Češki fluxus-velikan.

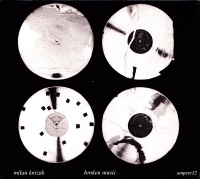

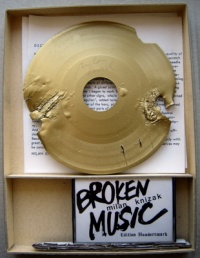

Lomio je gramofonske ploče i ponovno sljepljivao komadiće, pržio ih i bojao. Tako je stvarao fizičke kolaže slomljene muzike.

artlist.cz/?id=526

monoskop.org/Milan_Kn%C3%AD%C5%BE%C3%A1k

01 Broken Music (28:35)

02 Broken Music (32:04)

Total time 60:39

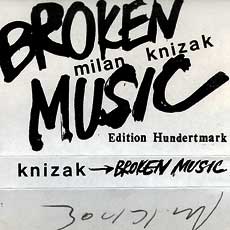

K7 in special packaging + inserts, Edition Hundertmark, Cologne. Germany, 1983

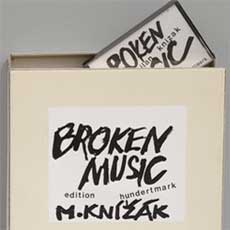

Issued by Armin Hundertmark publisher, a Cologne imprint specialized in artist books and multiples (now relocated in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria), who also published a few cassettes by Henri Chopin, Philip Corner, Henry Flynt or Hermann Nitsch. This limited edition of 40 signed copies of Czech artist Milan Knížák‘s ‘Broken Music’ is an artist multiple including a melted record, one cassette and various texts in a special 27.1 x 21 cm box. One copy is at the MoMA, NY, an other in our reader Rainier’s own collection and he generously offered a rip (thanks!). The music comes from damaged LP recordings, with a few ralentandos and speed changes by the artist here and there. The discs used by Knížák are probably similar to the ones pictured above, especially the 4-pieces glued together. The result is different from the monotonous 1979 LP of the same name (unauthorized CD reissue, Ampersand, 2002). This one is varied and Knížák is actually playing and composing with the LPs. An overview of Knížák’s visual work is available here. An introduction to Knížák’s music is offered here (with sound files). The primary source of information on Knížák’s music is Petr Ferenc’s 2003 article ‘Milan Knížák the musician’.

Download

Discography:

- 1979 ‘Broken Music’, LP, ed. Multhipla Records (aka Cramps Records), Milan, Italy

- 1983 ‘Broken Music’, cassette and inserts, Edtion Hundertmark, Cologne, Germany

- 1989 ‘Broken Music – Details’, flexi disc, by the Arditti String Quartet, DAAD galerie, Berlin, Germany

- 1991 ‘Obrad Horící Mysli’, 2xLP, Condor, CZ

- 2002 ‘Navrhuju Krysy’, CD, Anne Records, CZ

- 2002 ‘Broken Music’, CD, Ampersand, USA (1979 Multhipla Records LP reissue)

- 2005 ‘Broken Music’, CD, Kissing Spell, UK (1979 Multhipla Records LP reissue)

- 2008 ‘Broken Tracks’, CD, Guerilla Records, CZ

- 1996 ‘Graficke partitury a koncepty’ [Graphic Scores and Concepts], book+CD, Petr Kofron and Martin Smolka ed., Agon Orchestra (contains the 1973 conceptual music piece ‘nl’)

- 1965 ‘Aktual Kommunity’, samizdat LP, CZ

- 198? ‘Attentat Na Kulturu’, 1971-2 live recordings, cassette, S.T.C.V. (aka Petr Cibulka), CZ

- 2003 ‘Attentat Na Kulturu’, CD, Anne Records, CZ

- 2005 ‘Deti bolševizmu’, CD, Guerilla Records, CZ

UbuWeb:

Broken Music (1983)

Total time 60:39

K7 in special packaging + inserts, Edition Hundertmark, Cologne. Germany, 1983

Issued by Armin Hundertmark publisher, a Cologne imprint specialized in artist books and multiples (now relocated in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria), who also published a few cassettes by Henri Chopin, Philip Corner, Henry Flynt or Hermann Nitsch. This limited edition of 40 signed copies of Czech artist Milan Knížák. Broken Music is an artist multiple including a melted record, one cassette and various texts in a special 27.1 x 21 cm box. The music comes from damagedLP recordings, with a few ralentandos and speed changes by the artist here and there. The discs used by Knížák are probably similar to the ones pictured above, especially the 4-pieces glued together. The result is different from the monotonous 1979 LP of the same name (unauthorized CD reissue, Ampersand, 2002). This one is varied and Knížák is actually playing and composing with the LPs. The primary source of information on Knížák's music is Petr Ferencís 2003 article: Milan Knížák the Musician. -- Continuo

