Češko nadrealno proljeće.

Psihodelična prerada priče o Adamu i Evi, performansi antisocijalnih djevojaka, pobuna tehničkih trikova.

Vera Chytilova’s Daisies (1966) manages to be both visceral and abstract, playful and savage, intellectual and infantile, all at once. Watching it last night, I was literally trembling with joy and exhilaration. I felt the same way when I first saw the film, nearly thirty years ago. in graduate school.

Daisies is a film of the Czech New Wave, but it doesn’t have much in common — aside from the rejection of traditional narrative, and of the aesthetics of “socialist realism” — with the other works of the movement. Chytilova, you might say, plays Godard to Jiri Menzel‘s Truffaut. (Chytilova and Menzel went to FAMU, the famed Czech film school together, become close friends, and occasionally worked together — see the biography of Chytilova here). Daisies is a riot of color, jump cuts and shock cuts and deliberate mismatches, garish pictorial inserts, incongruous nondiegetic music and sounds, and anti-naturalistic special effects. Sometimes the screen is in color, sometimes in black and white, sometimes tinted with monochromat filters, and sometimes awash in crazed pixelation (? — or whatever the pre-digital equivalent of this might be) effects. The film as a whole is a relentless assault — against film conventions and forms and indeed cinema itself, against social norms and rules and indeed society itself, and finally against the spectator. This assault is violently nihilistic, but it is also utterly joyous and gleeful: an explosion of affect, in which I share as I watch.

Daisies delights as well as shocks — probably, at this point, delights more than it shocks, if I can judge from the responses of my students viewing it last night. And yet, despite a certain degree of cult devotion, it hasn’t ever been given its rightful due in histories of film, or even in histories of experimental, radical, and avant-garde film. Owen Hatherley writes brilliantly about it (and I am deeply indebted to his analysis of the film); but his is the only discussion I have been able to find that is in any way adequate to the film’s astonishing force and radicality. Even those of us who love Daisies have trouble finding the proper terms to account for it.

Back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in the wake of Laura Mulvey’s groundbreaking article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), there was a lot of debate on the subject of what it might mean to break away from conventional cinematic pleasures. Such pleasures, as Mulvey compellingly demonstrated, are embedded in structures of heterosexual male domination and female subordination. Mulvey herself calls (somewhat ambiguously) for an effort “to free the look of the camera into its materiality in time and space and the look of the audience into dialectics, passionate detachment.” But the main thrust of her essay was upon the “destruction of pleasure.” Mulvey called for a practice (both of criticism and of alternative filmmaking) that “destroys the satisfaction, pleasure and privilege” of conventional film viewing.

Much of the debate, after Mulvey, was over the question of whether feminist filmmaking would therefore have to be didactic, “alienating,” and intellectualizing; or whether other regimes of pleasure and affect, besides the patriarchal one, were attainable (or even conceivable). Did anyone notice that, a decade before Mulvey, Chytilova had already answered this question, in the affirmative? For the sheer joy of Daisies owes nothing to the mechanisms of identification and objectification, sadism and paranoia, that Mulvey dissects in her article. Daisies works, it works very powerfully indeed; but we don’t have a good language to describe how and why it works, and that is a large part of the reason it has been relegated to the margins of film history.

So, we have two girls — or young women, if you prefer; the actresses (Jitka Cerhova and Ivana Karbanova) are probably in their early twenties. (The IMDB doesn’t list their dates of birth, and says that neither of them ever acted in films again, aside from a couple of minor roles just after Daisies, in 1966 and 1967). We don’t even know these characters’ names — indeed, they are both called by a number of different names over the course of the film — though most discussions, and the credits list on IMDB, call them “Marie I” and “Marie II.”

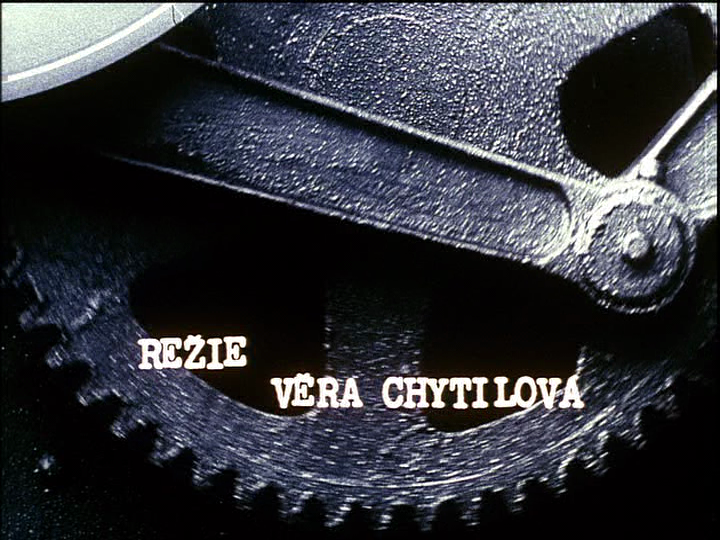

After the opening credits — which are printed against a montage combining, on the one hand, shots of something that looks like a 1920s Constructivist or Dadaist machine-sculpture, and on the other hand, grainy video footage of wartime bombings and destruction — we see the two Maries seated, side by side and facing the camera, in some sort of open box or proscenium stage. Their bodies are stiff, their movements are awkward, as if they were puppets. Every time either of them moves a limb, we hear a loud creaking on the soundtrack, suggesting a kind of clumsy mechanical animation. They are bored. They tell each other that, because the world is “bad,” their only alternative is to be “bad” too. (Another translation has “spoiled” instead of “bad”).

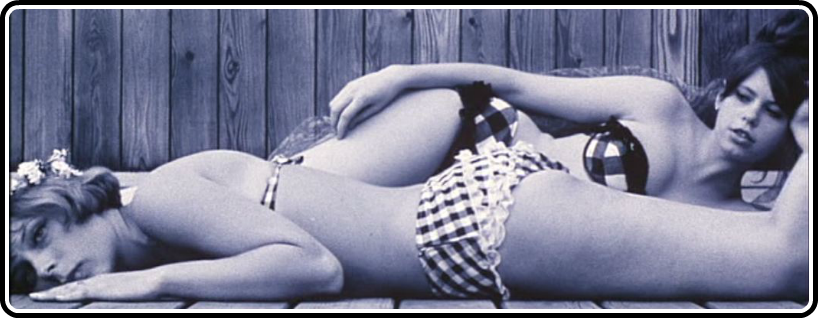

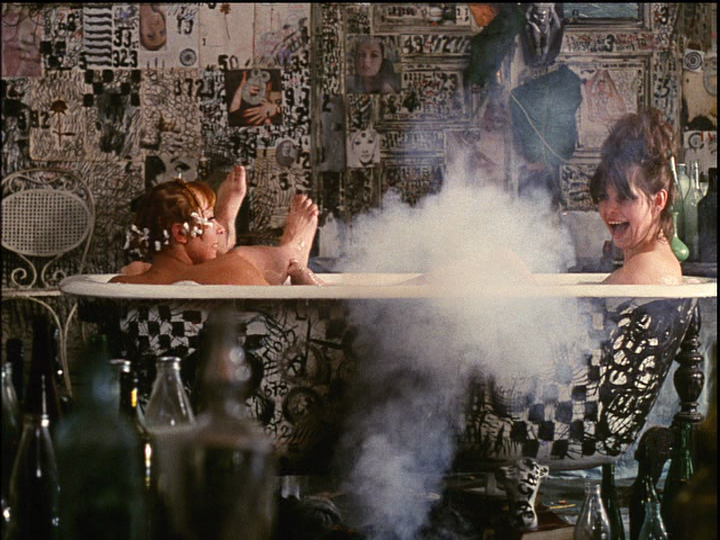

The two Maries go on to indulge themselves in various sorts of antisocial behavior. They continually complain to one another, and squabble. But they don’t seem to have any stake in these arguments, and it’s impossible to make any consistent distinction between their points of view. (One is blonde and one brunette, and that’s as far as their differences go). They go out on dates to fancy restaurants with evidently well-to-do older men (what does this mean in the Communist context? We know that socialist society wasn’t as classless and egalitarian, nor as gender-equal, as it was supposed to be). The men buy them expensive drinks and food, hoping (presumably) to seduce them, but instead finding themselves having to cope with the girls’ raucous behavior. Marie and Marie wear short dresses; one of them wears her hair is in ponytails; both of them put on lots of eyeshadow. They seem less like vamps than like little girls playing dress-up, or (more disagreeably) like objects of pederastic fantasy (do I have the right word here? what is the heterosexual equivalent of “pederastic”?). The men never get the sex they were hoping for; instead they are hustled off to catch a train, and abandoned. The girls just laugh giddily, and go off to make more trouble.

