Čudesno. Cijela ljudska povijest je muzički instrument.

album preview: soundcloud

Tavaf: soundcloud

www.myspace.com/eyvindkangeyvind

When I interviewed Eyvind Kang back in 2012, he spoke at length about the presence of duality in his music and how that served as a companion to similar reflections and doubles in the world at large: sound and its echo, people and their shadows, music and its reverberations... That theory was already explored on his previous LP with Jessika Kenney, Aestuarium, but resonates much more clearly throughout The Face of the Earth, from its title to the artwork via the cosmic sounds the duo creates across the two sides of vinyl.

As such, an album that, on the surface, appears to be a collection of obscure songs sung in Persian and/or anchored in the Javanese Gamelan tradition may seem a mere curiosity, but repeated listens reveal a multitude of levels and suggested meanings, bringing to mind the age-old metaphor of peeling an onion. It would be easy to see The Face of the Earth as an attempt to present Eastern musics and their inherent philosophies to a Western audience, and there is an element of that. Kenney has long been a student of Gamelan and Persian song, having studied in Indonesia and under famed singer and ney flute player Hossein Omouni. Her strong vocals display a deep understanding of the nature and history of this music, tracing beyond her and Kang’s arrangements towards the foundations of what they are performing. The liner notes speak of “binary” and “reflections from a mirror” and in Kenney and Kang’s hands, the elegant ghazal and kidung songs on The Face of the Earth become reflections of every facet of song art worldwide. Remember, the pair have in the past collaborated -- together and apart -- with the likes of Stuart Dempster, Sunn 0))) and Wolves in the Throne Room, so this is no narrow exercise in intellectual Eastern references. Whilst the duo’s knowledge of the traditions they explore is a fundamental component of the music, The Face of the Earth makes no such demands of the audience, meaning each track is absorbing and effortlessly affecting without the need for further understanding of what’s at play.

The credit for this has to rest with Jessika Kenney, and her wonderfully expressive singing style, aided and abetted by her partner’s spectral music. Kang’s arrangements are sparse, mainly revolving around looped viola and setar (an Iranian lute) lines that mount and descend along elegant melodic structures. This gives a lot of room for Kenney to twist and turn her vocals around the melodies. The singer’s voice is pristine, equally at ease with Javanese and Persian, and particularly emotionally potent when stretching notes in the high register. I may not understand a word she utters, but songs like “Tavaf” and “Kidung” are beautiful, with each line resonating with some inchoate emotional universality. Some tracks are sparse, notably the deceptively epic “Kidung,” which extends over 11 minutes and sees Kenney embark on snake-like vocalizations over the sparsest of plucked viola accompaniment from Kang. It could easily be a patience-defying approach, but with every ululation, cry or whisper imbued with intangible emotion, Kenney owns each and every second.

“Tavaf” and “Mirror Stage,” meanwhile, engage in more elaborate manipulations via looped or multi-tracked vocals and the inclusion of percussion and electronic colorations. Whilst the music is therefore denser, the spirit of the tracks is identical to that of “Kidung,” once again returning to the idea of duality, as if these tracks are extended reflections of the more stripped-down ones. Rapidly repeated loops build up a certain tension, particularly on “Mirror Stage” and the title track, which is immediately countered by the operatic grace of Kenney’s voice, a restlessness that never allows the listener to settle into a single emotive state. That this occurs without any clear direction from Kang and Kenney is entirely to their credit. The duo does not merely engage in pat faux-Eastern mysticism, but rather subtly allows each listener to find his or her way amongst the sounds. By refusing to overtly explain or detail their compositions’ history and intentions, they ultimately give us more freedom to enjoy them, on a level that transcends the boundaries of culture and geography.

- Joseph Burnett

- Joseph Burnett

Sunn O))) guest players and Ideologic Organ mainstays Jessika Kenney and Eyvind Kang return with six new pieces for voice, viola, setar and electronics. Recorded in Istanbul, Seattle and Bologna, The Face Of The Earth is more obviously Eastern in tone to the duo's last IO offering, Aestuarium. Taking its cue from classical Persian and Javanese traditions, and themed around the idea of "drawing the binary from the unary, like reflections from a mirror, and its inverse, the concealed identity", it's a collection of sonic riddles whose meaning can be unlocked, at least to some extent, by the "reading cards" provided in the insert. Despite the arcane mysticism at work, it's music of self-evident and ravishing beauty: from the medievalist balladry of 'Tavaf', to the pensive but restlessly percussive 'Kidung', Kenney's vocal performances are show-stopping throughout, and Kang's strings resonate powerfully around them. Over its short duration, the sparse voice and viola interplay of 'Ordered Pairs II' take on the character of spiritual jazz, while the looping and phasing techniques applied on 'Mirror Stage' come over like a courtly response to Steve Reich's 'It's Gonna Rain', and 'The Face Of The Earth' feels like the logical extension of the more avant-garde moments on Julia Holter's Ekstasis. Tremendous stuff. - boomkat

Last year, I spoke with composer and instrumentalist Eyvind Kang about Aestuarium, the 2005 record he made with his wife, the mesmerizing singer Jessika Kenney. Aestuarium is a quiet album, where seemingly dramatic events happen on mute or in miniature; for Kang, that quality stemmed from observing the slow but busy nature of the estuary near which he and Kenney lived. "There's never a dull moment there," he told me. "Tuning into that was the first act; that was purifying for the next steps that we've taken since then."

"Kidung" is the longest and most immersive piece from the pair's follow-up, The Face of the Earth. The 12-minute piece capitalizes on the promise of Aestuarium by creating an enormous, singular environment that, at first glance, might sound listless. But there's constant motion within Kang's pizzicato viola rhythm and Kenney's strings of beautiful intonation. The parts cooperate, surrounding and supporting each other with ceaseless ease, like the waters and banks of an old river. - Grayson Currin

"Kidung" is the longest and most immersive piece from the pair's follow-up, The Face of the Earth. The 12-minute piece capitalizes on the promise of Aestuarium by creating an enormous, singular environment that, at first glance, might sound listless. But there's constant motion within Kang's pizzicato viola rhythm and Kenney's strings of beautiful intonation. The parts cooperate, surrounding and supporting each other with ceaseless ease, like the waters and banks of an old river. - Grayson Currin

Aestuarium (2005)

Written by Jessika Kenney & Eyvind Kang (1, 3, 4) & traditional (2, 5)

Speculum Magorum by Giordano Bruno.

Speculum Magorum by Giordano Bruno.

Jessika Kenney is a vocalist known for her haunting timbral sense, as well as her profound interpretation of vocal traditions.

Eyvind Kang is a violist for whom the act of music and learning is a spiritual discipline.

Eyvind Kang is a violist for whom the act of music and learning is a spiritual discipline.

Aestuarium is a meditation on a psalm of lamentation and the unary tone in the metaphor of salt and fresh water, inspired by Gaelic psalmery, Tibetan notational gestures, and the microtonality of the tetrachord. Recorded on the shore of Colvos Passage in 2005 by renowned engineer Mell Dettmer.

Stephen O'Malley comments: "Amongst many other amazing pieces Jessika & Eyvind collaborated on SUNN O)))'s "Monoliths & Dimensions" album, Jessika leading the choir on the piece "Big Church" and Eyvind composing the acoustic arrangements for "Big Church" & "Alice". I learned an immense amount about music through these collaborations, specifically the idea of Spectral music through research and discussion/reference points of composers such as Grisey and Murail. Aestuarium is a beautiful piece of minimalist spectral music which has brought great pleasure to my ears over the years."

We knew Ideologic Organ, the new Stephen O'Malley-curated imprint from Editions Mego, was going to throw up some curious releases, and lo, we were right - check out this strange and affecting album, a collaboration between Jessika Kenney and Eyvind Kang - both of whom contributed their acoustic knowhow to Sunn O))'s epic Monoliths & Dimensions LP. It's a selection of unadorned, medievalist ballads - minimalist Spectral music, according to O'Malley - like nothing else we've heard this side of the middle ages, with Kenney's pristine vocals set to the sparsest string accompaniment from Kang imaginable. Kenney is internationally regarded for her haunting timbral register and her interpretations of vocal traditions, while Kang treats music as a spiritual discipline; they describe Aestuarium as "a meditation on a psalm of lamentation and the unary tone in the metaphor of salt and fresh water, inspired by Gaelic psalmery, Tibetan notational gestures, and the microtonality of the tetrachord." Recorded on the shore of Colvos Passage by renowned engineer Mell Dettmer, the album was originally released on CD in 2005 by Endless Records. This is its first airing on vinyl, the definitive edition of a very special, ageless work. - boomkat

When SUNN O))) guitarist and all-round drone/metal/experimental bigwig Stephen O'Malley was handed a curatorial role by Editions Mego to provide the albums for their new Ideologic Organ imprint, it would appear (at least at first glance) that he didn't scout about too far to land his first release, as vocalist Jessika Kenney and violist Eyvind Kang both appeared on SUNN O)))'s monstrous 2009 opusMonoliths & Dimensions, the former directing the choir on 'Big Church', the latter providing string and acoustic arrangements on the same track and on 'Alice'.

But as Ideologic Organ is dedicated to exploring "acoustic" music, in all its varied forms, you'd be wrong to be the expecting saturated guitars, cavernous vocals and doom-laden lyrics that one tends to associate with O'Malley's own musical output. Aestuarium is a work of delicate beauty, as pristine as the surface of a lake at dawn on a summer's morning.

Much of this is down to Kenney's remarkable voice. It glides out of the speakers on opener 'Orcus Pellicano' like a quiet brook sliding down a mountainside. It's clear and immediate, yet steeped in history, seeming to stretch towards the listener from across an ocean of time. Kenney sings in Latin, yet her phraseology seems to come from even further back, echoing traditional music from the pre-Roman Celtic civilisations of Ireland and Britain, steeping Aestuarium in a sense of occult paganism, as if Kenney had, prior to recording, uncovered a grimoire of ancient rites and was using them to channel the spirits of her pre-colonial ancestors. Adapting the musical styles of lost civilisations for the modern times is a particularly treacherous exercise.

But as Ideologic Organ is dedicated to exploring "acoustic" music, in all its varied forms, you'd be wrong to be the expecting saturated guitars, cavernous vocals and doom-laden lyrics that one tends to associate with O'Malley's own musical output. Aestuarium is a work of delicate beauty, as pristine as the surface of a lake at dawn on a summer's morning.

Much of this is down to Kenney's remarkable voice. It glides out of the speakers on opener 'Orcus Pellicano' like a quiet brook sliding down a mountainside. It's clear and immediate, yet steeped in history, seeming to stretch towards the listener from across an ocean of time. Kenney sings in Latin, yet her phraseology seems to come from even further back, echoing traditional music from the pre-Roman Celtic civilisations of Ireland and Britain, steeping Aestuarium in a sense of occult paganism, as if Kenney had, prior to recording, uncovered a grimoire of ancient rites and was using them to channel the spirits of her pre-colonial ancestors. Adapting the musical styles of lost civilisations for the modern times is a particularly treacherous exercise.

It's one thing to cover folk tunes that have been handed down from generation to generation, à la Pentangle or Fairport Convention, but to try and recapture music that has mostly been forgotten, whilst all the while making it palatable for modern sensitivities, is another kettle of fish altogether. Just listen to the bile-inducing fluff of Enya or the Titanic soundtrack for particularly bad examples. On first reading about Aestuarium, I was worried it would sound like a dodgy Dark Ages film soundtrack. Instead, it may just be one of the best modern examples of a minimalist tradition that evidently stretches back into the mists of time, but came to a head from the early-60s-onward with the popularity of Indian masters like Pran Nath and Ravi Shankar, and the emergence of modern composers such as LaMonte Young, Marian Zazeela and Charlemagne Palestine; not so much in the actual style (the pieces on Aestuarium tend to be rather short and airy, as opposed to the lengthy deep drones of Young or Nath), but in the way Kenney and Kang stretch into the past and across borders to create arresting “new” drone and vocal music.

On 'Figura Nox', Kenney brings her interest in Middle Eastern music to the fore, her undulating chanting seeming more indebted to Persian or Maghrebin traditions than the Celtic tones of 'Orcus Pellicano'. This globe-trotting never seems unsettling, though, as the whole of Aestuarium is dominated by the theme of water, from its recording on the banks of Puget Sound to the way it brings in a diversity of influences and phraseologies into one homogenous voice, in the same way cultures crossed oceans to come together in estuarine ports and cities, from Britain to America via Ancient Egypt and The Far East. Aestuarium is ideally suited to being listened to on a vast seashore on a windy day, watching gulls circle over listing cargo ships and choppy waters.

Incredibly, Kenney and Kang (sounds like a detective show duo…) achieve this broad and textured atmosphere with just vocals and viola. Eschewing any predictable call-and-response stereotypes, they combine the voice and strings to become one source, the deeper tones from Kang grounding the soaring vocalisations of Kenney. This is most effective on the spooky, hesitant 'Unnamed Figures', on which the two musicians edge around one another, almost seeming to duel as opposed to duet, both expertly poised, creating a tension that belies their stripped-down set-up. Kenney's voice is mournful and aching, conjuring deep emotions from the sparsest of means. On 'Dies Mei', the loping vocal plays off against a percussive backing line, Kang's virtuosity adding extra dynamism and building on the edginess of the previous track. But by the final piece, (relative) calm is restored. Kang allows himself a rare mini solo which segues into a tremulous vocal by his musical partner. And so the album slides away, like the tide receding from the shore, leaving a sense of having experienced something primal, timeless and haunting. For all that Aestuariumsounds far removed from standard heavy O'Malley fare, it is easy to see what drew him to the album, beyond its obvious beauty. With its impenetrable lyrics, minimal, sparse arrangements and overarching sense of mystery and arcana, it is perfectly keyed in to the same Ur-klang (as Julian Cope would say) that informs the deepest recesses of SUNN O))) and Khanate's music.

But beyond all that, Aestuarium is simply a stirring and beautiful album showcasing two premier musicians advancing into inventive forms of minimalist, but emotionally resonant, music. You can find layer upon layer of meaning in the grooves of this LP, and consider ad infinitum where it fits in the minimalist, or indeed O'Malley, cannons; or you can slap it on, close your eyes, and journey to the wild shorelines Jesskia Kenney and Eyvind Kang conjure up with their intense and beautiful sounds. - Joseph Burnett

On 'Figura Nox', Kenney brings her interest in Middle Eastern music to the fore, her undulating chanting seeming more indebted to Persian or Maghrebin traditions than the Celtic tones of 'Orcus Pellicano'. This globe-trotting never seems unsettling, though, as the whole of Aestuarium is dominated by the theme of water, from its recording on the banks of Puget Sound to the way it brings in a diversity of influences and phraseologies into one homogenous voice, in the same way cultures crossed oceans to come together in estuarine ports and cities, from Britain to America via Ancient Egypt and The Far East. Aestuarium is ideally suited to being listened to on a vast seashore on a windy day, watching gulls circle over listing cargo ships and choppy waters.

Incredibly, Kenney and Kang (sounds like a detective show duo…) achieve this broad and textured atmosphere with just vocals and viola. Eschewing any predictable call-and-response stereotypes, they combine the voice and strings to become one source, the deeper tones from Kang grounding the soaring vocalisations of Kenney. This is most effective on the spooky, hesitant 'Unnamed Figures', on which the two musicians edge around one another, almost seeming to duel as opposed to duet, both expertly poised, creating a tension that belies their stripped-down set-up. Kenney's voice is mournful and aching, conjuring deep emotions from the sparsest of means. On 'Dies Mei', the loping vocal plays off against a percussive backing line, Kang's virtuosity adding extra dynamism and building on the edginess of the previous track. But by the final piece, (relative) calm is restored. Kang allows himself a rare mini solo which segues into a tremulous vocal by his musical partner. And so the album slides away, like the tide receding from the shore, leaving a sense of having experienced something primal, timeless and haunting. For all that Aestuariumsounds far removed from standard heavy O'Malley fare, it is easy to see what drew him to the album, beyond its obvious beauty. With its impenetrable lyrics, minimal, sparse arrangements and overarching sense of mystery and arcana, it is perfectly keyed in to the same Ur-klang (as Julian Cope would say) that informs the deepest recesses of SUNN O))) and Khanate's music.

But beyond all that, Aestuarium is simply a stirring and beautiful album showcasing two premier musicians advancing into inventive forms of minimalist, but emotionally resonant, music. You can find layer upon layer of meaning in the grooves of this LP, and consider ad infinitum where it fits in the minimalist, or indeed O'Malley, cannons; or you can slap it on, close your eyes, and journey to the wild shorelines Jesskia Kenney and Eyvind Kang conjure up with their intense and beautiful sounds. - Joseph Burnett

Originally released on CD-R in 2005, this vinyl only reissue of vocalist Jessika Kenney and violist Eyvind Kang’s collaboration is one of the inaugural releases on Stephen O’Malley’s new Ideologic Organ label. Both artists have worked with O’Malley in Sunn O))) but to expect anything remotely like O’Malley’s own music would be a mistake. This is quiet, contemplative, and fully acoustic; both artists explore the relationships between each others' craft. They intentionally break down the barriers between voice and viola and between playing music and singing.

Thorughout Aestuarium, Kenney’s voice drifts into Kang’s viola like a river into the sea; the two merge into one and become indistinguishable from each other. In the opening moments of "Orcus Pellicano," my ears are bamboozled by this strange symbiosis of timbre. Together, Kenney’s voice and the viola form a third instrument that retains some of the individual character of both instruments but with another dimension that either on its own is incapable of creating. This idea of mixing two similar timbres to form a new middle ground between the two is reflected in the album’s title, an archaic term for an estuary.

Kenney’s interest in Persian music comes through strong on Aestuarium as she explores scales more in line with traditional Middle Eastern music than with western composition. Kang is more than adept both at following Kenney’s lead and in taking the reins himself; at times it is hard to tell who is following who as they almost become one Janus-like figure. On "Unnamed Figures," their respective performances become so entwined that it is hard to believe that one mind is not controlling both musicians. It sounds like Kenney is trying to make Kang play outside his comfort zone and at the same time Kang is pulling Kenney to a point where her voice is tested to its limits.

While I made clear that this is nothing like Sunn O))), it is easy to see why O’Malley would pick this album for his label. Kenney and Kang chase timbre and tone in the same way O’Malley and Greg Anderson do in Sunn O))). In this way, Aestuarium is more than a collection of songs by the duo, here Kenney and Kang have created deeply spiritual as well as conceptual music that could easily have come from a thousand years ago or from 2005. In any case, I wish I had heard this album when it first came out as I feel I have been missing out on something incredible for too long. - brainwashed.com/

Eyvind Kang

Eyvind Kang : Grass

The fifth album for the Tzadik label !!!

Eyvind Kang's newest CD collects quiet new compositions spanning the past five years, which he considers to be among his truly breakthrough works. Music for solo piano, string quintet and more take the unique sonic environments of Morton Feldman to an entirely new place via the metaphors of agricultural poetry, Chinese medicine, sweatlodge, and Ikat weaving. Mesmerizing work from the elusive and ever-stimulating mind of Eyvind Kang!

Featuring: Adrienne Varner, Steve Moore, Taina Karr, Mary Riles, Janel Leppin, Moriah Neils, Eyvind Kang, and Timba Harris.

Released September 25, 2012 byTzadik

Eyvind Kang - Grass - III by Alaraco

Eyvind Kang : The Narrow Garden

While Athlantis is a choral piece inspired by Renaissance era literature and philosophy, The Narrow Garden is inspired by the natural world. “I composed most of the songs at a pond on Vashon Island,” explains Kang. “I also went down to Yelm and Olympia and music just came into my head. There were birds, plants and flowers. It’s a concept of love, of poetry, like a troubadour or ashugh, courtly love that goes in two directions – one the more ineffable, kind of delightful which is the idea of ‘Pure Nothing’ and the other direction is the implication of a kind of violence.”

The Narrow Garden was recorded in Barcelona with a group of 30 musicians conducted by Eyvind Kang, featuring the Embut Ensemble, Jessika Kenney, Jenny Scheinman, Stephanie Griffin, Marika Hughes, Shelley Burgon, Taina Karr, Daphna Mor, Trevor Dunn, April Centrone, etc...

Released January 31, 2012 byIpecac Recordings

Eyvind Kang - 'Pure Nothing' - The Narrow Garden by PardigmMagazine

Eyvind Kang : Visible Breath

Luminescent spectral ensemble music featuring musicians Jessika Kenney, Stewart Dempster, Julian Priester, Cuong Vu, Taina Karr, Timb Harris, Miguel Frasconi, Susan Alcorn & Janel Leppin.

Released 10 January 2012 byIdeologic Organ

curated by Stephen O'Malley, distributed by Edition Mego

Eyvind Kang is not the type to repeat himself. To come to grips with the music of the prolific American composer, arranger, and violinist, you would need to sift through upwards of 50 albums, each with its own secret but palpable internal guidelines. (Lots of them have to do with "NADE," a Sanskrit word with a number of obscure connotations that has a mysterious significance for Kang.) And you would have to range far beyond the composer's own works, through those of Laurie Anderson, Sunn O))), Mike Patton, John Zorn, Marc Ribot, Bill Frisell, and many other hard-to-classify artists. To generalize, Kang refracts strategies from global classical, jazz, folk, and experimental music though his esoteric personal interests, which are always changing. He's a musical polymath who writes in his own voice instead of self-consciously "crossing genres." Boundaries are aren't smashed, but simply ignored, dreamily melting away.

The Narrow Garden features an exotic array of strings, winds, horns, and percussion, performed by an international cast of more than 30 musicians from three different ensembles. Written at home, on an island near Seattle, but partially recorded in Barcelona, the record purports to explore the medieval concept of courtly love. We all know that "explores the concept of" often boils down to "mentions in the liner notes," but you don't have to strain too hard to hear Kang's intricate weaving of soft, romantic consonances and harsh, anxious dissonances as an expression of the quicksilver joys and miseries of formalized desire. Taking in lyric poetry, Western choral music, Middle Eastern and South Asian modes, and "ashugh" singing (a popular folk tradition heavily associated with the Caucasus), The Narrow Garden features some of the most sunny and flowering music that Kang has created, seamlessly joined with a couple of sinister threnodies. If the Middle East-tinged jazz of Wyatt, Atzmon & Stephen's For the Ghosts Within had been aggressively produced by Svarte Greiner, it might have come out like this.

At one extreme, there are ravishing compositions of deceptive simplicity, which accumulate delightful embellishments. These include "Pure Nothing" (a sultry setting of a Guilhem IXpoem translated into English by W.S. Merwin) and "Forest Sama'i", where a serpentine melody seems to hover over Eastern and Western classical modes without alighting on either one; the playful variations unfold until the song abruptly takes flight in a scherzo-like dance animated by trembling whistles. At the other extreme are the title track and "Usnea": dense, metallic braids of screeching strings, ear-spearing flutes, and other distressed timbres. Kang knows how to sculpt and compress clashing harmonies until they take on an inviolable collective form, like a perfect cube of mangled cars fresh from a compactor. But the best thing about the record's tonal variety is how neatly it all blends together, especially on epic closer "Invisus Natalis", where a fleet of guitars, basses, strings, and bassoons taper down to a liquid cacophony, dissolving all of Kang's thought-provoking musicological contrasts into a flawless, golden glow.

The term “renaissance man” is tailor made for an artist like Eyvind Kang. He’s a prolific composer, multi-instrumentalist, and frequent guest star, lending his unique contemporary-classical style to collaborations with indie rock stalwarts Blonde Redhead and experimental icons Sun City Girls among dozens others. It’s on solo efforts like The Yelm Sessions, released in November on Tzadik, where his vision and talent can truly be appreciated.

Eyvind Kang’s Journey Through The Yelm Sessions

The term “renaissance man” is tailor made for an artist like Eyvind Kang. He’s a prolific composer, multi-instrumentalist, and frequent guest star, lending his unique contemporary-classical style to collaborations with indie rock stalwarts Blonde Redhead and experimental icons Sun City Girls among dozens others. It’s on solo efforts like The Yelm Sessions, released in November on Tzadik, where his vision and talent can truly be appreciated.

“I’ve been working on it for three years,” Kang says of the album. “I didn’t set out to record everything as a whole; it’s more like an album of different ideas and experiences I had over that time that in retrospect had a sequence. There was a reason that it fit together.”

The Yelm Sessions is a flowing, epic production that shows off Kang’s classical training and progressive spirit, marrying orchestral flourishes with delicate chamber music and groaning, screeching jags of sound or subtle electronic augmentation. The album’s layered mélange of influences is the result of a European excursion through Rome and Vienna on which many of the tracks were recorded. Kang attributes the ethereal mood of The Yelm Sessions to the trip. “It’s the feeling of traveling and coming home, and all of the experiences you have in your memory. You return home and years later something triggers the memory—a feeling or the smell of a bakery—and there’s a weird longing that you feel. I wanted to make the music like that—very dreamlike, a musical travelogue.”

Songs like “Enter the Garden” and “Asa Tru” paint gorgeous aural landscapes, but Kang’s journey isn’t limited to the beautiful and the picturesque. “Hawks Prairie” is dark and predatory, like something out of a medieval black forest where the imagination conjures danger in every shadow. The looming dread is broken only by the harsh drag of a bow across violin strings, squealing and screeching, like the song itself is being gutted. It’s a harrowing experience, yet impossible to skip.

Kang draws particular influence on The Yelm Sessions from the baroque melodies of J.S. Bach and the romanticism of Anton Bruckner. One can detect the slightest threads of Philip Glass on the arpeggiated backdrop of the title track. “Mistress Mine” borrows lyrics from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, continuing a dialogue with the Renaissance that Kang began on last summer’s Athlantis (Ipecac), on which he utilized the writings of Giordano Bruno. “Bruno was a martyr; he was burned at the stake,” Kang reveals, referring to Bruno’s support of science and condemnation for heresy. “His writing and subject matter is up my alley, and he has a great sense of humor. I feel like I’m friends with these guys.”

Much like how the works of Bruno and his contemporaries have sparked Kang’s creative energies, he hopes that The Yelm Sessions serves as inspiration to others. “I want to open doorways to neurons,” he says, “not to affect people in a particular way but to help them find their own feelings and emotional response.” To that end, Kang has provided a potent and provocative album that’s just waiting to unlock those doors for those willing to listen. -Michael Patrick Brady

Collaboration Albums › › ›

Mark O'Leary, Eyvind Kang, and Dylan Van Der Schyff -

Zemlya

(Leo Records - 2008)

William Hooker with Eyvind Kang and Bill Horist -

The Seasons Fire

(Important Records - 2007) < audio sample >

Billy Martin & Socket -

January 14 & 15 2005

(Amulet Records - 2005)

Eyvind Kang & Tucker Martine -

Orchestra Dim Bridges

(Conduit Records - 2004) < audio sample >

Napoli 23 -

Eyvind Kang, Hilmar Jensson, Skuli Sverrisson, and Matthias M.D. Hemstock

(Smekkleysa - 2002) < audio sample >

Amir Koushkani with Eyvind Kang -

In The Path Of Love

(Golbarg - 2001)

Eyvind Kang, François Houle, and Dylan van der Schyff -

Pieces of Time

(Spool - 1999)

Michael Bisio & Eyvind Kang -

MBEK

(Meniscus - 1999)

Dying Ground: Live at the Knitting Factory -

Eyvind Kang, Kato Hideki, and G. Calvin Weston

(Avant - 1999)

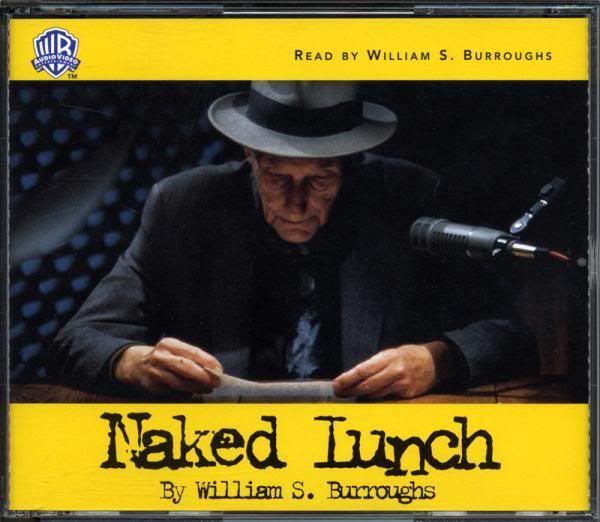

Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs -

Music by Bill Frisell, Wayne Horvitz, and Eyvind Kang

(Warner - 1995)Beyond Fahey

How acoustic guitarists are shedding the shadow of John Fahey, plus interviews with Eyvind Kang, Burmese, and Erik Friedlander.

By Marc Masters and Grayson Currin

II. Eyvind Kang: A Greater Awareness

Photo by Jerry Morrison

Aestuarium is a 2005 collaboration between composer and multi-instrumentalist Eyvind Kang and his wife, the stunning vocalist Jessika Kenney. Sunn O))) member Stephen O'Malley recently re-released Aestuarium on Ideologic Organ in collaboration with Editions Mego. Kenney, Kang, and O'Malley are familiar collaborators, as Kenney led the choir and Kang composed many of the orchestral parts for Sunn O)))'s most recent work, Monoliths & Dimensions.

But this isn't doom metal. Aestuarium moves with tiny swells and builds through delicate melodies, Kenney's operatic fantasies wrapping like tendrils around Kang's restrained violin work. Recorded at the couple's home along a Puget Sound estuary, it's an environmental statement that's more pleasant than polemical.

We caught Kang in his hotel room in Calgary where he was teaching after wrapping up a series of festivals and collaborations across Europe. He and Kenny were soon due to head into the Canadian mountains to observe and relax. "Life has been pretty hectic for at least six months," he says, sighing. "We're going to take a little time."

"Dies Mei":

Eyvind Kang: Dies Mei

Pitchfork: You're in Calgary now, where they're ripping oil from the sand to the north. You were just in Iceland during the volcano. And Aestuarium is a record that touches on your relation to nature. What's your feeling about the state of our environment and your role as an artist?

Eyvind Kang: It's a big deal, man. This morning, I woke up and was walking on a mountain, and I thought, "What's the worst thing that humans could do to the planet? Make it uninhabitable for humans and kill wildlife." I suddenly didn't feel so bad. It's terrible, but 100,000 years is how long it takes radioactive waste to decay. It is outside of what we know as human history, but geologically, it's not too significant. There's a lot of time before the sun burns out. In our life times, though, we have to do what we can. We have to stop abusing nature like this. It's unfuckingbelievable.

"Jessika and I want to explore musical ideas that also have a practical relevance in terms of ecological work."

But, at the same time, getting into environmentalism can be too depressing and hysterical. Musicians always want to sacrifice our creativity to get involved in environmental issues or political activism of some sort-- to reduce it to something more populist in terms of sing-alongs or guitar songs with a message. That goes against the depths of what we're actually able to do creatively. Jessika and I want to explore musical ideas that also have a practical relevance in terms of ecological work. What happens in our consciousness and minds and bodies is also happening on earth. The more we pollute the earth, for example, the sicker we are.

Pitchfork: How might the musical exploration of those issues sound?

EK: Aestuarium is a good example of that. The estuary was our home; we recorded that at home. It's really all about the water. We weren't really starting from the point of view of, "Look at this water. It's so polluted. We should do something about it." That didn't come into the conversation at all, even though it's true of the Puget Sound, which is horribly polluted. What we were looking at was the flow of the fresh water from an island, which was our home, into the salt water. That area where it's combined is where we actually live. Living in a place like that, you see that there are more than ducks and other species of aquatic life that are attracted to the estuary. It's a certain type of people, certain kind of spirits. There's a lot of action. There's never a dull moment there. Tuning into that was the first act; that was purifying for the next steps that we've taken since then. Water is the most purifying element. It's always involved in baptisms, healings, that kind of work.

"I love the appropriateness of making a dogmatic statement. I support that, but that is a different level of the individual consciousness than was the source of our music."

Pitchfork: You talked about not reducing your creativity to singer-songwriter fare to support a cause. Is that because you see that as too dogmatic or because your thoughts on such topics are too personal?

EK: I would say neither. Our individual consciousness is actually part of a larger system. There are many levels of consciousness, and the creativity used in composing the music comes from another level that is not purely personal. We composed stuff together; we had an idea of how the melodies would form themselves. In a way, composing on the melodic level is an expression of a melodic truth, almost like a geometric truth. If it has clarity, other people will recognize it. There's no way of isolating it in a gallery on a white wall and saying, "This is a work of art. This is a mathematical proof."

In terms of dogma, we're not really interested in that. There's a time and place for that; I love the appropriateness of making a dogmatic statement, but we weren't even thinking about those things four years ago. The subject matter was clean water itself.

Pitchfork: You and Jessika have worked on so many important projects together, from Sunn O)))'s Monoliths & Dimensions to Aestuarium. When did you realize the chemistry and special bond you two had?

EK: From the beginning. When we first met, we had so much to talk about. There was so much research that we were both doing. It's been a constant process. Aestuarium was a big signpost along the way in defining that path. A lot has happened since then. Both of us were involved in traveling whenever we could by any means to do musical research. She spent so much time in Java; I was in India. That took an incredible amount of effort, and not a lot of people I knew of had done that. It was also at considerable personal risk, too. Never underestimate that: When you make a trip like that, do you know if or when you're ever going to return?

But that's life, and we did return. We got married, and we started going into the deeper work, the inner work. It opened a lot of doors and removed a lot of obstacles that we didn't even know were there. It's a process, and it keeps evolving in ways that are surprising to me. There's a lot of magic involved, but I can't put too fine of a point on it. It's what we both want to be doing.

We haven't done a lot of performing with just the two of us because it's such inner work. But I think it's cool because O'Malley and some other people picked up what we were up to. But now, we really want to flip the script and go out and do more performances dedicated to the world on an ecological, cosmological level. We put in a lot of time for our inner work, now we want to do outer work. We've discovered a lot of processes, and we've built up quite a repertoire. We see ways of going forward.

"There is no guiding principle, because the work that is created in collaborations should be created from its own principles."

Pitchfork: Are there any specific works you two have in mind for the near future?

EK: One collaborative process that I can mention is working on the level of linguistics.Aestuarium is a good example of that, too, because working with the Latin language is pretty powerful for both of us. Working with a language that is not spoken vernacularly is intense. There are other works of poetry and text where we get pretty deep into bringing out the essence of the syllables and letters and how they work. You can't just push around text and recite it or cut it up. I don't like to treat words and sounds like objects. You have to penetrate deeply into their meaning. We're working with other people on that level. Linguistic work is group work. Even if you're a genius and you invent your own language, it doesn't become a language until there are people using it.

Pitchfork: What aspect of those sorts of texts do you like most?

EK: The most appealing part is the feeling of learning something true-- the pleasure of a truth. For me, that's mostly found in philosophical literature at the moment. The subject matter doesn't change that much in philosophy, so when you're reading something from 2,000 years ago in ancient Greece, it works. I love the pleasure of finding the same truth in two different places. It has a lot to do with a soul.

"Unnamed Figures":

Eyvind Kang: Unnamed Figures

Pitchfork: You collaborate so often and with so many people: Is there a single guiding principle or framework that you take into each of those?

EK: There is no guiding principle, because the work that is created in collaborations should be created from its own principles. Who approaches collaboration with agenda in terms of content? The agenda is only in terms of process, which is generosity, listening, careful thinking.

Pitchfork: So you let listening guide you through each work more than any idea?

EK: Yes, learning how to listen to others and how to listen to your own thoughts is the ultimate process. Artaud said that the worst pain is to feel your thoughts slipping away from you. I think I know what he's talking about. Listening is active. It's like vision. It's like the idea of the eye projecting light, which I've heard is what children and infants say when they're asked to explain vision-- that the eye projects light, rather than just receives it.

I think listening is similar because you project from your ears onto something. There's a big interaction in between the ear and the mind, a gap. Maybe that's where the creative work-- especially in collaboration-- comes forth. With composing or creating art, you're always projecting outward. You tend to visualize it as modeled on the individual thought-- me, my identity, I am, I am thinking. It's Cartesian. You project your personality and your idea to some form of writing or recording. With collaboration, it's more of a group experience.

Here's an example: When you're listening to music, you listen to it with a friend one day and it sounds one way. You listen to it with another friend the next day, and it sounds a little different. Sometimes the greatest pleasure of listening is not the music that you're listening to; it's the person that you're listening to it with. That is collaborative listening. When you sit with people and you can hear what they're hearing, that's quite interesting.

"All these emotions are coming from one thing-- sound. It's not coming from your experiences in life, your childhood. It's related to those things, but it's being triggered by the sound."

Pitchfork: In an interview with The Wire, you said that you preferred not to think about music in terms of dark and light. What's the problem with using that archetype for you, and what model do you prefer in dealing with emotion in music, if any?

EK: The problem is, it's too superficial. It doesn't deal with the content. It's like saying a major chord is happy and a minor chord is sad. It's kind of pathetic, to be reduced to terms like that when you're dealing with something like music. The other problem with dark and light is that it's mostly about our other baggage, our associations. Maybe somebody used this piece of music in a film that had a plot about murders, so this music is used in a very scary way. I like to think about a story I heard about Feldman asking Stockhausen, "Yeah, you compose a lot of scary music, but do you compose any music that scares you yourself? If that was true, then you could speak to this being scary." In a way, all recorded music is reduced to the same level, no matter what it is. You find it in the store, you put it on and, "Oh, that's not cool. That's gangsta rap. That's white supremacist punk." But in a way, the content is removed from the intention of the people that made it. That's the commercial level of music.

But putting all that aside, I think the question of actually relating emotion to music is totally interesting. I believe that it is really important on some level, but it's also important not to impose your own emotions on some music that has its own emotions. That theory in Indian music, they call rasa-- actually, it's all over the pulse of Buddhist framework. It means emotions, and it's pretty complicated. There are a lot of emotions, and that's one of the projects I'm working on during the act of playing improvisation. If you see old footage of Glenn Gould, for example, watch how much he feels. That's on the level of yoga, when you feel this tremendous surge of energy, like when you say your blood boils or your heart beats faster. All these emotions are coming from one thing-- sound. It's not coming from your experiences in life, your childhood. It's related to those things, but it's being triggered by the sound. It's physical, like acupuncture, a release of energy from inside. That's different from dark and light. There is some music that's truly dark, in that it's dark in terms of hopeless. But then again, the act of hope is just making the work of art.

Pitchfork: So creation in and of itself is hope, no matter how "dark" or "light" something sounds?

EK: Yeah, that is the hope, absolutely. --Grayson Currin

“Seems like the memory forms a shell around the event, or the person … then the process of remembering becomes just the memory. The next time, it’s the memory of the memory and so on; in order to know, to live, you have to forget, you can’t remember everything all the time.” -Eyvind Kang

Introduction & Interview Theo Constantinou

Instead of introducing this interview, I will attempt to answer the questions Eyvind asked of me during our interview.

Who are you?

Eyvind, my name is Theo Constantinou; a 26 year old seeker of knowledge living in Philadelphia.

Are you a writer, or what do you do?

I am not a writer, and have no formal training in writing whatsoever. I publish Paradigm Magazine in the hope to inspire people all over the world through the interviews, editorials, photographs and artwork that are published on our site.

How do you find a great teacher?

I was not sure how I met Nicolas Constantinidis, so I just called my mother to have her tell me the story. She said I had not been cooperating, and was quite defiant with my other piano teacher, so she took it upon herself in finding someone that would motivate me. She had heard about this blind man who was well known in the area and asked him if he would work with me. He told her that he had to meet me first, before he would work with me: I was 12 years old. We met at his home, talked at great length, and the rest is history.

What kind of interview is this?

Eyvind, I don’t even want to think of this as an interview; more of a conversation that pushes the scope of what people are willing to talk about and, an introspection into the individual that we are talking to. Like our magazine, these deep philosophical conversations will hopefully inspire the reader to take action in their lives to create positive change, and think about new perspectives and realities.

Doesn’t everyone think about death and nothingness?

Unfortunately, not enough people think of death and nothingness. It is their personal fear of their own shadow, and inevitable demise, that they hide from instead of facing it truthfully and embracing their fate, while constantly pushing themselves in this life as far as they can with the limited amount of time that they have.

_________________________________________________________________________________

I read that, “Kepler considered the Harmonices Mundi (1619) his greatest work. The text relates his findings about the concept of congruence with respect to diverse categories of the physical domain: regularities in three-dimensional geometry, the relationships among different species of magnitude, the principles of consonance in music, and the organization of the Solar System.” What did Kepler’s work teach you, and how do you use his theory in creating your own music?

Hello, and thanks for bringing up these interesting questions. Who are you? Are you a writer, or what do you do? Myself, I’m a musician who reads many books, but that is not the best way to learn something. To be honest, I’ve never used Kepler or any other theory in music; I don’t even study physics very much. Like many musicians, I looked for models that helped to comprehend musical experiences, and was always attracted to the old image of Music of the Spheres, but stopped short of celestial mechanics. When it comes to Solar systems, the Harmonia Mundi describes a tuning theory in terms of geometry, which also relates to poetic in the sense of microcosm to macrocosm. Actually, the outer space and the inside of an atom could be the same as far as I’m concerned. It’s nothing without the poetical side, which Pythagoras was already bored of, but seems to remain at the forefront of our musical procedures…even if only through the invocation of the Muses within the proper name. It’s just that the whole sphere of sciences tend to give us more context for the poetic side.

You were quoted in an interview stating that, “In alchemy, one of the main steps is to descend into the chaos, called ‘nigredo,’ and then to let a kind of order manifest itself from that chaos. So I followed that idea, not the idea of an authority person imposing the order from above; in other words, a kind of anarchy.” Can you speak to me more about this idea of chaos and anarchy in your approach to music?

Sure, but I guess the paradox is that it should never become an “arche,” or principle. What is interesting also, from a viola standpoint, the bow, or “arco” -that is what makes everything sound; whereas, the action of the left hand is more or less silent, unless activated by the arco, arche or principle. Our arco is related to the mare’s tail, or the Earth. Ultimately, the Earth is what grounds all these experiences and makes them grow. To cultivate that through land, through social interactions, brings up questions of a political hue. Sometimes they used to burn ashes, and make that fertilize the soil – like black Earth in the Amazon jungle. When trying to learn music, we grow, study, but also need to let go, to forget – this is very important.

There are portions of Plato’s Timaeus that I find quite interesting and my understanding of them is something that I am still trying to grasp … I would love to hear your interpretation of these excerpts, either as they stand alone or as a whole, and how they relate to your life and your creative process?

Some things always are, without ever becoming (27d6).

Some things become, without ever being (27d6–28a1).

If and only if a thing always is, then it is grasped by understanding, involving a rational account (28a1–2).

If and only if a thing becomes, then it is grasped by opinion, involving unreasoning sense perception (28a2–3).[17]

The universe is a thing that has become (28b7; from 5a–c, and 4).

Anything that becomes is caused to become by something (28a4–6, c2–3).

The universe has been caused to become by something (from 5 and 6).

Amazing question, but the format here is too brief to really answer. What kind of interview is this? These excerpts that you’ve lined up show how the typical dialectic that gets made between Being and Becoming can lead to a concept of causality that is so linear, one can go on from there to sort of prove the existence of first cause, prime mover, or what have you…which may seem quaint but was developed in an interesting way by the Scholastics, analytics, etc. It brings up many paradoxes – axiomatic reasoning by itself has to be supported by principles too, so it easily becomes circular. You have to name something: first, second, third, fourth, fifth, etc. What we normally call music, is usually just the presentation of music, so we get into the same problems in our ontology. I don’t want to join any category of perceptual music, but at the same time, I don’t really believe in a particular perennial sound. If you have a sound, you have another sound, you have an octave, you have a 5th, a 3rd, and so on: the whole harmonic series; so you get all the natural numbers right off the bat. From there, you can get your incommensurates, to the chagrin of Timaeus and company, and on to the transfinite and beyond. At the same time I wonder, if Being and Becoming could both be part of the same, like stillness and rest in the Chinese “I” or “change” – as in “change is unchangeable” – wouldn’t that make things a lot clearer? So, infinitely more interesting to me than the Pythagorean Timaeus, is the Parmenedes.

I read that you won’t disclose the meaning of ‘NADE,’ Can you tell me more about the principles or driving forces of NADE without disclosing its direct meaning?

It’s not that I didn’t want to disclose it, but just that it didn’t mean anything. Nowadays, I’m interested in sound itself, to be honest. How do you approach it? The Guidonian hand, the letter names…the various points and stems in music writing are constructions which seem to represent notes; to a bird they could sound like melodies, to an insect maybe they sound like a whole genre, to a rock or sand, it sounds like nothing at all. So all these sounds are nothing in a way, but they could become anything, like in a sudden dream.

Nearly a decade ago, I studied classical piano from a blind man, and that experience and lessons still impact me to this day … Can you talk more about the influence and impact of your studies with the great violinist, Dr. N. Rajam?

Certainly. How do you find a great teacher? You can’t just “sign up.” And then, it’s not a walk in the park; you know from your piano experience, every musician knows, and when it comes to violinists, we know. Michael White: great violinist; he basically prepped me for the larger encounter with the bowed string, oriented me to his principles concerning the nature of music to be healing, to be spiritual, that kind of thing. There was no technical discussion or any pedantry, just the positive intention, the creative theosophy, which you find in jazz, especially of Michael’s generation, vis, the Coltranes, Sun Ra, Pharoah, Fourth Way, etc. Dr. N. Rajam is one of the other great teachers I met and worked with. The question at hand was “raga” – but as with any teacher, there were some secrets which could be learned by transmission only. I worked with her for only four short months, long years ago, so its nothing, really; nothing about Indian classical music, I don’t claim that. But for me, she’s always there, every time I play the instrument. Also, there is a current from her teacher, Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, which affects me in my studies. I really can’t describe the devotion I feel towards them.

I recently revisited the film The Seventh Seal by Ingmar Bergman, and found this dialogue quite fascinating … Why do you think that most people don’t seek knowledge, and neither think of death or nothingness?

Antonius Block: I want knowledge! Not faith, not assumptions, but knowledge. I want God to stretch out His hand, uncover His face and speak to me.

Death: But He remains silent.

Antonius Block: I call out to Him in the darkness. But it’s as if no one was there.

Death: Perhaps there isn’t anyone.

Antonius Block: Then life is a preposterous horror. No man can live faced with Death, knowing everything’s nothingness.

Death: Most people think neither of death nor nothingness.

Antonius Block: But one day you stand at the edge of life and face darkness.

Death: That day.

Antonius Block: I understand what you mean.

Doesn’t everyone think about death and nothingness? I guess thinking about it is natural, but talking about it is not too easy.

One of my favorite poets, Constantine Cavafy has a poem called ‘Long Ago’ … You described ‘Narrow Garden’ as, “a concept of love, of poetry, like a troubadour or ashugh, courtly love that goes in two directions.” The poem is below; I am curious to hear your thoughts on memory specifically about people who you have loved in your life and are now gone, are they just faded memories to you now?

Hello, and thanks for bringing up these interesting questions. Who are you? Are you a writer, or what do you do? Myself, I’m a musician who reads many books, but that is not the best way to learn something. To be honest, I’ve never used Kepler or any other theory in music; I don’t even study physics very much. Like many musicians, I looked for models that helped to comprehend musical experiences, and was always attracted to the old image of Music of the Spheres, but stopped short of celestial mechanics. When it comes to Solar systems, the Harmonia Mundi describes a tuning theory in terms of geometry, which also relates to poetic in the sense of microcosm to macrocosm. Actually, the outer space and the inside of an atom could be the same as far as I’m concerned. It’s nothing without the poetical side, which Pythagoras was already bored of, but seems to remain at the forefront of our musical procedures…even if only through the invocation of the Muses within the proper name. It’s just that the whole sphere of sciences tend to give us more context for the poetic side.

You were quoted in an interview stating that, “In alchemy, one of the main steps is to descend into the chaos, called ‘nigredo,’ and then to let a kind of order manifest itself from that chaos. So I followed that idea, not the idea of an authority person imposing the order from above; in other words, a kind of anarchy.” Can you speak to me more about this idea of chaos and anarchy in your approach to music?

Sure, but I guess the paradox is that it should never become an “arche,” or principle. What is interesting also, from a viola standpoint, the bow, or “arco” -that is what makes everything sound; whereas, the action of the left hand is more or less silent, unless activated by the arco, arche or principle. Our arco is related to the mare’s tail, or the Earth. Ultimately, the Earth is what grounds all these experiences and makes them grow. To cultivate that through land, through social interactions, brings up questions of a political hue. Sometimes they used to burn ashes, and make that fertilize the soil – like black Earth in the Amazon jungle. When trying to learn music, we grow, study, but also need to let go, to forget – this is very important.

There are portions of Plato’s Timaeus that I find quite interesting and my understanding of them is something that I am still trying to grasp … I would love to hear your interpretation of these excerpts, either as they stand alone or as a whole, and how they relate to your life and your creative process?

Some things always are, without ever becoming (27d6).

Some things become, without ever being (27d6–28a1).

If and only if a thing always is, then it is grasped by understanding, involving a rational account (28a1–2).

If and only if a thing becomes, then it is grasped by opinion, involving unreasoning sense perception (28a2–3).[17]

The universe is a thing that has become (28b7; from 5a–c, and 4).

Anything that becomes is caused to become by something (28a4–6, c2–3).

The universe has been caused to become by something (from 5 and 6).

Amazing question, but the format here is too brief to really answer. What kind of interview is this? These excerpts that you’ve lined up show how the typical dialectic that gets made between Being and Becoming can lead to a concept of causality that is so linear, one can go on from there to sort of prove the existence of first cause, prime mover, or what have you…which may seem quaint but was developed in an interesting way by the Scholastics, analytics, etc. It brings up many paradoxes – axiomatic reasoning by itself has to be supported by principles too, so it easily becomes circular. You have to name something: first, second, third, fourth, fifth, etc. What we normally call music, is usually just the presentation of music, so we get into the same problems in our ontology. I don’t want to join any category of perceptual music, but at the same time, I don’t really believe in a particular perennial sound. If you have a sound, you have another sound, you have an octave, you have a 5th, a 3rd, and so on: the whole harmonic series; so you get all the natural numbers right off the bat. From there, you can get your incommensurates, to the chagrin of Timaeus and company, and on to the transfinite and beyond. At the same time I wonder, if Being and Becoming could both be part of the same, like stillness and rest in the Chinese “I” or “change” – as in “change is unchangeable” – wouldn’t that make things a lot clearer? So, infinitely more interesting to me than the Pythagorean Timaeus, is the Parmenedes.

I read that you won’t disclose the meaning of ‘NADE,’ Can you tell me more about the principles or driving forces of NADE without disclosing its direct meaning?

It’s not that I didn’t want to disclose it, but just that it didn’t mean anything. Nowadays, I’m interested in sound itself, to be honest. How do you approach it? The Guidonian hand, the letter names…the various points and stems in music writing are constructions which seem to represent notes; to a bird they could sound like melodies, to an insect maybe they sound like a whole genre, to a rock or sand, it sounds like nothing at all. So all these sounds are nothing in a way, but they could become anything, like in a sudden dream.

Nearly a decade ago, I studied classical piano from a blind man, and that experience and lessons still impact me to this day … Can you talk more about the influence and impact of your studies with the great violinist, Dr. N. Rajam?

Certainly. How do you find a great teacher? You can’t just “sign up.” And then, it’s not a walk in the park; you know from your piano experience, every musician knows, and when it comes to violinists, we know. Michael White: great violinist; he basically prepped me for the larger encounter with the bowed string, oriented me to his principles concerning the nature of music to be healing, to be spiritual, that kind of thing. There was no technical discussion or any pedantry, just the positive intention, the creative theosophy, which you find in jazz, especially of Michael’s generation, vis, the Coltranes, Sun Ra, Pharoah, Fourth Way, etc. Dr. N. Rajam is one of the other great teachers I met and worked with. The question at hand was “raga” – but as with any teacher, there were some secrets which could be learned by transmission only. I worked with her for only four short months, long years ago, so its nothing, really; nothing about Indian classical music, I don’t claim that. But for me, she’s always there, every time I play the instrument. Also, there is a current from her teacher, Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, which affects me in my studies. I really can’t describe the devotion I feel towards them.

I recently revisited the film The Seventh Seal by Ingmar Bergman, and found this dialogue quite fascinating … Why do you think that most people don’t seek knowledge, and neither think of death or nothingness?

Antonius Block: I want knowledge! Not faith, not assumptions, but knowledge. I want God to stretch out His hand, uncover His face and speak to me.

Death: But He remains silent.

Antonius Block: I call out to Him in the darkness. But it’s as if no one was there.

Death: Perhaps there isn’t anyone.

Antonius Block: Then life is a preposterous horror. No man can live faced with Death, knowing everything’s nothingness.

Death: Most people think neither of death nor nothingness.

Antonius Block: But one day you stand at the edge of life and face darkness.

Death: That day.

Antonius Block: I understand what you mean.

Doesn’t everyone think about death and nothingness? I guess thinking about it is natural, but talking about it is not too easy.

One of my favorite poets, Constantine Cavafy has a poem called ‘Long Ago’ … You described ‘Narrow Garden’ as, “a concept of love, of poetry, like a troubadour or ashugh, courtly love that goes in two directions.” The poem is below; I am curious to hear your thoughts on memory specifically about people who you have loved in your life and are now gone, are they just faded memories to you now?

‘Long Ago’ by Constantine Cavafy

I’d like to speak of this memory, But it’s so faded now – as though nothing’s left – Because it was so long ago, in my adolescent years.

A skin as though of jasmine . . . That August evening – was it August? – I can still just recall the eyes: blue, I think they were . . . Ah yes, blue: a sapphire blue.

Seems like the memory forms a shell around the event, or the person … then the process of remembering becomes just the memory. The next time, it’s the memory of the memory and so on; in order to know, to live, you have to forget, you can’t remember everything all the time. The function of time consciousness doesn’t really condition the experience of love, or of a person’s soul. Thanks again, and take it easy! - paradigmmagazine.com/

Eyvind Kang: Continuity, Innovation, Liberation

Photo of Eyvind Kang by Bryce Davesne

By Schraepfer Harvey

He makes those explorations with an ever-expanding list of collaborators: Shahzad Ismaily, Hans Teuber, Christian Asplund, Tucker Martine, Tari Nelson-Zagar, Timothy Young. On his most recent Ipecac Recordings release, The Narrow Garden, Kang directs thirty ensemble members in different configurations, exhibiting what’s quintessentially Kang, a mix of diverse instruments and timeless musical palettes from cultures around the globe. I caught up with Kang by phone in December and ran into him at the Royal Room opening weekend, where he performed with Scrape. We covered a couple of his jazz influences – Ornette Coleman and early violinist Stuff Smith: “There’s a person that plays with guts.” We also talked about Kang’s time with Michael White, the former Bay Area violinist with a handful of Kang-recommended releases on Impulse! from the early 70s and a 1997 release with Bill Frisell, Motion Pictures. We also talked about his continuing explorations into music around the world and of his recent Artist Trust Arts Innovator Award, a $25,000 gift to two generative artists each year. Here’s a statement from Artist Trust Executive Director Fidelma McGinn: “Thanks to The Dale and Leslie Chihuly Foundation’s support, Artist Trust’s Arts Innovator Award is open to Washington State artists of all disciplines who are originating new work, experimenting with new ideas and pushing the boundaries in their respective fields. The selection panelists felt that Eyvind stood out this year among an impressive group of high-caliber entries. They felt his unique approach to his musical composition deserved to be rewarded. He has had a great impact on the jazz scene on both a local and national level, and will undoubtedly have a bigger impact in years to come.” Whatever you make of Kang’s impact on the jazz scene, the Artist Trust award is money and sanction from a local authority that has lent recent spunk to current Kang projects, like a recent collaboration with cellist Janel Leppin and pedal steel player Susan Alcorn and instrumentalist and vocalist Jessika Kenney, also Kang’s wife. “I was totally surprised,” he says. “It gave a lot of positive energy to things I couldn’t decide if I wanted to commit to … I was really lucky to get that.” Kang’s innovation is his authentic and personal search, with a variety of musicians, often absent of commercial success or large-scale administrative support. In his career, he hasn’t waited for signs of approval. “I’m in a time warp, I think. I’m still doing the same thing,” he says. It’s that search that is the inspiration for generations to come. He describes to me some of his teaching goals from his 2011 faculty experience at the Banff Centre: “I was trying to concentrate on creative approaches to technique.” He explains that creativity is pre-lingual and advises students not to get trapped. “It’s the minutia of what angle your finger is going on the string,” for example. In a performance setting, the key is internally freeing yourself to a point where that awareness is so internalized that reactions of all kinds become accessible to you at an instant, as opposed to conventional or clichéd responses or responses that are simply built into your training or the way you practice or your body’s memory. It’s a discovery he’s made from travels and musical experiences around the world and with teachers Dr. N Rajam, in Mumbai, India, and Ustad Hossein ‘Omoumi, formerly of Seattle via Iran, now in California. Since, minutia is paramount for Kang, and perhaps an unsurprising quest for a string player. Styles for violin are so diverse, yet the canon so limited for us here – jazz, bluegrass, Western classical, Irish. But, Kang says, “I have to deal with all the different cultures and traditions. Once you know, you can’t ignore it … that’s what bounces back to me as a composer.” Coloring his compositions and releases over the last decade are diverse musical references. Kang points out, “I don’t think there’s different music; there’s different systems.” The West often turns to even temperament. “Viola and violin have freedom to play a lot of tunings, but we have to play with the piano,” Kang says, leaving a lot of unresolved technical issues. Getting through those issues has become somewhat of a career study for the artist. Currently, he’s diving deeper into Persian systems with his wife Jessika Kenney. The couple lives on Vashon Island, and both have had fruitful musical enrichment from studies with mutual friend Ustad Hossein ‘Omoumi, Kenney as a long-time student. Some of that influence, at least regarding music traditions older (yet relevant) than Western tradition, can be heard on The Narrow Garden. Opening track “Forest Sama’i,” for example, exhibits clear reference to forms of Ottoman Turkish song, and tracks “Nobis Natalis” and “Invisus Natalis” also have a sound pre-dating Western systems. Kang’s penchant for the sounds of early music moves its way into much of his work. It’s the effect of Kang’s hours and dedication into his recorded works. “The bulk of my energy is going into the internal composing life, seeing what works and what’s complete shit,” Kang says. He’s at home in the studio, glad to have the chance to listen and listen and create in that space, where technology allows a repetition in a controlled environment: “Recording then playback, it makes music possible for me ¬– to hear it.” He speaks of recording as a process of creating illusion. It’s also the place where Kang has found a chance to liberate himself and produce a prolific and particular oeuvre exploring his quest. It’s also a place most comfortable for Kang because of his sensitivity to the nuance of his instrument and of his awareness of the possibilities of sound, were they not wrestling with dominant systems. For the strings, Kang says, “One has to deal with a lot of trauma from trying to recover one’s soul from the repetition,” from the canon, from the technique, from the assumptions one makes about music or relationships of sounds. And Kang’s explicit about it: “It’s time for more radical approaches to arts, to get past the internalized oppression.” Because of systematic treatments and codification of music throughout the centuries, Kang sees that “you can’t even think of what you’re trying to think.” It’s a bit rhetorical, but it’s an important legacy of the ongoing journey in the musician’s life and exploration. The limits of a player’s language are the limits of their world. Kang wants us to hear all that’s available to us, on fretless and four-stringed instruments and even in worlds beyond music. As an arts innovator, he’s a quiet revolutionary. Kang brings ancient and multi-cultural textures to the fore in his music and documents it. Through that exploration, he’s given permission to himself, and allowed listeners and musicians to give themselves permission to never stop exploring – sounds, relationships, cultures. When you listen, this becomes evident. Maybe it’s amazing that in the centuries of music making, this kind of permission is still an innovation; it is an innovation because it must continually be renewed. Congratulations to Kang and Artist Trust on a great award. | |

| Earshot Jazz is a Seattle based nonprofit music, arts and service organization formed in 1984 to support jazz and increase awareness in the community. Earshot Jazz publishes a monthly newsletter, presents creative music and educational programs, assists jazz artists, increases listenership, complements existing services and programs, and networks with the national and international jazz community. |

Read a transcript of Joseph Stannard's conversation with composer, tubist and violinist Eyvind Kang, part of a series of exclusive interviews with collaborators and members of Sunn O))

How did you first get involved with Sunn O)))?

“Probably through [Sunn O))) engineers] Randall Dunn and Mell Dettmer, the studio that they work in, they're also good friends of mine. And we did something before with Jesse Sykes, “The Sinking Bell” on the Boris and Sunn O))) collaboration, Altar. Stephen and I had some mutual friends, but I didn't really get to know Sunn O))) until this piece came about. I went to the studio when they were recording basic tracks for Aghartha, it was kind of coincidental timing. I just happened to be there and they invited me in. I was sitting there when Attila recorded the vocals, to which we later added our own sounds. I also got to see how they work in the studio, Stephen and Greg. They were leading the process, but in their own way, y'know? They don't really tell you anything, what to do, everyone is doing their own work, but it's going through them, in a way, through their ears.”

So they're filters, in a manner of speaking?

“Yeah. I noticed that happening with Attila, definitely. He was in one world, doing his own writing, his own thing, and then they just went in there and they did it. No comment, no censorship. And later, we did that, me and Jessika and the other musicians. We kind of got involved in the piece and did our own work without much critical intervention from Stephen or Greg. They were just like, 'Do whatever you want!'”

How did you find your way into these dense, riff-orientated compositions?

“Well, let's see. What they do is just with two guitars, or guitar and bass. It is dense, but there's a lot in it that's unfolding over time, the different frequencies of the feedback coming out. Those create envelopes which are more or less dense – sometimes it's very static, sometimes it's very active. And so I started listening to those closely on the basic tracks and trying to think of a way to create an acoustic sound that could sort of emerge from those tones that emerge... so, in a way, the arrangement that I did emerges from a psychoacoustic phenomenon that emerges from them. It's three times removed, but it's just gone into the realm of acoustics, completely. Another thing is that I remember I had some interesting conversations with Stephen. He was talking about waveforms, dissonance and consonance and different types of complexity in waveforms. Knowing that he thought like that kind of grounded me into thinking about waves and vibrations rather than harmony and music theory in the traditional sense, y'know?”

Stephen characterised the process more as pure arrangement than orchestration.

“Yeah, right, right. Definitely, we wanted to avoid the feeling that there was the band accompanied by an orchestra or whatever. We talked about that. I think it would be better if you didn't realise there were other instruments going on, because when you listen to Sunn O))) in the first place, it's not like you're thinking of the instruments that they're playing. They recorded basic tracks and we overdubbed, but I guess you could say we kind of deconstructed what they had done in the first place. So it's a mirror image, in a way, created with acoustic instruments. And with the choir it's interesting because there is a mirror; I based a lot of the choir parts off of Dylan Carlson's guitar melody that he made up. I created a mirror image to that.”

“I haven't talked to him yet. Yeah, I'm really curious. By all accounts he was real enthusiastic about it.”

Presumably you've had some time with the album, to digest it?

“Yeah.”

Are you able to appreciate it objectively after having been so involved in its creation?

“I can totally listen to it from a different perspective. It's been a long time. The last thing we did was “Big Church” and that was about six months ago, maybe more. “Alice” was the first thing, and “Aghartha”... that was over a year ago. Me and Jessika were driving from LA, coming back from visiting her sister, and we listened to it on the stereo of the rental car, which was great. It was probably about a month ago, and that was the first time I really got the timing of it, the slow pacing. Yeah, we were thrilled.”

Obviously there's an element of darkness to Sunn O))). Given that you're coming from a very different, distinctly non-metal background, is this something you can appreciate about the music?

“In general, when I'm listening to something, I don't think of it as dark or light. Same thing with Monoliths & Dimensions. But then I don't listen for that, I don't have that going on in my mind. But there's definitely a transition there. I mean, the end of “Alice” is extremely uplifting, and I thought that was a new thing for them. But I dunno... maybe not, because when I listened to the basics, it sounded like that.”

Is there scope for future collaboration between yourself, Greg and Stephen?

“We've talked about doing some live collaborations in the future, but I don't know how that's going to work. I guess Stephen seems to be able to make things possible, he's just that kind of a person, I mean, just conceptually. That's how it was with this recording. At first I couldn't really conceive it, I was just trying to figure out what he was hearing. But yeah, hopefully we'll do more. I don't see why not. There's so many people involved... it's not a community but it's a mentality of like-minded people that worked on this from their own angles. I'm thinking of the engineers, the guys in Vienna, they had a lot to do with the choir parts, that was like their crew, and Stephen had some connections over there, Attila's in Budapest, y'know, then over here in Seattle they're working with a lot of different people, so I think it's like they put people into vibration.”