Otac, kum, frontmen i lijevo krilo novog filipinskog filma.

Filmovi mu traju i po 11 sati.

Čudesan opus.

mubi.com/cast_members/65721

Century of Birthing (2011)

Stories about a Christian religious cult and a self-involved filmmaker, are brilliantly intertwined in Lav Diaz's newest film, premiered at the Venice Film Festival, 2011. Century of Birthing also weaves different types of filmmaking together (documentary, fiction, film-within-a-film) to create a profound 21st-century exploration of the value of art, belief and commitment. Lav Diaz was present throughout the weekend to discuss his work with curator George Clark and critic May Adadol Ingawanij.

The Films Of Lav Diaz

Posted by Just Another Film Buff under

Lavrente Indico Diaz is a multi-awarded independent filmmaker who was born on December 30, 1958 and raised in Cotabato, Mindanao. He works as director, writer, producer, editor, cinematographer, poet, composer, production designer and actor all at once. He is especially notable for the length of his films, some of which run for up to eleven hours. His eight-hour Melancholia, a story about victims of summary executions, won the Grand Prize-Orizzonti award at the Venice Film Festival 2008. His work Death in the Land of Encantos also competed and represented the country at the Venice Film Festival documentary category in 2007. It was granted a Special Mention-Orizzonti. The Venice Film Festival calls him “the ideological father of the New Philippine Cinema”. As a young man, Diaz was particularly inspired by Lino Brocka’s Maynila: Sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag, describing it as the film that opened his eyes to the power of cinema. Ever since then, he made it his mission to make good art films for the sake of his fellow Filipinos. His body of work has led critics to call him both an “artist-as-conscience” and the heir to Lino Brocka. Diaz has also been compared to other great Filipino directors such as Ishmael Bernal, Mike de Leon and Peque Gallaga, whose films examined the ills of Filipino society (Image Courtesy: Rotterdam Film Festival, Bio Courtesy: MUBI)

Filipino director Lavrente Diaz is a very versatile artist. He started out as a guitarist (He recently released a music album to accompany his latest film), then wrote plays and short stories for television (a period he seems to hate, as is made clear in his works), later started writing poems (the poems that feature in his films are written by him) and then, in the early 90s, decided that he’ll be a professional filmmaker. The later films of the director present the same kind of problem to both commercial multiplexes and film festival screens – their length. His last four feature films have a total run time of around 36 hours! Diaz believes the long length of his films is an extremely crucial part of his aesthetic and radically alters the way in which the audience converses with his films. There is another specific problem in screening Diaz’s films world wide. That he is a very “Filipino” filmmaker. All his works are deeply rooted in the country’s history and politics. Any attempt to view the films in a de-contextualized manner is only futile. That makes Diaz one of the most uncompromising of directors working today. Diaz’s greatest ambition, as it seems, is to change the Filipinos’ (and rest of the world’s) perspective of their country and culture (He tells: “For me, the issue is: if you’re an artist, with the state the country is in you only have one choice – to help culture grow in this country. There’s no time for ego, you have to struggle to help this country. Make serious films that even if only five people watch it, it will change their perspective. You may make big box office but what do the people get out of it?”).

What is really striking about Lav Diaz is how vocal and frank he is about his ideology and his works. Most of modern mainstream auteurs and even festival regulars shy away from commenting on their work or on the ideas they present. Some of them bury their political concerns so deep within their films that they may simply be overlooked. Diaz, on the other hand, is like an open book. In all his interviews, he is always willing to discuss his films and explain what they deal with. None of this actually dilutes the impact of the films or the complexities they contain. Instead, it only opens up a wider and more pertinent band of response to the film. Furthermore, Diaz is also very transparent about his political views and even his personal life (His story is exactly the kind of success yarn pseudo-liberal Hollywood studios are looking for. But one sure has to appreciate the man for what he’s gone through and what he’s become). To say that he feels strongly against the Ferdinand Marcos’s rule of The Philippines till about two decades ago would be an understatement (“He siphoned the treasury as well. He got everything. No matter what they say, he stole everything – the money, our dignity. It is true. Marcos is an evil person. He destroyed us. The hardest part was that he was Filipino”). Diaz is also very optimistic about the role artists play in a political revolution and this belief directly manifests in his films in the form of artist figures present in the narrative.

I’d say that Diaz’s aesthetic stands somewhere in between Contemporary Contemplative Cinema and conventional documentary. Like the former, he prefers long takes shot from at a considerable distance, avoids the use of background music, includes stretches of “dead time” in his narrative and relies on mood and atmosphere more than exposition or psychoanalysis. He employs parenthetical cutting that allows a shot to run for more duration than the length of the principal action, but cuts soon enough to avoid the shot to parody itself. Unlike Contemporary Contemplative Cinema, there are long stretches of dialogue in the vein of early Nouvelle Vague films and the politics the films deal with are much more concrete. All his recent features have been shot in black and white as if they are historical documents and as if the vitality of its characters has been sucked out. His use of direct sound goes hand in hand with his use of digital video, which enables him to experiment with long shots. It is only in a blue moon that he uses close-ups and all his medium and long shots come across as clinical observations of his characters’ lives. That doesn’t mean his films lack empathy or compassion. But the way he generates them is more distilled and uncontrived. He composes in deep space and allows the viewer to get a complete sense of the film’s environment and time. He says: “There’s no such thing as the audience in my work. There’s only the dynamic of interaction. And in time, that dynamic will grow. The greatest dynamic is when people want to see a work because of awareness and they want to experience it; and in so doing, they may be able to discover new perspectives or just put these perspectives into a greater discourse.”

(NOTE: I’ve written here about all the films of Lav Diaz that I could get my hands on. However, I haven’t been able to see any his earlier works or his short films. I’ll append the entries for the missing films here once I get to see them)

Serafin Geronimo: Ang Kriminal Ng Baryo Concepcion (Serafin Geronimo: The Criminal Of Barrio Concepcion, 1998)

Diaz’s debut, Serafin Geronimo: Criminal of Barrio Concepcion (1998), even without the burden of its successors, is a poorly made piece of cinema. It’s got all the trappings of a bad student film – laboured acting, ill-advised cuts, unwarranted zooms and an occasionally bombastic score – that only worsen its low production values. Very loosely based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Serafin Geronimo chronicles the titular criminal’s act of sin and his subsequent confession and redemption. Diaz chooses to externalize the moral conflict of the protagonist through a dental infection whose pain seems to grow unbearable. Additionally, there’s a lot of gratuitous violence – graphic and described – in the film (even in the censored version) that underscores the savagery of the world Serafin (Raymond Bagatsing), like Hesus, is caught in. Evidently, like the Russian author, the film wants to observe human suffering in all its brutality. But what the film does not seem to understand is that human suffering can’t be captured on film by merely recording mutilated bodies or the physics of their destruction. Such documentation must attempt to record the death of the soul – the internal through the physical – as well (Compare this film with the sublime, genuinely Dostoevsky-ian passage depicting Kadyo’s demise in Evolution). However, the scenes at the countryside, set in the past, are executed with certain affection and restraint. Diaz pushes his political ambitions to the background as the quest for personal justice and redemption takes precedence here over national issues. The use of curious, hand held camera and the staging of action in deep space during indoor scenes are few of the traits that would be carried over and refined in Diaz’s later, superior works.

