Hidrofonska kartografija: škotski sustav voda kao glavni lik u zvukovnom romanu.

wateroflife.bandcamp.com/album/water-of-life-lp

soundcloud.com/edinburghwateroflife

An art-science collaboration between Rob St.John and Tommy Perman exploring flows of water through Edinburgh using drawings, photos, writing and sound. Part of Imagining Natural Scotland.

Tommy Perman - artist and musician (formerly of FOUND), www.surfacepressure.net - and Rob St. John - environmental writer and musician, robstjohn.tumblr.com - began the Water of Life project in June 2013, aiming to use water as a divining rod for exploring ideas of 'naturalness' in Edinburgh’s urban environment. Water of Life is an alternative travelogue, where water is a conduit for exploring new geographies: field notes from a liquid city.

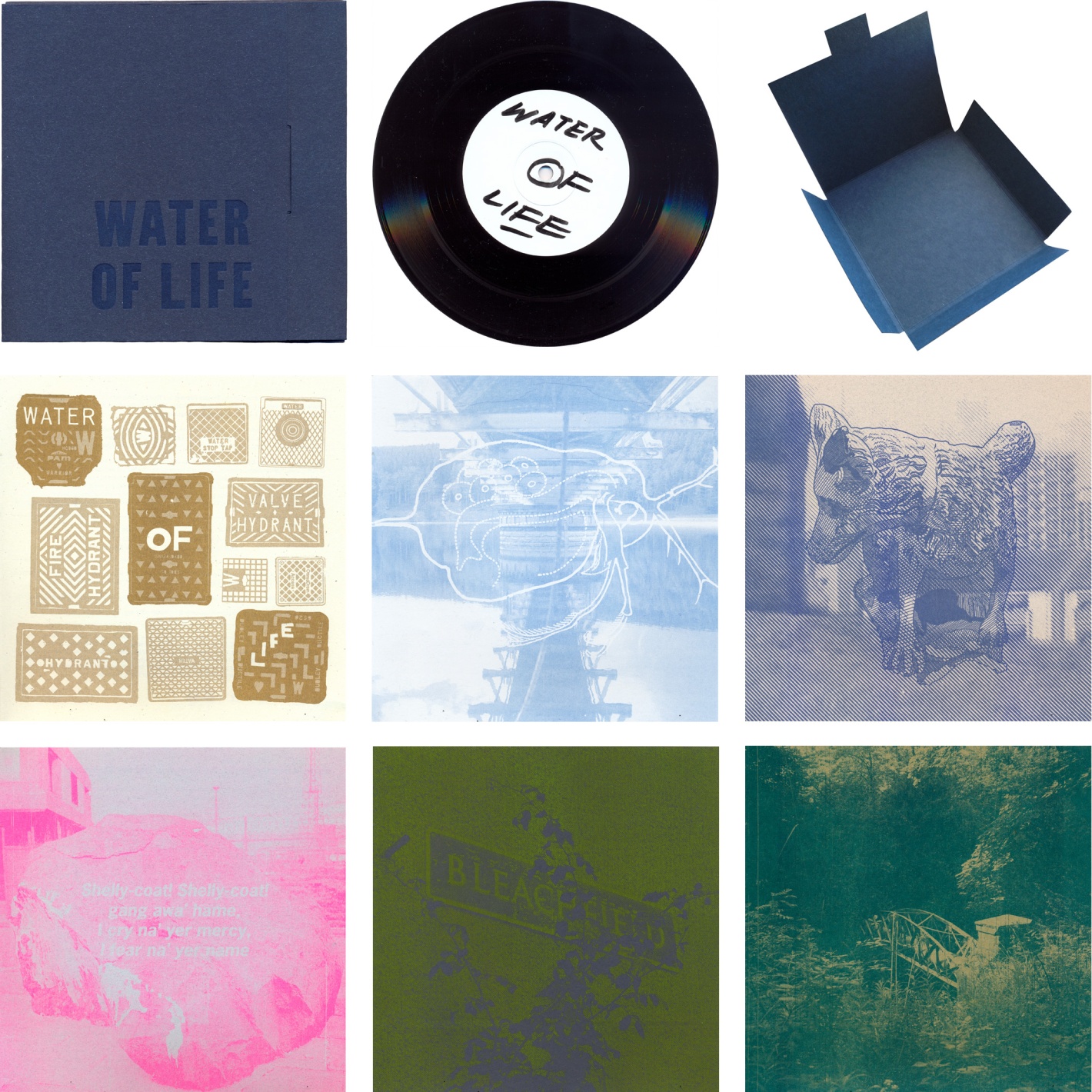

The package comprises: a letterpressed folder on recycled card, a 7" record pressed on recycled vinyl and a set of essays by Rob and prints by Tommy exploring the themes of the project, riso printed using soy inks on recycled paper.

Recordings made with hydrophone, ambient and contact microphone recordings of rivers, spring houses, manhole covers, pub barrel rooms, pipelines and taps are mixed with the peals and drones of 1960s transistor organs, harmoniums, Swedish micro-synths, drum machines and iPads: a blend of the natural and unnatural; modern and antiquated; hi-fi and lo-fi. Drum beats were sampled from underwater recordings, and reverbs created using the convolution reverb technique to recreate the sonic space of different bodies of water.

Many of the sounds collected around Edinburgh and used to make the record are available on a sound map here: www.edinburghwateroflife.org/sound-map/.

"blurs field recordings with folksong, vintage synths and ambient electronica to create something at once natural, unnatural, and in perfect harmony with its source." - The List

"A fascinating and ambitious project that tests the boundaries of what we perceive as music in the environments we live in" - The Vinyl Factory

"aquatic synths burble alongside pulsating geyser beats and hydrophone chronicles, buoying the double helix allure of coursing waters: a becalming surface simplicity that, on closer inspection, reveals an unceasing shape-shift of busying audial information" - Record Collector

A labour of love from Edinburgh based artists Rob St. John and Tommy Perman, ‘Water of Life’ is a paean to the city’s waterways and the flow of water from the Pentlands to the Forth that at times in history has become the city’s industrial power source, drinking water and lifeblood. St. John is known for his psychogeographical bent, including his recent work with archive film artists Screen Bandita (soundtracking a live showing of antique footage of the Western Isles) and Folklore Tapes. He is also an environmental writer and here his evident love and interest in his adopted city’s history is soundtracked in a limited edition 7”.

Found sounds and field recordings of running water introduce ‘’Sources and Springs/Abercrombie 1949’ before St. John’s harmonium maintains an almost kraut rock motirik pulse. The sense of machinery and water systems pulsating and pumping the life blood of the city is tangible. ‘Liquid City/The Shellycoat’ continues the analogue, Kraftwerkian vibe. The Shellycoat is said to be a water spirit that haunts the Pennybap Boulder that sits in nearby Leith and a chorus of voices recount the children’s song about this entity. These tracks, an ‘alternative travelogue’, evoke memories of 1970s Tomorrow’s World style programmes about a brave new world and as such fit into the hauntological universe of acts such as The Advisory Circle and The Eccentronic Research Council. This music really should be sountracking a BFI release of archive footage; indeed both artists recently performed live to such visuals as a part of the ‘Echo of Light/ Water Of Life’ events.

The field recording element adds an additional dimension to this project; the drum sounds are from hydrophonic recordings made under water, the reverb effects deliberately replicating sub surface natural reverb. Sounds from rivers, manhole covers, spring houses, pub barrel rooms, pipelines and taps also permeate this recording bringing life and authenticity to the carefully orchestrated and beautifully descriptive music.

Limited to an edition of 200, the 7” comes with art prints, essays by St John, and a hand, letter pressed folder. Appropriately the single comes on recycled vinyl. Artefacts like this come along rarely and when they do often do not reach the level of thought, care and quality of Water of Life. Take a drink or dive right in. - Grey MalkinWater of Life may be the evolution of field recordings. Presented in an enormously appealing package, the 45 is accompanied by letterpress artwork and a series of essays that address Edinburgh’s water flow. As the first edition of the larger Imagining Natural Scotland project, it makes a wonderful first impression, and an even better second impression as the listener delves into the structure of the recordings and the background of Edinburgh. Is it possible for people around the world to be interested in a Scottish water system? Amazingly, yes. In the same way as a good novel makes one care about characters and settings that one has never visited, Water of Life makes its subject seem so interesting that the music itself seems almost an afterthought.

Take for example the following description: ”Side B is based on confluences through the city: the pipelines, storm drains and sewers leading to sanitation and the sea, ending in a set of voices singing an excavated children’s song about a watery spirit said to haunt the Pennybap boulder by Seafield Sewage Works.” Okay, honestly, who wouldn’t want to hear a short song (4:32) that packs all that in? This project is about so much more than water; it’s about the ways in which water moves, mutates, and is integrated into human lives. It’s not just something that comes from faucets and dwells in lakes. Water occupies our cells, courses through our veins, provides solace to the afflicted and when agitated, breaks through every barrier.

In “Planning for change: the river as a work of art”, St. John reminds his readers of the danger of floodwaters, then asks, “Does our visual and aesthetic sense of an environment enhance or obscure its history?” The essay “Sourcing water: controversy and confluence” traces disputes over the tapping of “natural” sources. ”Common Springs: the moubray, peewit, sandglass and fox” asks questions about “what we choose to restore, and why”. It seems contradictory to say this, in light of the fact that the vinyl is recycled and the ink has been carefully doled out, but this release is an essential physical purchase; the music is appealing without the artwork and essays, but deeper when regarded as one.

In “Planning for change: the river as a work of art”, St. John reminds his readers of the danger of floodwaters, then asks, “Does our visual and aesthetic sense of an environment enhance or obscure its history?” The essay “Sourcing water: controversy and confluence” traces disputes over the tapping of “natural” sources. ”Common Springs: the moubray, peewit, sandglass and fox” asks questions about “what we choose to restore, and why”. It seems contradictory to say this, in light of the fact that the vinyl is recycled and the ink has been carefully doled out, but this release is an essential physical purchase; the music is appealing without the artwork and essays, but deeper when regarded as one.As expected, the purest field recordings are found at the beginning of Side A, as the sounds of three springs are merged with a swiftly developing tune. The unexpected arrives 90 seconds in with the arrival of a 1960s transistor organ. It all sounds groovy and mod, a welcome occurrence in the midst of what we were all taking so seriously. This confluence may echo the confluence of rivers, but it is instead a confluence of disciplines: field recording and music, nature and art, memory and vision, and a huge dollup of happy awareness. The aforementioned “Liquid City/The Shellycoat” finishes with the sound of joyful children. Perhaps we’ve all been too dour about this conservation business. A smile is more effective than a frown, and that’s what Water of Life provides. - Richard Allen

Water Of Life: A Liquid Cartography Of Edinburgh In Sound, Words & Images

Nicola Meighan

Rob St John and Tommy Perman have created Water Of Life, a sound and visual art project devoted to the journey of water from the Scottish hills to and through the city of Edinburgh. Nicola Meighan interviews.

The city of Edinburgh has been re-mapped, thanks to liquid cartographers Tommy Perman and Rob St John. Their Water of Life (ad)venture is a fascinating underground city guide that includes performances, talks, a 7" with art prints and essays, and a ground-breaking water-borne sound-map of Edinburgh.

The endeavour is steeped in local history, geography, industry and mythology, as inspired (and choreographed) by Edinburgh’s water network, and it heralds a high-watermark in the careers of cult-pop artist Perman (ere of ingenious Scottish art-pop collective FOUND) and enthralling doom-folk topographer St John.

You can trace their collaboration back to St John’s Water Lives project (2012) for Oxford University – wherein he produced a collaborative project bringing Perman together with an animator, haiku poet and a group of freshwater biology scientists and academics – but we also have a domestic plumbing riddle to thank for Water of Life: a blocked pipe in St John’s Edinburgh flat, which was owned by Perman, gave rise to their nascent conversations about the beauty, chaos and mystery of water in the city.

The duo tapped water throughout Edinburgh, from mountain reservoirs to Royal Mile manhole covers (one such apparent drain, they discovered, was actually housing a waterfall) and Perman takes us on a journey to one of the key historic sites, now hidden within a housing estate: the graffiti-scrawled, nettle-entangled and partially-derelict 17th century Comiston Springs Water House, which serviced the city until the early 1700s. You can still hear its water burbling, if you put an ear to the iron door, and it provides one of many field-recordings that blurs with folksong and ambient electronica on the Water of Life compositions, some of which are available now as a limited, beautifully-packaged 7".

Each of the tanks in the Comiston Springs Water House was originally protected by a lead animal (fox, swan, lapwing, hare and, according to legend, a now-missing owl). These creatures give the nearby forgotten well heads and residential streets their names – Fox Spring Rise; Swan Spring Avenue – and their mythology (they were thought to represent a conduit between real and imagined realms) permeates St John’s accompanying essays, and Perman’s techno-folkloric visual art.

Comiston Springs Water House distils the essence of Water of Life: it questions perceptions of, and boundaries between, natural and man-made contexts; it demonstrates the inextricable (and harmonious) relationship between nature and industry, science and mythology; it reflects a constant, yet constantly unknowable, source. It gives water a voice.

Did the idea of Water of Life spring from any existing ventures, research or sound-maps?

Robert St John: As far as I’m aware, this is the first time anything like this has been done in Edinburgh. Ian Rawes' work on the excellent London Sound Survey is an ever-present inspiration, and he's put together a sound map of London's waterways. Annea Lockwood's 'Sound Map of the Hudson River' and 'Sound Map of the Danube' were similarly inspiring, as recordings of water carry traces of voices, transport, industry, animals that surround the waterway. The burbles and drones in the recordings can sound like minimal ambient electronica, all the time a rich descriptor of the landscape the water briefly inhabits.

In more general terms, I was excited about using water as a way of tracing new routes through the city, being led to stories and sites that I hadn't encountered before, all with a fair element of chance and uncertainty. I suppose we're inspired by the Situationist movement in some ways, attempting to find new ways of understanding and inhabiting the places we live in: place-making and storytelling.

How did you go about plotting and creating the sound-map, and with what goals? I'm curious about the extent to which it was informed by existing documentation / geography and how much it was shaped by your imagination / aesthetic / mythology.

RSJ: The starting point for plotting the sound-map was to scour an OS map of the city, marking all water (or traces of water) I could find, and these became the first points for fieldwork. The second strand was the archival research I carried out in the National Library of Scotland and City Archives, attempting to trace the histories of water in the city, which often wheeled off into fascinating social and cultural histories – for example, Seafield Sewage Works and The Shellycoat, and the Comiston Water Houses.

The goal was to create a sound palette which represented the different sounds of water in the city: a set of recordings which were kept intentionally brief (30 seconds – two minutes), taken using hydrophones, ambient and contact microphones. The sound-map aims to give a new way of exploring the city, revealing traces of water and the stories attached to them. We've been in contact with the sound archive at the British Library, where the recordings will form part of their UK-wide natural sounds map.

Rob, one of the ideas you touch upon in your essays is that Water of Life allows you to explore the ways that scientists and artists can collaborate to explore and interpret the environment in new ways. Would you agree that the opposite also applies? That tapping the environment's resources allows you to explore and understand music, and art, in new ways too?

RSJ: Water's interesting to think about in the city, as it is always in flux: from polluted to purified; refined and restrained to unruly and flood-making. I'm interested in how we think about conceptions of nature and 'naturalness' in the environment, and in this project, specifically how nature is thought about, used and managed in the city: finding gaps and niches for life to thrive amongst the concrete. This idea of collaboration between scientists and artists appeals to me (not least because I think I fall somewhere in the fuzzy middle between the two disciplines), because of some common guiding principles: a shared curiosity and creativity in understanding and reimagining the world around us.

In the Water Lives animation I produced a couple of years ago for Oxford University, I thought about these ideas a lot: how tiny microscopic lives – the unseen diatoms and algae in water – have beautiful, alien shapes and structures, and how admiring their beauty and learning a little about their biology could perhaps be done in parallel. I think these collaborations are at their most potent when scientists and artists work together from the start on a project in as many ways as possible, rather than artists solely being the translators and communicators of scientific work.

The Water of Life 7" is intrinsically linked to the project – its music and production has water as its primary source; its ambient, liquid electronica channels local aquatic folklore – but it’s also a fascinating artefact (and very fine record) in its own right. Can you please tell me a bit about the intentions and inspiration behind it?

Tommy Penman: We didn't actually know if it was right to make any music right until the end of the project. And then there was no doubt in our minds. There were so many themes and stories for us to respond to that writing the music was dead easy, everything flowed. For example, I wrote a piece of music responding to the Water House at Comiston springs which has a little scene for each of the animals – it seemed right to write a little melody for each – and one of them's not there, the owl, so that melody is kind of sparse. - thequietus.com/

Let us be thankful for Rob St John’s plumbing woes. Were it not for a pipe-drain drama at the alt-folk topographer’s Edinburgh flat, and a subsequent chat with his landlord – better known as art-pop whiz Tommy Perman – we may not have their collaboration, Water of Life.

Inspired by Edinburgh’s water network and funded by Creative Scotland’s Year of Natural Scotland, it’s an enthralling underground guide to the city that includes performances and talks, a seven-inch with prints and essays, and a groundbreaking water-borne sound-map of Edinburgh, which will contribute to the British Library’s UK-wide natural archive.

Their city-wide liquid cartography was informed by geography and mythology. “The starting point was to scour an OS map, marking all the water I could find,” says St John. “These became the first points for fieldwork. The second strand was the research I carried out in the National Library of Scotland and City Archives, attempting to trace the histories of water in the city, which often wheeled off into fascinating social and cultural histories.”

Perman, formerly of art collective and tech-rock troupe FOUND, takes us on a leafy city-centre voyage to a vital site: the nettle-entangled and partially-derelict 17th century Comiston springs water house, which serviced the city until the early 1700s. You can still hear the water burbling, if you put an ear to the iron door, and it’s one of many field-recordings that blurs with folksong and ambient electronica on the Water of Life compositions.

The tanks in the water house were originally watched over by lead animals (fox, swan, lapwing, hare and, according to legend, a now-missing owl), who give the nearby forgotten well heads and residential streets their names, and whose mythology (they were thought to represent a conduit between real and imagined realms) permeates St John’s accompanying essays, and Perman’s visual art.

The area distils the essence of Water of Life: it questions perceptions of, and boundaries between, natural and man-made contexts; it demonstrates the inextricable (and harmonious) relationship between nature and industry, science and folklore; it reflects a constant, yet constantly unknowable, source. It gives water a voice.

Did the pair’s collected found-sounds from Comiston springs, and neighbouring reservoirs, lochs and bathtubs, steer the project’s musical narrative? “I wouldn’t say that they directly informed the chords and musical motifs we wrote,” Perman offers. “I think the stories and their themes informed that more. For example, I wrote a piece of music responding to Comiston springs, which has a little melody for each of the animals – and one of them, the owl, isn’t there, so the music for that’s kind of sparse.”

St John agrees. “The first track on the single, Harperigg / Abercrombie, 1949, takes a set of recordings close to the source of the Water of Leith, and leads into an organ melody inspired by Basil Kirchin and post-war plans for the city’s environment. The second is based on the idea of water constantly being reworked, blended and channelled away under our feet in pipelines and, finally, the sewage works,” he says. “We ended it with a snatch of a tune about The Shellycoat, a watery spirit which is said to haunt a boulder, The Pennybap, which was previously off the shore at Seafield, and now sits in the car-park of some office buildings next to the sewage works.

“The tracks were created using recordings from the sound-map as drones, texture and percussion, like dripping taps and stones moving underwater, alongside a limited set of instruments – transistor organ, harmonium, synth and iPad,” St John continues. “We wanted to reflect the hybrid nature of water in the city: constantly in flux, a blend of the environmental and social; technological and folkloric.”

Perman nods: “We wanted to tell the story of a landscape and human interaction with it, and their impact on it, so it made sense for us to edit and respond to the sounds, not just have unadulterated field recordings. It felt like we were doing what we were seeing around us. Everything fed into everything else.”

And it does. Water of Life underscores the significance of water at every level, and indeed the importance of art: it re-maps our physical and imagined landscapes; it changes our perceptions of our day-to-day surroundings; it makes us reassess the world(s) around us, and beneath our feet.

This article originally ran in The Herald Newspaper (Scotland) on November 6, 2013.

- nicolameighan.wordpress.com/

Water of Life: Interview with Rob St John and Tommy Perman

Water of Life: Interview with Rob St John and Tommy Perman

Water of Life is an art-science collaboration between Rob St. John and Tommy Perman exploring flows of water through Edinburgh using drawings, photos, writing and sound.

I was suitably intrigued when I found out that Rob and Tommy were teaming up for the project. They are both multi-talented artists who have contributed a lot to the music and art scenes in Edinburgh and beyond.

Rob makes music under his own name and as part of eagleowl, as well as writing for the likes of Caught By the River. Tommy was up until recently a member of band and art collective FOUND, produces art/illustration as Surface Pressure and recently released an EP under the name ComputerScheisse.

I hope that introduction has whet your appetite. Now, here are a few probing questions about the project’s creative flow.

How did the Water of Life project come about in the first place and what were the main aims of the project?

Rob: Tommy and I had worked on a few things together before, and had found that we had shared interests: the overlaps between art and science; finding new ways of exploring, seeing and thinking about the city.

Creative Scotland’s ‘Imagining Natural Scotland’ fund was announced in the Spring, and we put the project together in response to the call: thinking about what we term ‘natural’ in the Scottish (and wider) landscape, and how this ‘naturalness’ has been imagined and reshaped, both literally and metaphorically through time.

Tommy: I’d previously worked with Rob on a handful of different music and art projects. I had been a huge fan of Rob’s music and at one point his live band were my favourite act in Edinburgh (they only lost that esteemed position as Rob moved away to Oxford).

We definitely share a bunch of interests across art, design, music, photography and science. Rob spotted the opportunity and suggested we put in a proposal. We met up a few times, chatted and the idea for Water of Life emerged pretty quickly.

Did you both share a fascination for Edinburgh’s watery past? Why did you choose to explore this topic in particular?

Rob: Water was a great focal point for exploring the city, in the way that it was been constantly reshaped and managed through history: streams culverted off underground into sewers; lochs drained and refilled; the water itself constantly changing, from filtered to polluted; connecting our selves with pipelines through our houses, the water in rivers, lochs, sewers, drains, sanitation plants.

As well as asking questions about what we term ‘natural’ or ‘wild’ in the city, traces of water often reveal interesting conduits into Edinburgh’s past. Street names often echo watery histories. In Edinburgh this includes: historic water supplies (Fox Spring Avenue and Swan Spring Avenue are both named after springs at Comiston that first fed the city in the 17th century); lost lochs (Boroughloch at the edge of the former loch on the Meadows) and industry along the Water of Leith (Tanfield, Bleachfield, Ladehead).

Tommy: For a while before we began this project I’d been interested in the Edinburgh sewage works down at Seafield. For those who know my visual artwork, I’m very interested in the less well documented details of city life. I had become fascinated by Seafield because visually it looks completely different from anywhere else in Edinburgh. There’s some wonderful, industrial buildings and large scale pipe work visible from the perimeter fence.

I’d also been looking at satellite images of Seafield on Google Earth and loved the repeating circles of the water treatment pools. So when we embarked on this collaboration I was already thinking about the kind of life support systems a city needs to sustain its inhabitants and I think we both took that as a starting point and followed it in different directions.

How did the collaborative process work? Did you agree on specific roles?

Rob: We worked as collaboratively as possible, taking off on field trips across Edinburgh’s water network, from the grand Talla and Megget reservoirs in the Borders, which together provide much of the city’s drinking water, to the Seafield Sewage Works, where much of the city’s water ends up, sullied and full of dissolved excess. The trips would be exploratory, taking in sound recordings, photography and note making.

For example, we went to the Glencorse reservoir in the Pentlands, interested in the new sanitation plant, and the 19th century reservoir. Denied access to both (a common theme in the project, raising other questions), we happened upon the old filter beds below the reservoir – now overgrown, with the remnants of the industrial process now mingling with encroaching nature, giving the impression of a landscape art installation.

Tommy: I think we were aware of each others strengths so there were certain tasks that we divided up. Rob is very good at researching a subject and spent a lot of time in various libraries across Edinburgh uncovering amazing stories that I definitely wouldn’t have found on my own. Rob also did the bulk of the writing as it’s a skill that comes easy to him. I like writing but it tends to tax my brain a lot – especially since becoming a dad early this year – I find it very difficult to focus long enough to get the words down.

I took charge of researching how we were going to produce and manufacture the records, folder and prints. And I did most of the design and drawings. But even in these areas we collaborated – making suggestions and offering each other our opinions.

Did anything unexpected come out of the collaborative process or the research?

Rob: We set off with an exploratory remit: to work collaboratively, drawing from elements of artistic and scientific practice; to attempt to trace ideas of what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ regarding water in the urban environment. As a result, most of the stories we discovered were new and unexpected, and we ourselves found new ways of seeing and understanding a city we’d both lived in for a considerable amount of time.

For example, in the car park of office buildings by the Seafield Sewage Works sits a glacial erratic boulder, the Pennybap. This boulder is said to be inhabited by a Shellycoat, a water-based spirit, yet is neglected and off-limits, a blend of the folkloric, historical and industrial, perhaps a good metaphor for how we view and use water in the city.

Tommy: Although we submitted a detailed funding proposal with fairly concrete outcomes, I had no idea what the content of our project would be. I really enjoyed allowing our research and the materials we gathered on field trips to inform the artwork we produced at the end of the project.

I didn’t expect us to write so much music – in fact at the beginning of the project we weren’t sure if the audio component would be just field recordings or something else. I also hadn’t anticipated that we’d use film photography and that the results of the photos we took would be so unusual (my pictures came back from the developers marked with random vertical streaks which at first disappointed me but then I realised totally added to the images).

A few things that stand out to me from perusing the website are the attention to detail that has gone into both the research and the artwork, including the packaging etc. Would it be fair to say that this is an integral part of both of your approaches to your creative work, and could you both say a little bit about why that’s important to you?

Rob: Yes, it’s an important part of how we both work, I think. From my perspective, it’s important that every bit of creative output has a number of tangents that you can follow out: links, histories, sites. We’ve created the release of a 7″, prints and essays in a letterpressed folder. All aspects of the production process have been chosen to minimise their environmental impact: the vinyl, paper and card used is recycled, the essays and prints printed with soy inks, and the letterpress with existing type and a teaspoon of ink for 300 copies.

Part of the motivation for this process was to try and show that it is possible and (reasonably) affordable to incorporate ideas of environmental impact into your production process for projects such as ours, which can hopefully be used as inspiration for others wanting to do similar things.

Tommy: I’m very happy that you’ve noticed this! I think my parents would tell you that I’ve always been interested in fine details ever since I started drawing as a young child. But in recent years I have wondered if it’s really necessary to put quite as much detail into each project. I know you’re aware of my previous collaborations with FOUND, in our last project #UNRAVEL we produced 160 pieces of music for the installation. My collaborator Simon pointed out that it’s very possible that a number of these songs will never be heard. I felt a bit crestfallen when he mentioned this.