The two Maries gleefully trash their own apartment, as well as all the public spaces they wander through; they are constantly on the move, from the latrine of some lavish restaurant, to the banks of the river, to the train station, and finally through the corridors and up the floors (riding in a dumbwaiter) of an imposing official building, where they find food and silverware lavishly and meticulously laid out for (we presume) some sort of State banquet. In the climactic sequence of the film, they proceed to trash the banquet room, stuffing themselves with giant portions of meat and poultry, devouring cake and booze, smashing plates and glasses, having tumultuous food fights, and finally swinging from the ceiling chandelier. Meantime, the soundtrack music is either portentous or martial, taken from Wagner’s Ring among other sources. Surely this is the greatest “food” sequence in the history of film.

A word of distinction is in order. The two Maries’ bad behavior isn’t anything like the girls-can-act-like-raunchy-frat-boys-too stuff we’ve seen so much of in recent years, whether in TV shows like Sex and the City, or in fashionable public behavior like that analyzed in Ariel Levy’s recent book Female Chauvinist Pigs. These are situations in which women displace men in order to take over the dominating phallic role for themselves — and end up, therefore, behaving just as stupidly and oppressively as men do.

But the two Maries’ behavior works in an entirely different register. It is completely infantile. They seem uninterested in sexuality per se: they only dress up in swinging-sixties-”sexy” garb the better to confound and humiliate older men (something they are interested in) and to create general confusion and disorder. Instead of sex, they are interested in food. They lose no opportunity to gorge themselves. And they take a child’s pleasure in breaking stuff, shredding stuff, and burning stuff. In particular, they are continually cutting things up with scissors. This latter action resonates with “cutting” in the cinematic sense; their aggression is matched by Chytilova’s anti-continuity editing, which often cuts correctly on action or on an object, only in order to place everything abruptly into a totally different setting. In one sequence, the Maries cut up parts of their own bodies on screen — one’s arm suddenly disappears, followed by the other’s head; finally the screen image itself gets cut, breaking up into small squares squirming all over the frame.

In Freudian terms, one might say that sexuality has been repressed in favor of a regression to oral — narcissistic, incorporating, and aggressive — drives and pleasures. But I think the Maries’ behavior is better seen affirmatively, as a positive construction, rather than as a reaction or regression. The movement from sexuality to food is, precisely, a detournement in the Situationist sense, rather than a “failure of development.” It is also a Rimbaudian “systematic derangement of the senses,” and a Nietzschean movement, a striving “to realize in oneself the eternal joy of becoming — that joy which also encompasses joy in destruction.” Though certainly Nietzsche never imagined this happening in so delightfully “girlie” a manner as it does here.

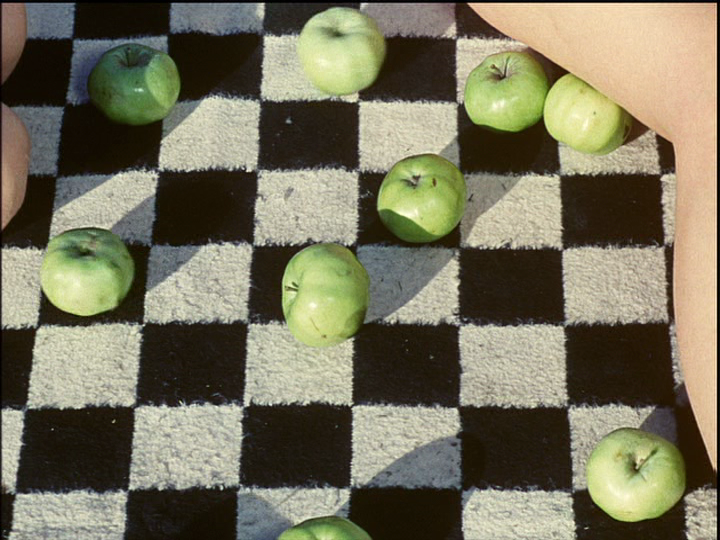

The two Maries’ delight in gorging themselves on food and drink is intimately connected with their delight in cutting. Their play with scissors evidently implies castration. Besides newspapers, bedspreads, and their own and others’ clothing, they are also continually snipping up phallic objects like sausages and pickles — as well as presumptively feminine ones like apples. (Castration, figurative or literal, seems to be a recurring theme in Chytilova’s work. One of her far more recent films, Traps (1998), which unfortunately I have never had the opportunity to see, aroused much controversy for its story of a woman who castrates the two men who raped her).

Destroying the phallus doesn’t just mean undermining male power, but undermining the power of the whole “Symbolic Order.” Among othet things, it means destroying the opposition — or undermining the gap — between things and words, or more broadly between things and their representations (whether these be verbal or visual). At one point, one of the Maries cuts out a picture of food from a magazine, then stuffs it into her mouth and chews it up with the same avidity she shows for actual food. This is in the course of a scene where the two Maries roast sausages by setting fires and burning down parts of their apartment. Then they spear and cut the wieners with an enormous cook’s fork, and an equally enormous pair of scissors. All the while they laugh at the complaints of a jilted lover, whose pathetic pleadings are heard over the phone. During the entire scene, some sort of sacramental choral music plays, nondiegetically, in the background.

Everything the two Maries do is destructive. They revel in sheer waste, in “unemployed negativity,” in “expenditure without return.” Above all, Daisies expresses utter scorn for any sort of productivity, whether economic, social, or semiotic This, of course, is a major reason why the film was denounced by Party authorities for wasting the resources of the State, and insulting “the working people in factories, in fields, and on construction sites.” As production was the highest value in all the socialist states, the general derision which Daisies pours on the very concept is actually more disturbing to official ideology than a more explicit, specific, and immediate criticism of the social system would have been.

There is one sequence in Daisies in which the two Maries watch a farmer watering his crops. He doesn’t notice them, despite their outlandish attire. They then stand in a square they are passed by a squad of bicyclists, probably workers going off to their work in a factory. Once again, nobody notices them. They start to wonder whether they even exist: obviously, there is no place for them in the world of “actually existing socialism.”

(It’s dubious whether they could exist in “actually existing capitalism” either. Their orgies of expenditure might be seen as a sort of consumerist excess, except that they never pay for anything. They steal money, but they never spend it. They have no regard for, and no sense of, property; no sense of material goods as a source of power or prestige. Their infantilism, unlike that of the capitalist consumer, unegotistical. They have no interest in possession and accumulation).

After the Maries destroy the State banquet, the film ends with their display of remorse, and punishment for their bad behavior. This formulaic recantation is done so sarcastically that it only further accentuates the film’s overall childish glee in pure waste and destruction. (Is it worth noting that, after the Soviet invasion of 1968, Chytilova and other Czech New Wave directors were similarly forced to make critiques and recantations of their work?) The Maries mumble their sorrow, and say that now they are happy to be socially useful, as they ostensibly put everything back in order: this involves putting the shards of broken plates back next to each other, and throwing handfuls of crumbs back together on large platters. Finally they lie down on the top of the banquet table, wearing body suits made of newspaper and papier mache, murmuring that they are finally at peace… until the room’s enormous chandelier falls from the ceiling and crushes them in a final swoosh of multicolored pixelation. Though Chytilova claimed, under political duress, that this was a moral punishment for the girls’ transgressions, it seems rather to extend their reign of destruction, consuming not only the two of them, but the film itself.

What’s great about Daisies is that, even as it revels in negativity and destruction, and even as its protagonists are motivated (to the extent that such language can be used in a film like this at all) by a kind of malaise, there is no sense of lack or incompletion here, no alienated subjectivity, no Lacanian not-all, no Mulveyesque dialectics and detachment, and even no Adornoesque revelation of the work’s own insufficiency — but only a joyous plenitude, an overabundance that is both affective and material, embodied in the sheer exuberance and formal inventiveness of the film itself.

The early modernist endeavor to align radical aesthetics with radical politics came to grief over the horrors of Stalinism, not to mention the ultra-conservative aesthetics of “socialist realism” that Stalin imposed. In post-War, post-Stalin, Communist Eastern Europe, Dusan Makavejev is nearly alone in endeavoring to renew the link between radical aesthetics and radical politics. Chytilova’s late modernist radical aesthetics doesn’t share any such project. It is explicitly, not just apolitical, but virulently antipolitical. Rather than simply affirming the rights of the individual against the collective — a move which would still be “political” in the conventional sense — Daisies obliterates both individual and collective in its fervidly antisocial jouissance. (The two Maries cannot exist without one another; their duality is as irreducible to any sort of heroic or existential solitude and individuality, as it is to any sort of social bond or collectivity). And this antipolitical virulence is precisely the film’s (crucial) political import: one that perhaps we need today, in our “connected” world of inescapable networks and ubiquitous commodification, as much as it was needed 40-odd years ago in the world of “actually existing socialism.”

What would a history of film, or of modernism, or of the avant-garde, or an account of strategies of resistance and evasion and refusal, that took proper and full account of Daisies look like? - Steven Shaviro

Daisies both begins and ends with images of war. These are images of modern warfare, of mass destruction. These sequences frame the rest of the movie, they act like a bracketing device and therefore imply that it is from within them that the rest of the film must be seen and understood. The first scene that introduces the girls portrays them as dolls, their arms squeaking like hinges as they move erratically. This is immediately on the heels of the films opening sequence of war images alternated with close ups of a machine cranking away. Like a doll, a machine does not have a mind of its own to decide its own actions, other people must control and direct it. However unlike a doll a machine can be turned on and left to proceed in its automatic insistence indefinitely. Machines are expendable. When people begin to act like machines, and when people begin to be treated like machines, expected to automatically and blindly follow commands and orders the Dadaists called it automatism. Humans become like machines, expendable, or so they begin to be seen as such. World War I presented the world with destruction and murder on a more massive scale than could have ever been imagined previously. Automatism is the behavior of, and treatment of men like machines, they become part of the greater war machine and are expected to follow orders and kill without question. Likewise, casualties no longer matter, for like machines, men are seen as expendable. When a machine breaks, one replaces it. Dada was a response in the arts to the horrors of World War I.

Immediately following the images of war, and portrayed as dolls, the girls’ first conversation of the film is their most expansive. They decide and agree that “the world has gone bad.” Throughout the rest of the film the girls’ excuse and justification for acting the way they do is the, by now determined fact, that the world has gone bad and has therefore caused them too to go bad. That all the world has gone bad seems to be inextricably linked with the film’s opening images of war and allusion to both Dada and automatism. The film seems to imply that war has inspired a world wide sensation of numbness, people have been left semi-comatose – automatically and blindly doing only what is expected of them, like machines or dolls. The horrors of such massive and murderously destructive war have rendered everything meaningless. There no longer exists the optimistic hope of a grand narrative or salvation. As was an aim of Dada art, Daisies also seems to imply that all is meaningless. In these ways Daisies seems decidedly post modern. Post modern in its reliance on figurative form, on its anti-narrative aim and in its assurance that the horrors of the world have rendered human action meaningless. In Daisies the girls must first realize this reality, the reality that there is no truth or any such thing as the hopefulness of a greater, more important overriding narrative, some shred of justice or slither of meaning. Once, in their first scene, the girls have realized this they can finally act out as they have been dying to. No longer imbedded in the false security of social routine and norm, they can finally be free to do whatever they want. However, their destructiveness and the negativity that they inspire is by no means implied to be the necessary human condition. Rather, it is the necessary response to all the mass destructiveness and negativity that humanity has laid onto itself over the past century. That is, their behavior has been caused by greater situations and events that are removed from them and completely out of their control. They are not altogether free from the force of automatism, but they are indeed separate from the automatismatic masses who remain asleep to the realities of the world, if there is indeed any such thing as objective reality which the film also challenges. These are the people who are offended and repulsed by the girls’ behavior. They are shocked, and likewise the film itself through its radical and revolutionary approach to form is meant to shock audiences. The two girls supply a jolt to the people they confront, and the film is meant to do the same to its audiences. Chytilova’s radically avant-garde approach to filmmaking assaults the viewer in every respect. Chytilova destroys the conventions and the expectations of cinema much like how her protagonists destroy social and behavioral norms and expectations. In this way, in Daisies, form compliments content.

There is also the fact, which cannot be ignored, that the two protagonists of the film are female. There is indeed something to be said for their actions in respect to feminism. Feminist criticism often calls for the destruction of traditional forms of representation in order to replace them with new, just forms. To reinsert into the canon of work the female artists that history has ignored, as well as to replace the traditional aim of the visual arts as a male dominated medium. If film is traditionally a medium that constructs a male vantage point and aims to gratify purely male need and fantasy, then feminist film must rearrange the traditional form and aesthetic of representation in order to reverse the male-imposed power relationship. Daisies, in this sense, both prefigures feminism and enacts feminist theory.

The film ends much like it began. The scene in the banquet is arguably the film’s scene of greatest destruction. Much like their behavior throughout the film, the girls indulge in food and drink that does not belong to them, they break bottles, glasses and plates and they destroy, make a real disaster, of an upper class if not state funded banquet hall. Their scene of festivity and jovial destruction leads immediately to a reaction by the girls to clean up their mess, to work. The two appear redressed, but no longer in clothes, rather, bound in papers tied to their bodies with rope. They run nervously around the room, and indeed the scene is shot in fewer frames per second to give it a look of jerkiness and speed, cleaning and trying to fix their mess. All the while that they are cleaning the girls continually recite the rhetoric of work. They, apparently mindlessly, recite over and over that work is good, that they must do their work in order to be happy, as though hard work was a prerequisite to happiness. The strange thing is that they suddenly seem to almost believe it, that their necessity to do work will lead, once the work is done, to happiness. However, no matter how hard they work it does no good whatsoever in cleaning the mess and destruction that they have created. They set bits of broken plate next to one another and assure each other that it is just perfect, as it should be. In this scene work is shown to be absolutely meaningless and worthless, incapable of fixing anything or doing any good at all regardless of how much they praise it. The destruction was too great. The scene does however suggest that these two girls, apparently no longer the same two people that we had become acquainted with throughout the film, are bound by documents that tie them to their work and to a misleading and false ideology of the importance and virtue of work. The documents are manifested visually through the papers that are tied to their bodies. These papers that they wear are like the documents that enforce people to labor and to production quotas, but more importantly they are like the propaganda that tells the masses that to work all one’s life is virtuous and good. All the scenes during the film of collage making and all paper cutting that the girls did comes to mind and suggests that undoing themselves of these papers ought to be quite easy, however they seem helpless to stop working. They seem convinced that they must work before they can be happy, even if the work is obviously worthless since things are too far gone to be fixable anyway. The scene ends with the girls deciding that they have completed their work. They lie down, exhausted but elated, on the table. They smile and say that now that their work is done they are happy. At this moment, maybe because of its thorough and striking contradiction to everything the girls were and did throughout the film, they seem more ridiculous and ingenuine than even at their greatest heights of most ridiculous infantilistic behavior. This awkwardness that the audience is made to feel at this point is deliberate in order to underline the absurdity of the popular rhetoric which suggests that work is the only avenue to happiness. Finally, lying down on the table and in their achievement of “happiness,” the girls suddenly scream as the enormous and decadent chandelier above comes crashing down toward them. The scene cuts and is replaced with images of war, just as the film had begun. The audience is left to wonder, but there can be little doubt as to the chandelier’s devastating capacity. The final scene can be understood as a metaphor for life. The girls are bound by the documents, or laws, conventions and norms of the culture and society to which they belong, and as such they spend their entire life working and working toward the promise of happiness, but once the work is finally over, happiness is still elusive, because then they die. One works their whole life through, obeying the rules and hoping for happiness, and then they die. Daisies reveals the absolute absurdity of it all, and that it is meaningless. The automatism of post modern society is just that, a mindless automatism. The majority of the film, before the concluding scene, is a kind of demonstration of how one can break all social and behavioral expectations and shows that they are not invulnerable. It is also the realization of the desire to scream. To let out all of the pent up emotion associated with a post WWI and WWII world. It is a rebellion and a rejection of the world the way it is, and as such, it is incredibly revealing.

Daisies is iconoclastic in relation to all tradition and previous modes of filmmaking. It seems to say that the old modes are no longer valid. That this absolute madness of filmmaking is the only remaining viable means for expression of such sensitive but revolutionary and explosive issues.- Francisco Lopez

A milestone in the Czech New Wave, Vera Chytilová’s Daisies follows two young girls, both named Marie, as they embark upon an anarchic series of escapades and impromptu happenings. Exclaiming “one should try everything,” they play pranks, get drunk, gorge themselves and engage in all manners of homespun absurdism with complete abandon as Chytilová douses them in shifting colors and random visual effects. A Dadaist comedy shot through with freeform largesse, Daisies is co-written by Ester Krumbachová, who not only worked with Chytilová on its follow-up, We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, but also the darker Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. Held from release by the censors for longer than a year, Daisies was promptly banned after a brief run. But over the years it’s legacy has quietly grown, and it’s influence can be found in Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating and in the irreverent films of Athina Rachel Tsangari (whose Attenberg was released this year) and Jennifer West. “Masterpiece . . . looks better every year—it’s amazing that this feminist Duck Soup is not yet regarded as a classic.”—J . Hoberman

For my latest step on this journey through the Eclipse Series, I find myself in an unusual situation. Most of the time (other than when I’m reviewing a new release set), my effort here is to serve as that proverbial lone voice in the wilderness looking to shed some light and draw some attention to obscure films that aren’t currently generating much buzz. But this week, things are a lot different, in that the title I chose was (unbeknownst to me) right on the verge of a major p.r. campaign on its behalf (well, major by art house standards anyway.) Through the coordinated strategies of Criterion, Janus Films and other key players who all have a stake in its revival tour, Daisies, part of Eclipse Series 32: Pearls of the Czech New Wave, has garnered the attention of major media outlets like the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the Village Voice. Their film reviewers, as well as a host of other specialized cinema and news publications, have all recently given a high profile to this frenetic underground classic, thanks to a new 35mm print that’s touring around the country and playing in New York City this weekend. Besides the publicity for the film itself, Criterion is pulling out all the stops, with Current articles featuring Daisies cut-out paper dolls and a spiffy photo gallery that accompanied the box set’s release back in April.

So I have to ask myself, am I feeling up to snuff to step into the cultural-critical ring with those heavyweights? Or am I content to let them hold court and lay down their authoritative takes on this amazing, unique expression of mid-60s Eastern bloc feminist surrealism without offering my own in-depth analysis of what Vera Chytilova and her collaborators concocted in that special time and place? As it turns out, time pressures and my desire to get this post online ASAP are pressing me to just rattle off my thoughts without thinking it through as much as I usually try to. I have a vacation to pack for and other important things to do, so my approach to this splendid film is to just load up the post with some of my favorite screencaps, allow them to mostly speak for themselves, and sincerely urge you, if you find them at all intriguing or pleasant to gaze upon, to GO SEE THIS FILM – even if the best that you can do is to find a copy of the DVD, should the theatrical print be too long in arriving in your vicinity.

So if you want to learn about Vera Chytilova, who she was and how she staked out her place as the only female director of the Czech New Wave (an audacious achievement on her behalf, given all the pressures she had to overcome to not simply accept a more subordinate role in the government-controlled film industry) you can check out this link. As for a summary of the plot, what Daisies is actually about, there’s not a whole lot to say. Basically, two girls just coming into young adulthood take a quick, disdainful appraisal of the world around them, see how messed up it is, and decide that it’s within their rights to just let themselves be spoiled too. Fueled by the excitement and sense of endless possibilities that this freedom to just go rotten suddenly allows them, the girls (named Maria I, the brunette, and Maria II, the blonde) utilize the resources most obviously at their disposal – namely, their irrepressible cuteness and manic imaginations – to wreak havoc all around them in an ever-so-charming way. Is there a lesson or moral of the story to be gleaned from the string of pranks and chaotic destruction that ensues? I guess it all depends. To the censors, Ms. Chytilova and her defenders asserted that Daisies shows the consequences of an undisciplined, shallow, self-indulgent life. That tidy summary might have carried a bit more gravitas if the girls didn’t appear to be having so damn much fun cutting loose, most often at the expense of respectable and prestigious male authority figures.

So as it turns out, the censors mostly had the upper hand in severely limiting the exposure of Daisies, effectively clamping the film down for a couple years after it was first released in 1966. The Prague Spring of 1968 created enough of an opening for Daisies to blossom through the cracks in the Iron Curtain, where it was seen and felt by enough people to ensure that the seeds would survive to sprout again in the future after a Soviet-led reassertion of control once again relegated the film to the list of seldom-seen contraband over the next couple of decades or so. We can certainly be grateful that this magnificent specimen of flower was preserved, and though exceedingly rare, never quite went extinct.

Aside from it’s inclusion in the Czech New Wave set, Daisies also stands comfortably alongside similarly zany, dadaist comic spectacles like Zazie dans le Metro, the early works of fellow Eastern European auteur Dusan Makavejev and films found in a more recent Eclipse Series release, Up All Night with Robert Downey Jr. There are even some noticeable influences of avant garde filmmakers like Stan Brakhage in some of the rapid edit montages of cut out flowers and other collage work, and randomly applied color filters that fairly scream “just because we can!” as their raison d’etre. Though it’s quite brief (a mere 76 minutes long), there’s so much creativity packed in, and such a rich abundance of visual humor and subversive counter-cultural intelligence running through it all that one could easily schedule twice the time allotted to watch the film once through in order to hit the replay button and take it in again in a single back-to-back sitting. It’s that entertaining, at least in my experience. Amateur leads Jitka Cerhova and Ivana Karbonova don’t necessarily show a lot of acting chops, but that’s no detriment at all. Their inherent playfulness and enthusiasm for the roles they signed on to play spills out with a contagious zeal to simply revel in the glorious mess they’re privileged to create.

But before I declare my unabashed fondness for the girls, I have to pause for a quick reality check, since I’m at the same age and stage of life as the well-dressed fellows that they lured into a series of prankish mock-dates, in which they catered to the egos of past-their-prime suitors, merrily stringing them along until the farce played itself out and the time came to send them packing back to their wives and bourgeois comforts on the next available train. For the men, it’s a depressing reminder of their sapping vitality; for the young women, it’s an elementary exercise in seductive empowerment as we see them effortlessly toy with the men’s feelings and desires, pushing them to the breaking point as they hold out hope that their patient flattery of the pretty young things will eventually yield more immediately gratifying results – only to realize belatedly that they never even had a chance.

Marie I and II periodically retreat to the privacy of their flat, where they dream up future escapades in a rapid-fire torrent of mischievous rebellion without a cause. When they’re together, Marie I seems to take on more of a leader role, setting the tone for whatever stunt they may be working on out in public, with Marie II more often than not pushing back in order to assert her own perspectives in a slightly more passive aggressive manner.

But left to exert her charms as a solo act, Marie II turns out to be quite nimble and fearless. She adopts the name “Julie” and snares a naive young songwriter, whose descent into something he considers love is disarmingly rapid and accurate, at least for those of us who have fallen under similar spells from time to time in our lives.

So what are the Maries up to anyway? What’s their game? We can never really tell with any great precision, simply because the women are presented as true blank slates, without any past, family encumbrances or sense of having a life beyond the narrow confines of their apartment and the various social interactions we observe. As for motivations, they seem to be mainly driven by appetite, but what exactly they’re craving is again never clearly explained. Despite some pretty blatant but incessantly whimsical emasculating imagery involving pickles, sausages, bananas and such, man-hating “revenge” seems too crude, too crass, even though they do express a general contempt for the roles and presumptions imposed upon them by their society. Or if there is some kind of payback motive at work here, their adorable playfulness just masks it all so well. When I stop to think about it a bit, it’s hard to completely shake the feeling that maybe I’m getting strung along here myself. But oh so willingly, as it turns out.

I also think it’s only fair for me to point out that my comments here are just the result of a quick surface reading, which may give the impression that Daisies is simply an indulgence in manic whimsy and bright colors, empllying attractive free-spirited young women to render the whole thing that much more fetching. The eye candy aesthetics and unrestrained slapstick are definitely here in abundance, but there’s more that’s being said by and about the women that I could draw out with further viewing and reflection. If Daisies were nothing more than mere raunch and titillation, it might have been censored but probably would have just as quickly been forgotten. The sexiness of the production is conveyed more by attitude than in graphic images, and it’s pretty clear that what really troubled the Czechoslovakian authorities was the ambiguous complexity of Daisies‘ message more than any overtly anti-government message. The Marias, and by extension director Chytilova, were simply genies that the centralized authorities did not want to let out of the bottle.

In the finest Three Stooges and Marx Brothers tradition, Daisies winds up in an epic food fight, though the stuffed shirts and pompous prigs are nowhere near the scene of the fracas. Instead, it’s Maria vs. Maria as they sneak into a lavishly decked out banquet hall well ahead of whatever guests were intended to be served, and make a complete shambles of the place, much to our delight. The spiral of madness reaches a peak that Chytilova cannot even attempt to rein in without introducing a deus ex machina resolution every bit in keeping with the absurdity that drove us to that point to begin with. The last few minutes of Daisies do represent a legitimate attempt to tie a bow around the chaos, with a lucid editorial point about the human tolerance for war, suffering and mass-killing even as we’re so easily driven to righteous indignation when social customs or rules of decorum are violated.

The drumbeat among fans of Daisies who’d like to see the film issued as a stand-alone blu-ray package has created some interesting speculation as to whether or not this will be the first Eclipse title to make the jump from that sideline label into the Criterion Collection itself. Given that a newly restored print is just now making the rounds, I suppose that makes for a tantalizing possibility, and I for one would enjoy the chance to see this visually captivating film in the highest possible resolution. The clip I embedded above gives just a small preview of Chytilova’s startling techniques. But while I can see the potential value and benefits of a more lavish presentation of Daisies, I also recognize its essential role in this set. Given the fascinating depth of the companion films in the Pearls of the Czech New Wave box, plucking this daisy from the bunch would have diminished the whole project. Chytilova’s ability to work freely did suffer as a result of the censorship she had to endure after she completed Daisies, and as fun as it is to admire in isolation, it’s more important to see how it bloomed in the context of a creative movement of its era.

Mod Madness from Vera Chytilová's New Wave Daisies

Flower power

Marie I and Marie II, the unholy-fool heroines of Vera Chytilová's anarchic Czech New Wave 1966 classic, Daisies, have insatiable appetites: not just for pickles, sausages, bananas, and other suggestively shaped food, but for mayhem in general. Similarly, Daisies, a dada, gaga series of high jinks, oral fixations, and aggressive regression, devours the borders between sense and nonsense. Matching the lunacy of her characters, the formal elements of Chytilová's movie, which BAMcinématek is showing in a new 35mm print for a week-long run, also suggest liberating disorder. A riot of technical tricks, Daisies shifts between color, black-and-white, and tinted images and includes a scene in which the two Maries, wielding scissors, essentially turn themselves into paper dolls.

Chytilová's second feature, Daisies was originally planned as a send-up of bourgeois decadence; the director herself referred to it as "a necrologue about a negative way of life." Yet, too freewheeling and unclassifiable, the film, which Chytilová co-wrote with Ester Krumbachová, gooses anyone hung up on rules: Daisies is dedicated "to those who get upset only over a stomped-upon bed of lettuce."

Born in 1929 and the only female enrolled at the prestigious Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague in 1957, Chytilová devilishly flouts one of cinema's most sacrosanct tenets: creating sympathetic characters. "We're supposed to be spoiled, aren't we?" Marie I (Jitka Cerhová), distinguished by her ponytails and Bardot-ish moue, says to Marie II (Ivana Karbanová), who often wears a crown of the titular flowers atop her strawberry blond bowl cut. The two actresses, both nonprofessionals—Cerhová was a student and Karbanová a salesclerk at the time; both would appear in a handful of films afterward—erupt in Woody Woodpecker–like laughs, their maniacal giggles belying the stealth radicals they're portraying. Think a Laugh-In-era Goldie Hawn on a subversive mission behind the Iron Curtain times two.

Marie I and II—who might just as well be called Thing 1 and Thing 2 for the chaos they create—tease and trick with the faint promise of sex distinguished-looking elderly gentlemen into paying for expensive meals at restaurants until one of the women decides "this isn't fun anymore." Other hobbies include pyromania, rolling down grassy hills, and amateur linguistics ("Why does one say 'I love you'? Why doesn't one say 'egg'?"). Their antics, purposefully wearying, reach maximum pandemonium during a gluttonous episode that soon becomes an orgiastic food fight. These two slim, mod beauties revel in their infantile defilement before swinging from chandeliers and catwalking down the buffet table.

But Czech censors weren't amused and banned Daisies for "food wastage." After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Chytilová, who unlike compatriot Milos Forman, refused to relocate to the West, was prohibited from making films until the mid '70s (though her Daisies follow-up, We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, was released briefly in her native country in 1969 before being pulled from theaters). Daisies has been praised as a feminist triumph—a claim that the director has been loath to embrace. In a tetchy interview with The Guardian in 2000, Chytilová stressed that she preferred "individualism" to "feminism." "If there's something you don't like, don't keep to the rules—break them. I'm an enemy of stupidity and simplemindedness in both men and women, and I have rid my living space of these traits." The pretty nitwits at the center of her most famous film bear out her philosophy.

Chytilová's second feature, Daisies was originally planned as a send-up of bourgeois decadence; the director herself referred to it as "a necrologue about a negative way of life." Yet, too freewheeling and unclassifiable, the film, which Chytilová co-wrote with Ester Krumbachová, gooses anyone hung up on rules: Daisies is dedicated "to those who get upset only over a stomped-upon bed of lettuce."

Born in 1929 and the only female enrolled at the prestigious Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague in 1957, Chytilová devilishly flouts one of cinema's most sacrosanct tenets: creating sympathetic characters. "We're supposed to be spoiled, aren't we?" Marie I (Jitka Cerhová), distinguished by her ponytails and Bardot-ish moue, says to Marie II (Ivana Karbanová), who often wears a crown of the titular flowers atop her strawberry blond bowl cut. The two actresses, both nonprofessionals—Cerhová was a student and Karbanová a salesclerk at the time; both would appear in a handful of films afterward—erupt in Woody Woodpecker–like laughs, their maniacal giggles belying the stealth radicals they're portraying. Think a Laugh-In-era Goldie Hawn on a subversive mission behind the Iron Curtain times two.

Marie I and II—who might just as well be called Thing 1 and Thing 2 for the chaos they create—tease and trick with the faint promise of sex distinguished-looking elderly gentlemen into paying for expensive meals at restaurants until one of the women decides "this isn't fun anymore." Other hobbies include pyromania, rolling down grassy hills, and amateur linguistics ("Why does one say 'I love you'? Why doesn't one say 'egg'?"). Their antics, purposefully wearying, reach maximum pandemonium during a gluttonous episode that soon becomes an orgiastic food fight. These two slim, mod beauties revel in their infantile defilement before swinging from chandeliers and catwalking down the buffet table.

But Czech censors weren't amused and banned Daisies for "food wastage." After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Chytilová, who unlike compatriot Milos Forman, refused to relocate to the West, was prohibited from making films until the mid '70s (though her Daisies follow-up, We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, was released briefly in her native country in 1969 before being pulled from theaters). Daisies has been praised as a feminist triumph—a claim that the director has been loath to embrace. In a tetchy interview with The Guardian in 2000, Chytilová stressed that she preferred "individualism" to "feminism." "If there's something you don't like, don't keep to the rules—break them. I'm an enemy of stupidity and simplemindedness in both men and women, and I have rid my living space of these traits." The pretty nitwits at the center of her most famous film bear out her philosophy.

Ovoce stromů rajských jíme / Fruit of Paradise

Wild, extravagant and audacious 35mm film! Nominated for the Palme d’Or in 1970, Věra Chytilová’s Fruit of Paradise can be considered a ‘lost’ masterpiece. Originally censured, and never widely distributed, it’s a brilliantly executed aesthetic exercise - formalism at its most sensual and intoxicating. Distinctly whimsical, seriously slapstick and precociously performative, expect beach balls, musique concrète, and manhunts in Chytilová’s brilliantly flawed, brilliantly beautiful Shangri-la.

Věra Chytilová's Ovoce stromů rajských jíme (Fruit of Paradise, 1969) is an audacious combination of allegorical narrative and the avant-garde. Above all, it plays with the idea of searching for "truth" and questions our ability to accept it. It is a reflection on the nature of the film itself, as well as a personal testament of its reputedly "cynical" director's commitment to "telling the truth." It is a vivid testimony to the role of the "avant-garde" in 1960s Czechoslovak cinema. It is an ascendant of what Eisenstein described as "intellectual cinema."

However, montage is more or less dispensed with, in favour of a plethora of visual associations and mental juxtapositions that are orchestrated through a succession of semi-improvised "happenings." As Peter Hames has acknowledged, it boldly defies any "realistic" interpretation, yet encourages "active interpretation," demanding that the viewer construct his or her own meaning.

Like its precursor Sedmikrásky (Daisies, 1966), it is thoroughly "post-modernist" in the sense of the playfulness implied by the term. Yet, contrary to the opinion of its state sponsor, Chytilová's reckless playfulness doesn't invite nihilism. Ovoce stromů rajských jíme may be more obscure than Sedmikrásky, but it remains a resoundingly "mainstream avant-garde" film, a brilliantly executed aesthetic exercise. It is formalism at its most beautiful.

I have not shared the Czechoslovak experience, nor can I share Chytilová's quasi-feminist point of view. Mine, like appreciation of any kind, is an outsider's view.

All the bright young women

As in the case of Sedmikrásky, Ovoce stromů rajských jíme is the result of the interplay of several talents. Ester Krumbachová devised the scenario and collaborated with Chytilová on the final screenplay. She also provided the décor and costume design. Jaroslav Kučera, then Chytilová's husband, developed several of his ideas about color use, not to mention various photographic effects, introduced in his cinematography for Sedmikrásky. In addition to Krumbachová and Kučera, Zdeněk Liška's score structures Chytilová's parable, giving it an operatic quality.

Chytilová originally studied architecture, then philosophy. After a stint as a model, she worked as a script girl in a film studio. Having been refused recommendation, let alone a scholarship, Chytilová obstinately battled her way into FAMU, the Czech film school.

Like Miloš Forman, Chytilová's early work was strongly influenced by cinema verité, though her graduation film Strop (Ceiling, 1963) and the subsequent Pytel blech (A Bagful of Fleas, 1963) were "staged" improvisations with non-actors.

If O něčem jiném (Something Different, 1963) challenged conventional narrative forms of "realism," then Sedmikrásky reconstituted conventional narrative forms entirely. According to Chytilová, Sedmikrásky is a "philosophical documentary in the form of a farce," her strategy is to divert the spectator from emotional involvement, destroy psychology and accentuate humour.

However, it is the aesthetic form of Sedmikrásky that breaks new ground. Jaroslav Kučera deserves credit in this respect: Kučera's talent as a cinematographer became evident in Vojtěch Jasný's Až přijde kocour (Cassandra's Cat, 1963). He also created the grimy aesthetic textures of Němec's remarkable Démanty noci (Diamonds of the Night, 1964).

Krumbachová attended the Academy of Applied Arts and became a costume designer, first in theatre and then in film. According to Josef Škvorecký, her rise was not very smooth, and was interrupted by several falls caused by her excessive outspokenness. Finally she established herself in the Barrandov studios as a costume designer. She embarked on a professional and personal relationship with Němec starting with Démanty noci, and culminating in two seminal collaborations, O slavnosti a hostech (The Party and the Guests, 1966) and Mučedníci lásky (Martyrs of Love, 1967). Krumbachová's first involvement with Chytilová was re-writing Pavel Juráček's script for Sedmikrásky.

Production history

Démanty noci, Sedmikrásky, O slavnosti a hostech and Mučedníci lásky all deal with parasites, failures and the persecutions of non-conformists. They are resoundingly negative and obviously undesirable from a Socialist ideological stance.

In 1967, both Sedmikrásky and O slavnosti a hostech were banned from export and the government voted to withhold funds from both Chytilová and Němec so that they would be powerless to realise their "vehicles of nihilism." Chytilová herself was accused of being an elitist, making cynical, uncommitted pessimistic films that were experimental by nature, overvalued by critics and appreciated primarily in the West.

At the height of the so-called "New Wave," 30 feature length films were produced at Barrandov alone. As Forman then pointed out, "We are a little country with 14 million people, and 37 features a year can hardly break even in Czechoslovakia alone. They pay their way by export and foreign exchange and it is the art films that are wanted abroad."

It was this international appeal that attracted the attention of foreign producers. Carlo Ponti produced Forman's Hoří, má panenko (The Firemans' Ball, 1967), and Maurice Ergas co-produced Juraj Jakubisko's Zbehovia a pútnici (The Deserter and the Nomads, 1968).

Following their production of Jerzy Skolimowski's Le Depart (1966), the Belgian Company Elizabeth Films co-produced Ovoce stromů rajských jíme in 1969. It was first shown (and generally misunderstood) at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival.

American critics gave Chytilová the benefit of the doubt, awarding Ovoce stromů rajských jíme the main prize at the 1970 Chicago Film Festival. One critic wrote at the time that it was a

|

| Ovoce stromů rajských jíme: Before its time? |

Prologue

The credits are beautifully hand-painted in the style of flora, presumably by Krumbachová. The soundtrack brings together three elements: avant-garde vocal "adventures" à la György Ligeti; concrete sounds sourced from the cries of a peacock; and the chimes of a bell.

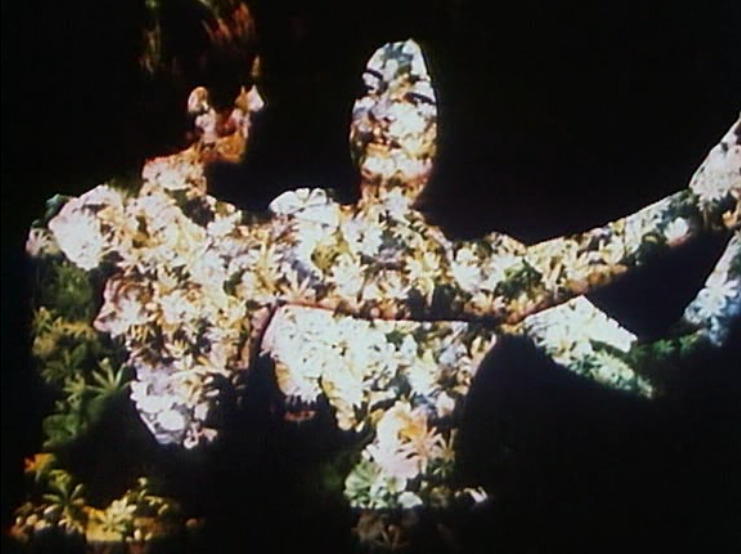

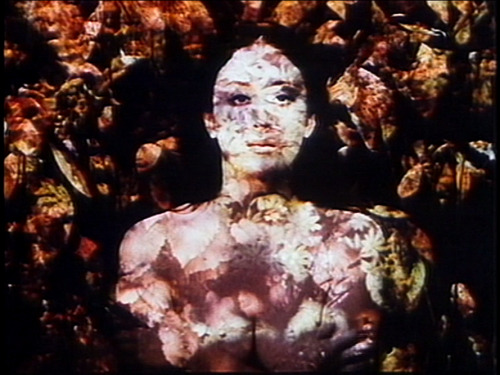

We are then presented with a remarkable sequence involving the naked bodies of Adam and Eva (Eve in English) used as screens for a sequence of close-ups of flora. In addition, the images are saturated in primary colours. Gradually, images of particular flowers emerge in some sort of sequence, appearing with and without the bodies of Adam and Eva. Here, the soundtrack gives way to a more organised piece, using choral music and a simple percussion arrangement.

The central "panel" of the prologue consists of the couple posed Bosch-like in various tableaux, reminiscent of the visual style of mature films by Paradjanov. Quotations from Genesis are transformed into cantata on the soundtrack, recounting how if the couple eat the fruit from the tree of knowledge, it will result in their death. This is contradicted by the serpent, which is represented by a stylised model coiling around a tree trunk, animated by sudden jerks of the camera, first up and down, then left to right.

Finally, the sequence ends with a medium shot of a beautiful dark-haired girl with pronounced Slavic features folding her hands over her breasts. The image is cast in a predominant yellow, and autumnal leaves are projected onto the girl's skin. This is followed by a long shot of the couple kissing in the stream, accompanied by chants of "tell me the truth" on the soundtrack. The floral patterns reappear before an apple drops out of this veritable tapestry into the hand of Eva, now in recognisable "reality."

Like the opening of Bergman's Persona (1966), the prologue offers a microcosm of the content of the film. Adam and Eva are literally part of a paradise broken by the serpent / devil / liar, descending from the tree of knowledge to Eva's demand for truth. Like Sedmikrásky, Chytilová offers this "straight" exposition from the outset, and the rest of the film is not so much a fiction, but rather an explanation, a description of events.

Visually, the emphasis on colour and texture bears comparison with the American avant-garde of the 1960s. In fact, on a trip to New York in 1967, Kučera described how he found "many points of contact" with filmmakers in the New York Underground scene, especially Ed Emshwiller. By contrast, Chytilová's "organised improvisation" recalls the "happenings" of Ken Jacobs and Jack Smith, the most obvious examples of which would be Flaming Creatures (1963) and Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), though Chytilová's approach is admittedly altogether more "serious."

In search of truth

Ovoce stromů rajských jíme is based on a series of encounters between Eva and Robert. The prologue resonates throughout these encounters. Initially, Robert (dressed in red) is framed stretched snake-like across an overhead branch. Most of the action during the first part of the film surrounds Robert's leather satchel. The satchel first appears discarded in a tree whilst Robert and Eva exchange (admittedly absurd) pleasantries whilst he urinates.

Crucially, this scene takes place next to a stone wall, which Eva has climbed over to pick fruit for Josef. The significance of the wall only becomes clear during the final sequences of the film. In contrast to Robert, Josef is dressed in grey, and his behavior is marked by his perfunctory interest in Eva.

Robert's infidelity is suggested in two sequences. In the first, he receives a scented love-letter that he dismisses as "nothing." The second, however, is contained in a bizarre collective ball game.

|

| Beach games and infidelity |

The sequence is photographed in close-up using a distorting wide-angle lens. It's subsequently printed in a way that omits alternate frames, producing a cranked-up effect that should be funny, but here it appears to be rather ominous, like the movements of a spider. The sound of footsteps prompts Eva to hide behind the curtains, horror-film style. There she finds the briefcase. Inside the briefcase she finds lace and a pile of rubber stamps. She rolls over, draws up her skirt and stamps her thigh above her garter with the number six in red ink. Combined with the tension of Eva's trespassing, the sequence is perversely erotic, and recalls the most famous scene of Jiří Menzel's Ostře sledované vlaky (Closely Observed Trains, 1966).

Back on the beach, we learn that a serial killer is stalking nymphettes, leaving their bodies stamped with a red number six. Eva's search for the "truth" behind Robert has resulted in literally marking herself out as one of his victims. With this brew of a devilish serial killer, a mysterious key and indelible red / blood ink, Krumbachová and Chytilová appear, above anything else, to be alluding to the Blue Beard fairytale.

Courting the father of lies

The final section of the film is a tour-de-force of colour, technique and formalism. Robert chases Eva through a forest. She's wearing a white dress and is wrapped in an enormous red scarf. The sequence takes place at dusk, and again Kučera uses a distorting wide-angle lens and omits frames to give a bizarre comic / disturbing motion effect.

The music is dramatic, and the sequence climaxes with Robert grabbing hold of the scarf and the couple tugging at each end. The resulting image is startling to say the least: an autumnal forest bisected by a band of vibrant red flanked by two posing figures. Eva hides behind a tree, and submits to Robert as he wraps the red scarf around her white dress. She steps out of the scarf in a red dress, pre-empting similar devices employed by Paradjanov in Sayat Nova (The Colour of Pomegranates, 1969).

In the final scene between Eva and Robert, the couple strike highly stylized poses by the lakeside. Robert is destined to kill Eva, despite their love for one another. Robert's final words are "Everything is nothing but a dream. You are a lie." Robert falls at Eva's feet to the sound of a gun shot. She finds both a gun and a rose in the pocket of Robert's coat, which she is wearing.

Hames writes that "apart from suggesting the death of a loved one, this juxtaposition could also be interpreted to mean that the intensity and delusions of romantic love can be resolved only in death." The absurdity of Robert's death—being shot by a gun in Eva's pocket—consolidates his claim that "everything is nothing but a dream," and therefore the truth cannot be found.

Eva runs from the crime scene in red. She frantically attempts to climb over the wall which she climbed over at the beginning of the film, implying her exclusion from the garden / paradise. Eva's red cloak is rhythmically blurred—a technique that anticipates Christopher Doyle's cinematography for Wong Kar-Wai's Chongqing senlin (Chunking Express, 1994) and Duoluo tianshi (Fallen Angels, 1995). The choral chants of "tell me the truth" return from the prologue of the film.

The finale has Eva confronting Josef in a snow-covered field, in front of a large mansion. She cries out: "Don't try to find out the truth, I no longer wish to know." Eva offers the rose in front of the camera lens, and the film ends with another chant from Genesis: "And they knew they were naked, then they heard God, they hid from his eyes, they hid away among the trees of the garden."

The final shot is a somber black and white shot of solarized waving grass. The end credit resumes the floral typography used in the opening credits, though here the plants are stunted and withered. The exclusion from the Garden is, for Chytilová, an event which is not to be celebrated.

Hard to tell the truth?

According to Antonín Liehm, when Strop was screened in France during the mid-1960s, someone stood up after the film and proclaimed: "they shouldn't make that kind of film. It undermines people's faith in Socialism. If that is the way it really is, then none of it is worth it at all." People want to be deluded, for the truth is often unpalatable. In Ovoce stromů rajských jíme, Chytilová's question is this: can we live with the truth? As Liehm says:

Generally speaking, the film is about the unequal struggle between a man and a woman. And over it all is the question of the ability to accept the truth—whether a person would actually be capable of living with the ideals he advocates, capable of deserving them. It is much easier to fight for truth than to live with it. Ester Krumbachová quotes Robinson Jeffers' poem about Ferguson, a fellow who screamed for truth but was in fact incapable of accepting even a glimmer of it.Strop, O něčem jiném and Sedmikrásky argue that we can only live with the truth. Through a mixture of cinema verité and straight exposition, Chytilová has attempted to unmask illusions and preconceptions, and it's a patronising mistake to assume that her target is "just" aspects of femininity. Her films are often labeled cynical, which, as Liehm points out, is the universal human defense against the truth.

Krumbachová response was simple:

I have often been accused of being a cynic, simply because I refused to believe everything I was told. I think that Hitler showed quite clearly what happens when humanism is replaced by grandiose goals and projects. Concentration camps, the occupation—those were fantastic realities which showed people as they really are. That's why it is no longer possible to get down on your knees and offer up thanks to God. Gods have vanished, and so have the myths and illusions about the goodness of man. But some people remain children; they are incapable of abstraction and confuse symbols with realities. But that's another story."A writer's job is to tell the truth," wrote Hemingway, and, as Škvorecký points out, nobody understands that banality so well as people who, because they were denied the freedom of artistic expression for most of their lives, do not find it banal.- Daniel Bird

Fruit of Paradise

Adam and Eve, bathed in glowing textures of leaves, pebbles, flowers and bark, descend a grassy slope and slip into a pond. Their movements are tentative and yet stiff and choreographed. They wear nothing, but are wrapped snuggly in double-exposures of nature-imagery tinted in bright autumn colors. Passages from Genesis are chanted as part of the angelic score.

Adam and Eve, bathed in glowing textures of leaves, pebbles, flowers and bark, descend a grassy slope and slip into a pond. Their movements are tentative and yet stiff and choreographed. They wear nothing, but are wrapped snuggly in double-exposures of nature-imagery tinted in bright autumn colors. Passages from Genesis are chanted as part of the angelic score. This prologue to Vera Chytilova “Fruit of Paradise” (1970) might easily serve as a standalone short, but it also works as a fitting introduction to this odd adaptation of the Biblical fall. It confirms Chytilova’s commitment to powerful visual impressions, multilayered freeform symbolism and winking witty anarchy. “Fruit of Paradise” is an experimental film that speaks in a similar visual vocabulary as “Daisies” (1966), the audacious era-defining Czech film that established Chytilova’s reputation, but without really feeling like it repeats itself.

This prologue to Vera Chytilova “Fruit of Paradise” (1970) might easily serve as a standalone short, but it also works as a fitting introduction to this odd adaptation of the Biblical fall. It confirms Chytilova’s commitment to powerful visual impressions, multilayered freeform symbolism and winking witty anarchy. “Fruit of Paradise” is an experimental film that speaks in a similar visual vocabulary as “Daisies” (1966), the audacious era-defining Czech film that established Chytilova’s reputation, but without really feeling like it repeats itself. The film follows Eva’s relationship with two men after she bites into forbidden fruit under a tree at a gorgeous garden retreat. Her stern husband finds little joy in the overgrown paradise and frequently flirts with other vacationers. The handsome if rather menacing Josef is an increasingly preoccupation for Eva despite his own incessant flirting and her growing certainty that he is a deranged serial killer. As she spends her days lolling on the beach, frolicking through the underbrush and exploring shady nooks, she feels the growing pressures of love, freedom, danger and temptation.

The film follows Eva’s relationship with two men after she bites into forbidden fruit under a tree at a gorgeous garden retreat. Her stern husband finds little joy in the overgrown paradise and frequently flirts with other vacationers. The handsome if rather menacing Josef is an increasingly preoccupation for Eva despite his own incessant flirting and her growing certainty that he is a deranged serial killer. As she spends her days lolling on the beach, frolicking through the underbrush and exploring shady nooks, she feels the growing pressures of love, freedom, danger and temptation. Following “Fruit of Paradise” as a conventional story, say a love triangle or a murder mystery, is almost entirely impossible. The narrative progress is much like an extended camping trip, with plenty of room to play around and little need for drama or dialogue. The tone is usually lighthearted, to the point where scenes that would typically involve tension or fear are subverted. Joseph, in particular, bounces back and forth from jolly skirt-chaser to intimidating villain quite erratically.

Following “Fruit of Paradise” as a conventional story, say a love triangle or a murder mystery, is almost entirely impossible. The narrative progress is much like an extended camping trip, with plenty of room to play around and little need for drama or dialogue. The tone is usually lighthearted, to the point where scenes that would typically involve tension or fear are subverted. Joseph, in particular, bounces back and forth from jolly skirt-chaser to intimidating villain quite erratically. That’s not to say that the film is in any way boring. The surreal carefree atmosphere is quite welcoming, and draws the viewer into Eva’s miniature ambling adventures. Her curiosity and mischievousness are infectious.

That’s not to say that the film is in any way boring. The surreal carefree atmosphere is quite welcoming, and draws the viewer into Eva’s miniature ambling adventures. Her curiosity and mischievousness are infectious.Meanwhile, Zdenek Liska’s rapturous nearly wall-to-wall score envelops us in an unfettered, often exuberant, soundscape where harmonized voices or lilting instruments sound off at the slightest provocation. Taken along with his work for Vlacil’s “Valley of the Bees” and “Marketa Lazarova,” Liska is becoming a fast favorite for me.

After the first few loosely-connected episodes the feeling of confused anarchy gradually gives way to an understanding of the underlying organization. Scenes are constructed around visual motifs, based around bold points of contrast nestled within the sand and stone or the grass and leaves. Sometimes these contrasts might be built around the shock of seeing elegant Victorian furniture in places more suitable to park benches.

Occasionally the contrasts are based around movement, like a biker or frolicker, passing through the leisurely stillness of nature. Usually Chytilova has figures move in fluid graceful arc, fitting with gentle winds and unrushed pace, but sometimes she drops frames or manipulates the speed to make the characters seem like jerky marionettes.

Occasionally the contrasts are based around movement, like a biker or frolicker, passing through the leisurely stillness of nature. Usually Chytilova has figures move in fluid graceful arc, fitting with gentle winds and unrushed pace, but sometimes she drops frames or manipulates the speed to make the characters seem like jerky marionettes. Most often, the contrast is a spot of bright orange or red set against the greenery.

Most often, the contrast is a spot of bright orange or red set against the greenery.

These sharp highlights not only guide the eye, they are also central to shaping our mood, emotions and even our interpretations. Chytilova is confident enough in her style to accept the ambiguity this creates, since reactions to such compositions necessarily vary from viewer to viewer. There are many occasions where objects are clearly meant to have very specific meanings, but it’s the visual presentation of the objects that tells us how to interpret them.

These sharp highlights not only guide the eye, they are also central to shaping our mood, emotions and even our interpretations. Chytilova is confident enough in her style to accept the ambiguity this creates, since reactions to such compositions necessarily vary from viewer to viewer. There are many occasions where objects are clearly meant to have very specific meanings, but it’s the visual presentation of the objects that tells us how to interpret them. As an example, one might take a scene where Eva violently plays the drums in a dusty attic. One could certainly ask “What do the drums mean?” especially since they don’t’ seem to fit with the other props we’ve seen in the film. Still, I think a better avenue towards understanding is to ask “How does it feel to play the drums?” and to examine the visual and aural sensations that Chytilova is trying to convey.

As an example, one might take a scene where Eva violently plays the drums in a dusty attic. One could certainly ask “What do the drums mean?” especially since they don’t’ seem to fit with the other props we’ve seen in the film. Still, I think a better avenue towards understanding is to ask “How does it feel to play the drums?” and to examine the visual and aural sensations that Chytilova is trying to convey. Unraveling the allegory at hand might at first seem to be quite exhausting, but Chytilova doesn’t ask us to switch into academic mode to enjoy or even understand the film. I think there’s quite a few forbidden fruits planted for the audience to savor, particularly a gleeful hedonism for texture, detail and music. The religious references are not to be thrown away, but they are there more to shape our interpretation rather than to define it; to set our minds in motion rather than to nail it in place.

Unraveling the allegory at hand might at first seem to be quite exhausting, but Chytilova doesn’t ask us to switch into academic mode to enjoy or even understand the film. I think there’s quite a few forbidden fruits planted for the audience to savor, particularly a gleeful hedonism for texture, detail and music. The religious references are not to be thrown away, but they are there more to shape our interpretation rather than to define it; to set our minds in motion rather than to nail it in place. I like to think of Chytilova’s style as a combination of “universal” symbols and personal inflections where cinematography literally colors our interpretation or potentially undermines it. This helps explain the way a single symbol-object can have two or more potentially inconsistent meanings for the director. One example is the way “forbidden fruit” is used as a mark of rebellion and transgression in “Daisies” and as a symbol of awakening, temptation and disillusionment in “Fruit of Paradise.” Sometimes the connotation of a symbol can change many times within a single film.

I like to think of Chytilova’s style as a combination of “universal” symbols and personal inflections where cinematography literally colors our interpretation or potentially undermines it. This helps explain the way a single symbol-object can have two or more potentially inconsistent meanings for the director. One example is the way “forbidden fruit” is used as a mark of rebellion and transgression in “Daisies” and as a symbol of awakening, temptation and disillusionment in “Fruit of Paradise.” Sometimes the connotation of a symbol can change many times within a single film. This is part of why I feel the director’s films resist straightforward feminist readings. As a female director who prefers female protagonists and adopts many of the stereotyped mainstays of feminist art (nature themes, sensation-driven narratives, anti- institutionalism, rejection of psychoanalytic theory, etc.), Chytilova is too often pigeon-holed as purely preoccupied with gender issues. Like most surrealists, I think she has eclectic interests and multiple goals, many of them quite nuanced and personal. In appreciating her films, one must be careful not to warp her intentions in the places where a classical feminist mold doesn’t fit.

This is part of why I feel the director’s films resist straightforward feminist readings. As a female director who prefers female protagonists and adopts many of the stereotyped mainstays of feminist art (nature themes, sensation-driven narratives, anti- institutionalism, rejection of psychoanalytic theory, etc.), Chytilova is too often pigeon-holed as purely preoccupied with gender issues. Like most surrealists, I think she has eclectic interests and multiple goals, many of them quite nuanced and personal. In appreciating her films, one must be careful not to warp her intentions in the places where a classical feminist mold doesn’t fit.If you’re a fan of “Daisies,” or the brand of visually accomplished surrealism I’m often advocating (“Valerie and Her Week of Wonders,” “The Hourglass Sanatorium,” “Eden and After,” “El Topo,” “A Zed and Two Noughts,” etc.) then this is another film worth checking out. This formerly very rare film is now readily available through Netflix thanks to a not-to-shabby release by Facets.

With authoritarian communism rearing its ugly culture-distorting redhead in Czechoslovakia with the Soviet invasion of the country in 1968, foremost female Czech New Wave auteur Vera Chytilová (O necem jinem aka Something Different, Kalamitaaka Calamity) found her highly creative and insanely idiosyncratic filmmaking career put on hold just at the time it begin to both nationally and internationally flourish. After completing her most well known and critically revered work Sedmikrásky(1966) aka Daisies, which was banned upon its initial release in 1966 until 1967 largely due to its gratuitous waste of food (!), Chytilová directed one more film, Ovoce stromů rajských jíme (1970) aka Fruit of Paradise aka We Eat the Fruit of the Trees of Paradise, before she was unofficially blacklisted and was forced to work in the undignified world of television commercials using her husband Jaroslav Kucera’s name just so she could make ends meant. Fruit of Paradise was the first Chytilová film I ever saw and in my opinion it is the filmmaker’s masterpiece as a uniquely uncompromising and thematically/aesthetically intricate work that even seems to transcend Daisies. Like much of Chytilová oeuvre, especially Daisies, Fruit of Paradise is oftentimes incorrectly described as a feminist flick when, in fact, as the auteur has mentioned in various interviews, it is an anti-Soviet parable. An innately anarchistic yet equally operatic reworking of the biblical Adam and Eve story set in a hippie-like outdoors health resort of the exceedingly if not somewhat misleadingly ethereal sort, Fruit of Paradise managed to be entered in competition at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, but not unsurprisingly, the work was poorly received because apparently nobody could understand it. Indeed, as much as I appreciate anti-communist flicks, Fruit of Paradise succeeds most in its daringly decadent and superlatively self-indulgent aestheticism as a keenly kaleidoscopic work that manages to even rival the high-camp Kulturscheisse films of kraut dandy Werner Schroeter. Not unlike American auteur E. Elias Merhige’s rather uneven black-and-white experimental flick Begotten (1990), Fruit of Paradise begins with a positively penetrating 10-minute prologue that is a virtual film in and of itself and could easily work as a stand-alone short, but what really makes Fruit of Paradise is that it is endlessly enthralling as a sort of beauteous bastard lunatic celluloid love child of Kenneth Anger and Gábor Bódy. A work that essentially proves that Chytilová is the only rightful heir to Maya Deren and an anti-communist flick from a leftist that is no less hyper hermetic than the works of Dušan Makavejev, Fruit of Paradise is ultimately a film that reminds the viewer why the devil wears red. And as they say, better dead than red...