Melodije nuklearnog otpada milijun godina nakon što je čovječanstvo izumrlo.

streaming

Oliver Barrett’s Bleeding Heart Narrative officially called it quits in late 2012, opening the door for more work under the Petrels name. We’re a little bit greedy – we’d love to have both – but we’re overjoyed to hear this stunning follow-up to Haeligewielle. Whenever an artist records a definitive debut, one fears a sophomore slump. Fortunately, Barrett has kept fans’ hopes high with a series of singles, EPs and guest appearances. By the release of the new album, the larger question was not, “Will it be any good?” but “What kind of good will it be?” In the past two years, Barrett has explored both drone and rhythm, and while a dance album would not have been out of the question, the textured Onkalo is likely to have a deeper impact. While beats are present, they never dominate; this generous, 74-minute album is more about impression and mood.

Like Haeligewielle, Onkalo is a loose concept album, or as Barrett puts it, “a theme (with) tangents”. (Click here to read Gianmarco Del Re’s comprehensive interview for Fluid Radio.) The albums are connected by a few obvious threads: the rising volumes of “Canute” and “Giulio’s Throat” and the vocal hallmarks of “Concrete” and “On the Dark Great Sea”. Barrett’s signature sound, a blend of bowed strings and heavy keys, would make him an easy entry in a Wire blindfold test. But Onkalo is also a different beast. The percussion on the aforementioned “On the Dark Great Sea” is an early indication of evolution; the choice to close the album with a 20-minute track and an 11-minute track is another. This could have been a double disc, but there’s nothing here that needs to be removed.

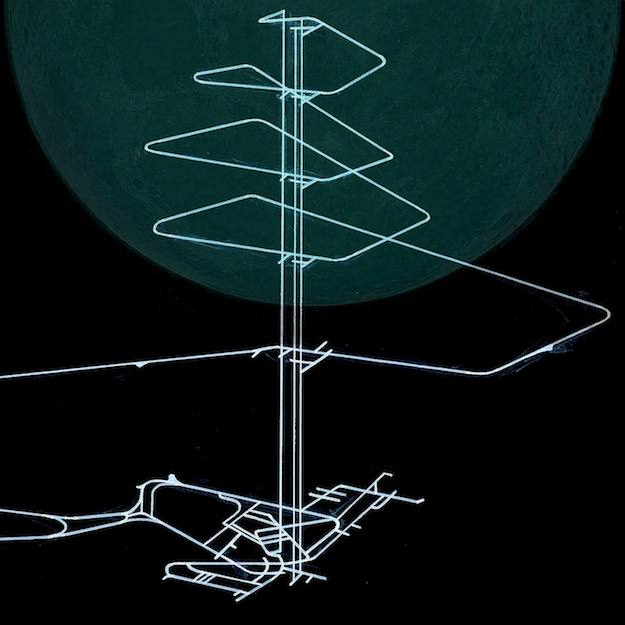

The title, which means “hiding place”, refers to a Finnish facility that is currently under construction, meant to house nuclear waste for the next hundred thousand years. The existence of such a facility leads to numerous questions, including those of legacy; when everything else has gone, humans may be known only for their garbage. This sobering thought is the album’s starting point: What endures? What is worth saving? What is humanity’s worth? As a child, Barrett used to attend protests with his parents; opener “Hinckley Point Balloon Release” honors an early experience. Musically, one begins to wonder about longevity as well. A million years from now, an alien species may retrieve Voyager’s golden record. If they can figure out the pictogram, if the record still works, a thousand ifs later, they may draw the conclusion that this is all we were. Or perhaps all that will remain of us will be ancient radio and television signals, bouncing haphazardly throughout universes.

Why do we make art, if not to make an impact or leave an impact? Barrett’s current work causes us to think, if not to act. The creation of art is itself a protest, a proclamation that humanity retains both the ability and the will to surprise. While the listening act is passive, sound can create seeds. In the same way as the earlier optimism of the space race was tempered by military applications and dull disappointments (“Where’s my jetpack?”), the stagnancy of the popular musical climate is challenged by Barrett’s original ideas: twinkles and drones, surges and decrescendos, sound and fury, signifyingsomething. Take for example the introduction of the major theme of “White and Dodger Herald the Atomic Age” at 4:37, a transformation from the spiritual to the physical. The mind yields to the heart, the action to the reaction; the train switches from one track to another.

A physicist experiences a breakthrough and puts down his pen. A construction worker realizes that he is being sickened by his work. A protester asks, “Why am I marching around, holding this sign?” A musician wonders whether his work will endure, or even matter. The fingers are lowered to the keys. The sounds flow forth. Time and space collapse. Everything is connected. - Richard Allen

The title, which means “hiding place”, refers to a Finnish facility that is currently under construction, meant to house nuclear waste for the next hundred thousand years. The existence of such a facility leads to numerous questions, including those of legacy; when everything else has gone, humans may be known only for their garbage. This sobering thought is the album’s starting point: What endures? What is worth saving? What is humanity’s worth? As a child, Barrett used to attend protests with his parents; opener “Hinckley Point Balloon Release” honors an early experience. Musically, one begins to wonder about longevity as well. A million years from now, an alien species may retrieve Voyager’s golden record. If they can figure out the pictogram, if the record still works, a thousand ifs later, they may draw the conclusion that this is all we were. Or perhaps all that will remain of us will be ancient radio and television signals, bouncing haphazardly throughout universes.

Why do we make art, if not to make an impact or leave an impact? Barrett’s current work causes us to think, if not to act. The creation of art is itself a protest, a proclamation that humanity retains both the ability and the will to surprise. While the listening act is passive, sound can create seeds. In the same way as the earlier optimism of the space race was tempered by military applications and dull disappointments (“Where’s my jetpack?”), the stagnancy of the popular musical climate is challenged by Barrett’s original ideas: twinkles and drones, surges and decrescendos, sound and fury, signifyingsomething. Take for example the introduction of the major theme of “White and Dodger Herald the Atomic Age” at 4:37, a transformation from the spiritual to the physical. The mind yields to the heart, the action to the reaction; the train switches from one track to another.

A physicist experiences a breakthrough and puts down his pen. A construction worker realizes that he is being sickened by his work. A protester asks, “Why am I marching around, holding this sign?” A musician wonders whether his work will endure, or even matter. The fingers are lowered to the keys. The sounds flow forth. Time and space collapse. Everything is connected. - Richard Allen

Onkalo, the title of Oliver Barrett's

sophomore Petrels outing, stands for ‘hiding place' and refers to a

nuclear fuel repository currently under construction in Finland designed

to house hazardous nuclear waste for a minimum of 100,000 years. That

idea serves as a conceptual starting point for the release, though it's

hardly the most pertinent thing about Barrett's Haeligewielle follow-up—more

telling is the fact that no instrumentation details are included (a

vocal credit for one track aside), a move that implies that the listener

should fixate on the sound mass on its own terms rather than be

sidetracked by who played what. Having said that, there's no denying

that the album's imaginative track titles allude to possible narratives,

some with positive overtones (“Hinkley Point Balloon Release”) and

others more ominous (“Kindertransport”). Barrett's a sound designer who

sequences blocks of variegated sounds—strings, organ, choral voices,

electronics, etc.—into multi-layered compositions of ambitious scope and

length, with two of the release's nine pieces ten minutes long and one

twenty. He's largely his own man, too, though it is impossible to ignore

the Steve Reich echo in the percussive patterns running through “Trim

Tab pt. 2.”

A sense of wonder permeates Onkalo's

opening pieces. “Hinkley Point Balloon Release” ushers in the album with

the euphoric sweep of orchestral strings, after which “Giulio's Throat”

uses crystalline elements to suggest some fantastic enchanted setting.

Darkness gradually floods in, however, as embodied in the oscillating

chords that swell until they all but obliterate the track's originating

sounds. Interesting juxtapositions surface: during “On the Dark Great

Sea,” the voices of Holly Stead and (presumably) Barrett act as a

full-bodied vocal choir whose roar is heard alongside pounding drums—the

classical and tribal conjoined. Contrasts occur between tracks, too,

with the industrial heaviness of “Characterisation Level” followed by

the strings-only “Kindertransport.” In this context, the presence of a

funky techno rhythm (as occurs within “Trim Tab pt. 1”) is a surprise

(if not a non sequitur) though not an unwelcome one.

One of the album's most powerful tracks is

the twenty-minute “Characterisation Level,” which flirts with doom metal

in the raw guitar-generated squalls that appear with crushing force.

Barrett maintains a controlling hand throughout, however, as the molten

material never turns into decimating feedback but instead undergoes a

slow metamorphosis as its guitar elements are joined by electronic

squiggles and symphonic strings pulsations. Fifteen minutes along, drums

enter, advancing the evolution from industrial to a style more akin to

rampaging krautrock.

An elegiac feel infuses some pieces, including

“Time Buries the Door,” where hurdy gurdy-like melodies flutter

plaintively amidst churning strings and percussion, and

“Kindertransport,” a beautiful and keening setting whose title,

intentional or not, evokes the image of a train packed with children

bound for a WWII concentration camp. Too often the word journey is used

to describe an album, but it's warranted in the case of Onkalo.

The listener truly does feel as if he/she starts in one place and ends

up somewhere entirely different, and the stopping points along the way

are consistently unpredictable. - textura.org

Oliver Barrett’s debut as Petrels was named Haeligewielle, an Anglo-Saxon toponym for “holy well.” Along with the press release and the song titles, this was the kind of artist’s statement for which music reviewers might wait years. “Songs of water, songs of stone” read the copy, and three of the tracks referred to William Walker MVO and his work in the Winchester Cathedral crypt which–as of 1906–was flooded and causing gradual structural failure. Over the next six years and diving alone in absolute darkness, Walker fortified the submerged crypt with concrete columns: sacred work in a personal aeligewielle. Water, stone. One erodes, one endures. Writing for Fluid Radio, Brendan Moore noted how Barrett pitted “an all-consuming darkness against the frailest slivers of light.” Richard Allen, writing for The Silent Ballet, remarked “Its characters and etymologies dance around each other like fish in a waterspout.”

Onkalo–the title of Barrett’s latest full-length Petrels album–returns us to a dark, underground construction, but the uncertainties and the chain reaction of the track titles pose a slightly trickier thematic summary, nothing like the stone/water duality of Haeligewielle. “Hinkley Point Balloon Release” refers in part to a peaceful protest of the Hinkley Point nuclear power station in Somerset, during which demonstrators released 206 balloons into the air, one for each day that had passed since the event at Fukushima. “On The Great Dark Sea” quotes the Bhagavad Gita–or at least Oppenheimer’s version of it–while “Kindertransport” shares a name with the UK’s Kristallnacht-erafoster program for over 10,000 displaced children from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The album title refers to a nuclear waste repository currently being excavated in Finland, intended to reach a bed of bentonite clay 520 meters in depth.

Barrett clarifies that these are not concept albums per se. The narrow theme is meant to improve compositional focus, eliminate any easy answers first, sort of like writing 50,000 words in English without use of the most common vowel. How else would the processed strings of Haeligewielle have punched so far higher than their weight class, transcended sythesizers so utterly? Indeed, Onkalo largely continues the sound of its predecessor, adding to the sometimes mythological proportions and, paradoxically, the reassuring claustrophobia. The music is the opposite of Planck’s constants, which are those dimensions intended to divide the microscopic from the impossibly small. Instead Onkalo divides the immeasurably large from the everyday: we hear voice, processed strings, “acoustic instruments [that] sound electronic and via versa“, and now the reverberations of orbits, for which the term epic would be an understatement. “Giulio’s Throat” opens as granular and warm–those slivers of light mentioned in Brendan Moore’s review–and gradually exceeds critical mass. “White And Dodger Herald The Atomic Age” gurgles with ions: the swishing and ricochets of real-time knob adjustments boil like heavy water, and its backdrop of horizontal analog measures is far from anachronistic. The distorted guitar ambient of “Characterisation Level” is scalding and nutrient-dense, and the drum-circle denouement is terrific (bad form, that final 60 seconds of tinnitus, which is literally the only real blemish across the album’s 74-minute span). The first half of the string-dominant “Kindertransport” offers up scents of the east, although a slightly dissonant turn at the midpoint begins a truly modern, adagio finale. For such a turbulent subject, it is an optimistic and serene parting glimpse. Post-Hiroshima tragicomedy.

Denovali will issue Onkalo in CD, double LP and digital format on March 22. Pre-order now here.

- Fred Nolan for Fluid Radio

ONKALO: INTERVIEW WITH PETRELS

As part of our Denovali Swingfest coverage we will be speaking with various artists performing at the festival in April. Gianmarco recently spent time with Petrels to discuss all manor of interesting things including the highly anticipated new album Onkalo. Also watch out for a full length review of the album in the next day or so…

You seem to favour “concept” albums. After your critically acclaimed debut solo album Haeligewielle, centred around William Walker and Winchester Cathedral, comes Onkalo (‘hiding place’) which is the name of the spent nuclear fuel repository currently under construction in Finland to house hazardous nuclear waste. How important is it for you to follow a narrative thread while developing an album?

I’m not sure if I’d categorise either album as strictly a concept one necessarily, though that might just be down to the way I think of these. I definitely find it useful to have a theme or subject matter in mind when working on music though – from a single track right through to a whole album. Certainly with each Petrels recording I’ve made I’ve tried to work around particular ideas and subject matter in an effort to place some degree of limitation around the sounds and structure and also (hopefully) give cohesion to the end result. I think the emotive or narrative aspect of making music is always right up there at the forefront of my mind when I’m writing it so defining it quite clearly from the start gives me something to refer back to throughout the process.

Haeligewielle was more tightly focused in that it was based around the work of one man in a specific time and place, and the implications of the work he was doing. With Onkalo on the other hand I’ve taken an initial subject matter (my interest in which was sparked by the incredible ‘Into Eternity’ documentary that deals with the whole Onkalo project far better than I ever could) and then gone off on much wider related tangents with what I was thinking about and reading around whilst making it. But ultimately it just comes down to finding it useful to have something that serves as both the initial inspiration and also as a sounding post throughout that I can use to make sense of the stuff I’m doing.

Once again ideas relating to time, and permanence, come to the fore. How do you translate the concept of duration in musical terms without resorting to an overload of loops, extended drones and delays? How does one get the balance right? Also, I wonder if Dr Sigmund might have something to say about your apparent fear of mortality…

Ha. I think it might be more of a fascination rather than a fear of mortality exactly (or at least no more of a fear of mortality than everybody’s ingrained OHFUCKOHFUCKIMGOINGTODIEANDTHERESNOTHINGICANDOABOUTIT feeling about it that we basically just brush under the carpet anyway). I am fascinated with ideas of immense time scales though – or even how relatively small amounts of time completely change the way we as a species see things. If we see a dead body in the street we’re naturally horrified for example but give it a few hundred years and we’ll happily take our kids around endless exhibits of dead Egyptians in glass cases at the British Museum or wherever. I think maybe we (or I anyhow) just find it hard to grasp a timeframe beyond that of an average human lifespan – certainly the idea of trying to imagine what human life will be like 100,000 years from now when we’re barely got a handle on how people were living 10,000 years in the past just seems ridiculous on one level. And yet I think the most fascinating thing I found with the Onkalo project and others like it was less about the challenges of building something like that and more about imagining what the world will be like if and when its unearthed.

As far as conveying these kind of timeframes in music goes I think people’s understanding of established musical ideas and structures etc is actually pretty sophisticated. Maybe the majority of people wouldn’t necessarily be able to articulate exactly how a song works or how emotions/ideas are conveyed in music but we have such a barrage of certain structures and ideas directed at us almost constantly through our lives through radio/film/tv/adverts etc that a certain intuitive understanding of whats going on is ingrained pretty deeply. So playing with these things is exciting as all the preliminary work has been done to some degree. If I want to use a disintegrated sample of strings or whatever, I don’t have to introduce this clean and then gradually chip away at it – as a listener you can already hear what’s going on on some level so right from the start you’ve got all the establishing shots out the way and you can go straight into the narrative. So I think to an extent I don’t even really need to worry about how to convey certain themes like time and duration etc as you can just play off the vocabulary that the listener already has.

The album opens with a track titled Hinkley Point Balloon Release which refers to the recent protest at the entrance to Hinkley Point nuclear power station in Somerset. At the tail end of last year, Peter Cusack released a double album of field recordings collected from sites which have sustained major environmental damage connecting Chernobyl with Snowdonia where the nuclear fallout still effects sheep farming today. Next to Cusack’s idea of sonic journalism there have also been the more conceptual approach of Jacob Kirkegaard with Four Rooms and Merzbow’s “activist” album Dead Zone dedicated to the anti nuclear movement. What place would you say Onkalo occupies in relation to these works?

The title of Hinkley Point Balloon Release actually refers a similar protest/s a lot longer ago. My parents used to take me and my brother and sister to lots of protests and demos like that when I was little (the photo that I used in the artwork for the album is from one of them) – CND stuff especially – so I figured it made sense to open the album with that track.

I must admit that despite being very familiar with all the above artists (Peter Cusack was actually one of my tutors when I was at uni) I’ve yet to hear any of those albums. Clearly something I should rectify. So I couldn’t comment how Onkalo sits alongside them. I guess nuclear power is something that’s increasingly been back in the news, not least since Fukushima but also the impending crisis that we all should probably be thinking about more with where we get our energy in general. I do think that the waters get muddied a little between nuclear weapons – which I’m absolutely opposed to on every level – and the merits of nuclear energy. I’d say instinctively I’m against this too but then the arguments of people like George Monbiot can be pretty persuasive. I think in broad terms it seems to me that nuclear power appears to be an attractive option because it means we don’t really have to think about our energy consumption in critical terms – its a way to keep going as we are. But clearly the potential risks are crazy and if the most sensible solution to deal with the waste is to attempt to design structures that need to last far longer than our ability to really imagine then maybe there’s a problem there. Anyhow, that’s a can of worms well beyond my capacity go over in a one-paragraph answer but if anybody wanted to hear me ramble on at length about this I probably could do.

As with Haeligewielle there’s a choral line in Onkalo as well, most notably in the track On the Dark Great Sea. This time though, the tone is darker rather than luminous and the chorus part is more peripheral. Where do you record these tracks and what function do they acquire in the albums’ overall architecture?

Initially with On The Dark Great Sea I wanted to make a kind of sister piece to ‘Concrete’ – re-using certain words and a similar technique but whereas Concrete uses a single repeated line with blocked, massed harmony to contrast with the sentiment of solitary work, with OTDGS I wanted to use a much more fragmented approach to clearly highlight this sentiment. Inevitably, as often happens though, the piece kind of took a different tangent and became something a bit different (and actually, something that I’m a lot happier with than I think I would have been with my initial idea). I like writing choral arrangements though – you can use the human voice in a way that people respond to unlike any other instrument. I think in both albums these particular tracks have maybe served as a kind of anchor for the rest – or as a cypher that throws up some of the themes and ideas of the other tracks into sharper relief. As far as recording them goes, in both cases I recorded separate takes of people singing in small groups or individually and then layered them up after to create a more massed effect. With OTDGS I wanted a more stark effect than Concrete and so in the end I only used my own voice and that of my friend Holly Stead’s for the higher parts to give the piece a greater range. I’d love one day to be able to perform these (and others) with a full choir though – something to aim for.

I am quite curious about the album’s instrumentation. Haeligewielle relied on bowed strings, bent electronics, and found percussions. With Onkalo, synthesizers seem predominant while the sound is heavily textured with a retro feel to it especially on tracks such as the monumental Characterisation Level. With Kindertransport, though, strings emerge once again, lifting the tone of the album and introducing a ray of hope. How was the album constructed?

I try to keep in mind an overall arc or narrative progression for an album while I’m working on it – just making sure that no matter how wide-ranging the sonic palette for it might be there’s still a thread that runs from one track to the next that makes sense. I think the albums I like best as albums have this kind of thread running through – otherwise essentially what you have is a collection of different tracks that run to a certain timeframe, and I think in the time in which we live you need a reason to justify putting out an album – otherwise why not release tracks individually as you write them? Roughly speaking I think I approach albums in much the same way as I used to approach making mix tapes for friends (or making mixes for friends these days) – of trying to create a narrative from a sequence of tracks no matter how disparate the sounds and approaches for each individual track might be in isolation.

As far as the instrumentation for Onkalo goes it’s actually a pretty similar balance between acoustic and electronic instruments/sounds as Haeligewielle was but I think the emphasis and treatment has changed, mainly just down to the source material and ideas I was working with. Aside from Holly’s vocals in On The Dark Great Sea, all of the parts were played and recorded by me, so its generally a case of layering. When I started on Haeligewielle one of my aims for a lot of it was to try to make the acoustic instruments sound electronic and via versa, and I think this approach has carried over into Onkalo but with this album there was probably more of a conscious decision to try and let certain instruments stand alone a little more starkly without treating them too heavily. There were a number of tracks that were left half-finished though, purely because they didn’t fit with what I was going for with this album. I suspect bits and fragments of these will probably show up eventually.

Prior to releasing Haeligewielle you hadn’t visited Whinchester’s Cathedral which was the inspiration to the album. I don’t suppose you travelled to Finland for Onkalo?

I wish I had but persistent lack of funds nixed that idea. Though actually, as much as I would love to visit Finland, I’m not sure it was too important in terms of a project like this. In the same way that with Haeligewielle I was much more interested in the work that William Walker did – and the implications of that work – than the physical results themselves, with Onkalo it was the ideas and reflections that spiralled out of the notion of such a vast undertaking as that, as much as the physical construct. Having said that, the idea of performing in a vast man-made cavern half a kilometre beneath the Earth would be pretty incredible.

After your debut album which was originally released by Tartaruga, you have now joined Denovali’s roster. How did this come about and what is your relationship with your fellow “Denovalians”?

Timo from Denovali got in touch a little while after the first run of Haeligewielle had come out on Tartaruga to suggest a re-issue (and lucky for me he persisted as the first email sat unnoticed in my spam folder for a couple of weeks). Having never released anything on vinyl before I was pretty excited and obviously Denovali’s put out some great stuff so its pleasing to be able to share a roster with some amazing artists. I was lucky enough to play at Denovali’s Swingfest event in Essen in 2011 and so met a few people there and then since then had a great tour with Samuel Jackson 5 (a rare band that you can watch play every night for 11 nights in a row and not get bored) and have played with Saffronkeira, AUN, Thisquietarmy, Blueneck, The Pirate Ship Quintet, N, and did some strings for Talvihorros so I’ve met a good percentage of the roster now! Its a nice thing to be a part of.

You will be performing at the upcoming Denovali Swingfest which you have been actively involved in organising. How will you be approaching your own live set. Also, what can you anticipate about the other sets? Any live visuals planned, for instance?

I can’t wait for Swingfest in London to be honest – so many amazing artists on the bill so I just feel excited to be on it. I’ve never seen William Basinski perform so that should be pretty special and I’m also really looking forward to catching Thomas Koner again after seeing him play an unbelievable set at Denovali’s Swingfest in Essen in 2011. Add to that James Blackshaw, Andy Stott, Fennesz and basically all the rest of the line-up and I’ve got to admit that actually playing myself has pretty much been by the by. But it’ll be great to play some of the tracks from Onkalo on a decent-sized soundsystem – I’ll most likely split my set fairly evenly between the two albums though I have a couple of other things in mind. I’m also lucky enough to have Laid Eyes doing some live visuals for it, which should be great. Basically I’ll look forward to playing early on on the Saturday and then enjoy the rest of the weekend.

- Interview by Gianmarco Del Re for Fluid Radio / Photography by Wig Worland

INTO ETERNITY

cijel ifilm:

Every day, the world over, large amounts of high-level radioactive waste created by nuclear power plants is placed in interim storage, which is vulnerable to natural disasters, man-made disasters, and to societal changes. In Finland the world’s first permanent repository is being hewn out of solid rock - a huge system of underground tunnels - that must last 100,000 years as this is how long the waste remains hazardous.

A documentary film on nuclear waste produced/ directed with the support of the Danish Film Institute, Eurimaces, Finnish Film Foundation, Nordisk Film & TV Fond, Swedish Film Institute, Avek. It's about what happens to everyday nuclear waste, the kind that comes from fueling nuclear power plants. Enter Onkalo, a nuclear waste vault being blasted out of solid bedrock in remote Finland. Once finished, filled and sealed, it's supposed to keep radioactive refuse removed from the environment for 100,000 years. But what happens if a curious archaeologist stumbles upon our 'pyramid' at its half time or before?

Haeligewielle (2011) streaming

-

Apr 2013

-

Aug 2011

-

Aug 2012

-

Mar 2012

Oliver Barrett, Yowls (2013) streaming

Originally released as a run of 50 cassettes on Econore Records in 2012 this release is 5 untreated solo cello improvisations recorded in different acoustic spaces to respond to and make use of varying natural ambience.

![[ B O L T ] / PETRELS SPLIT cover art](http://f0.bcbits.com/z/24/79/2479854866-1.jpg)

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar