Chris Marker o Medvedkinu je napravio dokumentarac Posljednji boljševik, no njegov nijemi film Sreća satira je i možda prvi sovjetski "postmodernistički" film.

Like many cinephiles I became familiar with Alexander Medvedkin’s work through Chris Marker’s wonderful documentary, The Last Bolshevik, that featured a tender portrait of the topsy-turvy Soviet director. I emphasize “Soviet” as I was continuously astounded as to how Medvedkin got away with his earnestly over-determined socialist sketches that equated Soviet modernity with naïve folk culture. Some of the images from Medvedkin’s 1935 filmHappiness really stood out in Marker’s essay with their striking iconography and ridiculous approach to socialist realism. The film style borrows heavily from slapstick, farce and surrealism but in a highly original combination. Medvedkin was an ambivalent character and appeared to enjoy an absurd sense of humour at a time when few people were making jokes. This stylised folk tale is a witty satire on the Soviet system and perhaps the earliest example of Soviet postmodernism.

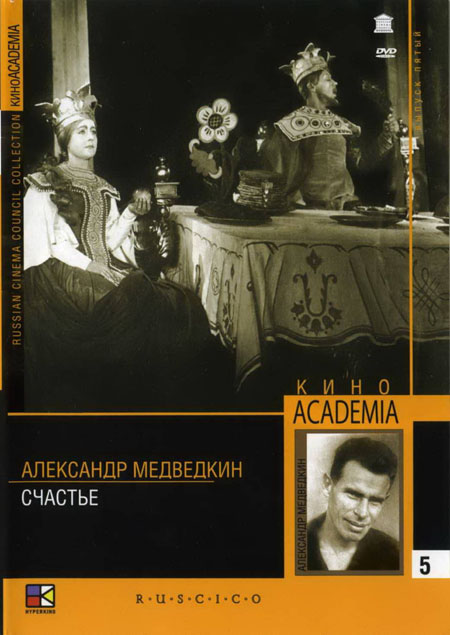

Happiness was released on DVD by RUSCICO as part of an Academic series that features both Soviet silent and early sound films. This edition makes use of an innovative form of cinematic hypertext, the Hyperkino feature, which mixes the director’s remarks and scholarly footnotes. The notes appear as numbers on the top right providingconsiderable commentary and illustrations for selected scenes, or background to various characters and inter-titles. Films like Happiness operate on multiple levels, and these scholarly notes provide great insight to the background,production and context of the film. I suspect they would be invaluable to students of the period. The Hyperkino system was developed by Nikolai Izvolov and Natascha Drubek-Meyer, and is best experienced on a computer where the viewer can really take advantage of the interactive options on the disk and read the notes with greater ease. The well-designed package thoughtfully includes two region-free disks: Disk One features the film with the Hyperkino commentary in Russian and English and Disk Two which includes the film with a choice of subtitles (English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese). Furthermore, the high transfer and image quality of the DVDs is impressive.

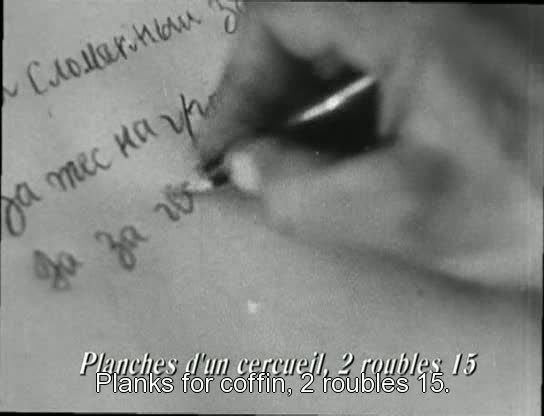

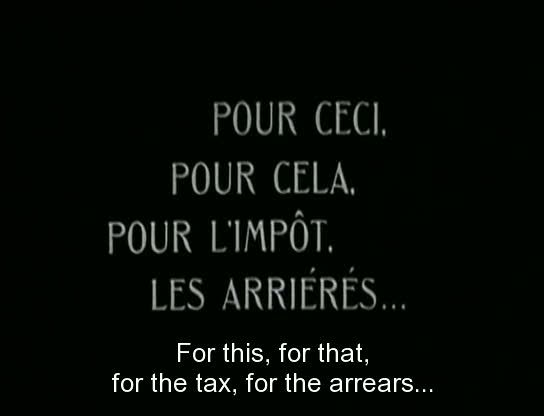

Happiness is a quirky, philosophical comedy in both form and content. Its characters, themes and style originate from Russian folklore but the film is charged with a risqué, modern humour that crafts a funny yet bleak portrait of peasants in the 1930s. It is a tale about a poor, hapless and lazy peasant called Khmyr who is sent out by his wife, Anna, to find happiness. As in a typical Russian folktale he expects it to fall upon him from the sky as a miracle rather than through hard work. Khmyr and his wife are dirt poor, and in Russian folklore, the poorer the peasants the more they were apt to believe in miraculous salvation. One form of happiness resides right next door where a neighbour enjoys an endless amount of pastries as they jump straight out of the frying pan and into his mouth. Khmyr’s idea of happiness is manifest in his dreams of being tsar, eating and doing nothing all day. He needs a miracle, and soon finds one in the form of a merchant’s purse by the side of the road. The money seems to grant him and his wife happiness, but it’s temporary-the tax collectors take all of their newfound. Then a group of thieves attempt to rob Khmyr, but when they discover that he has nothing, they give him money out of pity. Dejected, Khmyr decides to take his own life, however the bureaucrats need workers, and they send soldiers to beat some sense into him. After the beating Khmyr loses all hope for happiness, but his industrious wife, Anna, finds real happiness on a collective farm.

Naturally the satire operates in story-time, and there is an easy transition between the pre-revolutionary past and the Soviet present. This grotesquely funny parody of collective farming was filmed in the style of the Russian folktale in a representational mode. It confused the critics and was banned by the authorities for twenty years after it became apparent that Medvedkin was ridiculing the collectivization policy. With the rising popularity of the talkies Happiness became the last silent film of the Soviet era. Happiness is a rich and complex parable, and the newly released edition by the RUSCICO Academia series offers extensive supplementary notes and background information, which significantly enhances the viewing experience. The context provided affords a greater understanding and appreciation for the film, and the new release brings the work of Medvedkin to a new and broader audience. - Greg Dolgopolov

Aleksandr Medvedkin’s Happiness, as rowdy as any Soviet silent movie, is a comic parable composed of equal parts of Tex Avery and Luis Buñuel. It satirizes the plight of a Soviet farmer who finds himself providing for the state, the church, and his peers at the expense of his personal satisfaction. A hapless young prole, Khmyr, is tasked by his wife with the goal of going out in the world and finding happiness, lest he end up dead and dissatisfied after a lifetime of toil, like his father. Through stylistic exaggeration and a systematic attack on pre- and post-Revolutionary Russia’s dearest institutions, the movie achieves a wide-ranging, and deeply wounding, attack on the limitations placed on personal freedom in Russian society. - sovietmovies.blogspot.com/

"Go and find happiness.”

It is now generally accepted that if not for the efforts of another less talked about filmmaker Chris Marker, the world may not have come to know about his mentor Alexandr Medvedkin and his work. Standing somewhere between the films of Dovzhenko and those of Pudovkin, Medvedkin’s most famous movie Happiness (1934) offers a radically different perspective to the political and cinematic developments in Stalinist Russia. The discussions about Soviet cinema have been dominated by the films and theories of major figures like Eisenstein and Vertov, and perhaps rightly so, obscuring inevitably other stalwarts who may have been. Much less a theoretician than his contemporaries, Medvedkin produces a film that may never make it into classrooms. But one thing can’t be denied and that is the fact that Happiness is a film with a heart. Happiness does work very well as a stand alone piece, but the fact that it is a culmination of a larger and a nobler mission makes it all the more special.

It is now generally accepted that if not for the efforts of another less talked about filmmaker Chris Marker, the world may not have come to know about his mentor Alexandr Medvedkin and his work. Standing somewhere between the films of Dovzhenko and those of Pudovkin, Medvedkin’s most famous movie Happiness (1934) offers a radically different perspective to the political and cinematic developments in Stalinist Russia. The discussions about Soviet cinema have been dominated by the films and theories of major figures like Eisenstein and Vertov, and perhaps rightly so, obscuring inevitably other stalwarts who may have been. Much less a theoretician than his contemporaries, Medvedkin produces a film that may never make it into classrooms. But one thing can’t be denied and that is the fact that Happiness is a film with a heart. Happiness does work very well as a stand alone piece, but the fact that it is a culmination of a larger and a nobler mission makes it all the more special.

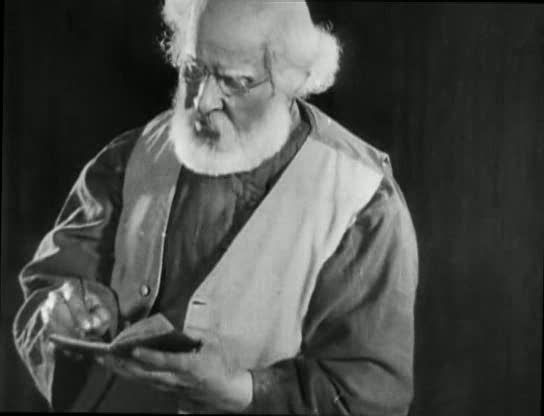

Happiness follows the life of a poor Soviet farmer Khmyr (Piotr Zinoviev) and his “horse-wife” Anna (Elena Egorova) before and after the October Revolution. During the Tsar’s rule, we see Khmyr struggling for existence and envying his wealthy neighbour Foka, who also happens to be the loan shark of the village. So he goes in search of happiness and gets it in the form of a sum of money. He buys a horse for farming but the animal goes on a strike. He manages to harvest by substituting Anna for his horse and gathers a rich output. His celebrations don’t last long as Foka and the Church figures are quick to grab it back from him. He contemplates suicide, but the Church prevents him from doing this “sin”. Now, it decides to punish him by whipping him but not allowing him to die. Years pass by and the country is now in the hands of the communists. The collective farming system has been implemented. Anna seems to have adapted to the system and seems to be doing exceptionally well, becoming the breadwinner of the family. Khmyr, on the other hand, lazes around, making one blunder after the other, desperately tries to become an honest farmer. But the disinvested Foka plans revenge.

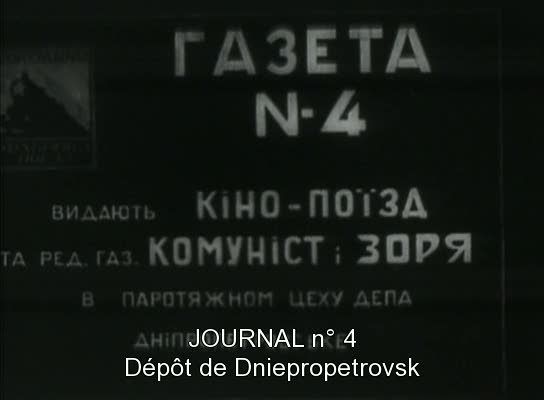

Happiness would seem like a very directionless film, if one does not take a look at Medvedkin’s modus operandi outside of the film. Medvedkin was one of the founders of the famous Cine Train of Bolshevik Russia that aimed to travel into the hinterlands of Russia, document the lives of peasants and workers and show it back to them in order to make them understand their strengths and weaknesses. The country had just entered the Bolshevik regime and the common folk, it seems, found it difficult to adapt to most of the improvement measures. Medvedkin and group understood this problem and used the cinema as a medium of introspection to illustrate the situation clearly to the people. Be it public service messages like the importance of hygiene (as in the film Watch Your Health), critical documents about absenteeism, inefficiency and negligence (as in Journal Number 4 and The Conveyor Belt) or queries for betterment of living and working conditions (How Do You Live Comrade Miner?), the Cine Train seems to have never hesitated in putting everything that is right and everything that is questionable about a system on the same plane. And that is very true about Happiness too.

Joseph Stalin banned the movie apparently because he thought that Happiness was mocking his collective farming system – the Kolkhoz – but spared Medvedkin knowing his service for the state. But surely, what Medvedkin was doing was neither a satire on the state of affairs nor a propaganda movie that the Soviet cinema was famous for. What he was presenting was merely an honest view of the newly born farming system, without any form of prejudice or support. For this, Medvedkin pays equal attention to both the positive and the negative ramifications of the collective farming. Through a largely objective eye – a common eye called cinema – Medvedkin makes a transparent reading of the Kolkhoz, its strong points and its limitations. If Stalin is pleased by Medvedkin’s attack on the exploitative and irrational nature of the church in the Tsar’s regime, he would be turned off by the vignettes of the Kolkhoz, where there are a bunch of goons waiting to ruin it all for themselves. If he would be laughing at the director’s depiction of the Tsarist army as a bunch of men wearing the same grumpy plastic masks, he would be annoyed by the possibly individualistic upshot of the film. But by no means is Medvedkin taking a centrist stance, for his stance is that of the people. As confirmed by Happiness, his interest is not the upholding of a political ideology, but a desire for people to have better lives.

Joseph Stalin banned the movie apparently because he thought that Happiness was mocking his collective farming system – the Kolkhoz – but spared Medvedkin knowing his service for the state. But surely, what Medvedkin was doing was neither a satire on the state of affairs nor a propaganda movie that the Soviet cinema was famous for. What he was presenting was merely an honest view of the newly born farming system, without any form of prejudice or support. For this, Medvedkin pays equal attention to both the positive and the negative ramifications of the collective farming. Through a largely objective eye – a common eye called cinema – Medvedkin makes a transparent reading of the Kolkhoz, its strong points and its limitations. If Stalin is pleased by Medvedkin’s attack on the exploitative and irrational nature of the church in the Tsar’s regime, he would be turned off by the vignettes of the Kolkhoz, where there are a bunch of goons waiting to ruin it all for themselves. If he would be laughing at the director’s depiction of the Tsarist army as a bunch of men wearing the same grumpy plastic masks, he would be annoyed by the possibly individualistic upshot of the film. But by no means is Medvedkin taking a centrist stance, for his stance is that of the people. As confirmed by Happiness, his interest is not the upholding of a political ideology, but a desire for people to have better lives.“Every man is seeking happiness. Some see it in wealth, but the Russian peasant who struggled in poverty dreamt of it in his own way. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov noted in his diary: “What is a Russian peasant’s dream? If I were tsar, I’d steal 100 roubles and run away!” A Russian proverb says that the peasant’s reply is: “If I were tsar I’d eat the fat of the bacon and I’d go to sleep.” What an idea of happiness! Just having a piece of bread, not being hungry, having a horse, a barn, having a few possessions, a sack of wheat… Such an idea of happiness, so little, but linked to the age-old harshness of a Russian peasant’s life, that’s the basis of my comedy Happiness. I tried to show the tragedy of such a man, and the effort he makes to find his ideal life. His dreams couldn’t be very elaborate, of course, they were on his own scale, but in his own way he was looking for happiness. And in this film I tried to tell a story that’s funny, sad and tragic, the story of a peasant like him, Khmyr, for whom nothing goes right. His life is a struggle, just as his grandfather’s and great-grandfather’s had been, just as his father’s had been. And, totally unexpected to him, at the end of the film he finds that there are others who care about him, friends, neighbours, the government too. And in a collective farm he comes close to happiness. That’s the story of the film. Throughout my life the film train has been a wealth of ideas and themes. It made me love themes linked to the people, it made me love the life of the people, their dreams, hopes, joys and pain.”

As he says above, Medvedkin fascination lies with the people of his country. Instead of making his film into a moral tale about the truth about happiness, he is content is depicting the struggles, aspirations and triumphs of a common man – a simple man whom he has seen throughout his life in the Cine Train. That is why, I believe, it is not fair to call Happiness as a politically charged film even though it provides a good indication of the politics of Russia at that time. His Khmyr is not an icon of satire or propaganda, but of the Russian peasant himself. Khmyr is like Chaplin’s Tramp, not fitting easily into preformatted social structures, only that Khmyr is not the happy-go-lucky type like his American twin. Medvedkin seems to be of the opinion that, however strong and simple a system is, there will always be anomalies who will take time to settle down. This idea is reinforced by his other films The Story of Tit (1933) and Stop Thief! (1931), where too we have lazy or incompetent peasants trying to malinger and wriggle their way out of duties at the Kolkhoz.

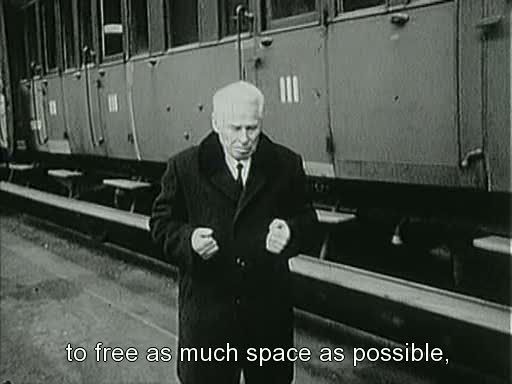

In Chris Marker’s brilliant film The Train Rolls On (1971), he recounts the rise and fall of the Cine Train, employing meditative voiceovers, stock photographs and interviews of Medvedkin himself. The Train Rolls On starts (and ends) with the image of a moving train, denoting at once the beginning of this film, the beginning of cinema and the beginning of revolutionary cinema heralded by the Cine Train. Marker, not without a tinge of sadness, documents the activities of the Train, from its inception to its death, and attempts to bring to light how revolutionary the vision of the group was. In the interviews, Medvedkin recalls the experience of traveling in the train, stopping at villages, carrying out the mission’s objective and working against all odds to give to people what he had taken from them. Marker’s work is a documentation of a (lost) documentation of history, of revolution and of change. Marker tells us that although most of the Cine Train’s work has gone into oblivion, the spirit of the undertaking has lived on. As he puts it: “The biggest mistake one could make would be to believe that [the Train] had come to a halt”.

In Chris Marker’s brilliant film The Train Rolls On (1971), he recounts the rise and fall of the Cine Train, employing meditative voiceovers, stock photographs and interviews of Medvedkin himself. The Train Rolls On starts (and ends) with the image of a moving train, denoting at once the beginning of this film, the beginning of cinema and the beginning of revolutionary cinema heralded by the Cine Train. Marker, not without a tinge of sadness, documents the activities of the Train, from its inception to its death, and attempts to bring to light how revolutionary the vision of the group was. In the interviews, Medvedkin recalls the experience of traveling in the train, stopping at villages, carrying out the mission’s objective and working against all odds to give to people what he had taken from them. Marker’s work is a documentation of a (lost) documentation of history, of revolution and of change. Marker tells us that although most of the Cine Train’s work has gone into oblivion, the spirit of the undertaking has lived on. As he puts it: “The biggest mistake one could make would be to believe that [the Train] had come to a halt”.

What is perhaps most unique about the Cine Train is its conviction that cinema is a medium that is of the people, for the people and by the people. That it can indeed bring a change in the lives of common people. That it is the only art which can create a revolution for good. This view is remarkably similar to Medvedkin’s contemporary and fellow Russian Dziga Vertov’s Kino Pravda theory. Nikolaï Izvolov, who headed the restoration of Happiness, narrates the strange phenomenon that Medvedkin and Vertov shared. Even though both lived in Moscow and were even next door neighbours for some time, they seem to have never met each other officially. And just before they had an opportunity to work together in the 50s, Vertov passed away. One only wonders what course cinema would have taken if they had joined hands. Herzog’s belief that cinema is the art form of the illiterates seems so true when watching the films of these pioneers. Somehow, it feels like cinema has moved backwards from where it started. One should at least be glad that their followers – the Dziga Vertov Group (Godard et al) and the Alexandr Medvedkin Group (Marker et al) – have tried to sustain the vision of their mentors, if not achieving the desired results.

In Happiness, Medvedkin sets up a hilarious contrast between Khmyr and his wife Anna by reversing the conventional notions of masculine and feminine. As Khmyr goes out in search of “happiness”, Anna grabs him by the collar and kisses him goodbye. She defends him against Foka’s exploitation. She steals a horse from thieves and rescues Khmyr from execution. She drives a tractor and runs the house. Heck, she even carries the horse down from the top of their hut! Medvedkin almost always frames her above the feeble Khmyr producing an amusing effect. Sergei Eisenstein called Medvedkin a “Bolshevik Chaplin”. Although I’m sure many will be surprised by that statement since the slapstick in Happiness seems to have aged a bit (but only as much as many of its American counterparts), there is much dark humour in Happiness to make up for that. I haven’t seen any Russian comedy of this period, except Pudovkin’s magnificent Chess Fever (1925), so I am not sure how this film stands out as a comedy among its contemporaries. But where the success of Happiness (and Medvedkin’s work in general) really lies, in hindsight, is in the fact that it offers us an alternate prism to view a country’s cinema, which has been reduced by text books to mere political messages and then a few cutting techniques.- theseventhart.info/

In Happiness, Medvedkin sets up a hilarious contrast between Khmyr and his wife Anna by reversing the conventional notions of masculine and feminine. As Khmyr goes out in search of “happiness”, Anna grabs him by the collar and kisses him goodbye. She defends him against Foka’s exploitation. She steals a horse from thieves and rescues Khmyr from execution. She drives a tractor and runs the house. Heck, she even carries the horse down from the top of their hut! Medvedkin almost always frames her above the feeble Khmyr producing an amusing effect. Sergei Eisenstein called Medvedkin a “Bolshevik Chaplin”. Although I’m sure many will be surprised by that statement since the slapstick in Happiness seems to have aged a bit (but only as much as many of its American counterparts), there is much dark humour in Happiness to make up for that. I haven’t seen any Russian comedy of this period, except Pudovkin’s magnificent Chess Fever (1925), so I am not sure how this film stands out as a comedy among its contemporaries. But where the success of Happiness (and Medvedkin’s work in general) really lies, in hindsight, is in the fact that it offers us an alternate prism to view a country’s cinema, which has been reduced by text books to mere political messages and then a few cutting techniques.- theseventhart.info/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar