Pionir mađarskog eksperimentalnog filma.

Négy Bagatell:

Amerikai Anzix:

Narcisz és Psyché:

Narcisus and Psyche is based on a novel by Sandor

Weores which was adapted by Vilmos Csaplar and director Gabor Body for a

feature-length film. Borrowing the character of Psyche from mythology

and placing her in Europe in the 19th century, the authors give her a

"modern" life. She is an attractive young woman - and remains so

throughout the film, in spite of one hardship after another. Psyche is

libidinous, and her prurient interests shock her staid contemporaries.

For reasons that the viewer is left to ponder, her life is almost a

living punishment for her sexual laxity. Her child is taken away and

killed, and although she is in love with her tutor, who has syphillis,

she marries another man. She is suffering herself from some affliction,

which leads to hospital scenes that are acerbic commentaries on 19th c.

Western medicine. Psyche is about to leave for America with her husband,

when the story takes another abrupt turn.

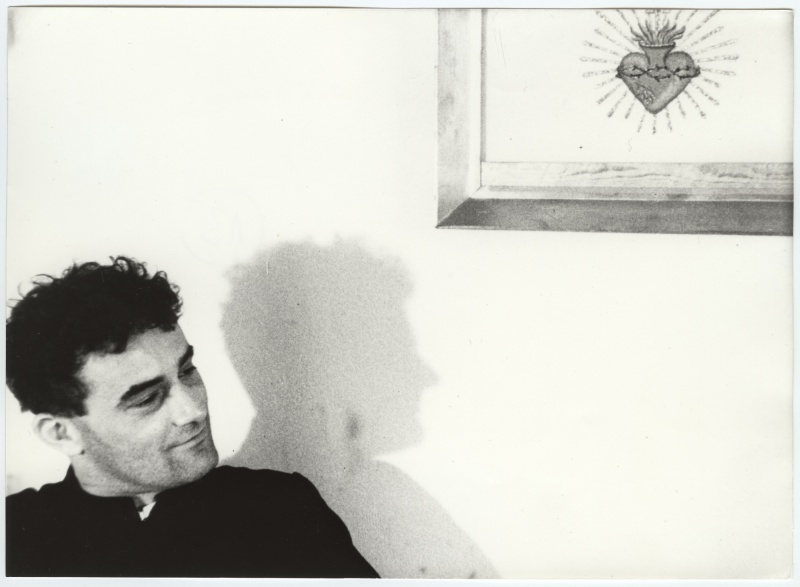

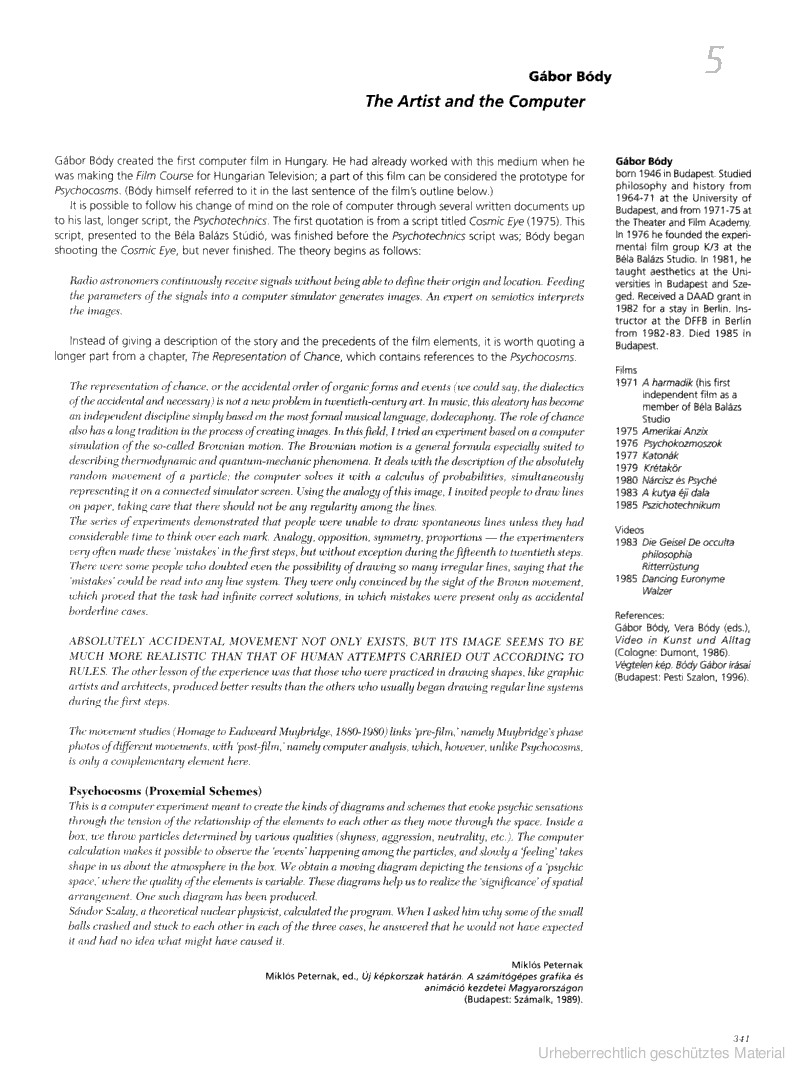

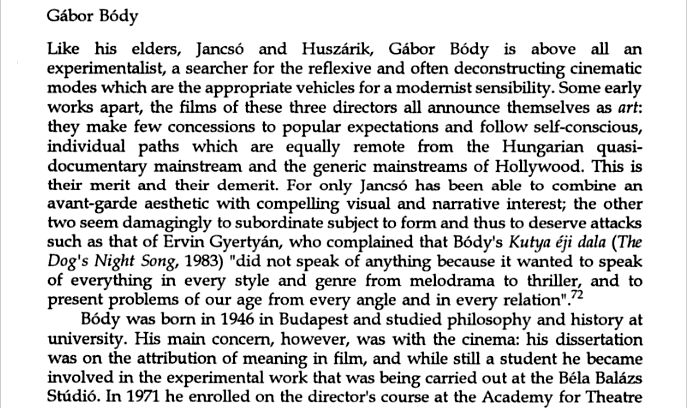

Born 1946 in Budapest. Hungarian film director, screenwriter, theoretic, and occasional actor. A pioneer of experimental filmmaking and film language, Bódy is one of the most important figures of Hungarian cinema.

Bódy was born in an urban middle-class family. He studied history and philosophy at Loránd Eötvös University and later filmmaking at the Academy for Theater and Film Arts. During his university days he became an influential member of the Béla Balázs Stúdió(BBS). He made his first film A Harmadik (The Third) (a documentary about students preparing an adaptation of Faust on stage) in 1971. He established various experimental and avantgarde projects at BBS including the Film Language Series in 1973 and the K/3 experimental film group in 1976, reshaping the postwar Hungarian avantgarde film's path.

In 1975 he completed his debut feature at BBS, which was also his graduation thesis film at the university. Amerikai Anzix(American Torso) won the Grand Prize for best new filmmaker at "International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg" and the Hungarian Film Critics prize for best first film. The film which decipts the lives of Hungarian 1848 Revolution veterans in the American Civil War features Bódy's experimentalism at the fullest. The whole film was re-edited using his own method called "light editing" in order to make it resemble a wracked silent film from the late 1800s.

His next feature Narcisz és Psyché was the largest-scale Hungarian production of its era. This epic production based on Sándor Weöres's poetic work Psyché starred Patricia Adriani, Udo Kier and György Cserhalmi and exists in three versions: an original 210min two part version, a 136min version for foreign distribution and a 270min three part television version.

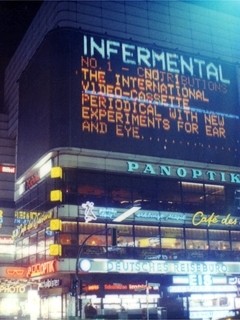

In 1980 Bódy began to work on the first international video magazine INFERMENTAL and managed to publish the first of 10 issues (plus one special issue) while on a residency at DAAD Berliner Küunstlerprogram in 1982. The series published featured a range of guest editors and in total included work from over 1500 artists from 36 countries and was published up to 1991.

After many frustrated projects Bódy managed to complete what was to become his final feature film Kutya éji dala (Dog's Night Song). Bódy cast himself as the lead in this ambitious and influential feature which incorporated Super8 and video footage as well as a range of Hungarian underground punk bands of the time in order to a film "deeply rooted in the fundamentals of today's reality."

In 1985 Bódy died under sketchy circumstances. A later published information (2001) hints his earlier collaboration (1973-1983) with the Hungarian Secret Police, the III/III. Authorities of the time (Hungary was then considered a 'satellite' country of the Soviet Union) stated that he had killed himself. His widow instead preferred a charge of murder against certain unidentified parties. No official investigation followed and Bódy's fate remains a mystery to this day.

Four Bagatelles (Négy Bagatell)

35mm, 28 min, 1975. Download (WEBM), Subtitles

Source: László Beke, Miklós Peternák (eds.), Gábor Bódy 1946-1985. A Presentation of his Work, Budapest: Mucsarnok, 1987. pp 90-91[edit]

- László Beke, Miklós Peternák (eds.), Bódy Gabór 1946-1985. A Presentation of his Work, Budapest: Mucsarnok, 1987 (English/Hungarian)

- Dan Kidner, George Clark and James Richards, A Detour Around Infermental, Southend-on-Sea: Focal Point Gallery, 2012.

- http://bodygabor.hu/

- Bio: http://www.bodygabor.hu/bio/?id=129

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%A1bor_B%C3%B3dy

- Bio: http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/artist/body/biography/

- http://www.ludwigmuseum.hu/site.php?inc=kiallitas&kiallitasId=291&menuId=10, http://issuu.com/ludwigmuseum/docs/body_gabor

- http://www.cinovid.org/person/2593

- http://newmedia-arts.net/cgi-bin/show-art.asp?LG=GBR&ID=A000000257&na=BODY&pna=GABOR&DOC=expo

- Exhibition in Berlin, 2011

Gábor Bódy, Hungarian form Bódy Gábor (born Aug. 30, 1946, Budapest, Hung.—died Oct. 24, 1985, Budapest), Hungarian film and video director. His often controversial ideas and methods of filmmaking met with critical success in Hungary and abroad.

In 1971 Bódy took a degree in philosophy from Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest; the title of his thesis was “

A film jelentése” (“The Meaning of Film”). From 1971 to 1975 he studied at the Academy of Drama and Film in Budapest. Meanwhile, he made experimental films at the Balázs Béla Studio, a haven for young filmmakers, including the film A harmadik (1971; “The Third One”). His graduation film, Az amerikai anzix (1975; “The Postcard from America”), won several prizes. In 1980 Bódy completed his avant-garde masterpiece, Nárcisz és Psyché (“Narcissus and Psyche”). Based on Hungarian poet Sándor Weöres’s Psyché (1972), an anthology of letters and poems by a fictional 19th-century female poet, the film is full of surrealistic elements, philosophical allusions, and visual experimentation, spanning centuries and shot in a number of different versions. The film attracted worldwide attention. Bódy was one of the founders of the international Infermental group, whose aim was to investigate the new opportunities offered by video art. His last feature film, Kutya éji dala (“Dog’s Night Song”), was completed in 1983. His death in 1985 was officially ruled a suicide. - www.britannica.com/

Gábor Bódy, «Infermental»

An infomagnetic space for living

Gábor Bódy

‘Infermental' was the first international videocassette magazine that published video artworks in part or whole, trailers, and reports (lasting 1-20 minutes) from around the world. Appearing annually with a total running time between four and six hours, each issue was compiled and edited in a different worldwide location. From the first issue (Berlin, 1982), which was publicized on a massive electronic billboard during the Berlin Film Festival and co-edited by Astrid Heibach and Gábor Bódy, who in 1980 initiated the ‘international recorded imagery project), to the last issue (Skopje and Osnabrück, 1991), a total of 660 works were gathered together. ‘Infermental' was conceived neither as festival nor gallery, but as a ‘running information memory' (Oliver Hirschbiegel) that bundled together excerpts, documents and events according to thematic and intellectual context.

Following the death of Gábor Bódy, his wife Vera Bódy was responsible for co-ordinating the project. The complete magazine archive has been on permanent loan to the collection of the ZKM Karlsruhe since 1992.

Gábor Bódy

‘Infermental' was the first international videocassette magazine that published video artworks in part or whole, trailers, and reports (lasting 1-20 minutes) from around the world. Appearing annually with a total running time between four and six hours, each issue was compiled and edited in a different worldwide location. From the first issue (Berlin, 1982), which was publicized on a massive electronic billboard during the Berlin Film Festival and co-edited by Astrid Heibach and Gábor Bódy, who in 1980 initiated the ‘international recorded imagery project), to the last issue (Skopje and Osnabrück, 1991), a total of 660 works were gathered together. ‘Infermental' was conceived neither as festival nor gallery, but as a ‘running information memory' (Oliver Hirschbiegel) that bundled together excerpts, documents and events according to thematic and intellectual context.

Following the death of Gábor Bódy, his wife Vera Bódy was responsible for co-ordinating the project. The complete magazine archive has been on permanent loan to the collection of the ZKM Karlsruhe since 1992.

Rudolf Frieling

Infermental 1

Berlin/West, Germany, 1982

37 contributions, 8 countries, 4 hours

37 contributions, 8 countries, 4 hours

Editors Gábor Bódy / Astrid Heibach

Supervisor Gusztáv Hámos

Supervisor Gusztáv Hámos

The first publication of INFERMENTAL-MAGAZINE today has hardly lost its zest and intensity. Perhaps we could do without a demonstration of experimental invention, a pure documentation of a performance, or the trailer of a feature film which only uses the pictures to illustrate a prefabricated world-view. But apart from the fact that the thinking continues to come from below, the trust in the power to copy from pictures (the tones, the “speech”) something which they have in common, something of their own (new) structure, remains fresh and inviting. The Odenbach and Bódy of 1978 are also expressive today, even more expressive than at the time of the “Conversation between East and West”. Because the movement of information and the fermentation that was generated by the INFERMENTAL-VIDEOS has in the mean – time gained energy the movement has long since gone beyond the magazine.

(Dietrich Kuhlbrodt)

(Dietrich Kuhlbrodt)

Infermental 2

Hamburg, Germany, 1982/83

77 contributions, 15 countries, 6 hours

77 contributions, 15 countries, 6 hours

Editors Oliver Hirschbiegel / Rotraut Pape

Supervisor Vera Bódy

Supervisor Vera Bódy

The editors of Infermental 2 placed immeasurable value in the interdisciplinary character of their edition. Proceeding on the idea that IF has no theology, follows no immediate goal, and that this leads to a maximum of flexibility in all directions our goal should be to compile an unpretentious encyclopedia of actual tendencies in all thinkable social areas.

Infermental should be open to all who use video as an artistic, or commercial information carrier, or who are willing, under special circumstances, to do so.

After looking through the material received, we took, accordingly, the liberty of shortening or only using excerpts, whereby the work was reduced to its essential message. Occasionally this brought about the discontent of some makers who mistook and mistake (even now) Infermental for an alternative festival. The edition should achieve, on the one hand, a half way value-free survey of the years production, and, on the other hand, awaken an intrest in the over-all picture. In this way initiating a pursuit of a particular content or along particular lines of thought. Everyone who wanted to know more about particular works or their authors, could through the editors intervention make the wished for contact. In this way the makers were provided the opportunity to present their work complete, unabbreviated and in an adequate framework.

(Oliver Hirschbiegel)

Infermental should be open to all who use video as an artistic, or commercial information carrier, or who are willing, under special circumstances, to do so.

After looking through the material received, we took, accordingly, the liberty of shortening or only using excerpts, whereby the work was reduced to its essential message. Occasionally this brought about the discontent of some makers who mistook and mistake (even now) Infermental for an alternative festival. The edition should achieve, on the one hand, a half way value-free survey of the years production, and, on the other hand, awaken an intrest in the over-all picture. In this way initiating a pursuit of a particular content or along particular lines of thought. Everyone who wanted to know more about particular works or their authors, could through the editors intervention make the wished for contact. In this way the makers were provided the opportunity to present their work complete, unabbreviated and in an adequate framework.

(Oliver Hirschbiegel)

Infermental 3

Budapest, Hungary, 1983/84

99 contributions, 18 countries, 6 hours

99 contributions, 18 countries, 6 hours

Editors Péter Forgács / László Beke

Co-editors Malgorzata Potocka / Peter Hutton / Egon Bunne

Supervisor Rotraut Pape

Production secretary Zoltán Bonta

Co-editors Malgorzata Potocka / Peter Hutton / Egon Bunne

Supervisor Rotraut Pape

Production secretary Zoltán Bonta

For us Hungarians the third issue of Infermental was of particular importance; for the first time the Hungarians, yes, in general, the eastern European artists took part in a larger number on a video undertaking of international scale. Naturally, in a land of middle technological development a video culture could only take place relative late, and even today we can only list 5-6 names that have access to video installations on a regular basis. That, finally, Infermental 3 could list among its 100 authors, 22 Hungarians, 5 Polish, 1 Rumanian and 1 Yugoslavian participant, is due to the principle of the video magazine which not only concerns itself with video art but also cinematographie in general (it also informs us about 35, 16 and 8mm films). We should also not loose track of the fact that the Budapest Béla Balázs film studio financed and organized the publication, furthermore, that the idea of Infermental was born in Hungary and that its founder and driving force was a Budapest film-maker, Gábor Bódy.

(László Beke)

(László Beke)

Infermental 4

Lyon, France, 1985

102 contributions, 14 countries, 7 hours

102 contributions, 14 countries, 7 hours

Editors FRIGO (Gérard Couty, Mike Hentz,

Christian Vanderborght)

Supervisor Astrid Heibach

Christian Vanderborght)

Supervisor Astrid Heibach

„You will never understand it if you don’t feel it“ is Frigos’s explanation of the term media-mystic and can at once stand as motto for the entire issue.

It was always a concern of INFERMENTAL’s to make correlations clear and to show new tendencies. The task of putting things together in order to make a statement must be achieved by every magazine regardless of the medium. A magazine on video tape has it, in this respect, more difficult, because of the sequential nature of the medium, than a printed magazine which may be read from front to back or this way and that. According to the technical possibilities and showing practices to date, the magazine on video tape dictates the interrelations between the contributions far more clearly to the viewer – at least as long as the wish of the initiator of INFERMENTAL, Gábor Bódy, is not reality: that is not 6 or 7 U-matic video cassettes shown one after the other to the public rather a video-disc for home use which allows every title to be chosen; comparable to having an encyclopedia on your bookshelf. How distant, unfortunately, this dream remains is evidence in the just as sudden (at least in Europe) vanishing appearance of the medium video-disc.

(Dieter Daniels)

It was always a concern of INFERMENTAL’s to make correlations clear and to show new tendencies. The task of putting things together in order to make a statement must be achieved by every magazine regardless of the medium. A magazine on video tape has it, in this respect, more difficult, because of the sequential nature of the medium, than a printed magazine which may be read from front to back or this way and that. According to the technical possibilities and showing practices to date, the magazine on video tape dictates the interrelations between the contributions far more clearly to the viewer – at least as long as the wish of the initiator of INFERMENTAL, Gábor Bódy, is not reality: that is not 6 or 7 U-matic video cassettes shown one after the other to the public rather a video-disc for home use which allows every title to be chosen; comparable to having an encyclopedia on your bookshelf. How distant, unfortunately, this dream remains is evidence in the just as sudden (at least in Europe) vanishing appearance of the medium video-disc.

(Dieter Daniels)

Infermental 5

Rotterdam, Netherlands, 1986

39 contributions, 13 countries, 5 hours

39 contributions, 13 countries, 5 hours

Editors Leonie Bodeving / Rob Perrée /

Schouten, Lydia

Supervisor Egon Bunne

Schouten, Lydia

Supervisor Egon Bunne

Infermental 5 is the Dutch edition of the first international magazine produced on a video cassette. It consists of five tapes, each one is one hour long; and on these tapes a collection of recent works by approximately forty artists from twelve different countries is represented. The works are reproduced in their totality.

We have chosen to set it up thematically, because we believe that the ‘magazine’ will be made more accessible this way. In addition, we hope, in this way, to give the viewer the chance to choose what he or she wants to see in accordance with his or her interest for specific subjects.

Our final selection has been based upon this thematic set-up, but was especially determined by the quality of the works which were submitted.

(Rob Peree)

We have chosen to set it up thematically, because we believe that the ‘magazine’ will be made more accessible this way. In addition, we hope, in this way, to give the viewer the chance to choose what he or she wants to see in accordance with his or her interest for specific subjects.

Our final selection has been based upon this thematic set-up, but was especially determined by the quality of the works which were submitted.

(Rob Peree)

Infermental 6

Vancouver, Canada, 1987

59 contributions, 25 countries, 6 hours

59 contributions, 25 countries, 6 hours

Editors Vera Bódy / Hank Bull

Supervisor Gérard Couty

Supervisor Gérard Couty

This is the first edition of Infermental to be produced outside Europe. The intention from the beginning was to make it the most international survey to date. We wanted to make a video map of the world. Not a map to draw national borderlines, but one to chart personal mythologies, poetics, and the response to mass media and computers. The editors would accept the terrain as they found it and fit the fragments together like pieces of a puzzle in the search to discover new relationships, tendencies, perhaps new ways of thinking.

We sent out 3,000 invitations and received over 300 replies, enough to produce three editions! As we viewed all these tapes we established very open, subjective contexts. These contexts act as prisms for splitting and diffracting ideas into different groups. Their names relate directly to the tactile sense of video. You will get a better sense of them from looking as the tapes than from reading about them in this book.

(Hank Bull)

We sent out 3,000 invitations and received over 300 replies, enough to produce three editions! As we viewed all these tapes we established very open, subjective contexts. These contexts act as prisms for splitting and diffracting ideas into different groups. Their names relate directly to the tactile sense of video. You will get a better sense of them from looking as the tapes than from reading about them in this book.

(Hank Bull)

Infermental 7

Buffalo, USA, 1988

58 contributions, 17 countries, 5 hours

58 contributions, 17 countries, 5 hours

Editors Chris Hill / Tony Conrad / Peter Weibel

Supervisor Rotraut Pape

Supervisor Rotraut Pape

As an internationally solicited project, Infermental affords its editors the opportunity to review at one time an unusually broad range of work. As a juror encountering such a field, I found myself caught up with issues concerning the tapes’ various modes of address. I was curious as to whether we would find a broad menu of video “dialects” or rather be impressed by some predictable and legible gestures, suggesting perhaps a widespread engagement with a particular art discourse or a desire for visibility to a specific audience. Perhaps modes of address is presently an American cultural preoccupation, with the clamor of many markets aggressively demanding our attentions within our commodity-driven lives. But more and more it seems that video artists do have the gamble the inspiration, production and reception of their work in a field that demands their weighing of the resources (tools and audiences) offered by a confidently established television industry against a less centralized art and / or alternative cultural or infoemotional scene.

(Chris Hill)

(Chris Hill)

Infermental 8

Tokyo, Japan, 1988

73 contributions, 15 countries, 5 hours

73 contributions, 15 countries, 5 hours

Editors Keiko Sei / Alfred Birnbaum

Supervisor Mike Hentz / Hank Bull

Supervisor Mike Hentz / Hank Bull

In the Afterglow of TV-Land

For this, the first Japanese edition, we’re chosen to focus on television culture via five themes, comic to critical, literal to metaphonic. Five channels of discourse. Bringing Infermental to Japan, islands far removed from the European and American continents of previous editions, yet very central to the global “info-magnetic” environment, we recognized the need to bridge a broader span than ever before. Not just East to West, but also from art to more popular expressions.

(Alfred Birnbaum)

For this, the first Japanese edition, we’re chosen to focus on television culture via five themes, comic to critical, literal to metaphonic. Five channels of discourse. Bringing Infermental to Japan, islands far removed from the European and American continents of previous editions, yet very central to the global “info-magnetic” environment, we recognized the need to bridge a broader span than ever before. Not just East to West, but also from art to more popular expressions.

(Alfred Birnbaum)

Infermental 9

Wien, Austria, 1989

45 contributions, 15 countries, 5 hours

45 contributions, 15 countries, 5 hours

Editors Ilse Gassinger / Graf + ZYX

Supervisor Chris Hill

Supervisor Chris Hill

We have arranged a program of sights for you, in which – like in Vienese cuisine – the West blends with the East, so as to create an unforgettable experience. Follow us to the select locations of Infermental 9. Our first meeting place, the “Technology Museum” with its Models and Constructions, introduces you to the polymorphous world of media art. We will then continue our tour with a visit of the “Freud Museum” and afterwards discuss, over a Cocktail of the senses in a Viennese café, travesty and visual pleasure. On “Heldenplatz” we have planted some Explosives in the hand baggage, people love to get excited in Vienna. Get your own personal souvenir from the former empirial residence: from the “Giant Wheel in the Snow” to a “Wedding in the Snow” a piece from home, both pastiche and parody.

The final chord or our guided tour is played by the siren sounds of a heavyweight tango, metamorphoses of the imaginary, a dance on the edge of a volcano. Surrender to the charm. There’s more to Vienna. Make time for it.

(Ilse Gassinger)

Catalogue and all videos [small format [176x128 pixels]]

The final chord or our guided tour is played by the siren sounds of a heavyweight tango, metamorphoses of the imaginary, a dance on the edge of a volcano. Surrender to the charm. There’s more to Vienna. Make time for it.

(Ilse Gassinger)

Catalogue and all videos [small format [176x128 pixels]]

Infermental 10

Osnabrück / Skopje, Germany / Yugoslavia, 1991

51 contributions, 16 countries, 6 hours

51 contributions, 16 countries, 6 hours

Editors Heiko Daxl / Evgenija Dimitrieva

Supervisor Keiko Sei

Supervisor Keiko Sei

Infermental tries to remove walls,

to pass over thresholds,

to combine the heterogeneousness with the own

and shows

HERE as BETWEEN the THERE,

is media (bridge) BETWEEN HERE and THERE,

shows HERE and THERE the BETWEEN...

to pass over thresholds,

to combine the heterogeneousness with the own

and shows

HERE as BETWEEN the THERE,

is media (bridge) BETWEEN HERE and THERE,

shows HERE and THERE the BETWEEN...

This tenth edition sets the preliminary finish of a

ten-year history of INFERMENTAL and

the international experimentalfilm workshop, Osnabrück.

INFERMENTAL, born as an idea BETWEEN

Hungary and Poland, is continued after 9 editions from

different cities in the world as an edition BETWEEN two countries:

Yugoslavia and Germany.

Two countries, both in a stage of

BETWEEN HERE and THERE:

Yugoslavia BETWEEN Orient and Occident,

Germany BETWEEN East and West,

Yugoslavia BETWEEN an old and (several?) new states,

Germany BETWEEN two old and one new state.

INFERMENTAL is BETWEEN both countries:

one editor from Germany, one from Yugoslavia.

(Heiko Daxl, May 1991)

ten-year history of INFERMENTAL and

the international experimentalfilm workshop, Osnabrück.

INFERMENTAL, born as an idea BETWEEN

Hungary and Poland, is continued after 9 editions from

different cities in the world as an edition BETWEEN two countries:

Yugoslavia and Germany.

Two countries, both in a stage of

BETWEEN HERE and THERE:

Yugoslavia BETWEEN Orient and Occident,

Germany BETWEEN East and West,

Yugoslavia BETWEEN an old and (several?) new states,

Germany BETWEEN two old and one new state.

INFERMENTAL is BETWEEN both countries:

one editor from Germany, one from Yugoslavia.

(Heiko Daxl, May 1991)

“Can you stand this?”

I heard this sentence in one of the tapes.

If art had ever been reasonable, art would never exist.

If reality does not exist, moving images

would never touch us.

THERE – BETWEEN – HERE-

For You who is reading this, it might be a very simple,

maybe a reasonable title.

But what does it mean for me HERE? Feeling the difference BETWEEN

all those 6 Billion people THERE

in this, our terra lingua, terra ars, terra full of racism,

disasters, injustice, violence and negations.

But this the world, we are living in.

This artificial world says Thank You for seeing us

and absorbes our true images.

(Evgenija Dimitrieva, May 1991)

The war on the Balkan 1991/92 tells its own story

but on the other side

another wall

and on the other side

of the other side

another one

another wall

and on the other side

of the other side

another one

www.infermental.de/documentsinhalt.htm#infermental4

Lecture held by Vera Body on June 3rd 1986 at ‘Städtisches Museum Abteiberg’, Mönchengladbach (Germany)

[...] Since the beginning of the 60s Name June Paik’s and Wolf Vostell’s electronic images have caused the birth of a new genre: VIDEO. Its decisive charcteristics in contrast to other art forms - such as painting, photography, film and theatre – were clarified into the following three functions not long after by Wulf Herzogenrath:

1. the immedeate control of the image

2. the manifold electronical possibilities

3. the reproduction of the image on the monitor.

As a vital element I would add the perception of Jean-François Lyotard. He states that with video we have images ‘which, contrary to the tradition of photography and cinema, and also contrary to a large part of painting, are only produced and not reproduced. To find something equivalent in painting, one would have to look in the direction of abstract painting which is not – simply said – a reproduced image. In this way what is known, seen and heard is nowadays being less known, seen and heard. Machines bring forth facts which by far surpass our sensous adaptability.’

In the 60s and 70s video was increasingly employed as an artist means by musicians, performance artists and other artists. The discovery of video as a mirror, as a possibility of self-portrayal, of the audience’s potential participation in the events (as in works by Joan Jonas, Peter Campus, Frank Gillette, Dan Graham and others) created the effortless realization of synchonization between reality and its presentation. Live enviroments made possible through ‘closed circuits’ (Nam June Paik: Video-Buddha, Bruce Nauman: Video-corridor, or Peter Campus: Interface and others) and the electronic experiments of Fluxus which hoped to break the pseudo-transperancy of the medium television (René Berger) shaped the early stage of video art. Douglas Davis described the artistic video of the 70s as anti-television. Media ideologies from Walter Benjamin (photography), Bert Brecht (radio), and Marshall McLuhan (TV-electronic age) provided the intellectual background of the new electronic art. The esoteric atmosphere of the galleries representing the minimal-concept art and video art in the 70s cultivated the individual mythology of their artists, but could not become a CULT programme for a broad public even after initial effort. The early medium-exploring age of video art (David Antin), which a short time later was to be quoted as a boring epoch, met with a crisis at the end of the 70s. Only a few collectors and some institutes were interested in the new art form. Outstanding characteristics, such as personal participation in events (mirror effect), the semiotic use of objects (Minimal ART) and the intimate approach to the medium survived the descent.

Facing the fact that installatios in every documenta, Biennale in Venice or the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam continued in the 80s, the individual product of a video cassette is becoming more and more significant. Considering the worldwide epidemic of video festivals (Tokio, Locarno, Montbéliard, Toronto, Kijkhuis-Den Haag, San Francisco, Montreal, Rio de Janeiro, Marl, Salsomaggiore etc.) which have not only increasingly been connected with awards, but also with the presence of representatives of public and private television, there is no doubt that broad change in form and content of video in the 80s can be concluded. Moreover, Video/Book projects (Infermental/LichtBlick) are aiming at breaking the traditionally limited circle of the video marktet.

As a circulating record of information (Oliver Hirschbiegel), the video cassette became a quickly available carrier for interdisciplinary works and the first international magazine on video cassettes INFERMENTAL originated in 1980 with the ambition to collect and reorganise all new directions of the electronic art. New genres and trends became perceptible in this info – magnetic ‘lebensraum’ (Gábor Bódy).

On the occasion of his exhibition ‘The Immaterials’ at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in the spring of 1985 Jean-François Lyotard requested that the encyclopedia of ours be electronic. I am not claiming that INFERMENTAL is already as far as this, but the objectives and methods we have been working with since 1980 are going in this direction. According to the concept of INFERMENTAL the annually changing panels of editors endeavour – from the presented material – to crystallize categories corresponding to the context through which the various genres like New Narrativity or Electronic Painting develop. [...]

The recent exhibition at Focal Point Gallery in Southend-on-Sea was the first UK gallery showing of Gábor Bódy’s extraordinary ‘video-cassette magazine’ project, INFERMENTAL (1981–91). A magazine about video produced on video-cassettes, INFERMENTAL spanned ten years and 11 editions, each of which comprised between 50 and 100 contributions, or around four to seven hours. Each issue was guest-edited by different artists, and the project aimed – like a portable festival or live magazine – to present the ‘new’ in film and video that year or the exploration of a chosen topic. Though it billed itself as a magazine, INFERMENTAL was close to a fanzine in ethos and style: egalitarian, informal (many of its editors took the liberty of cutting down the works shown) and invested in the idea of distribution rather than uniqueness.

Bódy, a Hungarian video artist and filmmaker, conceived of the project as a means to build an ‘Encyclopaedia of Recorded Imagery’, and INFERMENTAL forms part of his belief in the universalist potential of video and television to provide a forum for shared discussion across different countries and contexts. The first edition, edited by Bódy and artist Astrid Heibach and produced in 1982, addressed the theme of East and West. Indeed, over the years the project grew from a Western European project to one with an international scope, with editions being produced in Vancouver, Tokyo and Buffalo in upstate New York. The magazines were sold or hired out to institutions at a time when video art had limited acceptance or distribution in film festivals and, to a lesser extent, museums. Most importantly, INFERMENTAL’s actual form took part in the rhetoric of immediacy and universality surrounding video art at the time: the format allowed a convergence between documentation of new work and its actual presentation – rather than the presentation of work through the sorry words and stills you have here – that mimicked the synthesis of reality and its presentation, and of instantaneous playback, that video afforded.

At Focal Point, curators George Clark and Dan Kidner showed four issues – INFERMENTAL #1 (Berlin, 1982), #4 (Lyon, 1985), #8 (Tokyo, 1988) and a special feature on ‘Cross-Cultural Television’ (1987) – in structures designed by the London-based artist James Richards. As is often the case in Richards’ work, there was in these viewing platforms a tension between private and public, in that the structure’s function as a viewing platform was hidden from general view. The platforms provided mediation between what could have been a problematic exhibition of work which had been intended as a collective social experience, as to watch the videos one is forced to climb onto the platforms and sit, or to enter a small constructed room, re-creating a private-sphere experience while remaining within the public gallery.

The material is absorbing as a historical document, both for its inclusion of well-known figures – such as Joan Jonas, Ute Meta Bauer and Tony Oursler – and for the host of contributors whose names have dropped off survey indexes. What are understood to be core concerns of video in the 1980s – semiotics, identity, sexual politics – are here in full measure, but there are also more surprising finds, such as Ute Aurand’s beautiful Silently Absorbed in Conversation (1981), shown on INFERMENTAL #1, which calls to mind Maya Deren’s later work.

A key argument of the exhibition was the possibility of looking at INFERMENTAL as a technological ‘what if’: it was a collectively organized UbuWeb before its time, a user-generated magazine that went to lengths to document and internationally distribute – something that is now so simple to do on the Internet. Focal Point’s well-judged exhibition of the project, which framed INFERMENTAL explicitly as ‘a historical archive and a live project’, not only mapped the contents of the magazines but also retrospectively highlighted the changing fortunes of video exhibition, distribution and rhetoric in the face of other technological innovations since.

Bódy, a Hungarian video artist and filmmaker, conceived of the project as a means to build an ‘Encyclopaedia of Recorded Imagery’, and INFERMENTAL forms part of his belief in the universalist potential of video and television to provide a forum for shared discussion across different countries and contexts. The first edition, edited by Bódy and artist Astrid Heibach and produced in 1982, addressed the theme of East and West. Indeed, over the years the project grew from a Western European project to one with an international scope, with editions being produced in Vancouver, Tokyo and Buffalo in upstate New York. The magazines were sold or hired out to institutions at a time when video art had limited acceptance or distribution in film festivals and, to a lesser extent, museums. Most importantly, INFERMENTAL’s actual form took part in the rhetoric of immediacy and universality surrounding video art at the time: the format allowed a convergence between documentation of new work and its actual presentation – rather than the presentation of work through the sorry words and stills you have here – that mimicked the synthesis of reality and its presentation, and of instantaneous playback, that video afforded.

At Focal Point, curators George Clark and Dan Kidner showed four issues – INFERMENTAL #1 (Berlin, 1982), #4 (Lyon, 1985), #8 (Tokyo, 1988) and a special feature on ‘Cross-Cultural Television’ (1987) – in structures designed by the London-based artist James Richards. As is often the case in Richards’ work, there was in these viewing platforms a tension between private and public, in that the structure’s function as a viewing platform was hidden from general view. The platforms provided mediation between what could have been a problematic exhibition of work which had been intended as a collective social experience, as to watch the videos one is forced to climb onto the platforms and sit, or to enter a small constructed room, re-creating a private-sphere experience while remaining within the public gallery.

The material is absorbing as a historical document, both for its inclusion of well-known figures – such as Joan Jonas, Ute Meta Bauer and Tony Oursler – and for the host of contributors whose names have dropped off survey indexes. What are understood to be core concerns of video in the 1980s – semiotics, identity, sexual politics – are here in full measure, but there are also more surprising finds, such as Ute Aurand’s beautiful Silently Absorbed in Conversation (1981), shown on INFERMENTAL #1, which calls to mind Maya Deren’s later work.

A key argument of the exhibition was the possibility of looking at INFERMENTAL as a technological ‘what if’: it was a collectively organized UbuWeb before its time, a user-generated magazine that went to lengths to document and internationally distribute – something that is now so simple to do on the Internet. Focal Point’s well-judged exhibition of the project, which framed INFERMENTAL explicitly as ‘a historical archive and a live project’, not only mapped the contents of the magazines but also retrospectively highlighted the changing fortunes of video exhibition, distribution and rhetoric in the face of other technological innovations since.

Melissa Gronlund

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar