Grafičar i slikar koji se razvio u legendu strukturalnog filma.

Sve vidljivo je "materija" i "materijal". A materijalizam je vrsta halucinogenetike.

paulsharits.com/

PAUL SHARITS: RAZOR BLADES + KRATKA BAZA vimeo

1960-1970

1981-1993

FILM CLIPS (See Filmography)Interviews ect...

Exploded View |

Paul Sharits by Chuck Stephens

“One of his best-known works, N:O:T:H:I:N:G, features a light bulb and a chair.”

Paul Sharits remains the most structurally precise and disturbingly unknowable experimental filmmaker of the late 20th century, much written about and yet still wholly enigmatic, his work spare, blunt, baffling, often enraged, and always overwhelmingly beautiful. P. Adams Sitney long ago claimed Sharits’ N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968) as one of only three “flicker films” of its era to matter. (Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer [1960] and Tony Conrad’s The Flicker [1965] were the other two.) Indeed, Sharits has always had his explicators and advocates, then and now. There are several in- and out-of-print books and pamphlets devoted to his numerous films, “inert film” paintings, unclassifiable sculptures, tightly graphed squiggles, and infinite-loop “locational installations,” Yann Beauvais’ lushly illustrated Paul Sharits (Les Presses du Reél) chief among them. A huge archive of Sharits material is available at www.mikehoolboom.com, and Re:voir has produced a DVD of three of his quintessential “mandala” films: Piece Mandala/End War (1966), N:O:T:H:I:N:G, and T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G (1968). Yet there always seems to remain something more to be said about Sharits (born in Denver, CO, 1943), and not just when one comes across a howler like the “description” of N:O:T:H:I:N:G quoted above, found in The Buffalo News’ lengthy obit for the filmmaker, who took his own life in 1993, on his 50th birthday.

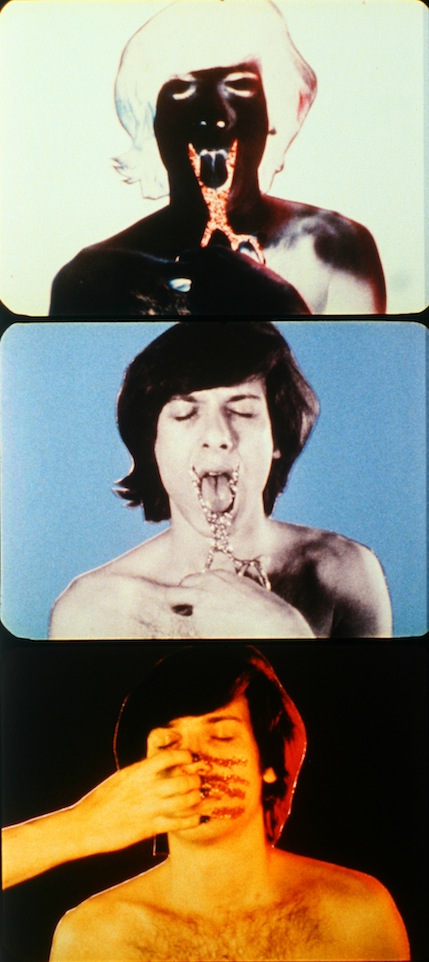

Yes, both a chair (repeated still images of a wooden one, in the process of toppling over) and a light bulb (in a series of cartoon illustrations, emanating little lines of “light” and eventually emptying out its contents) are featured in N:O:T:H:I:N:G. Combined, they comprise less than two of the film’s 36 minutes, the rest of which consists of static frames of solid colours edited in algorithmic patterns to produce sublime cascades and dazzling conniptions of flickering, drifting, flaring, and dimming hues: Rothko ochres and Woodstock grass-stain greens give birth to phantom shapes and shadow motions; the wall dissolves in waves of toy-boat blues and race-riot reds. (“I like the colours,” someone says, admiring a ’60s concert poster in Soderbergh’s The Limey [1999]. Peter Fonda concurs: “We all did.”) In T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, positive and negative still images of poet David Franks posed against a variety of solid-colour backdrops—sometimes cutting off his own tongue with glitter-covered scissors, sometimes suffering a series of glitter-stained fingernail scratches across the face—attain a fugue state of rapid alternations while the soundtrack loops and stammers the word “destroy” again and again, finally destroying the intelligibility of the word in the process.

There is often violence done to sound and image in Sharits’ cinema (and a strain of largely self-destructive violence that ran through his life), though his professed goal was enlightenment, not annihilation. Still, it may be the most crassly material concerns of Sharits’ cinema that remain the most haunting, and the most difficult to fully engage. Amos Vogel’s Film as a Subversive Art presciently noted that Sharits’ structuralist fields of colour and patterns of meditative pulsation were always balanced by and directly related to the provocations of “neo-Dada and Pop.” Hence the staggering, double-screen meta-project Razor Blades (1965-1968) and its shattered taxonomy of sprinkled stars, stuttering stripes, naked college students, Fluxus instructions on how to wipe your ass, and the preparation of a raw, red steak, cleft by a straight razor and covered with shaving cream. Sharits explained that it was all part of a vision of “the Life Cycle” in which “mundane activity [is] slashed open, revealing the positive-negative dynamics of sexuality, birth, growth, clashes at levels of reality, horror, confusion, absurdity, suicide; then, the ‘other side’ of death-filled visions of life—the razor used to slash a wrist becomes Medicine (the life-giving scalpel)…ends becoming beginnings.”

Destroydestroydestroy. Create. cinema-scope.com/

Paul Sharits

Greene Naftali Gallery, New York, USA

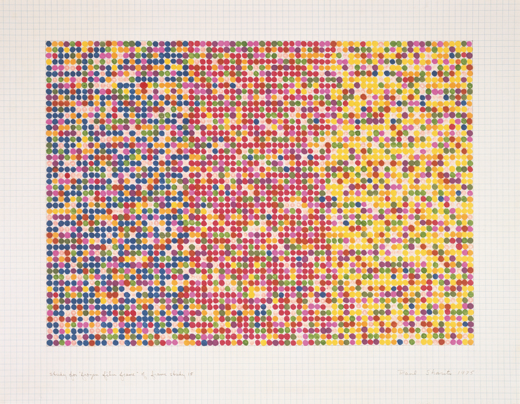

Paul Sharits, Study 4: Shutter Interface (optimal arrangement) (1975)

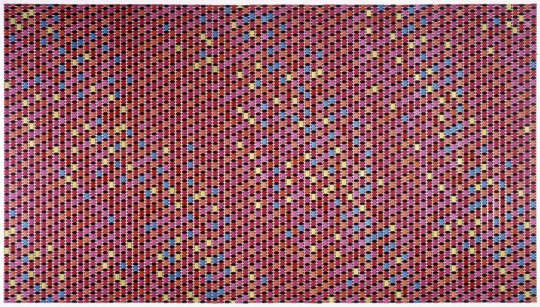

If any film installation can be compared to an endlessly prolonged execution of cinematic illusion by firing squad, it’s Paul Sharits’ Shutter Interface (1975). In this hypnotic work – recently restored by Greene Naftali and Anthology Film Archives to its long-unseen, four-screen version – a quartet of 16mm projectors stand, figure-like, side by side on imposing pedestals facing a long wall. Four looped films of varying lengths are unspooled and respooled in jewel-like swathes of colour interspersed with single black frames, creating the flicker effect Sharits – who died in 1993 – was the first to explore in colour films. The images thrown onto the wall overlap at their edges, producing ghostly paler bands where hues mix within the wide polychrome rectangle, complicating patterns that emerge like waves, horizontal pulses or, more eerily, cards shuffled by invisible hands. When the black interstices disrupt the chromatic flood, the soundtracks emit high-frequency, cicada-like tones via speakers placed underneath the projected images, aurally mirroring the whirling shutters. To best view an installation of Shutter Interface, you have to duck before the line of whirring machines and sit on the floor in front of them. Even when stationed between the projectors and the corresponding images, however, you get the sense of being a witness to a wrenching event, both a viscerally engaged and a detached observer. As Rosalind Krauss noted of another four-projector Sharits installation, Soundstrip/Filmstrip (1972), the panoramic field formed by the overlapping images echoes the Cinemascope format, but the glorious illusion typically associated with widescreen movies is continuously disrupted by the insistently sculptural projectors and bases. Instead of being enveloped, we are, as Krauss wrote, ‘at a tangent to the illusion, forcibly aware of the generative pair: projector/projected; aware, that is, of the mechanisms that are closer to the birth of the illusion.’ Sharits viewed such works as ‘locational’ installations, which he intended to be shown outside of the context of the cinema and saw as having ethical dimensions.

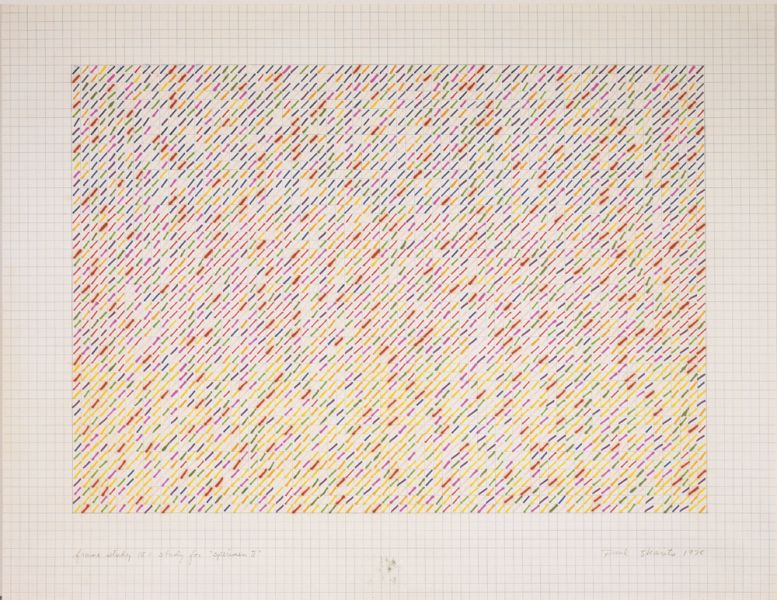

Also on view in the show were an array of drawings and studies, many of them intricate ‘scores’ for films Sharits made with coloured pencil or marker on graph paper – a method of composition that came naturally as he had studied music as a child, and one that reflected his preoccupation with bridging the boundaries between visual and aural modes of perception. Another group of sketches from the late 1970s depict detailed plans for an inverted ‘light-pyramid’ to be projected with a mirror-and-lens system onto Mayan and Aztec monuments, alongside vivid musings in which he imagines an ecstatic immolation in the ‘pursuit of light/art’.

In an article published in Film Culture during the same period, Sharits noted that he had moved away from ontological concerns toward a greater interest in ‘behavioral psychology and medical pathology’. This shift is evident in numerous marker drawings from the 1980s in which horizontal rows (loose or tightly filling the page) of garish, furiously jagged, electrocardiogram-like lines suggest an impending tsunami – a metronymic rhythm threatening to tip into engulfing chaos. In one variation, Spasmatic Pain I (Boulder Community Hospital) (1981), the frenzied lines break formation to become a whirlpool near the centre right of the drawing and are partially crossed out further down. These and other works evoke Sharits’s personal turmoil, including his bipolar disorder, but emphasizing such connections can detract from appreciating his many metaphorically rich explorations into the relationship between consciousness and perception.

Sharits’ ties to Fluxus were evident in the subversive humour animating a smattering of erotically charged ‘Flux-fashion drawings’ (c. 1990–3), energetic sketches of fanciful costumes, mainly for women, such as one depicting a ‘slut’ in a micro-mini and pubic hair bra; other designs incorporate ants, rotten fish or razor blades. These shade into puerile fantasy but are also compelling reminders of the intersection between carnality and aggression in even Sharits’ earlier, more controlled and transformative work. As P. Adams Sitney wrote in Visionary Film (1974) of a trio of Sharits’ inventive flicker films, ‘The metaphors of T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G [1969] totalize the suicidal and sexual inserts of Ray Gun Virus [1966] and Piece Mandala/End War [1966] and represent the viewing experience as erotic violence.’

That aggression and erotic pulse also lend an elemental power to works like Shutter Interface, which he structured according to ‘a dynamic of oscillations and cycles’ similar to that found in nature. These days it’s not so strange to find a 16mm projector parked in a gallery, but Sharits’ work gains a particular dynamism in this ‘locational’ context, at a time when his idio-syncratic achievements are ripe for rediscovery. He went far beyond an analysis of the materials of cinema: in his multi-projector installations, the extermination of illusion also represents an anxious, equally extended rebirth.

Kristin M. Jones www.frieze.com/

Paul Jeffrey Sharits was born in Denver, Colorado on February 7, 1943. His parents were Paul Edward Sharits and Florence May Romeo-Sharits. He had only one sibling; Gregg Leigh Sharits born on April 24, 1945.

He grew up in a nice south Denver neighborhood next door to his grandma and grandpa Romeo. While he was going to South High School he won first place with his oil painting, "WarHorses" (seen on the Sharits Gallery page).

As a young teenager, he frequented a dance hall in southwest Denver off of Lincoln Blvd. It is there that he met my mother and her sisters.

He graduated from High School in 1960 at the age of 17. He also married my mother, Frances Trujillo, that July. Florence May was...well, not happy. Paul was too young to marry, so he got a note from Paul Edward. Thus, began a very tense relationship between mother-in-law and daughter- in- law.

Paul went to The University of Denver's School of Art where he earned a BFA in Painting. He was primarily a painter, but he discovered 16mm films and his mentor Stan Brakhage. He made his first popular Wintercourse in 1962.

In 1964, he went to Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana for his MFA in visual design. On March 19,1965 my mother gave birth to me, Christopher Sharits. On August 3, 1965, my grandmother, Florence, committed suicide. Some thing the boys never recovered from.

After he received his MFA, we moved to Baltimore, Maryland. He went to work teaching at The Maryland Art Institute.

He had a "shock value" sense of humor. At one point he orchestrated a magnificent art show featuring his students. He also called the police to report a rape in a bar by Paul Sharits. When they arrived, everyone in the bar said they were Paul Sharits.

Three years later, we moved to Antioch, Ohio where he was instrumental in establishing that college's Media Studies department. From there my parents divorced and I moved with my mother back to Denver.

Dr. Gerry O'Grady, at The University of Buffalo Center for Media Studies, recruited experimental filmmakers from around the country including my father. There was my father, James Blue, Hollis Framton, Tony Bannon, and Tony Conrad. In addition there was Woody and Stenia Vasulka and Peter Weibel.

Throughout the 70's Paul continued to make films and paintings. Most reflected back to his film work. In 1979-80, Paul spent a year in Positano, Italy. I was lucky enough to spend February-April 1980 with him. During this year he produced a massive amount of acrylic line paintings aptly titled the "Posilo Series."

On September 6, 1980, his brother Gregg, also a filmmaker and illustrator, committed suicide in Berkeley, California. Paul was very close to his brother and, on top of his mother, nearly sent him over the edge.

On July 8th, 1993 his body was found peacefully in his Buffalo, New York home. I believe he actually committed suicide on the 4th, his favorite holiday.

Paul was survived by myself, Christopher Sharits, his father, Paul E. Sharits (since deceased) and the rest of my family; my wife, Cheri, our three sons, Gregory Paul, Jeffrey Patrick, and Robert Christopher.

Why so much pain and anguish in one family? Bipolar disorder. It runs in the family. There is a lot of misconceptions about bi-polar disorder. For one, many people don't realize some of our most cherished, talented, high functioning achievers were and are bi-polar. If you wish to learn the truth about the Sharits family and others struggle with bi-polar disorder, select the "About Bipolar disorder" tab.

"PAUL SHARITS was not one to silently tiptoe through life and art. He was driven, he wrote in one of his many notations, by "inescapable anxiety." He guessed that anxiety was what kept him working, kept him leaping from one creative project to another."

-Buffalo News July 18, 1993 Richard Huntington - paulsharits.com/

-Buffalo News July 18, 1993 Richard Huntington - paulsharits.com/

American avante-garde “experimental” filmmaker, artist, and professor of media studies, Paul Sharits, was born in Denver, Colorado on February 7, 1943. Tragically, he died on July 8, 1993 in his home in Buffalo, NY. He is survived by his son, Christopher, Christopher’s wife Cheri, and three grandsons.

Paul is widely known for his structural films, the use of multiple projectors, infinite film loops, experimental soundtracks, and interventions at the level of the filmstrip in order to realize his elemental mode of cinematic presentation. Paul went to The University of Denver’s School of Art (DU) where he earned a BFA in Fine Arts. At the time he was known as a young painter, however, he had been making films since high school. While studying art at DU, he began a mentorship with Stan Brakhage that soon became a lifelong friendship. Stan’s manipulation of film structure through experimental and “scratch” film’s influence is evident in Paul’s early work.

In 1964, he attended Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana for his MFA in visual design. After he received his MFA, he moved his family which consisted of his son, Christopher, and his wife, Frances, to Baltimore, Maryland where he taught at The Maryland Art Institute. Later, he taught at and became a pinnacle force behind the development of the Center for Media Studies at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. He divorced his wife in 1968. Shortly thereafter, he was recruited by Dr. Gerry O’Grady at The University of Buffalo Center for Media Studies along with the most prominent emerging experimental filmmakers of the time which included James Blue, Hollis Framton, Tony Bannon, Tony Conrad, and later, Peter Weibel.

Paul enjoyed relative acknowledgement during his lifetime, with shows at the Bykert Gallery, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and Walker Art Center among other institutions, and has been posthumously exhibited at the Whitney Museum, MoMA, Pompidou, Louvre, and the Burchfield-Penney Art Center in Buffalo, New York as well as the widely renowned Greene Naftali Gallery exhibition of both his works on paper and his four projector installation “Shutter Interface” which was nominated for “Solo Exhibition of the Year” at the 2009 First Annual Art Awards at the NYC Guggenheim Museum. The four projector “Shutter Interface” installation was acquired by and is now on exhibition in the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C..

Trained initially as a painter, and a prolific theoretical writer, Sharits’ art-making was in fact wide-ranging, evidenced by his early involvement with Fluxus artists in New York. His many works on paper—from diagrams to abstract film scores, fashion drawings, and hallucinogenic illustrations—have yet to be fully integrated into his better-known body of work. —paulsharits.com

- mubi.com/Pixel Paul

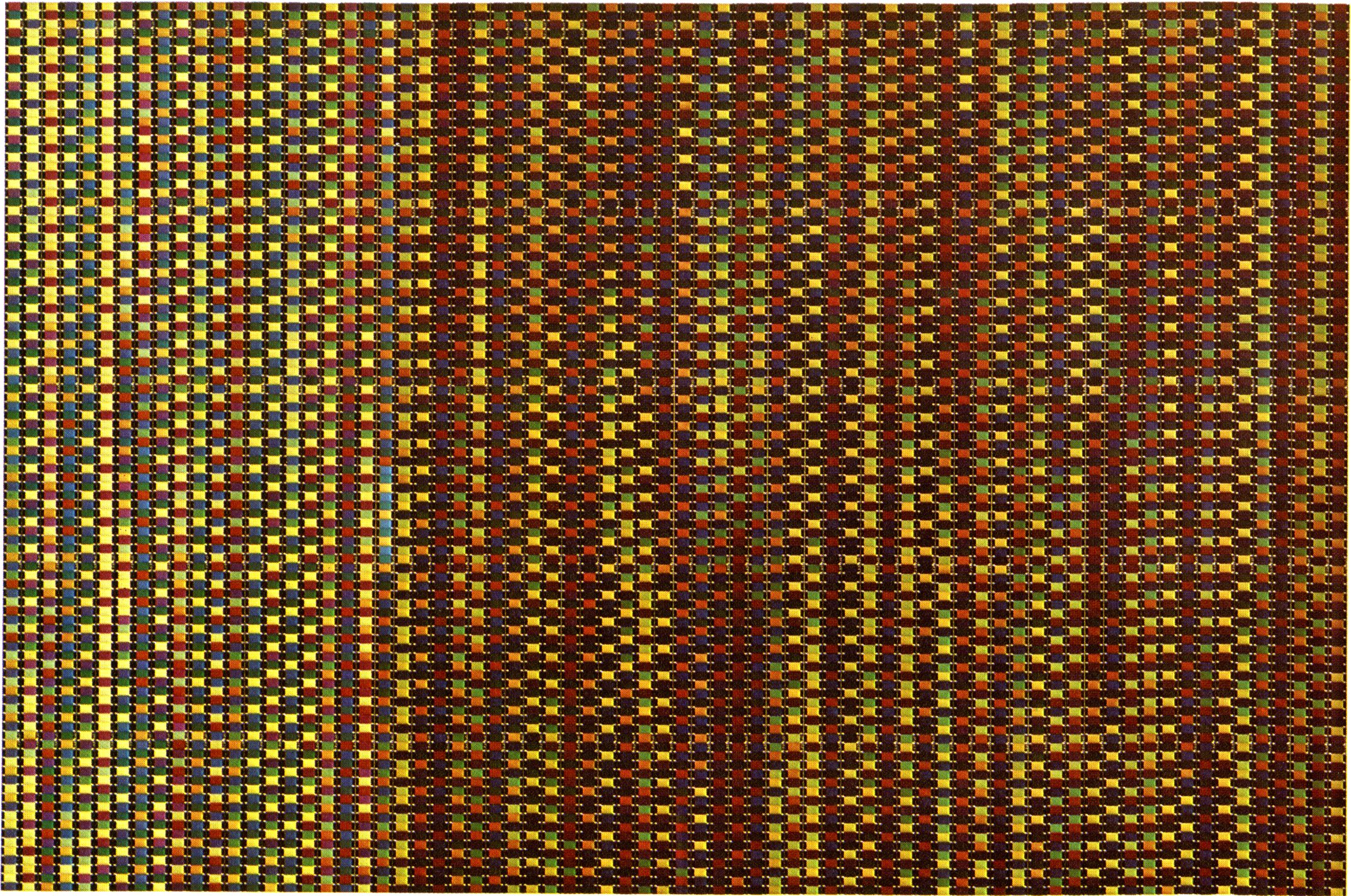

Study for Frozen Film Frame of "Frame Study 15" (1975)

Though experimental filmmaker Paul Sharits' incredibly detailed film scores depict plans for possible films, they have a manic beauty all their own. Some of his most fascinating studies, like the one above, served as plans for his Frozen Film Frame series, in which colored film strips are sandwiched between plexiglass and hung from the ceiling, allowing natural light to illuminte their multicolored frames.

From Frozen Film Frame series (1971-6)

Another example, below, was a study for his Specimen series.

Frame Study 15: Study for “Specimen II,” 1975

From Specimen

Undeniably alluring, Sharits' plans, which don't necessarily synchronize with a finished product, point towards his desire to bring cinema into a non-theatric mode of presentation. Viewed today, the images have endless, striking associations with pixels and glitches. Sharits' emphasis on the object of film in the Specimen and Frozen Film Frame series presages the materiality of blocky low-res aesthetic visibile in much contemporary electronic art.

- rhizome.org/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar