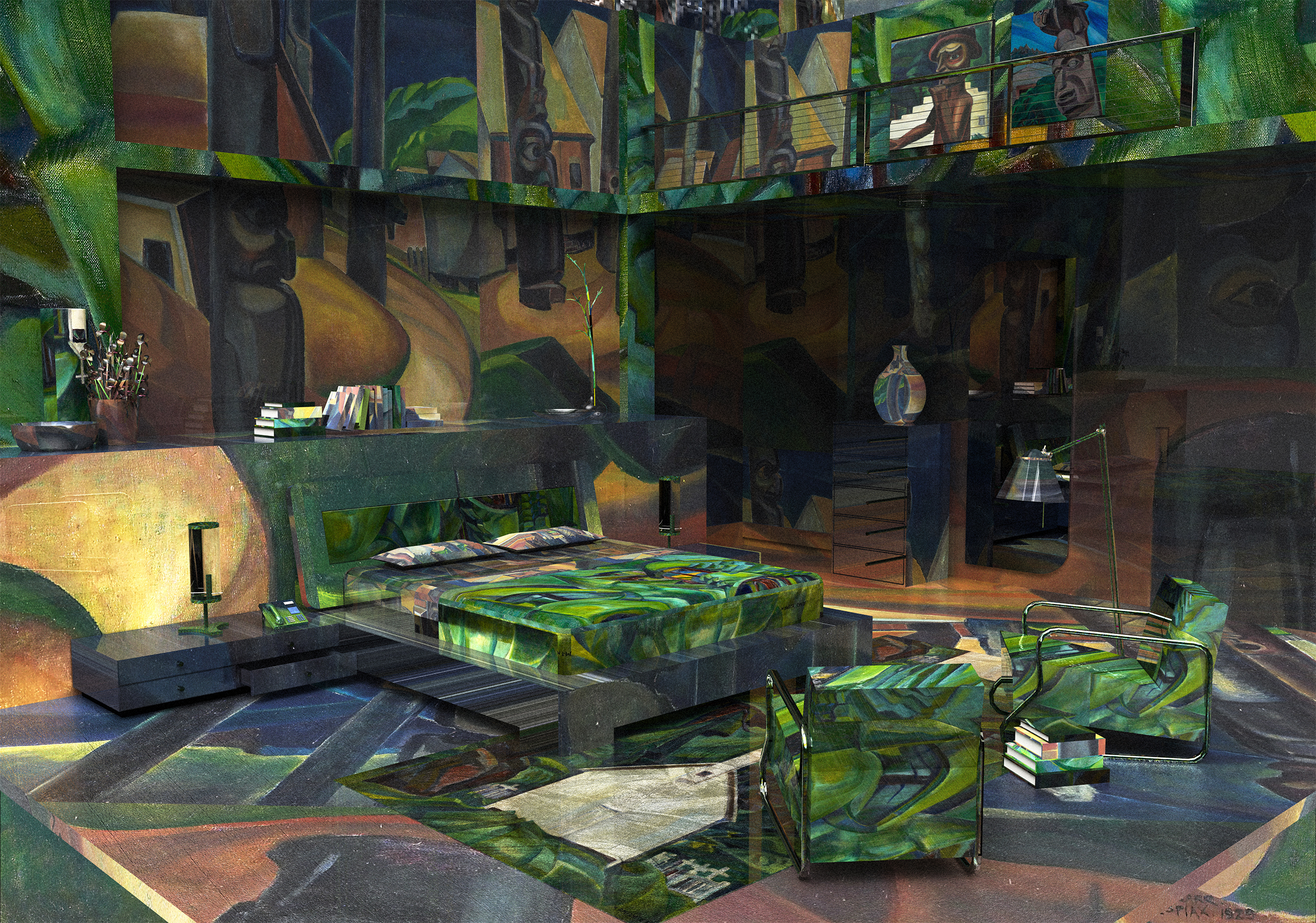

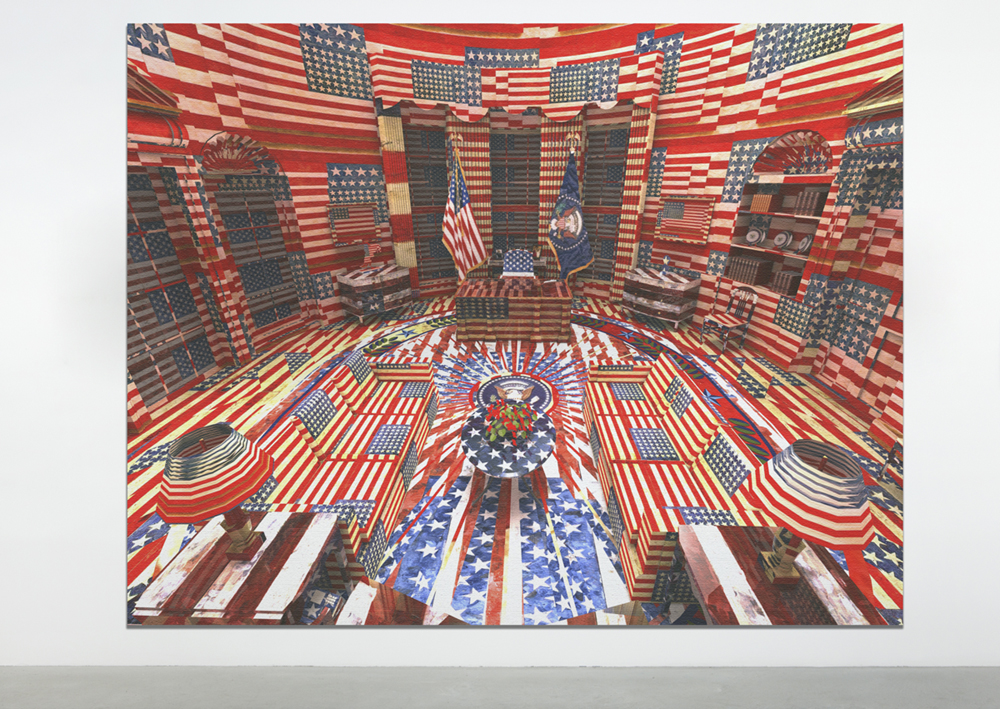

Brand New Paint Job

http://www.brandnewpaintjob.com

Read more about BNPJ here and here.

Jon Rafman, Fernand Leger Bomb, 2010

Some recent works over on Jon Rafman’s excellent piece Brand New Paint Job. Here so many crossovers are brought into proximity… the post-gallery, post-exhibition reality of a collectable painting largely as an adornment to the interior decor of the collector, bent around their objects like a kind of philosophical wallpaper, but in Rafman’s handling such a suggestion occurs skinned upon 3d alreadymades from Google 3D Warehouse. In this way the project may also wryly tackle one of painting’s most hotly defended and greatest historic fears: the decorative.

Each instance is a consideration between an object and a painting, potentially pitting the uselessness of paintings against the function of objects, dialing that hallowed and receding ground between art and design. Or casting painting in the lead role of Tradition for the visual, a position that blankets current image based material found within the internet. Seen in this way as an ancestor, out of context and sampled, Rafman may seem to suggest history is ultimately wrapped around whatever we do. This is interesting, particularly as history is a cumulative process, you know, history is actually increasing. The further into the future we go, the more history we must carry. We might not have to carry it as much as before if history is online, because now it’s just chilling in your pocket. In any case we could, like they did 100 years ago, always dump history by the wayside to lighten the load. Break free. Or as we see in these works by Jon Rafman, we could just continue to carry our burden awares - and do it with equal parts style and wit.

In each piece iconic proponents from the history of painting are summoned in the house of Google, relegated to the status of add-on surfaces, custom bitmap textures, literally shrink wrapped around pieces of online community objects. Is history fitting the current or is the current fitting history? Positioning painting in this way brings it into the realm of an exclusive wallpaper, a humorous play with interior designer chic. In some of the interior living spaces where Rafman has completely covered every object in a room with the repetition of a single painting, the room becomes a domestic shrine to a work, it’s facets a vortex, as objects are lost to and within a mutation of planes. Is this a new painting? Or a new paint job? With the critical Auction House Heights (AHH) of painting now represented also as google Image Search Stock (ISS), history can be understood as layers applied over or under the present, like a paint job.

by Ry David Bradley

—-

Some of Jon’s work is on view in New York at the latest offering from the New Museum, a show entitled FREE which opens tomorrow. For your reading delight, Jon may write a mini-essay for PAINTED,ETC. in the close of this year.

An excerpt from the show text, curated by Lauren Cornell:

Today, culture is more dispersed than ever before. The web has broadened both the quantity and kind of information freely available. It has distributed our collective experience across geographic locations; opened up a new set of creative possibilities; and, coextensively, produced a set of challenges. This fall, the New Museum will present “Free,” an exhibition including twenty-three artists working across mediums—including video, installation, sculpture, photography, the internet, and sound—that reflects artistic strategies that have emerged in a radically democratized cultural terrain redefined by the impact of the web. “Free” will propose an expansive conversation around how the internet has affected our landscape of information and notion of public space. The philosophy of free culture, and its advocacy for open sharing, informs the exhibition, but is not its subject. Instead, the title and featured works present a complex picture of the new freedoms and constraints that underlie our expanded cultural space.

• 18 October 2010

Jon Rafman, KOOL AID MAN IN SECOND LIFE, 2009.

via Kool Aid Man in Second Life.

“People make crush art about you all the time, don’t they?” That’s the first question I asked Jon Rafman one month ago after he discovered I was embarking upon an ongoing multi-media performance inspired by his work. Our conversation provided my first hint into Rafman’s process. He wanted to know what I’d done between the time I left work and the time I arrived at home, the name of the office building, where my roommate was born, the details of my relationship to certain net artists, and a host of other very specific questions which I later saw as part of his process for, and reverence toward, the construction of one’s personal narrative. The truth, though he wouldn’t admit it, is that Jon Rafman is one of the net art community’s most respected and beloved figures. This prestige, it seems to me, relates to his ability to position himself in shamanistic roles, as director, storyteller, and tour guide, as the middle man exploring essential concepts of modernity/contemporary experience, and then processing and framing them into narratives. His work is concerned with virtual worlds, self-identity, and the collapse of high/low art. He is the artist/curator behind Googlestreetviews.com and the cartoonish internet flâneur directing tours through Second Life as Koolaidmaninsecondlife.com.

Rafman’s Kool-Aid Man avatar is one of his most primary characters, taking appointments and leading tours through Second Life worlds both utopian and fetishistic, as well as starring in a collection of stills and films directed by Rafman himself, which humorously contrast the avatar’s round red body against the super sexy alter egos much more commonly found in Second Life. The tours are primarily directed between virtual avatars, however Rafman also performs the tours live, inviting audience members to directly interact and inform the journey, as he subtly contextualizes and frames the experience. The Kool-Aid Man avatar, as it relates to Rafman’s body of work as a whole, is an externalized representation of Rafman’s honest and committed artistic struggle to construct and examine self in virtual culture.

When Rafman agreed to do this BOMB interview, our collaboration began with a series of ideas and links shared over g-chat conversations, emails, late-night video chats and Skype calls. We discussed constructing a short film inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s interview of Woody Allen or designing a text interview where every word or phrase hyperlinked to another obscure place on the web (à la the early papperad website). Ultimately, I confessed that my true intention for this interview was to reveal “the real” Jon Rafman. Our discussion over Skype (transcribed below) proposes that perhaps “revealing the real” is… well, I wouldn’t want to give away a story right at the very beginning.

BOMB Presents Kool-Aid Man in Second Life by Jon Rafman in collaboration with Lindsay Howard, 2010 from BOMB Magazine on Vimeo.

Jon Rafman, KOOL AID MAN IN SECOND LIFE, 2009.

via Kool Aid Man in Second Life.

Jon Rafman, 58 LUNGOMARE 9 MAGGIO, BARI, PUGLIA, ITALY. 2009. Installation in the artist’s studio.

via Google Street Views

Jon Rafman, SLEEPING SHEPHERD BOY, 2009.

via Sleeping Shepherd Boy

'Brand New Paint Job' catalog by Domenico Quaranta, 2011 (pdf)

Interview with Lodown Magazine, 2010 (pdf)

'IMG MGMT - The Nine Eyes of Google Street View' essay, 2009

16 Google Street Views booklet, 2009 (pdf)

Zach Feuer Gallery, New York

Seventeen Gallery, London

Future Gallery, Berlin

Still Life (Betamale), 2013

9-Eyes, ongoing

Remember Carthage, 2013

Remember Carthage Carthage is a new short film by artists Jon Rafman and Rosa Aiello, presented online for the New Museum’s monthly First Look series.

Jon Rafman and Rosa Aiello, Remember Carthage, 2013 (still). Video on loop, color, sound. Courtesy the artists

An essay film in the tradition of experimental documentarians like Chris Marker or Harun Farocki, Remember Carthage

takes the viewer on an epic journey in search of an abandoned resort

town deep in the Sahara desert. However, one travels not through

archival or personal images but through footage sourced from PS3 video

games and Second Life, depicting ancient civilizations that seem at once

familiar and totally fantastical. Presented in conjunction with the

exhibition “Museum as Hub: Walking Drifting Dragging,” which centers on

artist expeditions, Remember Carthage is a first-person journey

through a historical fantasia that highlights the fictionalizing and

exoticization of culture within gaming and virtual worlds.

The voyage begins on the swaying deck of a ship in unnamed waters

and proceeds through a myriad of different landscapes, from arid deserts

to the gaudy interiors of what appear to be Persian palaces, to

barrooms and bedrooms—each new scene unfolding in sync with the

narrator’s melancholic remembrances. As in other works by Rafman, a

feeling of alienation and loneliness structures the story, with the

narrator searching for a connection and yet unable to grasp what is real

or stable around him. In Remember Carthage, the filmmakers

emphasize how digital media makes history seem both totally accessible

through archival information and, at the same, completely foreign to us.

Here, the narrator’s search for the abandoned town is rendered

increasingly futile as he traverses a landscape where markers of time

and place often appear to be unmoored, floating signs. And, as his

journey continues, he becomes unable to distinguish authentic sites from

simulated versions.

The repetitive and circular sequencing of the film, with recurring locations and characters, furthers the protagonist’s sense of dislocation and interpolates the logic of gameplay—continual death and resurrection—into his journey. It is unclear whether the narrator in Remember Carthage ever arrives; despite constantly moving, he is caught in a horizontal, virtual dreamworld where his goals become ever more distant.

Jon Rafman is an artist, filmmaker, and essayist whose work explores the impact of technology on consciousness. His films and artwork have gained international attention and have been exhibited at the New Museum, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and the Saatchi Gallery in London. Rafman’s work has been featured in Modern Painters, Frieze, the New York Times, and Harper’s.

Rosa Aiello is a writer and video artist. She has recently completed an MA at Oxford in literature and philosophy, and an artist’s residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts. Her writing and video practice deals with the limits of language, reason, and humanness. Aiello has been exhibited at the Museo d’arte contemporanea Roma and the Festival de Nouveau Cinéma in Montreal.

Lauren Cornell

www.newmuseum.org/

The repetitive and circular sequencing of the film, with recurring locations and characters, furthers the protagonist’s sense of dislocation and interpolates the logic of gameplay—continual death and resurrection—into his journey. It is unclear whether the narrator in Remember Carthage ever arrives; despite constantly moving, he is caught in a horizontal, virtual dreamworld where his goals become ever more distant.

Jon Rafman is an artist, filmmaker, and essayist whose work explores the impact of technology on consciousness. His films and artwork have gained international attention and have been exhibited at the New Museum, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and the Saatchi Gallery in London. Rafman’s work has been featured in Modern Painters, Frieze, the New York Times, and Harper’s.

Rosa Aiello is a writer and video artist. She has recently completed an MA at Oxford in literature and philosophy, and an artist’s residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts. Her writing and video practice deals with the limits of language, reason, and humanness. Aiello has been exhibited at the Museo d’arte contemporanea Roma and the Festival de Nouveau Cinéma in Montreal.

Lauren Cornell

www.newmuseum.org/

Codes of Honor, 2011

Codes of Honor

Jon Rafman

Jon Rafman, Codes of Honor, 2011

Chinatown Fair arcade closed down on February 28th, 2011, after over 50 years. Gamers are still in mourning. CF, as it was known, was one of the last video game arcades in America where one could count on finding top-level competition. I spent the better part of 2009 in that dingy, dim-lit arcade at the end of Mott street, which was the battlegound for the best players in the history of pro-gaming.

The first Street Fighter release in a decade —Street Fighter IV —just came out, sparking a short-lived renaissance in the fighting game community. I got to know the regulars at the arcade and began conducting daily video interviews, asking them to recall their greatest memories at the joysticks. I set up a YouTube channel, which was widely followed and the comment section became a major forum for debate in the community. During that year, I learned that to be a top-pro one could not simply master the technical aspect of the game; to compete at the highest level one needed to have a strong character and a deep understanding of human psychology. I learned that pro-gamers ascribe to the values and virtues of the classical archetypes of yore: honor, respect for the other, and excellence. Hardcore gamers have an experience of acheivement so intense that, although limited in scope and time, it is forever difficult to equal. Although nothing can rival the high they get from defeating a worthy opponent or the reputation during their reign, the fame is as fleeting as the high of the win. And so I learned of the tragic element that is inherent to the experience of video gaming.

I learned of many celebrated gamers but as legends go, no one topped Eddie Lee, the East Coast Champ. Eddie is recognized as the pioneer of the New York-style of gameplay, a variation of the “Turtle-Style.” Considered the most frustrating of all combat forms, turtling requires infinite patience. The strategy demands that one play a zero-risk game, keeping the perfect distance from the opponent, waiting for the enemy to make a mistake, but never taking the initiative, just waiting patiently for him to slip. When he finally does, he is punished. This was the style Eddie Lee felt he had to pass on — not the brave crowd-pleasing grace of the “Rushdown” fighter, but the calculated brutality of the defensive master that shuns all desire for spectacle. Part of the appeal to the story of Eddie Lee was that he suddenly and mysteriously dropped out of the tournament scene at the height of his powers. It was rumoured that he went on to use these very skills to become a successful Wall Street day trader.

When I found the legend of Eddie Lee, I found the center to my film. In order to portray the tension between regret for the time spent playing without a visible legacy and nostalgia for the thrill of the game, I integrate three perspectives: i) a narrator in a virtual world who reminisces about his days as a pro-gamer, ii) a Chinatown Fair regular who recounts his greatest memory, and iii) classic cut-scenes from the games themselves. In this way, Codes of Honor moves through actual, virtual, and imaginary space and time.

Rather than adopting the popular perspective on gaming as a way of escaping life, engaging in violence or being antisocial, the film focuses on the gamers’ pure joy in their hard-sought achievements, the thrill of high-level competition, the significance it gives their lives, and the communities they create. We see the journey of a professional gamer as he moves from the prized moment when he masters a game or defeats an arch-rival to the despairing moment when he realizes his legacy will soon be forgotten. We see him confront a question that faces us all: in a world where history and tradition mean less and less, how do we achieve redemption? How do we even construct a continuous self?

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life, 2008-2011

Is Second Life the theatre of the absurd? Ask the Kool-Aid Man in SL

Posted by Bettina Tizzy

Net Art/New Media artist Jon Rafman has been getting rave reviews and first-rate press coverage with the likes of Rhizome and other coveted art outlets as the Kool-Aid Man in Second Life®, offering free guided tours in-world. His dedicated website features a promo video that I guarantee will produce an emotion in Second Life residents, and invites folks to sign up. I first got wind of this video when Paddy Johnson of the art blog Art Fag City twittered “Best Link Ever! Kool Aid Man gives a guided tour of Second Life and it doesn't suck (like most SL art)!”

Unlike every other machinima I have seen that strives so hard to get past the technical challenges to convey the beauty, the love, the horror, the possibilities within, because of, and thanks to our virtual lives, Jon’s is a breezy, often hilarious tour that celebrates the absurdity of our immersiveness. Second Life users will recognize many favorite builds and installations.

WARNING: This video contains a lot of X-rated content.

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (.com) - Tour Promo from on Vimeo.

Jon rezzed in Second Life on 12/10/2006 but used it sporadically until recently. I’ve spent a couple of evenings this week in-world with him and I can tell you that he’s a pleasant, intensely curious, and intelligent fellow. He received his Master of Fine Arts degree from the Art Institute of Chicago, and double majored in philosophy and English. I’d call him spontaneous, easily bored, and a fascinated yet detached explorer. I expect you’ll be as curious as I was to hear what he had to say about this. I sent him some rather open-ended questions via email to see what I’d get back.

Why did you elect to omit music to that video?

Jon Rafman: There is a tendency to use music as a crutch and let the soundtrack manipulate the tone of the work. I want the visual aspects of the video to speak for themselves. The formal qualities of the landscapes should dictate the mood of the piece rather than the soundtrack. Moreover, I always felt like the generic in-world sound effects, like the ominous low-pitched wind that blows across SL, creates a subtler emotional resonance than music.

Kool-Aid Man is on a quest for sublime kitsch in Second Life. Music used inappropriately corrupts the underlying mundanity of my avatar's search.

At certain points in the video there is music; however it's always what was streaming in that sim during the time of capture.

I don't want to assume anything so I have to ask: Are you really going to give guided tours?

Jon Rafman: I like this question. It forces me to ask myself: Where's the "Art" happening in this project? How important is the actual tour-giving process to the Kool-Aid Man in SL? Is the core of the artwork the video and photo collections? Or is it the process of the tour itself and the interaction with people in a virtual world that is the core of my project?

Yes, I'm giving tours. It is not a hoax!

But...

Even if the tours were a hoax and the project existed only conceptually, I'd be cool with that, too. I'm a big fan of work that walks the line between fake and real, ironic and tragic, fiction and documentary.

Do you intend to continue your work in Second Life?

Jon Rafman: I'm currently integrating some videos I've captured in SL into a larger documentary film about professional video gamers. I'm searching for ways to transcend the kitschiness inherent in the SL aesthetic and haven't decided yet on how significant of a role SL will have in the film yet.

I'm also toying with some story ideas for a few Kool-Aid Man in Second Life short video series. There's so much potential with Second Life machinima, but I have yet to see a work of machinima that's truly inspired me. Maybe I haven't looked hard enough though.

What do you want Second Life'rs to know about you most of all?

Jon Rafman: I found an analogy for surfing the web in the act of exploring Second Life as Kool-Aid Man. User-generated realms of Second Life can be viewed as a 3D virtual expression of the Internet’s anarchic psyche. Kool-Aid Man is my alter-ego, a secular icon that resonates with decades come and gone.

I see Kool-Aid Man as a self-conscious professional web surfer “breaking through walls” into various Second Life communities and subcultures. He never fully fits in, but he empathizes with whatever he passes. Like Baudelaire’s Flaneur, wandering the arcades of Fin-du-Siecle Paris, Kool-Aid Man keeps a cool and curious eye, strolling through the virtual world in search for the banal sublime. Kool-Aid Man's motto is best summed up by a line at the beginning of Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil: "I've been round the world several times and now only banality still interests me. On this trip, I've tracked it with the relentlessness of a bounty hunter."

I wondered as I read Jon's response if he was aware that French author, photographer and film director Chris Marker is very active in Second Life. Perhaps there are two bounty hunters then? It is unlikely we'll ever know, given that Marker famously does not take interviews.

Jon Rafman: The Kool-Aid Man in Second Life project is partly an attempt to investigate certain 'outdated' concepts from bygone eras and to reframe them or test them out in distinctly contemporary pop-cultural contexts. I am interested in the disjuncture between earlier uses and my own use and what this reveals about how consciousness has changed over the past decades. Whether a fundamental change has occurred is an open question as the forms of alienation that existed one hundred years ago are present today in mutated forms. But these subtle changes are revealing of what it means to be alive today. What are these subtle changes I mention?

The fragmentation that started with the emergence of mass culture has only intensified. Decentralized global society is epitomized in the World Wide Web. This is not to say that the power of centralized authority has declined or that a new genuine techno-democracy has been achieved. This is far from the case; I’m interested in the ways that self-regulating authority manifests itself from the ground up.

I do think that the task of grasping the present clearly has become more difficult because so much now obscures us from seeing it. I frame my quest for the banal sublime as doomed from the beginning because I am trying to highlight the loss of a certain type of consciousness.

Am I nostalgic for Fin-du-Siècle Paris?:

Yes, my project is a somewhat melancholic attempt at pointing towards the importance of understanding the historical context in the digital age. I can’t deny my nostalgia for earlier modern periods; however I am also aware that the image of the past that I yearn for reveals less about the past and more about an acute lack that exists in the present. And it is this “lack” that I want to point towards.

A Conversation with Jon Rafman (NSFW video) - Bad at Sports

A conversation with Jon Rafman about Kool-Aid Man (in Second Life) - Martin, it's already now!

Is Second Life the theatre of the absurd? Ask Kool-Aid Man in SL - NPIRL

Selected Press:

Kino-Eye, the video cyborg - art:21org

Kool-Aid Man to Get It On With Avatar's Neytiri in 'Second Life' - Asylum

Best Link Ever! Guided Tours of Second Life with Kool-Aid Man - Art Fag City

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (2009) - Rhizome

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life.com - asquare.org : Newtork Research

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life? OH YEAH! - An I'm not Lyng

Kool-Aid MAn is Giving NSFW Tours in Second Life [Wow, There's Still a Second Life?] - Boing Boing

Jon Rafman (Kool-Aid Man in Second Life) - Beautiful/Decay Magazine

Site Scavenging - Houston Press

Poke and Topiary Text Lead - The Great God Pan is Dead

Net Art/New Media artist Jon Rafman has been getting rave reviews and first-rate press coverage with the likes of Rhizome and other coveted art outlets as the Kool-Aid Man in Second Life®, offering free guided tours in-world. His dedicated website features a promo video that I guarantee will produce an emotion in Second Life residents, and invites folks to sign up. I first got wind of this video when Paddy Johnson of the art blog Art Fag City twittered “Best Link Ever! Kool Aid Man gives a guided tour of Second Life and it doesn't suck (like most SL art)!”

Unlike every other machinima I have seen that strives so hard to get past the technical challenges to convey the beauty, the love, the horror, the possibilities within, because of, and thanks to our virtual lives, Jon’s is a breezy, often hilarious tour that celebrates the absurdity of our immersiveness. Second Life users will recognize many favorite builds and installations.

WARNING: This video contains a lot of X-rated content.

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (.com) - Tour Promo from on Vimeo.

Jon rezzed in Second Life on 12/10/2006 but used it sporadically until recently. I’ve spent a couple of evenings this week in-world with him and I can tell you that he’s a pleasant, intensely curious, and intelligent fellow. He received his Master of Fine Arts degree from the Art Institute of Chicago, and double majored in philosophy and English. I’d call him spontaneous, easily bored, and a fascinated yet detached explorer. I expect you’ll be as curious as I was to hear what he had to say about this. I sent him some rather open-ended questions via email to see what I’d get back.

Why did you elect to omit music to that video?

Jon Rafman: There is a tendency to use music as a crutch and let the soundtrack manipulate the tone of the work. I want the visual aspects of the video to speak for themselves. The formal qualities of the landscapes should dictate the mood of the piece rather than the soundtrack. Moreover, I always felt like the generic in-world sound effects, like the ominous low-pitched wind that blows across SL, creates a subtler emotional resonance than music.

Kool-Aid Man is on a quest for sublime kitsch in Second Life. Music used inappropriately corrupts the underlying mundanity of my avatar's search.

At certain points in the video there is music; however it's always what was streaming in that sim during the time of capture.

I don't want to assume anything so I have to ask: Are you really going to give guided tours?

Jon Rafman: I like this question. It forces me to ask myself: Where's the "Art" happening in this project? How important is the actual tour-giving process to the Kool-Aid Man in SL? Is the core of the artwork the video and photo collections? Or is it the process of the tour itself and the interaction with people in a virtual world that is the core of my project?

Yes, I'm giving tours. It is not a hoax!

But...

Even if the tours were a hoax and the project existed only conceptually, I'd be cool with that, too. I'm a big fan of work that walks the line between fake and real, ironic and tragic, fiction and documentary.

Do you intend to continue your work in Second Life?

Jon Rafman: I'm currently integrating some videos I've captured in SL into a larger documentary film about professional video gamers. I'm searching for ways to transcend the kitschiness inherent in the SL aesthetic and haven't decided yet on how significant of a role SL will have in the film yet.

I'm also toying with some story ideas for a few Kool-Aid Man in Second Life short video series. There's so much potential with Second Life machinima, but I have yet to see a work of machinima that's truly inspired me. Maybe I haven't looked hard enough though.

What do you want Second Life'rs to know about you most of all?

Jon Rafman: I found an analogy for surfing the web in the act of exploring Second Life as Kool-Aid Man. User-generated realms of Second Life can be viewed as a 3D virtual expression of the Internet’s anarchic psyche. Kool-Aid Man is my alter-ego, a secular icon that resonates with decades come and gone.

I see Kool-Aid Man as a self-conscious professional web surfer “breaking through walls” into various Second Life communities and subcultures. He never fully fits in, but he empathizes with whatever he passes. Like Baudelaire’s Flaneur, wandering the arcades of Fin-du-Siecle Paris, Kool-Aid Man keeps a cool and curious eye, strolling through the virtual world in search for the banal sublime. Kool-Aid Man's motto is best summed up by a line at the beginning of Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil: "I've been round the world several times and now only banality still interests me. On this trip, I've tracked it with the relentlessness of a bounty hunter."

I wondered as I read Jon's response if he was aware that French author, photographer and film director Chris Marker is very active in Second Life. Perhaps there are two bounty hunters then? It is unlikely we'll ever know, given that Marker famously does not take interviews.

Jon Rafman: The Kool-Aid Man in Second Life project is partly an attempt to investigate certain 'outdated' concepts from bygone eras and to reframe them or test them out in distinctly contemporary pop-cultural contexts. I am interested in the disjuncture between earlier uses and my own use and what this reveals about how consciousness has changed over the past decades. Whether a fundamental change has occurred is an open question as the forms of alienation that existed one hundred years ago are present today in mutated forms. But these subtle changes are revealing of what it means to be alive today. What are these subtle changes I mention?

The fragmentation that started with the emergence of mass culture has only intensified. Decentralized global society is epitomized in the World Wide Web. This is not to say that the power of centralized authority has declined or that a new genuine techno-democracy has been achieved. This is far from the case; I’m interested in the ways that self-regulating authority manifests itself from the ground up.

I do think that the task of grasping the present clearly has become more difficult because so much now obscures us from seeing it. I frame my quest for the banal sublime as doomed from the beginning because I am trying to highlight the loss of a certain type of consciousness.

Am I nostalgic for Fin-du-Siècle Paris?:

Yes, my project is a somewhat melancholic attempt at pointing towards the importance of understanding the historical context in the digital age. I can’t deny my nostalgia for earlier modern periods; however I am also aware that the image of the past that I yearn for reveals less about the past and more about an acute lack that exists in the present. And it is this “lack” that I want to point towards.

A Conversation with Jon Rafman (NSFW video) - Bad at Sports

A conversation with Jon Rafman about Kool-Aid Man (in Second Life) - Martin, it's already now!

Is Second Life the theatre of the absurd? Ask Kool-Aid Man in SL - NPIRL

Selected Press:

Kino-Eye, the video cyborg - art:21org

Kool-Aid Man to Get It On With Avatar's Neytiri in 'Second Life' - Asylum

Best Link Ever! Guided Tours of Second Life with Kool-Aid Man - Art Fag City

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life (2009) - Rhizome

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life.com - asquare.org : Newtork Research

Kool-Aid Man in Second Life? OH YEAH! - An I'm not Lyng

Kool-Aid MAn is Giving NSFW Tours in Second Life [Wow, There's Still a Second Life?] - Boing Boing

Jon Rafman (Kool-Aid Man in Second Life) - Beautiful/Decay Magazine

Site Scavenging - Houston Press

Poke and Topiary Text Lead - The Great God Pan is Dead

You, the World and I, 2010

You, the World and I (.com)

When Orpheus’ beloved Eurydice dies, he cajoles his way

into the underworld with his musical charms and his lyre. Wanting her

but not her shade, he cannot forbear looking back to physically see her

and so loses her forever. In this modern day Orphean tale, an

anonymous narrator also desperately searches for a lost love. Rather

than the charms of the lyre, contemporary technological tools, Google

Street View and Google Earth, beckon as the pathway for our narrator to

regain memories and recapture traces of his lost love. In the film,

they are as captivating and enthralling as charming as any lyre in

retrieving the other: at first they might seem an open retort to critics

of new technology who bemoan the lack of the tangible presence of the

other in our interactions on the Internet.

Our narrator remembers that once, with her back turned

while facing the Adriatic Sea, a Google Street View car drove by and

took a picture of his beloved, who detested being photographed, without

her realizing it. Our narrator cherishes this photograph and the

entire relationship becomes encapsulated in the screen capture

replacing all other experiences and memories. Soon it is not

enough. Our narrator cannot imagine that, in a world where everything

is recorded, that someone could completely disappear. In daily

systematic searches for photographs of the nameless other, Google

Street View and Google Earth allow him to move seamlessly through vast

detailed three-dimensional space. This extraordinary geographical and

social exploration is favored by Google satellite images, user-created

3D renderings of Stonehenge and Machu Picchu and Street View panoramas

of favorite vacation spots. As an undifferentiated series of cultural,

historical and contemporary symbols float together or follow one

another in rapid succession, in a world where Dutch anthropologists

discover pre-Socratic fragments on Turkish islands, perhaps we come to

wonder as to the significance of anything and the place of tradition

and history itself. Unlike Orpheus, our narrator is not seeking for his

lost love but for photos of his love, he yearns for records of the

relationship not the woman herself or the relationship itself. In the

ultimate irony when he returns to the original photograph, it has been

removed. By getting as close to possible to the world through

technology, has our narrator not unwittingly distanced himself from

this world? But maybe even more than a doomed quest, does not this

whirlwind tour of an individual’s personal history and the world’s

cultural history, this modern tale of loss, retrieval and loss again,

expose that the change in our consciousness has preceded the change in

our technology?

“Wherever I go, there I am” is the old adage, be it

Yogi Berra or the Buddha. The detached gaze of a satellite image or an

automatic Street View camera confronts a human consciousness whose

ability to seek connectedness and meaning has already been compromised.

Contemporary technological tools simultaneously open and close vistas

on our inner and outer worlds.

New Age Demanded, ongoing

Woods of Arcady, 2010

BNPJ.exe (with Tabor Robak), 2010

Paint FX (R.I.P.), 2009

Deities & Demigods, 2011

New Age Demanded, 2010

Tokyo Color Drifter #1, 2009

DU3L, 2009

Sleeping Shepherd Boy .com, 2009

D-R-E-A-M-G-I-R-L .com, 2009

The Death of Google's First Server, 2008

The Horror The Horror .info, 2008

Portrait of a Net Artist as a Young Man .com, 2008

Forms of Melancholy, 2008

Thirty-Six Views of Ryugyong, 2008

Spam Fragments (pdf), 2008

LeWitt2 LeWitt3 LeWitt4 Hallway1 Hallway2, 2006

Unreliable Narrators , 2005

Documenting The "Vegas Of The Maghreb" Through Virtual Environments: Q&A With Jon Rafman And Rosa Aiello

Last night Jon Rafman held a lecture to inaugurate the second season of Palais de Tokyo’s “Imagine the Imaginary” exhibition. The Canadian artist, mostly known for his 9 eyes project, which utilizes the robotic eyes of Google Street View, has been an active artist on Second Life for the past five years, documenting his virtual peregrinations with movies like Kool-Aid man in Second Life.

For this exhibition, he made the video Remember Carthage (above), directed in collaboration with 3D animator Rosa Aiello. It continues his quest for the sublime in new landscapes, those of Second Life and of the video game Uncharted 3. It relays the story of a man looking for an abandoned hotel in the middle of the Sahara desert, and draws the viewer into the remains of the legendary city of Carthage while dealing with “the impact of a post-internet world on notions of national identity, physical traces of the past, and the issue of decline and nostalgia.”

We spoke with Rafman and Aiello about their collaborative work, the foreign nature of the past, and the importance of documenting virtual worlds.

The Creators Project: Can you please introduce your project for those who haven’t seen it yet?

Rosa Aiello: I like to describe it as a modern day experience of the uncanny, like a renewal of that trope with modern technology. We wanted to deal with the unconscious and this strange feeling you might have in real life, which is perfectly depicted in video games—seeing the same thing several times. It’s a very literary and overused idea of repetition, but with a new twist.

Jon Rafman: We came to this work through a process. At first, we wanted history to be the main subject of the movie, with a cyclic narrative—a little bit in the same way you surf through Wikipedia articles. While we were continually writing the scenario together, we arrived at this point in a pretty organic way. When looking very carefully at video games and virtual spaces, you notice several repetitions, looped movements, and the form of the footage really dictated the form the film took.

Aiello: It may have to do with the way video games are developed. Sometimes, your character is meant to be running, because he’s being chased or whatever, and you run through these spaces rather than look closely at them. Developers can easily repeat things without you noticing. We wanted to look at those aspects that people may not pay attention to.

What’s your opinion on the fact that the Palais de Tokyo chose to also exhibit your work in a physical space? Do you prefer the virtual platform?

Rafman: I like to put all of my films online because I don’t like the fact that so many art films are inaccessible, and that you can only watch them if you happen to be at the screening. For me the online aspect is not so much necessary, it’s just a great way to distribute the work. I think it would be best seen in a theater but I want it to be as accessible as possible. I didn’t think of it as an internet piece, I was thinking about film and literature, and majors works from artists like Chris Marker or W.G. Sebald.

Aiello: It didn’t ended up being something particularly historical in the end, but one of our first impulses was to make a certain part of history relevant again through artistic forms.

Don’t you think that if we simplify history through the prism of modern technologies, future generations might have a false image of what was really going on?

Rafman: We’re actually trying to criticize that danger. It’s true that things are going on at such an accelerated pace that we tend to forget ancient history, and our knowledge of it is sometimes limited to generalized articles on Wikipedia. I think the best films about the past highlight how foreign it is to us. While we were working on the movie, we asked ourselves what it would be like to go in a completely foreign land, a place you’ve never heard of before, and that you’ve never even imagined. There’s no place in the world that’s totally foreign anymore. Somehow, even if it’s through images or any kind of media, you never go somewhere and have your mind blown because you’ve never seen such a thing. The idea of foreignness has completely changed.

What advantages do you find in exploring the world through a virtual environment? I know that Jon said that what he liked best in Google Street View was to have the spontaneity of a robotic eye, free from human sensibility. What are the benefits of Second Life or games like Uncharted 3?

Rafman: What’s interesting is that this is a unique, completely human-constructed world becomes an exploration through consciousness, symbols, and desires. That’s why the repetitions become more interesting—because they’re purely human. We were watching The Adventures of Tintin yesterday, and it was actually an uncanny experience. The environments and the stages were actually the same as in our movie or the game we were looking at. At the beginning, there’s a museum, a ship, they crash a plane, go to an Eastern exotic place…they obviously picked these locations because they look so good when using 3D graphics. Perhaps we have a desire to construct something around those places. There’s a thing about the limitations of the 3D medium that dictates the content of games and movies.

Have you heard the story of that North American archeologist who thought she discovered pyramids through Google Earth?

Aiello: Ahah, that’s one of the drawbacks of technology, you might see things that are not actually there.

Rafman: Our memory is also affected by our interaction with technology and media of different kinds. When I visit places that I’ve already seen on Google Street View, I always have this weird feeling “I’ve been here before… on my Macbook Pro.”

Do you think it would be a good idea for schools to give internet courses so that future generations can fully understand the works of net artists?

Aiello: Well, it’s hard to tell what going to be relevant in the future and what platforms will remain. Second Life will probably be gone in the next 20 years, who knows? The original platform doesn’t even exist anymore. The point of making a film like that is to document a virtual world that might be destroyed and put it in a medium that can survive, like a video. There’s an historical dimension to document a virtual world.

Rafman: I think that this idea of internet archeology is pretty interesting, it’s important to recognize that digital things have a historical value too. In a way, they’re in the most precarious position because they can just disappear without leaving any trace whatsoever. It would be pretty egotistical for me to say that my work will be remembered—I’m not sure of what would be part of the history of the world. Anything digital is in a very precarious position. Archivists and historians do need to recognize these challenges.

Photos courtesy of Jon Rafman and Rosa Aiello.

For this exhibition, he made the video Remember Carthage (above), directed in collaboration with 3D animator Rosa Aiello. It continues his quest for the sublime in new landscapes, those of Second Life and of the video game Uncharted 3. It relays the story of a man looking for an abandoned hotel in the middle of the Sahara desert, and draws the viewer into the remains of the legendary city of Carthage while dealing with “the impact of a post-internet world on notions of national identity, physical traces of the past, and the issue of decline and nostalgia.”

We spoke with Rafman and Aiello about their collaborative work, the foreign nature of the past, and the importance of documenting virtual worlds.

The Creators Project: Can you please introduce your project for those who haven’t seen it yet?

Rosa Aiello: I like to describe it as a modern day experience of the uncanny, like a renewal of that trope with modern technology. We wanted to deal with the unconscious and this strange feeling you might have in real life, which is perfectly depicted in video games—seeing the same thing several times. It’s a very literary and overused idea of repetition, but with a new twist.

Jon Rafman: We came to this work through a process. At first, we wanted history to be the main subject of the movie, with a cyclic narrative—a little bit in the same way you surf through Wikipedia articles. While we were continually writing the scenario together, we arrived at this point in a pretty organic way. When looking very carefully at video games and virtual spaces, you notice several repetitions, looped movements, and the form of the footage really dictated the form the film took.

Aiello: It may have to do with the way video games are developed. Sometimes, your character is meant to be running, because he’s being chased or whatever, and you run through these spaces rather than look closely at them. Developers can easily repeat things without you noticing. We wanted to look at those aspects that people may not pay attention to.

What’s your opinion on the fact that the Palais de Tokyo chose to also exhibit your work in a physical space? Do you prefer the virtual platform?

Rafman: I like to put all of my films online because I don’t like the fact that so many art films are inaccessible, and that you can only watch them if you happen to be at the screening. For me the online aspect is not so much necessary, it’s just a great way to distribute the work. I think it would be best seen in a theater but I want it to be as accessible as possible. I didn’t think of it as an internet piece, I was thinking about film and literature, and majors works from artists like Chris Marker or W.G. Sebald.

Aiello: It didn’t ended up being something particularly historical in the end, but one of our first impulses was to make a certain part of history relevant again through artistic forms.

Don’t you think that if we simplify history through the prism of modern technologies, future generations might have a false image of what was really going on?

Rafman: We’re actually trying to criticize that danger. It’s true that things are going on at such an accelerated pace that we tend to forget ancient history, and our knowledge of it is sometimes limited to generalized articles on Wikipedia. I think the best films about the past highlight how foreign it is to us. While we were working on the movie, we asked ourselves what it would be like to go in a completely foreign land, a place you’ve never heard of before, and that you’ve never even imagined. There’s no place in the world that’s totally foreign anymore. Somehow, even if it’s through images or any kind of media, you never go somewhere and have your mind blown because you’ve never seen such a thing. The idea of foreignness has completely changed.

What advantages do you find in exploring the world through a virtual environment? I know that Jon said that what he liked best in Google Street View was to have the spontaneity of a robotic eye, free from human sensibility. What are the benefits of Second Life or games like Uncharted 3?