Marie Menken utjecala je na Warhola, Angera, Mekasa i Brakhagea a prema njoj je stvoren ženski lik u drami/filmu Tko se boji Virginie Woolf?

Marie Menken was born Marie Menkevicius in New York City on May 25, 1909, the daughter of Catholic Lithuanian immigrants. She grew up in Brooklyn with a brother and a sister, in a home used to frequent financial difficulties. Both she and her sister Adele later changed their surname to Menken. Marie Menken and Willard Maas had got married in 1937, moving into a Brooklyn penthouse at 62 Montague Street which they would inhabit until their deaths. She died on December 29, 1970. Four days after her death, on January 2, 1971, Willard Maas died.

Marie Menken Notebook

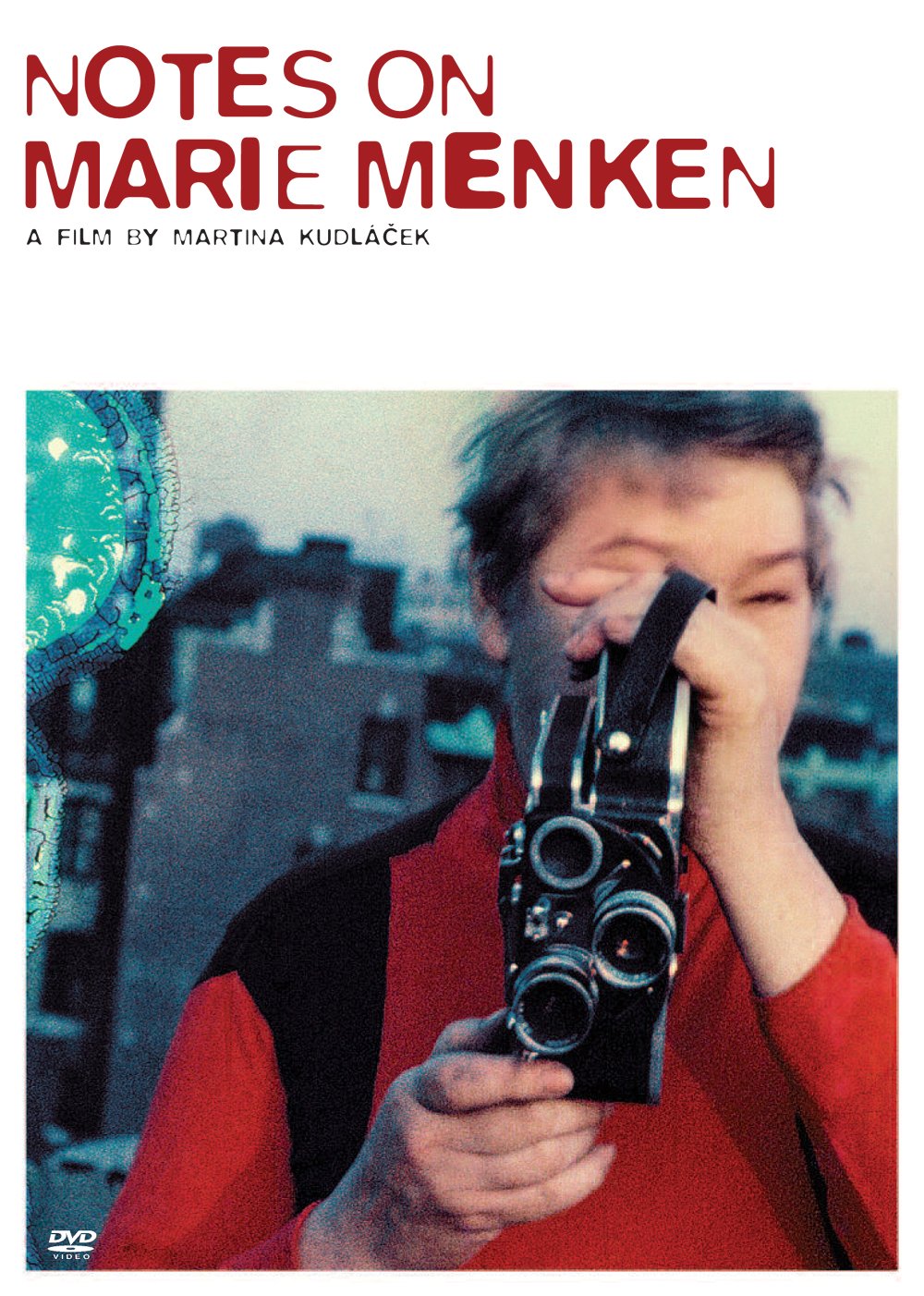

American filmmaker Marie Menken was born on this day in 1909. It was through Charles Henri Ford, as we have seen, that Menken first came into contact with Andy Warhol. Martina Kudláček’s 2006 documentary Notes on Marie Menken (which I can’t recommend highly enough) preserves an encounter between the two on the roof of Menken’s apartment building, in which they spar with cameras, circling each other, lunging and generally goofing off in a way we wouldn’t ordinarily associate with the inscrutable Pope of Pop.

In 1965 Menken produced a short film portrait of Warhol at the Factory. Warhol’s long-term assistant Gerard Malanga, for whom Menken was a kind of mother figure, also features prominently. The pair work with an industry which lives up to the Factory’s name, reminding us that Warhol’s studio wasn’t just a crèche for speed-crazed socialites.

Much of Andy Warhol (in two parts, below) is shot at the frenetic pace familiar from earlier Menken films such as Go! Go! Go!. There’s Warhol making silkscreen prints of Jackie Kennedy, Warhol walking past said images in a repeating loop like a cheap Hanna-Barbera cartoon backdrop, Warhol wrapping Brillo boxes for an exhibition. At the gallery opening, the social whirl speeds up to a blur. One of the few reflective moments in the film comes when Menken goes to an industrial facility where actual Brillo boxes are being loaded onto trucks. She seems to define the art world as a heedless rush of mass production and grinding routine compared to the more rarefied realm of manufacturing and dispatch.

Menken’s best-known cinematic association with Andy Warhol came the following year, with her role in his film Chelsea Girls. It’s unfortunate that her appearance preserves little of the ingenuity, warmth and generosity of spirit remarked upon by all who knew her. Instead she turned in the kind of drunken, cantankerous rant she would occasionally direct at her closeted husband Willard Maas, episodes which so inspired Edward Albee as he was writing Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

- strangeflowers.wordpress.com/

“Notes on Marie Menken” shines a quavering if welcome ray of light on a largely forgotten figure in the American avant-garde film scene of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, a strange, unwieldy figure who, moreover, happened to be the inspiration for that harridan of all times: Martha in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”

Until now, if you had wanted to know about Marie Menken, a Brooklyn-based exhibited painter turned experimental filmmaker, whose sphere of influence included not just Edward Albee but also Stan Brakhage and that ageless enfant terrible Kenneth Anger, your search would have been mostly relegated to the margins. She pops up a few times in P. Adams Sitney’s history of American avant-garde cinema, “Visionary Film,” and makes minor appearances in books about Andy Warhol, in part because of her gargoyle-like appearance in his 1966 dual-screen epic, “The Chelsea Girls.” Wearing a wide-brimmed hat and beaded necklace, her eyes nearly swallowed up by the puffy swells of her face, Ms. Menken strikes a singularly unglamorous, obstreperous note in the film: the Superstar as babushka.

She was in her mid-50s when she appeared in “The Chelsea Girls” and easily looked 20 years older. By then she had shot a number of ephemerally beautiful, short personal films, some of which she bundled together with deliberate casualness and called “Notebook.” Her nominal subjects in these and other films were seemingly straightforward and simple — a nodding flower, a droplet of rain on a leaf, showily patterned tiles, a gurgling fountain, pigeons tracing loops across the sky — but only in the way that everyday life is straightforward, simple and profound. You feel Ms. Menken’s presence in every gently trembling shot, which seems to quiver with the excitement of life, as if she were discovering the world anew in each image.

The joyfulness of those images feels at odds with that bloated figure presented by Warhol in “The Chelsea Girls.” Martina Kudlacek, the director of “Notes on Marie Menken,” isn’t all that big on the finer points of biography, so the viewer is left more or less alone to bridge the apparent divide between the filmmaker and her work. There are clues, including her husband’s homosexuality. Ms. Menken might have been happy in her marriage to the filmmaker and writer Willard Maas, but it’s hard not to think that there was some pain mixed in with all that bohemian free loving and living. Certainly the couple’s monumental boozing and arguing, which inspired Mr. Albee so memorably, suggests that there might have been some self-medication in the mix.

In his touching Village Voice obituary for Ms. Menken, who died in 1970 at 61 after a short illness, Jonas Mekas wrote: “There was a very lyrical soul behind that huge and very often sad bulk of a woman, and she put all that soul into her work. The bits of the songs that we used to sing together were about the flower garden, about a young girl tending her flower garden. Marie’s films were her flower garden. Whenever she was in her garden, she opened her soul, with all her secret wishes and dreams. They are all very colorful and sweet and perfect, and not too bulky, all made and tended with love, her little movies.”

What Mr. Mekas doesn’t mention is that the title subject in one of Ms. Menken’s earliest films, “Glimpse of the Garden,” belonged to one of her husband’s former male lovers. (This intimate connection might explain why the film is not titled “Glimpse of a Garden.”) There is something terribly moving about this biographical detail, which goes unmentioned in the documentary as well, because it suggests a generosity of soul — or, perhaps, more rightly, an insistence on life and self-affirmation — already evident in Ms. Menken’s images. Behind these delicate yet resilient, unmistakably feminized flowers, we intuit someone who could find beauty in the world, no matter how badly that world might have treated her. And not just find beauty, but also return it to the world, though on her own emphatic terms.

Ms. Kudlacek omits much: she never tells us whether Ms. Menken formally studied art (she did, including at the Art Students League); it’s even unclear if she and Mr. Maas had any children. The death of a child is mentioned almost in passing in the film, but in a published interview Mr. Anger, who lived with the couple for a short time, mentions visits from a son.

Still, salient details and observations emerge in the documentary, principally through interviews with the likes of the painter and filmmaker Alfred Leslie and especially the poet and photographer Gerard Malanga, who studied with Mr. Maas and whose tender recollections of Ms. Menken suggest that, while any biological children remain shrouded in mystery, there were loving surrogates nonetheless. Marie Menken’s garden bloomed, and not only on film.

Until now, if you had wanted to know about Marie Menken, a Brooklyn-based exhibited painter turned experimental filmmaker, whose sphere of influence included not just Edward Albee but also Stan Brakhage and that ageless enfant terrible Kenneth Anger, your search would have been mostly relegated to the margins. She pops up a few times in P. Adams Sitney’s history of American avant-garde cinema, “Visionary Film,” and makes minor appearances in books about Andy Warhol, in part because of her gargoyle-like appearance in his 1966 dual-screen epic, “The Chelsea Girls.” Wearing a wide-brimmed hat and beaded necklace, her eyes nearly swallowed up by the puffy swells of her face, Ms. Menken strikes a singularly unglamorous, obstreperous note in the film: the Superstar as babushka.

She was in her mid-50s when she appeared in “The Chelsea Girls” and easily looked 20 years older. By then she had shot a number of ephemerally beautiful, short personal films, some of which she bundled together with deliberate casualness and called “Notebook.” Her nominal subjects in these and other films were seemingly straightforward and simple — a nodding flower, a droplet of rain on a leaf, showily patterned tiles, a gurgling fountain, pigeons tracing loops across the sky — but only in the way that everyday life is straightforward, simple and profound. You feel Ms. Menken’s presence in every gently trembling shot, which seems to quiver with the excitement of life, as if she were discovering the world anew in each image.

The joyfulness of those images feels at odds with that bloated figure presented by Warhol in “The Chelsea Girls.” Martina Kudlacek, the director of “Notes on Marie Menken,” isn’t all that big on the finer points of biography, so the viewer is left more or less alone to bridge the apparent divide between the filmmaker and her work. There are clues, including her husband’s homosexuality. Ms. Menken might have been happy in her marriage to the filmmaker and writer Willard Maas, but it’s hard not to think that there was some pain mixed in with all that bohemian free loving and living. Certainly the couple’s monumental boozing and arguing, which inspired Mr. Albee so memorably, suggests that there might have been some self-medication in the mix.

In his touching Village Voice obituary for Ms. Menken, who died in 1970 at 61 after a short illness, Jonas Mekas wrote: “There was a very lyrical soul behind that huge and very often sad bulk of a woman, and she put all that soul into her work. The bits of the songs that we used to sing together were about the flower garden, about a young girl tending her flower garden. Marie’s films were her flower garden. Whenever she was in her garden, she opened her soul, with all her secret wishes and dreams. They are all very colorful and sweet and perfect, and not too bulky, all made and tended with love, her little movies.”

What Mr. Mekas doesn’t mention is that the title subject in one of Ms. Menken’s earliest films, “Glimpse of the Garden,” belonged to one of her husband’s former male lovers. (This intimate connection might explain why the film is not titled “Glimpse of a Garden.”) There is something terribly moving about this biographical detail, which goes unmentioned in the documentary as well, because it suggests a generosity of soul — or, perhaps, more rightly, an insistence on life and self-affirmation — already evident in Ms. Menken’s images. Behind these delicate yet resilient, unmistakably feminized flowers, we intuit someone who could find beauty in the world, no matter how badly that world might have treated her. And not just find beauty, but also return it to the world, though on her own emphatic terms.

Ms. Kudlacek omits much: she never tells us whether Ms. Menken formally studied art (she did, including at the Art Students League); it’s even unclear if she and Mr. Maas had any children. The death of a child is mentioned almost in passing in the film, but in a published interview Mr. Anger, who lived with the couple for a short time, mentions visits from a son.

Still, salient details and observations emerge in the documentary, principally through interviews with the likes of the painter and filmmaker Alfred Leslie and especially the poet and photographer Gerard Malanga, who studied with Mr. Maas and whose tender recollections of Ms. Menken suggest that, while any biological children remain shrouded in mystery, there were loving surrogates nonetheless. Marie Menken’s garden bloomed, and not only on film.

.jpg)

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar