Blog o dobrim filmovima i video-spotovima.

somethingaboutsilence.wordpress.com/

It’s like another beginning, or another ending. Not that it

matters, really. There’s so much to say, and no way to say it. While the

audience is asleep, dead, and a door that had always been there is

finally opened. Holy Motors, white limousines, hundreds of ‘em, thinking

about their imminent extinction, while humans keep on killing

themselves on the streets. What is life, anyway? What’s that thing you

call home, when you come back at night? Coming back from what? I miss

forests. It’s just when the blood comes out that you can tell the

difference between a real experience and a virtual one. Or, at least, a

homicide is a good way to catch a cold. Or you can kill yourself, twice.

Or another time more, it depends on how much time you have left. You

can find beauty in cemeteries’ flowers, or in a sewer. Until you realize

that it’s all in the act. Remember the time when people would enjoy

those jumpy, scratched images, bouncing in an eternal loop, always the

same? Me neither.

After shaking, or shocking, the audience with Kynodontas (Dogtooth, 2009), Giorgos Lanthimos continues his path with Alpeis, which shares many elements with the former. Lanthimos is mostly interested in observing his characters interacting in social environments which go by their own rules. In Kynodontas, similarly to Arturo Ripstein’s El Castillo de la Pureza, the parents, in an attempt to preserve their children’s purity, keep them confined in their house. The three teenagers have never been in contact with the outer world, and live in the twisted reality made up by their parents, with their own vocabulary and their own beliefs. But we know what reality is, we understand the rules set by the parents, we can still distinguish fantasy from reality. But in Alpeis, it really is hard to tell what is real and what not. A group of four people reenact the lives of recently dead persons, interacting with their relatives, to make their mourn more acceptable. Them, too, have to obey the rules. But are these rules coming from themselves or are they dictated by others? Are all of the scenes we see just an act, or there are still some true feelings? Just like in Kynodontas, words are emptied from their meaning. The characters talk for the entire movie, but it’s possible that every word they said didn’t really mean anything. We found ourselves lost because, as the scenes go by, we can’t even tell what’s the real nature beneath the relationship between the four main characters. Maybe it’s not even our problem, maybe even them can’t tell where the line between reality and act is drawn.

Lanthimos digs in the depth of human interactions by twisting the meaning of what is being said on screen. His works recall the theatre of the absurd, mostly the works of Harold Pinter and, in certain aspects those of Samuel Beckett, because they put human nature on a dissecting table and use communication itself as a scalpel, bringing out what is buried deep down. Neither Kynodontas nor Alpeis are black comedies, as they are often been labeled. There are elements of black humor, but they are inscribed in an absurd environment that makes them normal. We too have to follow the established rules to understand what is going on. And when you don’t follow the rules, terrible things happen. In Alpeis, violence is more psychological than physical, apart from a key scene, which anyway is nothing near the crudeness of the previous movie. By switching from the closed environment of Kynodontas, far easier to control, to the wide and incomprehensible one of Alpeis, Lanthimos’s style gets colder and more detached. Characters are often blurred, cut from the shot, isolated in vast rooms, left alone in all their fragility. The hand-held camera makes us feel like intruders, peeping on these people lives, often behind corners or half-closed doors. The cinematography is curated by Christos Voudouris, who previously worked with the greek master Alexis Damianos on his last masterpiece Iniohos. Voudoris relies on a pale palette and cold tones, thus increasing the feeling of inadequacy and sadness that permeates the interns. Aggeliki Papoulia and Arias Servetalis had already worked with Lanthimos (respectively on Kynodontas and Kinetta, the director’s first film), Ariane Labed starred on Attenberg, which Lanthimos produced among others, while Johnny Vekris is at his first performance here. Most of the film relies on Papoulia’s performance, and she already proved to be the perfect choice to portray the absurd normality of Lanthimos’ scripts. Her empty eyes that shows little to no emotion are the perfect mirror to her lost character, who hardly can distinguish what is real from what’s not. All the other characters, while getting less screen time, are fundamental as well and their interpretation is perfectly calibrated and leave the desire to know more about them, even though the little we already know could be all but true. Lanthimos quickly became one of the most discussed young filmmakers, but he already demonstrated that he knows what he wants and he knows how to deliver it. I haven’t seen his first film yet, but as you can read, I strongly view his last two movies as highly connected, both in style and purposes. While Kynodontas was maybe too indebted with El Castillo de la Pureza by Ripstein, Alpeis confirms the ability of Lanthimos, and leaves me anxious to know what he will come up next.

Daniele Ciprì, along with his long time companion Franco Maresco, has been an outcast of Italian cinema since the ‘80s. Due to the provocative vein of their works (Cinico Tv, Lo zio di Brooklyn, Totò che visse due volte), they’ve often been censored, but they quickly gained a cult following, and permanently marked Italian cinema with their particular visual style. È Stato il Figlio is Ciprì’s first movie directed without Maresco, after the pair split a few years ago. After being the cinematographer for the latest films of Ascanio Celestini and Marco Bellocchio, he decided to direct a movie inspired by the homonymous book written by Roberto Alajmo, based on a true story.

Rather than being rooted in reality, È Stato il Figlio is more of a twisted fairytale, an old postcard coming to life where, behind the grotesque façade, lies the absurdity of life. A story within a story, told by a man who spends his days sitting at the post office, while hundreds of people swarm around him. He talks to nobody in particular, but he eventually gathers quite an audience, all agape while listening to the story told by this almost catatonic man. The Ciraulo family is numerous, but broke: only Nicola, the father, earns some money by working by selling scrap iron from disused ships. One day, her youngest daughter is accidentally killed by a stray bullet shot by Mafia hitmen. The pain is unbearable, but they soon discover that a compensation for mafia victims can be asked. A large quantity of money is promised, and the family starts spending it even before receiving it. The plot is as simple as that, but the movie’s power lies in how the story is told.

Ciprì didn’t abandon the style that characterized his earlier works with Maresco, but has evolved, exploring new paths but maintaining numerous links with his personal visual poetry. The Grotesque Body has always been a trademark of the duo: here, it’s still present, even if in a less extreme shape. All characters have a strong physical presence, accentuated by camera work and cinematography (just compare the segments that take place “in real life” and the ones regarding the Ciraulo family). Bodies are exposed and exploited, but mostly for a humorous purpose, covering the real horror that lies beneath. Except for a wonderful scene in which Nicola drives his newly bought car while all kinds of stereotypical elements regarding Sicily flies on the background, in a grotesque orgy of summer postcards horror, there are no fantastical elements in the movie. Yet, the atmosphere is that of a fairytale, with its own mythology and its recurring elements: the old man dressed in black who stand at the center of the courtyard all day, abandoned cars that lies around like skeletons, a money lender who’s actually two different and, apparently, interchangeable people, a lawyer that looks like a vulture, and also obese men, dwarves and so on. It’s a parade of characters that almost came out from a hall of mirrors of some cheap amusement park, but this doesn’t result in a cynical laugh, but rather in a greater distance between tale and reality.

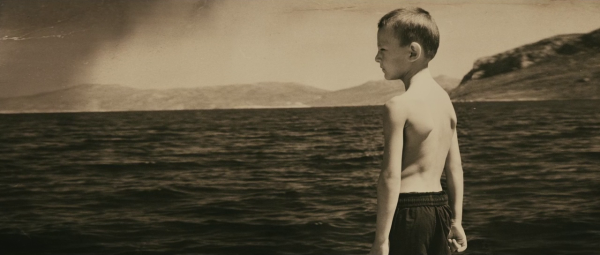

Far from the rigorous self-imposed style of Cinico Tv and his derivatives, here Ciprì adopt a far more versatile style, placing the camera in the most various places, moving it freely and thus making suggestive takes that widely portrays not only the actors but the places as well, creating a Sicily so imaginative that seems real (in fact, the film wasn’t shot in Sicily at all). The cinematography is superb: Ciprì paints the scenes with subtle but definite sepia tones, increasing the feeling that what are we watching is nothing more than an old yellowed photograph that came to life.

The actors do a tremendous job: Toni Servillo on top of all, but also Alfredo Castro, who manages to leave his mark, despite the few minutes he appears on the screen, and each other component of the cast. The acting is always over the top, exaggerate and made unique by the use of dialect that makes every sentence burst as soon as its spoke.

Ciprì has shown that not only he’s able to achieve success even if directing alone, but also proved to be a complete filmmaker, with his own style that stands out in the crowd of mediocre products of today’s Italian cinema.

I’m not a hardcore Kim Ki-duk fan, so I can’t really compare his last effort to his previous works, but even if considered alone, Pieta is far from being the masterpiece that everyone is talking about.

The major problem is in the plot structure. Almost two thirds of the movie are spent repeating the same scene over and over again. So we see the main character going around, doing his job, which mainly consists in smashing indebted worker’s limbs to collect the money from their health insurance. It’s an interesting starting point, but as the film goes on, it becomes tedious after plenty of slammed doors, random kicks and slaps and characters shouting at each other. From what I’ve seen, repetitiveness is common in Ki-duk’s works, but here rather than being significant, it just seems a tired attempt to hide the absence of a real plot. The sudden appearance of a woman who claims to be the protagonist’s mother, which would be the main plot, doesn’t really change the film’s pace.

Certain Ki-duk’s movies became famous for being extreme in many ways. A film like Seom (The Isle, 2000) doesn’t offer gratuitous violence, but extreme acts portrayed by extreme characters. Even if highly disturbing, violence mirrored the character’s twisted approach to reality, like a Greek tragedy. But this is not the case. Despite what I read, there’s nothing here that can even be compared to Ki-duk’s earlier movies. Violence is just suggested, and never takes place on screen, apart from some kicks and slaps, but nothing that won’t make you sleep at night. This is not necessarily a weakness, but the director’s choice isn’t even justified by a precise ideological approach, such as Haneke’s in Funny Games, just to name one. While in Seom the characters showed their inner self through their extreme acts rather than words, here they appear empty and their actions seem mostly random.

Another major weakness is in the dialogues. One of the strongest features of Ki-duk’s style was the capacity to unfold the plot without the need of dialogues. Here, not only characters talk all the time, but what they say is useless, blatant. They point out the obvious and, in the final scenes, even explain the plot twist, that had been already shown a few scenes earlier. The idea behind the film isn’t bad, but the sloppy way in which dialogues are used makes it seem almost idiotic. Not only the plot is explained, but even the ideological interpretation, if there is one, is highly anticipated by the same characters.

On the technical aspect, it seems that Ki-duk deliberately chose to give the movie a raw look, with shaky handheld camera, unnecessary zooms, and a general indifference for composition. The style is coherent with the plot, but a greater attention to details would have been better. I consider Pieta a missed opportunity. The plot, while interesting, isn’t really developed. The movie is repetitive after a few scenes, dialogues are redundant, and the general atmosphere seems just a bland imitation of his previous style. But I don’t think Ki-duk isn’t capable of doing better, Pieta could and should have been better.

Despite being one of the most important filmmakers around, the last works of William Friedkin didn’t get the attention they deserve. Both Bug and Killer Joe are little masterpieces, and the proof that Friedkin, in comparison with other directors, still has something to say, and knows how to say it. Thanks to the collaboration with playwright Tracy Letts, who wrote both the stage versions on which the movies mentioned before are based and the screenplays, Friedkin has adopted a different style from his previous works. Nothing really innovative or experimental, but rather the opposite. The style closely follows the narrative aspects, leaving almost nothing to what isn’t useful to the plot. But while in Bug the theatrical origin was evident, both in the number of the actors and the single location, in Killer Joe Friedkin chooses a broader approach, where each of the numerous characters is perfectly delineated in his own way. Apart from the number of characters, it’s usually the low number of locations that identifies a movie that is based on a stage play. Killer Joe, instead, develops its plot within a wide variety of places, and each one successfully portrays the exaggerated white trash, hillbilly environment in which the story takes place.

Tracy Letts, although American, is often considered part of In-Yer-Face Theatre, which comprehend the most controversial stage plays produced in England during the ‘90s, along with acclaimed playwrights such as Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill and Anthony Neilson. Killer Joe was his first play, written in 1993 and generally acclaimed, despite being one of the most violent and controversial plays ever staged. Despite ten years have passed, it still has that raw strength and that gritty humor that makes it work so perfectly. The large amount of violence, both in actions and dialogues, is taken to the extreme. Each character seems like a cartoon version, a parody of himself. But let’s be clear, despite being openly over-the-top, the story is still dead serious. There’s no space for post-modern irony: violence isn’t desensitized by itself. For example, in any movie by Tarantino, violence is almost portrayed as funny, it never shake the audience because it rarely serves a purpose, rather than being there for the glorification of violence itself. Here, the shock doesn’t come from violence, but within the ease with which violence is accepted by the characters, that don’t seem to have any kind of morals. There’s no positive figure in this dark barroom tale, a mixture of Southern Gothic, Williams and Faulkner, with lots of dirt, mud and blood more.

As expected, much of the action takes place in the dialogues, perfectly crafted and fast-paced, filled with subtle wit and black humor. The action scenes aren’t missing, but they’re not in the same vein as those from The French Connection or else. Here, everything is projected into a domestic environment, causing the bursts of violence to be even more disturbing. The highlight of the film is the surprising Matthew McConaughey, mostly known for being casted in the majority of last years’ romantic comedies. The creepiness of the film is mostly due to his interpretation of Killer Joe, so convincing that the part seems written especially for him. But everything works perfect also because every other actor involved gives his best. It’s rare that everyone involved fits their role in such way. Emile Hirsch, famous for his role in Into the Wild (2007), Juno Temple, Thomas Haden Curch, Gina Gershon and even the minor characters who gets few minutes on the screen: they all do a wonderful job. It’s difficult to examine them individually though, because it’s in the interactions between characters that the power of the screenplay relies.

It may sound strange, but Killer Joe functions as a twisted morality play. If it weren’t so realistic, despite the over the tone characterization, I’d almost say it shares some elements with the theatre of absurd: the way words lose their significance, the surreal situations that result, the final climax that bursts in a highly disturbing and distorted scene, all elements that reminds me of Harold Pinter‘s theatre. And after all, it’s not a coincidence if Friedkin directed Pinter’s The Birthday Party at the beginning of his career. But remember that all this elements are mixed within the thriller genre and supported by a coherent and classic plot.

Critics didn’t pay attention to Friedkin’s last movies, mostly because they’re still thinking about The Exorcist and The French Connection. Well, if he moved on, so should they. The collaboration with Tracy Letts resulted in two great movies, which Friedkin successfully transposed without losing nothing of the stage versions’ strengths, and also creating a product that is stylistically perfect in its simplicity, in comparison with today’s American cinema, which mostly relies on fast editing and deafening audio effects, cheap tricks that divert the viewer’s attention from the lack of cleverness behind the camera. This is not the case. And by the way, you’ll never look at fried chicken the same way again.

Although I recognize the directorial skills of Jacques Audiard, there still isn’t any of his film that I really liked. It always seems to me that something’s missing, despite his great capacity behind the camera. De Rouille et D’Os is not a bad film, don’t get me wrong. But it’s one of those cases where a highly illogical and unmotivated ending ruins the entire film. I usually don’t care for coherent plots, nor I think that the narrative aspects is the most important thing in the organism of a movie. But Audiard’s film isn’t experimental, such as Post Tenebras Lux for example. In fact, it maintains a classic structure, and the plot is undoubtedly its main feature, so ignoring its fallacies would be a mistake. For the sake of your cinematic experience I won’t actually talk about the ending in detail, but I need to specify from where my disappointment comes from. As I said, the movie is not a bad one, in fact it’s quite the opposite. The main characters are portrayed by two of the best actors around, the screenplay is based on a more than solid source, a great director. All of this works fine, until the last ten minutes, but I won’t say more.

The film is loosely based on the short story collection Rust and Bone, by Canadian author Craig Davidson. Audiard takes just some elements from two of the many stories in the book and then develops his own story, so not much of Davidson’s work is present in the movie. There’s no real reason to confront the two products, since they share so little, but I think it’s still interesting to analyze the two. The book by Davidson is probably one of the best contemporary short fiction book that came out in these years. His writing is raw and direct. Most of the characters are losers, rejects trapped in a nihilist world, where violence, both physical and psychological is the only way to communicate. Audiard takes a different approach. The atmosphere never gets too dark or nihilistic, and the tones are way lighter than the book, but some sort of crudeness remains, especially in the first part of the film. In Audiard there’s room for love, even if tormented and complicated, in Davidson there’s no such thing as love.

Matthias Schoenaerts and Marion Cotillard are at the center of the film and they do a wonderful job together. The alchemy that arises between two anti-social characters is interesting and well developed: a self-destructing relationship among two people that don’t intend to change their personality, even for the sake of love.

Ali has a child, but no home. He seems to have no empathy for anyone, but not in a cruel or cynical way. He’s just incapable of caring about other people’s feelings. His life is built on violence, and with violence he can afford to survives, first as a bouncer at a club, where he meets Stéphanie, and later as a street fighter. Schoenaerst already proved to be a great actor in Rundskop (2011), in which he portrayed a similar character. He prefers to act with his body rather than his face, and despite his enormous, heavy physique, he manages to transmit the sensitive aspects of his character as well. Stéphanie remains mutilated after an incident, but she doesn’t want any help by other people, she wants to be self-sufficient in all the aspects of her life. Cotillard doesn’t need presentations, being internationally recognize by now as one of the most talented actresses around. Here she gives one of her best performances, thanks to a charismatic character that allows her to exploit her capacities.

The camera stays close to the characters, but never too much. There’s always room to back up a little and see things from a more detached point of view. It’s a film about bodies and the flesh and blood inside them. More than emotions or feelings, it’s the corporality the thing on which the camera focuses. Like animals, Ali and Stéphanie communicate better with their actions rather than with words. There’s more communication in a sex scene than in dialogues. Problems arise when there’s the attempt to rationalize their behavior. Despite the many laughs of the audience during the scenes in which the two characters discuss about their sexual relationship (I still don’t know who to blame, why full grown adults should always laugh at anything sexual portrayed on the screen?), it’s here that resides the tragedy.

Despite the great confidence with which Audiard films this story, the natural alchemy between two great actors and the well written screenplay, there is some uncertainties as the story progress. While the first part remains solid, the plot begins to feel repetitive after some time, while other aspects that are left behind could have been better explored, such as the relationship between Ali and his son, that gets lots of attention in the first half of the film but is later almost forgotten for the remaining time, just to pop up later in the ending. As said before, the final is the weakest part of the movie. It really seems hurried and badly put together and manages to ruin everything that was shown before, being it incoherent and not in the same vein as the rest of the movie. A missed chance, Audiard should have dared more, but he confirms his talent nonetheless, and still remains one of the most interesting French filmmakers.

Post Tenebras Lux sure is a strange beast. Nobody liked it, neither the critics nor the public. And I guess they weren’t supposed to. I haven’t quite made my mind up yet. Surely while watching it you’ll find yourself thinking “what the fuck” over and over again, but maybe, weeks later on, thinking about it, you’ll start seeing the overall picture, and feel how strong it is.

It’s difficult talking about this without spoiling the atmosphere. Also, there is no actual plot. Or better, there are some hints along the way, but nothing really coherent can be told.

The movie is strange not only on its narrative side but in its aesthetics as well. The format chosen is surely not popular nowadays (aspect ratio is 1,37:1), and the image itself is anything but conventional. While the center of the shot is clear and definite, the edges of the image are blurry, refracted, sometimes doubled. This expedient gives the entire film a strange atmosphere, dark, foggy, in a certain way evil. As in, even when what you are seeing is just a nice little girl running around in a field, you can feel that something is not right. And that feeling permeates every second of the movie. The scenes alternate between the what you can call normal ones and the real weird ones, which, even if I’d like to, I won’t talk about, to avoid spoiling the surprise. After some time even the normal scenes won’t seem so normal anymore. The power of Post Tenebras Lux is in its aggressiveness towards the viewers. But let’s be clear, I don’t think Reygadas deliberately wanted to annoy or attack the audience. But I perceived the film as some sort of thick venomous cloud, that surrounds you, hot and suffocating. The exasperated use of wide-angles deforms everything, like in a twisted mirror chamber, for the entire duration of the film, and the effect soon becomes asphyxiating. Some features of Reygadas’ previous works are still here, but mashed up and twisted in a nightmarish mixture. An emblematic scene is the one that takes place in a sauna/sex club, where red, deformed, sweating bodies are aligned along the walls like cattle in a slaughterhouse. The highly hallucinatory atmosphere is rendered weirder since the grotesque bodies performing like animals speak in a polite and gentle way. And this is just one of the most normal scenes.

Nobody can deny that this is by far Reygadas’ most personal work. The choice of using his own children to act in the movie is not casual. The result is a sort of dark amateur home movie, due to its closeness to the characters and the intimate approach. On the background, many stories unfold, some of them more developed, others just hinted. The contrast between rich and poor, represented by the protagonists’ family and the other villagers, workers etc. might look like the main plot, but it really isn’t. Reygadas already treated this topic with the wonderful Batalla en el Cielo. Here we have something more subtle. An impending apocalypse that doesn’t spare nobody and manifests itself in numerous ways and involves many different characters.

Sure it’s a weird movie, but I prefer imperfect experimental movies over conventional already seen ones. Reygadas is slowly departing from his initial influences (mainly Tarkovskij among the others) to search for something different. Post Tenebras Lux itself looks like a work in progress, a film that searches for its own meaning, if there is one. I don’t ask for meaning nor I pretend it. This film won’t leave you indifferent, and that’s enough for me.

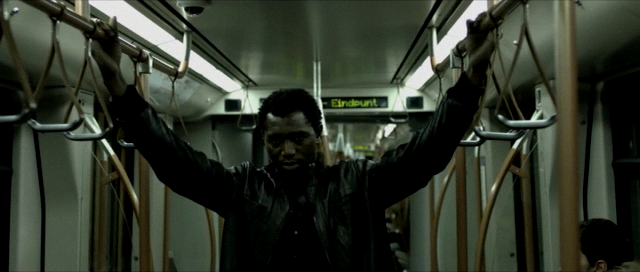

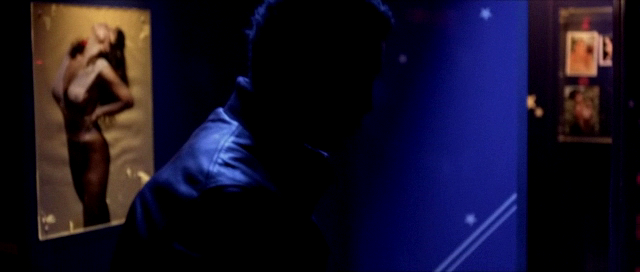

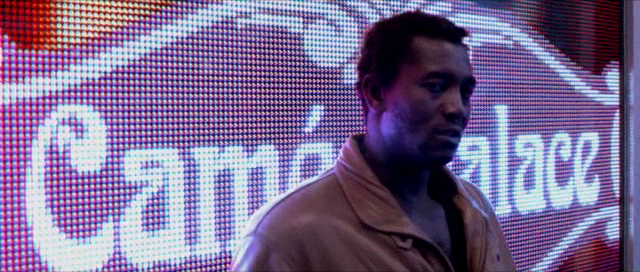

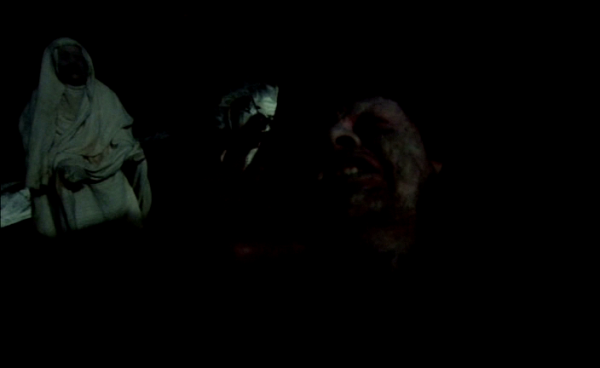

To talk about politics by making an horror film, or to talk about horror by making a political film. Pablo Larraín does both, with Tony Manero. 1978, Chile is under the dictatorship of Pinochet for the past five years. Soldiers patrols the streets day and night. Protesting against the regime leads to torture and death. Raúl Peralta (Alfredo Castro) doesn’t seem to care about this. In fact, he doesn’t care about anything around him. Except for Tony Manero. He’s obsessed with Saturday Night Fever, or better yet, with its lead character. He always carries around his white suit, he’s obsessed by its accuracy (one or two buttons?).

His day is divided between his visits to the local cinema, where he contemplates with astonished eyes the movie, repeating the lines that he has learned by heart, and the rehearsals for his own version of Saturday Night Fever, performed along with three other persons (a young woman, with whom he has some sort of relationship, her daughter and a young political activist). Always expressionless, his eyes become alive only when in front of the cinema screen. Apart from that, he has no interest whatsoever in other people’s lives. He helps an old lady who has been robbed on the street, just to smash her head a few moments later and steal her tv set. He brutally murders the owners of the cinema because they replaced Saturday Night Fever with Grease, and eventually to steal the film as well, to look at the single frames, alone in his room. Even when committing murders, there’s no joy or satisfaction in his eyes. His crimes doesn’t fulfill any urge or desire, just his material needs. He lives to be the Chilean Tony Manero. All his actions leads toward a TV program, in which Tony Manero’s doubles will perform. “What do you do for a living?” asks the TV presenter to Raúl. “This”, he answers.

Even if Tony Manero doesn’t appear as an explicit political movie, or at least not as explicit as the next Larrain movie, Post Mortem, the parallel between its protagonist and the regime in which he lives become clearer as the movie progresses. Raúl Peralta is the product of the Pinochet era, with its mindless violence, his isolation are the mirror of the ill society in which he lives. I always choose carefully the stills that accompany what I write, I think images have a great deal when talking about movies. I don’t pick random frames, but I try to capture moments that are beautiful enough to survive outside the film itself. At the same time, I try to diversify the subject of the stills, to have a wider range of images.

This time, the choice was very limited. Alfredo Castro, who also co-wrote the screenplay, dominates the movie. His face and body fills the frame in a claustrophobic way. The hand-held camera follows him everywhere, rarely focusing on other characters. A grainy look, obtained by shooting on 16mm and then blowing up to 35mm, often out of focus contributes to increase the squalor that permeates the movie. The sex scenes are empty, cold, depressing. Raúl doesn’t enjoy sex with his companion. He seems to lust after her daughter, but is incapable of having sex with her. Despite living in misery, he lives in his own world, where a football with broken glass glued on is a disco ball to dance under. This mix of decay and horror, both political and psychological, creates a nightmarish atmosphere that sticks to the viewer long after the movie ended.

Alfredo Castro is plain superb. With few lines of dialogues and even less facial expressions, his portrayal of a serial killer is one of the most convincing ever seen. He isn’t only monstrous, but almost makes the viewer feel guilty and dirty himself. Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer comes immediately to mind, but it’s quickly clear that Larraín’s intention isn’t just to tell a story, but to shake his audience as well. The rest of the cast is convincing as well but, as one might expect, is obscured by Castro’s presence. It’s not a coincidence after all: Larraín worked with Castro since his first film, Fuga (2006) and the collaboration between the two continues through Post Mortem (2010) and No (2012).

While most of todays political movies are mostly anachronistic, nostalgic or just useless pseudo pamphlets without energy, Tony Manero, along with Post Mortem, is one of the strongest and significant movies in recent years without even being too explicit about it. But considering it only under a political profile would be reductive. Pablo Larraín is one of the most talented filmmakers around. His political cinema is anything but sterile. Choosing not to focus entirely on political themes, but intertwining them with well-developed characters is the key to create a powerful story that also educates viewers on a portion of history that is too often forgotten.

While most of todays political movies are mostly anachronistic, nostalgic or just useless pseudo pamphlets without energy, Tony Manero, along with Post Mortem, is one of the strongest and significant movies in recent years without even being too explicit about it. But considering it only under a political profile would be reductive. Pablo Larraín is one of the most talented filmmakers around. His political cinema is anything but sterile. Choosing not to focus entirely on political themes, but intertwining them with well-developed characters is the key to create a powerful story that also educates viewers on a portion of history that is too often forgotten.

The fifth season is the one that lasts for a year. It’s the perpetual winter. When the plants refuse to grow and even the colours fade away.

The last chapter of an ideal trilogy about the relationship between man and nature, La Cinquiéme Saison is a great improvement in comparison with the previous movies by Peter Brosens and Jessica Woodworth. Khadak (2006), shot in Mongolia, and Altiplano (2009), shot in the Andes, suffered from an uncertain style, torn between an anthropological approach, a traditional narrative and a contemplative style. These three elements weren’t mixed well together, and the result was confusing, redundant, without direction. Maybe it’s because La Cinquiéme Saison has been shot in their country of origin, Belgium, that it appears so firm, rigorous. The minimalist approach allows the directors to focus both on the visual and the narrative aspect, creating a visual masterpiece with enormous visual strength and a plot that, despite the abused theme of nature versus man, delivers the directors’ opinion without being blatant or rhetoric, as was the case with the previous films.

What at first appears to be a joyful celebration of the end of winter in an isolated village will soon turn into an apocalyptic nightmare. The puppet that represents winter, made out of twigs, won’t catch fire during the rite. The purgatory fire that will dispel winter to welcome spring can’t be set. It’s just the beginning of the end. Bees disappears, seeds won’t grow, cows won’t give milk anymore. Season after season, while hope slowly fades away, as snow keeps falling during summer and insects are the only edible thing left. What is most terrifying is what the viewer can’t see. Why everyone remains in the village? Why everyone calmly accept their doomed faith? It’s hinted that, probably, outside of the village, the situation is even worse. Worse than what are we seeing. The disturbing stillness that permeates the village will not last long.

Who’s the protagonist, the people or nature itself? Brosens and Woodworth focus on both. There’s Alice (Aurélia Poirier) and Thomas (Django Schrevens), two teenagers, maybe in love, or maybe not. There’s Pol (Sam Louwyck), the itinerant beekeeper and his handicapped son Octave (Gill Vancompernolle), and there’s the rest of the families and individuals that compose the reclusive village that once seemed to be idyllic. Apparently, the camera follows them, but it often continues its path, leaving the humans out of the picture, to follow the dying nature surrounding them. The visual richness is also given by the supremacy of the camera itself, that shoots from a wide variety of angles, as if able to catch every moment given. The characters are often seen from a high angle, resulting in a crushing perspective that makes them even more fragile.

The choice of limiting the dialogues to the essential helps creating a mesmerizing atmosphere, where every scene turns into a tableaux, and despite the pale palette chosen, the colours burst on the screen. The atmosphere resembles those of Béla Tarr’s movies, especially his last, The Turin Horse. The sense of impending doom, men forced to their limits, the crude consequences of human nature. Behind the stunning aesthetics, there’s also a strong plot, that proceeds on his character’s feelings rather than a classical narrative plot. We see results, not causes. Where most critics see a lack of narrative structure, I see a way to challenge the viewer, bound to partake in the stream of events. Not that it’s hard to follow what happens on the screen, it’s just that, for once, the viewer is not considered stupid. There are no useless dialogues that describes what we already have seen, or that explain what the movie should mean, a thing that happened instead on the previous works of Brosens and Woodworth. Music isn’t used as a way to describe what is happening on the screen, but participate along with the other elements to create scenes of high impact.

One of my personal favourites of the entire year, if not of all time, La Cinquiéme Saison is a little masterpiece, achieved after uncertain works that, anyhow, hinted the potential of this Belgian couple, that finally seems to have found his balance.

I won’t bother repeating myself on how Seidl operates, since the style remains unchanged since Liebe (and from all of his other films), so those who aren’t familiar with Seidl’s works can read my previous review.

The second chapter of the Paradies Trilogy, Glaube (Faith) gained more attention than the previous one, Love, mostly because of the journalists’ morbid hunger for supposed scandals. Despite being way less controversial than Liebe, Glaube has been labelled as blasphemous and disrespectful towards Catholicism, mostly because of the much debated scene in which Anna masturbates with a crucifix. Fact is, the scene is probably one of the least scandalous shot by Seidl. There’s rather a sense of shyness in it, a delicate moment where faith and love meet.

Considering Seidl a provocative auter is improper, if not overall wrong. He’s crude, relentless, not compliant, but he doesn’t aim at shocking the audience, nor does he want to create sterile polemics. Seidl already dealt with religion, and Catholicism in particular: Jesus, Du Weisst, shot by Seidl in 2003, is a portrait of six different people, six different approaches to religion, but there’s no trace of irony in it. Despite sometimes being almost insane (at least to a laic viewer), each one of the person portrayed by Seidl is treated with deep seriousness. Glaube doesn’t share the violent anti-clerical vein that characterizes the works of Luis Buñuel, Marco Ferreri or Ciprì and Maresco, just to name a few, and this is because Glaube doesn’t aim to be an anti-clerical film. The extreme way in which Anna (Maria Hofstätter, already present in Seidl’s first feature film Hundstage) lives her Catholicism is just a part of her being, and it’s not condemned or ridiculized by Seidl, just as the search of Theresa for a sexual adventure in Liebe wasn’t judged or condemned.

The main focus of the film is the disintegration of the relationship between Anna and her husband Nabil, an Egyptian Muslim confined to a wheelchair which returns suddenly after years of absence and the clash between their beliefs, which are not so different after all. The camera follows Anna as she spends her holidays, during which she tries to convert as many people as possible, especially immigrants, to save themselves and to save Austria. If in the previous film the skin of Theresa was red because of the sunburns, here the skin of her sister Anna is wounded by the self-inflicted lashes on her back. Through pain and self-humiliation she expresses her love for Jesus. Her group of prayer reunites at her house and stares right into the camera, composing a traditional Seidl tableau, while chanting and praying, creating a strong sequence that startles the audience.

The efforts of Maria, when she tries to convince people to pray in front of a statue of the Virgin Mary, can have hilarious consequences, such as the sequence involving René Rupnik, (a familiar face, since Seidl shot an entire documentary on him, titled Der Busenfreund), or tragic ones, such as the encounter with a russian immigrant that soaks her desperation in alcohol. The way in which the scenes are perceived depends, as usual, on the audience. As I said before, one of the many pleasures of seeing a Seidl movie at the cinema is checking on the audience reactions. When I went to see Glaube there were few people present, but there has been numerous laughs at certain scenes, especially those involving religious debates or Anna’s self-inflicted punishment. The interesting thing is that the film is not meant to be funny at all, or, to be more precise, it isn’t structured as a mix of comedy and drama. Seidl himself said that:

this reaction says a lot about audience members who no longer take religion very seriously, but this is not my case. I was brought up in the strict Catholic tradition and I conducted enough research and interviews with fervent believers when I made Jesus You Know to be able to tell you that this is not the case for a lot of people. [source]Despite the rigorous way in which Seidl organizes the shots, always a visual pleasure, the film itself could’ve been way better. The scenes are way too repetitive and similar to each other and the story never fully develops. These are not necessarily bad features, but compared to Liebe, Glaube isn’t fresh enough, nor inspired as the first. The tension between Anna and Nabil remains superficial and sometimes a bit childish, but nevertheless achieve numerous peaks of physical and psychological cruelty. Even the dialogues are often blatant and avoidable, mostly when they deal with problematic issues such as religious conflicts between different beliefs or the way immigrants are treated. These topics have already been explored by Seidl in his previous works with better and more incisive results, and also by other, maybe lesser known, directors such as Christoph Schlingensief.

Try to forget all the media fuss while you watch Paradies: Glaube, because, despite its flaws, it’s still a stimulating and intelligent experience, which gains even more beauty if seen in its entirety along with the other two chapters of the trilogy, a terrifying portrait of our contemporary world, but in which we can still find traces of love, faith and hope.

Colder than his fellow citizen Haneke, formal as Greenaway, relentless like Herzog, Ulrich Seidl is one of the most interesting contemporary filmmakers. After exploring/exploiting the thin line between documentary and fiction, creating caustic works like Tierische Liebe, Good News and Models, Seidl directed his first feature film in 2001, Hundstage, followed in 2007 by Import/Export. Paradies should have been a massive 5 hours and a half film, on which Seidl worked for over 4 years and shot 80 hours and more of material. Seidl realized that the three intertwined stories worked better as a standalone, so the film is now a trilogy, each film about a woman, each one searching for a way to fulfill her dreams and longings. Liebe (Love), about Theresa, and her sex holiday in Kenya, Glaube (Faith), about Anna Maria, Theresa’s sister, and her catholic mission of conversion in Vienna, and Hoffnung (Hope), about Theresa’s daughter, Melanie, and her vacation at a diet camp for adolescents.

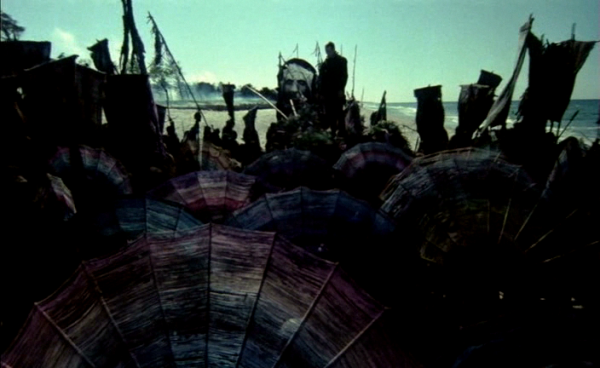

Paradies: Liebe, the first chapter presented at Cannes 2012, follows the trademark style of Seidl’s previous works, but it still maintains a rare freshness. Set on the beaches of Kenya, we voyeuristically follow Theresa, and her search for a male companion, a “beach boy”, among the natives, after years of disappointments in her love life. She’s not the only one, of course. They’re called “sugar mamas”, white middle-aged women from all over the world, each one trying to get a piece of heaven.

Margarete Tiesel, who portrays Theresa, is far away from the western standards of beauty: an overweight women in her fifties. In the mainstream circuit, overweight people are often used as ludicrous gimmick, or just seen as something to loathe. But here we just see a woman being what she is. Seidl doesn’t have a problem in showing her body to us. Real sex scenes that almost mirrors the ones of Reygada’s Batalla en el Cielo, are numerous. Theresa’s skin is marked by tan lines, and the contrast between the pale zones and the lobster red one create a sort of tragic ridiculousness, her desperate attempt to gain some satisfaction from the young boys who are only interested in her money. Her naivety seems more like a façade, but still she wanders, committing the same mistakes over and over.

But there’s no judgement in Seidl’s eye, it’s just that the camera spares nobody. We see masses of pale, flaccid skin, stranded on the beach like dying whales (a rembrance of Hundstage) trying to get a tan, while groups of Kenyans watch right into the camera (Seidl’s tableaux are his trademark since his first documentary), separated from the tourists by ropes, and armed soldiers that patrols the entire beach. Everything can be bought in Kenya. Not that this doesn’t happen in the rest of the world. But in the film, there’s no hypocrisy about it, except for the prudery of Theresa, being her first time. Her friends are already inside the mechanism, and they see no real problem in renting a young boy and giving him as a gift to Theresa, pointing out that “he’s all yours, from head to cock”. One of the longest sequence in the movie, the four women abuse in every way of the young beach boy, still he keeps smiling, he knows the rules. A squalid show indeed, but I remember people laughing during this scene. Actually, there were many laughs throughout the entire movie, I still don’t know if they were true laughs, or just embarrassed ones. Not that Seidl, doesn’t insert elements of comedy. Probably, the absence of a true point of view, due to Seidl impartiality to the events portrayed on screen (not to be confounded with indifference) led each viewer to feel the movie’s atmosphere as he likes. Still, I firmly believe that if the scene portrayed four obese middle-aged white men abusing a young black girl, nobody would have laughed. I guess that’s one of the many strengths of Seidl’s way of making movies: the ability to show the true nature of both his characters and his viewers.

Seidl starts from an accurate script, that defines the situation and the location, but no dialogues are writer. The scene comes alive only when the actors, both professional and non, act the situation, identifying with the situation, portraying their true emotions to the scene. Seidl and Margarete Tiesel spent an entire year in Kenya only to find the right actors among the natives, the ones that really connected with her and that were able to appear authentic on camera. Seidl’s film crew has almost remained the same from his first work, from the casting director to the camera operator, and that’s one of the reasons why he is one of the few that have successfully maintained his style without making it trite but instead evolving in new directions. The entire film is shot on location, and no additional music was used, other than the diegetic one. Along with one of the best openings I’ve ever seen, every shot is perfectly organized in geometrical composition (apart from the hand held shots that follows Theresa through the city). The entire movie is permeated by a brutal atmosphere: a world where everybody struggles to survive, someone physically, someone psychologically. A reality that is not far from ours.

(All the

(All the

Everybody knows how most horror films work: the first twenty minutes or more are dedicated to present the characters, show their strengths and weaknesses, which will probably come up later in the movie. Unfortunately, most of the times, we don’t get characters, but stereotypes, so we are bound to watch the usual parade of teens getting high and fucking etcera etcera until they are massacred for our pleasure. So, the best you can wish with this kind of flicks is that the murders are actually funny or well done, otherwise there’ll never be any tension for the fate of random flat characters. Ghost stories can share this kind of incipit with slasher movies, or worse, they can have the usual protagonist who had a traumatic experience in the past and so on, lots of boring flashbacks and the result is always the same.

So, what happens when Ti West comes up with a brilliant movie, with real characters, a conventional yet well orchestrated plot and a perfect mix of comedy and horror? The Innkeepers. And nobody understands it, apparently. Like his previous work, The House of the Devil, despite having gathered many positive reviews, the usual comment is: nothing happens. The overexposure to plotless gorefest flicks may have led the large amount of the audience to think that if the girl doesn’t show her boobs for the entire flick, nor does she fuck with her male companion, then it’s all useless. Ti West cares about his characters, and doesn’t lose times telling what the characters should be, but he takes all the time needed to show them to us, through their actions, their dialogues, their faces.

Claire, an innkeeper of the Yankee Pedlar Inn, along with her friend Luke, is determined to discover the truth about the ghost of Madeleine O’Malley, which is said to haunt the hotel. Sara Paxton is just plain wonderful, as she portrays a shy but energetic girl, that doesn’t know what to do with her life, not having any ambition, but still tormenting herself on her immobility. We don’t have the usual voice-over that explains this to us, nor a flashback or dull dialogues. Claire often lowers her head when talking to others, she gets bored while talking with people that she doesn’t care about. She often act childish in many situations, walking awkwardly when disappointed, dragging her feet like a 5 year old brat. You get to know her in different ways, such as the long, and comically cute, scene where she takes out the trash, almost acting like a silent movie clown, or just by noticing how her nail polish is almost entirely peeled off. The other characters are well portrayed as well, but of course the focus is on Claire. Nonetheless, West choices on casting are always accurate, opting for good acting or strong screen presence. The character portayed by Pat Haley, even if not fully developed as Claire, is a good example of how West is able to exploit stereotypes, the geek type, but at the same time inflating them with meaning. So is the character of Kelly McGillis, that maybe lacks in depth but accomplishes her role of supporting character who is anyway deeply involved in the plot. The other roles, the mother and son (Alison Bartlett and Jake Ryan) and the old man (George Riddle), don’t get much screen time, but their strong appeal is enough to imprint them in the mind of the viewer. The puzzling face of the kid, as Claire tells him the story of the ghost that haunts the hotel, is weirdly scary, as is the old man in its entirety, how he talks and moves slowly, as if carrying something more than his age on his shoulders.

Ti West is able to extend the characterization throughout the entire movie, and not just in the beginning, thus creating a rare mix of comedy and horror. There’s an emblematic scene, at the beginning, where Luke shows a video to Claire, one of those Youtube clips where all of a sudden something pops on the screen and the volume goes loud, and jumping on the chair is inevitable. This is the most common way to scare the audience, but also the easiest. West doesn’t work this way. The slow camera movements accompany us on a tour of the hotel, perfectly neat and well lit, and yet we never know what could be around the corner, behind the door. Even if nothing happened yet, we tend to be suspicious. The lacks of guests, the disturbing silence are just the beginning. Later on, during the “recording sessions”, while Claire looks around for signals by the ghost, most of the atmosphere is created by sounds. We hear cries, whispers, an ethereal piano that plays in a broken way. The line between reality and hallucination is thin, and becomes blurrier as the film goes on. The unbearable tension will explode in the final climax, but before getting there, West has scattered hints and frights along the way. It’s mathematics. The cinematography, by Eliot Rockett, is vivid and simple, but plays numerous tricks in the basement scenes, and is overall functional to the general atmosphere. The music, originally composed by Jeff Grace, has a certain retrò taste, distinctive but not overwhelming, it accompanies most of the dialogues, contributing to increase the tension, and disappears when ambient sounds are more important, but it returns to accompany the more frantic scenes. A clever and dosed utilization that doesn’t highlights the obvious.

The film has a high number of meta elements, but not in an exposed way as Scream, nor it has any of the trite post-modern irony that infests the majority of contemporary products. West plays with clichés and stereotypes but succeeds in giving his own imprint on the overall product, and this is almost a miracle, if we look at the endless amount of crappy sequels, prequels, reboots and so on. Ti West loves horror, that’s clear, but apart from scaring us, he’s able to give us believable characters, especially female ones, the most mistreated category of horror movies, in such a natural way that makes me wonder what would he be able to achieve with other genres other than this. An independent movie, with few characters, one location and lots of atmosphere. This is enough for Ti West to make an excellent movie, a ghost story for the minimum wage.

Almost submerged in thick black water, blinded by the hazy sky and the stinging wind that makes the trees sing like flutes. The directorial debut of William Vega reflects the location where it was filmed, the luxurious shores of a great lake in Colombia, where every step is slowed by the mud. As the characters calmly perform their daily duties, so the camera quietly follows them, focusing both on people and nature. After an astonishing and genuinely disturbing opening, we get to know Alicia (Joghis Seudin Arias), a Colombian refugee who seeks asylum at her uncle’s guest house, after her village has been destroyed. We don’t get to know anything else, and even as the film goes on, nothing is explicitly told. Nevertheless, Vega succeeds in realizing a superb movie that works on different levels, and each one is as appealing as the others.

The love for the environment in which the film takes place is made clear by the harmony between camera and nature. Many minutes are dedicated to the lake’s water that never stops moving, where fishermen, like Alicia’s uncle Oscar (Julio César Roble), are forced in a state of precarious balance, the wood that slowly rots, the imposing vegetation, both beautiful and menacing, the rain that batters on the foil roof of the house that Alicia and Flora (Floralba Achicanoy), the housekeeper, are restructuring, waiting for the tourists to come. But the tourists may never come at all. A permeating sense of apocalyptic doom, like in Bela Tarr’s movies is perceivable for the entire time, intensified by the mysteriousness of the plot. We don’t really know why Alicia’s village has been destroyed, and why everybody treats her with diffidence. It’s difficult to understand the intentions of Oscar, his face carved in pain and patience, indecipherable. He spies on Alicia through a slit in the wall, as she changes clothes in the other room, with eyes that could be of affection or lust. Every time his hand touches her body it’s difficult to understand what drives that hand. The fear of rape is a constant menace that never actually take place under our eyes. So, when Alicia seeks comfort in her uncle’s room because of the drunk guests in the other rooms, we are both scared and curious about what will happen next, but our questions won’t be answered.

What could be a major plot point in other movies is just one of the many events that Alicia has to deal with: her love for Mirichi (David Fernando Guacas), the boy who saved her with his boat, an apparently lovable character who also has his own secrets, the fear that what happened to her village can happen again, or the sudden return of Freddy (Heraldo Romero), Oscar’s son, who seems to be the only one who knows what will happen next. The movie can also be read as a political statement, on the civil guerrilla that takes place in countries such as Colombia. A situation that, despite is commonness, is too often ignored by the western eye. Obviously, the director’s choice to make a movie that gives lots of questions but few answers can’t fully satisfy a viewer that might be interest in the social and political background of the story, but the crude impact of the film, especially the first and last sequence, should spur every viewer to know more about this not so distant country.

The cinematography, by Sofia Oggioni, gives its best in interiors, always in deep darkness, with warm candles that paint the characters in orange glimpses of light. The camera, despite its slow pace, keeps alive the attention by following the characters in their daily actions and their scarce dialogues. Apparently distant like in a documentary, the camera movements explain more than words, when focusing a few seconds more than expected on a glance in the characters’ eyes, or on the movements of their hands. Lazy viewers will find this troubling, to fully participate in the movie’s alchemy its required an observant eye, even though the temptation to let the pictures hypnotize yourself is strong. All the actors were at their first experience (at least from what can be told by the movie’s IMDb page, that lacks quite a lot of informations), but each one is perfect in their role, portrayed in a raw and realistic way.

Being a first film, La Sirga is an extremely powerful experience, the result of a four years project. Vega is a wise director, with a contemplative eye that never forgets to focus also on characters and their actions. He manages to develop a great story, showing much and telling almost nothing, and despite being too cryptic on certain aspects, La Sirga is one of the best movies of 2012.

(All the

(All the

Before seeing Julien Donkey-Boy, my only Dogme95 film had been Vinterberg’s Festen. I liked the film, but I was never truly impressed by the manifesto itself. The same founders never strictly followed all the restrictions, and quickly abandoned the movement. Nonetheless, restrictions are always useful if they led the filmmakers to search for new languages and solutions. Korine’s take on the manifesto is a little gem, visceral and utterly personal. Disliked by most (but it’s common with Korine’s work), the movie is similar yet different from his previous feature, Gummo. The grainy look of the film (shot on video, transferred onto 8mm and then blown up to 35mm) is almost palpable, as if it’s part of the characters, of the ambient. Figures are often out of focus, thin lines floating in fuzzy white surroundings. Fortunately, Korine doesn’t strictly follow the rules and, for example, uses extradiegetic music, creating mesmerizing scenes, such as the opening and closing ones: blurred ice-skaters, twirling in slow motion, smoothly but jerky at the same time, while opera accompanies the movements.

The acting is mostly improvised, but is supported by great actors such as Ewen Bremner, Chloe Sevigny and a superb Werner Herzog. I personally love Ewen Bremner, and it’s a shame that he’s only known for his role as Spud in Trainspotting (and it’s even more shameful that in the original theatrical play, he brilliantly performed in the main role as Renton, but in the movie this part was given to Ewan McGregor. Apparently you gotta choose a nice face over talent to sell a movie). Unfortunately, Bremner received few opportunities to show his talent, but his performances in Skin, based on Sarah Kane’s screenplay, or Mike Leigh’s masterpiece Naked are unforgettable. Here, he plays a schizophrenic adolescent, even though he seems the sanest of the bunch, since every character, in Korine’s tradition, is a freak or a lunatic. Herzog’s performance is astounding. If you know a little of the filmmaker’s background you can recognize a lot of references to his life, his works or his passions (he clearly quotes moments from his movie Aguirre, he mentions his love for ski jumping, just to name a few). He almost takes over Bremner character, with his hallucinated monologues, his dances, his patriarchal violence.

The acting is mostly improvised, but is supported by great actors such as Ewen Bremner, Chloe Sevigny and a superb Werner Herzog. I personally love Ewen Bremner, and it’s a shame that he’s only known for his role as Spud in Trainspotting (and it’s even more shameful that in the original theatrical play, he brilliantly performed in the main role as Renton, but in the movie this part was given to Ewan McGregor. Apparently you gotta choose a nice face over talent to sell a movie). Unfortunately, Bremner received few opportunities to show his talent, but his performances in Skin, based on Sarah Kane’s screenplay, or Mike Leigh’s masterpiece Naked are unforgettable. Here, he plays a schizophrenic adolescent, even though he seems the sanest of the bunch, since every character, in Korine’s tradition, is a freak or a lunatic. Herzog’s performance is astounding. If you know a little of the filmmaker’s background you can recognize a lot of references to his life, his works or his passions (he clearly quotes moments from his movie Aguirre, he mentions his love for ski jumping, just to name a few). He almost takes over Bremner character, with his hallucinated monologues, his dances, his patriarchal violence.

These interpretations are supported by all the non professional actors that take part in the film, such as Chrissy, a blind ice-skater girl, both in the movie and in real life, which gives us some of the best scenes and dialogues of the entire movie. The scenes shot in the church or in the school for blind people outweigh, in few minutes, entire movies with similar subjects or atmosphere (Lourdes, just to mention one). The naturalness with which the scenes are shot makes this nonsensical film look normal, only to impress the viewer on another level, by using schizophrenic editing and imaginative use of the mdp.

These interpretations are supported by all the non professional actors that take part in the film, such as Chrissy, a blind ice-skater girl, both in the movie and in real life, which gives us some of the best scenes and dialogues of the entire movie. The scenes shot in the church or in the school for blind people outweigh, in few minutes, entire movies with similar subjects or atmosphere (Lourdes, just to mention one). The naturalness with which the scenes are shot makes this nonsensical film look normal, only to impress the viewer on another level, by using schizophrenic editing and imaginative use of the mdp.Korine’s movie is personal on a variety of different levels: inspired by his schizophrenic uncle, shot in his grandma’s house, who’s also present as a character. It’s so personal that it denies the presence of a public, and I don’t mean this in a bad way. This movie could be equally excellent if projected in a empty room, with no one watching it. This was not meant to entertain you.

I would walk my dog at night back behind the alleyways in the neighborhood where I live in Nashville. And sometimes I would see these trash bins propped up against garages or lying on the ground. These overhead lights would be shining on them, giving them a real dramatic effect. The trash bins began to resemble human forms to me — almost like a war zone where the trash bins had been molested and beaten up and stuff. Sometimes, the way they were propped, they looked very humpable. Then I remembered that in my neighborhood growing up, there were these elderly peeping toms who would stare into my neighbor’s window. They lived in an old person’s home down the road, and they would come out at night. – Harmony Korine

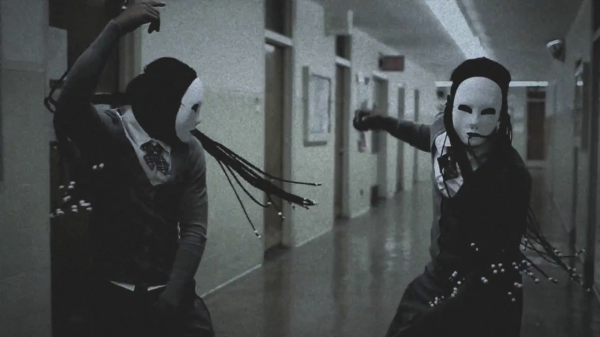

A colorful orgy of violence and laughs. The hyper-stylized scene depicting the massacre of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern from Carmelo Bene’s Un Amleto di Meno (One Hamlet Less) is an excellent example of the iconoclastic power of Bene’s cinematic style.

This is one of those films that I’ll probably never be able to explain why I like so much. Or better, I have nothing to say except “watch it yourself, then maybe we’ll talk about it”. The acting (most of the actors were non professional, and never did anything after this), the cinematography, the pace, the dialogues, the camera movements, they all combine into something rare. Unfortunately, these stills don’t really function. Even when the camera doesn’t move all that much there’s still something that makes the scene alive, something that I couldn’t capture with this images.

I remember the way Haneke’s movies always startled me. It was the glacial hostility towards the viewer. There wasn’t any irony in the way Haneke mistreated cinematic language, his solutions were always questioning the limits and possibilities of cinema. The White Ribbon, as I recall, was instead more traditional (if we can ever label Haneke as traditional). Amour, somehow, continues along this path. There’s no brutal editing (71 fragments, Code Inconnu), no games between fiction and reality (Chaché), no metafilmic solutions (Funny Games, Benny’s Video). Even so, the film manages to “rape the viewer” as usual.

I remember the way Haneke’s movies always startled me. It was the glacial hostility towards the viewer. There wasn’t any irony in the way Haneke mistreated cinematic language, his solutions were always questioning the limits and possibilities of cinema. The White Ribbon, as I recall, was instead more traditional (if we can ever label Haneke as traditional). Amour, somehow, continues along this path. There’s no brutal editing (71 fragments, Code Inconnu), no games between fiction and reality (Chaché), no metafilmic solutions (Funny Games, Benny’s Video). Even so, the film manages to “rape the viewer” as usual.Amour takes place in a single location, the house of the protagonists, except for the prologue (a perfect couple of minutes that, if seen at the cinema, could be really disquieting, even if I can’t exactly explain why). We’ll get to know this house soon and we’ll hate this sort of purgatory, where Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) wanders slowly, while his wife Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) is paralyzed in bed, slipping into dementia, just waiting to die. Despite the subject, Haneke succeeds in portraying the humiliation of old age and the physical deterioration of sickness in an explicit, yet almost whispered way. He doesn’t aim to embellish the most degrading situations, but neither does he exploit them. Apart from a few scenes which I found totally useless, if not embarrassing (yeah, there’s a nightmare scene that could have been avoided), Haneke’s long takes are surgically precise as always. If you still have impressed in your memory *that* scene from Caché, expect a similar one, masterfully placed, that’ll stay with you for a long time.

Needless to say, Trintignant and Riva are just perfect and stay high above all the other (actually very few) actors, even Isabelle Huppert. Emmanuelle Riva is bound to act with just one side of her body, but she manages to portray the proudness and strenght of her character with just a flicker of her eyelid or the position, firm yet trembling, of her hand. Trintignant does a tremendous job, portraying a tired old man, dealing with a weight too heavy for his shoulders. The best, and more caustic, lines are reserved to him, but despite the cruelness those word are spoken in such an innocent and disenchanted way that they almost bites your throath.

Without sacrificing his style in favor of over simplistic solutions, Haneke, maybe for once, seems more human towards his characters. Even if there’s no cinematic subversion as before, there’s still the brutality of reality. It’s in the words, in the screams, in the blabbering, and obviosly, in all the silences: the sad ones, the angry ones, the horrified ones, the resigned ones. And then, there’s just silence.

So, I don’t really know what happened. I mean, I fell in love with Ayoade since I first saw The IT Crowd, and then he kept popping up here and there on other british TV series (yeah, they only use like ten actors but they know what they’re doing) and my love for him only increased. So, when I discovered he directed a movie I was more than interested, but from the few stills I saw it seemed like something that I would surely hated. I can’t stand Wes Anderson and almost the 90% of indie Sundance comedies and stuff like that, and Submarine seemed like a proud parade of hipster paraphernalia. And, in fact, it kind of is. But, and I’m surprised myself, I liked it. A lot. And I’m still trying to understand why.

First of all, for a directorial debut, Ayoade is surprisingly good: there’s rhythm, there’s composition, a good balance between hand-held camera (apparently you don’t get fundings if you don’t make a shaky camera movie) and contemplative shots, supported by a functional cinematography.

First of all, for a directorial debut, Ayoade is surprisingly good: there’s rhythm, there’s composition, a good balance between hand-held camera (apparently you don’t get fundings if you don’t make a shaky camera movie) and contemplative shots, supported by a functional cinematography.So, super8 bits, coats, heart-shaped sunglasses, assorted vintage clothing, assorted vintage furniture, polaroids, witty/nerdy dialogues, sociopathic characters and so on. Yet, in its entirety, it’s not the usual pseudo post-modern i’m so ironic hipster wannabe anderson like movie. It seemed to me that there is something more, something subtle that doesn’t piss me off like these films usually do. The british vein is recognizable in the dialogues and situation, and that can only be good, but it’s not just that.

The first part is the most “already seen” part, mostly because it’s the part where the movie tries in every way to appear cool and hip and blah blah, mostly with the stuff that I’ve mentioned before, even though the result is not that bad. Anyway, in the second part all of this seems to vanish, the characters actually acquire some deepness and the story evolves in a more mature tone, but maintaining an effective humorous verve.

The first part is the most “already seen” part, mostly because it’s the part where the movie tries in every way to appear cool and hip and blah blah, mostly with the stuff that I’ve mentioned before, even though the result is not that bad. Anyway, in the second part all of this seems to vanish, the characters actually acquire some deepness and the story evolves in a more mature tone, but maintaining an effective humorous verve.The acting is impressive, the protagonist is portrayed by an excellent Craig Roberts, who’s character seems to come straight out of Harold and Maude. But between the two main characters, Yasmin Paige is the real deal, she’s wonderful and adorable and the best performance in the movie. Then we have a hilarious and often tragic Paddy Considine, who also debuted last year as a director with Tyrannosaur, one of the best movies of this last decade, along with Sally Hawkins and a superb Noah Taylor.

So, a really nice surprise indeed. Ayoade is great as a comedy actor, but I hope he will continue making movies, maybe on a different genre or subject to test his directorial abilities, because as for now, he has shown great potential.

I started with the intention of writing a review of Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus, but I can’t really come up with something.

There’s muddy waters and savage grass, empty lights and neon signs, bullet holes and churches, sweat and tears, crooked teeth and missing fingers, wrinkles, junkyards, heart broken music. In the deepest south, what Flannery O’Connor called wise blood.

It’s not a documentary, it’s not a movie, doesn’t matter, it’s raw and bleedin’.

Read more…

Read more…

There’s muddy waters and savage grass, empty lights and neon signs, bullet holes and churches, sweat and tears, crooked teeth and missing fingers, wrinkles, junkyards, heart broken music. In the deepest south, what Flannery O’Connor called wise blood.

It’s not a documentary, it’s not a movie, doesn’t matter, it’s raw and bleedin’.

Diego’s life’s built on repetition: his job is counting people as they enter a large government building, he watches soap opera with his wife, and with the same distant interest he has sex with her. The return of his daughter, from a previous marriage, will crack his routine, to the point of no return.

Diego’s look is always distant, his movements are slow and fatigued as if his shoulders were to support some sort of sisyphic weight. Each action in his everyday life is portrayed with sloppy disgust. Everything is slow, mechanical, almost empty. Even sex is a routine that has to happen, no matter how detached it can be.

Diego’s look is always distant, his movements are slow and fatigued as if his shoulders were to support some sort of sisyphic weight. Each action in his everyday life is portrayed with sloppy disgust. Everything is slow, mechanical, almost empty. Even sex is a routine that has to happen, no matter how detached it can be.

Sangre is a merciless slow parade, that combines the coldness of Haneke’s compositions with the sweat of Reygadas’ bodies. The camera barely moves during the entire film, giving the shots a static tone that emphasizes the slow descent of Diego. Escalante’s eye has a surgical cruelty that allows him to move from black humor to nihilism in a few seconds. The final scene, as well as the opening, is static tragedy at its best.

There are no characters, just bodies, sweat and flesh. Even if they move, the camera remains still, so that the frame cuts these bodies, leaving parts out of the picture. A perfect example of the cruel indifference of Escalante’s eye, that deliberately ignores what happens in front of him.

There are no characters, just bodies, sweat and flesh. Even if they move, the camera remains still, so that the frame cuts these bodies, leaving parts out of the picture. A perfect example of the cruel indifference of Escalante’s eye, that deliberately ignores what happens in front of him.

The absence of music contributes to the general feeling of emptiness that wraps the viewer, a mix between sadness and anguish. Far from being perfect, Sangre is raw and young, yet it also reaches a defined style, not easy to approach but powerful nonetheless.

(Carlos Reygadas, apart from being a major influence on Escalante’s style, is also one of the associates producers of this movie.)

Diego’s look is always distant, his movements are slow and fatigued as if his shoulders were to support some sort of sisyphic weight. Each action in his everyday life is portrayed with sloppy disgust. Everything is slow, mechanical, almost empty. Even sex is a routine that has to happen, no matter how detached it can be.

Diego’s look is always distant, his movements are slow and fatigued as if his shoulders were to support some sort of sisyphic weight. Each action in his everyday life is portrayed with sloppy disgust. Everything is slow, mechanical, almost empty. Even sex is a routine that has to happen, no matter how detached it can be.Sangre is a merciless slow parade, that combines the coldness of Haneke’s compositions with the sweat of Reygadas’ bodies. The camera barely moves during the entire film, giving the shots a static tone that emphasizes the slow descent of Diego. Escalante’s eye has a surgical cruelty that allows him to move from black humor to nihilism in a few seconds. The final scene, as well as the opening, is static tragedy at its best.

There are no characters, just bodies, sweat and flesh. Even if they move, the camera remains still, so that the frame cuts these bodies, leaving parts out of the picture. A perfect example of the cruel indifference of Escalante’s eye, that deliberately ignores what happens in front of him.

There are no characters, just bodies, sweat and flesh. Even if they move, the camera remains still, so that the frame cuts these bodies, leaving parts out of the picture. A perfect example of the cruel indifference of Escalante’s eye, that deliberately ignores what happens in front of him.The absence of music contributes to the general feeling of emptiness that wraps the viewer, a mix between sadness and anguish. Far from being perfect, Sangre is raw and young, yet it also reaches a defined style, not easy to approach but powerful nonetheless.

(Carlos Reygadas, apart from being a major influence on Escalante’s style, is also one of the associates producers of this movie.)