Akademski obrazovan muzičar koji u svemu što radi ide uz dlaku i zanima se za rubne pojave i autore. Primjerice, prevodi poeziju s jezika koje ne poznaje. Objekti za njega nisu instrumenti podređeni autoru, nego suradnici, aktori koji te mogu odvesti nekamo gdje nisi bio.

www.inbetweennoise.com/

Sound Propositions 04: Steve Roden (part I)

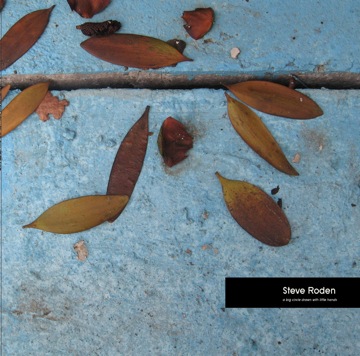

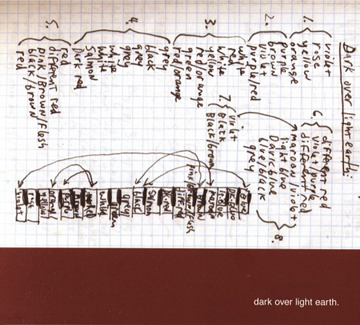

a big circle drawn with little hands was created from a box of things sent to me by sylvian, who runs the ini itu label. the box contained everything from newspapers, coins, wooden toys, pamphlets, plastic objects, plastic bags, broken airline headphones, notes, a bottle opener, a noise maker of wood, a small electronic toy shaped like a butterfly that offered tones and animal noises, cardboard, a fan, and other things. i also used a banjo in the first track, and my voice in the last track.

the lp was mastered by taylor deupree, and the cover design and photos were done by sylvain.

a number of people have attempted to “de-code” the song titles, but like the rest of the approach to the soundmaking, etc. the titles actually also came from one of the items in the box of stuff sylvain sent to me – a newspaper, and i used each of the photographs to determine the titles, based on the number of hands appearing in an image as well as the image’s narrative. the title of the lp was based on a drawing made by sylvain’s daughter.

I met Steve earlier this year at a workshop and public conversation when he performed as part of the Suoni per il Popolo festival in Montreal, and I find its best to let him do the talking as much as possible. This is the first of a two part interview conducted between June and December of 2012. As it is already considerably longer than even my already-lengthy pieces, I’ll try to keep the introductory comments to a minimum, so we can get back to his words.

Steve Roden is an artist living in Pasadena, presenting his work since the mid-’80s. The text above describes one of his most recent recordings, but the spirit conveyed by those words animates all his endeavors. In contrast to a sort of radical openness suggested in each piece, Roden adopts a series of self-imposed rules or creates idosyncratic notation to act as a guide in which to execute create decisions. A true bricoleur, this at times entails limiting the tools or resources at his disposal, often with no regard for “fidelity” or technical processes. Instead he embraces these qualities, not as flaws but as interesting in themselves. In addition to making music, he also works in many different media, including painting, drawing, sculpture, film/video, sound installation, and performance. Throughout the ‘90s he released several records under the moniker In Be Tween Noise and coined the term “lowercase” for a music that “bears a certain sense of quiet and humility; it does not demand attention, it must be discovered. the work might imply one thing on the surface but contain other things beneath. … it’s the opposite of capital letters—loud things which draw attention to themselves.” His 2001 release Forms of Paper brought attention to the term lowercase, which at the time united a wide variety of practitioners exploring silence and quiet, from lap top musicians, to electroacoustic artists to free jazz. As is the way with such things, the term took on a life of its own, though Steve still insists upon an openness in its interpretation. You can read more about Steve’s thoughts on lowercase and the history of that release at “on lowercase affinities and forms of paper.”) He has collaborated with Brandon LaBelle, Franscisco López, Jason Kahn, Machinefabriek, Stephen Vitiello, Bernhard Günter and many others

Roden’s philosophy is very much in line with that of Sound Propositions, and A closer listen as a whole. We each, as listeners, must play a central role in shaping what we hear, bringing a sort of Zen-like acceptance while still attending to Rilke’s “inconsiderable things,” a reference Roden often mentions. I can’t help but hear echoes of Nietzsche,one of Rilke’s great influences, in Roden’s approach to listening, and his conception of the artist more broadly. Nietzsche didn’t write for everyone, and certainly not for those who would cherry-pick his words. He decried the equivalent of iTunes on shuffle, music as background noise. No, Nietzsche wrote for those who would put in the effort, who could read slowly, carefully, and deeply. Roden is a similar kind of artist, that is he who has no contemporary. This can be a dangerous place to be, but for those who press on through this isolation, their work transcends the ebbs and flows of fashion. Still, as the poet Hölderlin wrote, “where danger threatens/That which saves from it also grows.” There is something creative and productive that comes from this place of risk. Not hostile or coercive, not elitist or condescending, but rather quietly carrying on its own logic, rewarding patient and careful engagement.

Steve is a rare kind of artist. One who has created a rich and diverse body of work that is uniquely his own, one who can work across media without losing his conceptual rigor, who can create resonate work and speak articulately about it, while speaking simply and without sacrificing nuance, and all the while still remaining utterly humble and approachable. His work is patient and characterized by a level of restraint that is hard to match. Rather than be confined he turns the limitations around him into that which generates the work.

Enjoy. (Joseph Sannicandro)

A playlist of the pieces mentioned in this article can be found here.

Joseph Sannicandro: I’ve heard you mention your early interest in the LA punk scene in several interviews. In my experience, many of us who are experimental music, electro-acoustic music or music that in some way draws inspiration from the avant-garde or conceptual art, have a similar background of being interested in more extreme music (punk/hardcore, or industrial music). This genealogy seems relevant to me, as opposed to those who come from the EDM/club background, or who are more formally trained in the classical tradition. Can you maybe expand on this, how the ethic of the punk scene may have influenced your aesthetic, your attitude towards promoting concerts, releasing music, and your evolving material practice itself?

Steve Roden: I can’t really emphasize how lucky I was to be able to be part of that scene from 1979-82, especially as a 15 year old. A friend and I literally encountered the scene by accident… we rode our bicycles to the Whisky A Go-Go to see a Jimi Hendrix impersonator, and the show was so great… the guy came out in a coffin and it was like Hendrix was reincarnated! We had such a good time that we went back a few weeks later expecting another rock show only to be confronted by The Screamers!!! At that time, I had hair down to my shoulders and I was wearing a Hendrix t-shirt, but nobody gave us crap, in fact most of the people, who were older than us, were super cool. I had no idea what was going on, but I remember standing there with all this crazy energy on stage and after the show I went home and cut my hair, and painted a big red no left turn sign over Hendrix’s face on that t-shirt. The next day I wore the shirt to school and a few guys picked a fight with me because of the shirt, and I felt excited and different.

“122 hours of fear”

Haha, wow, love this story and the imagery!

Yeah, I wish I remembered the Hendrix impersonator show a bit more detail… it probably was very close to Spinal Tap territory!

While the punk scene became very violent by 1982, those earlier years were fantastic, and a lot of people were very positive… we really thought we’d change the world. Yes, of course the music was very important, but even more so was the feeling of potential that came out of being part of a community. Certainly, there were a lot of drugs, a lot of angry people, and sometimes violence, but it’s clear now that for so many people who were part of that scene it fueled a very creative approach to life – as well as a strong sense of integrity: “no compromise”, etc. I have no musical training and I think half our band knew how to play their instruments and half could not. I was the singer and wrote most of the words – ridiculous songs like “kill reagan” and “jesus needs a haircut”. We were young and angry towards the government and religion, and society’s rules in general. Like every subculture, we were dreamers as well as fighters. But what was most important was that we didn’t want to be rich and famous. That was NEVER a goal. And that gave the whole thing a level of integrity that I have tried to carry forward in life… to do things the way that you want to, to find meaning in your own way, and not only to have integrity but to protect it. I don’t think I ever really felt the music or the scene was truly “extreme”, certainly not in terms of hearing someone likeMerzbow or Aube live. But the scene had a crazy wonderful energy certainly. In Los Angeles, not all of the bands offered an extreme experience - although certainly early Black Flag, Fear and the Germs did – but if you think about the variety of influences upon bands like X, Gun Club, Fear, Black Flag, the Weirdoes, the Germs, each of these bands had their own sound and their own influences, so I would not really categorize them all as extreme in sound. Punk was loud, but only in certain cases was it truly extreme – such as live Dead Kennedy’s!

Yes, these are all social scenes that I think have strong underpinnings, punk with integrity, hardcore with unity, club culture with a kind of hedonism.

This morning I was reading the newspaper and there was an article about Snoop Dog and how he re-tooled one of his songs “drop it like it’s hot”, to fit a commercial for “Hot Pockets,” which is some kind of sandwich. While I don’t begrudge anyone seeking a paycheck, it’s hard not to see that decision and not think about him as a sell-out or a compromise (for if nothing else, he is surely compromising the integrity of the original song by retooling it for an ad). I’d like to think the Clash would have been aghast at the idea of turning “white riot” into a jingle for soda pop… “rite diet, rite diet, rite diet, a flavor of its own”

Can you imagine? That’d be some soda! But still, even though Snoop obviously doesn’t need a paycheck, and not that “drop it like it’s hot” had much integrity to begin with, there is still something about making such a change that just doesn’t sit right. I like how you deploy INTEGRITY here, it’s not just an abstraction but the literal integrity of the song itself, as such.

Last year I was watching a press conference with a baseball player from this area, and instead of testing the free agent market he re-signed with the team he’d been with for several years. His decision was rooted in his relationship with his teammates, living in Los Angeles and his family. In making the decision he left a few million dollars on the table, and on the radio, some fans criticized him for not trying to get the most money he could get… but after being asked the same question by a reporter he simply said, “how much money does a person need”, and it was kind of great to see a wealthy professional athlete take less money because there were other things in life that meant more to him… so I see this dude as having a hell of a lot more integrity than Snoop Dog!

When we met back in June at the Suoni per il Popolo festival in Montreal, during a public conversation you had with Doug Moffat, you mentioned an album whose liner notes influenced you far more than the music itself, which was just speculative for so many years, until you found a copy and finally were disappointed a bit by the actual music, or at least it didn’t live up to the limitlessness of your imagination. I’m blanking on the LP at the moment, but maybe it was German? Anyway, this reminded me of something the writer Samuel R. Delany has said, in an interview with theParis Review. Excuse the long quote…

When we met back in June at the Suoni per il Popolo festival in Montreal, during a public conversation you had with Doug Moffat, you mentioned an album whose liner notes influenced you far more than the music itself, which was just speculative for so many years, until you found a copy and finally were disappointed a bit by the actual music, or at least it didn’t live up to the limitlessness of your imagination. I’m blanking on the LP at the moment, but maybe it was German? Anyway, this reminded me of something the writer Samuel R. Delany has said, in an interview with theParis Review. Excuse the long quote…

INTERVIEWER

You have suggested that the writers who influence us “are not usually the ones we read thoroughly and confront with our complete attention, but rather the ill- and partially read writers we start on, often in troubled awe, only to close the book after pages or chapters, when our own imagination works up beyond the point where we can continue to submit our fancies to theirs.” What were some of your “ill-read” books?

DELANY

Any book you have to work yourself up to read. …When such books influence you, if that’s the proper word for what I’m describing, it’s what you imagine they do that they don’t do that you yourself then try to effect in your own work, that, to me, is what’s important. What these books actually accomplish is very important, of course! But the whole set of things they might have accomplished expands your own palette of aesthetic possibilities in the ways that, should you undertake them, will be your offering on the altar of originality.

Before I read Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Conqueror books and stories, I really thought they would be the Nevèrÿon tales, or at least something like them. But I discovered that, rich and colorful as they were, they weren’t. So I had to write them myself.

I wonder if you were maybe getting at a similar concept of the ill-heard album. Or really any work of art that can be more inspiring as a specter than as a proper engagement. This sort of thing probably occurs less now that the internet has made it much easier to find out about things. The mystique fades a bit, but that’s another question.

Yeah, that is great!!! I can’t tell you how many things I love were discovered through a bad review… and with the record, being unable to hear it (this was pre-internet), it just started growing inside of me, and the [liner] notes really offered me a path to start to make my own music. The LP was by the painter Jean Dubuffet [found of Art Brut], along with the Cobra [and Situationist] artist Asger Jorn, and they borrowed a bunch of Asian and exotic instruments and made all these reel-to-reel tapes. It’s really like noise music or free jazz without the jazz parts, but Dubuffet approached music in the same way he dealt with art brut, and the liner notes are so beautiful in terms of how he speaks of playing instruments without technique – and at the time I was working with instruments, making crude instruments, and working with them to make music and I was so affected by Dubuffet’s notes that it pushed me. When I heard the actual LP, maybe 10 years ago, it sounded so completely different than I’d heard in my mind and it never would’ve inspired me in the same way. It was lucky that I had no access to the content!!!

What are some of your early memories or impressions of sound? When did you realize you were interested in sound (as such)?

This is a question I get a lot and I never know how to answer it. Honestly, as a child I don’t remember being specifically attracted to sound as sound. Certainly there were experiences that I remember strongly, such as my first tape recorder which was given to me by my father when I was 10 years old. But I did not go out and make field recordings, in fact, I distinctly remember a friend and I sitting on the tape deck’s microphone and farting and giggling a lot (a story I have never offered in an interview before!)… but most of the actual sounds I remember were not natural sounds, like the ice cream truck songs, the sound of my father’s car, and my grandfather’s whistle. Honestly, I don’t really think sound was something I responded to at a young age, certainly I have no listening epiphanies that I can remember…

I would say that I really noticed sound – as sound – when I was 12 or so. I didn’t know it at the time, but in the mid-1970’s I used to hang out at the local Tower Records store with a few friends on Saturday nights. The store stayed open until midnight, and we became friends with some of the folks who worked there, and one night someone mentioned it was my birthday and one of the clerks handed me a copy of Eno’s Another Green World as a gift. At that time I was listening mostly to Hendrix – as his was the first music I was obsessed with, buying bootlegs, etc. so I had no context for Eno at all, especially the instrumental tracks… but I remember clearly listening to one of the ambient-ish tracks “the big ship” a million times. It wasn’t that I had any interest in that kind of music, but I loved that track (as well as to a slightly lesser degree, “In dark trees”); and I think what appealed to me was that they were atmospheres or moods – of course, I didn’t think about it as being important, but it was the first abstract music I responded to, and in particular, to the sound of those pieces, which are very warm. It’s not like I listened to the LP a bunch of times and became an Eno fan… that would happen much later, but every once in a while I would listen to it the LP, and try to make sense of it. It’s kind of like the quote you offered about Samuel Delany, because I needed to keep re-visiting it because it confused me and while I had no context or language to understand where it was coming from, I still wanted to find my way in it…

It seems pretty unusual that as such a young person you actually made the effort to try. It suggests a level of openness. So, back to the sound of recordings…

People don’t talk much about the sound of punk recordings, and certainly there aren’t a lot of distinct approaches to recording with a lot of punk records, but if you listen to the first X or Gun Club LP’s – both on Slash, the sound is really different than, say, never mind the bullocks… the Slash recordings are full of energy, but sound somehow clean and kind of warm… it wasn’t until the post-punk scene where bands like PiL, Joy Division and Bauhaus were experimenting with sound, that I started responding to sound itself – and it was the same with Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle. But PiL was especially influential – especially “Metal Box” – which had a HUGE impact on me – as well as the Clash’s Sandinista, just in terms of how the music was expanding and feeling less influenced by the scene… those two records are so different from each other stylistically – truly independent – both embracing experimentation and to different degrees influenced by dub – they both point to different potentials towards the future. I think even bands like Felt, Eyeless in Gaza and Orange Juice also had very particular sounds. One record that resonated deeply was Martyn Bates 10″ Letters Written, from 1982. It is mainly voice and, I think, a synth organ, and it is one of the most beautiful melancholy lonely records I have ever heard, and at that time in my life which was quite a disaster, I felt so connected to that music, maybe deeper than to any record I’d heard until then, and my response to that record was the beginning of moving away from punk… and I was kind of lost trying to find music to fuel my interests.

Public Image Limited – Metal Box “Memories”

Martyn Bates – “Letters form yesterday”

Martyn Bates – “Letters form yesterday”

What stands out to me here is how you identify a move away from aesthetics being dictated by “the scene,” which I’m interpreting as the sort of social aspect. Of course genre is often very much about community and sociality and exclusion as much as any formal aspects or “the sound” itself, but it may also hint at why it’s so hard to talk about various strains of experimental music as having a coherent community at all.

I think what you are getting at is very important, because while the music scene generates the culture, at some point there is a split, and for me it was twofold, the culture of punk was getting violent and codified, and the music felt overly predictable (I’m generalizing of course)… honestly, I wasn’t looking for culture to be part of, feeling growth could come from isolation, and that’s really when i started making my own recordings – again without any context, but trying not only to find music to like, but also music to make.

Another monumental experience happened around that time, a friend’s dad had tickets to a Philip Glass performance and he couldn’t go so he gave us the tickets. Once again, we had no context and when the concert started – I believe it was a two piano piece or two organs, and all I remember was them starting and ending, but during the performance I was transported to another place… truly. I have to say even though that was a life changer, I’m not really a fan of Glass’s music, but it got me to Steve Reich, which was huge… also, around 1984, I discovered Eno’s Obscure label and I bought a copy of [Gavin] Bryar’s Sinking of the Titanic – not knowing how much the other side of the LP –Jesus Blood ever Failed Me – would also be HUGE for me, this idea of using a “field recording” within the context of a work, and also the repetition. That record really opened the door to my working in a quiet way. (and if I can bring up integrity again, the version with Tom Waits singing really destroys the integrity of the original entirely…). then, in 1987, I was driving in the car with my mother, listening to the radio and the announcer mentioned the that [Morton] Feldman had died. I didn’t know Feldman’s work at all, but I remember telling my mom to go in the store to get what she needed, while I remained sitting in the car alone and listening to this music, which was a very quiet and seemed from another world, yet had en enormous impact on me.

It’s interesting to me how at that time media circulation was a bit more closed than it is today (though of course radio, portable tape recorders, cassette tapes and even xeroxed zines were huge innovations and contributed to new circulations not available to earlier generations) but that this closed-ness made possible the almost context-less encounters you had with Eno, Bryars, Glass and Feldman. In many ways, looking back from the present, these seem serendipitous, though I’m sure there were plenty of other kids who were into punk or classic rock or something who had or would have had very different experiences. Or even the friend you went to see Glass with.

2011, performance at cafe oto (i use the laptop only for video, which is filmed the day of hte performance and used as visual/sound loops during the performance. offering documentation of private performances earlier in the day – i don’t love having a laptop on my table, but the use of video for me is awkward and quite difficult, and so it seems worth pushing)(photo by helen of sound fjord)

Yes, and I think if we had the internet we might’ve found out about things sooner, but the ease would’ve made

everything feel less special – and the important thing was that I was making connections between things, rather than “links” determined by a machine or someone else. All true subcultures start small, as do all alternative cultures – and I mean true alternative cultures. What was different was that you had to be in a certain location, and you weren’t able to mimic the dress style or the music unless you had been there in person – or at least were surrounded by physical things that were hard to find… records, zines, even t-shirts… we made Damned t-shirts because we could not buy them anywhere. I just searched “punk rock t-shirt” on ebay you g

et 27,644 hits!!!!! On one hand that is super cool, on the other hand how does one become part of a true alternative culture with virtual friends who form a virtual community, where everything you need to join the club is a “click”

away. I hate to sound like an old guy, and I’m not trying to make a value judgment, but I believe that such a path was different, both physically and emotionally, and I believe that it made everything feel a lot more important and a lot less disposable.

Hm, it’d be interesting to think this through further. I don’t think virtuality necessitates an inauthentic community. But certainly, in the sense of digital mediation, it is much harder to imagine cultivating anything that can be sustained over long periods of time. Points converge and trends pop up and burn out almost as fast (particularly in the already fragmented space of electronic music, cf. #seapunk, witch-house, PBRnB). The obsession is with novelty for novelty’s sake, not with fixed identity or any sense of cultivating a style or craft. How did diasporic communities, like the Jewish people for instance, maintain a shared sense of identity across time and space without modern communication? If I had to answer I’d say: Ritual. Of course modern subcultures are far from having this sort of fixed identity, but it does but the coming together in a different context, a sort of spiritual and ritualistic beyond merely social, or at least at its best it is this. So then, I wonder, how does listening to music alone at home or anonymously via headphones impact this ritual? It becomes very alienating. Literally disorienting, people dip into and out of things in a shallow way, and even though some of us may treat the Internet as a godsend to delve deep into the archive, most people don’t seem to really explore and learn about what has come before. Anyway…

Sure, I understand what you are saying, but we all know that conversations via email, facebooking, etc. are quite different than humans in a room. There’s a freedom in the invisibility, and a willingness to offer information to others online that might be quite different than sharing in person – politicians sending phone pictures of their genitals without a worry, who would never pull down their pants in public…. funny, yes, but it also shows that there is a huge difference in being in a room with people and sending a text… and hence, I think there is an enormous difference in an online community and a group of people meeting every weekend at a club…

In terms of moving away from what I knew, the question became how can you determine your trajectory if you don’t know what you are after? I certainly didn’t know. When I got out of the punk scene I started listening to a lot of song stuff, again coming from the UK, with labels like Rough Trade, Cherry Red, Postcard, Factory, etc. a lot of that music had a melancholy quality that I responded to… and it wasn’t until maybe 1984 or so that I started moving outwards – discovering Steve Reich’s Desert Music (because I liked William Carlos Williams’ writings), which led me to Music for 18 Musicians, and eventually to Meredith Monk (because she was on ECM… ) and Stephan Micus(who was also on ECM), and just like everything else, I had no context for these artists at all. And it wasn’t until maybe a year later that I heard about minimal music – finally contextualizing that Glass performance I experienced. Now, I don’t listen to any of those artists, but they all helped get me to where I am, and in one way or another felt sympathetic with my own responses to music (as well as the Chicago Art Ensemble)… and the list goes on, but it was all a game of telephone, for if I liked something on a label, I would buy something else, and then after 2 or 3 releases I found some kind of context. It wasn’t always right or good – there are a lot of ECM records I hated… but Meredith Monk’sTurtle Dreams was just as important to me as PiL’s Metal Box.

I almost want to ask about California. The LA punk scene was pretty removed from what was going on in NY and London or even DC, even though later that scene became very well known and appreciated. But there’s something about California, maybe being so far away from Europe, that seems to have allowed room for all sorts of creative flourishing in the States, from avant-garde music to poetry. You’ve traveled all over the world at this point, but has LA always been your home base? Anything about LA as a city, or as a medium of sorts, that you might care to talk about?

I think there has always been a strong difference in west coast aesthetic and east coast aesthetic – in painting, music, writing, etc. and I consider myself very much aligned with the history of west coast art – looking at someone like Bruce Conner, who worked in a variety of mediums, never really exploited a consistent style, left the scene, returned, etc. I think the beauty of Los Angeles as opposed to NY, at least in terms of history, is that the scene here has always been smaller and much more casual, and hence less of this overriding feeling that everything is a big deal. You can disappear in LA without really disappearing, and there isn’t that feeling that you have to be at every opening or you will miss something. Painters like Lee Mullican and Gordon Onslow Ford made paintings with cosmic intentions, inspired by American Indian culture – and in NY, at the time, they probably thought it was hippie painting (although that was before the term hippie existed). I think about the Screamers in relation to DNA… it sounds like a cliché, but historically, the east coast has been more cerebral, and definitely more academic… of course, these are huge generalizations, but even the difference between jazz in the 40′s and 50′s between east coast and west coast, you can clearly see two very distinct sensibilities. Even with Hollywood, this is a laid back town. It is as a car culture, meaning you are generally alone and more disconnected from “noise”. A car is like a moving cave, the NY subway is like a moving crowd… I’m not sure about location, but certainly the way one lives life fuels their approaches to art making (and similarly, art also fuels one’s approach to life). If you are in a place your whole life, it is not just a place, but an incredibly strong influence. People talk about the light in certain places, but it is more than that, it is how one lives in a location.

DNA – “Not Moving”

Of course you’re not interested only in sound, but you are also a visual artist, you work in many media, at Suoni you used sound and video together, and you’re also rooted in the academy, in your training and working as a professor. How did your sound practice begin, and how did it evolve related to your visual practice? Do you have techniques or approaches that transcend medium specificity? Or does the materiality of the medium (a lo-fi tape recording as it is, the interface of your cheap pedals, etc) steer the boat? I realize now this question sounds almost naïve, there must be some of both, or maybe there’s no system underlying it at all.

Well, there’s no naive questions – nor any bad ones. My method is not exactly codified, so it is a very relevant question, especially as it is somewhat complex. But first, I must attend to the first part of your question about me being “rooted in the academy”… which is quite funny, as I’ve never been spoken of as such. My relationship to my education was quite contentious, probably for all the reasons I mentioned above. I was interested in pursuing personal vision, which is not always compatible with the goals of a program. I had a very difficult time with the readings of Beaudrillard and Deleuze – as I was mostly interested in Rilke, poetry and literature like Hamsun, Hesse, Mann, etc. and I didn’t fit in. At the time, the late 80’s, people were moving towards spectacle and I was moving towards quiet. I fought really hard against “the academy” in school, and was nearly kicked out of school for it. And this is where these ideas become important – because you don’t become an artist to please other people or to conform to the thing of the moment… at least in terms of what being an artist meant to me, so in terms of a student, I would say that in many ways I bypassed the academy, as I was able to succeed in doing what I felt was important, rather than what expected. it was quite a difficult experience that made me much stronger once I was out in the world.

2012, performance at human resources in los angeles, this is the first time i’ve used my father’s guitar in a performance. (photo robert crouch)

In terms of my being a professor, well, I really feel it is my duty to work with younger artists and to push them to think about these larger issues of integrity and fighting for what you want to do. Graduate school can suck the life out of a student, particularly if they are already thinking about being successful; so I feel it is my job to go in there and to help them empower themselves, so they can fight back and experience life in a little messier way, so that it becomes real. They seem afraid to trust themselves, and they want success without really understanding what success demands of you. And more than anything, I share my own career with them. I’ve been out of school for nearly 25 years, so I have a lot of experience behind me – both good and bad. In my own experience, teachers like to create distance, and I try to break that down.

In terms of my practice, well, I studied fine arts with a major in painting -which ridiculously meant I had one true painting class in 6 years of school! I had been working with sound since I graduated high school in 1982, but mostly writing songs. It wasn’t until 1987 or so that I started working with ambient sounds and electronics and abstraction. What took a long time was to acknowledge that the sound work was part of my practice – not something separate. In 1993, I finished a group of sound works and as I was about to drop the tape into a very full drawer of tapes, I felt like I had to acknowledge the sound was part of my work. It was a freeing moment, which opened the door for the work to continue to open up and to defy expectations. So eventually text, film, sculpture, performance… became part of the work as well. I don’t like being considered a visual artist or a sound artist… and tend to simply consider myself as someone who makes things in a variety of forms.

Well, maybe ‘rooted’ was the wrong term. But, still coming through graduate school and teaching, you seem to be much more able to articulate what it is you do, and think conceptually, than a lot of other artists I’ve encountered. (Not that every artist has some obligation to be able to really speak articulately about their work, I suppose.)

What’s funny about this is that I am teaching graduate school right now, and I just told my students to try to write like they speak… and I ended up writing them a manifesto for writing/speaking about their work, with rules such as: clarity, simplicity, honesty, etc. they are constantly griping because their other teachers are making them write in a very specific academic way, which I think is too detached from life, and which fuels distance, rather than intimacy. an artist statement isn’t to show how smart you are, it is to convey what your work is about, where it comes from, and why it matters.

So I create games for them, like Eno’s Oblique Strategy cards specifically towards a critique situation, so that they can begin to think differently – to break away from learned habits. They write the way they write because they’ve been told it has to be a certain way; so I believe it is my job is to tell them that what they are being told is simply not true. The purpose of articulating your work is not to baffle folks into thinking you are smart, but to articulate what you do, clearly. A statement is an opportunity to share, and that sharing should be as generous as possible. I’ve spent a very long time trying to to articulate what I do with enough clarity that my mother or my neighbor can understand me.

A lot of people who come out of academic culture seem to enjoy speaking or writing in ways that create distance, talking down to people; but I have no interest in making someone feel as if they don’t know enough. I’m interested in offering permission, so that anyone can respond to artworks or music on their own terms, rather than my own – so that their responses can fuel conversations – perhaps, them showing me something about the work. Of course, sometimes it helps to know context or histories, but sometimes you bump into a record like Another Green World and you don’t need an instruction sheet as much as you need to simply be patient and trust your ears and your insides….

In specific terms, a source generally dictates my engagement with it – as well as determining the tools. My recent LP for ini.itu was created through recordings and objects sent to me by Sylvain, who runs the label; and the stuff he sent me was pretty stubborn. At first I could not find my way to doing anything with the materials, and then eventually I created 3 or 4 tracks that utilized the material but the resulting tracks felt too familiar, and I felt as if I wasn’t acknowledging their characteristics. When you have been working for so long, you need to find ways not to get in the way of the material you are working with, so I threw those tracks away and started over, and finally we came to a meeting point – between myself and the materials, and slowly the tracks evolved into a record. What excites me is that feeling that I could never have made this record without these materials – so that it feels as if their voice is present as much as my own. It’s a different kind of improvising when you aren’t improvising with a person, but you still must find a place of sympathy. Sometimes this does come through scores or plans, but those aspects are usually collaborating with improvisation… no different than Cage pulling the I-ching or Eno’s Oblique Strategies or Fluxus scores… just words suggesting moves that would not have come about without them.

Part II of Sound Propositions with Steve Roden will be published next week, in which we talk about aesthetics, technique, and Steve’s relationship to technology.

it seems a necessity, as active listeners, to become sensitive to these things in the world around us that the german poet rilke called “inconsiderable things” (the things from everyday life that most people don’t really pay sensitive attention to). standing on a street corner, listening to the sounds of cars approaching and then passing, the repeating crescendos resemble the sounds of ocean waves or the patterns of gentle breezes. these sounds do not only move around us; but also through us; and with sensitive ears, we begin to hear the world differently. we determine the possibilities of such “everyday” sounds for ourselves, and depending upon the depth of our attention to them, all sounds have the potential to evoke profound experiences through them.

-Steve Roden, Active listening

This is the second of a two part conversation between Steve Roden and I, conducted between June and December of 2012. You can read the first part here, in which we discuss Steve’s influences, growing up in LA’s nascent punk scene, and his approach to creativity in general. Below, we discuss his technique in more detail, his relationship to cheap technology, and his approach to live performance.

Once again, I find it most appropriate to begin with Steve’s own words. As diverse as his body of work is, and as open to possibility as Steve is as an artist and thinker, there is a serious thought and philosophy uniting his work. I think it would be too easy, and reductive, to call this “lowercase,” though the metaphor is a compelling one. Lowercase is about not screaming for attention, but a self-awareness that one’s activities are for those who put in the effort.