Diaz’s debut, Serafin Geronimo: Criminal of Barrio Concepcion (1998), even without the burden of its successors, is a poorly made piece of cinema. It’s got all the trappings of a bad student film – laboured acting, ill-advised cuts, unwarranted zooms and an occasionally bombastic score – that only worsen its low production values. Very loosely based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Serafin Geronimo chronicles the titular criminal’s act of sin and his subsequent confession and redemption. Diaz chooses to externalize the moral conflict of the protagonist through a dental infection whose pain seems to grow unbearable. Additionally, there’s a lot of gratuitous violence – graphic and described – in the film (even in the censored version) that underscores the savagery of the world Serafin (Raymond Bagatsing), like Hesus, is caught in. Evidently, like the Russian author, the film wants to observe human suffering in all its brutality. But what the film does not seem to understand is that human suffering can’t be captured on film by merely recording mutilated bodies or the physics of their destruction. Such documentation must attempt to record the death of the soul – the internal through the physical – as well (Compare this film with the sublime, genuinely Dostoevsky-ian passage depicting Kadyo’s demise in Evolution). However, the scenes at the countryside, set in the past, are executed with certain affection and restraint. Diaz pushes his political ambitions to the background as the quest for personal justice and redemption takes precedence here over national issues. The use of curious, hand held camera and the staging of action in deep space during indoor scenes are few of the traits that would be carried over and refined in Diaz’s later, superior works.Hesus Rebolusyonaryo (Hesus The Revolutionary, 2002)

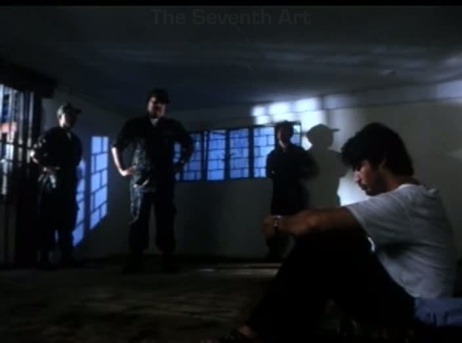

Hesus the Revolutionary (2002) is set in the year 2010 and follows the titular resistance fighter (Mark Anthony Fernandez) whose loyalty and ideology are put to test when he is ordered by the leader of the movement to kill his cell mates and is subsequently captured by the military. The most noteworthy aspect of the film is that Diaz does not set the film in far future or alter the mise en scène to make it seem futuristic. The fact that the architecture and geography look very contemporary indicates that there has been no progress for quite some time. Additionally, he uses pseudo-newsreels as prelude to the narrative. All these moves aid Diaz’s vision of establishing the future as a mere variant of the past and the present. His intention is to provide a critical distance between the audience and the story and hence make them reflect on how the same kind of events have happened in the past and are still happening. The chiaroscuro driven mise en scène through which the protagonist secretly moves seems to have been derived from American noir films. Diaz films his characters in moderately long shots and uses a techno soundtrack (by the band The Jerks) that enhances the dystopian sense overarching the film. Even while working within the limits of the genre (thereby using some of its conventions), Diaz manages to suffuse the film with themes that he would progressively be concerned with. However, Hesus the Revolutionary, in hindsight, is only the tip of a gargantuan iceberg.

Hesus the Revolutionary (2002) is set in the year 2010 and follows the titular resistance fighter (Mark Anthony Fernandez) whose loyalty and ideology are put to test when he is ordered by the leader of the movement to kill his cell mates and is subsequently captured by the military. The most noteworthy aspect of the film is that Diaz does not set the film in far future or alter the mise en scène to make it seem futuristic. The fact that the architecture and geography look very contemporary indicates that there has been no progress for quite some time. Additionally, he uses pseudo-newsreels as prelude to the narrative. All these moves aid Diaz’s vision of establishing the future as a mere variant of the past and the present. His intention is to provide a critical distance between the audience and the story and hence make them reflect on how the same kind of events have happened in the past and are still happening. The chiaroscuro driven mise en scène through which the protagonist secretly moves seems to have been derived from American noir films. Diaz films his characters in moderately long shots and uses a techno soundtrack (by the band The Jerks) that enhances the dystopian sense overarching the film. Even while working within the limits of the genre (thereby using some of its conventions), Diaz manages to suffuse the film with themes that he would progressively be concerned with. However, Hesus the Revolutionary, in hindsight, is only the tip of a gargantuan iceberg. Thanks to West Side Avenue (2001), clearly Lav Diaz’s first major work, we now know what will happen if the Filipino filmmaker takes to genre filmmaking. Diaz takes the standard policier, blows it to a size beyond what the text can handle and, in essence, brings to surface the mechanics of the genre. Constructed as a (seemingly endless) series of interrogations and recollections, a la Citizen Kane (1941), the film presents itself like a sphere without a centre. (Like Charles Kane, the relationship of all the characters to the dead boy at the centre of Diaz’s film – which is developed strikingly with a plethora of parallels – becomes the guiding device.) The procedure becomes so routine and schematic, aided to a large degree by the repetition of spaces and compositions, that the lead detective (Joel Torre) becomes something of a Melvillian zombie trudging through generic structures. But then, talking about Diaz’s film in terms of the genre is not half as justified as reading it from a national and auteurist perspective. Firmly planted in historical and geographical particulars – Filipino youth living in and around Jersey City during the turn of the century – the film takes up the issue of disappearing Filipinos – a sensitive idea that would be pursued further in other forms the later films – and examines the historical deracination and alienation that marks these young men and women. The relationship between the various characters with the killed teenager reflects their own conflicted relationship with their homeland. The film, itself, is somewhat (and slightly problematically) neo-nationalistic in flavour, gently appealing for cultural consciousness, integration and a “return to one’s roots”. The narrative mostly involves the investigation of the murder of one Manila teenager, If one moves beyond its precise sociological ambitions, one also discovers the flourishing of to-be-familiar stylistic (and narrative) devices: Scenes in master shots, montage of long takes, monochrome passages in. video and use of total amateurs. (Oddly enough, my favorite scene in the film is among the most uncharacteristic of Diaz’s cinema: a breakfast scene cut with verve comparable to Classical Hollywood). However, the most unmistakable authorial trademark of West Side Avenue is also the feature that attracts me most to Diaz’s work: the candidness and enthusiasm about his politics and political engagement, in general, as well as that rare faith in and love for cinema. That is why, towards the end of the film’s five hours, when the detective and the filmmaker – two professions seeking to discover truth – catch up with each other and restore the hitherto-absent heart of the film, you don’t if Diaz identifies with the detective or the filmmaker. He’s both.

Thanks to West Side Avenue (2001), clearly Lav Diaz’s first major work, we now know what will happen if the Filipino filmmaker takes to genre filmmaking. Diaz takes the standard policier, blows it to a size beyond what the text can handle and, in essence, brings to surface the mechanics of the genre. Constructed as a (seemingly endless) series of interrogations and recollections, a la Citizen Kane (1941), the film presents itself like a sphere without a centre. (Like Charles Kane, the relationship of all the characters to the dead boy at the centre of Diaz’s film – which is developed strikingly with a plethora of parallels – becomes the guiding device.) The procedure becomes so routine and schematic, aided to a large degree by the repetition of spaces and compositions, that the lead detective (Joel Torre) becomes something of a Melvillian zombie trudging through generic structures. But then, talking about Diaz’s film in terms of the genre is not half as justified as reading it from a national and auteurist perspective. Firmly planted in historical and geographical particulars – Filipino youth living in and around Jersey City during the turn of the century – the film takes up the issue of disappearing Filipinos – a sensitive idea that would be pursued further in other forms the later films – and examines the historical deracination and alienation that marks these young men and women. The relationship between the various characters with the killed teenager reflects their own conflicted relationship with their homeland. The film, itself, is somewhat (and slightly problematically) neo-nationalistic in flavour, gently appealing for cultural consciousness, integration and a “return to one’s roots”. The narrative mostly involves the investigation of the murder of one Manila teenager, If one moves beyond its precise sociological ambitions, one also discovers the flourishing of to-be-familiar stylistic (and narrative) devices: Scenes in master shots, montage of long takes, monochrome passages in. video and use of total amateurs. (Oddly enough, my favorite scene in the film is among the most uncharacteristic of Diaz’s cinema: a breakfast scene cut with verve comparable to Classical Hollywood). However, the most unmistakable authorial trademark of West Side Avenue is also the feature that attracts me most to Diaz’s work: the candidness and enthusiasm about his politics and political engagement, in general, as well as that rare faith in and love for cinema. That is why, towards the end of the film’s five hours, when the detective and the filmmaker – two professions seeking to discover truth – catch up with each other and restore the hitherto-absent heart of the film, you don’t if Diaz identifies with the detective or the filmmaker. He’s both.Ebolusyon Ng Isang Pamilyang Pilipino (Evolution Of A Filipino Family, 2004)

Running for almost eleven hours and twelve years in the making, Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004), which many consider to be Lav Diaz’s greatest work, is kamikaze filmmaking of the highest order. Mixing film and digital formats (which might be an economic decision), splicing the real with the surreal and weaving together documentary and fiction, Diaz concocts a glorious and flamboyantly self-reflexive film that slips seamlessly from one mode of discourse into another. The film’s central character is Ray (Elryan De Vera), a child found on the street by the mentally ill Hilda (Marife Necisito) and who goes on to live with another family of gold diggers. One could argue that Ray is the stand in for a whole generation of Filipinos abandoned by their “parents” and left stranded (Diaz himself calls Ray as the Filipino soul). Also central to the film is Hilda’s brother Kadyo (Pen Medina), who helps the resistance fighters by stealing ammunition from dead soldiers of the military. Interspersed among the sequences that drive this fiction are newsreels depicting rallies and riots against the then-existing Ferdinand Marcos regime, interviews of the legendary filmmaker Lino Brocka explaining political film movement during the Marcos rule and footage of artists reciting sappy, exaggerated and hilarious radio serials that everyone in the fictional world seems to be hooked to. Evolution of a Filipino Family is, as the title hints, a document – one that studies and critiques a whole era and suggests what’s to be done.

Running for almost eleven hours and twelve years in the making, Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004), which many consider to be Lav Diaz’s greatest work, is kamikaze filmmaking of the highest order. Mixing film and digital formats (which might be an economic decision), splicing the real with the surreal and weaving together documentary and fiction, Diaz concocts a glorious and flamboyantly self-reflexive film that slips seamlessly from one mode of discourse into another. The film’s central character is Ray (Elryan De Vera), a child found on the street by the mentally ill Hilda (Marife Necisito) and who goes on to live with another family of gold diggers. One could argue that Ray is the stand in for a whole generation of Filipinos abandoned by their “parents” and left stranded (Diaz himself calls Ray as the Filipino soul). Also central to the film is Hilda’s brother Kadyo (Pen Medina), who helps the resistance fighters by stealing ammunition from dead soldiers of the military. Interspersed among the sequences that drive this fiction are newsreels depicting rallies and riots against the then-existing Ferdinand Marcos regime, interviews of the legendary filmmaker Lino Brocka explaining political film movement during the Marcos rule and footage of artists reciting sappy, exaggerated and hilarious radio serials that everyone in the fictional world seems to be hooked to. Evolution of a Filipino Family is, as the title hints, a document – one that studies and critiques a whole era and suggests what’s to be done.

Diaz shoots almost exclusively in medium shots (to avoid any sort of manipulation, he says) and some of his compositions carry the air of evocatively rendered still life paintings. His soundtrack is even more remarkable and he edits it in such a manner that fiction regularly overflows into reality. Diaz throws in everything he’s got into this film. Examining a number of topics including commercialism versus art, the class struggle, art versus reality and the inseparability of past and present, Diaz creates a dense and incisive film that seems to announce once and for all what Diaz’s cinema is all about. At heart, Evolution of a Filipino Family is a film about resistance – political and cinematic. While Kadyo and the farmer army he works for exhibit their resistance by taking up arms against the military, Lino Brocka and his cohorts manifest theirs in cinematic terms. The link is very important, as Diaz himself has pointed out, since it is through the machinery of cinematic propaganda that the Marcos regime (as any totalitarian regime would) had reinforced its position among the Filipinos. If Hesus the Revolutionary set a fantastical revolutionary movement in the near future, this film uses the one that took place for real in the past. Diaz’s intention is not just to capture the spirit of the age, but, as in the previous film, to use this piece of history to study the present and understand the state of affairs.

Heremias (Unang Aklat: Ang Alamat Ng Prinsesang Bayawak) (Heremias (Book One: The Legend Of The Lizard Princess), 2006) Heremias (2006) was devised as the first part of a diptych (the sequel is yet to be shot) and follows the titular merchant (Ronnie Lazaro) who decides to bid farewell to the group of artisans he is a part of and go his own way. After a near-mythical journey against the forces of nature, he lands in a shady town where his ox gets stolen and goods burned. After he comes to terms with the fact that he is not going to get justice from the corrupt police department, he decides to observe the scene of crime himself, with a hope that the criminal would come back sooner or later. It is here that he learns that the local congressman’s son is going to rape and kill a girl. And it is here – almost towards the end of this nine-hour film – that there is a trace of any “drama”. Heremias, petrified, tries to convince the local police officer and the town priest to do something about it, in vain. Diaz apparently built the film on the idea of paralysis (“the metaphor of being numbed”) and it is only during this final dramatic segment, where, for the first time, Heremias shows signs of concern and empathy, that he comes out of this (sociopolitical and historical) numbness. In a way, Heremias is the Jesus figure of the story who, after a drastic spiritual awakening, realizes that there are people worst off than him and becomes willing to suffer for the sake of others (Diaz believes this quality to be quintessentially Filipino).

Heremias (2006) was devised as the first part of a diptych (the sequel is yet to be shot) and follows the titular merchant (Ronnie Lazaro) who decides to bid farewell to the group of artisans he is a part of and go his own way. After a near-mythical journey against the forces of nature, he lands in a shady town where his ox gets stolen and goods burned. After he comes to terms with the fact that he is not going to get justice from the corrupt police department, he decides to observe the scene of crime himself, with a hope that the criminal would come back sooner or later. It is here that he learns that the local congressman’s son is going to rape and kill a girl. And it is here – almost towards the end of this nine-hour film – that there is a trace of any “drama”. Heremias, petrified, tries to convince the local police officer and the town priest to do something about it, in vain. Diaz apparently built the film on the idea of paralysis (“the metaphor of being numbed”) and it is only during this final dramatic segment, where, for the first time, Heremias shows signs of concern and empathy, that he comes out of this (sociopolitical and historical) numbness. In a way, Heremias is the Jesus figure of the story who, after a drastic spiritual awakening, realizes that there are people worst off than him and becomes willing to suffer for the sake of others (Diaz believes this quality to be quintessentially Filipino).

Formally, Heremias deviates starkly from its legendary predecessor. Diaz seems to have found a new alternative to suit his long duration filmmaking style in digital video, where there is no worry of wasting film stock. He shoots in extremely long shots but mixes in close up. Diaz’s compositions early on in the film embody both fast moving objects, such as automobiles, and Heremias’ lumbering oxcart as if providing temporal reference for his kind of cinema. However, he also seems to be in a highly experimental mode, trying to arrive at an aesthetic that he might build his later films on. As a result, Heremias seems a tad derivative and falls a notch below the preceding and following films of the director. Where in later films he would fittingly cut after three or four seconds before and after a character enters or leaves the frame, here he provides a leeway of over a quarter minute, unnecessarily making the shots self-conscious (There is an hour-long fuzzy shot of Heremias watching a bunch of stoned teenagers partying, whose length, I believe, is not justified). But many of these shots are also highly rewarding and some even emotionally cathartic (for instance, the sublime shot where the light from Heremias’ lantern pierces the screen gradually). Ultimately, the film comes across as a minor, transitional (but nevertheless commendable) work that has a lot going for it thematically.

Kagadanan Sa Banwaan Ning Mga Engkanto (Death In The Land Of Encantos, 2007)

Kagadanan Sa Banwaan Ning Mga Engkanto (Death In The Land Of Encantos, 2007)

Death in the Land of Encantos (2007) was made immediately after the typhoon Reming/Durian devastated the town of Bicol (where the director had shot his previous two films), killing and displacing many families. The nine-hour film consists of two disparate threads the first of which plays out as a straightforward documentary where a filmmaker interviews the people affected by the disaster and gathers their opinion about the causes and consequences of the typhoon. The second thread in the film follows a fictional triad of artists who too live in the region of Bicol. Benjamin Agusan (Roeder Camanag) is a poet who has just returned from Russia and has discovered that his ex-lover has been buried under the outpouring of the volcano Mt. Mayon that was triggered by Reming. Then there are his friends Teodero (Perry Dizon), the level headed ex-poet who is now a fisherman, and Catalina (Angeli Bayani), a painter-sculptor who uses the debris spewed out by the volcano for her art. Benjamin is mentally disintegrating and has visions of his childhood and of his stay in Russia now and then. He is also hunted down by the government, which seems to have an agenda of killing all the soldiers and artists involved in the resistance, for his contribution to the anarchist movement. Diaz uses abstract time when dealing with sequences involving Benjamin wherein his immediate past, distant past and present (and possibly nightmares) reside in the same physical space, at times, like in The Mirror (1974) and The Corridor (1994).

Death in the Land of Encantos (2007) was made immediately after the typhoon Reming/Durian devastated the town of Bicol (where the director had shot his previous two films), killing and displacing many families. The nine-hour film consists of two disparate threads the first of which plays out as a straightforward documentary where a filmmaker interviews the people affected by the disaster and gathers their opinion about the causes and consequences of the typhoon. The second thread in the film follows a fictional triad of artists who too live in the region of Bicol. Benjamin Agusan (Roeder Camanag) is a poet who has just returned from Russia and has discovered that his ex-lover has been buried under the outpouring of the volcano Mt. Mayon that was triggered by Reming. Then there are his friends Teodero (Perry Dizon), the level headed ex-poet who is now a fisherman, and Catalina (Angeli Bayani), a painter-sculptor who uses the debris spewed out by the volcano for her art. Benjamin is mentally disintegrating and has visions of his childhood and of his stay in Russia now and then. He is also hunted down by the government, which seems to have an agenda of killing all the soldiers and artists involved in the resistance, for his contribution to the anarchist movement. Diaz uses abstract time when dealing with sequences involving Benjamin wherein his immediate past, distant past and present (and possibly nightmares) reside in the same physical space, at times, like in The Mirror (1974) and The Corridor (1994).

Like in many contemporary works from around the world, fact and fiction reside alongside in Diaz’s film, even interpenetrating each other at times. Although this does reinforce the reality that the film is based on, Diaz views the marriage as a purely ethical decision intended to avoid exploitation of his people’s miseries (He had shot the documentary part before even deciding to make the film). As a result Encantos is like a Herzog film that encompasses its making-of. A peculiar thing that one notices about the film is that it is so full of artists – painters, sculptors, poets, filmmakers and writers all over. On that basis alone, one could say that Death in the Land of Encantos is Diaz’s most personal film. The film is built largely around long conversations that invariably end up discussing the role of artists in a revolution. Through the contrast between the two sections of the film, Diaz may just be exploring the seemingly unbridgeable chasm between artists and common folk that, as Evolution had elucidated, exploitative, commercial media have occupied. However, he is also very hopeful about the work of artists. Mt. Mayon is apparently symbolic of everything Filipino – both its beauty and its ugliness. Catalina making beauty out of its ugliness is what Diaz, as a filmmaker, seems to be attempting too – to embrace the state of Philippines in its entirety and use his art to correct its blemishes and restore its glory.

Melancholia (2008) If Evolution of a Filipino Family delineated the Filipino political situation through the eyes of common folk (some of whom aid the resistance movement) and Death in the Land of Encantos revealed it through the point of view of the artists, Melancholia (2008) confronts the issue head on and presents the struggle from standpoint of the resistance fighters themselves. One gets the feeling that this is the film that Lav Diaz was working towards all along. Melancholia is divided starkly into three segments each of which takes place in different time frames. The first segment is set in the town of Sagada and simultaneously follows three seemingly unrelated characters. Rina (Malaya Cruz) is a nun who wanders the streets of the town collecting charity money for the poor, Jenine (Angeli Bayani) is a streetwalker who seems to be having some trouble doing her job and Danny (Perry Dizon) is a procurer who also surreptitiously runs live sex shows for willing customers. It is soon revealed that these personalities are only characters being played by the three as a part of a rehabilitation program initiated by Danny (actually Julian) to cope up with the loss of their kith and kin in the resistance movement. The progressively elliptical second and third segments of the film respectively show the time periods following and preceding the trio’s stint in Sagada and gradually reveal the actuality behind these masks that the three have put on.

If Evolution of a Filipino Family delineated the Filipino political situation through the eyes of common folk (some of whom aid the resistance movement) and Death in the Land of Encantos revealed it through the point of view of the artists, Melancholia (2008) confronts the issue head on and presents the struggle from standpoint of the resistance fighters themselves. One gets the feeling that this is the film that Lav Diaz was working towards all along. Melancholia is divided starkly into three segments each of which takes place in different time frames. The first segment is set in the town of Sagada and simultaneously follows three seemingly unrelated characters. Rina (Malaya Cruz) is a nun who wanders the streets of the town collecting charity money for the poor, Jenine (Angeli Bayani) is a streetwalker who seems to be having some trouble doing her job and Danny (Perry Dizon) is a procurer who also surreptitiously runs live sex shows for willing customers. It is soon revealed that these personalities are only characters being played by the three as a part of a rehabilitation program initiated by Danny (actually Julian) to cope up with the loss of their kith and kin in the resistance movement. The progressively elliptical second and third segments of the film respectively show the time periods following and preceding the trio’s stint in Sagada and gradually reveal the actuality behind these masks that the three have put on.

True to its title, Melancholia is a film that wallows in sadness. It is also probably Diaz’s most cynical work to date (although Diaz is staunchly against cynicism: “There’s hope even if we still have a very corrupt and neglectful system. We cannot allow cynicism to rule us.”). It is, in fact, the film non-linear structure that reduces the intensity of this pessimism largely. By presenting the consequences before the cause, Diaz sets up an extended, enigmatic prelude that is put into perspective only after the third part of the film plays out. It is after the film has ended that we learn that these three characters have embarked on a process of unlearning, of shedding the knowledge about bitter realities and settling down into a state of ignorant bliss, of repudiating the harshness of truth for the comforts of illusion. And it is during the very final shot of the film, when the shattered and disillusioned Julian and Alberta move away from each other and out of the now-empty frame that we feel the entire weight of the seven-and-a-half-hour film being exerted on us. Melancholia is a purgatory of sorts – a limbo between the states of resistance and defeat – whose inhabitants can feel neither the vigor of life nor the solace of death. “Many people are like Alberta” tells one of the characters early on in the film. And that is the most disheartening part.

Walang Alaala Ang Mga Paru-paro (Butterflies Have No Memories, 2009)

Walang Alaala Ang Mga Paru-paro (Butterflies Have No Memories, 2009)

The director’s cut of Butterflies Have No Memories (2009) is something of a misnomer. For one, Diaz had to shoot and cut the film so that it didn’t run for a minute more than the one-hour mark. As a result, it feels as if Diaz had one eye on his film and the other on his watch. There are shots that are abruptly drained off their life and some that feel perfunctory. But the film also seems to mark a turning point in Diaz’s outlook towards the Filipino people. Perhaps for the first time, Diaz portrays the common folk (and perhaps a particular social class) as being almost completely responsible for their misery. In Butterflies, an ex-Chief Security Officer at the mines, Mang Pedring (Dante Perez), blames the mining company, which has withdrawn production after protests by the church and activist organizations, for the economic abyss he and his friends are living in. But it is also starkly pointed out to us that, while they were getting benefited by the mining company, these folks did nothing to set up alternate ways of business and earning and, as a result, find themselves foolishly hoping for a past to return, even when such a regression is harmful it is to the collective living on the island. Mang misguidedly plans to reverse time and reinstall the factory by kidnapping the daughter of the owner of the mining company (Lois Goff), who has returned to the island after several years and who calls Mang her second-father. What Mang tries to do overrides personal memory and disregards the fact that it is he who has lived like a moth, inside a cocoon. As, in the final shot, Mang and his friends stand wearing those Morione masks (which bring in the ideas of guilt, remembrance, conscience and redemption – so key to the film), they realize that they’ve gone way too far back in time than they would have liked – right into the moral morass of Ancient Rome.

The director’s cut of Butterflies Have No Memories (2009) is something of a misnomer. For one, Diaz had to shoot and cut the film so that it didn’t run for a minute more than the one-hour mark. As a result, it feels as if Diaz had one eye on his film and the other on his watch. There are shots that are abruptly drained off their life and some that feel perfunctory. But the film also seems to mark a turning point in Diaz’s outlook towards the Filipino people. Perhaps for the first time, Diaz portrays the common folk (and perhaps a particular social class) as being almost completely responsible for their misery. In Butterflies, an ex-Chief Security Officer at the mines, Mang Pedring (Dante Perez), blames the mining company, which has withdrawn production after protests by the church and activist organizations, for the economic abyss he and his friends are living in. But it is also starkly pointed out to us that, while they were getting benefited by the mining company, these folks did nothing to set up alternate ways of business and earning and, as a result, find themselves foolishly hoping for a past to return, even when such a regression is harmful it is to the collective living on the island. Mang misguidedly plans to reverse time and reinstall the factory by kidnapping the daughter of the owner of the mining company (Lois Goff), who has returned to the island after several years and who calls Mang her second-father. What Mang tries to do overrides personal memory and disregards the fact that it is he who has lived like a moth, inside a cocoon. As, in the final shot, Mang and his friends stand wearing those Morione masks (which bring in the ideas of guilt, remembrance, conscience and redemption – so key to the film), they realize that they’ve gone way too far back in time than they would have liked – right into the moral morass of Ancient Rome.

[Death In The Land Of Encantos Trailer]

http://theseventhart.info/2010/05/16/the-films-of-lav-diaz/

Lav Diaz: As Long As It Takes.

Lav Diaz: As Long As It Takes.

Guest blog by George Clark

"I believe that the greatest struggle in life is the struggle to become a good human being."

Lav Diaz[i]

The work of Lav Diaz, more than other internationally celebrated filmmakers, is discussed more than seen. Already his filmography has a nearly legendary status due to its remarkable length. His last five films have a combined running time of over 40 hours and he shows no sign of slowing down. His breakout film Batang West Side (2002) signaled both Lav's first exploration of uncommon duration (its five hours long) as well as his break from the established film industry. Since then Lav has produced one of the most remarkable and distinct bodies of work in contemporary cinema and in turn helped to inspire and lead the way for a whole generation of filmmakers across South East Asia and particularly in his home country.

Despite popular conceptions, the duration of his work is by no means the only story; Lav is a deeply committed political and literary film maker. In responding to a question about the length of his work he recently commented that he understands that “convention tells you that a film has to be two hours, mainly for commercial purposes. But I don’t have anything to do with commerce or the marketplace, I just make my films.”[ii] The duration of his work can maybe best be understood in relation to literature, his work often employs novelistic structures, overlapping stories and complex story lines that weave together the lives and fates of many characters. Lav’s early film The Criminal of Barrio Concepcíon (1999) was inspired by Fyodor Dostoyevsky and various critics have compared his recent epics to works of Russian Literature. Lav credits his parents for this influence “my parents are bookworms and storytellers and teachers. They read and read and read. My father was very much into Russian literature.”[iii]

His work is also framed by the traumatic plight of his country whose history has seen it pass from Spanish to American colonizers in the 20th Century before its tragic independence in 1946 which was dominated by military dictatorship of Marcos, who left a continuing legacy of corruption, military brutality and suppression of democratic and human rights up to the present. Lav's work is colored by a reflection and examination of this complex history, yet defiantly seeks to highlight the stories of those outside of the countries woes, to explore the abandoned and neglected, from the rural communities to artists and failed revolutionaries. As the Fillipino critic Alexis and early champion of Lav's work stated, "The shadow cast by Ferdinand Marcos’ imposition of Martial Law stills looms prominently over the country, nearly twenty years after the dictator’s reign has ended. Marcos created a legacy; not only of fame and wealth, but of stifled hands and silenced voices; a legacy of disempowerment."[iv]

It is within this context of the disempowered that Lav's work operates. His works encompass many suppressed stories and tales, outlawed revolutionary songs sung in the night as well as fantasies and nightmares that stem from the countries rich and diverse folk culture. His films are filled with richly drawn and complex characters, and the many stories they contain are expertly structured, often combining documentary and fictional material as well as a remarkable treatment of filmic time and causality. Lav's work is unlike anything else in cinema, its marries the aesthetic of Bela Tarr with the performance and conspiratorial narratives of Jacques Rivette, the existentialism of Dostoevsky with the levity and atmosphere of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. These unique films perhaps provide their own best companions; each work is distinct and equally innovative, displaying signs of a constantly exploring artist and a conception of cinema as a live and evolving entity still far from being defined and especially not restricted to the feature length norm.

His work is celebrated by festivals around the world (such as the Venice Film Festival that awarded Melencholoy with the prestigious Orizzonti Grand Prize in 2008) but so far has had little exposure in the UK. As such the upcoming screenings at the AV Festival represent the first real opportunity to experience his work in the UK and it’s hard to think of a better place to watch them. Within the lovingly built and run auditorium of the Star and Shadow cinema, a building that in itself stands for an understanding of cinema as a communal and non-commercial experience, Lav’s work will be free to run throughout the day and their generous duration will help turn the audience into a unique community. These films are made to be watched together, to be experienced, to be lived with. The community that coheres around any work helps to define and enrich it. To watch a film by Lav is to experience an essential and unique conception of time and space, a conception born of resistance and faith in cinema as a transformative art. They are as long as an honest day’s work and much shorter than a TV box set, once they begin and you allow yourself to be taken with their unique pacing and rhythms, they’ll reward your investment with something most cinema has forgotten is within its capacity to offer.- George Clark

Time, it’s on Lav Diaz’s side. “Malay time,” he said after the Toronto screening of his nine-hour-and-five-minute Death in the Land of Encantos. “I’m a Malay as much—maybe more—than I am a Filipino. We Malays are governed more by space and nature than conventional time.” What underlies the shattering and disturbing reality of Diaz’s new work is a stunning 2006 catastrophe: nature, in the form of the profoundly devastating Super Typhoon Durian, combined with the explosive power of the Mayon volcano, wiped out physical space—the Bicol region on the central island of Luzon—along with thousands of innocents. In the face of this, and in the experience of watching Death in the Land of Encantos from beginning to end, time itself dissolves. In fact, Diaz controls the sense of time to such a degree that it no longer matters. In his hands, we all become Malay.

This is just one of the paradoxes to ponder about Diaz’s cinema, which has helped frame—though not imperiously define—the new independent Filipino cinema over the past decade. In a group of relative youngsters, Diaz is the wise elder, and his work, starting with Batang West Side (2002), gave permission to a generation to radically question the precepts of an overwhelmingly crass and commercial film culture whose past rebels, like Lino Brocka, are so rare that they’re treated like mythical heroes.

Now that Raya Martin, John Torres, and the rest have come into their own—forming the most dynamic and daring national cinema anywhere—it’s thrilling to see Diaz graze deeper into his own Malay ecosystem, where viewer adaptation to local conditions is absolutely essential, where certain categories can be tossed out with the trash. This creates some vexing, even hilarious, situations as festivals don’t quite know how to classify and exhibit the wild and roaming Lav. In Venice, The Orrizonti jury gave Encantos a special prize, but Venice programmers had slotted it in Orrizonti’s documentary category, even though Encantos is emphatically not a documentary. Toronto programmed it in a comfy, small screening room where viewers could stretch out, have a small table for food, and co-exist with the movie for most of an entire day. But Toronto’s catalogue note tried to titillate with some bizarre nonsense about “a graphic, extended lovemaking session,” while the well-intended idea to include the film in the festival’s new “Future Projections” section was a mistake. Sure, one could wander into the Spin Gallery to catch some scenes (then wander back several minutes later and think you were watching the same scene, even though you actually weren’t), but the film was plainly not served well.

The only real way to be with Diaz’s cinema is to sit in a pitch-dark room, watch, and let the outside world peel and drop away. Besides, a genuine epic is being told. In Durian’s wake, a poet named Benjamin Agustan (Roeder Camanag) returns to his home village, Padang, to see if any family members survived and if there’s anything left to salvage. Significantly, Benjamin is a leftist poet, a victim of torture by ruthless state security police, an exile who has spent several years in Russia. He returns to a place of apocalypse and ghosts, where the landscape has become downright lunar and the few trees left are awkward sticks in the ground, but also where, amazingly enough, a pair of old artist friends—sculptor Catalina (Angeli Bayani) and fellow poet Teodoro (Perry Dizon)—are trying to continue to live and work.

Benjamin has to adjust and dial down from the metropolitan, civilized but also odd and dislocating life he’s led in Russia (“Russians,” he tells Teodoro, “are a strange race—they’re Europeans, and not Europeans”) to this utterly denuded and tragic world, in which one’s sense of home has been ripped out and tossed away. Benjamin’s poetic instincts are both fueled and burdened by the memories of past lovers; an ex-lover looks very real as she’s nude, lying on her bed, but recurring images also seem to make her into a spectre, while a strange nighttime Zagreb setting is the basis for thoughts of another lost love. (Here, Diaz does something that Torres specializes in, salvaging footage from another film—in this case, an unfinished short about Filipino ghouls adrift in Eastern Europe—using it for other purposes and altering its context.) Benjamin’s memories grow especially intense concerning his family, including a mother who had long ago gone insane.

As he had developed over the course of making Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004) and Heremias (2006), Diaz establishes concrete reality and facts alongside a nearly mystical state of mind that at first occupies and eventually permeates the work. This shift precisely tracks the filmmaking process. Encantos did indeed begin as non-fiction; the former reporter Diaz dashed to Bicol (where he made his previous two films) two weeks after Durian hit to record the environmental and human conditions. Clearly, although he hasn’t said such, he discovered an extraordinary stage expressing a cosmic tragedy that called for some kind of narrative. The typhoon’s actual victims speak to Diaz’s camera, but the fictitious characters inside Encantos speak and walk inside a patiently conceived deep focus mise en scène, like somnambulistic beings out of I Walked with a Zombie (1943). They have enough time and space to ponder many things: the existence of a deity, the state of their country, the alchemy between nature and art (Catalina explains that she makes her sculptures from Mayon’s lava, as a way of taming it), how mortal beings become ghosts (Catalina to Benjamin: “You’re like a ghost—you go away, and then you reappear”).

There are many examples of how Diaz manages this interpolation of the concrete and ineffable, but one in particular stands out so impressively that it becomes a signature effect. His fixed DV camera, shooting in wide angle to better encompass a massive landscape, runs for minutes, sometimes even over ten, until something happens: a figure in the far distance appears. When does it appear? I’ve watched this phenomenon since Evolution, and despite intense concentration, I can never spot the exact moment when the character materializes on screen. It’s a cinema viewing experience without parallel, exactly recreating what happens if one were to stand in a large landscape and wait for a person to arrive from the extreme distance.

Several scenes have Benjamin suddenly emerging within such a space, reinforcing Catalina’s remark. By the seventh and eighth hours of Encantos, Benjamin is trapped between this reality and Bicol’s shadow world. Camanag stumbles around in a near-dead stupour, buffeted by the loss of his family, his failed attempts to make sense of his mother’s madness, and his inability to stoke some sort of love with Catalina, collapses in a heap as if the air’s been sucked out of him. Art has the last word: Catalina recites a vivid, stark chunk of Benjamin’s verse (written by Diaz, proving that he’s a poet of the first degree) that brings him back to life. Even a closing flashback of Benjamin being tortured doesn’t detract from the poem’s efficacy.

With such declarative expressions of art, Diaz is encouraging the viewer to free-associate with a basket teeming with cultural—mostly Western—associations. It’s impossible to consider his awed shots of the perfectly conical and gorgeously intimidating Mayon, in combination with Benjamin’s gradual dissolution, and not think of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. Just as it is to gaze upon the impossibly rocky landscapes over stretches of extended time and not recall L’avventura (1960). Then there’s Rilke, whose apt quote, “Beauty is the beginning of terror,” opens Encantos. Images of Pudovkin and Tarkovsky tumble into the mind when Benjamin and Teodoro discuss Russia. And then there are the two great poles of theatre history, that are here elegantly folded into each other: Aeschylus’ voice of personal and national tragedy in the form of lament and pure grief, and Beckett’s existential comedy, the endless wait for the thing that will never transpire. But the wait, the wait…the bliss in that wait, the physical stamp—exhaustion, giddiness, discomfort—felt by watching that wait is the special, new thing that Lav Diaz has brought.

Spotlight | Death in the Land of Encantos (Lav Diaz, The Philippines)

Time, it’s on Lav Diaz’s side. “Malay time,” he said after the Toronto screening of his nine-hour-and-five-minute Death in the Land of Encantos. “I’m a Malay as much—maybe more—than I am a Filipino. We Malays are governed more by space and nature than conventional time.” What underlies the shattering and disturbing reality of Diaz’s new work is a stunning 2006 catastrophe: nature, in the form of the profoundly devastating Super Typhoon Durian, combined with the explosive power of the Mayon volcano, wiped out physical space—the Bicol region on the central island of Luzon—along with thousands of innocents. In the face of this, and in the experience of watching Death in the Land of Encantos from beginning to end, time itself dissolves. In fact, Diaz controls the sense of time to such a degree that it no longer matters. In his hands, we all become Malay.

This is just one of the paradoxes to ponder about Diaz’s cinema, which has helped frame—though not imperiously define—the new independent Filipino cinema over the past decade. In a group of relative youngsters, Diaz is the wise elder, and his work, starting with Batang West Side (2002), gave permission to a generation to radically question the precepts of an overwhelmingly crass and commercial film culture whose past rebels, like Lino Brocka, are so rare that they’re treated like mythical heroes.

Now that Raya Martin, John Torres, and the rest have come into their own—forming the most dynamic and daring national cinema anywhere—it’s thrilling to see Diaz graze deeper into his own Malay ecosystem, where viewer adaptation to local conditions is absolutely essential, where certain categories can be tossed out with the trash. This creates some vexing, even hilarious, situations as festivals don’t quite know how to classify and exhibit the wild and roaming Lav. In Venice, The Orrizonti jury gave Encantos a special prize, but Venice programmers had slotted it in Orrizonti’s documentary category, even though Encantos is emphatically not a documentary. Toronto programmed it in a comfy, small screening room where viewers could stretch out, have a small table for food, and co-exist with the movie for most of an entire day. But Toronto’s catalogue note tried to titillate with some bizarre nonsense about “a graphic, extended lovemaking session,” while the well-intended idea to include the film in the festival’s new “Future Projections” section was a mistake. Sure, one could wander into the Spin Gallery to catch some scenes (then wander back several minutes later and think you were watching the same scene, even though you actually weren’t), but the film was plainly not served well.

The only real way to be with Diaz’s cinema is to sit in a pitch-dark room, watch, and let the outside world peel and drop away. Besides, a genuine epic is being told. In Durian’s wake, a poet named Benjamin Agustan (Roeder Camanag) returns to his home village, Padang, to see if any family members survived and if there’s anything left to salvage. Significantly, Benjamin is a leftist poet, a victim of torture by ruthless state security police, an exile who has spent several years in Russia. He returns to a place of apocalypse and ghosts, where the landscape has become downright lunar and the few trees left are awkward sticks in the ground, but also where, amazingly enough, a pair of old artist friends—sculptor Catalina (Angeli Bayani) and fellow poet Teodoro (Perry Dizon)—are trying to continue to live and work.

Benjamin has to adjust and dial down from the metropolitan, civilized but also odd and dislocating life he’s led in Russia (“Russians,” he tells Teodoro, “are a strange race—they’re Europeans, and not Europeans”) to this utterly denuded and tragic world, in which one’s sense of home has been ripped out and tossed away. Benjamin’s poetic instincts are both fueled and burdened by the memories of past lovers; an ex-lover looks very real as she’s nude, lying on her bed, but recurring images also seem to make her into a spectre, while a strange nighttime Zagreb setting is the basis for thoughts of another lost love. (Here, Diaz does something that Torres specializes in, salvaging footage from another film—in this case, an unfinished short about Filipino ghouls adrift in Eastern Europe—using it for other purposes and altering its context.) Benjamin’s memories grow especially intense concerning his family, including a mother who had long ago gone insane.

As he had developed over the course of making Evolution of a Filipino Family (2004) and Heremias (2006), Diaz establishes concrete reality and facts alongside a nearly mystical state of mind that at first occupies and eventually permeates the work. This shift precisely tracks the filmmaking process. Encantos did indeed begin as non-fiction; the former reporter Diaz dashed to Bicol (where he made his previous two films) two weeks after Durian hit to record the environmental and human conditions. Clearly, although he hasn’t said such, he discovered an extraordinary stage expressing a cosmic tragedy that called for some kind of narrative. The typhoon’s actual victims speak to Diaz’s camera, but the fictitious characters inside Encantos speak and walk inside a patiently conceived deep focus mise en scène, like somnambulistic beings out of I Walked with a Zombie (1943). They have enough time and space to ponder many things: the existence of a deity, the state of their country, the alchemy between nature and art (Catalina explains that she makes her sculptures from Mayon’s lava, as a way of taming it), how mortal beings become ghosts (Catalina to Benjamin: “You’re like a ghost—you go away, and then you reappear”).

There are many examples of how Diaz manages this interpolation of the concrete and ineffable, but one in particular stands out so impressively that it becomes a signature effect. His fixed DV camera, shooting in wide angle to better encompass a massive landscape, runs for minutes, sometimes even over ten, until something happens: a figure in the far distance appears. When does it appear? I’ve watched this phenomenon since Evolution, and despite intense concentration, I can never spot the exact moment when the character materializes on screen. It’s a cinema viewing experience without parallel, exactly recreating what happens if one were to stand in a large landscape and wait for a person to arrive from the extreme distance.

Several scenes have Benjamin suddenly emerging within such a space, reinforcing Catalina’s remark. By the seventh and eighth hours of Encantos, Benjamin is trapped between this reality and Bicol’s shadow world. Camanag stumbles around in a near-dead stupour, buffeted by the loss of his family, his failed attempts to make sense of his mother’s madness, and his inability to stoke some sort of love with Catalina, collapses in a heap as if the air’s been sucked out of him. Art has the last word: Catalina recites a vivid, stark chunk of Benjamin’s verse (written by Diaz, proving that he’s a poet of the first degree) that brings him back to life. Even a closing flashback of Benjamin being tortured doesn’t detract from the poem’s efficacy.

With such declarative expressions of art, Diaz is encouraging the viewer to free-associate with a basket teeming with cultural—mostly Western—associations. It’s impossible to consider his awed shots of the perfectly conical and gorgeously intimidating Mayon, in combination with Benjamin’s gradual dissolution, and not think of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. Just as it is to gaze upon the impossibly rocky landscapes over stretches of extended time and not recall L’avventura (1960). Then there’s Rilke, whose apt quote, “Beauty is the beginning of terror,” opens Encantos. Images of Pudovkin and Tarkovsky tumble into the mind when Benjamin and Teodoro discuss Russia. And then there are the two great poles of theatre history, that are here elegantly folded into each other: Aeschylus’ voice of personal and national tragedy in the form of lament and pure grief, and Beckett’s existential comedy, the endless wait for the thing that will never transpire. But the wait, the wait…the bliss in that wait, the physical stamp—exhaustion, giddiness, discomfort—felt by watching that wait is the special, new thing that Lav Diaz has brought.

Beware of the Jollibee: A Correspondence with Lav Diaz

By Andréa Picard

Twenty years ago, when under the rule of a sole dictator, we knew well whose wrists deserved to feel the sharp ends of our knives. Today, in a society so quick to judge and pass blame, the only flesh that remains to be examined is our own. Diaz’s camera, steadfast, unwavering, reveals the truths only found beneath the surface, and points us on the path to deliverance.—Alexis Tioseco, 2006

In mid-April, Lav Diaz came to Toronto to attend the Images Festival with his most recent film, the six-hour Florentina Hubaldo, CTE. A work of profound emotional depth and stunning deep-focus chiaroscuro cinematography, it lingers in the imagination for an unusually long time; so complete and devastating is its wounded, weary, and wretched world. Its tale of a young, beautiful woman who lost her mother at an early age (“in unexplained circumstances”), is shackled to a rickety bed by her perpetually drunk, exploitative father, and is continuously raped by men as her battered grandfather is forced to witness her suffering, can hardly get more bleak. And yet, its sustained descent into a Tarr-like miserabilism is revealed as complex, multi-faceted, and paradoxical at every sodden turn, intersecting with a few other storylines and a tireless, unseen gecko providing some impressive diegetic sound from the natural world.

The film takes place in Bicol near the alluring but ominous volcano, which erupted as recently as 2008, decimating the region, its molten lava swallowing upwards of 3,000 lives. Still, people returned to live there, despite the fatal risk, as if a supernatural magnetism drew them back. But, as the film amply and relentlessly (at times, punishingly) demonstrates, home is not synonymous with safety and comfort; in Bicol, for Florentina Hubaldo, it’s a literal hell on earth.

She, of course, is the Philippines—a country that has endured war, colonial rule, civil strife, abject poverty, and merciless environmental disasters. (The independent filmmaking community in Manila has, significantly, also been tarred by tragedy. The violent loss in 2009 of film critic, educator, producer, and all-around mobilizer Alexis Tioseco—to whom Diaz’s A Century of Birthing [2011] is dedicated—is still being felt.) While devastating earthquakes and tsunamis in the Philippines have become all-too-common headlines, the punishing rainy season now extends from June to December, in great part due to global warming. With flooding rains and whipping winds, a plundering Mother Nature destroys homes, village infrastructures, and sweeps away lives and possessions in a perpetual cycle of destruction and obligatory renewal. These forceful downpours are recurring characters in recent Filipino cinema, from the dirty deluge in Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (2007), or the ominous omens in his controversial and unfairly maligned Kinatay (2009), to the dreamy rainfall in Raya Martin’s elegant and gorgeously stylized period piece, Independencia.

The rain, plaintive and plentiful, and Alexis’ generous spirit and truncated aspirations for a burgeoning Filipino cinema replete with a solid awareness of history and healthy discourse, were both wistfully discussed during a lazy, sunny day spent with Diaz, who is impassioned about culture and its global crisis. Like the CTE in the title (“Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy,” a progressive degenerative brain disease caused by repetitive blows to the head), Diaz frequently refers to the state of regression attending the majority of the cultural affairs in the Philippines. In no ways endemic to his own country, the crisis in culture (remarkably contradictory, from the rise of corporate marketing to the bulimia of curatorial studies departments and the logorrhea of their posturing, to the hegemony of jargon-laced criticism and its crutches, the shuttling to and from elitism to mass-media, the increasingly bloated museum admission fees, the prevalence of blockbuster shows, etc…) weighs heavily upon him as an uncompromising artist with fewer and fewer funding options, and an audience base that is loyal, but oh so small.

Invoking something (completely amorphous) along the lines of Glauber Rocha’s infamous “aesthetic of hunger,” Diaz returns to the notion of a petrified perception of art, both at home and abroad. That serious should be so readily mocked (Susan Sontag lamented this long ago and the disdain and intolerance have seemingly only grown) is no longer surprising or jarring given today’s cultural and economic climates, and yet, there is a sense of the irrevocable: what Diaz has dubbed “the Jollibee” phenomenon. Essentially the McDonald’s of the Philippines, Jollibee is a ubiquitous, enterprising chain of fast-food restaurants that has colonized youth culture and mass consumption. “A Triumph for and of the Filipino,” proudly declares its website, as the literally eye-popping mascot casts his spooky spell upon the nation. Today’s youth feed on “yumburgers” as they zealously pose for keepsake photographs with the frighteningly neon-coloured “Jollibee” and the gap continues to widen…

On the ubiquity of storms in recent Filipino cinema:

Lav Diaz: Resilience. We are the storm people. The storm could be the Filipino’s original Anito (God); we had so many gods before Christ and Allah came to our endless shores. On the average, the Philippines is battered by 28 storms every year, but that doesn’t make us a storm-battered race. In fact, we’ve become this storm-loving people. The storm is very much a part of our reality. Double that average, the Filipino can still take it. I wouldn’t call it a sado-masochistic psyche, but more of a resigned acceptance because you can’t do anything about it; it’s nature’s way. And you go back to the pre-Islamic and pre-Catholic Filipino Malay perspective—life is governed by nature. So, yes, the storm gives the Filipino a resiliency that’s uniquely Filipino because it’s become a metaphor for restarting, rebuilding, reconstruction, relocation, rebirth, recalling, renaming, resurfacing, reissuing, recurrence, reluctance, relapse, return, retain, remain, regain, resurrect, remiss, relief, rogue, rotten, rampant, relax, renegade, rob, run, rush, rip, ripe, rum, rug, rat, rut, retrogression, retro, rope, and rock ‘n’ roll. Amid a very corporeal history, there’s the storm, the Filipino’s god of all gods, which has somehow become the great paradoxical equalizer, giving the Filipino a complex logic/illogic cultural discourse, a philosophy founded on the patterns of nature; the meaning of existence is appropriated by nature’s ways. It’s so normal to drown in a flood, be buried by a landslide, to be sliced by debris from a billboard, and be twisted by 21 years of Marcos’ brutality. Hey, there’s a storm. I wrote this piece during the shoot of Death in the Land of Encantos (2007, part of the Benjamin Agusan poems, but I excluded the ones I wrote in English):

I shall sit on chairs clasped by dirty wind

I shall stare on empty skies and mud, and crushed houses

The smell of decay cripples all aromas of caffeine and grass

The trees are quiet now, devoured by the mightiest rains

The earth is sepia now, brown and black, even before dust

The street is still once more, blood had dried on concrete and waste

Worms roam the land, impregnable with their desires for rotten flesh

Worms are angels who eat the ones they could not save

What I have are pieces of sorrow, pieces of pain left by December,

And September.

What I have are days always undone

By absence—

Your perpetual absence.

On the impossibility of submitting a list of Top 10 films of all time to Sight and Sound…

Diaz: This is the most abused exercise in cinema. Top 10 films, or, The Greatest 100 Films of All Time, or, 1000 Essential Films. And why do we do it still, ad infinitum, ad nauseum? Honestly, it just feeds the ego of the ones who do it, and, of course, of the ones mentioned. They will actually kill or die for it. It boggles the mind. But then it’s a valid exercise. And I respect people who do it, no matter how idiotic their choices/discourses sometimes are. I’ll even defend them. Yes, the canon, like it or not, is a necessary evil. Canon-making built so many sects and churches of cinema. Godard ran away from it, scared shitless upon realizing that Narcissus is staring at him in his favourite mirror, himself. But then he’s a god who created cinema, so he can’t destroy it, and we dread the day when he will finally leave cinema because he is infinitely a part of the Top 10 and The Greatest 100 Films of All Time and the 1000 Essential Films. In North Korea, the cinemaniac and late megalomaniac Kim Jong-il actually imposed a canon, all films starring himself, waving, smiling, visiting troops and factories, kissing babies, hugging the blind, praising uranium in thickly clogged shoes and propagating hairmania. And we know what happened and what is still happening in sad, sad North Korea. The wisdom and analogy is never, ever trust the canon. Keep an open mind but always keep Kim in mind. By keeping an open mind, we understand that the canon is part of the greater discourse of cinema; that’s short of saying that it’s still relevant. And I don’t think it’s elitist. Greater discourse always begs the proverbial question: “Do we really know the real Socrates?” or, putting it in a direct way: “Do we really know cinema?”

I’m throwing back these questions to you, Andréa: “Is the canon a necessary evil? No longer relevant? Elitist?”

Andréa Picard: I’m guilty of indulging in this exercise and can certainly acknowledge that part of the impetus for this endless list-making inevitably comes from ego, but also, and most importantly, it derives from passion, desire, and a sense of responsibility. I agonized over my list, which was inevitably followed by a period of anxiety and regret. I still feel like I was unwise in my choices. But those sentiments have nothing to do with the fear of being judged or having anything at stake (subconsciously having little faith in the exercise, I guess) and stem instead from a relentless internal debate. The slippery adjective “best” does not help matters. Can personal epiphanies be measured against historical importance and great leaps in evolution? Don’t we all dodge the question of sensibility as it relates to our own discipline? Visconti’s Ludwig (1972) is an astonishing work of cinema. Could I honestly call it one of the Top 10 films of all times? I once did, but can no longer comfortably make this claim. One wants to upset the canon because it’s a barometer of normalcy, of quiet, comfortable “quality.”

And as you have rightly pointed out, there are countless films that will never be known to us, that have disappeared over time, during times of war, environmental catastrophe, or due to lack of preservation, or never emerged at all. The canon is inherently fallible, as we are. And should be ever-changing, as we change and the world changes. Re-evaluation can be an important exercise, but even more important is the need and curiosity to look beyond establishment, beyond what is accepted, praised, welcomed, studied, supported. Because of the nature of my work, I think a lot about what the term avant-garde means today. It’s not something that I can confidently or categorically answer.

Making a list is one thing, but taking risks in programming by promoting work that doesn’t appeal to the masses, that challenges our notions of art, that puts forth an unique vision, that questions film form, that takes a stance politically, that derails orthodoxy, is so much more critical today. Especially in light of how culture has become corporate commodity. Legacies are generated through lists and logs, but also through collective memory, and hopefully, enlightenment. Is that too naïve and old-fashioned? And let’s not forget that some of the films commonly referred to as canonic were derided and misunderstood in their time, too.

Why continuously mine the history of the Philippines in your filmmaking?

Diaz: I’m a part of this culture and every time I work on a concept, idea, or an inspiration, the struggle of my country, my people, somehow always comes out. Culture works that way. The subconscious has a way of dictating perspectives; once the creative process starts, the introspective being in you will mysteriously pull some reservoir of materials that’s been there, the one that you call history, or maybe suppressed stories and desires, not just personal but also collective; it encompasses the entire struggle of humanity. It’s not always a deliberate act. Man is a psychoanalytic being. The greatest artists on earth possess a repository of history and visions in their subconscious, sublime and transcendent, quite different from the very fragile and oftentimes biased and prejudicial oral and written histories. It’s just there. For lack of explanation, some call it madness or genius. Freud and Jung debated this, and realized that psychiatry has no concrete answer to humanity’s frailties. They ended up where they started: “Why?” And so, we continue to mine/examine/confront the histories of our cultures. Once, a friend made the mistake of giving the script of one of my still-unfinished works about a very important person during the Philippine Revolution against Spain and America to a history professor. He emailed me a lengthy attack telling me I got it all wrong. Who owns history?

Who are the filmmakers, artists, writers, or musicians who inspire you?

Diaz: Weeks ago, I went hiking with a friend in a mountainous town in the Philippines. We came upon a spider and his delicately made web house. We were stunned, speechless, in absolute awe. We sat there, almost in tears. What a great piece of work. The spider is even smaller than 1/8 of an inch, and beside a windswept highway, in the middle of two small trees, he built a formidable work. My friend and I made some geometrical analysis about it. We concluded, “Impossible, impossible!” Logic will tell you that, yes, a spider creates a web house. Simple. This spider created a masterpiece. Just embrace the mystery of aesthetics, beauty. And so we declared him the greatest artist of this century.

What place does art have in society today?

Diaz: Art remains marginalized in terms of accessibility; the so-called reach to a broader mass on issues of critical and practical applications, yet it remains the most relevant aspect of humanity’s cultural struggle. The only exception of course is rock music, whose reach is extremely phenomenal. Of course, commercial movies have the same reach. Rock music has achieved an utterly unique stature in that even the most aesthetically demanding works can easily captivate millions of people. That can’t be said with serious cinema. Art cannot escape the issue of gravitas, the issue of contradiction, and yes, elitism. A Cezanne that fetches millions can’t move a rice farmer in Thailand whose understanding of aesthetics is confined to a beautiful sunrise, the dinner prepared by his wife, the rain, the catfish, and a good harvest. The modern dancer in Berlin can always claim she is revolutionizing movement but the criminal Bashir al-Assad will continue to aim his guns and rockets at his own people. When the UN and the civilized world cannot liberate the Syrian people, what can art do? Art feeds and liberates the soul, yes, but the modern age has become the age of urgency. The zeitgeist tells us that we need to save the world now—from fundamentalism, from ignorance, from apathy.

In the face of the relentless barbarism in this supposedly very modern age, art becomes a stand, a political tool, an ideological line to maintain man’s sanity, or even to save humanity from an eventual retrogression and annihilation. Non-condescendingly speaking for myself, my faith in art remains the same. I am very stubborn with my aesthetic because I believe that the artist can still contribute to greater culture.

What role should film criticism play?