Klasika performansa i vulvo-mesnog materijalizma.

Ritualna odbojno-komično-senzualna divlja ekstaza bijesnog i radosnog tijela.

Danas to izgleda poput neke srednjovjekovne distorzije.

www.caroleeschneemann.com/

eai.org/artistTitles.htm?id=6735

The singular American artist Carolee Schneemann is perhaps best known for her expressive paintings, installations, films, and videos from the past five decades and their unwavering focus on identity, subjectivity, and sexuality. Born in 1939 in Fox Chase, Pennsylvania, she received her B.A. from Bard College and an M.F.A. from the University of Illinois. After moving to New York in 1961 with James Tenney, who was then a composer-in-residence at Bell Telephone Labs in New Jersey, Schneemann was introduced (via composers Philip Corner and Malcolm Goldstein) to the cofounders of the Judson Dance Theater. In the mid-1960s she produced some of her earliest performances with the group at Judson Church, including Newspaper Event, 1962; Lateral Splay, 1963; Chromelodeon, 1963; and Meat Joy, 1964, and played as Manet’s Olympia in Robert Morris’s Site, 1964. - artforum.com/

1964-66, 29:51 min, color, silent, 16 mm film on video

Schneemann's self-shot erotic film remains a controversial classic. "The notorious masterpiece... a silent celebration in colour of heterosexual love making. The film unifies erotic energies within a domestic environment through cutting, superimposition and layering of abstract impressions scratched into the celluloid itself... Fuses succeeds perhaps more than any other film in objectifying the sexual streamings of the body's mind" Ñ The Guardian, London -- EAI

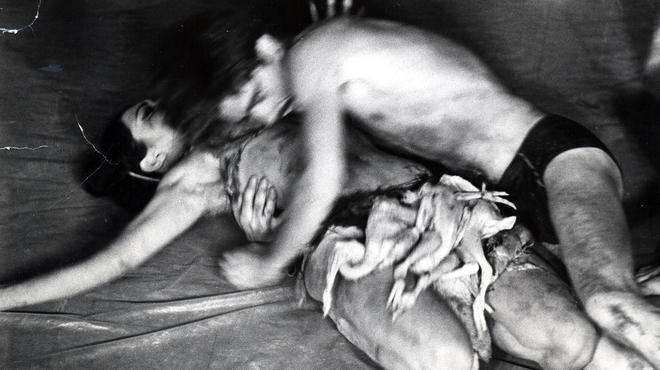

Meat Joy is an erotic rite -- excessive, indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chicken, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, ropes, brushes, paper scrap. Its propulsion is towards the ecstatic -- shifting and turning among tenderness, wildness, precision, abandon; qualities that could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent. Physical equivalences are enacted as a psychic imagistic stream, in which the layered elements mesh and gain intensity by the energy complement of the audience. The original performances became notorious and introduced a vision of the "sacred erotic." This video was converted from original film footage of three 1964 performances of Meat Joy at its first staged performance at the Festival de la Libre Expression, Paris, Dennison Hall, London, and Judson Church, New York City. -- EAI

Meat Joy: First performed May 29, 1964, Festival de la Libre Expression, Paris.

Filmed by Pierre Dominik Gaisseau. Editor: Bob Giorgio.

Viet Flakes (1965)

1965, 7 min, toned b&w, 16 mm film on video

Viet Flakes was composed from an obsessive collection of Vietnam atrocity images, compiled over five years, from foreign magazines and newspapers. Schneemann uses the 8mm camera to "travel" within the photographs, producing a volatile animation. Broken rhythms and visual fractures are heightened by a sound collage by James Tenney, which features Vietnamese religious chants and secular songs, fragments of Bach, and '60s pop hits. "One of the most effective indictments of the Vietnam War ever made". — Robert Enright, Border Crossings. -- EAI

Sound Collage: James Tenney.

Carolee Schneemann (b. 1939) UbuWeb

Meat Joy (1964)

Meat Joy (1964)  Viet Flakes (1965)

Viet Flakes (1965)  Fuses (1965)

Fuses (1965)  Snows (1967)

Snows (1967)  Plumb Line (1968-71)

Plumb Line (1968-71) Carolee Schneemann's pioneering work ranges across disciplines, encompassing painting, performance, film and video. Her early and prescient investigations into themes of gender and sexuality, identity and subjectivity, as well as the cultural biases of art history, laid the groundwork for much work of the 1980s and '90s. Her bold challenges to taboo and tradition can be seen as inspiring and influencing artists as varied as Paul McCarthy, Valie Export, the Guerrilla Girls, Tracy Emin and Karen Finley.

While she is often described as a performance artist, Schneemann first studied painting, and that training informed the course of all her subsequent work. It can be seen in her continuing identification as a painter and a formalist, in her attention to art-historical figures such as CŽzanne, and in the hand-coloring and mark-making to which she subjected the surface of some of her films. However, the effect of her early experience with painting was also reactive and negative; she recognized, as a woman in the early 1960s working in a male-dominated medium, that "the brush belonged to abstract expressionist male endeavor. The brush was phallic." This realization coincided with an explosion of new artistic forms, and while Schneemann would never give up painting, she turned her attention to the downtown New York avant-garde's locus of film, dance, theater, and performance.

Her involvement with this scene, including work with the Judson Dance Theater and time spent at Warhol's Factory, as well as participation in events such as Robert Morris's Site (1964), in which she appeared onstage as Manet's Olympia, proved crucial to her own concept of what she would call "kinetic theater." Although she had experimented with performance as early as 1960, her work in this vein went public with the notorious 1964 action and film Meat Joy. This "celebration of flesh as material," replete with naked bodies, raw fish, chickens, and sausages, was contemporaneous with the sensationalist Viennese Aktionist group, and, at least superficially, shared some of the concerns of those artists, who referred to her as their "crazy sister." However, rather than pursuing their interests in the scatological and the morbid, Schneemann presented Meat Joy as an "erotic rite," foregrounding human sexuality and Dionysian ecstasy with a powerful and subversively affirmative spirit. This spirit asserted itself even more explicitly a year later, in her "anti-porn," collage-film Fuses, conceived of as a response to work by her friend, the experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage. The film challenged dominant modes of interpretation, and was also a provocation to both the avant-garde film establishment and the feminist movement.

This go-it-alone criticality is one of the major strands of Schneemann's work. When critiqued for her interest in sexuality and use of her body as medium, she has always offered an unapologetic defense, pointing out, for example, "If I am a token, I'll be a token to be reckoned with." Her insistence on integrating the form and content of her art can be seen as quite radical, in that it collapses work and life, thought and flesh, nature and culture Ñ forms charged by repression and the strategic deployment of those forms. For Schneemann, the focus on the "experiential erotic body" is a method of empowerment, and an antidote to what she sees as a tendency of feminist art historians to discuss female sexuality exclusively as a male construction. Schneeman's project, then, is in some ways concerned with reclaiming those signifiers, actions, and ideas that have historically been denied women, and, to a lesser degree, artists in general. Her work should not solely be viewed as feminist, although she is certainly a pioneer in that area. Rather, her focus has also been on countering traditional art historical accounts, and in mapping what she calls "Istory," in an attempt to see "where the taboos and censorious conventions are embedded aesthetically." This tendency to identify what has been deemed sacred and what has been declared obscene can be seen in works like Art is Reactionary (1987), and in her research into historic artifacts as far-flung as Victorian art-books and Neolithic cave drawings.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, and up to the present, Schneemann has continued making work in diverse media, including writings and installations. Looking back on her groundbreaking work of the 1960s and '70s, it is important to recognize that, to a certain degree, she was inventing modes of resistance as she went along. Whether it was the notion of what feminism looked like and how it picked its battles, or the notion that art history was clearly written from a position of power, her work has always employed a criticality that was ahead of its time.

Born in 1939 in Fox Chase, Pennsylvania, Schneemann received a B.A. from Bard College and an M.F.A. from the University of Illinois, and holds Honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from the California Institute of the Arts and the Maine College of Art. Her work has been exhibited throughout the world, at institutions including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Centro de Arte Reina Sof’a, Madrid; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Film Theatre, London; Tate Liverpool, UK, and PPOW Gallery, New York. In 1997, a retrospective of Schneemann's work entitled Carolee Schneemann - Up To And Including Her Limits was held at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. A later retrospective of over forty works was exhibited in 2010 at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, State University of New York at New Paltz.