In addition to his work as an artist working in multiple media, Roden has also written a number of essays that explain this philosophy. He’s written about how he is not in anyway a technical person, but uses technology to his advantage by focusing on a restricted set of parameter specific to the medium in question. These essays about his basic use of recording equipment, tape, his first foray into digital recording, and more can be found at his website www.inbetweennoise. The actual techniques he employs are rather beside the point, so this interview dwells more on the concepts and ideologies, if you can call it that, and the systems he constructs and uses to guide his work, almost like scores. The creative spirit animating his work is scene in the processes he sets up and the ways in which he navigates within these closed systems.

The figure of the bricoleur, or amateur handyman, perfectly encapsulates for me the nature of Roden’s talents. Bricolage is the art of making do with what’s at hand, not settling for less but maximizing the potential within any circumstance. In The Savage Mind Claude Levi-Strauss describes the ‘bricoleur’ as “adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks; but unlike the engineer, he does not subordinate each of them to the availability of raw materials and tools conceived and procured for the purpose of the project. His universe of instruments is closed and the rules of his game are always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand,’ that is to say with a set of tools and materials which is always finite and is also heterogeneous because what it contains bears no relation to the current project, or indeed to any particular project, but is the contingent result of all the occasions there have been to renew or enrich the stock or to maintain it with the remains of previous constructions or destructions.” When Roden translates poetry from a language he can’t read, or uses the indecipherable notation from Walter Benjamin’s notebooks as a compositional score, or gently coaxes inanimate objects into dialogue, I can think of no better description than that above. His method foregrounds the act of production as production, a true love for creation itself that is both serious and playful all at once.

Architecture also serves as an important influence and inspiration for Roden, no surprise considering the scale of architectural development in the 20th century and its explicit acknowledgement of its influence on ordering social relations. Goethe famously said “Music is liquid architecture; Architecture is frozen music.” Perhaps it’s the ability to work within structural frameworks imposed by material conditions that draws this comparison, but Roden seems to take influence from the experience of physically navigating the space itself. He actually lives in the last remaining Wallace Neff “bubble house” in North America. Neff is best remembered for his Spanish Colonial Revival style mansions built for LA’s elite, but he designed the bubble house as a low-cost solution to the global housing crisis. In a 2004 interview with the LA Times, Roden said “It’s a little like being the caretaker of someone’s project. …If someday someone found all my work at the flea market, I hope they would take care of it and read some catalogs and try to do the right thing. This house is something Neff believed in. I feel so strongly about his dream of what this thing could have been.” Roden also has a special relationship to the work of architect RM Schindler. Roden declared the Schindler house in LA to be his “favorite space in the world,” a space in which he made a special in situ performance and recording. The modern design of the home is not just a question of aesthetics, but also how aesthetics and design influence social space. Absent any traditional living room, dining room or bedrooms, the house is meant to be a collective living space shared by multiple families. Both architectural works speak of a time in which our great thinkers hadn’t exhausted the dream of utopia, and understood how aesthetics and ethics intertwine, an understanding also reflected in Steve’s work. A recent blogpost on Roden’s site hints at this relationship as well.

A recent blogpost on Roden’s site hints at this relationship as well.

A recent blogpost on Roden’s site hints at this relationship as well.

A recent blogpost on Roden’s site hints at this relationship as well.

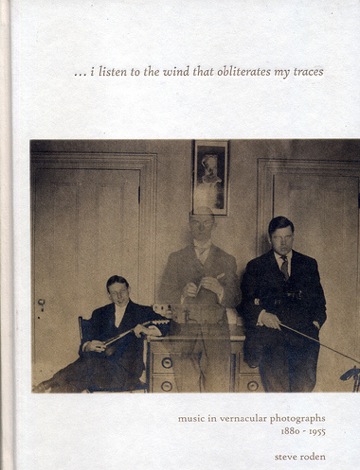

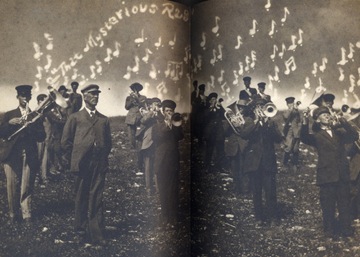

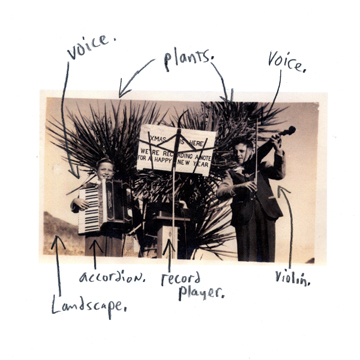

Roden recently released a book [buy] entitled , … i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces that compiles early photographs related to music, a group of 78rpm recordings, and short excerpts from various literary sources that are contemporary with the sound and images, all culled from his personal collection. The accompanying CDs collect a variety of early recordings, including amateur musicians, long-forgotten commercial releases, and early sound effects records. There is no explicit narrative connecting the parts –that would be too confining and linear- but the implication is that our we collectively shape our culture as bricoleurs as well. It’s a beautiful realization. (Joseph Sannicandro)

A playlist of the songs mentioned in these articles can be foundhere.

Are you familiar with (French sociologist) Bruno Latour’s concept of Actor-Network Theory? The way you describe working with objects reminds me of this, in some way, it’s as if you are improvising with the (non-human) objects, as actors, rather than using them as instruments. Is this fair?

I don’t know Latour’s idea for acting, but yes, I view my work with objects as collaborative. I don’t force them to fulfill my needs as much as I try to let them lead me somewhere I’ve never been, so that the object maintains its integrity. I’ve often spoken about a review I got a long time ago about a CD I recorded at a space in LA, designed by the architect RM Schindler. It’s my favorite space in the world, and when the reviewer wrote about it he said the disc was great, but it could’ve been made with anything, which really stung me because he didn’t understand how deeply the space determined my approach, or the way my eyes, hands and ears collaborated in suggesting moves. These things are silent; they don’t offer themselves up nakedly as if porn – but they are determining the processes that occur behind the scenes. Because of my history with the house, I forced myself to arrive without a plan… thus the initial recordings came about through this conversation with the house; and while I could probably remake the sound of that record with a computer, hairbrush and a potted plant, my engagement with the space and its qualities, were what fueled all of my decisions, and if I had made recordings at the house next door, the piece would’ve been completely different.

Steve Roden live at the RM Schindler House

That reminds me of something I read by Michel Chion, probably from “Invisible Jukebox” feature in the Wire. He said he felt that field-recordings were kind of beside the point, because at heart the sounds you’ll capture in Paris aren’t so different from the sounds of another city, unlike photography of its fabled roofs or streets or what have you. I was really shocked, you know, because here’s this big critic and figure in sound studies, and he totally misses the experiential aspect of how recordings come to be made. There is more to a recording then the physical, material impression or information. Maybe he never encountered Dewey’s Art as Experience.

Yes, some people think that if an idea fuels a work and is must present upon the surface of the object. This is such a literal approach, like a joke, first hearing a set-up and then a punch-line and done… I’m not so interested in a kind of perfect resolve; in fact, I’m much more interested in open ended things that do not resolve easily, as I feel that it allows meaning to be built through one’s experience with the artwork, object, song, etc.

Your work also seems to break a lot of the “rules,” or defy the doxa at least.

For instance, you improvise, but mostly against yourself, not in dialogue with others. (Though your duo with Seth Cluett was interesting to watch as a contrast to this). You utilize cheap gear, don’t monitor when making field-recordings, translate poetry from languages you can’t read, etc, and manage through these practices to produce engaging work nonetheless. You’re academically trained and currently a professor, but continue to go against the grain. At the talk you have at Suoni in Montreal last year you mentioned being inspired by artists who work on the margins. Did you set out to do things your own way by choice or by necessity?

That’s an interesting question. On one hand I would say not many people would set out to work on the margins by choice, but on the other hand, if you want to be left alone to do your thing, the margins might be a haven. I look at someone like Harry Partch, and how his music is absolutely his own, and I think that because of how “other” it is, he has cemented his career as being on the periphery (and in some sense, Feldman did the same thing). For me, what’s important is being true to the work – which is very different than being true to the audience. Expectations are deadly, and both Partch and Feldman were unwilling to tuck the difficult parts away for the sake of being in the “center”. If Partch cared, he’d had turned to traditional tuning, and if Feldman cared, he’d have composed shorter pieces with more dynamics and narrative. I hate to keep going back to the same things, but I would never have made any of the works or had the approaches that you are asking about if I wasn’t part of the punk scene; because that moment was so much about pissing on talent and embracing the creative act – jumping in the water without needing to know how to swim. It’s all about ideals… and trust. so if I am unwilling to compromise my practice, then i must own my place on the margins. Honestly, I think it is highly unlikely for an artist to determine where their work fits in relation to the center or the margin, and there are certainly folks who get to straddle both at different times in their career… such as Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music and Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Wild Side”… you never know where the work will land…

I use cheap electronics because they are limited in terms of options – so I have to really think or feel when I’m performing with them, because I don’t have a million choices or plug-ins. I have always wanted the live experience to be live – which means very little preparation and being in the moment of a potential disaster. I’ve played with people who literally open an iTunes file and press play. On one hand this is great – the sound is pre-set, the mix, etc. but it isn’t live music, and it doesn’t offer any of the tension of live music, nor the creativity of a live performance, it is simply sharing music.

Which can be great if the venue is really special and the audio-system is really unique and offers something quite removed from simply popping a CD in at home, but I will come back to this later.

Absolutely! I’m not making a value judgment between live performance and tape performance, but they certainly offer different expectations and experiences. Part of the reason I recently started improvising with video is that it offers more complications in a live situation and seemed to offer less control. At the Suoni gig someone came up to me afterwards and criticized the performance for using low production quicktime files, but what he was really criticizing was that the films were not crisp clean hi-end production. For me, the medium – video shot a few hours before the show – offers the visual immediacy of improvised recordings, and it was important not to dress them up as “films.” The fact that they were crude and repetitive and of the moment – just like the sound – was indicative of the whole process of improvised performance. truthfully, he didn’t like how “crappy” they looked, but for me, they spoke in a language appropriate to the performance situation, and I’m not adverse to the vulnerability that such decisions offer.

You talked a bit earlier about ‘jumping in without knowing how to swim,’ and also about the tension that animated live performance, and I think improvisation in particular. So, I think my follow up has to be, how do you reconcile your ‘studio’ practice with your live practice? Not that you have to, but what I mean is, unlike painting or visual art/gallery art, where a ‘finished’ object is presented as something closed, generally, live music has a performative dimension, a temporal dimension, that the performer responds to in an open way.

My first live gig was a total disaster. I had just finished my first CD in 1993, and I had no idea what to do live. I knew very little about gear, and my recordings at that point were mostly multi-tracked, using mostly acoustic objects – Turkish flutes, homemade instruments, old toy instruments, stones, chairs, etc. But it was all related to working in my home studio. So for that first live gig, since I didn’t even have a delay pedal, I brought a cassette machine with me, and I had some of the sample loops from the CD on the cassettes and I tried to improvise over the loops. The problem was that it was kind of like experimental music karaoke… there was absolutely no life to it! For many years my visual art practice was limited to painting – no drawings, no sculpture, no film, etc. When I finally added drawing to my practice it was because I had finally discovered what I wanted from it – to experience an activity that drawing could offer me and painting could not. This was a huge moment, because it was about the integrity of the medium and/or the situation of making. So I began to think that if I was going to do live shows they absolutely had to embrace the temporal, and they would have to be absolutely LIVE. So I got myself a delay pedal, someone made me a few contact mics, and I just started to mess around with this stuff.

I don’t like playing live very much, I don’t like being the center of attention and for the most part, I’m happier with the results when I make records – in fact, in 19 years of releasing stuff, I’ve never released a live recording (although I’ve posted some things online). Nonetheless, while I don’t “like” performing, the potential in that discomfort is kind of wonderful and a lot of things happen live because I’m so uncomfortable and I’m trying to make sure the thing I’m creating isn’t going to implode – it’s absolutely the most focused activity because there is an audience – which scares the hell out of me. A risk in a live environment means so much more than a risk in the studio. So to answer your question, I don’t totally use the same tools in the studio and live, but even more so, I try to make sure that the activities are medium specific.

a recording session in the garage/studio working without electronics, other than some small cassette recorders (2011)

It seems to me that because, before recording technologies were developed, music was the only sonic art, with the possible exception of the complicated case of spoken poetry. Recordings of music tend to be thought of as capturing something live. (Sure, there was ritual music, and folk music, music for entertainment and music for contemplation, music for work or for art. But this is all still rooted in some sense of ‘liveness.’) Even though this isn’t quite true (and was never true), in fact recording is always in some sense a studio practice- even in 1948 when Muddy Waters plugged in and sang into microphone we’re already playing and listening differently and recording responds to this- the baggage of music being a ‘performative’ art rather than a ‘studio’ art hasn’t quite gone a way. And I think a lot of sound art and experimental music is implicitly or sometimes explicitly challenging this, just by incorporating/instrumentalizing media that was conceived of as recording/playback, be it tape music or with a laptop. I’ve seen a lot of folks trashing on guys like Skrillex for not being “real” musicians. Not that I want to defend Skrillex, but its striking to me how much people seem to miss the point.

I have no musical knowledge or skills either, and I would never consider myself a musician – a composer, maybe – but never a musician. I don’t know Skrillex, but I find those kinds of arguments to be pointless. Some people would rather listen to a drunk singing his ass off out of tune, while someone else would rather listen to the band Rush… if you are looking for technique, that is one thing. If you are looking for something real, it might come from an amateur… I mean how does one define a “real” musician… it’s not like Son House learned to make music in a conservatory.

Son House – “Grinnin’ in your face”

But then, there must be something at work if even after half a century of tape/computer music, or hell, a full century after Russolo, people still can’t seem to distinguish between listening to something in your car and experiencing it with a room full of strangers, dancing and celebrating together, or sitting and contemplating together. Who cares, on some level, what the guy on the stage is going? Of course plenty of artists respond to this by playing out of sight, or in the dark, or blindfolding the audience. You do have distinct practices that fall all over the spectrum from studio to performance, so I’m curious to get your perspective. Maybe I’m wrong to draw that distinction at all, but I think there’s something to it.

Early on, I did some performances where I was behind a curtain, etc. But it tended to draw more attention to the “missing” musician than having one present. I tend to close my eyes when I hear music, but even with someone like Francisco Lopez, who demands blindfolds at times, I find that to be a kind of distraction from listening simply because of the vulnerability and the anxiousness the blindfold evokes. It turns the thing away from pure listening. I have seen laptop players sit in the audience, and I’ve seen them sit on stage, and again, I don’t think you can make generalizations based on someone’s tools. Carl Stone is one of the most energetic and engaging performer i’ve ever seen, and ever since he has downsized to a laptop his performances remain gritty, human and exhilarating!

Carl Stone –“Shing Kee”

In terms of “what’s he doing?” I think people respond to my performances because they can see that I’m doing things with my hands, and it is very intimate and somewhat primitive – so there is usually a disconnect for people in relation to how these poor materials are creating such sounds; but if you approach performance from a place of humility, I believe that people feel less distance from you, and perhaps the gentle nature of my live work offers an entry point into dissonance or abstraction that would seem aggressive if it were loud. I don’t think about live music as a narrative – more like creating a space… it is a building process, but I don’t have a plan when I start. Sometimes I have cards or cues to push myself away from comfort zones.

my gear and stephen vitiello’s gear for a performance at the rothko chappel, related to an exhibition called “silence” (2012)

I know your working method changes based on the project, the materials, the site, its architecture, who you’re working with, etc, but, can you walk us through a sort of typical engagement with your equipment? I know you resist that fetish relationship, but at the same time you’ve developed a relationship with some pieces, with your two old delay pedals, with a particular type of mixer, and so on. Do you run an FX send/return? You don’t monitor your mixing with headphones when you’re performing, is that right? How about in the studio, do you mix on headphones?

Basically, my two biggest tools are my mixer (an old 8 channel Mackie) and two guitar pedals (both the same – a DOD dfx94 – I think it holds 6 or 8 seconds of sound, and it’s called a sampling delay. You can layer sounds in loops, but the oldest starts to degrade every time you add a new loop. You can also change the pitch of the loop by speeding it up or slowing it down. Both of these tools are very very limited, and that is what I like about them. When I do a gig and someone brings me a 16 channel mixer with multiple aux sends, etc. I am totally overwhelmed and generally it is a disaster, as I don’t understand mixers in general, I just know my own since we’ve been together for nearly 20 years… Recently, I purchased a couple of high end sampling delays and I realized they did too much… which got in the way of the simplicity and limitations. That’s why I consider these two my instruments, more than the things I make sound with, because they are the only pieces of gear I feel totally familiar with, as if they were extensions of my hands.

The other most important tools are contact mics. I use piezo buzzers to make them, and I use the ones in plastic housings – which means they don’t have the sensitivity of true piezos, but I like the way the plastic housing sounds, and you can dunk them in water or drag them along the ground, put them in your mouth, and the little hole in the plastic offers a ton of options.

The variables can include a record player, pine cones, stones, recordings made in the space, field recordings, my voice, a lap steel guitar (rarely anymore), harmonicas, etc. One thing I NEVER use is reverb. Live, I simply pick a sound or object to start with and move forward adding and subtracting, making decisions mostly improvisationally. If I feel like I’m running on the fuel of habit, I try to find ways to disrupt things.

In terms of headphones, I never wear them during performances – which would suggest that I’m hearing something entirely different than everyone else. That seems total detachment from the audience (unless they too are all wearing headphones!). For field recordings, I also rarely monitor what I’m recording with phones as well, as I am mostly interested in the document and how it can become “useful” regardless of what it sounds like – it’s more about capturing air than sound, to bring some of the landscape into the recording mechanism, like capturing the landscape’s aura. I know I’ll never be Chris Watson with my field recordings, but I am also not looking to capture nature as it is in life. I’m interested in how the recordings can trigger new experiences. Field recordings for me are mostly a cache of material to be used. Now I make a lot of recordings with my phone, and I think if I made super high quality field recordings I’d be afraid to play with them as freely as I am able to do with the sort of wonky recordings I make.

Even with your project on Walter Benjamin, it seems like you arrived and let the idea take root through a dialogue with the unknown. I’m reminded a bit by artists like Gabriel Orozsco, this idea of the artist who just travels around with nothing but a notebook and a toothbrush, his studio wherever he finds himself. Does this idea of an “artist” resonate with you?

With this it is twofold, I get my inspiration just about anywhere or anyhow, might be a book a place an object a season a word a color, etc. and traveling around with nothing but a notebook and a toothbrush is basically, for me, a form of inspirational gathering and elaborating through writing… but the work generally occurs in my studio, and I am not someone who can really make work in hotels or on airplanes, etc. I still have that need for a studio space, mostly because I’m incredibly messy! So I feel somewhat in between an old idea of an artist slaving away in solitude in a studio and someone who travels a lot and who gathers a lot from traveling. Clearly, my work would be much different if I never left home (for better or worse).

What advice would you give to readers interesting in experimenting with sound. Rather than: the manual says this is how to do something, these are the scales or modes to learn, or such and such a controller mixing together stems in Abelton, etc etc. Was it just trial and error, resourcefulness, getting to know the gear you had available?

Most important story: Eno on the radio talking about working with the DX7 synth, and how everyone was gathering sound files and trying to build libraries, and he decided instead to work with the presets – horribly cliché and boring sounds… because he was interested in how a dead end fuels creativity. That resonated with me very very deeply. What it emphasizes is not how great your gear is, but how you approach something creatively – a source, an idea, a form, a limitation, etc. so that it will unfold!

A lot of artist seek works that fulfill their expectations from the beginning – an idea appears and is realized. I have no issue with that as a method, but it is not for me. Certainly, I’m using physical material – say with Benjamin’s notebooks – but I don’t have a plan at the beginning for what will come out of my conversation with this material. I don’t want the sources to have to conform to my expectations as much as i ask the materials to open me up, initially to create difficulty, then to teach me something, and then to push me off onto a path… this is generally not an end point, but one of many beginnings. failure is a necessary part of the process, and I have no idea what will come out of it. working with Benjamin’s notebooks, I never could’ve conceived of a sound piece, a few video works, drawings, and now beginning to find a way towards paintings (nearly a year later). if I knew what I was looking for, I would not see anything else (like driving in a car and never looking out the window until you arrive at your destination – for me, the journey has the most value, in fact sometimes even more so than the result!. But of course, it is a slow process waiting for voiceless things to speak.

John Cage would have been 100 this year, and of course we’ve been presented with a never ending Cage programming lately. Can you talk a bit about Cage and his influence on you? I remember you mentioned something about realizing a score of his.

Without realizing this would be his 100th year, in January 2011 I began a year long project performing 4’33″ every day for a year. If I thought I knew Cage before then, this certainly took everything to the next level – for I not only performed the piece every day, but also wrote about each realization in a diary (which has been included in a few exhibitions already and which I hope will be published at some point). It wasn’t that different from working with Benjamin’s notebooks (and in fact while in Paris, I performed 4’33″ using one of Benjamin’s notebooks on display at the Jewish Museum as my instrument… so much of my thinking collided in that moment.)

My relationship to Cage’s work grew slowly. First, I knew him as this guy who made music with cactus and noise. I, like a lot of people, assumed his work was mostly situations where the musicians could do anything… but after realizing some scores with Mark Trayle for a performance of Variations II and Contact Music last year, I really learned a ton – and I think you never really know Cage until you’ve realized some of these scores where you have do some drawing and reading and dice throwing to create your own score. These are not free-for-alls at all… because the parameters that serve the improvisation are very fixed and very complicated to “play”. I don’t think I could break down how much that year of performances worked on me, but it was a really wonderful thing to do (and I recommend it to anyone, especially if you can maintain focus).

What’s so fantastic about Cage is that when he went into making visual works, he was so inventive, curious, and willing to try certain things – willing to fail. I think his genius was to maintain that curiosity, in all of his endeavors…

Lastly, many artists seem to cite you as an inspiration. In my interview with Rutger Zuydervelt (Machinefabriek) you came up as an important influence. I’ve also heard Taylor Dupree mention you were an inspiration for him in moving away from the laptop. Any reflections on being on a stage in your career in which you’ve been able to play this role? I suppose I should mention the whole phenomenon of ‘lowercase,’ which you seem to have your reservations about. Labels are always problematic, but was this a rejection of the idea of seeing commonality between artists grouped under this heading?

Funny, this was the hardest question to answer… hmmmm…. how to even approach such a thing… I mean, it is so gratifying to even think that your work or your process has inspired others… its quite humbling. I’ve worked with both of them, and happy that people a generation younger than me find me relevant. I remember some early gigs with Taylor, and me being perplexed at how he could get those sounds out of a laptop and he looking at my table of junk and wondering the same. While he has moved away from the laptop, I’ve (surprisingly) found myself using the laptop in performances to work with video… so the best part of all of this is that we are all still evolving and our practices are allowed to be messy rather than neat and crisp.

In terms of lowercase, I guess you could see it two ways. One would be a bunch of like minded folks starting something (like punk!), but on the other hand you have people who want to be part of something so badly that they create work for the scene (which I’m sure did happen in punk rock as well). For me, I have always felt that it was important to do things your own way, to veer away from the center and to mine some deep personal territory. When we had the lowercase list, people would argue about which movie was lowercase, or book, and it felt like it was working towards conformity rather than experimentation, which drove me crazy. Now I’m waiting for the uppercase backlash!

Thank you so much to Steve Roden for taking the time to ramble with me and have such in depth and meaningful discussions. It was truly an honor to have him take part in Sound Propositions. Roden’s deserves all the acclaim he receives, yet like many unique voices who work in multiple media and don’t fit easily into accepted categories, his work is too often neglected by the mainstream critics and institutions. We certainly don’t have enough of an audience to make much of an impact as far as that goes, but are heartened as outsiders ourselves to have such dedicated practitioners like Steve quietly working away on the margins to look towards.

And in case you missed it, Steve put together this fabulous mix for Secret Thirteen in December connecting 24 7″ records from around the world.

blog

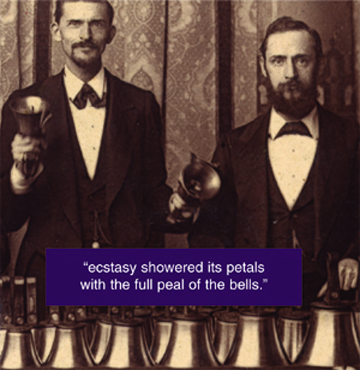

**Hardback book featuring "150 vernacular photographs, paired with 51 songs, field recordings and sound effects on 2 CDs. From the acclaimed sound and visual artist Steve Roden, and designed by the team that brought you 'Victrola Favorites' and the Grammy nominated 'Take Me To The Water'."** "... i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces brings together a collection of early photographs related to music, a group of 78rpm recordings, and short excerpts from various literary sources that are contemporary with the sound and images. It is a somewhat intuitive gathering, culled from artist Steve Roden's collection of thousands of vernacular photographs related to music, sound, and listening. The subjects range from the PT Barnum-esque Professor McRea - "Ontario's Musical Wonder" (pictured with his complex sculptural one man band contraption) - to anonymous African-American guitar players and images of early phonographs. The images range from professional portraits to ethereal, accidental, double exposures - and include a range of photographic print processes, such as tintypes, ambrotypes, cdvs, cabinet cards, real photo postcards, albumen prints, and turn-of-the-century snapshots. The two CDs bring together a variety of recordings, including one-off amateur recordings, regular commercial releases, and early sound effects records. there is no narrative structure to the book, but the collision of literary quotes (Hamsun, Lagarkvist, Wordsworth, Nabakov, etc.). Recordings and images conspire towards a consistent mood that is anchored by the book's title, which binds such disparate things as an early recording of an American cowboy ballad, a poem by a Swedish Nobel laureate, a recording of crickets created artificially, and an image of an itinerant anonymous woman sitting in a field, playing a guitar. The book also contains an essay by Roden." - boomkat

book w/ 2 cds

dust to digital 2011

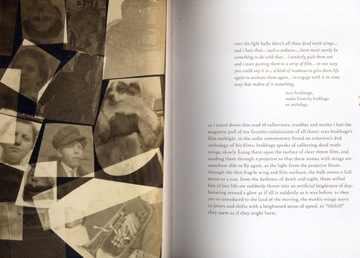

… i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces brings together a collection of vintage photographs related to music, a group of 78rpm recordings, and short excerpts from various literary sources that are contemporary with the sound and images. It is a somewhat intuitive gathering, culled from my collection of thousands of vernacular photographs related to music, sound, and listening. The subjects range from the PT Barnum-esque Professor McRea – “Ontario’s Musical Wonder” (pictured with his complex sculptural one man band contraption) – to anonymous African-American guitar players and images of early phonographs. The images range from professional portraits to ethereal, accidental, double exposures – and include a range of photographic print processes, such as tintypes, ambrotypes, cdvs, cabinet cards, real photo postcards, albumen prints, and turn-of-the-century snapshots.

The two CDs display a variety of recordings, including one-off amateur recordings, regular commercial releases, and early sound effects records. there is no narrative structure to the book, but the collision of literary quotes (Hamsun, Lagarkvist, Wordsworth, Nabokov, etc.). Recordings and images conspire towards a consistent mood that is anchored by the book’s title, which binds such disparate things as an early recording of an American cowboy ballad, a poem by a Swedish Nobel laureate, a recording of crickets created artificially, and an image of an itinerant anonymous woman sitting in a field, playing a guitar. The book also contains an essay by Roden.

“a really cool unexpected book, that my wife gave me. there is great written material and extraordinary photographs. the book also has two CDs of early folk, blues and country.it is by a small press, dust-to-digital.”

richard gere, books i’m reading, in usa weekend magazine

- reviews:

- for full reviews, see the press section of the website,

below are some excerpts...

--- - All Songs Considered: What are you guys listening to these days? Anything you can’t get enough of?

Jeff Tweedy: There’s a two-CD collection, it comes as part of a book, called, I think I’m gonna get the title right …i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces. It’s on Dust-to-Digital records. It’s just this incredible collection of photographs from the 1800s and early 1900s of musicians. And then the two CDs that come with it are recordings of 78s. Some of them are even archival, kind of retrievals of sound effects for movies. Like there’s this one of wind from the ’30s, just really an incredible collection.

jeff tweedy, wilco

--- - (excerpt) “… Both the images and audio were drawn from Roden’s personal collection. If you’ve ever spent time hunched over a box of yellowing photographs or flipping through dusty piles of 78rpm recordings at a flea market hunting for—What? That image or object that speaks to you even if you can’t precisely define why?—Roden is a kindred spirit, and traces is an invitation to get lost with him in this world of mysterious artifacts. In fact, halfway through my first listen, I wondered if I was more attracted to the materials themselves or to the care and commitment it seemed evident Roden brought to their assembly. In the end, I decided it was an equal measure of both. Taken all together, after all, it’s a mix tape of sorts—a revelation of a slice of a hidden past and also a gift from a passionate collector bravely showcasing what has spoken to his own heart.

In an illuminating introductory essay, Roden speaks about the motivations of the collector, where questions of value and what belongs are incredibly personal and fluid, and where motivations, at least as far as music on the verge of obsolescence is concerned, might be traced to a desire to “give new life to voices lying dormant within the tiny confines of dust filled grooves….As the music becomes audible, I am immersed in distant voices singing through both space and time, and in the words of Alfred G. Karnes, I have found myself within ‘a portal, there to dwell with the immortal…’”

molly sheridan, new music box

--- - (excerpt) “The presentation is a delight from cover to cover and I whole heartedly recommended it as one of the finest, albeit unusual, anthologies of the year. Dust To Digital have done it again! (I hate to mention this but Christmas ain’t all that far off and this is book and CD set is just the perfect present. Drop a few hints or get it for yourself and look forward to Christmas morning!)”

red lick website

--- - (excerpt) “There’s something undeniably haunting in Listen to the Wind, in its garbled snatches of historical sounds and the unkempt, chemical strangeness of early photographs left to deteriorate. But there’s something almost overwhelmingly affirming in it too, in its procession of recorded or photographed characters who turned to music for whatever reason – out of desire, restlessness, hope, desperation. Or maybe just to bide the time.”

andy battaglia, the national

--- - (excerpt) “Does it all work? Well yes it does, and I soon found myself sitting back and enjoying the anticipation of just what exactly was coming next. If like me you are getting rather fed up with the sameness of recently issued ‘folk’ albums, then this is the antidote. There are some glorious sounds here and, leafing through the book, I found myself wondering if any of the people pictured in the photographs had actually listened to any of these recordings when they were first issued. I hope so, because this is music that brings a smile to the lips, and that is something that we all need, regardless of time.”

mike yates, mustrad

--- - (excerpt) “Roden’s box set seems closer in spirit to the spiritual designs of wonder chambers. The box set is less concerned with a total vision than the striking juxtapositions of incompatible parts, the haunting stories that emerge from the impossible coalescences.

By contrast, anthologies that document a particular artist or genre or theme with rigor seem closer to curiosity cabinets. Like Roden’s collection, they are also interested in matches, but the complete recordings hope to make them rather than ignite something.

What’s strange is that Roden’s wonderbox actually seems the more complete for the silent gaps it seems to include, while the airtight anthologies seem to have somehow left out the essence of a musician’s oeuvre or a genre’s magic or a theme’s subtleties.”

culture rover