It’s clear I really enjoy the process of creating artwork but my intention (and hope) is that there will be an audience for it. Working with Rob was potentially quite dangerous for producing work with such depth of detail that some might be lost. We both have this tendency to really think the details through to a ridiculous degree. When I was working on the audio production for the music I kept asking myself if I could justify the choices I was making within the limits of the project. I desperately wanted every element to feel like it belonged.

The project was funded by Creative Scotland – presumably without that funding it wouldn’t exist at all? Do you have any advice for other artists who want to pursue funding for their projects?

Rob: We’re grateful to the ‘Imagining Natural Scotland‘ fund for making this work possible. Tommy and I would have most likely collaborated anyway, but the funding allowed us both to experiment and to address every aspect of the project as we wanted: from research to manufacture, allowing us time for reflection and the ability to address environmental impact in every aspect of the production process.

Tommy: It is amazing to have a budget to work on a project like this and produce a 7″ vinyl with some pretty lavish packaging. These kinds of opportunities don’t arise very often so when they do I think it’s best to make the most of them. I think we have and I’m convinced we got a lot for our budget. - www.clearmindedcreative.com/

I was suitably intrigued when I found out that Rob and Tommy were teaming up for the project. They are both multi-talented artists who have contributed a lot to the music and art scenes in Edinburgh and beyond.

Rob makes music under his own name and as part of eagleowl, as well as writing for the likes of Caught By the River. Tommy was up until recently a member of band and art collective FOUND, produces art/illustration as Surface Pressure and recently released an EP under the name ComputerScheisse.

I hope that introduction has whet your appetite. Now, here are a few probing questions about the project’s creative flow.

How did the Water of Life project come about in the first place and what were the main aims of the project?

Rob: Tommy and I had worked on a few things together before, and had found that we had shared interests: the overlaps between art and science; finding new ways of exploring, seeing and thinking about the city.

Creative Scotland’s ‘Imagining Natural Scotland’ fund was announced in the Spring, and we put the project together in response to the call: thinking about what we term ‘natural’ in the Scottish (and wider) landscape, and how this ‘naturalness’ has been imagined and reshaped, both literally and metaphorically through time.

Tommy: I’d previously worked with Rob on a handful of different music and art projects. I had been a huge fan of Rob’s music and at one point his live band were my favourite act in Edinburgh (they only lost that esteemed position as Rob moved away to Oxford).

We definitely share a bunch of interests across art, design, music, photography and science. Rob spotted the opportunity and suggested we put in a proposal. We met up a few times, chatted and the idea for Water of Life emerged pretty quickly.

Did you both share a fascination for Edinburgh’s watery past? Why did you choose to explore this topic in particular?

Rob: Water was a great focal point for exploring the city, in the way that it was been constantly reshaped and managed through history: streams culverted off underground into sewers; lochs drained and refilled; the water itself constantly changing, from filtered to polluted; connecting our selves with pipelines through our houses, the water in rivers, lochs, sewers, drains, sanitation plants.

As well as asking questions about what we term ‘natural’ or ‘wild’ in the city, traces of water often reveal interesting conduits into Edinburgh’s past. Street names often echo watery histories. In Edinburgh this includes: historic water supplies (Fox Spring Avenue and Swan Spring Avenue are both named after springs at Comiston that first fed the city in the 17th century); lost lochs (Boroughloch at the edge of the former loch on the Meadows) and industry along the Water of Leith (Tanfield, Bleachfield, Ladehead).

Tommy: For a while before we began this project I’d been interested in the Edinburgh sewage works down at Seafield. For those who know my visual artwork, I’m very interested in the less well documented details of city life. I had become fascinated by Seafield because visually it looks completely different from anywhere else in Edinburgh. There’s some wonderful, industrial buildings and large scale pipe work visible from the perimeter fence.

I’d also been looking at satellite images of Seafield on Google Earth and loved the repeating circles of the water treatment pools. So when we embarked on this collaboration I was already thinking about the kind of life support systems a city needs to sustain its inhabitants and I think we both took that as a starting point and followed it in different directions.

How did the collaborative process work? Did you agree on specific roles?

Rob: We worked as collaboratively as possible, taking off on field trips across Edinburgh’s water network, from the grand Talla and Megget reservoirs in the Borders, which together provide much of the city’s drinking water, to the Seafield Sewage Works, where much of the city’s water ends up, sullied and full of dissolved excess. The trips would be exploratory, taking in sound recordings, photography and note making.

For example, we went to the Glencorse reservoir in the Pentlands, interested in the new sanitation plant, and the 19th century reservoir. Denied access to both (a common theme in the project, raising other questions), we happened upon the old filter beds below the reservoir – now overgrown, with the remnants of the industrial process now mingling with encroaching nature, giving the impression of a landscape art installation.

Tommy: I think we were aware of each others strengths so there were certain tasks that we divided up. Rob is very good at researching a subject and spent a lot of time in various libraries across Edinburgh uncovering amazing stories that I definitely wouldn’t have found on my own. Rob also did the bulk of the writing as it’s a skill that comes easy to him. I like writing but it tends to tax my brain a lot – especially since becoming a dad early this year – I find it very difficult to focus long enough to get the words down.

I took charge of researching how we were going to produce and manufacture the records, folder and prints. And I did most of the design and drawings. But even in these areas we collaborated – making suggestions and offering each other our opinions.

Did anything unexpected come out of the collaborative process or the research?

Rob: We set off with an exploratory remit: to work collaboratively, drawing from elements of artistic and scientific practice; to attempt to trace ideas of what is ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ regarding water in the urban environment. As a result, most of the stories we discovered were new and unexpected, and we ourselves found new ways of seeing and understanding a city we’d both lived in for a considerable amount of time.

For example, in the car park of office buildings by the Seafield Sewage Works sits a glacial erratic boulder, the Pennybap. This boulder is said to be inhabited by a Shellycoat, a water-based spirit, yet is neglected and off-limits, a blend of the folkloric, historical and industrial, perhaps a good metaphor for how we view and use water in the city.

Tommy: Although we submitted a detailed funding proposal with fairly concrete outcomes, I had no idea what the content of our project would be. I really enjoyed allowing our research and the materials we gathered on field trips to inform the artwork we produced at the end of the project.

I didn’t expect us to write so much music – in fact at the beginning of the project we weren’t sure if the audio component would be just field recordings or something else. I also hadn’t anticipated that we’d use film photography and that the results of the photos we took would be so unusual (my pictures came back from the developers marked with random vertical streaks which at first disappointed me but then I realised totally added to the images).

A few things that stand out to me from perusing the website are the attention to detail that has gone into both the research and the artwork, including the packaging etc. Would it be fair to say that this is an integral part of both of your approaches to your creative work, and could you both say a little bit about why that’s important to you?

Rob: Yes, it’s an important part of how we both work, I think. From my perspective, it’s important that every bit of creative output has a number of tangents that you can follow out: links, histories, sites. We’ve created the release of a 7″, prints and essays in a letterpressed folder. All aspects of the production process have been chosen to minimise their environmental impact: the vinyl, paper and card used is recycled, the essays and prints printed with soy inks, and the letterpress with existing type and a teaspoon of ink for 300 copies.

Part of the motivation for this process was to try and show that it is possible and (reasonably) affordable to incorporate ideas of environmental impact into your production process for projects such as ours, which can hopefully be used as inspiration for others wanting to do similar things.

Tommy: I’m very happy that you’ve noticed this! I think my parents would tell you that I’ve always been interested in fine details ever since I started drawing as a young child. But in recent years I have wondered if it’s really necessary to put quite as much detail into each project. I know you’re aware of my previous collaborations with FOUND, in our last project #UNRAVEL we produced 160 pieces of music for the installation. My collaborator Simon pointed out that it’s very possible that a number of these songs will never be heard. I felt a bit crestfallen when he mentioned this.

It’s clear I really enjoy the process of creating artwork but my intention (and hope) is that there will be an audience for it. Working with Rob was potentially quite dangerous for producing work with such depth of detail that some might be lost. We both have this tendency to really think the details through to a ridiculous degree. When I was working on the audio production for the music I kept asking myself if I could justify the choices I was making within the limits of the project. I desperately wanted every element to feel like it belonged.

The project was funded by Creative Scotland – presumably without that funding it wouldn’t exist at all? Do you have any advice for other artists who want to pursue funding for their projects?

Rob: We’re grateful to the ‘Imagining Natural Scotland‘ fund for making this work possible. Tommy and I would have most likely collaborated anyway, but the funding allowed us both to experiment and to address every aspect of the project as we wanted: from research to manufacture, allowing us time for reflection and the ability to address environmental impact in every aspect of the production process.

Tommy: It is amazing to have a budget to work on a project like this and produce a 7″ vinyl with some pretty lavish packaging. These kinds of opportunities don’t arise very often so when they do I think it’s best to make the most of them. I think we have and I’m convinced we got a lot for our budget. - www.clearmindedcreative.com/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar