Nijedna poznata teorija o nastanku svijeta nije točna. Ovaj ludi i šaljivi svemir stvorio je golim rukama shizofreni švicarski slikar Adolf Wölfli. Za to mu je trebalo 1400 crteža, 1500 kolaža i 20 000 rukom ispisanih stranica okupljenih u ručno uvezane knjige. Bio je matematičar koji je stvorio svoju pijanu algebru (zato još i danas znanost tapka na mjestu pred tajnom nastanka Svega), glazbenik (izvodio je vlastite kompozicije puhanjem u papirnate rogove), i naravno, putnik. Naslov jednog od njegovih putopisa, preveden na engleski, glasi ovako: Scientific Voyages, Hunting Expeditions, Casualties, Adventures, and other experiences of one gone astray on the whole earth globe; Or, a servant of God, without a head, is poorer than the poorest wretch.

Idila se naglo izvrće u katastrofu, i obratno.

Imaginary Autobiography:

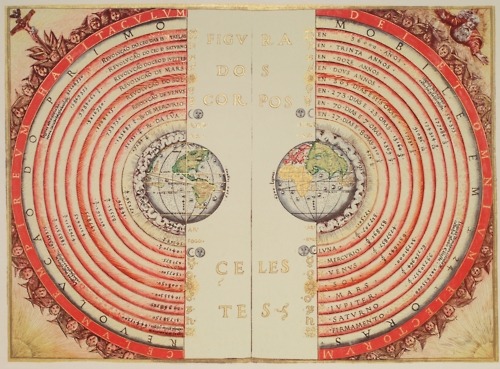

From 1908 to 1930 Wölfli recreated his life, the world and eventually the cosmos in a massive series of works totally more than 19,340 pages.

1908 - 1912: "From the Craadle to the Graave." He sees his life as in need of recreation, by fictionalizing his past ordeals.

1912 - 1916: the "Geographical Hefte." begin his architectural and town planning schemes, thence his travels to imaginary places and, finally, cosmic voyages.

1916 - 1930: Wölfli becomes "St. Adolf II" which he sees as having been earned by sixteen years of hard work. His recreations take on the character of a religious mission for himself.

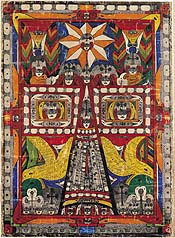

1922 - 1928: over 200 mandala drawings see Wölfli fully realising the role of archetypes, the cosmic egg of alchemy, in such a mission. Everyhing falls within its scope.

1926 - 1930: Sixteen volumes of the Funeral March consist of a series of short or phonetic phrases separated by indications of rhythm. This song is interrupted by short geographical texts, prayers, or bible quotations. It is the world and Adolf Wölfli become One, a work of great complexity which is rivalled in its encyclopedic scope only by Joyce's "Finnegan's Wake." Never before published, it is now in its final stages of preparation.

ADOLF WÖLFLI (1864-1930)

Adolf Wölfli Foundation, Museum of Fine Arts Bern, Switzerland

At

the beginning of the twentieth century, Adolf Wölfli, a former farmhand

and laborer, produced a monumental, 25,000-page illustrated narrative

in Waldau, a mental asylum near Bern, Switzerland. Through a complex web

of texts, drawings, collages and musical compositions, Wölfli

constructed a new history of his childhood and a glorious future with

its own personal mythology. The French Surrealist André Breton described

his work as "one of the three or four most important oeuveres of the

twentieth century". Since 1975, our aim is to make Adolf Wölfli's work

known through one-man and group exhibitions as well as publications.

„From the Cradle to the Grave“ (1908-1912).

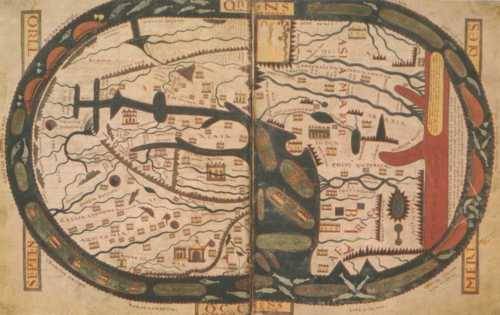

In 3,000 pages, Wölfli turns his dramatic and miserable childhood into a

magnificent travelog. He relates how as a child named Doufi, he

traveled „more or less around the entire world,“ accompanied by the

„Swiss Hunters and Nature Explorers Taveling Society.“ The narrative is

lavishly illustrated with drawings of fictitious maps, portraits,

palaces, cellars, churches, kings, queens, snakes, speaking plants, etc.

In the second part of the writings, the „Geographic and Algebraic Books“, Wölfli describes how to build the future „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“: a huge „capital fortune“ will allow to purchase, rename, urbanize, and appropriate the planet and finally the entire cosmos. In 1916 this narrative reaches a climax as Wölfli dubs himself St. Adolf II.

In the subsequent „Books with Songs and Dances“ (1917-1922) and „Album Books with Dances and Marches“ (1924-1928), Wölfli celebrates his „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“ for thousands of additional pages, in sound poetry, songs, musical scales (do, re, mi, fa...), drawings, and collages. In 1928 he starts with the „Funeral March,“ the fifth and final part of his great imaginary autobiography. In over 8,000 pages he recapitulates central motifs of his world system in the reduced form of keywords and collages, weaving them into a infinite tapestry of sounds and pictures, a fascinating requiem ending only with his death in 1930.

As a mulitple outsider, Wölfli used the world as a quarry for constructing a complex mental edifice complete unto itself. The „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“ was both a kind of wish-fulfillment machine and the result of his obstinate reception and reproduction of turn-of-the-century ideas, values and phantasies. Wölfli created a body of work that was part of its age in terms of content, yet clearly alien to that age's conventions.

Jean Dubuffet, the French artist and founder of „Art Brut,“ called Wölfli „le grand Wölfli,“ the Surrealist André Breton considered his oeuvre „one of the three of four most important works of the twentieth century,“ and the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann showed a number of his pieces in 1972 at „documenta 5,“ the renown contemporary art exhibition in Kassel, Germany. Wölfli's writings, which he considered his actual life's work, only began to be systematically examined and transcribed in 1975 when the Adolf Wölfli Foundation was founded. Elka Spoerri (1924-2002) built up the Adolf Wölfli Foundation and was its curator from 1975 to 1996.

|

Early Work: Drawings, 1904-1906

During

his first years at Waldau Wölfli was an agitated and violent patient.

In 1899, about four years after his hospitalization, his state improved

(as noted in his medical history). At this point, Wölfli had begun to

draw. Since no drawings have been preserved from 1899 to 1903, the

entries in the medical history remain the only testimony on the

beginnings of Wölfli's art: "Patient passes the time with drawings."

(November 1899) One year later we read that Wölfli "draws a lot of notes

and composes (he says) large pieces of music." In January 1902 Wölfli

is said to "be calmer, since he is allowed to draw and gets every week a

new pencil," and in October: "He has drawn very industriously for the

entire summer and used up his pencil weekly; his drawings are very

stupid stuff, a chaotic jumble of notes, words, figures, and he gives to

the individual pieces fantastic names such as: 'Trumpetstrands,' 'Lower

Abyss,' etc."

Adolf Wölfli "Petrol", 1904 |

In the drawings of 1904-1906, Wölfli uses a variety of shading devices such as cross-hatching, dots, and stripes to make the forms stand out individually and to produce contrasts of light and dark. Together with the straight and circular contour lines drawn freehand, these shading devices and fillers are testimony to his great ability as a graphic artist. He himself sometimes calls his drawings "copper engravings" and "steel engravings."

The identification of the different superimposed motifs is made difficult by the prevalence of ornamental interlace. The forms fall into the following basic divisions: transformational ornaments, ornamental strips, form as filling, signs and geometric forms. Though they are sometimes used separately, they are frequently combined and made to serve more than one function simultaneously. The following description of the ornamental forms and the schematic drawings are intended as an aid for the observer.

The most important transformational ornaments are the "snails." They are the simplest structures and consist of a longish, flat crescent shape sometimes marked with a line and a dot as an eye and ear, sometimes with just a line. In some drawings Wölfli gives them specific names: (1904) "Light-Snail," "Bandage-Snail," "Snail-Star-Ring," "Noga-Snail-Star," "Herdsman-Snail," "Herdswoman-Snail". The snails appear singly or as symmetrical pairs, sometimes in bundles and sometimes in bands. Larger snails with pronounced eyes look like mice or rats.

The "bird" form, which later becomes the single most important element of Wölfli's vocabulary, is not yet fully developed in the early drawings (the typical "bird" attains its definitive form from 1908 on, in the illustrations of the narrative work). In the early drawings the birds are still very similar to the snails; they differ from them only in their articulated curved necks and their slightly raised tails; they are still drawn without feet. To some of these snail/bird figures Wölfli gives names, such as "Christ-Bird," "Fountain-Bird," "General-Bird," "Midwife-Bird," "Music-Barrel-Bird" etc.

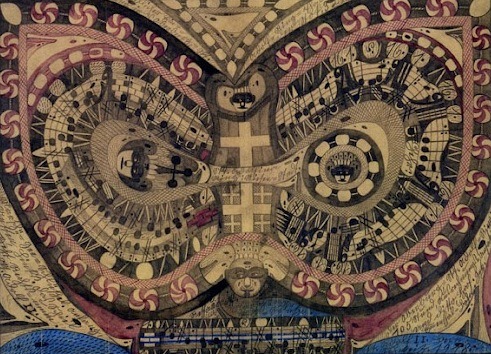

Wölfli called the ornamental bands rings. The most important one is the ring of bells, composed of circle or oval forms. Knotted into a simple band, it is comparable to a string of pearls or the classical egg motif. The bells are intricately decorated with various cross-hatchings and shadings. Centrally located screwlike lines turn them into balls of wool or rosettes. Ornamental bands can be added to the rosette, peacock-eye, zigzag, and brickwork patterns.

The signs used are primarily the letters B, E, H, I, N, Z, and of course A and W. Originally used as initials -- A. W. for Adolf Wölfli and E.B. for Elisabeth Bieri -- the letters can become linking elements of the composition of a picture. The symmetry of H, N, and Z -- top equals bottom, right equals left -- makes them especially useful as linking elements. In 1905 Wölfi inserted human faces into the empty spaces of the letter, for instance, in the arched space created by the crossbar of the letter H. The letters become compressed, thus making the shaped spaces into figurations that can be read as both positive and negative images. They are an example of the binary perception in Wölfli's work by means of which positive and negative spaces are equally readable and alternately size the viewer's attention.

The great many numerals in the drawings are usually indications of musical rhythms. Throughout his work Wölfli uses the number series 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32. The number 64, the last number of the hexameter, Wölfli does not execute, in either the early or the later drawings, but he reaches the number 64 in the mandala composition Catholic Spiritual Center Rome, drawing the number 8 eight times (8 x 8 = 64).

The "eye-mask", which, like the bird, is another typical and important motif later, is not to be found in the early drawings. Here the eyes look straight ahead and are not turned to the side as they are in the faces wearing masks in the drawings after 1914.

The scenes in the early drawings consist of naturalistically drawn figures of people, animals, interiors, and landscapes. Most renderings are portraits or self-portraits. In the 1904-1906 drawings Wölfli always represents himself as an adult and not as the child "Doufi," his alter ego, who becomes the protagonist in the narrative work.

Alongside his friends and acquaintances -- for instance, Elisabeth Bieri, Magdalena Reber, and Rosa Schenk -- Wölfli portrayed public figures of the political and cultural spheres ; the men carry weapons: rifles, swords, spears, as well as an axe, a fishing rod, a cane, a bat, a flag, or a sceptre ; the female attributes are elaborate hairdos decorated with flowers, aprons, high-heeled shoes, mirrors, trailing skirts, purses, and parasols. Landscapes and architecture are rendered naturalistically. We see, among other things, mountains, trees, farmhouses, hotels, monuments, fountains, bridges, portals, arcades, windows, screens, staircases, etc. The interiors are equipped with clocks, candle holders, and lamps. Animals represented are the fish, cat, ram, horse, cow, goat, and panther.

The early drawings elude a conclusive interpretation of the content. Of the manifold strands of superimposed themes and possible readings we can isolate only some meanings, and even those are sometimes partial. The appearance of mandalas in the early drawings has to be viewed as a breakthrough of great import: unified geometric order replaces chaos.

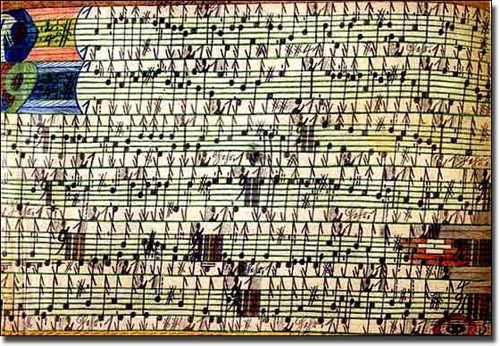

Music is another aspect of the content of the early drawings. The appearance of such a primary symbolic form as the mandala and the primary mathematical principle of binary pattern and progression, which characterize Wölfli's earliest work, are of great significance, indicating his quest for harmony. In view of this strong impulse toward harmony, it is not surprising that Wölfli preferred to think of these drawings as musical compositions. He calls them "sound pieces" and signs them "Composer." They have little in common with the usual forms of music notation: the staves are empty and any indications of rhythm (e.g., "2:1," "4:2"), duration ("music end," "music begin"), or instrumentation ("trumpet," "tam," "cymbal") are written on separate areas of the drawings. The lost pages with solmization rightly deserved the designation "sound pieces." On the other hand, perhaps the empty staves in the drawings indicate that Wölfli conceived of music not only as melody but also as the visual sight/site of sound.

Only a single drawing exists from 1906, „Giant-Bell Grampo-Lina“. That no further drawings are preserved is astonishing, for at the end of 1906 Wölfli wrote in a letter to his sister-in-law that in that year he had sawed and cut a lot of wood, glued four thousand paper bags, and "also [made] many drawings, about 150 newsprint pages, which I gave away, however." Similarly, in the following year, 1907, only three are known, and they are in full color. In a letter to his sister-in-law that year he asks her to send him colored pencils, for "he was drawing industriously." Concerning a visit from his brother, he wrote to her: "I lured him on, with one of the drawings made by me, to be sure, one of the most beautiful ones I ever made." One of the three preserved color drawings from 1907 is „Felsenau“, Bern, which occupies a key position in the development from Wölfli's early pencil drawings to the color illustrations of the narrative work.

It was in 1907 that the first happy event occurred in Wölfli's dismal life: he met Doctor Walter Morgenthaler. After completing a practicum of several months as a volunteer psychiatrist in the Waldau Mental Asylum during that year, Morgenthaler returned to Waldau in 1908 and was active there until 1910 as an assistant physician and from 1913 until 1919 as head physician. He was supportive and encouraged Wölfli's work, which he documented during Wölfli's lifetime. In 1921 he published a pioneering monograph on Wölfli's life and work, “Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler” [„A mentally ill person as an artist“]. Never before had a patient been called an artist and his name been used in the title; even today such treatment is still most unusual in the fields of psychopathology and art.

When Walter Morgenthaler came to Waldau in 1907 he could see Wölfli's early drawings and read Wölfli's "Short life story" in the records. The questions he asked Wölfli about his life and his interest in Wölfli's past must have precipitated the drawing “Felsenau”. Wölfli probably received colored pencils from Morgenthaler, in whose possession this drawing remained. It shows the Felsenau textile mill and factory near Bern, and the surrounding countryside, as well as two extraordinary natural phenomena: the comet Coggia and the Northern Lights (which were both documented in the year 1870). The topography -- the factory site, the steep access road, the tunnel -- corresponds exactly to the local features. Wölfli knew the factory and the surroundings very well from his childhood, for he had lived with his mother in the neighboring Neubrück for a year (1870-1871).

The fruitful encounter between Wölfli and Morgenthaler had as its precondition Wölfli's persistent lonely work on the early drawings. The skill he acquired thereby must have given him his self-confidence as an artist. Wölfli took up the work of his narrative oeuvre in 1908, and he continued it without interruption until his death in 1930.

(Elka Spoerri)

“From the Cradle to the Grave” 1908-1912

Books 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 1A, 17

The eight Books of “From the Cradle to the Grave” contain a total of 752 illustrations drawn on newsprint in lead or colored pencil or oil crayon. They are not evenly distributed over the 2,970 pages of the Books. The largest portion of the drawings, done in 1910 and 1911, are bound in a tight sequence into Book 4. Wölfli drew many of the whole-page illustrations on large sheets, of approximately 100 x 75 cm and occasionally on even larger sheets, which he folded several times and inserted into the Book; these were similar to the panorama pictures popular at the time.

From 1908 on, Wölfli developed the most important motif of his formal vocabulary, the little bird (Vögeli), into its definitive form. The bodies of the birds are longish tubular shapes, with two feet in front. On the head is a point and an elongated oval mark shaped like a semicolon; the first could be an eye, the second, an ear (or mouth). These primal shapes with an eye, an ear, and a mouth can be read as hallucinatory emblems. They are also building blocks, fillers or symbols and serial elements that can be used to form larger figures. From 1908 till 1930, they occur in every one of Wölfli's pictures. They serve as a counterweight to the faces in Wölfli's work, which are marked by the impassivity and gravity of graven images. Drawn only in outline or filled with color, the bird appears coy and animated, standing still or flying, seemingly protective--never threatening--expressing excitation and sometimes danger. Very often the bird's body is filled with musical notes or interlocking bricks thus animating the brick wall and at the same time deanimalizing the bird by materializing the building.

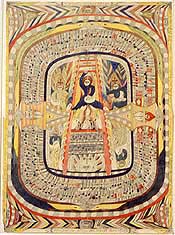

The whole-page illustrations with figurative compositions, labyrinthine buildings, eccentric landscapes, and city maps or mandala compositions refer to the content of the story. In the figurative pictures, Wölfli portrays his relatives and friends, as well as princesses, princes, and kings whom he meets on his travels, while consistently representing himself as the child Doufi. The figures are shown in individual and group portraits, in their daily life, dancing at festivities, in love embraces, and in scenes of sexual intercourse.

In spite of Wölfli's frequent descriptions of automatic clocks or mechanical objects, we find no representations of human figures composed of machine components (frequent in drawings by schizohrenics). There are, however many illustrations of anthropomorphic changes in vegetable beings, which are shown as "intelligent," "laughing," "flying," or "talking" flowers and fruits. For Wölfli, the flower motif is generally an image of female beauty. Flowers have girls' faces, and, for the most part, portray princesses. This simultaneous occurrence of "a catastrophe and an idyll" can be seen, for instance, in "Herdsman's Rose of Australia: Organs of Speech," in which the aura around the face (--the mezza-luna) of the Rose Princess is a knife. The petals of the flower around her head are arched windows in the first row and are transformed into barred prison windows in the second and third rows.

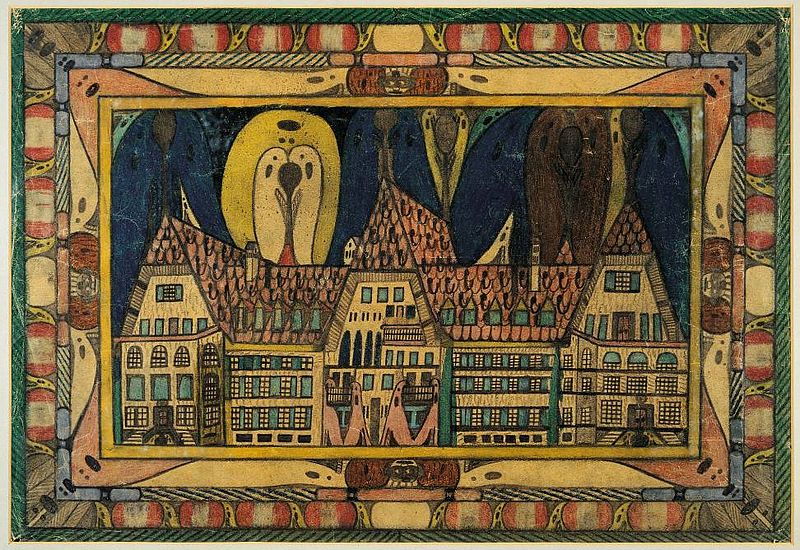

Architectural depictions--churches, towers, farmhouses, castles, monuments--become more prevalent as the story continues. Sometimes they are large and decorated with fantastic details. Whereas Wölfli, on the one hand, depicts windows very naturalistically, with curtains and wooden frames, at the same time, from the very beginning in l904, he can schematizes them in a very impressive way: rows of windows in long facades are drawn merely as short vertical lines.

As already mentioned, Wölfli's ideas of foreign places were clearly patterned on Bern. The topography of its Old Town outlined in the shape of a whale by the meanders of the river around it, the city's construction on two levels, the arches of the huge bridges, the street arcades and fountain sculptures, the cathedral, the clock towers, the bell towers--all serve as elements of Wölfli's renderings of faraway places and views. In one illustration in Book 4 he depicts a mental asylum, the Mental-Asylum Band-Hain in Greenland; yet he draws a bird's-eye view of the plan of Waldau. He must have seen the postcard of Waldau which was made from a photograph taken in 1907 from a balloon. This is one of the two instances known so far in which Wölfli followed a visual model. Usually he worked from memory or from the imagination.

The topographical drawings reverberate with echoes from Wölfli's childhood in the Alps. In 1908 he wrote about a panoramic view ("Feern-Sicht"), which is mirrored in his illustrations. Wölfli clearly enjoyed combining into a single drawing differing landscapes and topography that might come into view from changing positions in the course of a walk. He certainly knew the panoramic views and engravings of Swiss towns which were extremely popular at that time. Thus in the “Vue general de Berne. Vue prise de la Tour Goliath ou St. Christophe,” we find a combination of a bird's-eye view and a side view which recalls similar compositions by Wölfli. In the topographical maps and city plans Wölfli partly follows the school atlas he owned and used. But for the meanderings of rivers, the turns and twists of local streets and regional boundaries, he combines other entities: bodies of water swell into thick bands of blue and branch out like the boughs of a tree; portions of the landscape turn into objects, and fantastic conglomerations sometimes assume anthropomorphic features.

(Elka Spoerri)

“Geographic and Algebraic Books” 1912-1916

Books 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14

Adolf Wölfli "Poli-Chinelle, the Plum-Queen" 1912 |  Adolf Wölfli "Grammophon," 1915 |

The number-pictures (Books 6, 7, 8, 11 and 12) originate in the calculation of interest accruing from Wölfli's imaginary fortune. These number series reiterated in lead or colored pencil are most impressive in their design. The number-pictures reflect not only Wölfli's need for order but also his fascination with the incremental power of financial capital. The first part of Book 12 contains number-pictures that are frequently combined with figurative motifs fitted around the page as ornamental borders which depict Doufi's falls, execution scenes, or rows of figures and buildings. In the second part of Book 12 Wölfli writes number-pictures not only in numerals but also in words, using the names of his invented numerical system and sometimes combining them with portions of music notations.

The music-pictures exist primarily as musical notation, but some are combined with ornamental or figurative elements. They appear for the first time at the end of Book 11 in a series of fifteen drawings. The first seven are horizontal in format and resemble conventional music scores. In the following eight sheets Wölfli progresses to spiral or mandalalike vertical compositions. After the middle of Book 12 music-pictures increasingly replace number-pictures and they predominate in Book 13. Most of them are horizontal compositions with musical notations. Gradually the musical notations become activated: both the notation marks and the spaces between exist as entities and become readable, just as the positive and negative forms are. At first, the observer is puzzled by this interweaving of foreground and background elements. The interplay of light and dark and of interior and exterior realms seems complex and obscure. Executed in pencil, the dense fabric of notes produces a graying effect with the dull sheen of lead leaning toward darkness. In the vertical central axis of the compositions Wölfli gradually incorporates human figures: crucifixion scenes, coffins with dead people laid out in state, or series of crowned faces. These figurative elements executed in color intensify the overall impact of these pages. In Book 13 (1915) the first six collages appear in the spaces between the musical notation bands. Thus, Wölfli begins to fit pasted reproductions onto the pages instead of filling them with drawings. From 1916 on, in Book 14 the music notations disappear, replaced by solmization. Music-pictures do not appear in the Books after 1916; they can be found as parts of the “bread art” drawings from 1916-1930.

Another innovation of great importance occurs in 1915. Wölfli introduces a new motif into his vocabulary of forms: the eye mask. From 1912 onward, the glance looks sideways to the right, and thus the eye is divided into a black and a white shape. The black circles around the eyes get thicker and thicker and gradually close in the middle. Sometimes in these black circles around the eyes the eyelids remain visible as a white line. From mid-1915 on, this black shape spreads as far as the temples and comes to resemble a mask. This mask develops simultaneously with the music pictures of 1914-1916, just at the time when Wölfli was noticeably turning away from illustrative drawings and the figures were becoming ever more stylized. From 1916, the year he changed his name to St. Adolf II, the faces with the mask become Wölfli's emblem, leaving an indelible impression on the viewer. Toward the end of his life, from 1927 to 1930, the mask gradually disappears. In some drawings a gray veil is dispensed with altogether; the eyes are uncovered and look straight in front of them.

(Elka Spoerri)

“Books with Songs and Dances” 1917-1922

Books 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Adolf Wölfli "Great-Great-Imperial Family of the Pacific," 1917 |  Adolf Wölfli "Zungsang St.Adolf Roseli," 1917 |  Adolf Wölfli "Chocolat Suchard," 1918 |

In the Books of 1917-1925, the musical compositions are noted exclusively in solfège. The many repetitions of letters and syllables, the underlining of rhythm indicators, and the music signs themselves give the pages the visual appearance of decorative calligraphy. The decrease of narrative texts and drawn illustrations as time passes seems to indicate that Wölfli tired of the narrative work. In a forward in Book 20, titeld „Final Text“, Wölfli explains what hinders him from finishing his extensive narrative work: "The end. Esteemed reader and women readers, because of my painful disease and hideous further sufferings my undersigned humble person finds itself forced to directly conclude the great, instructive, entertaining and beautiful Book that should not be underestimated in any way in regard to its unfinished content; that should not prevent the eventuality of adding to the above-mentioned a number of meaningful, beautiful and memorable pictures, musical pictures, the musical execution of which I have sufficient energy and endurance to complete no longer. And yet after I have worked for 22 full years on this complicated oeuvre and have completed the third part of the whole Book, I should like to add to the aforementioned still another pretty final act, which certainly will give joy and pleasure to some musical genius. Here follows a beautiful, eleven-partite, Final-March-Blast, consisting of 11 songs. 1,922."

(Elka Spoerri)

“Album Books with Dances and Marches" 1924-1928

Album Books 1, 2, 3 and four untitled, unnumbered Books

In

spite of his announcement in the "Final Text" of 1922, Wölfli did not

stop writing and composing; he only changed the design and the manner of

illustrating the following eight Books. The Album Books have a

consistently horizontal format and are thinner and easier to handle than

the Books with Songs and Dances. The old continuous numbering of the

Books comes to a halt; only a few of the Books get a title.Four of these Books contain a middle part in which drawings done on good paper are bound. These Wölfli made for sale, originally they were series of 24 drawings. In their layout and format the Album Books recall standard picture albums. Evidently, in the design of these albums, Wölfli was at pains to bring the drawings into some relation with his narrative work. The added drawings are numbered on the back and provided with "Explanations," which refer only to the "preceding pictures" and not to the songs or texts of the albums. The texts are dated 1924 and 1925, whereas the drawings are from 1927 and 1928, when Wölfli evidently bound them into albums and titled them. The four Books without titles and numbers were probably also conceived as albums. No drawings are inserted into their midsections, but it is evident from the binding in the back of the cover that these once contained more pages, that is, that drawings previously contained in the Books were eventually taken out.

The texts and songs of the eight “Album Books” contain 201 pasted reproductions, which Wölfli titles Picture-Puzzles and numbers as a continuous series. In witty, mock-heroic verses of horror tales, he celebrates current events, personages, and places in Switzerland and abroad. The Federal Council, the Swiss army and technical innovations are some of his themes: "Picture-Puzzle, No. 40. Dissolved. The Coffeehouse National in Bern! That had a beautiful hall! Coffee now!! That I like! And I am not yet bald! I often think not of a distant place but of the beautiful Emmental! Up in the sky is glimmering a star! I am the Princi-pal. Is 16 beats, march. St. Adolf II, Bern."

(Elka Spoerri)

"Funeral March" 1928-1930

16 unnumbered Books

Adolf Wölfli "Campbell's Tomato Soup", 1929 P.3359 from "Funeral-March" |  Adolf Wölfli "The Rubber Wheel", 1929 P. 3482 from "Funeral-March" |  Adolf Wölfli Bon Ami, 1929 P.3604 from "Funeral-March" |

Wölfli's lapidary procedure of adding unchanged reproductions to illustrate the text allows us to understand which aspects of these motifs, detached from his own individual drama, had acquired an independent meaning for him. The reproductions he chooses document his rediscovery of the private world he has imagined and created, which he is then able to find in the world outside. His method of quoting his own narrative and visual themes by means of the found pictures creates a connection between his private life and public life at large. Through his use of magazine reproductions and his ability to locate his motifs in these pictures, Wölfli seems to open himself to the world. Nevertheless, he lifts these motifs out of the pictures only to take them, as it were, back into the "cradle."

(Elka Spoerri)

"Bread Art" - Single Sheet Drawings, 1912-1930

In

his monograph on Wölfli, Morgenthaler writes: "His production can be

divided in two big groups according to their purpose: one of which can

be called Bread Art. This consists of drawings which he makes for others

in order to get colored pencils, paper, tobacco, etc. . . . The other

group on which he himself places a much greater value comprises his

gigantic autobiography."

Adolf Wölfli "Hautania and Haaverianna", 1916 |  Adolf Wölfli "Packard", 1927 |

The single-sheet drawings are usually simplified and more schematic in their design than the freer multilevel illustrations in the texts. The figurative elements are limited to renderings of one or two persons. The frequent inclusion of wings gives them the resemblance of medieval representations of angels. The faces, ornate crowns recall tribal chieftains or extraterrestrial creatures; sometimes they wear a cross on top of their heads and suggest religious icons. They show very slight gender differentiation; one recognizes the males only by a moustache. The female figures usually extend their right arm across the left holding an object at waist level. Sometimes this object is utilitarian--a bass violin, a fan, an umbrella--but most frequently the hand is holding a bird.

The faces in the single-sheet drawings wear a kind of mask identical to those that appear on faces in the illustrations. This mask, second only to the bird, is the most idiosyncratic and therefore important form in Wölfli's work. Between 1916 and 1923 the portioning of the round opaque faces into parts covered by a mask and parts free of a mask reaches its full equilibrium, creating a volumetric sphere. Later on, in the drawings of 1926-1930, the mask gradually dissolves.

The birds increasingly become the dominant figures in the single-sheet drawings. They are the building blocks of whole compositions and eventually occupy the entire space; by the end, only the faces and the hands of the human figures are left free of them. They become so ingeniously melded that they can even be overlooked. They appear ordered in pairs, in rows, or in clusters, and their bodies are monochromatic or multicolored, frequently covered by stripes, cross-hatching, herringbone, or other patterns. With the compounding of face, wing, and bird shape, Wölfli succeeds in creating a new type of being, sometimes a human-bird, sometimes an angel-bird.

From 1908 until 1916 work on the „From the Cradle to the Grave“ and the „Geographic and Algebraic Books“ took up Wölfli's time. Morgenthaler reports that during these years, Wölfli did not respond gladly to the request to make drawings for other people: "Once in a while he gives away such a piece without asking to be paid to a person for whom he has a special liking, mostly to persons of the female gender or to children. But this does not occur too often; on the contrary, one frequently has to admonish him again and again to draw something for the benefit of others. Very often one gets the answer that he didn't have any time for it, that he had better things to do, etc."

The slowdown of work on the Books, which Wölfli had announced in the preface, called "Final Remarks" of Book 20, was probably caused not so much by the "painful illness" and the "horribly bitter suffering" he complains of as by public recognition; the demand for single-sheet drawings and in larger commissions increased after the publication of Morgenthaler's monograph. With some interruptions Wölfli was occupied from 1916 until 1921 with the decoration of two large wooden closets and two small vitrines at the Waldau Museum. The drawings are pasted on the large panels of the closets and in the smaller areas Wölfli drew directly on the wood. The museum was established in 1914 on Morgenthaler's initiative. In one of two low attic rooms above the auditorium in the new clinic objects of historical interest were amassed which had previously been used in the custodial care of the mentally ill, such as straightjackets, belts, covered bathtubs, and so on. In the other room drawings by Wölfli and by many other patients in Swiss mental institutions were stored. After Wölfli's death, all his Books were preserved inside the decorated closet, where they remained until their removal to the Adolf-Wölfli Foundation in the Museum of Fine Arts of Bern in 1973. During 1922 he worked on the four-part screen for Dr. Oscar Forel, each part 154 x 64 cm. On one side the four panels are composed of three drawings on each part, the four drawings on the other side are an example of Wölfli's ability and virtuosity in the creation of a unified large-scale composition.

Wölfli's self-assurance as an artist was demonstrated again in 1922 by his proposal of his own exhibition : a one-man show with a small catalog! Wölfli gives instructions and advises for setting the show provides financial help (needes still today – how could he know ?) : The annual excursion of the patients ended with an extensive meal, Wölfli wanted to show ten of his pictures. "And so I ask the highly honored Bären-innkeeper-family in Schüpfen, to frame each [picture] nicely and without fault and then to hang them on the walls of the ballroom. I send you these ten pictures as a voluntary gift. To cover further expenses, of course, for the carpenter and glass cutter, etcetera, and, if possible also for a gratuity for my efforts and the used material, I recommend to you to organize a collection for voluntary donations every time you have a dance; a marriage; a childs baptism; or any other kind of happy celebration. Why? That way you do not lose anything, and to some extent you would also do me a good turn. My advice is good and flawless; Believe me. But now, you should arrange it among yourselves, to buy about four or five, each, clean and fresh newspaper sheets, like this one here, in order to copy, that means, to transcribe the whole and entire text on the backside of the ten portraits, each according to their numbered order, as indicated below. This page presents the beginning or, the preface to the whole story. You should carefully photograph all ten pictures, and add these resulting though uncolored pictures to your respective explanations. Actually, you yourself could write a short final chapter about my Humble Self and, about Kirch-Dorf and the community of Schüpfen, etcetera. . . . So: have this whole story, nicely put together, printed perfectly in a printing press in Bern and, you have a rather pretty and instructive, amusing little book." („The Schüpfen Letter, 1922; unfortunately, the exhibition never took place)

In the same year, 1922, the schoolteacher Hermine Marti visited Wölfli in Waldau and became a true admirer and supporter of his art, commissioning and acquiring his works and paying generously for them. By 1930 she had a collection of forty-six works, including three pieces of furniture.

There are no texts in the narrative work dated 1923, although Wölfli made many drawings that year, especially for Hermine Marti. In 1924 and 1925 he made drawings and wrote the texts of the Album Books. There are no texts in 1926, for in that year Wölfli worked on some drawings and in particular on his largest picture, Memorandum, 3 x 1.5 m, which he executed on commission for the auditorium of the new clinic. The picture Memorandum represents a kind of compendium of Wölfli's motifs and themes, which in this large format he formulates on a grand scale with sovereign mastery and a sure feeling for the design of a mural. In 1926 he executed another large-size picture, San Salvatore, 202 x 149 cm, with an "explanation" of sixty-eight lines; it is his largest mandala composition, built up with strict orderings of birds and enclosed with a wide border of music notations.

Wölfli made his orders through the delivery man for Waldau. In 1929 he wrote: "Mr. Messer, bring me from the stationery store Kollbrunner in Bern the following colored pencils as listed here: 6. Cadmium, dark. 36. Scarlet red. 37. Saturn red 32. Crap-carmine. 47. English red. 49. Indian red. 52. Bister. 54. Burnt Umber. 46. Venetian red. 9. Orange. 14. May green. 26. Prussian blue, one piece of each, or, a total of 12 pieces. Yeah, also a whole bundle of black lead pencils, Kollbrunner No. 2, with the yellow wood. And one piece beautiful drawing paper, exactly 43 centimeter wide and 55 centimeter long."

(Elka Spoerri)

Adolf Wölfli

The Heavenly Ladder / Analysis of the Musical Cryptograms by Baudoin De Jaer (CD/BOOK)

CD + BOOK

52 full color pagesFrench + English

Contains only unreleased before material.

All tracks exclusively recorded for this project.

actually out of stock.

Baudouin de Jaer's approach gives a new dimension to the works of 20th century's major artists.

He had not been previously exposed to Wölfli's work. He was completely moved by the artistic and human dimensions of the mystery surrounding this gigantic and universal body of work created within the Waldau hospital in the early 20th century. He managed what none other had accomplished before: to decode Wölfli's hermetic and emblematic scores.

Adolf Wölfli

Adolf Wölfli (Bern, February 29, 1864 - Waldau, November 6, 1930)

was a Swiss artist who was one of the first artists to be associated with the Art Brut or outsider art label.

Wölfli was abused both physically and sexually as a child, and was orphaned at the age of 10. Institutionalized in 1895 at Waldau psychiatric asylum near Bern (Switzerland) where he spent the rest of his adult life. He suffered from psychosis, which led to intense hallucinations. Wölfli started drawing in 1899, but no work prior to 1904 has been preserved. In 1908, Wölfli started developing what would become a potentially endless narrative stretched across 25,000 pages interrupted only by Wölfli's death in 1930.

His images also incorporated an idiosyncratic musical notation. This notation seemed to start as a purely decorative affair but later developed into real composition which Wölfli would play on a paper trumpet.

After his death the Adolf Wölfli Foundation was formed to preserve his art for future generations. Today its collection is on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern and can be seen in many museums in the world. - Sub Rosa

Gelesen und vertont:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

Biography

Adolf Wölfli c. 1920 |  Adolf Wölfli in his cell next the stack of his books, 1921 |  Adolf Wölfli with paper trumpet c.1926 |

1864 Adolf Wölfli is born on 29 February 1864 in Bowil, Emmental (Canton Berne, Switzerland), the youngest of seven children of Jakob and Anna Wölfli-Feuz. The same year, the family moves to Bern. The father, a stonecutter, is an alcoholic. Wölfli grows up in dire poverty.

about 1870

Wölfli´s father abandons the family. The mother earns their livelihood as a washerwoman.

1872

Together with his ailing mother, Wölfli is resettled by the authorities is his home community Schangnau, in Emmental. The community takes over their financial support. Mother and son are separated and send to work at different farmers for food and lodging.

1873

Death of Wölfli´s mother.

1873-79

Wölfli lives as a hireling with several farmers in Schangnau under very hard working conditions and social degradation.

1880-89

He works as a farmhand in various locations in Emmental. A romance is forbidden and broken up for social reasons by the parents of the girl. Wölfli moves to Bern and works there and in the countryside of the Cantons Berne and Neuchâtel as handy-man and haycutter.

1883-84

He receives infantry recruit training in Lucerne.

1890

Wölfli is arrested for attempted sexual assault on two young girls (fourteen and five) and sentenced to two years in prison.

1890-92

He is imprisoned in the St.Johannsen prison in Canton Berne.

1892-95

Wölfli works as laborer in Berne and around in increasing social isolation and hardship.

1895

Wölfli is again arrested for attempting to molest a 31⁄2-year-old girl. In order to examine his mental accountability, he is commited to the Waldau Mental Asylum, near Bern, for evaluation. There he is diagnosed as a schizophrenic. He remains a patient there until his death in 1930.

1899

Wölfli begins to draw spontaneously.

1904-06

First preserved drawings forming a unified group and marked by high-quality draftmanship and artistic vision (pencil, fifty from presumably two hundred to three hundred drawings). Wölfli signs with "Adolf Wölfli, Composer".

1907

First preserved color drawings.

Walter Morgenthaler arrives as an young psychiatrist resident at Waldau, where he works, with interruptions, in different positions until 1919.

1908

Wölfli begins to work on his narrative oeuvre, which ends with his death in 1930 after 25´000 pages.

1908-12

Writes „From the Cradle to the Grave; Or; Through Work and Sweat, Suffering and Ordeals, Even through Prayer into Damnation. Manifold Travels, Adventures, Accidental Calamities, Hunting and Other Experiences of a Lost Soul Erring about the Globe; or, A Servant of God without a Head Is More Miserable Than the Most Miserable of Wretches.“ (9 books): Wölfli turns his dramatic and miserable childhood into a magnificent travelog illustrated by manifold color drawings.

1912-16

Writes „Geographic and Algebraic Books“ (7 books). In a series of testaments to his real nephew Rudolf Wölfli describes how to build the future „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“: a huge „capital fortune“ will allow Rudolf to purchase, rename, urbanize, and appropriate the planet and finally the entire cosmos. The textes (over 3´000 pages) are illustrated with number- and music-pictures.

since 1916

Wölfli signs his works „St. Adolf II.“ He begins the systematic production of his so-called Bread-Art, single-sheet drawings designed for sale, which he continues to make until 1930.

1917-22

Writes „Books with Songs and Dances“ (6 books): Wölfli celebrates his „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“ for thousands of additional pages, in sound poetry, songs, musical scales (do, re, mi, fa...), and collages.

1919

Walter Morgenthaler leaves Waldau at the end of the year. Dr. Marie von Ries becomes Wölfli´s new psychiatrist.

1921

Walter Morgenthaler publishes his monograph on Wölfli´s life and work „Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler“ („Madness and Art. The Life and Works of Adolf Wölfli“). In connection with the presentation of Morgenthaler's study, works of Wölfli are for the first time publicly exhibited in bookshops in Bern, Basel and Zurich.

1924-28

Writes eight books, among them four „Album-Books with Dances and Marches“ with musical compositions written in solfège and illustrated with drawings and collages.

1928-30

Wölfli writes the „Funeral March“, his requiem, which consists of 16 books with 8404 pages (unfinished). Wölfli recapitulates central motifs of his world system in the reduced form of keywords and collages, weaving them into a infinite tapestry of sounds, ryhtms, and pictures.

1930

Adolf Wölfli dies on 6 November of intestinal cancer.

1930-1975

Jean Dubuffet, the French artist and founder of „Art Brut,“ discovered the work of Adolf Wölfli in 1945 and called him „le grand Wölfli.“ The Surrealist André Breton considered Wölfli´s oeuvre „one of the three of four most important works of the twentieth century,“ and the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann showed a number of his pieces in 1972 at „documenta 5,“ the renown contemporary art exhibition in Kassel, Germany.

In 1972 the Adolf Wöfli Foundation was founded in Berne and since them, its collection is deposited in the Museum of Fine Art Bern. It contains the entire Wölfli estate as well as private gifts: 44 volumes of his writings, 6 notebooks and 250 single sheet drawings. The purpose of the Adolf Wölfli Foundation is to maintain, keep an inventary of Adolf Wölfli´s works, as well as to present his oeuvres to the public through exhibitions and publications.

|

||||||||

| For

somebody who's so biased towards classic music as I (nowadays) am,

world music should be a forbidden area. And believe me, I wouldn't

trespass into something that is so far from my minuscule competence

unless there was this: G'ganggali ging g'gang, g'gung g'gung! Giigara-Lina Wiiy Rosina. G'ganggali ging g'gang, g'gung g'gung! Rittara-Gritta, d'Zittara witta. G'ganggali ging g'gang, g'ung g'gung. Giigaralina, siig'R a Fina. G'ganggali ging g'gang, g'ung g'gung! Fung z'Jung, chung d'Stung.1 Many years ago on my way back home to Finlandia, I decided to check on the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern/Switzerland. It's a great museum in that even if the temporary exhibition turns out a failure, they have a meaty collection of Paul Klee there (as well as Kandinsky and Picasso). One of the best I know of in fact. |

|

|||||||

| So in I went. And came out ... well, a changed man. I had seen some of these paintings before in the Collection de l'Art Brut,

Lausanne. I had been browsing what Jean Dubuffet and Michel Thevoz had

written on their maker. But I wasn't prepared for this shock. I was

haunted. I saw about a hundred -- perhaps more -- paintings or drawings if you like, filled with circles, ovals, stars, notation lines, zigzag lines, spirals, squares (mostly not), small figurative spots etc. structured by means of horizontal, vertical and diagonal ornamental strips, animal forms, letter forms, geometric forms, mandala forms, the whole often framed with running decorative bands, sometimes symmetrically composed, but more often the compositional structure simply making way for the stupefying ornamental fireworks; largish, mostly pencilled on a brownish paper, some colored charmingly, some collages. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

It was great, extraordinary in fact, but I didn't know right off the bat what to think about it. I felt a helplessness that soon turned to irritation when my intellect worked out to say something but the mind was fed up with concepts and dull adjectives. Adolf Wölfli was a painter (1864-1930), a manic one at that with 1400 separate drawings, each of which would require a month's intensive work by an average person - plus 1500 collages. But he was also a writer and poet, with 20,000 hand-written and drawn pages in a series of vast hand-bound books; a mathematician creating his own algebra; and an explorer who made frequent trips to remote regions, which he describes in his Scientific Voyages, Hunting Expeditions, Casualties, Adventures, and other experiences of one gone astray on the whole earth globe; Or, a servant of God, without a head, is poorer than the poorest wretch, one of the many startling travel books he wrote. Wölfli was also a composer and musician. In one sense, music had a more significant role in his life and cosmology than images or words. He wrote songs, polkas, mazurkas, waltzes and marches in the style of folk music. He performed his music by blowing into paper horns whose sound contemporaries compared to country brass-band music. |

||||||||

| Wölfli

lacked any kind of musical training. That didn't prevent him from

writing a body of extraordinary musical scores. Notations with common

and mysterious signs appear in his numerous drawings and texts. The

canonical view has been that Wölfli's musical notes mainly serve

symbolic and decorative purposes but are musically illegible - "tending

toward, but not quite attaining, full musical sense" as one commentator

puts it. More recent studies show, however, that at least some of

Wölfli's scores make musical sense. Streiff and Keller, for example,

claim that his choice of musical pitches hardly was a matter of sheer

coincidence.2 |

|

|||||||

| There have been very few efforts to interpret Wölfi's music. A very rare LP Gelesen und vertont

exists in which this has been attempted. I'm a happy owner of one. It

tells much about the project's difficulty in that only a few purely

instrumental pieces have been included in the LP, the rest being more

like song poems. This doesn't matter, however, as in Wölfli's poetry

words were chosen not primarily for their meaning but rather their

rhythmic and sonorous effects. Words are split into syllables and

letters and then combined into often senseless neologisms. Rhythm and

repetition are essential to Wölfli's music - as well as art in general. |

||||||||

| In

addition to the LP, there presumably are only two CDs containing

Wölfli's music. In one of them, several experimental artists, fascinated

by Wölfli, pay tribute to the composer. The other is by Graeme Revell

who, based on the study by Streiff and Keller, creates his own

interpretation of Wölfi's music ["Necropolis, Amphibians & Reptiles -

The Music of Adolf Wölfli"]. Just like Wölfli's drawings and paintings have inspired many famous painters (e.g. Andre Breton), and his texts famous poets (e.g. Rilke), the musical undercurrent of Wölfli's art has stimulated many contemporary composers (e.g. Wolfgang Rihm, Per Nørgård and Terry Riley). One of the presentations in a recent Nordic Musicological Congress held in Helsinki was devoted to music brut and works based on Adolf Wölfli texts. Furthermore, some commentators have paid attention -- without claiming a causal connection -- to the fact that many of Wölfli's musical experimentations were explored in later 20th century music: folk music (Bartok), aleatoric music (Cage), birdsong (Messiae), graphic scores (Stockhausen) and architectonic ideas (Xenakis). |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Yes,

Wölfli was a schizophrenic. He suffered from hallucinations (voices)

and frequently behaved violently. Most of his adult life was spent in

Waldau, an asylum near Bern. It was there where his artistic career

developed slowly. There are many aspects of his art that have to be seen against his illness: his fear of empty space or dead time expressing itself in his hyperbolic use of numbers, music (melomania), words (logorrhoea) and images (iconophilia) and tending toward extension to infinity; the interplay of harmony (cosmos) and chaos (catastrophic destruction of the cosmos) etc. These are all means of reducing the anguish and holding one's identity together. It is therefore important to not to forget that Wölfli's music and art, just like his everyday life, are "ruled by the particularities of his paranoid thought" and "split" soul. Despite all this, it would be a misjudgment to refuse seeing the artistic value of Wölfli's creations. His drawings, for instance, have obvious aesthetic qualities which are easy to appreciate irrespective of the knowledge of his metal condition. Beyond this -- and without falling into the trap of romanticization and idealization -- one can also take Wölfli's work as confronting the essential questions of art and philosophy. What Wölfli is saying with his example goes deeper than the skin of his often complex and puzzling paintings, writings or compositions. |

||||||||

First, he teaches us genuine enthusiasm. I'm not talking about the obsessive behavior one frequently comes across in our audio hobby. I'm talking about the great seriousness and wholeheartedness with which he went about every project of his, the quotidian and spiritual being always united. In the Ancient Greek, "enthusiasm" meant "inspired by God". Perhaps that would do justice to Wölfli's unrelenting creative drive. What he accomplished has a certain true greatness in it, not that of the great men of the history books but of the potential for creative greatness in all of us. Secondly, he urges us -- again indirectly -- to dump many of those silly and small-minded distinctions with which we chain our life. No fear of being a dilettante, for example: "From now on the geographically described regions will be praised musically", he once wrote and so went for making music. No fear for showing child-like artistic impulses and so on. |

|

|||||||

| Raw art -- Art Brut or Outsider Art,

one of the greatest representatives of which Adolf Wölfli is now

acknowledged to be -- is sometimes defined as art which owes nothing to

tradition or fashion. A point is thus made on its divergence from the

institutions of fine or beaux arts; no pleasing of galleries, museums,

generally accepted tastes or any prior notions of what art is. But there seems to be more at stake here than the mere freedom from the culturally indoctrinated ways of doing art. It concerns itself over freedom from everything that is seeded in us ever since we were born, through socialization, cultivation and the massive whip of civilization. It is this freedom that seems to be intimately linked to the very process of creation itself and at the root of appreciating art in the first place. If Adolf Wölfli is to believed, to be free from all the inhibitions and social conditioning, one needs to turn one's eyes inward and listen to the deep music of one's soul. It is tempting to think that it is this fundamental music of our inner world that ultimately makes us appreciate the music of other people and cultures. Allen S. Weiss writing on Wölfli's magnum opus, The Funeral March, says: "We can never know the full meaning of The Funeral March, for it was sung by Wölfli alone, for Wölfli alone, a sort of autistic music. And yet, is it not precisely in such works that autism becomes communicative and that we reach the inner recesses of another's soul? Is it not only in such extreme cases that we can even begin to imagine the depths of another's soul, as well as of our own? How, indeed, do we sing? For whom? And against what?" ______________________________ 1 Allen S. Weiss, Shattered Forms, Art Brut, Phantasm, Modernism, State University Of New York Press, 1992. This story has benefited from the insights given especially in the chapter "Music and Madness". 2 Peter Streiff and Kjell Keller, Adolf Wölfli, Composer, in Adolf Wölfli (Adolf Wölfli Foundation, 1976) |

||||||||

The Far SideAn outsider artist’s scary grandeur.by Peter Schjeldahl

Adolf Wölfli, a Swiss madman, born in 1864, who spent the

last thirty-five of his sixty-six years in a psychiatric hospital, is among the

greatest of outsider artists. Indeed, he could serve as Exhibit A in a study of

the outsider phenomenon: cases of wild, solipsistic genius that challenge the

values of formal training and cultural initiation, not to mention sanity, in

significant art. Spectacularly gifted outsiders, including Henry Darger, a

Chicago janitor whose immense epic of a war involving little girls came to

light after his death, in 1973, seem to represent an entire culture in a single

person. So it is with Wölfli, whose large, incredibly dense drawings combine

religion, sex, language, music, geography, economics, and other aspects of the

artist’s fantasy empire, which, for him, was more or less the universe. His

achievement is a revelation in “St. Adolf-Giant-Creation,” a retrospective at

the American Folk Art Museum. The works’ aesthetic refinement is amazing. I had

known Wölfli mainly from reproductions, which cannot convey his virtuosity.

Especially in his earliest surviving pictures—from 1904 to 1907, after the

staff at the Waldau Mental Asylum stopped regarding his work as “stupid

stuff”—he emerges as, among other things, a master of graphic design with an

exceptional talent for tonality.

“Waldorf Astoria Hotel” (1905), to take one example, is a

pencil drawing on four sheets of newsprint, about ten feet long. It imagines

the eponymous hotel and three others (which Wölfli knew about from magazines)

as elaborate palaces, embellished by ornate borders, sinuous patterned bands,

exfoliating decorative motifs, cameos of enigmatic faces and figures, and

passages of fancy block lettering and handwriting. The composition is

jam-packed, but it doesn’t feel congested or fussy. Its complex linear rhythms

carry beautifully throughout the multipanelled format. One reason is Wölfli’s

command of finely textured blacks and feathery grays that, experienced as

colors, affect the eye as musical timbres do the ear. Inch by inch, the tones

subtly advance and recede, knitting together a shallow visual space somewhat

like that of classic Cubism. Looking at it stirs tumbling and gliding

sensations. One falls into the work’s bizarrely scaled, phantasmagorical

topography like Alice down the rabbit hole. And, like Alice, one may be less

than reassured by the charms of the experience, which is seriously disturbing.

Wölfli, who was born near Bern, was the seventh son of an

alcoholic stonecutter who abandoned his family to dire straits when the boy was

five years old. From the age of eight, after his mother died, Adolf worked for

room and board with a succession of sometimes abusive farm families. He did

well in school, but left at the age of fifteen. At eighteen, he fell in love

with a farmer’s daughter and was shattered when her parents forbade her to

marry so lowly a suitor. Pain and rage at this humiliation seem to have

possessed him for the rest of his life. He served in the Swiss military, had

affairs with a young prostitute and a much older widow, and held a series of

menial jobs. He was arrested twice for petty theft. He became a predatory

pedophile, and was caught three times while trying to molest ever younger

girls: fourteen, seven, and three years old. He escaped arrest for the first of

these crimes and spent two years in prison for the second. The last offense

landed him in Waldau in 1895. He was dangerously violent for some years—at one

point, he bit off a piece of a fellow-inmate’s ear—until his energies became

wholly absorbed in drawing, writing, and musical composition.

Wölfli wasn’t much more than five feet tall, but in

photographs he is formidably tough-looking, with bulging muscles, a bristling

mustache, a tobacco plug in his cheek, and a taciturn stare: a man with a

mission. He couldn’t stand to be contradicted. (For example, he became agitated

whenever it was pointed out that his abundant composition of polkas, mazurkas, and

other folkish music—which he would play with a horn of rolled-up paper—was

notated on absurd six-line staffs.) His desperate need to work made him

somewhat tractable. He was kept on a ration of one or two pencils a week until

1907, when a psychiatrist named Walter Morgenthaler arrived at Waldau and took

an interest in him. Colored pencils were added to Wölfli’s tools. Though his

use of color is often strikingly original, it tends to disrupt the unity that

he achieved with shading alone. His work increasingly centered on

megalomaniacal illustrated books, which total about twenty-five thousand pages

of story, rant, and poetry. Among the recurrent visual motifs are mandalas,

eyes, hieratic faces, vaginal forms with tiny clitoral accents, and a versatile

shape that is readable as, alternately, a slug, a bird, and the head of a

snake. Some later works—collages of scrawled nonsense poems, magazine

photographs, and advertisements (including, perhaps, the artistic début of

Campbell’s soup)—feel uncannily intelligent. They amount to oracular

experiments in graphic semiotics.

In 1921, Dr. Morgenthaler published a monograph on Wölfli;

shortly thereafter, a pioneering book on the art of the insane, by the

psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn, which included a discussion of

Wölfli, excited Surrealist circles in Paris. Carl Jung was among the collectors

of Wölfli. The artist responded to commercial demand with smallish, one-off

drawings that he contemptuously termed “bread art.” Many are lovely, suggesting

a brawny Paul Klee. In the nineteen-forties, Jean Dubuffet featured Wölfli in

his promotion of “art brut”—creative expression by society’s outcasts. In 1965,

André Breton called Wölfli’s production “one of the three or four most

important oeuvres of the twentieth century.” There’s an antique air now to such

encomiums, which evoke modern beliefs in the superior authenticity and possible

revolutionary portent of “primitive,” childish, criminal, and otherwise

anti-rational impulses. Things being as they are in the world at present, we

may be hard put to conceive of reason as an obnoxious obstacle to human

fulfillment. Anyway, Wölfli wasn’t anti-rational. He was nuts.

Outsider art enjoys little favor these days in the

professional art world, where the right to be crude, weird, and nasty is

reserved for artists with master’s degrees from leading art schools.

Sophisticates caricature a taste for outsider art, with some empirical justice,

as a sign of patronizing sentimentality and populist resentment. But the

intransigent grandeur of a Wölfli calls everybody’s hand. He seems to be at

least as troublesome for outsider fanciers as for vocational élitists. Besides

having an immensely complicated and subtle technique, Wölfli is scary. Trying

to make a pet of him could get your hand bitten off. The ornate, hieratic

majesty of “The San Salvador” (1926), a drawing nearly five feet high and more

than seven and a half feet long, dazzles at first glance, but becomes more

disquieting the longer you look. Within a wide border full of musical notation

and heraldic and geometric motifs, an eyelike oval of concentric bands,

featuring sinister red-tinted bird shapes, encloses a targetlike mandala. A

scepter-wielding, devilish African personage presides in the middle; he is

flanked by other, equally daunting African faces—the palace guard. The picture

projects absolute, malign power.

The common critical deprecation of outsider artists as

hermetic obsessives, like birds fated to repeat their single songs, does not

apply to Wölfli, whose work is robustly varied and subject to development,

however odd. (Come to think of it, many a fine artist has won admission to the

modern canon with an obsessive, essentially unchanging manner.) To do Wölfli

justice—that is, fully to honor our spontaneous pleasure in his work—requires a

bravely open mind. That virtue is well served by the admirable American Folk

Art Museum, whose Wölfli show, curated by Daniel Baumann and the late Elka

Spoerri, exemplifies the museum’s exacting connoisseurship of outsider art

along with traditional quilts, whirligigs, and other relics of demotic

innocence. (It runs until May 18th.) Having already shown Darger, the museum

has tentative plans for a retrospective of my own favorite outsider, the

Mexican psychotic Martin Ramirez (1885-1960); his graphic repertoire of

womblike tunnels and noble prosceniums shows a startling affinity to Wölfli’s

style.

Maintaining a strictly aesthetic sensitivity to Wölfli is

difficult, but I think it’s worth a try. It involves resisting various mental

habits with which we police the frontiers of our sanity and our morality. At

one extreme is political correctness, which is apparent in the fashionable

euphemism for outsider artists as “self-taught.” As if any true artist were not

self-taught! (Picasso didn’t learn his stuff at Picasso School.) Such misguided

compunctions blunt the jagged, tatterdemalion otherness that is central to our

experience of a Wölfli, a Darger, or a Ramirez. Then there’s the medical model,

which, confusing appreciation with diagnosis, exploits outsider art (or

Michelangelo, for that matter, in the case of Dr. Freud) to show off the tricks

of a rote methodology. Psychoanalysis seems increasingly passé, of course, now

that psychiatry has gone chemical. Today, potential Wölflis are apt to be mute

and inglorious, their explosive minds defused by clever drugs—in line with a

recent ethical imperative that sets the relief of suffering above any rival

value. Between one thing and another, the unruly garden of outsiders has become

as diminished and as endangered, though as perilous to susceptible tourists, as

virgin wilderness.

|

||||||||

Algebra Is Drunkenness

Allen S. Weiss

Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930), arguably the most famous of schizophrenic artists, describes his smallest diamond as weighing 28 million tons.1 Its value is incalculable (though Wölfli never hesitates to calculate the unthinkable, covering pages and pages with giddy computations), its weight crushing (but isn’t this already a triple source of power: financial, aesthetic, physical?), its possession megalomaniacal (the sort of cosmic hyperbole that characterizes much art, theology, paranoia). Here, the imagination overcompensates for a state of nearly total social dispossession and psychological disequilibrium. The fantasy of such a diamond is a strategy of survival and a trace of creative joy in an otherwise bleak universe. It stands for ecstatic proliferation, a numerological dream of order-within-chaos, an intoxication of the mind by the mind.

There is a poetics of the ad infinitum, a self-hypnosis founded on the charms of parataxis raised to the power of infinity. As such accumulations reach the point of the incomprehensible, they transform aesthetic sentiments: we call this cognitive disarticulation, and dissonance the sublime. What the golden section is to beauty, the infinite is to the sublime. The very large or very complex, for most intents and purposes, serve as tantamount to the infinite, and given the representational limits of human knowledge, attempts to emblematize the incommensurable take refuge in the implication, rather than the description, of enormity. Symbols for the limitless—that which is above all calculation—may be variously constituted by the fingers of one hand, or two hands, or two hands plus two feet, or a specific figure like the numerical value of God [18] in Jewish symbolism, or the ten thousand things of Chinese philosophy, or the disconcerting trente-six [36] that the French use to designate great quantities. The essence of the sublime thus changes with every culture and every epoch; perhaps ours has become the streaming 01010 of digitalization, or the ACGT strings of nucleotides that comprise all DNA. Entrapping the absolute within quantifiable confines seems to have perennial charm, and the fact that digitized or genetic code touches on a reality that can be measured and verified, while Wölfli’s diamond cannot, does not alter the fundamental poetic link between them.

A contemporary master of the mathematical and molecular sublime is New York artist Melvin Way, whose drawings of chemical and numeric equations celebrate the ecstatic power of self-propagating structures. Way’s obsessive inscription is a picture of calculation, not calculation per se; in his art, both the formal lineaments of scientific notation and the limits of the infinitesimal sublime are revealed through their aesthetic simulacra.

As such, Way’s drawings constitute a rare manifestation of the mathematical sublime as black humor, the acerbic and hermetic humor of the dispossessed. In these works, where drama is couched in the form of arcane formulas, calculation = sublimation, spectacle = performance, equation = icon, prescription = representation. Way has been classified as an “outsider” artist; we might wish to revive the 19th-century category of the poète maudit to further refine this qualification—though it is the milieu, rather than the artist, that should properly be termed “accursed.” In a cruel world where surviving urban chaos is—especially for the disenfranchised—often a matter of chemical reactions (recreational or medicinal), and where there is a constant danger of viral infection (biological or cybernetic), the best protection from imminent catastrophe may be that strategy of first and last resort, the imagination. Formulas are used to control the world, not unlike magic spells. Might not the work of Way contain a phantasmatic pharmacopoeia that offers homeopathic cures for real addictions and pains? In Way’s world, exclamation is interruption: his counting and calculating, his “math” and “chemistry,” shock us into the recognition that what connects (indeed, what constitutes) us all is the unspeakable complexity of numbers and atoms, chemical reactions and genetic structures—the infinitesimal side of infinity that theologians after Pascal have so hazardously neglected.

Wölfli insisted that “Algebra is music,” and Baudelaire that “Drunkenness is number.” We have known, ever since Pythagoras, that music is number, and that the music of the spheres is a sort of celestial algebra. To further factor out this aesthetic theorem, we might add that Melvin Way reveals the converse: algebra is drunkenness.

- The critical literature on Adolf Wölfli is vast; one of the most inspiring studies is by Harald Szeemann, “No Catastrophe without Idyll, No Idyll without Catastrophe,” in Elka Spoerri, ed., Adolf Wölfli: Draftsman, Writer, Poet, Composer (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 124-135.

Primal Time

Ecstatic Shamanic Devices at the Folk Art Museum

It is said that through some sort of mystic cabalistic jujitsu, when

all 666 names of God are spoken, the world will end. Over the millennia,

artists, writers, philosophers, and musicians have revealed some of

these names. Certainly, the mighty Swiss "outsider artist" Adolf Wölfli

enunciated a handful of them in his fulminating, mandala-like

illuminations, drawings, and collages—105 of which are on view in the American Folk Art Museum's

enthralling survey, "St. Adolf-Giant-Creation: The Art of Adolf

Wölfli." These powerhouses of energy are as magical as they are

aesthetic. Two-dimensional passageways for metaphysical travel, they are

visual magic carpets capable of transporting viewers to varied psychic

dimensions. The best of them are ecstatic shamanic devices. Perhaps

sensing this, surrealist potentate André Breton grouped Wölfli with Picasso

and Gurdjieff as among the era's most inspirational figures,

pronouncing him "one of the three or four most important artists of the

20th century." As with most things Breton, the claims are overblown. But

not by much. And springing Wölfli from the outsider ghetto was

prescient.

Still, no doubt about it, Wölfli was deranged. Born in 1864 in Bern,

he was abandoned by his alcoholic father at five. Three years later,

his mother died and Adolf became a hireling. In 1882, in a heartbreaking

incident that "haunted him for the rest of his life" (according to Elka Spoerri,

the late, great Wölfli scholar who co-curated this show), 18-year-old

Adolf fell in love with a farm girl whose parents forbade her ever to

see him for "social reasons." In his autobiography, he lamented, "I

became downcast, even melancholy, and was at my wit's end. That same

evening I rolled in the snow and wept for the happiness so cruelly

snatched from me . . . my heart had suffered too much." Then he

unraveled.

In 1890, Wölfli was convicted of attempting to molest a seven-year-old girl and sentenced to two years in prison. Five years later, he was arrested before he could molest a three-year-old girl, and was sent to an asylum in Bern, where, diagnosed as a schizophrenic, he spent the remainder of his life, dying there in 1930. The decisive moment in Wölfli's artistic life occurred in 1899, when, after four years of "extreme agitation," he started drawing.

He never stopped. By the time he died, he had produced a massively fantastical body of work consisting of 25,000 pages of richly illustrated text, 1,620 graphite and colored-pencil drawings (many of himself and his lost love), and 1,640 collages. All were preserved by his extraordinary doctor and biographer, Walter Morgenthaler. Stacked in a pile, this Blakean, biblical ur-work towers 10 feet high.

Wölfli's masterpiece is divided into five books. Every page is carefully numbered; drawings are folded, tipped in, and can be as large as four-by-four feet. The narrative brims with cataclysm, pandemonium, and redemption (not unlike Henry Darger's "Vivian Girls" epic). The first book is titled From the Cradle to the Grave, and is Wölfli's imaginary, grandiose autobiography. Many of his basic forms and motifs are already in place: masked faces, bells, birds, buildings, snakes, snails, and musical notation; curlicues, cross-hatching, dots, and spirals. In the next volume, Geographic and Algebraic Books, he takes off into the realm of myth, recounting his travels through the universe, and his own transmutation into what he dubbed the St. Adolf-Giant-Creation. In this book, Wölfli calculates his vast accumulating wealth in cascading columns of numbers. He then celebrates his almighty status in drawings, songs, polkas, and marches in the next three books, including the 16-part, 8,404-page Funeral March.

Wölfli is often compared to Darger. But Wölfli is a more dogged and abstract artist than Darger. He's more primal, less pictorial, less winsome. Early on, Morgenthaler noted the horror vacui, or fear of open space, in Wölfli's work. Indeed, there are no panoramas or large-scale figures in his art. There's also almost no space, light, or graspable narrative—only undulating, churning surfaces, which are often so jam-packed they can be difficult to look at. Everything is stylized, divided, and small; images oscillate and seem unstable. Yet in many of these drawings, everything whirls together in a rapturous, madly lyrical visual fever dream.

Wölfli has long been a favorite of the art world. Starting in 1921, he's had museum retrospectives in Germany, Great Britain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.S., and is often referred to as "one of the greatest outsider artists." If forced to judge him by this designation, I'd place Wölfli behind only Martin Ramirez and Bill Traylor, and just ahead of Darger. But it's time to get rid of this term, along with whatever labels we use to keep certain artists in their place. Regardless of his mental condition, Wölfli's art is universal. By now, almost everyone would agree that the work of Agnes Martin or Donald Judd is no more "inside" than Wölfli's or Darger's. In fact, painting grids or making boxes for a lifetime is as out-there as drawing the cosmos.

photo: Robin Holland

A two-dimensional passageway for metaphysical travel: Adolf Wölfli's drawing The St. Adolf Ring of Oberburg (1918)

In 1890, Wölfli was convicted of attempting to molest a seven-year-old girl and sentenced to two years in prison. Five years later, he was arrested before he could molest a three-year-old girl, and was sent to an asylum in Bern, where, diagnosed as a schizophrenic, he spent the remainder of his life, dying there in 1930. The decisive moment in Wölfli's artistic life occurred in 1899, when, after four years of "extreme agitation," he started drawing.

He never stopped. By the time he died, he had produced a massively fantastical body of work consisting of 25,000 pages of richly illustrated text, 1,620 graphite and colored-pencil drawings (many of himself and his lost love), and 1,640 collages. All were preserved by his extraordinary doctor and biographer, Walter Morgenthaler. Stacked in a pile, this Blakean, biblical ur-work towers 10 feet high.