Schneemann has received an Art Pace International Artist Residency, two Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grants, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Gottlieb Foundation Grant, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the College Art Association, and an Anonymous Was A Woman award. Her published books include Cezanne, She Was A Great Painter (1976); Early and Recent Work (1983); More Than Meat Joy: Complete Performance Works and Selected Writings (1979), and Imaging Her Erotics - Essays, Interviews, Projects (2002). She has taught at many institutions, including New York University, California Institute of the Arts, Bard College, and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Carolee Schneemann lives in New Paltz, New York. -- EAI

RELATED RESOURCES:

Carolee Schneemann in UbuWeb Sound

Carolee Schneemann in UbuWeb Sound  Carolee Schneemann in UbuWeb Historical

Carolee Schneemann in UbuWeb Historical| Ask the Goddess Performance 1993-97. The Vulva speaks: "If the traditions of patriarchy split the feminine into debased/glamorized, sanitized/ bloody, madonna/whore... fractured body, how could Vulva enter the male realm except as "neutered" or neutral... "castrated"? In this 1991 performance, Schneemann personifies the vulvic realm in an exploration/ examination of the cultural taboos and secret histories of the vulva. Vulva's direct interaction with the viewer creates a visual, verbal and experiential dialogue with the audience. |  | |

Schneemann, regarded as one of the few who consistently creates a heterosexual eroticism truly based in the feminine, unveils her latest studies, inviting the audience into this co-generative piece.

| ||

| Cycladic Imprints 1991-93 Multimedia installation: 17 motorized violins, 360 slides, 2 dissolve units, 4 synchronized projectors project continuous images of Cycladic sculptures, stringed instruments and human torsos over the painted wall. 20 x 36". sound: loop duration approx. 15 minutes. Quadraphonic sound collage by Malcolm Goldstein. | |

| "This multi-image slide projections dissolve in relays of art historical representations of the female body from painting, sculpture, and photography onto a wall of assemblage of mechanized violins and painted hourglass-shaped silhouettes. Schneemann creates an enveloping space in which she challenges the master narrative of the female nude as muse. The amalgam of body, instruments, and machine defines the gallery as an arena of shared consciousness in the tradition of Schneemann's "kinetic theatre". She triumphs in her mission to create an erotic morphology. (Robert Riley, San Francisco Museum of Contemporary Art) Installed at the Randolph Stree Gallery, Chicago (1992), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1991), Emily Harvey Gallery (1990), The Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati. | ||

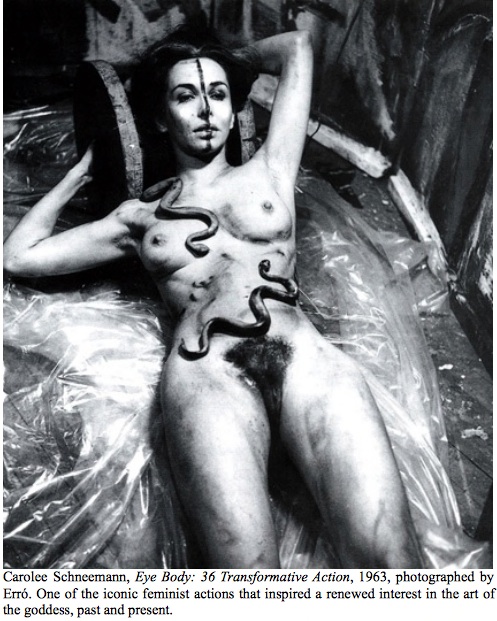

| Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions 1963

Paint, glue, fur, feathers, garden snakes, glass, plastic with the studio installation "Big Boards". Photographs by Icelandic artist Erró, on 35 mm black and white film.

| ||

| ||

| Schneemann's "Action for Camera" in which she merged her own body with the environment of her painting/constructions... "I wanted my actual body to be combined with the work as an integral material-- a further dimension of the construction... I am both image maker and image. The body may remain erotic, sexual, desired, desiring, but it is as well votive: marked, written over in a text of stroke and gesture discovered by my creative female will." - CS |

Four Fur Cutting Boards

| Fresh Blood: A Dream Morphology Dual slide projection system with dissolve unit, pre-recorded and spoken text. Sound collage. Live relay video feeds into four monitors. Red umbrella, red pajamas, watering can, door, raised table, etc. 1981-87. Based on a menstrual dream which asks the question "what do a red umbrella and a bouquet of dried flowers stuffed with little dolls have in common?" The resulting iconography of related images combine "V" symbols from the human body, other organic forms, sacred artifacts, common objects to form the projection sequence. | ||

| CS is joined by her double-- a black woman as nurse, judge, western union-- they present unconscious and active links in a shared history which is personal, racial, political and sexual. | |||

| "Fresh Blood- A Dream Morphology" posited female physical exposeure the feminine as normative. In examining our most taboo viscerality I was built an ethos in which male phobias were eliding. I would invert the projects of the unsanitary leakage, abject, I could posit all the wet bloody cyclic not only in it's physicality, but in a conceptual frame of positive range so that the phobic masuline would have to shrivel and cower... the functions of my body would not be symptomatic or all that is not male." | |||

|  | |||

| "...I wanted to see if the experience of what I saw would have any correspondence to what I felt-- the intimacy of the lovemaking... And I wanted to put into that materiality of film the energies of the body, so that the film itself dissolves and recombines and is transparent and dense-- as one feels during lovemaking... It is different from any pornographic work that you've ever seen-- that's why people are still looking at it! And there's no objectification or fetishization of the woman." –Carolee Schneemann | ||||

| Gift Science Construction in wooden box: slides, mirrors, moving lights, paint, bird. 41.25" x 15/5" x 5". 1964. Gift Science is an assemblage incorporating simple gifts within an abandoned window box. Daniel Spoerri on his visit to NYC in 1964 brought the heat sensitive glass radiometer. My companion James Tenney, offered the large glass slides of computations and prints of an Edgar Varese score. Erro gave the gift of a small stuffed bird; from Arman– a science toy of curved blades turning when heated by a light. Gift Science continued my use of motors and kinetic elements (begun in 1963 with Four Fur Cutting Boards), composing fragile moving elements and small lights within the fractured mirror glass. These mirrors were angled to capture the viewer's own presence, and to reflect continuously changing refractions which illuminate the glass interiors. | |

| The gifts were indicative of a comradely respect which was unusal for a young woman artist to experience in those years. The gifts indicate the richness of exchange between artists of Paris and New York at that time. - Carolee Schneemann, 1996 | ||

|  | |

| Hand/ Heart for Ana Mendieta 1986 Center Panels: Chromaprints of 1986 physical actions- paint with blood, ashes, syrup in snow with hand tracing. Side panels with: acrylic paint, chalk, ashes on paper. Total size: 154" x 57" composed of 12 triptychs each 12" x 57". An homage created for the artist Ana Mendieta, at the time of her death. | ||

Illinois Central: Kinetic Theater

| Infinity Kisses 1981-88

Wall Installation, Self-shot 35mm photographs; Xerachrome on linen containing 140 images: 7' x 6'.

Collection: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.  | ||

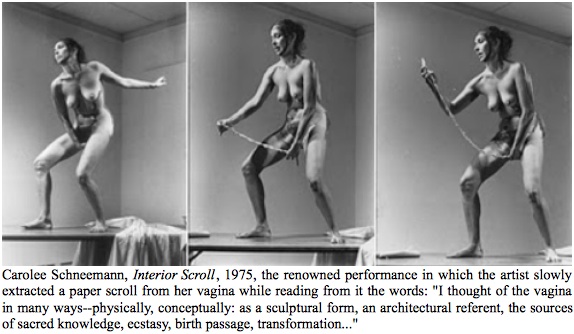

Interior Scroll

| Interior Scroll 1975 Performance. Performed in East Hampton,NY and at the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado. Schneemann ritualistically stood naked on a table, painted her body with mud until she slowly exracted a paper scroll from her vagina while reading from it. |  | |

| "I thought of the vagina in many ways-- physically, conceptually: as a sculptural form, an architectural referent, the sources of sacred knowledge, ecstasy, birth passage, transformation. I saw the vagina as a translucent chamber of which the serpent was an outward model: enlivened by it's passage from the visible to the invisible, a spiraled coil ringed with the shape of desire and generative mysteries, attributes of both female and male sexual power. This source of interior knowledge would be symbolized as the primary index unifying spirit and flesh in Goddess worship." -CS | ||

|  |

| Known/Unknown- Plague Column 1996 Multimedia Installation. 4 video monitors (continuous play with sound) "branches", "breasts", lighting components, wall panel. | |

| Known/Unknown combines photographic, video and sculptural elements in an installation that continues Schneemann's investigation into transgressive and denied aspects of the unconscious, nature, gender and the body. The installation examines relationships between health and illness, between cellular and microscopic representations of visual information where different instruments present biological data in relation to clinical medicine; the guise of objectivity colludes with personal experience. Scheemann repositions the images' visual intimacy, enabling us to invade aspects of the body which are cellular, erotic and clinical. (The term "plague column" derives from a discovery made during a trip to Australia, where Schneemann was drawn to photograph a sculpture, later identified as a "plague column" (1750), built by monks as cult objects to protect their villages against bubonic plague.) | ||

Letter to Lou Andreas Salome

| Meat Joy 1964 . | Judson Church, NYC. Group performance: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, plastic, rope, shredded scrap paper | |

| ||

| First performed as part of the First Festival of Free Expression at the American Center in Paris, and later at Judson Memorial Church in NYC. "Meat Joy has the character of an erotic rite: excessive, indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, rope brushes, paper scrap. It's propulsion is toward the ecstatic-- shifting and turning between tenderness, wilderness, precision, abandon: qualities which could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent." | ||

| More Wrong Things 2001 Fourteen video monitors suspended from the ceiling within an extended tangle of wires, cables and cords. Video loops seen on the monitors present a compendium of "Wrong Things"; juxtaposing Schneemann's visual archives of personal and public disasters. These elements are composed in relation to the beams, conduits and pipes which define the distinctive architectural aspects of WHITE BOX gallery space. This work also responds to current trends of costly fabrication and refined presentation. A wall of recent Iris prints further integrates sources of more wrong things. |  | |

| Review of More Wrong Things from Tema Celeste magazine... Review of More Wrong Things by Barbara Leon... | ||

Mortal Coils

Portrait Partials

Snows

| Unexpectedly Research 1962-92

Images made and performed 1962-82. Laser prints on board with text. 4 panels: 32" x 40" each.

Unexpectedly Research clarifies the influence of non-western and Indo-European artifacts on my work. The shameless erotic power and self-display of a New Guinea owl goddess offers a parallel to my actions in Body Collage (1968). The juxtaposition of two lions mating with the self-shot orgasmic heads from my film Fuses (1965) demonstrates a relation to animal sexuality. The Minoan priestess holding serpents in her hand, a sculpture from 2,000 B.C., offers a precedent to my unconscious placement of garden snakes on my body as a part of the "36 Transformative Actions" of Eye Body (1963). In each instance, the affinity image was discovered many years after my actual enacted image. This recombine of image sources in Unexpectedly Research brings forward psychic aspects of personal exploration of art history. | ||

| Up to and Including Her Limits 1973-76 . | Performance. live video relay. Crayon on paper, rope and harness suspended from ceiling. The Kitchen. NYC. | |

| ||

| Up To And Including Her Limits was the direct result of Pollock's physicalized painting process.... I am suspended in a tree surgeon's harness on a three-quarter-inch manila rope, a rope which I can raise or lower manually to sustain an entranced period of drawing– my extended arm holds crayons which stroke the surrounding walls, accumulating a web of colored marks. My entire body becomes the agency of visual traces, vestige of the body's energy in motion." | ||

Venus Vectors

Vesper's Pool

| Video Rocks

Multimedia installation: 200 hand cast rocks (cement, glass, ashes, wood), 5 video monitors, 10 plexiglass rods with 10 halogen lights, 2 channel video, feet walking on rocks; painting: acrylic on paperpainting: 9' x 6'.

Installation area: 30' x 16'. 1987-88. The disparate materials which compose Video Rocks first appeared in a dream concerning diminishing perspective. I was unsure whether the dream was a unique instruction to concretize the image dimensionally or whether I was dreaming a version of another artist's work. Several weeks of research were required before I felt reassured that the drawings I had begun from the dream did not already exist. Grief and personal loss also became motives. I made a commitment to hand-cast 4 or 5 "rocks" a day. Pouring, stirring, shaping became a ritual concentration. | ||

| The conceptual question proposed by the dream concerned tactility and virtuality. A flow of "rocks" resembling Monet's Water Lilies, cow manure or huge cookies led the eye into a row of video monitors on which sequences of various feet were seen rhythmically crossing the virtual rocks placed in a landscape. While the monitors displayed a physical action made virtual as video, walking on the actual rocks is forbidden due to their evident fragility and arrangement as a sculptural accumulation. By repeatedly pressing my feet and my body into the rock mixture, a canvas wall was composed of the same gritty materials as the rocks. The luminous light rods are a translation of narrow beams of yellow spotlights randomly marking the rocks in the dream. | |||

| Vulva's Morphia 1995

Total Wall Installation: 5 x 8 feet. Each panel 8.5' x 11". text 58" x 2".

A visceral sequence of photographs and text in which a Vulvic personification presents an ironic analysis juxtaposing slides and text to undermine Lacanian semiotics, gender issues, Marxism, the male art establishment, religious and cultural taboos. | |

|  |

|  With eight performers climbing on suspended ropes, it was "conceived as an aerial work for ropes rigged across the canal at San Marco... finally realized at Saint Mark's Church in the Bowery (Venetian name sake), then later rigged in a grove of trees to be filmed. The transparencies of Venice still motivated the actual aerial arrangement of ropes which enclosed or surrounded the audience seated below." With eight performers climbing on suspended ropes, it was "conceived as an aerial work for ropes rigged across the canal at San Marco... finally realized at Saint Mark's Church in the Bowery (Venetian name sake), then later rigged in a grove of trees to be filmed. The transparencies of Venice still motivated the actual aerial arrangement of ropes which enclosed or surrounded the audience seated below." | |

Water Light/ Water Needle 1966

Performance, St. Mark's Church, NY and The Havemeyer, Estate, Mawah, NJ.

| ||

Breaking the Frame: A Cinematic Immersion Into The Art and Life of Carolee Schneemann at the 51st New York Film Festival

G. Roger Denson

It is questionable whether even Sigmund Freud has received a cinematic treatment as evocative of his impact on the culture around him as Carolee Schneemann has received from Marielle Nitoslawska's film, Breaking the Frame. But then Freud and most other biographical subjects haven't had the good fortune of having their every waking step imprinted as persistently--and as presciently--as Nitoslawska recorded Schneemann for what came to accumulate lovingly into several years. The reward has been more than gratifying for both filmmaker and subject, reaching as it does as deeply into Nitoslawska 's own creative reserve to mirror her impressions of a woman who came as close as any artist in America to being a sibyl-like seer of aesthetic and political possibilities for the last decades of the great modern century.

Whether we credit Nitoslawska's indefatigable burrowing through five decades of Schnemann's personal archives, or her reading of the psyche of a woman who has lived to see herself become an American Treasure, Nitoslawska, a graduate of the Polish National Film School in Lodz, composed a consummate fusion of music, imagery, narrative and time that goes beyond the ordinary crafting of a biographical profile. Imposing cinematic rhythms and restraints that make Schneemann seem at times a mythopoetic cypher--an icon we value as much for her reflections on Nature as for her calling out of the power-intoxicated anthropomorphisms that indict the human steerage of Nature into misogynistic and erotophobic dead ends.

The film also owes considerably to film editor Monique Dartonne (also known for her work on the film Incindies) and sound editors Catherine Van Der Donckt and Benoit Dame, who together with Nitoslawska craft a total artwork evoking an epochal tonality that we immediately associate with the bohemian enclaves of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, if not beyond. Those viewers wanting a linear and hard-focused factuality may be put off by the attention to cinematic mannerisms that function as visual corollaries to the cadences of lyric poems or the notation of songs. But even the most stoic audiences should be impressed by the kaleidoscopic phasing of a life that came to embody, if not reconcile, a number of otherwise conflicting artistic and intellectual movements of her day.

While the filmmakers' lenses and microphones make themselves generously evident, this is entirely in accord with the way that Schneemann herself made film and performance art in her early years--with the artist's own voice generously heard. Following Schneemann's lead, Nitoslawska supplies her own stream of voiceover to Breaking the Frame, a convention that here doubles as her framing of scenes and her appraisal of Schneemann as an artist.

"Your flamboyant acts of transgression. Physical and metaphysical connotations. Orifices of erotic sensate bodies, tunnels linking inside to outside. PORTRAIT PARTIALS. Sacred vitality--invoking, conjuring, living."

Such voiceovers throughout the film ensure that we never steer our attention adrift from the woman and artist. Rather our continual consciousness of the filmic process, in remaining true to the structural dictates of avant-garde filmmakers of the time being recalled, makes us aware of the protean evolution that Schneemann was experiencing as she willed herself to become a medium that is every bit as materially expressive as any painting, video or film. Through Schneemann's body, painting was made performance even as performance became painting. The same interchange can be said to have melded Schneemann's sculptures to her ideas, her feminism to her eroticism, her appreciation of history to the modernity that defined her ideological outlook, her biology to the symbology of her culture. Schneemann was nothing if not consummately aware of the potentiality of things becoming interchangeable, one of the traits that she impressed on the artists around her as well as on every generation that came after her to mediate between the materiality and the ideality of the world.

With artists today clamoring to remake and redefine the frame of a picture with virtual theory and technology, we may have to remind ourselves that the film's title, Breaking the Frame, references the state of the international art movements, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, by which artists were striving to break free of the frame and the format of pictures that dominated the reception and the perception of art. Of course, Schneemann ranked among those who advanced such concerns to the point that making a picture became more strategically self-conscious to the artists of the 1960s than the picture itself. And from there she pushed the process of "making" art to the point where that making becomes reconceptualized as performance in a theatrical sense.

But Nitoslawska prefers not to dwell on histories. "I structured the film thematically," she informed me, "rather than by historical periods as in art history, which would be linear, predictive, and utterly unsuitable for a subject like Schneemann. Each sequence conceptually relates to various dimensions of the body (the body being essential in Schneemann's oeuvre). So we have the historical body that questions how art histories are written; the sexual/gendered body as the source of vital energies; the political body, actively engaged in the zeitgeist; the mothering/mortal body, where life is given and taken; the relational body, that unpacks love, violence, social correlations... And so on. Each section has a concentric form, like a Russian nestled doll. At its heart, it is always collaged with other elements, as with the idea of dislocating time and space, of dodging the concreteness of documentary, of enlarging and embodying the art-life nexus of the film."

In making the film itself a virtual consciousness, Nitoslawska and her team help us experience Schneemann's profound difference as both an artist and a woman of her generation. Whereas many other groundbreaking artists around her looked to experimentation and theory as discrete elements and processes in the formation of their ideas and art, Schneemann seems to merge with phenomena and mind as organic wholes not to be broken down, but rather to be refashioned into new intertwining ways of experiencing them. Whereas Fluxus Art, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art, crystalized into movements inhabited by many artists, Schneemann seemed always to have been a singular movement unto herself, an entity who lived art in a way that Duchamp lived art. In this respect, Nitoslawska's finest accomplishment has been to depict Schneemann's unity with Nature and Humanity as the center from which her art and thought organically grew. And as such we come to appreciate the restraint with which Schneemann keeps her art from becoming systematic or formulaic in the fashion of the Fluxus, Conceptual and Performance Artists with whom she is often historically referenced.

But Breaking the Frame never dwells long on either cultural or media issues. Its meandering, often dreamlike, unwinding impresses a range of conversations with the artist conducted on various planes of perception and cognition at once. We are fortunate that Nitoslawska never makes any one of these conversations seem instructional. We receive them as if we are roaming through Schneemann's large rural house, where each room has its own psychic television tuned to a different station of the universe, however much the "programming" refers back to some aspect of the artist's life as a vessel of the great Continuum. Nitoslawska in fact considers Carolee's house "to play an important 'supporting role' in her meditation on space--a physical, domestic, corporeal, and conceptual evocation of the edges and fractures where art is generated." The formal properties of the film mimic the rooms of Schneemann's house, to take on character traits of space. The dark rooms recall memories hard to extract from unconsciousness.

The evocations of the landscape around Schneeman's house are equally affecting. The pools of water and rain psychologically cleanse us of any remorse that comes with reminders of the passage of time. Verdant landscapes seem to justify urges and spontaneity. Not that Nitoslawska burdens her film with gratuitous metaphors. Every choice is conducive to conveying meaning about the moment's environment that Schneemann communes with to the point of merging with Nature as discreetly as a chameleon acclimates to its surrounding. (I here recall the writings of the Surrealist anthropologist, Roger Callois.) If Schneemann came to be associated with the goddess by second-wave feminists, it has less to do with her early embrace of neolithic, bronze- and iron-age iconographies and embodiments of the goddess--of which she was among the first modernists to point to (and would later pave the way for the mythopoetics of such artists as Matthew Barney and Mariko Mori). On the contrary. Nitoslawska helps us to understand that Schneemann assumes not the exalted stature of the goddess, but rather models the process by which living things epitomize processes of nature that in totality dwarf the human condition. The gods, after all, were nothing more than anthropomorphized nature, a process that Schneemann in Breaking the Frame is portrayed reverting to when blurring the animate and inanimate features of the world in her art and thereby subsuming all cultural values in that art's psychological deliquescence.

It helps that much of the film takes on the warm glow of the archival footage that is surviving the now-passing first television generation. The effect of our virtual stay in Schneemann's house is to walk away retaining the living evidence that the artistic avant-garde of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s had more than mere aesthetic and theoretical presence. They were an activist force against governmental and ideological intrusions upon individual liberties however discreetly their forms and processes subverted conventionality. It is the more discreet workings of this generation that compels Breaking the Frame to function as some amalgamation of poem, dream journal, photo album, laboratory log, cultural memento, archeological dig, and liberation manual for an era of artistic experimentation and confrontation. In short, Breaking the Frame is as much a cultural time capsule as a biographical testament.

Nitoslawska makes it evident that our fortune in having Carolee Schneemann with us today has a good deal to do with her being among our last living participants in the strategic break down of taboos that society leveled against the body and its natural functions as late as the 1960s to 1980s. In this respect, Schneemann is much more than one of the significant innovators to have evolved the Pollock and Kline-like actions of modernist action painting into an art of performance that replaces the brush with the body of the artist, while making the artists as much the art as the object and processes they make. The many visual and performance artists in the West who came after Schneemann with their focus and exposure of the body, its functions and products in art, found a more open cultural atmosphere in large part because Schneemann and others of her generation (Kenneth Anger, the Vienna Actionists, Yoko Ono, Yayoi Kusama, Charlotte Moorman, Jack Smith) challenged the remnant superstitions and state ordinances--what amounted to a staggering range of religious, scientific, philosophical, and legislative closures that most of us only read about today. It's hard for us to imagine in our 21st-century, erotically-charged media stream, how the outlawing of public displays of nudity and their referents as pornography legislated an enforcement of moral codes that landed confrontational artists of Europe and North America in jails. At the same time, the challenge Schneemann took on was to impress a newly iconic mediation of art as vehicle for social codes while taking on the political responsibility of remaking those codes and the cultures they build.

If Schneemann's contribution to art history proves more substantial than the performance art of her male contemporaries of the 1950s and 1960s, it is because as one of the earliest exponents of overt feminist dissent in art, she not only famously displaced the millennia-old objectifcation of the female body by male artists with the literal subjectification of her own body as the simultaneously animate mind, instrument, and medium. Add to this her role in tandem with the feminists of her generation and her art is seen as recontextualizing such historic women artists as Artemesia Gentislechi, Hannah Höch, Frida Kahlo, Maya Deren, Lee Miller and Merit Oppenheim, as proto-feminist activists who made the female body (as distinct from the female depiction) a politicized, even polarizing, declaration of independence and autonomy. For good or for bad, the price Schneemann paid for making both art and political history is to have her less activist art, particularly her abstract painting and sculpture, reduced to categorization as remnants or accessories of her performance and body art, rather than as significant art of its own merit.

Breaking the Frame doesn't make art historical pronouncements. It's too lyrical and narrational to be so programmatic. But we are given ample glimpses of Schneemann's movement through art history in the context of the art enclaves that are iconic to this day. Clips from archives are largely circumspect, keeping with Nitoslawska's unifying modus operandi of integrating them into a stream of consciousness, more a seamless fabric than a patchwork composition. In such a stream, glimpses of Schneeman's and other artists' art come into and out of view. One such work is filmmaker Stan Brakhage's film Cat's Cradle (1959), where Carolee is seen chopping onions, "much to her dismay". About this scene, Nitoslawska informed me, "Carolee wished to be portrayed as a painter. She was painting a portrait of Jane Brakhage at the time, and I couldn't believe it when we found five frames of Carolee doing just that, hidden in the Brakhage film. They were there but couldn't be perceived, since five frames is a fifth of a second in projection. So we multiplied the five frames, slowed them right down, and Carolee finally got her due [via Brakhage] fifty years later. (I love the way history is written and rewritten!)"

Nitoslawska clearly relishes the onscreen scenes of Schneemann's eariest performances, such as the iconic Meat Joy, first performed as part of the First Festival of Free Expression at the American Center in Paris, and later at Judson Memorial Church in NYC. "Meat Joy has the character of an erotic rite", Nitoslawska effused about the work's Dionysian lineage. Schneemann's own description of Meat Joy is more grounded in the art media concerns of the period conjoined, in Pop Art fashion, to a virtual shopping list of consumer items and food stuffs that she helped to legitimize as components of art and performance in the early 1960s. "Excessive, indulgent, a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, rope brushes, paper scrap..." But Schneemann departs from and extends the Pop fetish into an intoned litany of human affects that convey Meat Joy to be at its source reverent of Nature: "It's propulsion is toward the ecstatic--shifting and turning between tenderness, wilderness, precision, abandon: qualities which could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent."

The influences of artists on Schneemann--and the influence she in turn had on them--are only fleetingly alluded to, but no less saliently. "From the 1950s & 1960s, I mostly focus on James Tenney and Brakhage, as they were the most important in Carolee's formative years. But there are several other references. We see an excerpt of Anthropométrie de l'Époque bleue by Yves Klein (1960) edited in startling contrast with Meat Joy, to show just how radical it was. Carolee was staying with Klein's wife while performing Meat Joy in Paris in 1964, but Yves Klein had already passed away."

From the 1970s we see excerpts from Schneeman's film, Kitch's Last Meal (1973-76). Nitoslawska also includes a long scene with Schneemann and Anthony McCall, with voiceover explaining that the "A" in Schneeman's ABC-We Print Anything-In the Cards (1976) stands for Anthony. "There's also a gorgeous sequence of Carolee spinning in a huge parachute dress that covers and uncovers her naked body", Nitoslawska points out with glee. "This is from Claes Oldenburg's Waves and Washes (1966), filmed by Stan Van Der Beek. Carolee had performed in several of Oldenburg's happenings during his Storefront days. We also see Carolee in an Al Hansen happening from 1965, with several Fluxus friends in the entourage."

The film has also been bequeathed further authenticity of its era by a range of artists who were important to both Schneemann and to the avant-gardes of music, film, video, visual art, theater, dance, and performance art. A good deal of the music saturating several of the film's scenes, and which take on their own biographical association with Schneemann, is composed by her former companion and collaborator, James Tenny--whose handsome young, then middle-aged, countenance animates every cut it inhabits. "Tenney's twenty compositions (spanning five decades) constitute the musical track of the film. He appears on-screen several times as a prescient magician. Our footage of him playing piano at MoMA, in great close-up, is probably the last footage ever shot of him before he dies in 2006." Even the briefest of appearances by the Judson Dancers, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Robert Morris, and Robert Rauchenberg, are expertly timed to heighten our sense of the radical experimentation afoot in New York's Greenwich Village of the early 1960s.

Schneeman's Water Light/Water Needle (1966), also seen in the film, was performed at St. Mark's Church in the Bowery, and from there moved to the derelict Havemayer Estate in Mah-Wah, New Jersey. Nitoslawska is quick to point out that, "In the film the work is seen to be about gravity and it's defiance. A recurring theme in the film. The bodies horizontally float across space, like drawings in motion. Acts of Perception, the crazy B&W sequence with people crawling on the ground completes the triptych of works that sprang from Carolee's Judson years." As with Meat Joy, Water Light/Water Needle was performed by several Judson dancers and artists. During this period, Carolee also worked on numerous occasions with Lucinda Childs, Philip Corner, Malcolm Goldstein, Deborah Hay, and Elaine Summers. "In the 1960s, people didn't pay that much attention to credits," says Nitoslawska, "so their names don't appear on the works."

I was curious why we never see Charlotte Moorman in the film, an artist and musician whom Schneemann "was very fond of", though we do see Schneemann performing Up To And Including Her Limits (1973-76) for the fist time in The Avant-Garde Festival that had been curated by Moorman. Schneemann answered me anecdotally: "In the Moorman Avant-Garde Festival, each artist was given an empty, rather dirty boxcar in a line at Grand Central Station ... so, we couldn't say it was an exhibit, but something more freeform and chaotic, which was truly uniquely Charlotte's magical system for unpredictable configurations. I participated in many of her Avant-Garde Festivals, and it was I who encouraged Charlotte to be shamelessly nude as she played her cello. When she had an image of descending from a low balcony on a rope harness holding her cello, I thought the image could be Rubinesque. I wrapped her in a sheet which would gradually unfold and fall away as she descended. So she started out as a rather shy southern girl who was afraid to show her body, but once the sheet had fallen away she said 'Wha-Carolee, that surely was a delicious feeling.'"

Breaking the Frame also includes documentation of the iconic 1975 performance, Interior Scroll, arguably the most stunningly confrontational act of artistic-feminist dissent waged in the name of women taking back possession of their bodies from the representation and legislation of men. Nitoslawska's handling of the documentation likely required the most delicate diplomacy in the entire film. "The original performance was filmed by Dorothy Beskind," Nitoslawska tells us. "However, this material has never been released by her(!). I initially regretted that we wouldn't have access to these moving images. However, in retrospect, this limitation became a blessing, as is often the case. We 'animated' the stills of Interior Scroll, photographed beautifully by Anthony McCall, and avoided the predictability so often found in filmed documentation of performances. During the making of the film I realized that stills can render the spirit of a performance more accurately than film can. A good still is both a synthesis and an interpretation. Beyond its role as a 'record', it's an 'open work', in Umberto Eco's meaning of the term. Interior Scroll is a powerful work, an early Schneemann manifesto. Dramatic, vital and central to Schneemann's oeuvre, we sought to render its full resonance."

From Interior Scroll, Nitoslawska jumps a span of some thirty years to include the recognition that Schneemann has garnered, along with her many significant artist-feminist peers, at the historical WACK exhibition (2007), where we see many of the notable women artists of Carolee's generation. It's a segue that both underlines the importance of Interior Scroll to feminist art history and acknowledges Schneemann as among the earliest and most visible women activists in the ranks of second-wave feminism.

Although her first imperative was to craft a temporal monument to one of the 20th Century's most pivotal and radical artists, Nitoslawska wishes to remind us that her film is also about film. "In one of my first texts in the film I provide a key to both Schneemann's work and to my formal approach as a filmmaker: Gestalt...collage, montage, a continuous movement of corresponding pieces, breaking in and out of each other, fluidly superimposing, spinning in time." This isn't to say that Nitoslawska competes with her subject. If nothing else, she demonstrates that she is of a mind with Schneemann--that their work is entirely sympatico. "When I ask Carolee what she means by 'inside', 'outside', she replies: How to describe it...you know the proportionate rhythms within the forms, like no two images can just go together and why...because it's inexplicable! These are the last lines of the film." Lines that also summarize the defining principles guiding the entirety of this landmark film.

- www.huffingtonpost.com/

Creator of such acclaimed works as the performance Meat Joy and the film Fuses, for decades the artist Carolee Schneemann has saved the letters she has written and received. Much of this correspondence is published here for the first time, providing an epistolary history of Schneemann and other figures central to the international avant-garde of happenings, Fluxus, performance, and conceptual art. Schneemann corresponded for more than forty years with such figures as the composer James Tenney, the filmmaker Stan Brakhage, the artist Dick Higgins, the dancer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, the poet Clayton Eshleman, and the psychiatrist Joseph Berke. Her “tribe,” as she called it, altered the conditions under which art is made and the form in which it is presented, shifting emphasis from the private creation of unique objects to direct engagement with the public in ephemeral performances and in expanded, nontraditional forms of music, film, dance, theater, and literature.

Kristine Stiles selected, edited, annotated, and wrote the introduction to the letters, assembling them so that readers can follow the development of Schneemann’s art, thought, and private and public relationships. The correspondence chronicles a history of energy and invention, joy and sorrow, and charged personal and artistic struggles. It sheds light on the internecine aesthetic politics and mundane activities that constitute the exasperating vicissitudes of making art, building an artistic reputation, and negotiating an industry as unpredictable and demanding as the art world in the mid- to late twentieth century.

An Interview with Carolee Schneemann

From: Wide Angle Volume 20, Number 1, January 1998 Carolee Schneemann is a painter, filmmaker, and performance artist who began making films at twenty-six. Her filmic work includes Viet Flakes (1965), Fuses: Part I of Autobiographical Trilogy (1964-67), Plumb Line: Part II of Autobiographical Trilogy (1968-71), and Kitch's Last Meal: Part III of Autobiographical Trilogy (1973-78). In addition to her artworks, she has published several books including More Than Meat Joy: Complete Performance Works and Selected Writings (1979), ABC, We Print Everything - In The Cards (1977) and her feminist theory of art history, Cézanne, She Was A Great Painter (1974). Her forthcoming publications are Body Politics: Notes and Essays of Carolee Schneemann edited by Jay Murphy for MIT press and a selection of her letters edited by Kristine Stiles for John Hopkins University Press.

Fuses is a sexually explicit film shot by both Carolee Schneemann and her lover, Jim Tenney. Schneemann not only employs an experimental production strategy; she also engages the material properties of film by baking it, painting it, and making its tenuous structure visible (such as including splices as visible facets of the film's montage). Her camera does not follow any systematic, narrative ordering. Rather the body interrupts the frame, avoiding diegetic storytelling and following an idiosyncratic pulse of gesture and musicality.

The film explores heterosexual sex from a variety of vantage points, disturbing the formulaic imaging of sex found in Hollywood cinema. In Fuses the sexual act is not driven by a sequence of events or in service of a linear plot. Instead, sex is shown as a continuous and spontaneous activity between two people. Their relationship to one another is determined by the dynamics of physical coupling rather than individual character development or extenuating social circumstance.

The exhibition history of Fuses is quite remarkable and underscores the film's radical nature. In 1969, it won a Cannes Film Festival Special Jury Selection prize and has had regular public screenings since its completion. Yet, it continues to be a controversial work. In Moscow, twenty years after winning at Cannes, it provoked a small riot and was censored for pornographic content.

I interviewed Carolee Schneemann on March 28, 1997 in her loft in New York City.

Kate Haug: To refresh you on my project, I am specifically studying Fuses (1964-67), because I am looking at sexually explicit work made by women around the time of the women's movement. While I was watching Fuses the other day, I was struck by its beauty. It is so pivotal, for many reasons, in the history of experimental filmmaking. But, because it deals with sex, it has been left out of avant-garde film history and not really addressed by feminism. Is sex still the domain of men? Is that why it is so problematic for women?

Carolee Schneemann: Explicit sexual imagery propels the formal structure of Fuses. Initially, it was clear to me that people were so distracted by being able to have a voyeuristic permission to see genital heterosexuality that it would take them -- if they ever came back to see it again -- many showings before the structure was clear: the musicality of it and the way it was edited. Fuses is very formal in how it is shaped; that was crucial to making it have a coherent muscular life. Visualized erotic, active bodies deflect the very structures which shape montage: viewers are distracted by the simultaneity of perceptual layers Fuses offers.

Which is parallel to my own historic position. All my work evolves from my history as a painter: all the objects, installations, film, video, performance -- things that are formed. But the performative works -- which are one aspect of this larger body of work -- are all that the culture can hold onto. That fascination overrides the rest of the work. It is too silly, but it is still kind of a mind/body split. If you are going to represent physicality and carnality, we can not give you intellectual authority.

KH: As an artist, how do you see the work functioning beyond the sign of the body in terms of its formal structure?

CS: Well, it is a risk, but...

Artist Carolee Schneemann talks about her dance experiments with the revolutionary Judson Dance Theater

Carolee Schneemann, Meat Joy Photograph: Al Giese

Carolee Schneemann talks about her time with Judson Dance Theater at Danspace Project on September 21 and 22. In the program, held in conjunction with Platform 2012: Judson Now, Carolee Schneemann talks about famous works like Meat Joy, along with some of the dancers she adored: Deborah Hay, Ruth Emerson and Lucinda Childs.

In the ’60s, Carolee Schneemann’s work evoked a similar response to what many multidisciplinary artists experience today. Was she making dances? Happenings? Paintings? (It was, of course, a combination.) On Friday 21 and Saturday 22, Platform 2012: Judson Now hosts two evenings with Schneemann, the visual artist whose groundbreaking movement works explore the body, sexuality and gender. In this Danspace Project program, Schneemann will present newly edited archival films of her works Meat Joy (from 1964, it famously involved fish, chicken and sausages), Water Light/Water Needle (originally shown at St. Mark’s Church in 1966) and Snows (an anti–Vietnam War theater piece from 1967), as well as a live performance of Lateral Splay, first performed at Judson Church in 1963. Schneemann spoke about how dance entered her life.

Time Out New York: I really enjoyed hearing you speak at Movement Research’s Judson anniversary program in July.

Carolee Schneemann: It was wonderful, wasn’t it? What is it about that space? You get the feeling of its mixed religious and cultural identity?

Time Out New York: Yes—how the two can coexist and, maybe, how art is a religious experience.

Carolee Schneemann: I think so. In a very nondenominational way, you can feel the connection there.

Time Out New York: What is Lateral Splay?

Carolee Schneemann: It’s a work based on energies from action painting in which a group of 12 to 15 participants—they might not necessarily be dancers—are trained in a set of very intense exercises to use their bodies as exploding particles. It’s a running work—as fast as possible. In one section, the knees are bent, and in another section, the arms are extended rather precariously. We practice that together and build a set of contact improvisation exercises so [the performers’] sense of self-dynamic in the space is increased, as well as their sense of contacting and locating each other, which will result in grabs and falls. It’s a good work to present in small, bursting units.

Time Out New York: Is it dangerous?

Carolee Schneemann: Yeah. But it seems more dangerous than it really is. The more you practice it, the less dangerous it is.

Time Out New York: How will you find performers for Lateral Splay?

Carolee Schneemann: The word is going out into the dance and movement communities. It’s a surprise. We all come together and see who really wants to do this and who can commit to the time and energy of it. I’m just requesting a variety of shapes, sizes, genders and races.

Time Out New York: How did you come up with the movements?

Carolee Schneemann: I am essentially a painter. And the energy of perception through a variety of forms has always triggered my sense of a whole-body musculature through the eye. How dynamic can the form be? So I was turning from elements in painting to the human body. I don’t know if that explains it, but that’s some aspect of what informs the energy. My paintings—and now my recent sculpture installations—are always all about motion and momentum. With Lateral Splay, what I want to do that I think will really be fun is to have a projection of it—so you have a virtual great big image—and then to explode that with real action. So there will be that juxtaposition. That is the second part of the evening. The first part will be showing unusual videos of mine that are involved in motion.

Time Out New York: Like what?

Carolee Schneemann: Some of the historic images that I’ve remastered: Water Light/Water Needle.

Time Out New York: What was the idea behind it?

Carolee Schneemann: It’s based on my having been in Venice and the amazing sense of merging and melting between sky and water and questioning the dimensional weight of the human body between these illusory, shifting essences and tonalities. What’s sky, what’s water and how do you carry your own gravitational weight? It’s about gravity and an aspect of almost floating the body horizontally across space. [Water Light/Water Needle was conceived as an aerial work for ropes that would be rigged across the canal at San Marco.] I had an engineer help me rig ropes—some of them were about 25 feet—across the entire space of St. Mark’s. It was in the parsonage room, not the big room. The ropes required, more than I ever thought, a great deal of calluses and muscle memory; initially, it was [based on] a series of drawings of bodies almost floating across space on the ropes, and the ropes were at three levels and crisscrossed—some were very high, some were medium height and some were rather low. The instructions for the work have to do with the motion between the ropes; also, every time you come up on another person, your intention has to change and absorb theirs. We did it outside in New Jersey at the old estate of the Havemeyer’s, and that was very interesting. I love to perform outside. I started as a landscape painter, so “outside” is an affinity of potentiality. It was beautiful, it felt so good. And that footage has not been properly edited until this year, so I’ll show that.

Time Out New York: And you’re also showing a reedited version of Meat Joy?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes. Meat Joy was a vision of sensuous interaction that I conceived of for an invitation to perform in Paris, for Jean-Jacques Lebel’s experiments in the First Festival of Free Expression. Once I had that invitation, I began imagining a very sensuous interaction between the participants and visceral materials: It would be fish and chickens and sausages. So I created a whole score of what I would call movement parameters; there would be movement parameters within which improvisation and unexpected aspects would develop. There was a corps of eight performers and what I call the “director/reality” figure. The woman who kept the clock and could time sequences and who would, at the right point—after there was a movement collapse from an impossible circle movement—introduce the trays of chicken, fishes and sausages.

Time Out New York: Why did you want to use the food as your material?

Carolee Schneemann: They’re very basic to still life. They’re visceral. In our tradition, they’re always suggestive of luscious surface, domestic organization—in the old Dutch paintings, there are piles of fish being brought in from nets, and then they go to these very appealing tables with fruits, vegetables, fish and chicken. I wanted to activate an art-historical iconography that’s wet and weighty and smelly and bring it into my extension of painting traditions.

Time Out New York: I wish you could bring that back. I suppose St. Mark’s Church would be against that.

Carolee Schneemann: [Laughs] The [Judson] minister at the time, Howard Moody, was so wonderful. Meat Joy was performed in the center of Judson church, and the whole sanctuary really stunk of the fish, but Pastor Moody was so gracious. He built a sermon around it.

Time Out New York: You started making performance works well before the first performance of Judson Dance Theater, right?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes. The first performance I did was in Sidney, Illinois, outside of Champaign-Urbana where [composer] Jim Tenney and I had graduate fellowships. A tornado came through—we lived in a really fragile little shack in the only woods that we could find within 20 miles of the university, and so trees came down and the little stream bed flooded. One of the trees crashed down through our kitchen and our landlord was 80 years old. We knew this was a disaster, and we had no idea what to do, but my cat Kitch studied this tree in the sink in the smashed window and immediately saw it as a doorway: a magical entrance-exit. She walked along the branch of the tree from the sink outside to the field, and I said, That’s what I want to do. I want to have that inside-outside dynamic. So smooth and connective. So the first performative work was to invite people, friends from the university, and give them cards to be within the altered landscape, to be in the mud, to be in the water, crawl under the trees and over the trees. I didn’t know exactly what I was doing, but I was intensifying the process of painting by putting the body where the brush had been. It’s something like that.

Time Out New York: Do you see bodies as colors?

Carolee Schneemann: I did when I worked with the Judson group. Lucinda Childs was yellow and golden, and Deborah Hay was sort of rosy and red tones, and Ruth Emerson was my blue. But the thing that was very unexpected was that some of my colors wouldn’t turn up when I needed them. They were not available. They had another job. [Laughs] I can’t go on without the yellow! It was funny. I also had very vivid drawings and sensations about aspects of the movement each of those bodies seemed to inhabit.

Time Out New York: In what way in terms of someone like Lucinda Childs?

Carolee Schneemann: With Lucinda, I always created something very formally structured and unified. Deborah was sort of my alter ego because I didn’t do performance yet, so she had more wild, sexy contact actions happening. For Ruth Emerson, with those incredible legs, I always conceived of works having to do with elongation in space. And, of course, Meat Joy evolved out of the earlier Judson pieces. But I was still painting and doing installation work at the same time. Then I began to use my own body in Eye Body, the visual sequence of self-transformations for camera.

Time Out New York: When did you first start using nude bodies?

Carolee Schneemann: I used my nude body in Eye Body in ’63 [in which Schneemann merged her own body with the environment of her painting/constructions]. That was part of physicalizing a room that was energized and very free in terms of, again, addressing this history of the nude and revitalizing it. I might as well mention this—in these years, one of my jobs was as an artist’s model. I wanted to see if I could really interfere, in my literal way, with that tradition of the passive nude and the painter, always a guy—and always an older guy—telling the students how to look. So that was one contrary influence. Also Pop Art where the women were so mechanized. That influenced my making Fuses, the heterosexual erotic film [of collaged and painted sequences of lovemaking between herself and James Tenney]. We were definitely naked. [Laughs] Part of the presumption of addressing those bodies came from my cat Kitch. She had such a shameless appreciation for our being lovers. And she would always come close and be very discreet—we would never see her staring at us unless we suddenly opened our eyes.

Time Out New York: Why did you start working with dancers? Was it in reaction to something you saw? Or was it really a conscious way to extend your painting?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes, and I guess I always had a lot of dance feeling personally. I admired so much what they could make and do, and I felt a bit like an interloper, but I wanted to try and put some of the kinetic drawings I was making into actual bodies. I guess I had already been in [Claes] Oldenburg’s Store [Days], and that was a huge influence: It was being inside someone’s visionary material. It was so wonderful at how it was coming from a painterly, almost deformation, of potential structure. It was a sense at the time of an exploded canvas. Or what I would call a sensory arena. To go into real time and dimensional space.

Time Out New York: What did that show you about your work and your ideas?

Carolee Schneemann: It just confirmed that one could go further with that and use more varied aspects of space and material. But a lot of it is very instinctual: Up to and Including Her Limits [1973–76] starts by watching my friend, a tree surgeon, hanging his harness and cutting the tree limbs. [In this reaction to Jackson Pollock’s painting process, Schneemann is suspended in a tree surgeon’s harness on a three-quarter-inch Manila rope that she raises or lowers manually in order to draw.] Because of Water Light/Water Needle, I recognized the three-quarter-inch Manila rope and thought, I can work with that. And the harness is a very interesting, also antigravitational source of suspension and momentum. So even if it’s intuition, intuition is everything that you know and have ever done. It’s not blind, but it doesn’t have a predetermination.

Time Out New York: Was it fairly easy to find willing dancers and willing bodies at Judson?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes! Because we were all in the initial group and the premise was to help each other and be available. And I was thrilled to be in the running piece or the standing-and-chanting piece. We all wanted to give whatever somebody might need. For Meat Joy, the performers were all, with maybe one exception, untrained people that I found in bars and on street corners.

Time Out New York: Why did you want them untrained?

Carolee Schneemann: I wanted to escape the dancer’s sense of physical construction and predictive motion and momentum. I wanted people that could just fling themselves into space and feel an adventurous confidence, and I had reached a point with trained dancers where that was too much of an imposition coming from me. I wasn’t a dancer, and some of them felt that the work was not safe for them or too messy. They’re highly trained to break the forms that they’d been trained in. And I was coming in from a different direction. It was painterly and gestural. In the ’60s, none of us knew that this would matter to anybody very much. [Laughs] I think you never know. You kind of know, but it’s so uncertain. There’s a crucial transformation underway. Will it enlarge? It certainly has more than enlarged. The concept of performance is viral. It can be anything, anything.

Time Out New York: What do you think of that?

Carolee Schneemann: Well, I can’t say because anything that I say becomes exaggerated in its reception. I guess everyone should be encouraged. [Laughs slyly]

Time Out New York: Had you had any training in dance yourself?

Carolee Schneemann: Not really, but I always danced before I painted to Bach or to rock & roll to really feel energized. It was sort of a private, secret thing. I’d close the door, put the music on and go to the studio to paint. I kind of still do it.

Time Out New York: Why is Judson Church, as a place, special to you?

Carolee Schneemann: Well, it’s exquisite. The proportion, the architecture—it’s a beautiful, almost Romanesque, structure and it has such enriched memories. I’m sure it’s like this for most dancers and performers: When you inhabit and physicalize a space and bring something to life in it, it stays with you—it’s almost like a habitation. So I have that with every place where I was able to realize a very strong work. I think especially Judson, because the proportion is so beautiful. No matter how long I’ve been away, it’s a home base.

Time Out New York: Do you consider yourself to be a choreographer?

Carolee Schneemann: Sure. But with a parenthetical: a choreographer as extending principals of media. I could say that Robert Whitman is a choreographer; Oldenburg, for sure. Maybe Red Grooms. Or let’s say there are choreographic developments or aspects, but they’re not choreographers the way a choreographer would justifiably define herself or himself.

Time Out New York: Could you describe your choreographic process?

Carolee Schneemann: They all start with highly energized drawings of bodies in action or activities, and then if the drawings seemed present or intense enough, I would bring them to the Judson group and see what might come of it. They would study the drawings, and I would begin to choreograph the movements they adapted from the drawings. I would work with duration, position and relationship to the space, which wasn’t always the dancer’s concern at all. For instance, in the Judson gym, we had two basketball hoops and I thought they functioned very strongly as dimensional material—almost as a head and shoulders hanging up there in space—so I was concerned with how they related to our movements, as well as the radiators—things like that. The dancers didn’t pay those any mind. Whereas wherever painters were doing happenings or events, the whole space was seized with energy.

Time Out New York: What are you working on now?

Carolee Schneemann: I’m doing kinetic sculpture within projection. I saw these shapes—I call them flange—and they’re three and a half or four feet high. I’m not sure what they resemble; maybe wings or leaves. And then I build them out of wax and they’re poured in a foundry. They’re burnt into aluminum shapes, so each original is destroyed and these aluminum sculptures are motorized, with the motor in a computer chip turning them. Three or four of them move from the same base and precariously twist backward or forward or go slowly around and they extend to the wall on an extended kind of arm. They move at 6 RPM, and they’re moving within a projection of a fire that burnt their shapes into the aluminum, so they’re dynamic and they’re big. You walk right into it.

Interview with Carolee Schneemann

What was it like when you were entering the art world in the ‘60s?

The New York art world in the ‘60s was very small and intense, and you could approach artists that you knew were going to be significant. I could go talk to John Cage, be the secretary for Edgard Varèse, go to Philip Guston’s studio and hang around. We could go to the openings of older artists, and it was easy, convivial, a tremendous source of information.

Who were your influences from that period? How did women fit into the art world of the time?

It’s an interesting question because women didn’t really get to coalesce and discuss what they were doing until the early ‘70s. I found that the women artists were all constellated around the men, they rarely had exhibits despite how significant I found their work. For instance Joan Mitchell, who was a great influence on me rarely exhibited. Since I started out as a painter who concentrated on landscape, I was impressed by the spaciousness of her work in which each paint stroke was an event, energizing perceptual time.

Once I arrived in New York City, I met poets who appreciated my work, like Robert Kelly, Jerome Rothenberg, David Antin. The discussions and energy between us was vital, though even here the younger women poets had a peripheral participation. Pollock’s overall canvases were a direct influence, as was the force field of De Kooning, and of course Cézanne was my major inspiration for the construction of form in space. My influences tend to be complex: Antonin Artaud, De Beauvoir, all the way back to classical inspirations of Focillon.

Of my contemporaries, Brakhage the filmmaker, but most of all my partner James Tenney, who appears in so many of my film and performance works. Tenney was studying Ives and Webern who became huge influences on my thinking about visual events in time. By 1962 I began to choreograph for the Judson Dance Theater. Our aesthetic affiliations were all very delicious and interconnected – just about any figure that might come to your mind would be someone whom we all knew, that we went dancing with or smoked dope with.

How did female artists start to coalesce? Was there a sense of common purpose?

There was an interesting period of separatism that we tend to forget. In the early ‘70s consciousness-raising was a developing discipline for women; we were analyzing our exclusions and marginalizations from cultural traditions. There was a period when the men wanted to discuss these issues with us, and we realized that they were just going to try to solve our problems and analyze them, and it would not be successful. And so separatism was necessary for consciousness-raising; women started art galleries, started publishing feminists texts, revised standard art history, began communities together.

While there was a sense of common purpose, there was often competition and conflict concerning the significance of issues—there were hierarchies within feminist analysis and formulation.

How has the community changed since that time in the ‘70s?

It’s huge, it’s expansive. Our community is richly various. Women have major positions in art galleries and museums, in publishing and all areas of cultural investigation. Many artists disappeared, which is interesting to research, to go through the early reviews and articles to see how many have sustained themselves and how many have left the art world. That’s true for the male artists as well, it was not an easy emergence for any of us.

Do you have any sense of continuity between that period and the present?

I don’t know the answer to that because there’s so much remarkable work coming from painters who established their concentration in the ‘70s and ‘80s and more recently. There’s also a great deal of indulgent, simplistic work, done by some younger women, as if just being female addresses bigger principles. And it doesn’t.

It also has to do with the proliferation of women artists. There’s so much to look at and think about that it’s hard to grasp a continuing moment, a continuing attention. I can’t say what other artists should be thinking about, except that their commitment and concentration still needs to be rigorous, deep, troubled, unpredictable and pleasured.

How has your own work developed?

I don’t want to be locked in the work I made in the ‘60s and ‘70s—those earlier concepts, which provide academics with a way of organizing a syllabus. I’m very excited and filled with joy when viewers and writers look at recent work and can analyze it and understand it in terms of what went before. I’m always desperate to show my more recent work; installations and video projections that are rarely seen, but are often greatly appreciated when they do enter the cultural discussion.

I’m looking ahead and carrying forward the principles and elements of the earlier work. I don’t consider my work a “career.” I definitely don’t have a “practice”: a practice belongs to a dentist or a violinist. A practice implies a kind of perfectibility, which I don’t seek.

www.artlog.com

Carolee Schneemann: Carnal VisionaryThe New York art world in the ‘60s was very small and intense, and you could approach artists that you knew were going to be significant. I could go talk to John Cage, be the secretary for Edgard Varèse, go to Philip Guston’s studio and hang around. We could go to the openings of older artists, and it was easy, convivial, a tremendous source of information.

Who were your influences from that period? How did women fit into the art world of the time?

It’s an interesting question because women didn’t really get to coalesce and discuss what they were doing until the early ‘70s. I found that the women artists were all constellated around the men, they rarely had exhibits despite how significant I found their work. For instance Joan Mitchell, who was a great influence on me rarely exhibited. Since I started out as a painter who concentrated on landscape, I was impressed by the spaciousness of her work in which each paint stroke was an event, energizing perceptual time.

Once I arrived in New York City, I met poets who appreciated my work, like Robert Kelly, Jerome Rothenberg, David Antin. The discussions and energy between us was vital, though even here the younger women poets had a peripheral participation. Pollock’s overall canvases were a direct influence, as was the force field of De Kooning, and of course Cézanne was my major inspiration for the construction of form in space. My influences tend to be complex: Antonin Artaud, De Beauvoir, all the way back to classical inspirations of Focillon.

Of my contemporaries, Brakhage the filmmaker, but most of all my partner James Tenney, who appears in so many of my film and performance works. Tenney was studying Ives and Webern who became huge influences on my thinking about visual events in time. By 1962 I began to choreograph for the Judson Dance Theater. Our aesthetic affiliations were all very delicious and interconnected – just about any figure that might come to your mind would be someone whom we all knew, that we went dancing with or smoked dope with.

How did female artists start to coalesce? Was there a sense of common purpose?

There was an interesting period of separatism that we tend to forget. In the early ‘70s consciousness-raising was a developing discipline for women; we were analyzing our exclusions and marginalizations from cultural traditions. There was a period when the men wanted to discuss these issues with us, and we realized that they were just going to try to solve our problems and analyze them, and it would not be successful. And so separatism was necessary for consciousness-raising; women started art galleries, started publishing feminists texts, revised standard art history, began communities together.

While there was a sense of common purpose, there was often competition and conflict concerning the significance of issues—there were hierarchies within feminist analysis and formulation.

How has the community changed since that time in the ‘70s?