Various Tracks

Recorded at Radio Vienna, Austria, 1990

instruments:

- 2 records players playing my destroyed music

- 2 taperecorders with tapes of my older pieces

- 2 synthesizers played by myself

- piano & voice also by myself

(Milan Knizak)

From Fluxus Anthology Box, 30th Anniversary

From Fluxus Anthology

RELATED RESOURCES:

Milan Knížák

1940, born in Pilsen, Czechia

Lives in Prague

Lives in Prague

Initially, Knížák wanted to be a painter, but broke off a study of art in 1962. That year, he also produced his first environments in streets and courtyards. Together with Jan Mach, Vít Mach, Sonia Švecová, Jan Trtílek and Robert Wittmann, he founded the group Aktuální umění (Actual Art), which removed the word “art” from its name in 1966 and was known as Aktual from then on. Aktual staged numerous actions that involved a chance audience, e.g. A Walk around Novy Svět (New World) and the Demonstration for Oneself (both 1964). Besides their actions, the group published small editions of handbills, samizdat magazines and objects. Aktual proclaimed a complete union of art and life and focused its interest on man, his actions and awakening people’s awareness.

Milan Knížák’s contact to Fluxus came about in 1965 through the mediation of the Czech critic Jindřich Chalupecký. Knížák was soon promoted to “Director Fluxus East” by Maciunas – and this although his attitude to Fluxus remained critical, since he found many actions and their setting in a classical stage context artificial. In October 1966, Knížák organised the Fluxus concert in Prague, in which he appeared together with Ben Vautier, Jeff Berner, Serge Oldenbourg, Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles. George Maciunas already invited Knížák to the USA in 1965, but it was not until 1968 that he managed to obtain a visa. In New York, he participated in the Fluxus events taking place there; in New Brunswick he realised his Lying Ceremony and in New York the Difficult Ceremony. Maciunas prepared the publication of Knížák’s collected works as a Fluxus Edition, but they never actually appeared.

In 1970, Knížák returned to Czechoslovakia. Always under police surveillance, and he was also arrested on occasion. He received a fellowship from the DAAD Artists’ Programme and came to Berlin in 1979, after which he was frequently represented at exhibitions in Germany. Since 1990, Knížák has been teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, and has been director of the National Gallery in Prague since 1999.

http://www.fluxus-east.eu/index.php?item=exhib&lang=en&sub=knizakArtist and musician associated with Fluxus, organiser of the first Happenings in Czechoslovakia. Born 1940 in Plzeň.

- Aktual

- Broken Music

- Fluxus

- 1970s-80s

- After the Revolution

Works

Broken Music

"In 1963–64 I started playing records either at slow speed or at high speed and, in so doing changing the quality of the music, creating my own other music.

In 1965 I began destroying records: scratching them, puncturing them, breaking them. Playing them – which ruined the needles and sometimes the whole record player – created a whole new type of music, one that was surprising, jarring, aggressive and funny. Songs could last for just a brief moment or, if the needle got stuck in a deep scratch, practically forever, the same passage playing over and over.

I developed this method even further. I started gluing records together, painting them, burning them, cutting and pasting parts of different records together and so on, in order to achieve the greatest variety of sounds. Later I began working in the same way with complete scores. I deleted some notes, keys and other symbols, or entire bars (in this way dictating the rhythm), redrew the notes and keys, changed the tempo, and the like. I also changed the sequence of the bars, played compositions in reverse, turned whole rows upside down, pasted together the most diverse parts of various scores, and so on.

I also used collections of popular songs or other pieces as scores for orchestral compositions. Each instrument or section or group plays one song. The resulting sound, where everyone keeps the tempo, intonation and length of the particular piece that they are playing, creates a new symphony.

And of course there were other similar approaches, combinations and offshoots. Since music created from playing destroyed records cannot be written down in notes or in other language (or only with great difficulty), the records themselves can also be considered as the notation." (from Milan Knížák, Novy Raj, Selection of works 1952-1995, Prague: Galerie Mánes, 1996; translated from Czech by Andre Swoboda) more (in Czech)

Broken Music (1979)

Composition No. 1, 18'56" OGG

Composition No. 2, 3'27" OGG

Composition No. 3, 4'25" OGG

Composition No. 4, 10'23" OGG

Composition No. 5, 13'52" OGG

Originally released in 1979 on Multhipla Records.

Reissue released on Ampersand – ampere12, CD, 2002

Curated and Assembled By – Walter Marchetti

Reissue Direction – Dawson Prater

Edited at Harpo's Bazaar (Bologna, Italy)

via Direct Waves blog

Broken Music (1983)

Untitled (Side A), 28'35" OGG

Untitled (Side B), 32'04" OGG

Label – Edition Hundertmark, 1983

Format – Carton box including a C-60 cassette of Knizak's Destroyed Music, signed and hand-numbered 1 to 40, a partially melted, hand-painted and signed 7" record, and 2 sheets of information text.

Cassette was also released separately in an edition of 60, signed but unnumbered copies.

via Continuo blog

Broken Music (1989)

Details, 28'35" OGG

Label – Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD, 1989

Format – Flexi-disc, Single Sided, 33 ⅓ RPM

via Continuo blog

Literature

- Jindřich Chalupecký, "Příběh Milana Knížáka", in Na hranicích umění. Několik příběhů, Prostor: Prague, 1990, pp 89-105. (Czech)

- Knížák's Fluxus event scores in The Fluxus Performance Workbook, edited by Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn, 1990/2002, pp 63-68.

- Milan Knížák, Actions For Which at Least Some Documentation Remains, Prague: Gallery, 2000.

- Tomáš Pospiszyl, Srovnávací Studie, Prague: Agite/Fra, 2005, pp 80-95. (Czech)

- Caleb Kelly, "Milan Knížák's Broken Music", in Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction, The MIT Press, 2009, pp 140-149.

- Claire Bishop, "I. Prague: From Actions to Ceremonies", in Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Verso Books, 2012, pp 131-140.

External links

- Home page

- Knížák at Artlist.cz

- Knížák at UbuWeb

- Knížák at abART

- Knížák at Fluxus East

- Knížák at Wikipedia

Info

I.

Milan Knížák is an artist whose activities extend into many spheres both inside and outside the art world. His artistic activities include events, fine art, music, architecture, design, fashion, poetry and photography. However, more important than the spheres in which he is active or the media he uses is the fact that he often works in several spheres at once, and that these spheres and media permeate each other and extend across the wide range of his activities.

The diversity and of his activities and the expressive devices he uses are the result of on the one hand his disposition, and on the other his conviction that life and art are deeply linked internally. This means that his art works are also perceived in association with his non-creative social activities. This social dimension is an organic part of his work, since Milan Knížák never wanted simply to create artefacts which would represent him.

Knížák’s creative career began in the 1960s. In his own words, this phase of his work represents an attempt to make of art an ars vivendi (c.f. for example the text of the action lecture Why That Way 1964). He attempts to bring art closer to everyday life and thus provide both art and life another dimension. He created Short Lived Street Exhibitions (1962-64) and various street environments. The emphasis Knížák placed on the totality of life and the connections between all aspects of life led him to look not only for new possibilities of presenting art, but new expressive positions and forms of artistic activity. In his events, art is not restricted only to the professional artist or a circle of experts. It does not only operate within the institutionalised context of a gallery, exhibition or concert hall, and not only for a selected party interested in advance, but enters life as it is lived. The encounter with an artwork is not a secondary, intellectually sensual pleasure, but a challenge to change our lives, i.e. to change our approach to life. (The new expressive forms Knížák uses, i.e. events, manifestations, demonstrations, etc. can also be included under the concept of art and extend the boundaries of what we mean by the word art, though at that time it was not important to Knížák if this was the case, since these new forms for him did not lose their instrumental purpose, i.e. they represented a training in life). This difficult and on a wider scale unrealisable programme, reflecting the overall mood of the 1960s, is the decisive axis of all his artistic and life endeavours. His attempt to incorporate events into the lives of their participants is an endeavour to incorporate art (in a corresponding form) into other life situations. It is the attempt to provoke its recipients to reflect, to discover in themselves the ability to leave behind customary social forms and conceptual stereotypes, and to learn to recognise and appreciate new experiences and to be open to the pleasure to be derived therefrom. Even though in the end the attempt to link art and everyday life cannot be achieved because of their constitutive differences (different methods of perceiving, experiencing and comprehending the contexts in which we find ourselves), the endeavour in itself extends art into other spheres, including multidisciplinary and even media spheres.

Active and conceptual moments alternate and pervade Knížák’s events, people are linked to the game and invited to allow the game to be played out in their own minds. After ambitious events in which several types of activity are linked (A Walk Around the New World 1964, 2nd Manifestation of Actual Art 1965, etc.), Milan Knížák decided to concentrate on a limited number of motifs. From events focussing on social links or a certain routine way of behaving, he began to concentrate on the personal experience of the individual. Events began to appear of a psycho-physical character (Lying Ceremony 1968), or for a restricted number of participants (Difficult Ceremony 1969), in which ritual elements are important (Stone Ceremony 1971). In these events Knížák reached the deeper, more primeval layers of human life and existence. In this respect it is significant that many of his events from the start of the 1970s are entitled ceremonies. In the 70s his events become calmer and their conceptual side deeper. In the latter half of that decade several events are relocated to the space of the mind (the space of the mind is his own term). Events become concepts, though this conceptual aspect is not their only characteristic: many events still relate to human physicality (e.g. Habitation 1979, Human 1979). By virtue of their dematerialisation several events focus on the space of the mind itself (e.g. Spaces 1982). Around this time conceptual mathematically conceived events make an appearance, e.g. Events 1977 or Mathematical Problems 1977. Another difference between his events of the 1960s and 70s is that in the early works it was possible to be drawn violently into events, but as soon as the actions of an event become the inner life, the basic meaning of the event has somehow to be grasped prior to its execution. He creates events focussing on the individual’s perception, e.g. Material Events 1977, Recognition 1977, as well as events such as Friendship with a Tree 1980. This last instance, though it does not exclude a certain community, is intended for participants who are already prepared to understand it. The events were so closely linked with Knížák’s life that this was not only a type of artistic activity, but (especially in the case of his early works) a way of life in itself. This demanding approach to an event is such an important condition for its realisation that it also functions as a natural limit. This was so, for instance, in the case of Event 1984 from 1984, which does not contain any instructions regarding how it is to be executed. It becomes a kind of specific reflection on events as such. Reflection on events comes at a time when the event was waning in Knížák’s work. However, giving up events did not mean simply transferring his activities into other spheres, since the decline of events is at the same time an expression of the concept and expressive significance which they have in the work and life of Milan Knížák. In a series of events entitled Paraphrases from 1989, Knížák returns to certain of his works from the 1960s and 70s. He returns to their subjects as though to topics which can be abstracted therefrom. Events which had been executed in real space with the full involvement of physicality (or were at least so intended), are now transferred in part or completely to the space of the mind. The suspense of the original events created by their incorporation into everyday life is not transposed to the suspense of mental structures. The set of events entitled Paraphrases shows how Milan Knížák deserted what were originally physically and materially executed events, which are no longer repeatable in respect of their physical and material intensity.

Knížák returns to pictures and painting after a relatively long silence in the latter half of the 1980s. More precisely, it was only then that he fully accepted the distinctive character of the image. Pictures from the 1960s, from the earliest phase of his work, which are not simply historical documents but are related to the whole of his output, date back to the cycle Portraits (1964). However, these pictures are so connected with other of Knížák’s activities (Short Lived Street Exhibitions, events) that they cannot be restricted only to the pictorial. Even in the 1970s Knížák used painting more as an instrument (c.f. the cycle Clothes Painted on the Body, or other paintings on textile, etc.), rather than a completely independent expressive means. It was only in the latter half of the 1980s that Knížák discovered painting as such. The result was a number of paintings discovering the medium and reacting to the postmodern paradigm. Sculptural elements appear in some pictures (e.g. Pictures Painted on POP 1989, etc). At the end of the 80s the artist begins painting on objects. It is worth remembering in this respect his early work such as Statue of a Table (1964), Statue of Trousers (1964), etc. The paintings on objects from the end of the 1980s are not conceptual so much as emotional, featuring expressive colour tones.

At the start of the 1990s, Knížák began to concentrate on sculpture. Craftsmanship and formal qualities acquire a predominant role. Previously he had not regarded the craftsmanship of his work as important and had almost wilfully neglected it. Now he emphasised it. However, this was not simply about a purely instrumental method of working. Purity of craftsmanship freed of random movement becomes, along with material perfection, a means of liberating the resulting form from excessive subjectivity and an immediate dependency on the materials. The perfection of the resulting shape, replacing the unrepeatability of the personal processing procedures of industrial production, allows for a greater focus on the artist’s own intention and draws attention indirectly to the more general contents of the work, so that artefacts becomes signs and symbols. The form of processing is now a reminder of Knížák’s conceptual endeavours. It is around this time that the series of works entitled New Paradise is created. This free cycle includes the graphic designs Illustrations to a New Bible 1990, Biblical Landscapes 1991, the installations New Paradise 1990-91, Mutants 1991, 1376-1382 1992, a series of drawings entitled BMC 1992-94, and the installation Barbie 1994-95. A series of masks entitled First Twelve 1991-92 and the installation Creatures and Slightly Gentler Creatures 1993-94 are processed in a similar way.

This overview of the development of Milan Knížák’s work examining individual creative periods and outlining the predominant expressive resources that belong to it, can only offer a partial view of his work. A more important character of Knížák’s creative method, though one which is difficult to put into words, is the interplay of his activities, the breadth of the activities which mutually influence each other, forming a variable and polymorphous background to his individual works.

II.

The next part of this text on Milan Knížák offers examples of his work in the spheres of architecture, music, fashion, jewellery design and production, furniture and interior design. The classification of these spheres of his work corresponds to that given in the first part of this text.

This means that even in this sphere of his oeuvre we can find links with external conditions (materials and social conditions, e.g. the possibility of working in a studio, sales possibilities, various forms of pressure from the authorities, etc.) and internal conditions (his personal development, the immanent development of a certain creative problem, etc.)

Certain accents characteristic of individual periods can be found in Knížák’s work. Certain works from the 1960s, e.g. Fork Building (1963-64), Destroyed Music (1965), Actual, Updated Clothing (1964), Clothes Painted on a Body (1965), Tearing Jewels (1962-70), Jewels for the Entire Body (1963-1964), relate to and supplement in many respects other of the artist’s activities of that time, above all his events. Action, a focus on the public and a certain non-artistry and personal commitment could characterise this early period of Knížák’s output.

At the end of the 1960s and during the 70s it was ceremonies and rituals which resulted from the artist’s demonstrations. In the 1970s, as a consequence of external circumstances, Knížák documented his activities during the 60s and developed and elaborated many themes of his works. The conceptual character of his output intensified. Thinking through certain principles resulted in marginal designs within the framework of the sphere in question. At that time Knížák was thinking about intangible architecture, which led him, for instance, to write the large text entitled An Attempt at a Non-systematic Introduction to the Problem of Intangible Architecture (1970-1985), from which this work includes the excerpt Game of Architecture (1974-1975). At the same time he was creating a comprehensive design for the City in a Desert (1969-72), which represents an architectonic-urban complex accompanied by a vision of a different society. Knížák created musical concepts and was reflecting on the boundaries of music, an activity which resulted, for instance, in Music as Architecture (1968-76). The compositions of this period, e.g. Suspected Imagined Music (1978) or Simple Buildings (1974-1975), are consistent with his concepts, e.g. Mathematical Problems (1977) or conceptual events, e.g. White Process (1977). He also reflected on clothing, its function and characteristics. This resulted in designs of basically unwearable clothes, for instance Symbiotic Clothing (first half of the 70s). He came up with the conceptual draft of Clothes Which Are Not Worn (the text was written on the basis of work with clothes between 1962 and 1977). Knížák also investigated the sphere of jewellery and designed several unusual pieces of jewellery, e.g. imaginary jewellery, secret jewellery, invisible jewellery, non-jewellery, etc. Gaseous Jewellery (first half of the 70s) is an example of his method of working in which part of the creative design is a new definition of the problem. He takes the same approach when designing furniture and interiors. Furniture takes on completely unusual forms, e.g. that of a pillar of sound, rooms divided by sound, coloured tapes, gaseous furniture, etc. This conception of furniture and interior decor includes the works Fire Pillar (1974-1975). Knížák also created series of furniture, e.g. Cocub (1971) and Softhard (1974), which reveal his ability to create new perspectives on traditional forms of furniture.

This ability to approach a relatively stabilised sphere in a new way is characteristic of his later works. He creates his fashion, jewellery and furniture designs mainly in the 1980s. He put together many fashion collections, e.g. New Asymmetric (1983), Fur (1983), Softhard (1983), Naked Breast (1970-1986), and a collection of Painted Clothes (1988). He designed collections of jewellery for the face (1970-1985), the nose (1986), the eyebrows (1986), the lap (1973-1986), for the breasts and cheeks (1970-1985), earrings covering the entire ear or changing their form (1985-1986), jewellery for fingers (1989), etc. Many of his works cast a new look on traditional furniture, e.g. Table-Non-table (1983-84), Multifunctional Table (1985), Table for the Big Boss (1986). In the 80s, he designed various sets of tea pots and cups, vases, goblets and glasses, cars, violin heads, altars and monstrances.

A short list of Knížák’s activities giving several examples, and the division of his oeuvre into three periods (which could be characterised as action, conceptual and postmodern) is for methodological purposes above all. Finding certain regularities in his work (conceptual constants, characteristic approaches, etc.) is intended above all to create a kind of basis for realising that these divisions leave out something fundamental from his work. These schematic categories (necessary if we are to get to grips at all with the problem) force a kind of sequence on his activities and the existence of individual, concurrent spheres into which his works can be classified (event, painting, architecture, music, fashion, design, etc.). What is more important, though difficult to describe systematically, is that the work of Milan Knížák can be approached across and through individual spheres and that these spheres are not even spheres from a certain point of view, i.e. they are not specifically fields (i.e. fields in which only certain phenomena belong and no others). Knížák has an aversion to such definitions. Items, phenomena, facts, etc. can be something other than what they are usually regarded as. This apparently trivial fact lends them a certain ambiguity which is finally symptomatic of most of his works and for his oeuvre as a whole. The conceptual playfulness with which Milan Knížák transforms the significance of items and situations and dissolves the original boundary of artistic disciplines while creating other boundaries, makes his work difficult to grasp. It is not just that his activities are difficult to define, but that they force us in many cases to mimic his activities in order that we ourselves initiate a similar process and subject ourselves to a playfulness which is not specified in advance. In addition, the work of Milan Knížák is not concentrated on several artistic problems (themes) but more on an ambiguity which is very difficult to pin down and which, thanks to our actions, the items can keep acquiring anew.

Milan Knížák is an artist whose activities extend into many spheres both inside and outside the art world. His artistic activities include events, fine art, music, architecture, design, fashion, poetry and photography. However, more important than the spheres in which he is active or the media he uses is the fact that he often works in several spheres at once, and that these spheres and media permeate each other and extend across the wide range of his activities.

The diversity and of his activities and the expressive devices he uses are the result of on the one hand his disposition, and on the other his conviction that life and art are deeply linked internally. This means that his art works are also perceived in association with his non-creative social activities. This social dimension is an organic part of his work, since Milan Knížák never wanted simply to create artefacts which would represent him.

Knížák’s creative career began in the 1960s. In his own words, this phase of his work represents an attempt to make of art an ars vivendi (c.f. for example the text of the action lecture Why That Way 1964). He attempts to bring art closer to everyday life and thus provide both art and life another dimension. He created Short Lived Street Exhibitions (1962-64) and various street environments. The emphasis Knížák placed on the totality of life and the connections between all aspects of life led him to look not only for new possibilities of presenting art, but new expressive positions and forms of artistic activity. In his events, art is not restricted only to the professional artist or a circle of experts. It does not only operate within the institutionalised context of a gallery, exhibition or concert hall, and not only for a selected party interested in advance, but enters life as it is lived. The encounter with an artwork is not a secondary, intellectually sensual pleasure, but a challenge to change our lives, i.e. to change our approach to life. (The new expressive forms Knížák uses, i.e. events, manifestations, demonstrations, etc. can also be included under the concept of art and extend the boundaries of what we mean by the word art, though at that time it was not important to Knížák if this was the case, since these new forms for him did not lose their instrumental purpose, i.e. they represented a training in life). This difficult and on a wider scale unrealisable programme, reflecting the overall mood of the 1960s, is the decisive axis of all his artistic and life endeavours. His attempt to incorporate events into the lives of their participants is an endeavour to incorporate art (in a corresponding form) into other life situations. It is the attempt to provoke its recipients to reflect, to discover in themselves the ability to leave behind customary social forms and conceptual stereotypes, and to learn to recognise and appreciate new experiences and to be open to the pleasure to be derived therefrom. Even though in the end the attempt to link art and everyday life cannot be achieved because of their constitutive differences (different methods of perceiving, experiencing and comprehending the contexts in which we find ourselves), the endeavour in itself extends art into other spheres, including multidisciplinary and even media spheres.

Active and conceptual moments alternate and pervade Knížák’s events, people are linked to the game and invited to allow the game to be played out in their own minds. After ambitious events in which several types of activity are linked (A Walk Around the New World 1964, 2nd Manifestation of Actual Art 1965, etc.), Milan Knížák decided to concentrate on a limited number of motifs. From events focussing on social links or a certain routine way of behaving, he began to concentrate on the personal experience of the individual. Events began to appear of a psycho-physical character (Lying Ceremony 1968), or for a restricted number of participants (Difficult Ceremony 1969), in which ritual elements are important (Stone Ceremony 1971). In these events Knížák reached the deeper, more primeval layers of human life and existence. In this respect it is significant that many of his events from the start of the 1970s are entitled ceremonies. In the 70s his events become calmer and their conceptual side deeper. In the latter half of that decade several events are relocated to the space of the mind (the space of the mind is his own term). Events become concepts, though this conceptual aspect is not their only characteristic: many events still relate to human physicality (e.g. Habitation 1979, Human 1979). By virtue of their dematerialisation several events focus on the space of the mind itself (e.g. Spaces 1982). Around this time conceptual mathematically conceived events make an appearance, e.g. Events 1977 or Mathematical Problems 1977. Another difference between his events of the 1960s and 70s is that in the early works it was possible to be drawn violently into events, but as soon as the actions of an event become the inner life, the basic meaning of the event has somehow to be grasped prior to its execution. He creates events focussing on the individual’s perception, e.g. Material Events 1977, Recognition 1977, as well as events such as Friendship with a Tree 1980. This last instance, though it does not exclude a certain community, is intended for participants who are already prepared to understand it. The events were so closely linked with Knížák’s life that this was not only a type of artistic activity, but (especially in the case of his early works) a way of life in itself. This demanding approach to an event is such an important condition for its realisation that it also functions as a natural limit. This was so, for instance, in the case of Event 1984 from 1984, which does not contain any instructions regarding how it is to be executed. It becomes a kind of specific reflection on events as such. Reflection on events comes at a time when the event was waning in Knížák’s work. However, giving up events did not mean simply transferring his activities into other spheres, since the decline of events is at the same time an expression of the concept and expressive significance which they have in the work and life of Milan Knížák. In a series of events entitled Paraphrases from 1989, Knížák returns to certain of his works from the 1960s and 70s. He returns to their subjects as though to topics which can be abstracted therefrom. Events which had been executed in real space with the full involvement of physicality (or were at least so intended), are now transferred in part or completely to the space of the mind. The suspense of the original events created by their incorporation into everyday life is not transposed to the suspense of mental structures. The set of events entitled Paraphrases shows how Milan Knížák deserted what were originally physically and materially executed events, which are no longer repeatable in respect of their physical and material intensity.

Knížák returns to pictures and painting after a relatively long silence in the latter half of the 1980s. More precisely, it was only then that he fully accepted the distinctive character of the image. Pictures from the 1960s, from the earliest phase of his work, which are not simply historical documents but are related to the whole of his output, date back to the cycle Portraits (1964). However, these pictures are so connected with other of Knížák’s activities (Short Lived Street Exhibitions, events) that they cannot be restricted only to the pictorial. Even in the 1970s Knížák used painting more as an instrument (c.f. the cycle Clothes Painted on the Body, or other paintings on textile, etc.), rather than a completely independent expressive means. It was only in the latter half of the 1980s that Knížák discovered painting as such. The result was a number of paintings discovering the medium and reacting to the postmodern paradigm. Sculptural elements appear in some pictures (e.g. Pictures Painted on POP 1989, etc). At the end of the 80s the artist begins painting on objects. It is worth remembering in this respect his early work such as Statue of a Table (1964), Statue of Trousers (1964), etc. The paintings on objects from the end of the 1980s are not conceptual so much as emotional, featuring expressive colour tones.

At the start of the 1990s, Knížák began to concentrate on sculpture. Craftsmanship and formal qualities acquire a predominant role. Previously he had not regarded the craftsmanship of his work as important and had almost wilfully neglected it. Now he emphasised it. However, this was not simply about a purely instrumental method of working. Purity of craftsmanship freed of random movement becomes, along with material perfection, a means of liberating the resulting form from excessive subjectivity and an immediate dependency on the materials. The perfection of the resulting shape, replacing the unrepeatability of the personal processing procedures of industrial production, allows for a greater focus on the artist’s own intention and draws attention indirectly to the more general contents of the work, so that artefacts becomes signs and symbols. The form of processing is now a reminder of Knížák’s conceptual endeavours. It is around this time that the series of works entitled New Paradise is created. This free cycle includes the graphic designs Illustrations to a New Bible 1990, Biblical Landscapes 1991, the installations New Paradise 1990-91, Mutants 1991, 1376-1382 1992, a series of drawings entitled BMC 1992-94, and the installation Barbie 1994-95. A series of masks entitled First Twelve 1991-92 and the installation Creatures and Slightly Gentler Creatures 1993-94 are processed in a similar way.

This overview of the development of Milan Knížák’s work examining individual creative periods and outlining the predominant expressive resources that belong to it, can only offer a partial view of his work. A more important character of Knížák’s creative method, though one which is difficult to put into words, is the interplay of his activities, the breadth of the activities which mutually influence each other, forming a variable and polymorphous background to his individual works.

II.

The next part of this text on Milan Knížák offers examples of his work in the spheres of architecture, music, fashion, jewellery design and production, furniture and interior design. The classification of these spheres of his work corresponds to that given in the first part of this text.

This means that even in this sphere of his oeuvre we can find links with external conditions (materials and social conditions, e.g. the possibility of working in a studio, sales possibilities, various forms of pressure from the authorities, etc.) and internal conditions (his personal development, the immanent development of a certain creative problem, etc.)

Certain accents characteristic of individual periods can be found in Knížák’s work. Certain works from the 1960s, e.g. Fork Building (1963-64), Destroyed Music (1965), Actual, Updated Clothing (1964), Clothes Painted on a Body (1965), Tearing Jewels (1962-70), Jewels for the Entire Body (1963-1964), relate to and supplement in many respects other of the artist’s activities of that time, above all his events. Action, a focus on the public and a certain non-artistry and personal commitment could characterise this early period of Knížák’s output.

At the end of the 1960s and during the 70s it was ceremonies and rituals which resulted from the artist’s demonstrations. In the 1970s, as a consequence of external circumstances, Knížák documented his activities during the 60s and developed and elaborated many themes of his works. The conceptual character of his output intensified. Thinking through certain principles resulted in marginal designs within the framework of the sphere in question. At that time Knížák was thinking about intangible architecture, which led him, for instance, to write the large text entitled An Attempt at a Non-systematic Introduction to the Problem of Intangible Architecture (1970-1985), from which this work includes the excerpt Game of Architecture (1974-1975). At the same time he was creating a comprehensive design for the City in a Desert (1969-72), which represents an architectonic-urban complex accompanied by a vision of a different society. Knížák created musical concepts and was reflecting on the boundaries of music, an activity which resulted, for instance, in Music as Architecture (1968-76). The compositions of this period, e.g. Suspected Imagined Music (1978) or Simple Buildings (1974-1975), are consistent with his concepts, e.g. Mathematical Problems (1977) or conceptual events, e.g. White Process (1977). He also reflected on clothing, its function and characteristics. This resulted in designs of basically unwearable clothes, for instance Symbiotic Clothing (first half of the 70s). He came up with the conceptual draft of Clothes Which Are Not Worn (the text was written on the basis of work with clothes between 1962 and 1977). Knížák also investigated the sphere of jewellery and designed several unusual pieces of jewellery, e.g. imaginary jewellery, secret jewellery, invisible jewellery, non-jewellery, etc. Gaseous Jewellery (first half of the 70s) is an example of his method of working in which part of the creative design is a new definition of the problem. He takes the same approach when designing furniture and interiors. Furniture takes on completely unusual forms, e.g. that of a pillar of sound, rooms divided by sound, coloured tapes, gaseous furniture, etc. This conception of furniture and interior decor includes the works Fire Pillar (1974-1975). Knížák also created series of furniture, e.g. Cocub (1971) and Softhard (1974), which reveal his ability to create new perspectives on traditional forms of furniture.

This ability to approach a relatively stabilised sphere in a new way is characteristic of his later works. He creates his fashion, jewellery and furniture designs mainly in the 1980s. He put together many fashion collections, e.g. New Asymmetric (1983), Fur (1983), Softhard (1983), Naked Breast (1970-1986), and a collection of Painted Clothes (1988). He designed collections of jewellery for the face (1970-1985), the nose (1986), the eyebrows (1986), the lap (1973-1986), for the breasts and cheeks (1970-1985), earrings covering the entire ear or changing their form (1985-1986), jewellery for fingers (1989), etc. Many of his works cast a new look on traditional furniture, e.g. Table-Non-table (1983-84), Multifunctional Table (1985), Table for the Big Boss (1986). In the 80s, he designed various sets of tea pots and cups, vases, goblets and glasses, cars, violin heads, altars and monstrances.

A short list of Knížák’s activities giving several examples, and the division of his oeuvre into three periods (which could be characterised as action, conceptual and postmodern) is for methodological purposes above all. Finding certain regularities in his work (conceptual constants, characteristic approaches, etc.) is intended above all to create a kind of basis for realising that these divisions leave out something fundamental from his work. These schematic categories (necessary if we are to get to grips at all with the problem) force a kind of sequence on his activities and the existence of individual, concurrent spheres into which his works can be classified (event, painting, architecture, music, fashion, design, etc.). What is more important, though difficult to describe systematically, is that the work of Milan Knížák can be approached across and through individual spheres and that these spheres are not even spheres from a certain point of view, i.e. they are not specifically fields (i.e. fields in which only certain phenomena belong and no others). Knížák has an aversion to such definitions. Items, phenomena, facts, etc. can be something other than what they are usually regarded as. This apparently trivial fact lends them a certain ambiguity which is finally symptomatic of most of his works and for his oeuvre as a whole. The conceptual playfulness with which Milan Knížák transforms the significance of items and situations and dissolves the original boundary of artistic disciplines while creating other boundaries, makes his work difficult to grasp. It is not just that his activities are difficult to define, but that they force us in many cases to mimic his activities in order that we ourselves initiate a similar process and subject ourselves to a playfulness which is not specified in advance. In addition, the work of Milan Knížák is not concentrated on several artistic problems (themes) but more on an ambiguity which is very difficult to pin down and which, thanks to our actions, the items can keep acquiring anew.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar