Čudni kućni drone-country.

andrewweathers.bandcamp.com/album/what-happens-when-we-stop

www.andrewweathers.com/

Another incredible album from my favoritest fucking guy. What Happens When We Stopis a cross country album, started in North Carolina with Weathers’ buds, elaborated on the road headed out west, and finished up with his pals in California. This one’s just as wonderful as the last, Guilford County Songs, but still not quite as masterful as the debut,We’re Not Cautious. There’s a notable lack of prominent banjo, and I fucking love the banjo, but a big focus on the guitar, more so than before, which is awesome because the guitar work just gets better with each release. Everything is just as warm and incomparably serene as ever, old American folk perfectly melded with contemporary drone & neo-classical, subtle electronics peaking through the twinkling piano, harmoniums humming beneath hypnotic acoustic strumming, but Weathers’ voice has changed a bit, a lower tone and letting his drawl shine through, a little disorienting at first, but it still works beautifully, and honestly, the guitar, just so fucking sweet with those drones, I could listen to Weathers pick away all day with the strings & brass & reeds & everything else droning in the backseat, it’s the most heavenly sound you can get. This dude is unstoppably awesome and I will devour everything he throws at us. You should probably join me in my devouring and pick this up, it comes with a sexy photo book with the work of AARON CANIPE, so you’re definitely getting your money’s worth. - antigravitybunny.com/?p=7898

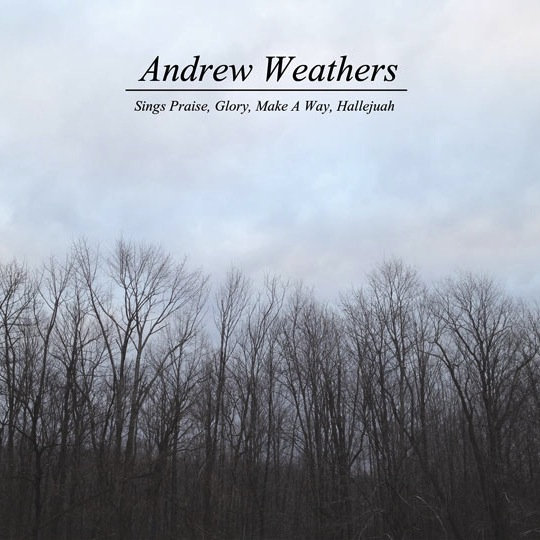

Sings Praise, Glory, Make A Way, Hallelujah (2013)

andrewweathers.bandcamp.com/album/sings-praise-glory-make-a-way-hallelujah

Andrew Weathers

“Taking Names Blues”

The electric guitar is no stranger to the worlds of ambient and drone. Often we hear guitars drenched in layers of reverb and echo, serving as a melodic fixture within a bold ambient landscape. The guitar also frequently functions as the motor behind drone music and is probably too often mistaken as being analog synthesizers. Andrew Weathers makes music that certainly has ambient tendencies, but it stars the acoustic guitar in a drone-like setting. While modern drone music can often be witnessed mingling with shades of folk and Americana styles, Weathers makes modern Americana music while mingling with drone characters.

The sepia-toned-out video for “Taking Names Blues” does a very fine job of depicting the auditory happenings within the lead-off track of Andrew Weathers’ split cassette with Ancient Ocean — out on Rubber City Noise. The video features four separate quadrants of film. The first and fourth quadrants show visions of driving past leafless trees, icy bodies of water, and telephone wires; while the second and third quadrants feature spinning footage of these winter trees. The changing landscape follows Weathers’ aimless yet steady finger-plucking journey on his acoustic guitar through classic American raga themes, while the constant yet dizzying images imitate the rotating undertone of drone that sticks with the recording throughout. Ancient Ocean’s side of the tape also features mesmerizing guitar motifs, but they play a bit more of a supporting role.- www.tinymixtapes.com/

LAYERS: Unpacking The Andrew Weathers Ensemble's "Hard, Ain't It Hard"

This week, we take a step way outside the usual LAYERS fare and delve into the folky vibes of Oakland’s Andrew Weathers and his ensemble. “Hard, Ain’t It Hard” by Oakland, California’s The Andrew Weathers Ensemble. Originally from North Carolina, the composer and instrumentalist recently released What Happens When We Stop on Full Spectrum Records. The album paints a rural picture of touring across the US with the lyrics comprised of reworked folk classics and instrumentals drawing inspiration from everything from sound collage to The Dream.

“Hard, Ain’t It Hard” is Weathers rendition of the Woody Guthrie classic, soaked in travel-weary wear and tear. Here, the booming vocals serve as the backbone while the ensemble’s improvisations subtly surround and build the track into something beautiful. Weathers and his crew combined a surprising amount of digital manipulation to achieve the unique sound, read below to hear him break it down:

What Happens When We Stop is made up of loosely-composed guitar pieces that I had the band improvise with. It’s a record about the players just as much as the technology. All of the lyrics, with the exception of one tune, come from American folk and blues songs – the text structures and shapes the improvisation.

The Ensemble is spread all over the country but I wanted to try my best to have everyone on this record. We did the first sessions at Michael O’Shea’s studio in Asheville, NC in order to get the east coast players in, now that I’m living in the Bay Area. We tracked everything live and built a majority of the album from those sessions. The rest was recorded around Oakland, at my small home studio and Mills College’s CCM, friends houses and coffee shops. I produce everything myself using Reaper, but most of my sound design is in AudioMulch, MaxMSP, and Reaktor. I make a point to not get locked into specific programs to avoid the tropes that software forces one into. Locking yourself into one piece of equipment is like locking yourself into a particular key – you can do a lot but the work turns homogenous once you look at it from a wider vantage point.

Guitar And Voice:

“Hard, Ain’t It Hard” is a reworking of a Woody Guthrie tune of the same name. The harmony of the song is more structured than my usual source material, so I left my guitar part open to improvisation more than I’m used to. I recorded the guitar and original vocal in the CCM’s studio late one night. I still play the first guitar I ever bought when I was about 15 or 16; it rattles and sometimes it’s a battle to keep it in tune. I recorded the tune with an extra verse at the end, but I felt like it was a little long-winded that way. I had one mic on the vocal, one at the 12th fret, one pointed at the body of the guitar just below the sound hole and one pointed at me from about six feet away. All four mics are faded in and out in the mix.

Processed Harmony Vocals:

I wanted the background vocal harmonies to sit somewhere between early country and The-Dream’s upbeat moments. There is autotune and pitch shifting on all of the vocals, and a little bit of reverb on the main vocal. I tend to use huge room sounds in very small amounts. I’m just using Reaper’s built in plug-ins for all of this. My friend Mel also sings in the chorus – I stopped by her apartment one day and she nailed several songs she had never heard before. I think you can hear her husband Aaron, who plays accordion on this track, making coffee at some point.

Second Guitar, Tenor Sax, Harp:

Next I added a second guitar, tenor sax and harp. Jacob added guitar that fits within the nooks and crannies of my playing. He is much better at guitar than me. All of the breathy sounds are Josh playing tenor sax – what I really loved about his take is that he blends with the later electronics in such a way that they become almost indistinguishable. Most of the edits are fairly simple, just done with volume automation and occasional cut and paste for riffs that I particularly liked.

Electronics, Accordion, ‘Famous Wedding’ Sample:

Erik Schoster plays most of the electronics that you hear on this record – he’s developed his own software called Pippispecifically for laptop improvisation. He played with us for a good portion of our tour this summer and fit in perfectly. He sent me audio of him improvising without hearing the tunes and I edited his work into the pieces. At the very end of the track you can hear a sample derived from an a capella version of a folk tune called ‘The Famous Wedding’, I made it mostly with granulation and filters in AudioMulch. The granulator there is pretty incredible, probably my favorite feature in the program. Also here are Aaron Oppenheim on accordion, Evelyn Davis on piano and Scott Siler on vibraphone. Their parts filled out the texture, basically covering the role that electronics take in my past work. That’s really the thing I love about moving between electronic and acoustic worlds.

Put them all together and here’s what you get. The premiere of “Hard, Ain’t It Hard” by The Andrew Weathers Ensemble:

thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/layers-unpacking-the-andrew-weathers-ensembles-hard-aint-it-hard

Andrew Weathers is one of those polymath type of musicians that make lesser players want to toss down their instruments in frustration. The North Carolina-born, California-based artist has earned it though. He’s been studying both acoustic and electronic composition, as well as a wide variety of playing styles with an impressive roster of teachers encouraging and training him: Roscoe Mitchell, Fred Frith, Alejandro Rutty, and Eugene Chadbourne.

Andrew Weathers is one of those polymath type of musicians that make lesser players want to toss down their instruments in frustration. The North Carolina-born, California-based artist has earned it though. He’s been studying both acoustic and electronic composition, as well as a wide variety of playing styles with an impressive roster of teachers encouraging and training him: Roscoe Mitchell, Fred Frith, Alejandro Rutty, and Eugene Chadbourne.

Interview: Andrew Weathers

Andrew Weathers is one of those polymath type of musicians that make lesser players want to toss down their instruments in frustration. The North Carolina-born, California-based artist has earned it though. He’s been studying both acoustic and electronic composition, as well as a wide variety of playing styles with an impressive roster of teachers encouraging and training him: Roscoe Mitchell, Fred Frith, Alejandro Rutty, and Eugene Chadbourne.

Andrew Weathers is one of those polymath type of musicians that make lesser players want to toss down their instruments in frustration. The North Carolina-born, California-based artist has earned it though. He’s been studying both acoustic and electronic composition, as well as a wide variety of playing styles with an impressive roster of teachers encouraging and training him: Roscoe Mitchell, Fred Frith, Alejandro Rutty, and Eugene Chadbourne.

All of this has culminated in a series of releases that find Weathers working either side of his musical brain, and on one of his most recent recordings What Happens When We Stop (released on his own Full Spectrum label), combining the two. On it, he takes long improvisations recorded with ensembles on both sides of the country, and edits them into more concise and heady pieces. The acoustic side take precedence, but the use of electronics by Weathers and Erik Schoster helps add some delightful texture to the mix.

Tonight at 8pm, this site and the folks behind Lifelike Family are happy to present a solo performance by Weathers at the Alberta Abbey (126 NE Alberta). He’ll be joined by one of his Full Spectrum artists Radere, as well as a trio of incredible locals: Ethernet, The OO-Ray, and Ruhe. But before you head out, please check out some sounds from Weathers and this interview he was kind enough to take part in.

Reading the description on the Full Spectrum site…it sounds like the process to create the music for What Happens When We Stop was a pretty involved one. How much editing/synthesizing time did it take you to create the finished product?

It was definitely pretty involved – about a year and a half from start to finish. I started writing the songs in Fall 2011, but didn’t go into the studio until March 2012. The east coast band recorded the tracks that make up the basis of most of the record at Solotechne Studios in Asheville, NC, those tracks sat until about August when I started to edit in performances from the west coast band.

Was it a hard thing to be an editor for a project like this, to make cuts where they needed to be made, etc.? Or are you confident enough in what you’re trying to accomplish that you can get through the process comfortably?

The editing process happened pretty organically. There was definitely an excess of material for this album. The players honestly made my job very easy, they are all just so good. The hardest thing that I had to do with this material was cut songs and sequence the record – I became very attached to the tunes. I think all of the tracks that we recorded will end up released somehow, though.

What about vocally on this album? How did you come up with the lyrical content? What was inspiring you at the time?

All of the lyrics (except for O/OU) I’ve lifted from folk and blues tunes. “Pale Face to the Sun” comes from Dock Boggs’ Country Blues, “Hard Ain’t It Hard” is a Woody Guthrie tune. Even though the songs are fairly old, I think they still speak to my situation, sometimes even in a surprisingly specific way. I sometimes feel like I’m wandering around the world without a culture of my own. Using folk sources is a way to feel like I’m part of something much larger than me.

Do you stick to this material live now or are you moving on to completely new sounds? If it is the former, how do you go about re-creating or re-working the material for performance? If the latter, what are you working on these days and in what medium?

These days, I’m still playing some of the same songs, some new ones in a similar vein. I like this material a lot because it’s very flexible-I can play it solo acoustic, solo with my Max/MSP patch, or with other players improvising with me. The tunes keep changing. The recordings aren’t necessarily definitive editions of these songs for me, it’s more like a fantastic realization of what the songs might be like if everybody in the band played at once. I think Eric [Perreault] and Rachel [Devorah Trapp] might be the only people other than me who have met everyone else who plays in the Ensemble. I’m also working on some performance pieces for sine waves and just intonation guitar, but I’m generally performing these tunes with my Max patch.

You’ve studied with a pretty jaw-dropping bunch of artists…what was the most important lessons or techniques or qualities that you took from those experiences?

I’m constantly blown away by the people I’ve been lucky enough to work with. I keep discovering things that I’ve learned from other artists over the years. These folks are all very very different, but they all have in common a work ethic that has influenced me a great deal. Everything good takes a lot of hard work, and I hope that I’m putting that in. Fred Frith once told me to never keep anything static in a mix.

Being a musician in this day and age is tougher than ever, as far as trying to make it your only profession. What difficulties have you run into trying to maintain your creative output?

I’ve been lucky in the past few years to have been studying music, so my day-to-day has been fairly in tune with my creative output. I recently finished my MFA though, so now I’m trying to make the full time musician hustle happen. The difficulty there is that it never ends. You don’t get any days off doing this. There’s not a single day that I don’t have something I should be sitting down and working on, especially because I handle all of the “business” end of my operation. But I love it, I wouldn’t have it any other way, even if no one seems to want to pay musicians very much money for anything.

It also says in the notes for the new album that you are a voracious listener of hip-hop music. When did that first enter your life and what in it sparked such an interest from you?

I honestly came to hip-hop very late, I’m a total dilettante on that front. In my teenage years, I was more into punk and totally overlooked hip-hop. Lil B was the first MC that really engaged me, but since then hip-hop has made up most of my day-to-day listening. I had started to feel like a lot of experimental music was stale. Four years of college in music school will do that to you. Hip-hop is just music bursting with personality, the MCs are just so huge. The production was also super appealing since I hadn’t encountered anything quite like that before, particularly as far as vocal production goes. I think the way I’ve approached using my voice in the past few years owes a lot to hip-hop.

This is the right blog for anybody who desires to find out about this topic. You realize a lot it’s virtually exhausting to argue with you (not that I truly would want…Ha-ha). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a topic that’s been written about for years. Great stuff, just nice!

OdgovoriIzbrišiwhat is mediation omaha