Automatski Kafka je android i superjunak ali najusamljenije je biće na planetu.

Ultimativna postmodernistička dekonstrukcija stripova o superjunacima.

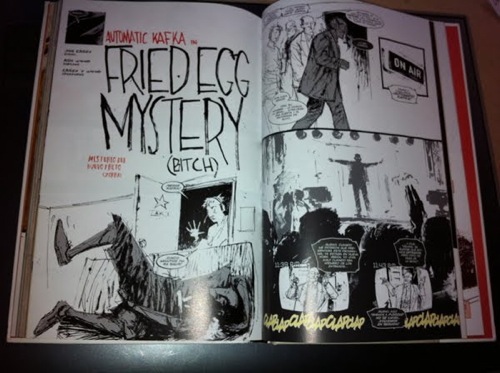

Automatic Kafka by Joe Casey (writer), Ashley Wood (artist), and Richard Starkings/Comicraft (letterer).

DC/Wildstorm, 9 issues (#1-9), cover dated September 2002 – July 2003.

Automatic Kafka never stood a chance. It was unlike almost anything that had come along before, and I’m amazed it lasted nine issues. On first glance, it looks too weird to read – Wood’s art is probably an acquired taste for most people, and there’s a lot of cursing, sex, violence, and gratuitous nudity in this book.  Many people may have picked up the first issue, read it, said WTF?, and dropped it. I almost did after a few issues, but I stuck with it, and I’m glad I did. This is a complex book that rewards multiple readings. It grows on you, and like most great modern comics, reads better in one sitting than spaced out over months.

Many people may have picked up the first issue, read it, said WTF?, and dropped it. I almost did after a few issues, but I stuck with it, and I’m glad I did. This is a complex book that rewards multiple readings. It grows on you, and like most great modern comics, reads better in one sitting than spaced out over months.

Many people may have picked up the first issue, read it, said WTF?, and dropped it. I almost did after a few issues, but I stuck with it, and I’m glad I did. This is a complex book that rewards multiple readings. It grows on you, and like most great modern comics, reads better in one sitting than spaced out over months.

Many people may have picked up the first issue, read it, said WTF?, and dropped it. I almost did after a few issues, but I stuck with it, and I’m glad I did. This is a complex book that rewards multiple readings. It grows on you, and like most great modern comics, reads better in one sitting than spaced out over months.

On the surface, AK is pretty straightforward. It’s a superhero comic about a washed-up superhero, Mr. Automatic Kafka himself. He’s an android and one of the strongest sentient beings on the planet, but he’s lonely. He tries drugs, he tries sex, he finally tries fame and gets hooked. Through the course of the run we meet his ex-teammates from the group The $tranger$ (with the dollar signs – Casey can be subtle, but not here) and how they’re faring, and there’s an interesting super-villain and a “traitor” to the cause, but that’s all window dressing. If you want to read this as a coarse superhero title, go ahead. It won’t disappoint, even though there’s not a lot of fights and explosions. There’s enough action to keep you interested. That’s not what Casey and Wood are about, however.

You can also read it as a parody of superhero comics, but I think Casey and Wood love superheroes too much to do that.  Sure, they’re parodying aspects of the genre, but you can see their respect for the institutions as well, so the parody is gentle, despite the sex and violence. What this comic really is is the ultimate deconstruction and homage to the superhero, and, I would argue, the truest postmodern superhero comic out there (okay, I haven’t read them all, but I would be surprised if there were a better one). Yes, Moore deconstructed the superhero 25 years ago, and Morrison did 15 years ago [Edit: we can adjust these dates a few years now, of course], and others have done it too, but Casey and Wood take it further than those guys did, giving us a superhero who is actively deconstructing himself, as well as characters who are all, one some level, aware that they are fictional constructs. It’s fascinating to see how Casey and Wood navigate these tricky waters without becoming too pretentious, a trap they usually avoid.

Sure, they’re parodying aspects of the genre, but you can see their respect for the institutions as well, so the parody is gentle, despite the sex and violence. What this comic really is is the ultimate deconstruction and homage to the superhero, and, I would argue, the truest postmodern superhero comic out there (okay, I haven’t read them all, but I would be surprised if there were a better one). Yes, Moore deconstructed the superhero 25 years ago, and Morrison did 15 years ago [Edit: we can adjust these dates a few years now, of course], and others have done it too, but Casey and Wood take it further than those guys did, giving us a superhero who is actively deconstructing himself, as well as characters who are all, one some level, aware that they are fictional constructs. It’s fascinating to see how Casey and Wood navigate these tricky waters without becoming too pretentious, a trap they usually avoid.

Sure, they’re parodying aspects of the genre, but you can see their respect for the institutions as well, so the parody is gentle, despite the sex and violence. What this comic really is is the ultimate deconstruction and homage to the superhero, and, I would argue, the truest postmodern superhero comic out there (okay, I haven’t read them all, but I would be surprised if there were a better one). Yes, Moore deconstructed the superhero 25 years ago, and Morrison did 15 years ago [Edit: we can adjust these dates a few years now, of course], and others have done it too, but Casey and Wood take it further than those guys did, giving us a superhero who is actively deconstructing himself, as well as characters who are all, one some level, aware that they are fictional constructs. It’s fascinating to see how Casey and Wood navigate these tricky waters without becoming too pretentious, a trap they usually avoid.

Sure, they’re parodying aspects of the genre, but you can see their respect for the institutions as well, so the parody is gentle, despite the sex and violence. What this comic really is is the ultimate deconstruction and homage to the superhero, and, I would argue, the truest postmodern superhero comic out there (okay, I haven’t read them all, but I would be surprised if there were a better one). Yes, Moore deconstructed the superhero 25 years ago, and Morrison did 15 years ago [Edit: we can adjust these dates a few years now, of course], and others have done it too, but Casey and Wood take it further than those guys did, giving us a superhero who is actively deconstructing himself, as well as characters who are all, one some level, aware that they are fictional constructs. It’s fascinating to see how Casey and Wood navigate these tricky waters without becoming too pretentious, a trap they usually avoid.

Casey and Wood dive right into things in the first issue, in which a depressed Kafka tries a new drug that is supposed to work on androids, since nothing else does. When he injects it, we immediately get one of the themes of the book – Kafka’s yearning to be human (yes, he’s just like Pinocchio!). He wants to have real sex with a woman, and he wants to enjoy sports, and he wants to laugh at sitcoms. Morrison did this with Cliff in Doom Patrol, so it’s not necessarily new, but it is still interesting to see the journey Kafka goes on to resolve his issues. And then Death shows up, totally naked. Of course, she’s a hot babe. It turns out Kafka’s pusher was a member of the Chemical Mob, an old group of villains from Kafka’s hero days, and he gave him some messed-up drugs.  This allows Kafka and Death to take a trip through Kafka’s subconscious, introducing us to the series. It’s a nice device. It also allows the creators to begin inserting themselves into the book (something they do in issue #9) and making postmodern comments. Death mentions that Kafka’s life in the 1980s was “like something out of a Michelinie comic.” Everyone talks like this – it’s artificial, but suits the book perfectly. They also stop in and check out Wood’s drawing table, on which is the actual page we’re reading. The first issue ends with a text piece by the creators (Casey, most likely), which alternately tells us that AK is the most subversive and brilliant piece of writing ever and also that it’s crap. This has become Casey’s thing in recent years, and it’s not as annoying as it might sound. He wants us to interact with the comic itself, get involved, look for clues that may or may not be there, but most of all, think about it. Use our brains. Kafka is us, ultimately, looking for meaning and finding only corny speeches, stale supervillains, sex selling product, and fickle creators and a reading public that determines our fate.

This allows Kafka and Death to take a trip through Kafka’s subconscious, introducing us to the series. It’s a nice device. It also allows the creators to begin inserting themselves into the book (something they do in issue #9) and making postmodern comments. Death mentions that Kafka’s life in the 1980s was “like something out of a Michelinie comic.” Everyone talks like this – it’s artificial, but suits the book perfectly. They also stop in and check out Wood’s drawing table, on which is the actual page we’re reading. The first issue ends with a text piece by the creators (Casey, most likely), which alternately tells us that AK is the most subversive and brilliant piece of writing ever and also that it’s crap. This has become Casey’s thing in recent years, and it’s not as annoying as it might sound. He wants us to interact with the comic itself, get involved, look for clues that may or may not be there, but most of all, think about it. Use our brains. Kafka is us, ultimately, looking for meaning and finding only corny speeches, stale supervillains, sex selling product, and fickle creators and a reading public that determines our fate.

This allows Kafka and Death to take a trip through Kafka’s subconscious, introducing us to the series. It’s a nice device. It also allows the creators to begin inserting themselves into the book (something they do in issue #9) and making postmodern comments. Death mentions that Kafka’s life in the 1980s was “like something out of a Michelinie comic.” Everyone talks like this – it’s artificial, but suits the book perfectly. They also stop in and check out Wood’s drawing table, on which is the actual page we’re reading. The first issue ends with a text piece by the creators (Casey, most likely), which alternately tells us that AK is the most subversive and brilliant piece of writing ever and also that it’s crap. This has become Casey’s thing in recent years, and it’s not as annoying as it might sound. He wants us to interact with the comic itself, get involved, look for clues that may or may not be there, but most of all, think about it. Use our brains. Kafka is us, ultimately, looking for meaning and finding only corny speeches, stale supervillains, sex selling product, and fickle creators and a reading public that determines our fate.

This allows Kafka and Death to take a trip through Kafka’s subconscious, introducing us to the series. It’s a nice device. It also allows the creators to begin inserting themselves into the book (something they do in issue #9) and making postmodern comments. Death mentions that Kafka’s life in the 1980s was “like something out of a Michelinie comic.” Everyone talks like this – it’s artificial, but suits the book perfectly. They also stop in and check out Wood’s drawing table, on which is the actual page we’re reading. The first issue ends with a text piece by the creators (Casey, most likely), which alternately tells us that AK is the most subversive and brilliant piece of writing ever and also that it’s crap. This has become Casey’s thing in recent years, and it’s not as annoying as it might sound. He wants us to interact with the comic itself, get involved, look for clues that may or may not be there, but most of all, think about it. Use our brains. Kafka is us, ultimately, looking for meaning and finding only corny speeches, stale supervillains, sex selling product, and fickle creators and a reading public that determines our fate.

Each issue addresses an aspect of what Casey is trying to do with the book. He brings in the National Park Service, which is a government agency in the Wildstorm Universe, but I’m not sure if Casey himself invented it (he digs it, though). The NPS wants Kafka to work for them, since the government built him in the first place. Instead, he becomes a celebrity to “hide in plain sight.” This allows Casey to get to the meat of the book, which is a critique of mass consumerism and America’s obsession with patriotism and sex.  If you don’t think those two go together, Casey makes it clear that they do. Kafka becomes a corporate shill and a game show host (of “The Million Dollar Detail,” which sounds ridiculous until you remember that shows like “Fear Factor” are actually on the air [Well, they were in 2005]), and this brings him back into the public eye and makes him an advertising dream. Casey also brings in his old teammates The Constitution of the United States and Helen of Troy. The Constitution (and his scantily-clad and oversexed sidekick, The Declaration of Independence) is again not the model of subtlety, as he is now a government soldier working covert ops in dirty, out-of-the-way places (like the Comedian in Watchmen, I suppose), but again, it allows Casey to point out the stereotypes of superhero comics while still indulging in them. When, in issue #5, The Constitution sees his sidekick blown apart by “the bad guys,” he says, “This is what it’s all about. The slow march to the final showdown, the inevitable violence that ensues … gratuitous fight scenes …” This is what the public wants, and this is what The Constitution has been programmed to love. He does enjoy it, but recognizes its cost. We recognize that we have been programmed to enjoy this, and although we also recognize the kookiness, we can’t get past it. We’re part of the problem as much as The Constitution is. After destroying the bad guys, The Constitution returns stateside, where he enters the porn industry. Again, it’s not terribly subtle, but it does make a point that others have made, most notably Eric Schlosser in Reefer Madness – there’s almost nothing as all-American as porn, even though people don’t want to admit it. The Constitution links the two when he says, “Vixen Video. The gold standard of the porn industry. Very American. My kind of place.” On his belly is a tattoo that says “Old Glory” and an arrow pointing down. He’s a true American hero, in every sense of the word. By the last issue, he’s trying to set a record for quantity of girls serviced on tape. It’s all very beautiful.

If you don’t think those two go together, Casey makes it clear that they do. Kafka becomes a corporate shill and a game show host (of “The Million Dollar Detail,” which sounds ridiculous until you remember that shows like “Fear Factor” are actually on the air [Well, they were in 2005]), and this brings him back into the public eye and makes him an advertising dream. Casey also brings in his old teammates The Constitution of the United States and Helen of Troy. The Constitution (and his scantily-clad and oversexed sidekick, The Declaration of Independence) is again not the model of subtlety, as he is now a government soldier working covert ops in dirty, out-of-the-way places (like the Comedian in Watchmen, I suppose), but again, it allows Casey to point out the stereotypes of superhero comics while still indulging in them. When, in issue #5, The Constitution sees his sidekick blown apart by “the bad guys,” he says, “This is what it’s all about. The slow march to the final showdown, the inevitable violence that ensues … gratuitous fight scenes …” This is what the public wants, and this is what The Constitution has been programmed to love. He does enjoy it, but recognizes its cost. We recognize that we have been programmed to enjoy this, and although we also recognize the kookiness, we can’t get past it. We’re part of the problem as much as The Constitution is. After destroying the bad guys, The Constitution returns stateside, where he enters the porn industry. Again, it’s not terribly subtle, but it does make a point that others have made, most notably Eric Schlosser in Reefer Madness – there’s almost nothing as all-American as porn, even though people don’t want to admit it. The Constitution links the two when he says, “Vixen Video. The gold standard of the porn industry. Very American. My kind of place.” On his belly is a tattoo that says “Old Glory” and an arrow pointing down. He’s a true American hero, in every sense of the word. By the last issue, he’s trying to set a record for quantity of girls serviced on tape. It’s all very beautiful.

If you don’t think those two go together, Casey makes it clear that they do. Kafka becomes a corporate shill and a game show host (of “The Million Dollar Detail,” which sounds ridiculous until you remember that shows like “Fear Factor” are actually on the air [Well, they were in 2005]), and this brings him back into the public eye and makes him an advertising dream. Casey also brings in his old teammates The Constitution of the United States and Helen of Troy. The Constitution (and his scantily-clad and oversexed sidekick, The Declaration of Independence) is again not the model of subtlety, as he is now a government soldier working covert ops in dirty, out-of-the-way places (like the Comedian in Watchmen, I suppose), but again, it allows Casey to point out the stereotypes of superhero comics while still indulging in them. When, in issue #5, The Constitution sees his sidekick blown apart by “the bad guys,” he says, “This is what it’s all about. The slow march to the final showdown, the inevitable violence that ensues … gratuitous fight scenes …” This is what the public wants, and this is what The Constitution has been programmed to love. He does enjoy it, but recognizes its cost. We recognize that we have been programmed to enjoy this, and although we also recognize the kookiness, we can’t get past it. We’re part of the problem as much as The Constitution is. After destroying the bad guys, The Constitution returns stateside, where he enters the porn industry. Again, it’s not terribly subtle, but it does make a point that others have made, most notably Eric Schlosser in Reefer Madness – there’s almost nothing as all-American as porn, even though people don’t want to admit it. The Constitution links the two when he says, “Vixen Video. The gold standard of the porn industry. Very American. My kind of place.” On his belly is a tattoo that says “Old Glory” and an arrow pointing down. He’s a true American hero, in every sense of the word. By the last issue, he’s trying to set a record for quantity of girls serviced on tape. It’s all very beautiful.

If you don’t think those two go together, Casey makes it clear that they do. Kafka becomes a corporate shill and a game show host (of “The Million Dollar Detail,” which sounds ridiculous until you remember that shows like “Fear Factor” are actually on the air [Well, they were in 2005]), and this brings him back into the public eye and makes him an advertising dream. Casey also brings in his old teammates The Constitution of the United States and Helen of Troy. The Constitution (and his scantily-clad and oversexed sidekick, The Declaration of Independence) is again not the model of subtlety, as he is now a government soldier working covert ops in dirty, out-of-the-way places (like the Comedian in Watchmen, I suppose), but again, it allows Casey to point out the stereotypes of superhero comics while still indulging in them. When, in issue #5, The Constitution sees his sidekick blown apart by “the bad guys,” he says, “This is what it’s all about. The slow march to the final showdown, the inevitable violence that ensues … gratuitous fight scenes …” This is what the public wants, and this is what The Constitution has been programmed to love. He does enjoy it, but recognizes its cost. We recognize that we have been programmed to enjoy this, and although we also recognize the kookiness, we can’t get past it. We’re part of the problem as much as The Constitution is. After destroying the bad guys, The Constitution returns stateside, where he enters the porn industry. Again, it’s not terribly subtle, but it does make a point that others have made, most notably Eric Schlosser in Reefer Madness – there’s almost nothing as all-American as porn, even though people don’t want to admit it. The Constitution links the two when he says, “Vixen Video. The gold standard of the porn industry. Very American. My kind of place.” On his belly is a tattoo that says “Old Glory” and an arrow pointing down. He’s a true American hero, in every sense of the word. By the last issue, he’s trying to set a record for quantity of girls serviced on tape. It’s all very beautiful. Kafka doesn’t get the short shrift, either, as Casey continues to make his point about celebrity culture alongside his point about American consumers. He hooks up with his old teammate Helen of Troy, and they have wild and crazy sex (in issue #6) which reveals to Kafka that Helen is actually an old woman using sex-magic to keep herself looking young. If that’s not a comment on America’s obsession with youth, I don’t know what is. Casey also brings in his own ideas, one he’s talked about in columns for CBR – Fuck Fame. That’s when someone is so famous you simply want to have sex with them, whether or not they’re particularly attractive. These superheroes have it. The agent from the NPS who first interviews Kafka (in issue #3) crawls, panting, over the desk toward him because she used to have a huge crush on him. The receptionist at Vixen Video fellates The Constitution (in issue #7) because she used to have posters of him on the wall. These are superheroes who are celebrities, after all, and Casey knows that they would use that celebrity to get what they want, even after their time has passed.

Kafka doesn’t get the short shrift, either, as Casey continues to make his point about celebrity culture alongside his point about American consumers. He hooks up with his old teammate Helen of Troy, and they have wild and crazy sex (in issue #6) which reveals to Kafka that Helen is actually an old woman using sex-magic to keep herself looking young. If that’s not a comment on America’s obsession with youth, I don’t know what is. Casey also brings in his own ideas, one he’s talked about in columns for CBR – Fuck Fame. That’s when someone is so famous you simply want to have sex with them, whether or not they’re particularly attractive. These superheroes have it. The agent from the NPS who first interviews Kafka (in issue #3) crawls, panting, over the desk toward him because she used to have a huge crush on him. The receptionist at Vixen Video fellates The Constitution (in issue #7) because she used to have posters of him on the wall. These are superheroes who are celebrities, after all, and Casey knows that they would use that celebrity to get what they want, even after their time has passed.

It all comes apart in the end, of course. A former supervillain, Galaxia, who replaced his head with a small galaxy, comes to The Warning’s house for help. The Warning, who put the team together back in the 1980s and is the smartest guy around, brokers a reconciliation between Galaxia and Kafka and then recycles Galaxia as an energy source, since he’s working on things for the government and could use the energy of a galaxy. The reconciliation scene between Galaxia and Kafka is nicely done, showing again that superheroes, when they’re done like the Big Two do them, become mere stereotypes and ultimately dull. Galaxia is dying, and that gives him perspective on what he was doing fifteen years earlier.  Unlike, say, Doctor Doom, Galaxia regrets the things he did in the name of science, and understands that he didn’t always make the correct choice. Kafka, for his part, is able to grant a dying man his request for a truce. Then, of course, The Warning imprisons Galaxia to use for energy, and all our good feelings are washed away. When Kafka finds out, he confronts The Warning, but is ineffectual against him. The Warning sums up Kafka’s problem: “You’re searching for that thing you thought you were missing out on as an artificial construct … You’d watch humanity teeming around and you’d feel empty inside. … Humanity is confusion. Welcome to it.” This sends Kafka on his last adventure, as a butterfly appears and tells him, “I’ve been sent here to rescue you from the possible tedium of another so-called ‘story arc’ in the relentless continuum you call ‘life.’ ” This leads to issue #9, in which Casey and Wood appear.

Unlike, say, Doctor Doom, Galaxia regrets the things he did in the name of science, and understands that he didn’t always make the correct choice. Kafka, for his part, is able to grant a dying man his request for a truce. Then, of course, The Warning imprisons Galaxia to use for energy, and all our good feelings are washed away. When Kafka finds out, he confronts The Warning, but is ineffectual against him. The Warning sums up Kafka’s problem: “You’re searching for that thing you thought you were missing out on as an artificial construct … You’d watch humanity teeming around and you’d feel empty inside. … Humanity is confusion. Welcome to it.” This sends Kafka on his last adventure, as a butterfly appears and tells him, “I’ve been sent here to rescue you from the possible tedium of another so-called ‘story arc’ in the relentless continuum you call ‘life.’ ” This leads to issue #9, in which Casey and Wood appear.

Unlike, say, Doctor Doom, Galaxia regrets the things he did in the name of science, and understands that he didn’t always make the correct choice. Kafka, for his part, is able to grant a dying man his request for a truce. Then, of course, The Warning imprisons Galaxia to use for energy, and all our good feelings are washed away. When Kafka finds out, he confronts The Warning, but is ineffectual against him. The Warning sums up Kafka’s problem: “You’re searching for that thing you thought you were missing out on as an artificial construct … You’d watch humanity teeming around and you’d feel empty inside. … Humanity is confusion. Welcome to it.” This sends Kafka on his last adventure, as a butterfly appears and tells him, “I’ve been sent here to rescue you from the possible tedium of another so-called ‘story arc’ in the relentless continuum you call ‘life.’ ” This leads to issue #9, in which Casey and Wood appear.

Unlike, say, Doctor Doom, Galaxia regrets the things he did in the name of science, and understands that he didn’t always make the correct choice. Kafka, for his part, is able to grant a dying man his request for a truce. Then, of course, The Warning imprisons Galaxia to use for energy, and all our good feelings are washed away. When Kafka finds out, he confronts The Warning, but is ineffectual against him. The Warning sums up Kafka’s problem: “You’re searching for that thing you thought you were missing out on as an artificial construct … You’d watch humanity teeming around and you’d feel empty inside. … Humanity is confusion. Welcome to it.” This sends Kafka on his last adventure, as a butterfly appears and tells him, “I’ve been sent here to rescue you from the possible tedium of another so-called ‘story arc’ in the relentless continuum you call ‘life.’ ” This leads to issue #9, in which Casey and Wood appear.

Casey and Wood admit what they’re doing in issue #9 isn’t original. They name-check Julius Schwartz and Curt Swan and Wolfman/Perez and Morrison and admit they’re ripping them off. That’s not the point. As they tell us, the point is that Kafka is their creation, and they labored over him, and they don’t want to share him. It’s an admirable sentiment. Kafka still doesn’t quite get the fact that he’s a comic book creation rather than an actual superhero, but that’s okay, because it’s all artificial anyway. Casey makes the point that AK was an experiment, and experiments don’t always go the way the creators want them to. He and Wood occasionally play the victim – Wood says at one point that there’s lines you can’t cross, perhaps ignoring that maybe the book’s not that good (I’m not making that argument, as you can see, but for someone to blame the audience for not buying something because it’s too “edgy” is a little silly) – but basically they are trying to point out that, unfortunately, the comic book industry has become a bit too homogenized, especially the Big Two (Wildstorm is owned by DC, after all).  Casey tells Kafka he’s not commercial enough, and Kafka sputters, ” ‘Not commercial …’? But … we’re superheroes …!” Well, sure you are, Kafka, but not the kind that people like. At the end of the book, Wood “decreates” Kafka, so that he doesn’t become a commodity. Kafka says it feels better than the drugs ever did, and Casey tells him “That’s because this oblivion is for real. And the real thing is always better.” It’s a nice ending to the series and the experiment.

Casey tells Kafka he’s not commercial enough, and Kafka sputters, ” ‘Not commercial …’? But … we’re superheroes …!” Well, sure you are, Kafka, but not the kind that people like. At the end of the book, Wood “decreates” Kafka, so that he doesn’t become a commodity. Kafka says it feels better than the drugs ever did, and Casey tells him “That’s because this oblivion is for real. And the real thing is always better.” It’s a nice ending to the series and the experiment.

Casey tells Kafka he’s not commercial enough, and Kafka sputters, ” ‘Not commercial …’? But … we’re superheroes …!” Well, sure you are, Kafka, but not the kind that people like. At the end of the book, Wood “decreates” Kafka, so that he doesn’t become a commodity. Kafka says it feels better than the drugs ever did, and Casey tells him “That’s because this oblivion is for real. And the real thing is always better.” It’s a nice ending to the series and the experiment.

Casey tells Kafka he’s not commercial enough, and Kafka sputters, ” ‘Not commercial …’? But … we’re superheroes …!” Well, sure you are, Kafka, but not the kind that people like. At the end of the book, Wood “decreates” Kafka, so that he doesn’t become a commodity. Kafka says it feels better than the drugs ever did, and Casey tells him “That’s because this oblivion is for real. And the real thing is always better.” It’s a nice ending to the series and the experiment.

I’m not sure why Automatic Kafka failed, despite the way I started this post (that was more for dramatics!). I don’t know enough about the industry to guess about the promotional stuff DC did for it. I do know that it is possible for a book like AK to succeed. Maybe it was too outre for the mainstream superhero crowd, but too corporate for the indy crowd. I don’t know. I do know that if you like simple morality tales from your superheroes, this book is not for you. It challenges you to think about heroes differently, but also about the country and what it stands for, our relationship to our self-created celebrities, and our own purchasing power in an increasingly consumer-and-manufacturer-dominated world. Casey asks you to think about yourself, and perhaps we won’t like the answers.

In yet another great tragedy of our modern age, Automatic Kafka has not been collected in a handsome, giant-sized omnibus edition with commentary by the creators. Damn you, DC and Wildstorm! Get on it! I have no idea if the issues are difficult to find, but they’re definitely worth the hunt!

[It has been pointed out that I pretty much ignore issue #4, the rather infamous one that focuses on the "Peanuts" gang, all grown up. It's a brilliant issue, actually, and contains some of the themes that Casey delves into during the rest of the run, but it's also largely self-contained, so I kind of passed it by. I do apologize. If I wrote this today, I'd probably write more about it. But I should point out that it's a damned good story.] - Greg Burgas

Critical Essay: The Case for Automatic Kafka

Authored by Dan Coyle

Automatic Kafka #1-7

Automatic Kafka #1-7

Writer: Joe Casey

Artist: Ashley Wood

Publisher: WildStorm

Automatic Kafka Created by Casey and Wood.

Authored by Dan Coyle

Automatic Kafka #1-7

Automatic Kafka #1-7Writer: Joe Casey

Artist: Ashley Wood

Publisher: WildStorm

Automatic Kafka Created by Casey and Wood.

Celebrity is an American institution: from dim construction workers to great actors to anorexic harpies who hate Bill Clinton, if you can get on camera, if you can get people to pay attention to you, you’re on top of the world. But one of the ironies of fame is that one can work so hard and so long to achieve it and lose it fairly quickly. Or, one can be in the spotlight for a decade and then slowly fade away, reduced to a trivia question.

What happens when that "trivia question" turns out to be a superhero? And what happens when he decides it’s time for a comeback?Automatic Kafka debuted last July to little fanfare, and like the majority of the Eye of the Storm "suggested for mature readers " line, has stayed under the radar. It’s a shame, however, since Joe Casey and Ashley Wood’s series, while initially rather confounding, has become one of the most interesting titles on the market.As the cover of every issue states, Automatic Kafka is "A Superhero Comicbook ". That description can be taken as a post-meta-whatever ironic statement or what have you, but it’s also a very apt, honest description: Automatic Kafka, the title character, is a superhero. Automatic Kafka was a member of the $trangers$, the WildStorm U’s premiere 1980s super team. In the decade since the group disbanded in 1990, he’s become a strung out junkie, shooting up Nanotech in the slums of Mexico City. In issue #1, he overdoses and nearly dies... and the experience leads him on a journey of self-discovery.

Well, not quite. One of the best qualities of Automatic Kafka is the sense that you never knows where the story is going to go next: in issues #2 and #3, the government, in the form of the National Park Service (shades of The Invisible Man) goes looking for A.K. in an attempt to recruit him. Instead of slaving for the Man, Automatic Kafka, inspired by his old $tranger$ boss The Warning, decides to step back in the limelight- make sure the world notices him again. And so A.K.’s little adventure has gone for the past few issues, as he hosts The Million Dollar Detail, America’s #1 game show, makes a porn film with his old teammate Helen of Troy, and finds himself inexorably drawn into the orbit of all the old heroes and villains he used to know. Issue #4 is the one exception: it’s a bizarre, oddly amusing one-issue experiment that follows a dejectedMillion Dollar Detail contestant named Charles Brown, his therapist, Lucy, and his sister, Sally...

While Casey has a tendency to wear his influences on his sleeve- comparisons to Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol have been made more than once- it would be too simple to dismiss Automatic Kafka as another deconstructionist "post-superhero " comic book. Casey has zeroed in on an idea that’s rarely been explored fully in the realm of "mature " superheroes. While Rob Liefeld tried- and failed, naturally- to do it in Youngblood- Casey gets it: in the "real world ", superheroes would be big celebrities, standing should to shoulder with the highest rated cable news pundit or $20 million dollar action star. But all stars burn out eventually, and in a "real world " scenario, wouldn’t superheroes? In comics, however, time is cheated year after year. While The $strangers$ can be taken as an analogue for the Doom Patrol- after all, our protagonist is a robot- but even more obviously, they’re analogue for the Avengers. Helen of Tory is the Scarlet Witch with Tantric Sex powers, The Constitution of the United States a Reagan- style Captain America puppet. And Since A.K. has always had a crush on Helen, I don’t need to tell you whom he represents. But like the Doom Patrol, the Avengers get reinvented every couple of years- hell, all corporate superhero properties do. While yes, there’s always a chance these characters will be rediscovered by a new generation of fans, the status quo must always be the status go- there’s no real time for the lights to go out, for the heroes to leave the stage. The Authority was a book that was very much of its time, yet DC seems convinced that the defilibrators must be slapped on it, to bring it back to life.

While Casey has a tendency to wear his influences on his sleeve- comparisons to Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol have been made more than once- it would be too simple to dismiss Automatic Kafka as another deconstructionist "post-superhero " comic book. Casey has zeroed in on an idea that’s rarely been explored fully in the realm of "mature " superheroes. While Rob Liefeld tried- and failed, naturally- to do it in Youngblood- Casey gets it: in the "real world ", superheroes would be big celebrities, standing should to shoulder with the highest rated cable news pundit or $20 million dollar action star. But all stars burn out eventually, and in a "real world " scenario, wouldn’t superheroes? In comics, however, time is cheated year after year. While The $strangers$ can be taken as an analogue for the Doom Patrol- after all, our protagonist is a robot- but even more obviously, they’re analogue for the Avengers. Helen of Tory is the Scarlet Witch with Tantric Sex powers, The Constitution of the United States a Reagan- style Captain America puppet. And Since A.K. has always had a crush on Helen, I don’t need to tell you whom he represents. But like the Doom Patrol, the Avengers get reinvented every couple of years- hell, all corporate superhero properties do. While yes, there’s always a chance these characters will be rediscovered by a new generation of fans, the status quo must always be the status go- there’s no real time for the lights to go out, for the heroes to leave the stage. The Authority was a book that was very much of its time, yet DC seems convinced that the defilibrators must be slapped on it, to bring it back to life.No one slapped the defilibrators on Automatic Kafka and the rest of the $tranger$- they walked off the stage over a decade ago. But old habits die hard. Automatic Kafka may become a game show host and a porn star to get the Feds off his back- but more than that; he’s got to find a purpose in life other that shooting up. He’s the quintessential redemptive star who’s off the drugs and looking to recapture his old past- somewhere past The Surreal Life yet far away from the Miracle of Travolta. Automatic Kafka’s trying to find his place in the world, and every issue he finds himself in yet another strange place. Fame isn’t just a perk for A.K.- at this point in his existence; it’s a survival mechanism. And the absurdities of fame surround him at every tune. For him, the only way of holding on is selling out.

One of the book’s best assets- and, sadly, one of its biggest weaknesses- is the artwork of co-creator Ashley Wood. Wood’s work can resemble a berserk three-way between Dave McKean, Bill Sienkewicz, and Simon Bisley. The artist has previously worked on HellSpawn among other titles and currently does illustration work for the video game magazine Play. Wood’s work is often criticized for being hard to follow, and initial reviews of Automatic Kafka were full of fire about how the first issue was impossible to understand. In the early issues, Wood’s work was difficult to "get "- scene transitions were handled sloppily, particularly when Automatic Kafka is in his dream stare, it took a few once-overs to get what was going on. The satirical jokes in the Charles Brown issue take another reading to understand because Wood’s rendering of the characters doesn’t make it apparent enough what Casey is actually going for. Yet it’s difficult to imagine a more appropriate artist to draw the world of A.K. because so much of it is shot through with exaggeration and satire. There are some truly, truly beautiful bits in this book, and in the last three issues as that overall story arc has begun to form; Wood’s art has really cohered. Issue #5, the Constitution of the United States solo story, and the Helen of Troy story in issue #6 look wonderful.

It’s with issue #7 that one of the $tranger$’ old super villains, Galaxia, comes for a visit, but like the heroes, he’s just trying to figure out what to do with his life. It’s with this issue, released last week, that things have really gotten interesting, even if the next issue blurb reads "What Do You Care?! " Sales have not exactly been high, and the recent month long delay in issue is surely going to deliver another blow to the title’s chances of surviving its first year unless a trade paperback collects the first story arc. It’s kind of disheartening to see what looks to be a fairly standard plot beginning to emerge, even if there were plenty of clues leading up to it.

It’s with issue #7 that one of the $tranger$’ old super villains, Galaxia, comes for a visit, but like the heroes, he’s just trying to figure out what to do with his life. It’s with this issue, released last week, that things have really gotten interesting, even if the next issue blurb reads "What Do You Care?! " Sales have not exactly been high, and the recent month long delay in issue is surely going to deliver another blow to the title’s chances of surviving its first year unless a trade paperback collects the first story arc. It’s kind of disheartening to see what looks to be a fairly standard plot beginning to emerge, even if there were plenty of clues leading up to it.Casey, however, may still surprise the reader with what will happen. Automatic Kafka is his best work since Mr. Majestic, a strange, twisted satire that really deserves a chance to grow in this market. Casey had been saying for the past few years as a hype machine for himself, but more often than not his work either imploded on impact (The Uncanny X-Men ) or simply couldn’t follow a good concept with good execution (the dull bail bondsman for super villains title Codeflesh ). With Automatic Kafka, he seems to have nailed it, a wildly entertaining "superhero comicbook ", but Behind the Music in the 80s revival age. If you’ve ever wondered what happens after there are no villains to fight, when the fans stop cheering, when the 15 minutes are finally up for the modern superhero, well, Automatic Kafka’s wondering too. And it’s a kick reading how he tries to figure it out each month.

UP, UP AND AWAY… CASEY TALKS 'ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN' AND 'AUTOMATIC KAFKA'

The Cheese Stands Alone: Automatic Kafka #4

The Cheese Stands Alone is a semi-regular column featuring examinations of single issues that can be understood and appreciated on their own, without reading any of the preceding or following issues of the series.

Automatic Kafka was an incredible, short-lived series created by writer Joe Casey and artist Ashley Wood in 2002. Over the course of just nine issues, Casey and Wood delved into the problems of government corruption, the arbitrary and sometimes destructive nature of fame, the dangers of technology, and even a meta-discussion about the frustrations faced by the modern comicbook creator. All of this was explored through the eyes of the title character, a washed-up android superhero who just wanted to get as close as he could to something like humanity. It's an excellent series that is jam-packed with all manner of crazy, lewd, violent, and daring material, and I wholeheartedly recommend it. But forAutomatic Kafka #4, Casey and Wood briefly set aside all of the people and things they had been and would be developing, and devoted an entire issue to the characters from the beloved newspaper comicstrip Peanuts. All grown up now, Charlie Brown and company still have largely the same relationships with one another that they had as children. The difference is that as adults, those relationships have become several shades darker.

It's remarkable the care that both creators took in composing this issue. Everything and everyone you could want to see from Peanuts is there, but twisted and/or pushed to its logical extreme so that we get a much different version of these oh-so-familiar faces and ideas. There's Pig-Pen as a homeless man, Woodstock as a tiny yellow bird whom Snoopy kills as a gift for his master, The Great Pumpkin as a delusion so powerful Linus must spend his days in an insane asylum. Schroeder shows up to play a concert, now a successful musician, but no less detached or wry than ever. And remember Lucy's five-cent psychiatry stand? Well she's a practicing therapist now, and Charlie Brown is still her patient/mental torture victim. He's also her estranged husband, and their dysfunctional, depressing marriage is the central focus of Automatic Kafka #4. Or perhaps more accurately, the focus is on Charlie's personal dysfunction and depression.

The basic arc of the story is this: Charlie Brown returns home after losing as a contestant on a game show (hosted by Automatic Kafka himself in the preceding issue), and is forced to live another day in a life that he despises. After an abusive therapy session with his wife, Charlie and his sister visit her husband (Linus) in the asylum where he now lives, and the doctor there gives them a pretty hopeless assessment of his condition. Then Charlie goes to Schroeder's concert, where he drinks all alone and watches Lucy shamelessly throws herself at their old friend. Also at the event is the Little Red-Haired Girl, now shallow and self-important and working at a makeup counter, and Charlie gazes at her from afar as she hits on some random, sleazy schmuck. Eventually, Charlie's inebriation and jealousy get the best of him, and he breaks, screaming at the aforementioned schmuck about how not everyone is beautiful or popular or successful or happy. Finally, he is thrown out of the party (at Lucy's shrill demand), and he stumbles into Pig-Pen living on the street. Returning home, Charlie finds the dead bird offering Snoopy left him, and then sets to writing a somewhat desperate letter asking for a second chance to appear on the game show on which he was so recently defeated. Basically, life dumps all over him, and even though he sees how sad and hopeless things really are, he tries to keep his chin up and look for potential routes to happiness in his dismal world.

Of course, this is exactly who Charlie Brown has always been: a sad sack buried in depression but aiming for optimism. It's what made him so charming and relatable inPeanuts, and it has the same effect in Automatic Kafka #4. Honestly, even if you'd somehow never heard of Charles Schulz's comic strip, this issue would still be great. I admit that the first time I read it, the Peanuts connection went entirely over my head, but everything is so well-scripted and the themes so universal that I loved the story anyway. You don't need to know everything about everyone's histories to understand the fucked up nature of all of their relationships in the present. We've all felt jealousy, hopelessness, and lust. We all have friends we've lost touch with, and others we wish we could. Everybody, at one time or another, takes stock of their lives and feels something comparable to, "Good grief." It's whyPeanuts was and is so popular, and why it deserves this kind of thoughtful, brilliant homage. It's also why Automatic Kafka #4 can be read and adored without any prior Automatic Kafkaor Peanuts knowledge whatsoever.

Then again, understanding the numerous, specific details which Casey and Wood include can only serve to improve the experience. Every page, if not every panel, has a tribute to the source material, a twist on it, and a bit of heartbreak. Even the cover is an allusion to Snoopy battling the Red Baron from atop his doghouse. Automatic Kafka #4 is a poignant and respectful examination of what made Peanuts so great, as well as a mirror held up to the comicstrip's darkest aspects. - comicsmatter.blogspot.com/

Automatic Kafka was an incredible, short-lived series created by writer Joe Casey and artist Ashley Wood in 2002. Over the course of just nine issues, Casey and Wood delved into the problems of government corruption, the arbitrary and sometimes destructive nature of fame, the dangers of technology, and even a meta-discussion about the frustrations faced by the modern comicbook creator. All of this was explored through the eyes of the title character, a washed-up android superhero who just wanted to get as close as he could to something like humanity. It's an excellent series that is jam-packed with all manner of crazy, lewd, violent, and daring material, and I wholeheartedly recommend it. But forAutomatic Kafka #4, Casey and Wood briefly set aside all of the people and things they had been and would be developing, and devoted an entire issue to the characters from the beloved newspaper comicstrip Peanuts. All grown up now, Charlie Brown and company still have largely the same relationships with one another that they had as children. The difference is that as adults, those relationships have become several shades darker.

It's remarkable the care that both creators took in composing this issue. Everything and everyone you could want to see from Peanuts is there, but twisted and/or pushed to its logical extreme so that we get a much different version of these oh-so-familiar faces and ideas. There's Pig-Pen as a homeless man, Woodstock as a tiny yellow bird whom Snoopy kills as a gift for his master, The Great Pumpkin as a delusion so powerful Linus must spend his days in an insane asylum. Schroeder shows up to play a concert, now a successful musician, but no less detached or wry than ever. And remember Lucy's five-cent psychiatry stand? Well she's a practicing therapist now, and Charlie Brown is still her patient/mental torture victim. He's also her estranged husband, and their dysfunctional, depressing marriage is the central focus of Automatic Kafka #4. Or perhaps more accurately, the focus is on Charlie's personal dysfunction and depression.

The basic arc of the story is this: Charlie Brown returns home after losing as a contestant on a game show (hosted by Automatic Kafka himself in the preceding issue), and is forced to live another day in a life that he despises. After an abusive therapy session with his wife, Charlie and his sister visit her husband (Linus) in the asylum where he now lives, and the doctor there gives them a pretty hopeless assessment of his condition. Then Charlie goes to Schroeder's concert, where he drinks all alone and watches Lucy shamelessly throws herself at their old friend. Also at the event is the Little Red-Haired Girl, now shallow and self-important and working at a makeup counter, and Charlie gazes at her from afar as she hits on some random, sleazy schmuck. Eventually, Charlie's inebriation and jealousy get the best of him, and he breaks, screaming at the aforementioned schmuck about how not everyone is beautiful or popular or successful or happy. Finally, he is thrown out of the party (at Lucy's shrill demand), and he stumbles into Pig-Pen living on the street. Returning home, Charlie finds the dead bird offering Snoopy left him, and then sets to writing a somewhat desperate letter asking for a second chance to appear on the game show on which he was so recently defeated. Basically, life dumps all over him, and even though he sees how sad and hopeless things really are, he tries to keep his chin up and look for potential routes to happiness in his dismal world.

Of course, this is exactly who Charlie Brown has always been: a sad sack buried in depression but aiming for optimism. It's what made him so charming and relatable inPeanuts, and it has the same effect in Automatic Kafka #4. Honestly, even if you'd somehow never heard of Charles Schulz's comic strip, this issue would still be great. I admit that the first time I read it, the Peanuts connection went entirely over my head, but everything is so well-scripted and the themes so universal that I loved the story anyway. You don't need to know everything about everyone's histories to understand the fucked up nature of all of their relationships in the present. We've all felt jealousy, hopelessness, and lust. We all have friends we've lost touch with, and others we wish we could. Everybody, at one time or another, takes stock of their lives and feels something comparable to, "Good grief." It's whyPeanuts was and is so popular, and why it deserves this kind of thoughtful, brilliant homage. It's also why Automatic Kafka #4 can be read and adored without any prior Automatic Kafkaor Peanuts knowledge whatsoever.

Then again, understanding the numerous, specific details which Casey and Wood include can only serve to improve the experience. Every page, if not every panel, has a tribute to the source material, a twist on it, and a bit of heartbreak. Even the cover is an allusion to Snoopy battling the Red Baron from atop his doghouse. Automatic Kafka #4 is a poignant and respectful examination of what made Peanuts so great, as well as a mirror held up to the comicstrip's darkest aspects. - comicsmatter.blogspot.com/

This first issue introduces Automatic Kafka, a robotic superhero from a JLA-esque superhero team called the $trangers who disbanded years ago and are either clinging to celebrity status any way they can or are, like Kafka, wasting their lives with drugs and sex.

The surrealistic adventure continues! Agents from the NPS make Automatic Kafka an offer he can't refuse. There are plenty of fun and games with The Warning, and Spastic Ben achieves his ultimate destiny. But is it too little too late? Too much!

In this issue, Kafka turns to drugs specifically designed for use by thinking machines

In a world of bizarre images, none come close to those of Automatic Kafka as a TV game show host. You think reality TV is a kick? Forget everything you know and partake in the madness. You’ll be glad you did!

The world of Automatic Kafka is both familiar and strange, twisted memories of a childhood spent surrounded by adults you could never understand. Just any old blockhead can live in it but it takes more than man's best friend to maneuver through it...trust us.

Introducing the Constitution of the United States...and he's as American as baseball, apple pie and carpet bombing! Automatic Kafka fights for his celebrity as his TV ratings plummet, while the Constitution fights a one-man war for truth, justice and fast food restaurants on every corner!

Now that Automatic Kafka has discovered his drug of choice, it's time to indulge in more carnal pleasures...with a former teammate! Introducing Helen of Troy, holy purveyor of toxic sex-magic. Also, a child's nightmares leads to the arrival of a former $tranger$ adversary.

Who is the mysterious gentleman known as Galaxia? What is his connection, past and future, to Automatic Kafka and the $tranger$? And how does a healthy game of tennis fit into the picture? All this and more as the mystery of the Bank is revealed!

Automatic Kafka makes a life-altering decision that brings him one step closer to discovering "the Secret." But mysteries remain...how much does the Warning really know? Salacious intrigue abounds in the depths of the San Fernando Valley!

How far can a free-thinking, freewheeling android super-hero travel before he sees his own reflection staring back at him? Funhouse mirrors abound in the ultimate search for the strangest secret of them all. Featuring most unlikely guest-stars, as well as special dispensations for every reader who's late to the party.

Tragically, this is the final issue. The cancellation word came down with enough time to prepare to allow writer Joe Casey and artist Ashley Wood to create a story with themselves inserted into it and actually dealing with the Automatic Kafka character they created as they explain to Kafka that he is a comic book character, that he has been cancelled, and why it's better for him to just fade completely into oblivion than to remain in the Wildstorm ether for other writers to later abuse. - www.comicvine.com

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar