Gotski bend (u bližem srodstvu s bendovima kao što su Joy Division, Bauhaus, The Cure, Siouxsie and the Banshees) koji već 30 godina objavljuje albume ali kao da namjerno želi ostati nepoznat, i u tome izvrsno uspijeva. Njihov lanjski album jednostavno je čudesan. Nova anatomija melankolije i bezuvjetne tuge.

Nešto između The Nationala, Tindersticksa i Nicka Cavea.

www.andalsothetrees.co.uk/

andalsothetrees.tripod.com/index.html

www.geocities.jp/wallpaper_dying/

aattuntangled.blogspot.com

And Also The Trees continue their recent resurgence with the release of their new studio album 'Hunter not the Hunted’.

Following their most critically acclaimed album in their illustrious 30-year career ‘(Listen For) the Rag and Bone Man;’ and inspired by recent acoustic ventures, Hunter not the Hunted reinforces And Also The Trees’ as masters of atmosphere, melody and drama.

Following their most critically acclaimed album in their illustrious 30-year career ‘(Listen For) the Rag and Bone Man;’ and inspired by recent acoustic ventures, Hunter not the Hunted reinforces And Also The Trees’ as masters of atmosphere, melody and drama.

Recorded in the heart of England and a dilapidated house in France during an uncharacteristically cold summer, Hunter not the Hunted evokes a kaleidoscope of characters and scenes. And Also The Trees have always painted pictures with their music and lyrics, Hunter not the Hunted takes this to a new level. Singer and lyricist Simon Huw Jones creates protagonists rooted in their environment, be it by the sea, deep in the countryside or lost in an edgier urban setting. Guitarist Justin Jones illustrates his stories with delicate and intricate arrangements, developing his influential and distinctive orchestral-style guitar sound with flair and imagination – the guitar as raconteur - embracing influences from England, through Europe and on to the Mediterranean.

Demanding full attention from the listener, Hunter not the Hunted promises to take you to a timeless yet oddly familiar place, just beyond memory. Lyrically, Simon Huw Jones has never been better. His words hint of illicit and unsettling journeys mirrored by solitary walks along flooded landscapes drenched in light - his voice conveying emotions that permeate and resonate with each telling; sometimes soaring, sometimes deadpan. Emer Brizzolara on dulcimer provides shimmering accompaniment, with drums, double bass and percussion used to great effect to illustrate the isolation.

And Also The Trees present ‘Hunter not the Hunted’ as an entire ‘novel’ of an album. The album’s subtle shadowed beauty and intense quality are a result of recent intimate live shows in bizarre spaces, where the proximity of the audience enveloping the band, created a unique and magical feel reflected in this work. Hunter not the Hunted breathes and pulsates with its own pace. Essentially original, complex yet sparse, this is an album greedy for a contemplative audience whose likes could bring to mind the works of Mark Hollis, Leonard Cohen, Scott Walker, Marc Ribot or Patrick Watson. - www.greyzone-concerts.de/

Hunter not the hunted |  Driftwood |  When the rains come |  The rag and bone man | ||||

| CDs continued | |||||||

|  |  |  | ||||

| Further from the truth | Nailed EP | Silver Soul | Angelfish | ||||

|  |  |  | ||||

| The Klaxon | Green is the sea | Farewell to the shade | Millpond Years | ||||

|  |  |  | ||||

| Virus Meadow | And also the trees | ||||||

AND ALSO THE TREES

AND ALSO THE TREES(LISTEN FOR ) THE RAG AND BONE MAN

AATT

The little buggers have done it again! After the relaxed eerie brilliance of the ‘Further From The Truth’ albums comes something similar in tone, but of a weirder bent. They’ve lost Steven Burrows, replaced by Ian Jenkins, with piano from Emer Brizzolara, and have almost upped the old picturesque element, as the title suggests. The ominous qualities are darker and hotter, the more measured are dreamier, and the end result is remarkable.

‘Domed’ is eddying softly behind still vocals which have a steady but swiftly nagging rhythm as strings saw and keyboards twinkle, the tone doomier but bewitching, drawing you in easily, steadily closer, wondering what the Hell is happening and then it starts to simmer with some scrubby guitar, boiling over briefly with punitive drums and steadily sluiced keyboard and guitar froth, before it is snuffed sharply out. A fine start.

‘The Beautiful Silence’ is one of their cutely observed landscape songs, spinning a pertly detailed vision of some house he’s wandered into, like a leisurely thief, studying a snapshot of life before him, delightfully light guitar sliding around steady percussive guidelines. ‘Rive Droite’ is twitchier, luminous guitar peeking over the double bass and capering, shuffling drums, brushed with dexterity. Lyrics of being transported to a house, a chapel, family, a bit like Nick Cave (in tune) bathed in sunshine, and gradually enveloped in a viscous, fluid musical power. Amazing, really, how they’re able to invest something so dignified with such heat.

In ‘Mary Of The Woods’ it’s crouched again as he sings of watching kites and washing lines (obviously no x-box in his gaff), lost in emotional reverie. There’s a quaintness here too, as he walks to the parson’s house, meeting a cooper and a priest along the way. I have that problem. It snaps shut alarmingly, and a doleful, twanging ‘The Way The Land Lies’ rushes onwards, with a returning protagonist surveying a place he once loved, the guitar beckoning coyly beneath the sturdy detail.

‘The Legend Of Mucklow’ is superb, and blessed by disturbing percussion, with horrible imagery (‘Waist high in the wild oats, Goose-grass burns on his old coat, A knife tears through his throat’) and the urgent cries make little sense, adding to the awful tension of a strange but compelling piece. ‘Untitled’ is just a tasty instrumental morsel, leading to ‘Candace’ which rolls along with pictures of a wayward sister, into ‘Stay Away From The Accordion Girl’, which is always wise advice; an almost punky bass rumbling alongside the winsome guitar and a harmonious, elegant wash.

Blimey, in ‘The Saracen’s Head’ he’s off down the pub. Seriously. Being led by a little girl, apparently, in the rain. Watch out for the chavs, they know an easy target when they see one, although I’m sure they don't have such creatures in this world. In this world people travel by penny-farthing bicycle, which plays merry Hell with tour itineraries. Due for a gig in Cologne and they’re still somewhere by a Belgian river, eating sandwiches. I don’t know! ‘On This Day’ is another heavenly instrumental, just as moody as the songs, simply minus lyrics. ‘A Man With A Drum’ is a curious and superbly searing thing, lolloping along, sparkling brightly about some weirdo banging a drum in the street, although it wouldn’t surprise me if that’s their idea of an audition (‘Drummer required, with a steadfast Proustain allegiance, and knowledge of hopscotch. No flibbertigibbets.’). ‘Under The Stars’ crawls along, more fleeting glimpses of people in diverse and appealing settings in semi-sadness and luscious sounds. Of course they also throw in a fat man shaving, a milkfloat, starlings swooping and we find we’ve ended on an optimistic note, which is lovely.

Another stunner from them then, and enticingly weird, as though Wim Wenders was brought up in the Midlands.- Mick Mercer

MELODY AND MELANCHOLY

Image: And Also The Trees

In an appreciation of Worcestershire goths, And Also The Trees, Eugene Thacker digs the 'unconditional sadness' which connects their music to a melancholy continnuum stretching back to the 17th century

1.

As a student I was convinced I knew goth – it was Joy Division, Bauhaus, The Cure, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and so on. That was until I heard And Also The Trees – by accident really, walking into my friend's room one late afternoon. What I heard was a lush, almost baroque sound made up of an eerie, swirling, mandolin-like guitar, breathy and sorrowful vocals, all punctuated by a tight rhythm section that managed to somehow move through the thick, shimmering chaos. The lyrics were reminiscent of Romantic poetry, evoking a haunting narrative of rural decay and lost landscapes. The song was 'Shaletown', from the album The Millpond Years, by a band I'd never heard of before. Looking at the CD, I saw that the band photos were right in line with the sound – skinny young lads looking like they had stepped right out of the 19th century, waistcoats and all, standing in front of the ruins of some estate, full of ennui and extremely world weary. Even their name – And Also The Trees – sounded like a line from a poem. Okay, now this is gothic, I thought. Not the gothic of carnival make up, frumpy black clothes, quirky pop jingles, and sprayed-out hair. Instead, this band seemed to refuse the entire modern world; they seemed to live in ruins and brooding melancholy. And they seemed to be enjoying it. It was strangely inspirational; it made you want to feel sad too, but not for any particular reason. This was a sadness hovering between a withering past and a refusal of the present. Their exhaustion and their sadness seemed unconditional. Their romanticism was unapologetic. ‘They look like they take themselves too seriously’, someone else in the room said. ‘Exactly...’ I replied, ‘that’s what’s so great about them...’

My reason for writing about And Also The Trees (hereafter AATT) is twofold. The first reason is, quite simply, as an appreciation. AATT is one of the few bands I still listen to to this day. Their career spans some 30 years, from their initial formation in 1979 in a Worcestershire village, to their most recent album, Hunter Not The Hunted (2012). They are one of those bands who has never stopped making music and evolving, all the while retaining that melancholic thread that is evident in all their songs. All the while, AATT have remained under the radar; for them there are no number one hits, no top ten albums, no reunion tours (I like to think they prefer it this way, though age teaches us to discover inspiration in resignation).

The second reason is to try to draw out some of the themes in AATT, which for me centre around the idea of melancholy and its relationship to melody, song and lyric. One of AATT’s gifts is to find different ways of allowing melancholy to shape, form and deform melody – often to the point where a song becomes so infused with this unconditional sadness that it must either take flight into a reverberant sky or huddle itself acoustically into a hushed world of delicate timbres and half-sung syllables. For me, listening to AATT ultimately takes us back into literary history, from the 17th century ‘cult of melancholia’ to the ‘dark romanticism’ of the 18th century.i Much of this material is completely forgotten today, or only occasionally taught to listless English majors as part of tedious literary surveys. But much of it is quite relevant, especially as we struggle to comprehend the uncanny, unhuman world in which we are embedded, and which seems continually occluded from our understanding. In the poetry of the Graveyard School, for instance, one can already detect a view of the world as irremediably unhuman, full of strange weather and shifting climates, ruins that seem to be full of promise and vitality, and memories that wither with the same certainty as the surrounding landscape. That consciousness was readily apparent to those poets writing in the 18th and 19th centuries, and I think the insight of AATT’s music is to have extended this awareness to our present day.

2.

This attentiveness to melancholy in all its forms is what makes AATT stand out from their post-punk and gothic contemporaries. Typically, when it comes to music the gothic is understood either as a genre or a style, either as musical form or subcultural content, gloomy synths or tattered black lace dresses. This is all fine, but AATT are unique in that they understand the gothic in its literary context, in which the gothic is centrally concerned with an affective relation to mortality, finitude and temporality, a relation that can be described as melancholic. I would argue that melancholy – the kind of ‘unconditional sadness’ found in bands like AATT – this melancholy finds its fullest historical expression in the gothic sensibility of the 18th century, and particularly in the so-called Graveyard School of poetry of the period.

In literary history, ‘gothic’ as a term has had a wide range of uses.ii It usually refers to a type of fiction writing popular during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, of which Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764), Anne Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), and Matthew Lewis' The Monk(1796) are oft-cited examples. Many elements of the gothic novel have become the stuff of modern horror films – labyrinthine castles, gloomy cemeteries, tempestuous storms and dreaded hauntings. The gothic novel also typically contained a veritable litany of transgressive themes, from madness and suicide to sorcery and demonism. It was perhaps because of this that gothic novels were both critically disparaged and immensely popular.

However, the gothic novel drew heavily on the poetry of the preceding generation, and in particular on a loose grouping of poets that have come to be known as the Graveyard School. Historically the vogue for graveyard poetry was brief, exemplified by poems such as Thomas Parnell's ‘Night-Piece on Death’ (1721), Robert Blair's ‘The Grave’ (1743), Thomas Gray's ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ (1751), and Edward Young's epic The Complaint; or Night Thoughts on Life, Death, and Immortality(1742). Because the setting of the poems tended to be among tombs, ruins and wintry landscapes, the name was given, and seems to have stuck. Reading the poems today can be difficult – not only because no one seems to read poetry these days, but also because many of the motifs have become the clichés of the horror genre and what we often think of as ‘goth’. But the Graveyard School is also part of a larger discourse in the 18th and early 19th century around the role of the aesthetic, particularly in the face of scientific progress, emerging industrialism, and an ongoing crisis in traditional religion.

Image: Gwenda Morgan, wood engraving for Gray's 'Elegy written in a Country Churchyard', Golden Cockerel Press, 1946

What both the gothic novel and the graveyard poets have in common is an ambivalence towards the legacy of the Enlightenment. I say ‘ambivalence’ here because critics of the period were perpetually divided on the value and relevance of the gothic sensibility. For some, the graveyard poets and gothic novelists signaled nothing less than an all-out critique of the over-reliance on human reason and the proprietary interiority of the individual, humanist subject, a critique launched through an aesthetics of excess and transgression. For others, the plethora of gloomy meditations on death and the supernatural were really ways of grappling with and even affirming religious experience outside of traditional religion; the terrors were there simply to teach, smuggling in religion through the back door. The truth probably lies somewhere inbetween; while such poems and novels do evoke a sense of an absolute and unhuman dread, often this is resolved through a chivalric code of righted wrongs (villains ousted, victims saved), or through the philosophical fiat of reason (illusions revealed, order restored).iii

Whether these works were essentially progressive or conservative is a debate that preoccupies scholars to this day. What many agreed on, however, was that the key to the gothic sensibility lay in the way that aesthetic form – and hence aesthetic experience – was constantly undermined by an affective content that remained continually in excess of it. Against the neoclassical emphasis on form, the gothic ululation of the formless; against the aesthetic obligation towards a unified whole, the gothic predilection towards the incomplete and fragmentary; against the neoclassical adherence to boundaries, the gothic fascination with transgression.

It is one thing to make claims of efficacy for a literary work – that it does this or it does that, that it is critical or that it undermines, that it reveals or illuminates, that it succeeds in communicating what cannot be put into words. But what is one to do with, for instance, a poem so weighed down in its affective content that it crumbles in on itself?

Flow, my tears, fall from your springs!

Exiled for ever, let me mourn;

Where night's black bird her sad infamy sings,

There let me live forlorn.iv

These lines are from the opening of John Dowland's poem ‘Flow My Tears’ (1596), and they express neither the constraint of later neoclassical aesthetics nor the exuberant adventure of the chivalric-gothic style. They express a sadness that seems without cause and without resolve; a melancholy that is almost depersonalised, seeping into the very environment.

Such a sadness has a rich cultural history, from its association with the bodily humors in Greek medicine, to the brooding tragic figures of Elizabethan drama. Against the backdrop of religious conservatism, melancholy during the Reformation blossomed into a fully-fledged ‘cult of melancholia’,and sentiments like those of Dowland's poem found their religious analogue in Thomas Browne:

Oblivion is not to be hired: The greater part must be content to be as through they had not been...The number of dead long exceedeth all that shall live...Every hour adds unto that current Arithmetique which scarce stands one moment...Since our longest sunne sets at right descensions, and makes but winter arches, and therefore it cannot be long before we lie down in darknesse, and have our light in ashes.v

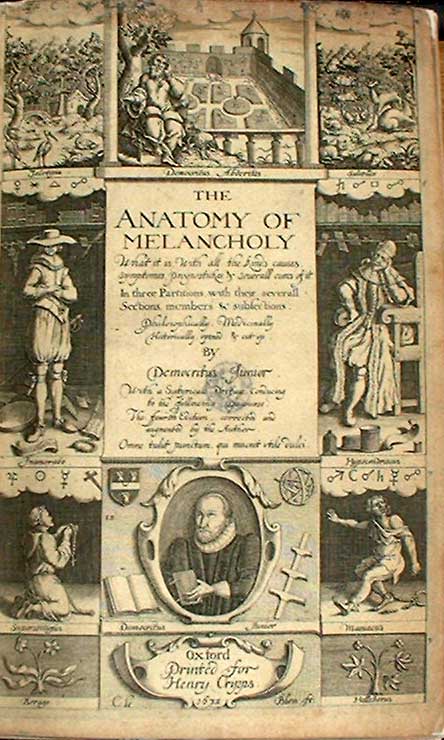

Robert Burton, whose The Anatomy of Melancholy has remained a reference on the topic to this day, noted the ambivalence of melancholy when he referred to it not simply as sadness, but as a ‘pleasurable sadness.’vi

Image: Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1621

It was this troubling aspect of melancholy – the way it continually threatened aesthetic form, consuming a text and causing it to crumble from within – it was this aspect that 18th century poets inherited. Melancholy was, for Enlightenment science, a strange condition – it was a despondency from which one has little or no desire to escape; it seemed to have all the contours of religious experience, except that it expressed a disenchantment with traditional religion; it seemed to be highly sensitive to external conditions and yet no real cause for it could be found, let alone a ‘cure’. The problem was ramified by the popularity of melancholy in the poetry, prose and drama of the period. If melancholy was a cultural and even a medical problem, then to write melancholic poetry was simply adding fuel to the fire. What Joseph Addison, writing in the Spectator, famously called ‘the Fairie way of Writing' threatened to unmoor the self from the world, and to blur the distinction between the real and the imagined, the boundary between reason and faith that constituted the underpinning of enlightenment philosophy.

On the one side the detractors of melancholy tended to view it as a medical condition, resulting in overwrought and uninspired poetry; on the other, the proponents of melancholy wanted to align it with the poetic imagination, making claims for its ability to raise the reader to almost religious heights. What both sides missed however, was the way in which melancholy tended to be characterised as an inner mental or psychological state – a feeling interior to a subject who would then externalise this feeling through poetic expression. But a survey of the poetry during the period shows a different picture. It shows poets who, while they do play into the stereotype of the poet-as-expressive-subject, also allow for the unhuman, impersonal world to seep through. James Thomson's poem ‘Winter’ (1726) provides one example of this turning-away from the human world:

Low, the WoodsBow their hoar Head; and, ere the languid SunFaint from the West emits his Evening-Ray,Earth's universal Face, deep-hid, and chill,Is one wild dazzling Waste, that buries wideThe Works of Man.vii

This is not simply a shift towards nature-poetry, many of the graveyard poems rigorously refuse naturalistic realism in favor of specters and hauntings, and neither is it a glorification of nature as seen in and through the human subject – a hallmark of British Romantic poetry. Instead, the graveyard poets invert this model of the expressive subject, allowing the self to dissipate and disperse into the anonymity of the world, rather than acting as a super-charged channel for ‘Nature.’viii Many of the techniques are familiar – allegory, metaphor, personification – but the results are different, they are tragic rather than heroic. The graveyard poets sing the unhuman, they even sing the unhuman of the human, and this constitutes their melancholia.

This transformation of the human into the unhuman is seen in Thomas Wharton's The Pleasures of Melancholy (1747). Wharton begins with the requisite evocation of the Muses, though his are of a darker sort:

O lead me, queen sublime, to solemn gloomsCongenial with my soul; to cheerless shades,To ruin'd seats, to twilight cells and bow'rs,Where thoughtful Melancholy loves to muse... .ix

But the poem quickly moves from a depiction of melancholy as the inner thoughts of a subject, to melancholy as something akin to an impersonal, inorganic force, pulling the subject into the nocturnal environment around it:

While sullen sacred silence reigns around,Save the lone screech-owl's notes, who builds his bow'rAmid the mould'ring caverns dark and damp,Or the calm breeze, that rustles in the leavesOf flaunting ivy, that with mantle greenInvests some wasted tow'r.x

Wharton's poem not only evokes a melancholy of mortality and finitude, but it also shows us a strange vitalistic melancholy, encapsulated in the fruiting mold of the caves and the ivy overflowing the tower ruins. Everything – including the corpse, including the living body of the poet – everything becomes imbued with this impersonal sadness. This is literary personification, but in reverse.xi David Mallet's poem 'The Excursion' is emblematic of this kind of impersonal personification:

Night hears from where, wide-hovering in mid-sky,She rules the sable hour: and calls her trainOf visionary fears; the shrouded ghost,The dream distressful, and th'incumbent hag,That rise to Fancy's eye in horrid forms,While Reason slumbering lies.xii

Mallet, like many of poets of the supernatural, deals with the commonly found motifs of night, darkness, the tomb and spectral beings. In poems like these, melancholy is found everywhere, not simply in the brooding, depressed brain of the human subject writing the lines of poetry. Melancholy is environmental, melancholy is climatological, it is at once the night sky and the slow moving seconds of twilight, and it also infuses the spectral domain of fears and dreams, ghosts and demonic shapes – and the blurred line between them. In Mallet's poem, for instance, it is not always clear if we really are in the domain of the supernatural, or if the spectral and creaturely shapes are merely figments of an overactive imagination. And in a way it doesn't matter, since much of the poetry of this type relies on this confusion – at once horrific and pleasurable – between what is thought and what thinks through us. In the poetry of the supernatural, melancholia makes possible this pleasurable confusion.

This confusion – which Edmund Burke associated with the sublime – reaches a pitch in Robert Blair's poem ‘The Grave’, a poem that contains some of the most grotesque and ‘gothic’ imagery of the period:

Ah! how darkThy long-extended realms, and rueful wastes,Where nought but silence reigns, and night, dark night,Dark as was chaos ere the infant sunWas roll'd together, or had tried his beamsBy glimm'ring through thy low-brow'd misty vaults,Furr'd round with mouldy damps and ropy slime,Lets fall a supernumerary horror...xiii

I've always been fascinated by Blair's almost awkward phrase ‘supernumerary horror’, but it makes a certain sense within this impersonal and chaotic world of mould, stone and slime. It is almost as if graveyard poetry allegorically performs the process of the corpse's decay, an awareness of the inorganic world within our very own living bodies. Blair's obsessive interest in the details of the sepulchr are more than merely the products of a morbid imagination; they serve to emphasise the impersonal materiality to which corpse, mist and stone are ultimately all subject.

3.

This little detour into literary history is simply meant to suggest that there is another tradition of melancholy aside from that of the possessive and expressive individual of Romanticism.xiv That other tradition deals with a mood – ‘mood’ both in the usual sense of a state of mind or feeling, but also ‘mood’ in the environmental, ambient sense, mood as an impersonal, affective space. As such, this mood need not simply be the subjective expression of a depressed individual, but something that is more and less than the subjective individual, a mood that precedes and exceeds the subject.xv And it is this ‘mood’ that we can call melancholy. Melancholy in this sense is, first and foremost, unconditional. It is not the result of particular conditions or a reaction to particular events (there's plenty of this to go around, to be sure...). The sadness of melancholy is without cause or resolve; it is not just an expression of a personal sadness, but an impersonal sadness, a melancholy that is inseparable from the physical (and metaphysical) world – a sadness of the world.

This is the type of melancholy that I find evocative in a band like And Also The Trees. No band likes to be put into a box, and it's a mistake to simply label AATT as ‘goth’ since both their music and the goth subculture have drastically changed over time. But if AATT's music is gothic this is because they understand the term in its literary and poetic sense, as an anonymous melancholy, as an unconditional sadness. And it is a thread that is evident, though in different guises, in each of AATT's albums.xvi In their early works AATT map out a kind of melancholic, post-punk sound through instrumental sparseness and haunting lyrics, calling to mind Joy Division, Gang of Four, and Killing Joke (best exemplified by their inimitable song ‘Slow Pulse Boy’; one song from a demo tape contains the line ‘Green is the sea / And also the trees’).xvii Melancholy exudes from these albums by virtue of their subtractive quality, shards of sentences, fragments of melodies, rhythms that hit the ground running and then come full stop.

This shifts during the late 1980s and early 1990s, as AATT adopt a more lush, baroque sound, characterised by guitarist Justin Jones' reverberant, mandolin-like guitar, and vocalist Simon Huw Jones' fuller, almost breathless vocals. The lyrics in albums like The Millpond Years (1987) andFarewell to the Shade (1989) often evoke despondent, rural landscapes, and the almost archetypal figures lurking within them.xviii In the 1990s AATT's sound shifted again, this time away from the aesthetic of 19th century Romanticism and its evocations of ghostly, rural landscapes and towards an urban melancholy, producing albums that called to mind film noir, Bernard Hermann and Nick Cave. The sound is more raw, resulting in a kind of industrial crooning against a backdrop of fuzz and electricity. And, at the turn of the millennium AATT shifted yet again, with a more intimate sound, bringing in elements of jazz and chamber music with new instrumentation (evidenced in 2003's Further From The Truth and (Listen for) the Rag and Bone Man from 2007, the former of which contains the elegiac ‘Feeling Fine’). This emphasis on intimacy and solitude has recently been complimented by two acoustic albums, When The Rains Come (2009) and Driftwood (2011), both of which feature unplugged renditions of early AATT songs.xix

In his lyrics, Simon Huw Jones pays homage to the tradition of the gothic sensibility in poetry and its ability to glean emotional insights from seemingly innocuous details and everyday gestures (in one song Jones sings ‘His box of birds / Weighs him down / As he walks / Far from this town’; in another ‘Far from the lantern swaying / Summer dusk, your seaweed breath / Screams brine out of the bay’; and in another ‘Cathedral quiet and narcotic seas / In a mind of tide-mark memories...’). At times his lyrics turn to narrative, constructing impressionistic scenarios of mythical characters, objects and scenery, culled from a bowl of rotting fruit, a hand on the shoulder, the slow meandering sunlight across the walls.xx At other times the lyrics evoke unpopulated spaces, broken landscapes and empty rooms, filled only by dusty memories and a kind of wayward, delirious nostalgia.xxi All of this is complemented by the music, much of which is characterised by Justin Jones' guitar, be it the shimmering swaying of songs like ‘Mermen of the Lea’ and ‘L'Unica Strada’, the skeletal lyricism of ‘Sickness Divine’ and ‘Feeling Fine’, or the plaintiff and elegiac sound on the acoustic albums.

The most recent AATT album, Hunter Not the Hunted (2012) is a kind of summation of the band's ongoing musical reflection on melancholy.xxii The song I've been listening to over and over is ‘My Face is Here in the Wildfire’. For me it represents one of the most distilled expressions of what AATT are all about. It also whittles the song structure down to two basic elements, voice and guitar, word and melody, the lyric and the lyrical (returning to the ancient Greek notion of a song rendered to the accompaniment of a lyre). The lyrics themselves are abstract, an almost surrealist juxtaposition of an impersonal, anonymous face melding perfectly into the natural world: ‘My face is here in the maelstrom / My fossil bones jutting out into the night air / And the insects, sacred / Whirling through my green black life-riddled hair’. On paper the lyrics read like poetry – but it's still the written word. When sung, the words take on a new form – they are almost emptied of semantic content and themselves become lyrical form. For instance, when Jones sings the line ‘I can hear the rooks in their light sleep crow’ the last three words are spaced out – ‘light....sleep...crow’ – so that they become detached from the grammar of the sentence, almost stochastically released, like rain drops on a window when it begins to rain.

In moments like these AATT take up lyrical form and in essence weigh it down with melancholy, so much that the words break apart, becoming so many scattered remains, strangely tranquil in their non-human habitat. This is not a lyricism of an expressive, emotional subject, but a lyricism turned outwards into the world, a kind of inverted lyricism, weighed down and rendered inorganic through this special type of melancholy. And it is this that I find resonant with the tradition of the gothic and graveyard poetry. A band like AATT takes up graveyard poetry's turn towards melancholy as a unconditional sadness, and in so doing they produce something that is actually an inversion of the traditional notion of lyric, in the sense of a poem uttered by a single speaker, and expressing a state of mind or feeling that is constitutive of that individual subject. Lyric is, in this traditional sense, interiority and solitude. Instead, AATT, like the graveyard poets, offers the exteriority of a world that persists in spite of us, but also an exteriority that we discover is always within us. Likewise, the solitude of these melancholic songs is not the solitude of the individual or even of the lonely crowd, but the solitude of the world, glimpsed in the numerous pauses of silence on which the graveyard poets endlessly dwell. What results is a lyricism of the impersonal, of climate, cloud, moss, river, stone and ruins.

Footnotes

iThanks to Josephine Berry Slater and Mira Mattar for their helpful comments on this article.

The term 'dark romanticism' is used by G.R. Thompson in his anthology The Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism (Washington State University Press, 1974). Thompson uses the term to describe British poetry and prose in the period between Enlightenment neoclassicism and the emergence of Romanticism, and which is inclusive of both the Graveyard School of poets and the gothic novelists.

ii Innumerable student theses and scholarly books have been written on the literary gothic, and I will not attempt to summarise them here. Contemporary surveys include David Punter and Glennis Byron'sThe Gothic (Blackwell, 2004) and The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Literature, ed. Jerrod Hogle (Routledge, 2002). Earlier critical works that are still interesting include Montague Summers' The Gothic Quest – A History of the Gothic Novel and Mario Ppraz's famous study The Romantic Agony. From a perspective of cultural theory, see Fred Botting's many writings on the gothic, such as Limits of Terror: Technology, Bodies, Gothic (Manchester University Press, 2010).

iii One of the few voices to speak on behalf of the gothic sensibility was Richard Hurd, literary critic and bishop of Worcester. Hurd's Letters on Chivalry and Romance (1762) appeals not to the contemporary literature of his time, but to the earlier examples of Shakespeare, Ariosto and Milton. Against the neoclassical emphasis on form, symmetry and balance, Hurd argued for the influence of a medieval gothic sensibility characterised by more vigorous, chivalric codes of honor, adventure and a religious temperament. Hurd is conclusive in his analysis: '...you will find that the manner they paint, and the superstitions they adopt, are the more poetical for being Gothic.'

iv John Dowland, 'Flow My Tears', in The Lute Songs of John Dowland, ed. David Nadal (Dover, 1997), p. 58.

v Sir Thomas Browne, 'Urne Buriall; or, a Discourse of the Sephulchrall Urnes Lately Found in Norfolk', in The Religio Medici and Other Writings (J.M. Dent & Sons, 1945), p.135.

vi Though Burton's massive tome was ostensibly presented as a medical textbook – meaning that he, like the Hippocratic authors, viewed melancholy as a disease – much of it is a compendium of the different views on melancholy in literature, art and the sciences. Nevertheless, the title alone of the 1621 edition is enough to make one a little depressed: The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up.

vii James Thomson, 'From The Seasons', in English Romantic Poetry and Prose, ed. Russell Noyes (Oxford University Press, 1956), p. 5.

viii While many of the key works of the Graveyard School pre-date the mainstream of British Romantic poetry, I would argue that this inversion of the subject continues, less as a 'school' and more as a tendency, even within Romanticism – for instance, in Bryon's poem 'Darkness', Shelley's 'To Night', and Keats' poems 'Ode to Melancholy' and 'After Dark Vapours.'

ix Thomas Warton, 'From The Pleasures of Melancholy', in English Romantic Poetry and Prose, ed. Russell Noyes (Oxford University Press, 1956), p.61.

x Ibid.

xi This idea of depersonification invites a comparison with the notion of pathetic fallacy in literary criticism, especially as laid out by Romantic era critics like John Ruskin. Whereas pathetic fallacy may involve the attribution of human qualities to non-human things (or, as a variation, the attribution of animate qualities to inanimate things), I'm pushing here for an inversion, in which the human is discovered to be non-human, and so-called human affects such as melancholy are presented as properties of the world as such. Of course, in these sorts of discussions one never really gets away from the most basic fallacy, which is that it is ultimately human beings that make a claim at all, one way or another.

xii David Mallet, 'The Excursion', in The Works of the English Poets, from Chaucer to Cowper, ed. Alexander Chalmers (J. Johnson et al., 1810), vol. XIV, p. 17.

xiii Robert Blair, 'The Grave', in English Romantic Poetry and Prose, ed. Russell Noyes (Oxford University Press, 1956), p.23.

xiv This is unfair, I know, since much of Coleridge and Wordsworth can be profitably read in this way (Blake is another case altogether). The problem is that the figure of the poet is often so over-determined in Romanticism that it occludes the myriad, non-human elements at play in their work; the graveyard poets happened upon their poetry, whereas the Romantics felt destined to write their poetry. For a counterargument, see Ron Broglio's book Technologies of the Picturesque (Bucknell University Press, 2008).

xv In a way, the ancient Greeks already intuited this. The texts in the Hippocratic Corpus talk aboutmelancholia as a condition at once psychological and physical – as an imbalance in the bodily humors, a sense of being overwhelmed by 'sadness, fears, and despondencies' caused by an excess of black bile. For Greek medicine (and philosophy) balance was everything. If the substances of the body tipped to one side or the other – through diet, lifestyle, or simply obtrusive thoughts – then the result could be a form of sadness beyond respite.

xvi AATT were, for many years, a quartet, comprised of brothers Simon Huw Jones (vocals) and Justin Jones (guitar), with Steven Burrows (bass) and Nick Havas (drums). In recent years the AATT sound has been filled out by the addition of Ian Jenkins' wonderfully thick double bass playing, Paul Hill's delicate jazz drumming and Emer Brizzolara's precision on dulcimer and harmonium.

xvii Their 1983 debut And Also The Trees (produced by The Cure's Lol Tolhurst and which crashes in with the track 'So This is Silence') and their follow up Virus Meadow crystallises this combination of musical sparseness and stark, impressionistic lyrics. For me, AATT's debut album stands right alongside Bauhaus' In The Flat Field, The Cure's Seventeen Seconds, and Siouxsie and the Banshees' Spellbound as a classic of the post-punk, early goth sound.

xviii The opulent soundscapes of albums like these, along with Green is the Sea (1990) look askance to the mid to late ’80s sounds of The Cure, Siouxsie, and many of the 4AD projects, while also bringing in 'neoclassical' elements found in many darkwave bands associated with the Projekt label.

xix One can only appreciate these by comparison with their originals, as with the songs 'A Room Lives in Lucy' and 'Dialogue' – I long to hear acoustic versions of 'Slow Pulse Boy' and 'The Ship in Trouble'...

xx Cf. the songs 'Vincent Craine', 'Wooden Leg', 'The Legend of Mucklow'.

xxi Cf. 'Gone...Like the Swallows', 'The Street Organ', 'Mary of the Woods'.

xxii Songs such as 'Only', with its Spanish sounding guitar and rich textures of voice, dulcimer, and percussion, have all the drama of earlier albums like The Millpond Years, but it is a more muted drama that gradually contacts and expands, much like the expansive reverberations of Simon Huw Jones' trademark vocal style. Some songs, such as 'Burn Down This Town' look back to the lulling, waltz-like melodies of Green is the Sea, while 'Hunter Not the Hunted' adopts a more chamber music approach in its pared down instrumentation.

From a rural village in Worcestershire, England, brothers Simon(vocals) and Justin Jones (guitar) formed And Also the Trees in 1979 with bassist Steven Burrows and drummer Nick Havas. In response to an ad by the Cure looking for support bands on their English tour, the Jones brothers sent a tape and ended up doing several dates and later an entire tour with Robert Smith and co. in 1981. And Also the Treesstill hadn't released any material at that point, so the Cure's Lol Tolhurst produced a single ("Shantell") and the band's eponymous debut album, released in February of 1984. Tolhurst's work made the Cure an easy pointer for And Also the Trees' sound, though the fragile beauty of Joy Division and the Chameleons also lend comparisons. The band contributed a session toJohn Peel's BBC radio show, and Continental critics lavished praise on subsequent albums Virus Meadow(1986), The Millpond Years (1988) and the live LP The Evening of the 24th (released 1987). The notoriously fickle U.K. music press, however, deserted the waning Goth fad and the group was left drifting. Farewell to the Shade, released in 1989, was And Also the Trees' final British release, as well as the only album available in America (on Troy Records). The group moved to the German label Normal for 1992's Green Is the Sea and The Klaxon, released the following year. - allmusic.com

An exclusive interview with

Simon Huw Jones

from

AND ALSO THE TREES

Sometimes I think that it’s a miracle a group like And Also the Trees exists and keeps coming up with such delicate and fine romantic music. Every release has individuality, depth and a unique supernatural element. Doesn’t everyday life and its un-poetic aspect, affect your songwriting? Don’t any happy moments find the way to become songs?

Simon Huw Jones: First, thank you for the compliment in the question, but if you can’t hear any joy or happiness in our music we have failed you. There has to be light in the darkness. And everyday life is in there too – a fat man shaving, a girl standing in a garden, walking to a pub in the rain, the smell of fried fish and beer, answering the telephone – it’s notthat poetic is it?. We try to create a balance… these are the final words from the second song on the album, I think they sum up what I’m trying to say – “I came upon a house, somewhere I’d never been before, and in this place of light and dark I feel my heart sing joyously inside me”.

Nature is an endless source of inspiration for your music. The changing scenery through the seasons, mirrored on the still surface of a millpond... But the references to persons are much less and very different, people are like abstract souls, like an aura. Do you find depictions of human characters less attractive, or more difficult to be described? Nature is an endless source of inspiration for your music. The changing scenery through the seasons, mirrored on the still surface of a millpond... But the references to persons are much less and very different, people are like abstract souls, like an aura. Do you find depictions of human characters less attractive, or more difficult to be described?

Simon Huw Jones: I hadn’t realized this before but you’re right. When I listen to the music, before I have written a vocal melody and words, it tends to take me to places… landscapes or rooms, towns, the ocean… whatever. As a lyricist I like to move into and through theses scenes but also I like to leave a lot of the details, and characters left open to interpretation.

That said, we could try and create some portraits in the future… it could be an interesting experiment.  The Millpond Years is difficult, dark, poetic, angry and haunting. How was the atmosphere during its recording, or the concerts of this time? So much tension, and creativity leads sometimes to unexpected situations within the borders of a band. The Millpond Years is difficult, dark, poetic, angry and haunting. How was the atmosphere during its recording, or the concerts of this time? So much tension, and creativity leads sometimes to unexpected situations within the borders of a band.

Simon Huw Jones: The atmosphere was very exciting at that time. It was a time of great discovery for me. As we all grew up together the atmosphere within the group was always reasonably stable, this made touring and recording a really enjoyable experience as we could easily be our selves, we had nothing to prove to each other.

The concerts were very intense but they always had been… we were drinking too much at that point but in general we got away with it. When I listen back to ‘The millpond years’ I wish I had controlled my emotions more as the vocal sounds too intense to me now, but it didn’t at the time… not to us anyway. I didn’t realise then that even when I try to sing without emotion there it is still enough.

French and German audience accepted your music really well, but your homeland didn’t ever seem to care a lot. At a glance, it seems rather disappointing. But do you think that this fact protected you from any popularity pressure and helped you to express and advance your unique sound much more healthier and easier?

Simon Huw Jones: These things have contributed towards making us the way we are and our music the way it is yes… but I’m not sure how healthy it was to live for so long in such isolation. Had we moved somewhere where our music was better recognised it could have been helpful creatively and spiritually and our overall conditions as a working band might have been better too if we’d been in touch with other people who were involved in music or the arts in some way.

There was something special about living out in the countryside of course, we drew inspiration from it, and still do as its now part of our lives.  “Blind Opera” is an exceptional song, like a theatrical part, the monologue of the doomed. What kind of pictures emerge when you play this powerful piece of music live? “Blind Opera” is an exceptional song, like a theatrical part, the monologue of the doomed. What kind of pictures emerge when you play this powerful piece of music live?

Simon Huw Jones: I think of the ancient apple trees in the orchard that used to be in front of the house where we lived and I think of them being cut down… which was a very disturbing experience for me. All the branches were cut of and the trunks of the trees stood for a few days, jutting out the earth like tortured figures under the flat winter sky. I think of the lords of Morton, whoever they were and I think of the ancient people who were said to be buried beneath that orchard when it was a grave yard in the medieval period. I think of the trees when they were covered with blossom in the spring and the birds that flew between them. ‘Blind opera’ is about the darkest song we ever wrote.

Your live appearances are very tense, you seem to communicate with the audience though not in a conventional way. How do you feel when playing live?

Simon Huw Jones: When it’s going well I feel more alive than at any other time. The point when we communicate best with an audience seems, strangely, to be when we forget they are there. It takes a special kind of harmony for that to happen.

Klaxon was said to be a turning point in your sound, like a big step in time, or a move from the quiet countryside to the noisy nightlife of a city. What kind of influences led you to compose these specially flavored songs? Are you afraid of changes in life and how do you deal with them?

Simon Huw Jones: Yes, we needed to get away from our roots before they trapped us. ‘The klaxon’ was like the beginning of a musical voyage that took us away from the countryside and out into the world beyond. Justin’s guitar led the way and the rest of us followed.

I don’t think we are more afraid of changes in life than the next person.

So we’re in 2008. In a parallel space, four young boys from a small village decide to form a band. In your days, there was punk. Now, where should they try to find the musical sparkle which would be able to cause that creative explosion in their hearts?

Simon Huw Jones: I have no idea, we were lucky to be around when punk rock came along, it changed everything – I suppose the general rap, house, hip hop scene did something similar in that it is artistically accessible… by that I mean that you don’t need any musical training to start making that kind of music… it’s a good vehicle for raw expression.

So a group in a parallel situation would probably start by writing hip hop songs with a typically urban feel then realize, after a while, that they were writing songs about something that was not a part of their lives… then they would start taking influence from their actual environment or at least stop trying to be something they were not.

Do you feel that you are always open to musical and lyrical influences, from the early years till today? Or do you think that you have come to a final aspect that helps you listen and create music?

Simon Huw Jones: We are always open to influences.

How easy was for Simon to dress up lyrically the 50’s guitar sounds and the American sound of Angelfish and Silver Soul? I mean, as far as I know, first comes the music and then you go on with the lyrics. Did Simon had any difficulty in following the change of the musical context?

Simon Huw Jones: It wasn’t easy at all, although I don’t ever find lyric writing easy. It was an alien landscape to me that conjured up images of Edward Hopper and scenes that reminded me of passages I’d read in Fitzgerald novels or beat novels. The only way I felt I could do it was to look upon it as a voyage.

Your latest album "(Listen for) The Rag and Bone Man" continues in the same vein as your previous "Further From The Truth", but one might say a little darker, maybe dreamier. What was the band’s approach towards the new songs while recording? Your latest album "(Listen for) The Rag and Bone Man" continues in the same vein as your previous "Further From The Truth", but one might say a little darker, maybe dreamier. What was the band’s approach towards the new songs while recording?

Simon Huw Jones: The general opinion, and ours too, is that the latest album is quite different to the one before it – although I accept that we don’t all hear things the same way. Apart from the musical and instrumental differences, ‘(Listen for) the rag and bone man’ has quite a different lyrical feel to it too, the words certainly came from a different area of my head.

What’s a “Rag and bone man”?

Simon Huw Jones: Originally rag and bone men went from house to house collecting rags (pieces of old cloth) which were used as an ingredient to make paper, and bones - which were used in the making of china. Times changed and rag and bone men turned to collecting just about anything they thought they could use or sell.

Why so much violence in “The Legend Of Mucklow”? The voice, the lyrics, the sounds, they are scaring. An astonishing, unexpected murder ballad, for sure, but quite unusual. Why so much violence in “The Legend Of Mucklow”? The voice, the lyrics, the sounds, they are scaring. An astonishing, unexpected murder ballad, for sure, but quite unusual.

Simon Huw Jones: There is an undercurrent of violence in a lot of our music, although it doesn’t usually come to the surface. In ‘The legend of Mucklow’ it does, there was something very menacing about the music and the more I heard it the more my mind was drawn to this character. I’m not really sure what is going on in this lyric, the violence is quite abstract and what part Mucklow takes is unclear. He was actually hung for the theft of livestock (so the legend has it) and his phantasmic figure does still ride the lanes, but what he is doing in this song I don’t know. I actually like this ambiguity.

When do you think that something could be described as “classic”? Is it a matter of time, quality, popularity, or …

Simon Huw Jones: I suppose it is a combination of all those things although I’m not sure about ‘popularity’… I consider ‘No more shall we part’ to be the ‘Classic’ ‘Bad seeds’ album, for example, but I’m not sure it is his most popular.

Have you ever felt inspirationally and musically exhausted?

Simon Huw Jones: Yes, many times.

Which are your favourite poets? Which poem could sometime stand as lyrics in a song of yours?

Simon Huw Jones: Actually I am not a good reader of poetry… my favorite are probably collections of Haiku poems.

What was you opinion of the Greek audience when you first played here in Athens in 2004? It was a concert that many had been waiting for a long time.Any chance to come & play again some time soon? What was you opinion of the Greek audience when you first played here in Athens in 2004? It was a concert that many had been waiting for a long time.Any chance to come & play again some time soon?

Simon Huw Jones: We had a very good time when we came to Athens, we got on wellwith every one we met and had a very strong feeling from the audience. We want to come back but of course the traveling is problematic. We have been talking with our contact about returning sometime this year though. I really hope so.

Please give us a word or two, (a characteristic, a name, a person, a feeling…anything!) that occurs to your mind, when reading the followings. I always liked that little game!

Inkberrow - I now spell it ?nkberrow

Robert Smith - Good guy in a knackered biker jacket Slow Pulse Boy - A Belgian backstreet England - home, unrealistic green hills dotted with sheep. The Fruit Room - jasmine and the bed with sun light over it. Home. Romance - An old book I flick though the pages of but never read Art - The wonderful Tate gallery The Young Gods - Good neighbors to have Lol Tolhurst - Sun glasses Stay away from the accordion girl - stars above a vineyard. And also the trees - Standing outside a fish and chip shop after doing our first gig - amazed and happy... where do you take me my little girl - indeed.

Interview by: V. Giannakopoulos

N. Drivas

AND ALSO THE TREES - Lady d'Arbanville video 1989

|

On the rust red lane ...

And Also The Trees new album is called Hunter not the Hunted and was released March 26th, 2012.» Other Projects: November, Simon's collaboration with Bernard Trontin of The Young Gods had been released on the swiss label Shayo Records (Martyn Bates, Sally Doherty, Julia Kent a.o.)Steven Burrows currently is working on a solo project (called 'Black River') and will be featured as guest musician on the upcoming Dark Orange album as also Emer will be. » Beyond The Horizon ...A Homage to And Also The Trees e-mail me for infos if you want to contribute with a song Untangled... |

DECEMBER 01, 2012» A new combination of noise Simon Huw Jones did vocals to Olivier Mellano new work How we tried a new combination of notes to show the invisible or even the embrace of eternity. It had been be released on Naive Classique on 6th November as a 3 CD+DVD boxed set: Simon Huw Jones did vocals to Olivier Mellano new work How we tried a new combination of notes to show the invisible or even the embrace of eternity. It had been be released on Naive Classique on 6th November as a 3 CD+DVD boxed set:The first disk features the original symphonic version written by Oliver Mellano and performed by the Symphonic orchestra of Brittany with soprano Valérie Gabail on voclas. On the second disk Mellano transcribes the classical version to a 'electric/noise' version with seventeen electric guitars, percussion and featuring Simon on vocals. And the 3rd CD is 'Electro/hip-hop' version featuring 'MC dälek', Black Sifichi and 'Arm'. Included in the box-set is also a DVD of the award winning film made for the piece directed by Alanté Kavaité. How we tried a new combination of notes... will be performed live - all 3 versions one after the other - as part of the 'Trans musicales festival' at the Opera House in Rennes on December 7th, 8th and 9th. You can order the box-set from amazon France and amazon Germany Detail Information of the versions included in the box set: Version symphonique : How we tried a new combination of notes... Orchestre symphonique de Bretagne Jean-Michaël Lavoie : direction Valérie Gabail : soprano Click to see the Trailer Video for this version Version électrique : How we tried a new combination of noise... Olivier Mellano Pink Iced Club : ensemble de 12 guitares électriques Simon Huw Jones : voix Click to see the Trailer Video for this version Version électronique : How we tried a new combination of one/o... Mc Dälek & Black Sifichi : voix Didier Martin : Lumières Taprik, Dan Ramaën : Vidéos Click to see the Trailer Video for this version SEPTEMBER 15, 2012 » Hunter Take Away Videos

Alexandre François and Gaspar Claus produced four acoustic "take away videos" for And Also The Trees in Paris last winter. They are now released in the series Les Concerts A Emporter on La Blogothèque.

They feature "A woman on the Estuary", "Whisky Bride", "Only" and "Burn Down This Town" with commentaries from the band what these songs are about. And from the video producers about the day of shooting of these videos. Do not miss this excellent insightful presentation presented by La Blogothèque, the guys which also brought you the unique 'Back on Stage' footage of Paris La Maroquinerie 2007. SEPTEMBER 10, 2012 » A new combination of Noise

Teasor form the upcoming collaberation between Olivier Mellano and Simon Huw Jones ...

For anyone who missed it: Simon also sang a duet with Lena Fennell to her beautiful song 'Nauticus'. Lena Fennell had been the singer to 'Roulette' - the BTH version of Magnetfisch: AUGUST 30, 2012

The And Also The Trees documentary of Radio Dijon Campus has finally been released. Don't miss viewing this terrific footage including new interviews with Justin and Simon. And a lot of concert footage of the Hunters' concert 2012 in the wonderful location of Hotel de Vogue in Dijon.

Thanks for that jewel Sebastien Faits-Divers! JUNE 15, 2012 » ... touring the Hunters

From 13th. April on the 'Trees are on the road touring the "Hunter" album, the largest tour since years spanning France, Germany, Denmark, Austria and Italy.

Please share these live experiences and your personal concert impressions in the comments. APRIL 04, 2012 » Hunted

Got the new album already?? Share your first thoughts and impressions & post your hunted weblinks of album reviews & interviews in the comments.

Great bunch of reviews & Impressions so far. Thanks! ... Keep them coming!! JANUARY 28, 2012 » Hunter not the Hunted The new And Also The Trees album is titled "Hunter not the Hunted". It will be released for retail and online shops on March 26th 2012. And can be ordered as CD and special double 10 inch gatefold vinyl version (with bonus track) from March 06th onwards here. And Also The Trees present ‘Hunter not the Hunted’ as an entire ‘novel’ of an album. The album’s subtle shadowed beauty and intense quality are a result of recent intimate live shows in bizarre spaces, where the proximity of the audience enveloping the band, created a unique and magical feel reflected in this work. Hunter not the Hunted breathes and pulsates with its own pace. Order at amazon.de, amazon.fr JANUARY 27, 2012 » Othon Impermanence

Justin Jones joined Othon Mataragas as guest performer in one song of the artists' upcoming new album: "Impermanence". Othon also works with Marc Almond, David Tibet and Ernesto Tomasini and the Elysian Quartet.

The album launch with Ernesto Tomasini is on the 28th November 2011 @ Chelsea Theatre, London as part of Sacred festival with special guests Marc Almond, Justin Jones (And Also The Trees) and Laura Moody (Elysian Quartet). Symphonic beats by Hugh Wilkinson.

Labels: Collaborators

OCTOBER 23, 2011» Goodbye Ivan feat. Simon Huw Jones

Anxiolytics (The Visit) a vocal written and performed by Simon features on the new 'Goodbye Ivan' CD 'intervals' released by Shayo records.

Simon will also be performing the song live at the release party on Saturday 29th October at the small theatre in L'Usine, Geneva, where 'Goodbye Ivan' will be performing the album in it's entirety with other guest musicians that feature on the album.

Labels: Collaborators

OCTOBER 10, 2011» Driftwood And Also The Trees released a new mini album called Driftwood as a limited edition of 1000 copies. Like When the Rain Comes Driftwood featues eight acoustic versions of songs selected from the bands history. The mini album had been recorded after the live touring in 2009/2010 and is only available from the band's webpage. And Also The Trees released a new mini album called Driftwood as a limited edition of 1000 copies. Like When the Rain Comes Driftwood featues eight acoustic versions of songs selected from the bands history. The mini album had been recorded after the live touring in 2009/2010 and is only available from the band's webpage.

OCTOBER 07, 2011

JUNE 09, 2010» Premonition Special Issue Online

In November 1991 the french fanzine Prémonition dedicated a special 40-pages issue of their magazine to And Also The Trees. It included an (early) history, in-depth interviews with Justin and Simon Huw Jones, questions with all band members, a discography and reviews of ALL albums, EP's an compilation until 1989, a short live history, hand written lyrics of Simon ... and an exlusive CD with three live tracks from the now legendary concert in Paris La Bataclan 1989.

The publication had a limited print of 500 is now a well sought-after, expensive collectors item, near impossible to find ... Good news for all fans not having this publication in their hands: Prémonition have officially put thisspecial print online including all three live tracks: Click here to head to that excellent publication! Thank you Twamodd ... and special thanks to all people from Premontion (Yannick, Guillaume, Oliver, Dominique, ...) |

Twenty years of work, fertilising, harvesting and also the trees. Such jubilee.

Steven: "Yes, it should be the cause of some celebration. We seem to have survived by some beautiful accident rather than by design. When we began our only hopes were to make one record and play some shows! But the time has passed very quickly. It's been an exciting & often magical journey, and one that will continue for as long as music has an importance in our lives. I think we have a lot to be proud of. We have never made a record that we didn't like...we have never compromised our music for commercial reward...and we have never been part of a fashion or 'scene' (although others have tried to put us there!). We have an incredible bond of friendship within AATT & this has been the key to our longevity. Even the ex-members (Graham, Mark, Will, Emer, etc) remain great friends"

Does Byron & Constable done in the field what you did in the meadow?

Steven: "I'm flattered that you would consider us in the same league, and it's a fair observation, but one that I think now belongs in our past. In the period between Virus Meadow & Farewell To The Shade we lived & breathed the countryside. Nature was our everyday enviroment and it was absorbed completely into our music. It seemed impossible to avoid it. Our home village of Inkberrow was - and remains - a beautiful place, but over the years it has changed, like everything else. There are more people, bigger roads, more noise, and it's connection with AATT has gone. We all live in urban landscapes these days. Enviroments that have a poetry & beauty all of their own...."

Something about you l'unica strada way of living...way of playing. ?

Steven: "AATT has taken us halfway around the world. These journeys have altered our lives to the point where music & life have become one entity. Each has an influence upon the other. 'Farewell...' for example was written after lengthy visits to both Italy & Germany,and had an enormous effect on the way that we wrote the album, both musically & lyrically. If you listen hard you can hear the influence quite clearly. This process carries on even now, in the Americana of our last two albums 'Angelfish' & 'Silver Soul'. Music as memories. Quite a juxtaposition from the englishness we've become famous for, and one that's not lost on us....it's bizarre that I can feel so English when I visit the USA, but when I am home I feel more European than English!"

Does urbanisation bring crooked emotions?

Steven: "It brings more emotions & different emotions, but no more crooked than in the countryside...our lives are shaped by the people we allow into them & by default we experience more people in an urban enviroment. On a personal level I think we are all much happier living in urban landscapes. The isolation of the rural world can be wonderful, but like everything it has it's dark side..."

The fragrancy of Lady d'Arbanville & tenderness of The Woodcutter becomes our regular repertoire & response of audience is very well. How important to you are peoples reactions on your songs?

Steven: "It's very important as this is the proof that we are making a connection on a personal level, that what we are doing is as important to someone else as it is to us. And sometimes the audience is our objective ear. They instinctively know if a piece of music is good or bad (and sometimes they will let us know!) But we have never let our audience dictate to our musical direction. We have often been told that we could have been more successful if we had given our audience exactly what they wanted, but we have always felt the need to be honest with our music. We are instinctive artists, sometimes with little control over our direction. Only once did we try to make a popular record -The Secret Sea - but in our opinion it was not a success, a lesson learned. It would be impossible to be passionate about our music if we were not honest in it's creation...

Give me an ounce of civet, good apothecary, to sweeten my imagination about your new album...

Steven:"It is in a very early stage so it's difficult to give a true picture. There have been personal tragedies in our lives that may shape its colour. I anticipate it will be much darker than our last album....our fascination with Americana seems to be disappearing & is being replaced with a sparse, dark, jazz feel. We're trying to experiment with new sounds and of course we have a new drummer - Paul Hill - who replaced Nick last year, so there will be some changes that are completely natural. We're listening to Miles Davis, John Cale, Tom Waits, Kraftwerk & Underworld, & I detect a return to a more 'European' sound..."

Interview of Simon Huw Jones

by Ivor Thiel

October 12, 1998.

Hello. So, this was the new album, Silver Soul. Took nearly two years, about two years. Why did it take this long period to get the album out? I heard you changed labels, was it all because of this?

Simon We usually take two years, anyway, to write each album. But we did change the label, and did have a few difficult times with the business side of music.

Well, a lot of people were frightened because they thought that maybe there never would be another album. In the past few years when I'd play And Also the Trees, people phoned up and asked "When will there be another album?" All that I had heard was that you didn't have a new label. Now, finally, you've found one. How did you manage to get to them? Why them?

Simon : It's our own label. The first CD on our own label.

And who is doing all the work? It's a lot of work, I think, running your own label.

Simon : Guitarist and brother Justin. We're doing distribution through EFA.

Why did you do your own label, and choose to produce your own work?

Simon : We'd had a lot of trouble with other labels. In fact, the English label we signed to were enthusiastic and convinced that they could make us more popular in England. Now, this wasn't Reflex, this was the one before Silver Soul, we just had the one CD with them. But they didn't get very far, because we have not really spoken with the media in England for about eight years. So, I think they've fallen out with us forever. And we don't really care about that, but the record company had a lot of trouble and we decided to sort of leave them and go on our own.

Well, when you do it on your own, I suppose at least you know exactly what happens to your CDs, because you have all the work in your own hands.

Simon: Exactly.

You just said that you didn't talk to the media in England for about eight years. I know that a lot of bands are telling me that if the media likes you there, you're the best band for a week or a month, but if they don't, then they don't speak to you. What's the media situation in England?

Simon : I don't know. I think it was about 1986 or 1987 the first time we came to Europe, and we had a very good time, and at that point we were getting pretty good press in England. When we got back, we didn't speak to the media and they didn't speak to us. We really couldn't be bothered to do all the running around and telephone calls, trying to be friends with people who you're not friends with. All that falseness. And we just decided that we weren't going to bother.

So you didn't care at all about that.

Simon : Not really, no.

I saw on the tour, you only had one gig in England, and it's right where most of the band lives.

Simon : It's near to where most of us live. In fact, it was our first gig in England in six years.

But, I heard it was a good gig.

Simon : It was a good gig. We really enjoyed it, and the crowd really enjoyed it. I was quite pleased because a lot of people who knew nothing about And Also the Trees came ready to criticize us, and they liked the gig a lot. So, for me that made it particularly worthwhile.

So maybe there will be an English tour soon.

Simon : There was an agent who asked us afterwards if we would do a tour, but of gothic clubs, which we're not so keen on. But maybe, maybe we will.

The Obvious. Something special to say about this song?

Simon : Lyrically, I thought of the lyrics when I was in Bern. I was living there for six months. I loved living there. The idea come to me as I was walking home from the supermarket down the big old main street one night. For me, it's quite special for that.

T Isn't it difficult for you to live most of the time in Switzerland, with most of the band in England, in Inkberrow, I believe, to produce the new album? How did you manage it?

Simon : Well, what happened, Justin and Steven wrote the music, and then last spring, Justin came to Lugano ,on the Italian border near where I was living then with some recording equipement. We cleared the flat that I was living in, and I surrounded myself with books and bits of writing that I'd done, and just sang whatever came out of my head or the books or whatever. We got a lot of the vocal melodies written there, and then he went home. So, yes, it's difficult, but we always manage somehow.

So Justin and Steven do the music first, the bassist and the guitar player, and you later do the lyrics.

Simon :The lyrics and the vocal melody, yeah.

And finally, you produced it in your studio in England, or where?

Simon :No, we went to Cornwall to do that.

Ah. So, ten tracks on the new album. Perhaps you can say something about it? You just talked about The Obvious lyrics you wrote in Bern, is there a special story about Nailed or Rose-Marie's Leaving?

Simon :Nailed. Now this is something that is just very... The music wrote that in my head for me, I think. It had to be urban. And it's almost like this character called Red Valentino from a song of about three or four albums ago, his spirit seems to walk in and out of all of our albums. I think this is a reincarnation of him. And Rose-Marie's Leaving is one of those blissful songs that I wrote the lyrics for as I sang them. It came straight out of my head. It took no time at all. If we could do all the tracks like that, we would do an album every six months instead of every two years.

You say one album every two years, but the band started in the beginning of the eighties. Now we are at 1998, and there should be more albums than eight.

Simon : Yes, when we first started, it was a period of time when bands were recording 12" singles, this is a good excuse this one for being lazy or not prolific enough, but in those days bands were doing 12" singles with two tracks on the B side, and one on the A side, and not including those songs on the albums.

Thiel That's right, I remember. I even have here the box of all the singles and 12" maxis. I remember the only cover version I know from And Also the Trees was from a Maxi, it was in the sum of Cat Stevens. Why did you cover this song, and have never done another cover?

Simon :Yes, Lady D'Arbanville. Well, that was a song that I'd grown up with. My sister was a bit of a hippie in the sixties, and she used to be in love with Cat Stevens and would play that song, and it stayed with me for a long time. And that was a time when the group, we were quite influenced by the romanticism and color of the pre-raphealite paintings. That was a song that just seemed to fit in.

The last time I played Rose-Marie's Leaving, someone phoned me up and asked me if this was a new song from Nick Cave.

Simon : Really. Oh, well...

It's probably the first time that someone has told you this. I don't see too many common things between this song and Nick Cave. Perhaps it's because it's a little bit slower.

Simon It's the blues influence, isn't it?

Yeah, probably. So, let's have a last few words about this wonderful song, it's called Highway 4287. Listening to your last two albums, the lyrics, for one, are getting more urban. And also, it's incorporating different musical types, a little blues, a little jazz. Can you say something about this?

Simon : Well, the way I see it is that if And Also the Trees has a spirit as a group that's the music rather than the members, then it's almost as if it emigrated to America about three albums ago, and it's now coming forward in time, I think. At first, we were interested in the F. Scott Fitzgerald 1920's and 1930's America. And now it seems to have gone forward after the jazz age and it's sort of going towards the blues period and a bit of the 60's America with the wah-wah guitars coming in as well. It's not preconcieved, but it's just the way it seems to be happening.

Something about the more urban character perhaps, is because civilization is getting nearer and nearer to your parents house?

Simon : No, I don't think it's that, I think it's because I have been travelling a lot, and the rest of the band have been travelling.

I see. So, do you want to say any last words about the concert, or what people can expect tonight from the Silver Soul tour?

Simon : Well, I think if you've seen And Also the Trees before, then you'll enjoy it tonight, because it will be a bit different. People are saying that there is a sort of power and energy that wasn't there before. And the people who haven't come to see us before, I think that the Trees are quite a different experience.

Stylishly living in times of chaos

Interview by Christian Cerboncini

From Entry (August 1996)

From Entry (August 1996)

One of the most positive appereances on the this year's Zillo-Open-Air in Hildesheim was surely And Also The Trees, who only had their second festival gig in Germany since their appearance on the bizarre festival years before. Unfortunately they must do this always in the afternoon at glistening sunlight, which does not fit so completely with the atmosphere of the songs.

Wasn't it rather hot on stage with your coat?

S.H.J.: No, it was OK. In a night club it is more hot with the whole lights in such a small room.

Have you been satisfied with your gig, with the sound, with the people?

S.H.J.: Yes, I was completely satisfied. It was not fantastic however, but under the circumstances, we have done the best possible. Our playing was quite OK and the sound was evidently in order as well. It was fun for us and it appeared to me, as if it has pleased the spectators also, therefore what do we want more ...

S.B.: It is always remarkable, if one goes on stage in the middle of the day and plays without sound check.

And it is unusual for the spectators to see you in the lightest sunshine, club athmosphere fits your music better.

S.H.J.: l believe too that we are more of a club band, but it is also fun to play in front of so many people, especially if they are like here.

How is it like to play old stuff, as e.g. "Slow Pulse Boy" which is approx. 13 years old; isn't that odd?

S.H.J.: No, no, it's not, especially since this is a song we like to play again and again, because it is fun for us to play it. "Slow Pulse Boy" is a song where something can go wrong everytime, today, for instance, something went wrong and in the middle we lost it somehow ...

S.B.: ... totally lost it ...

S.H.J.:... and that is the exciting part: we can play the song 287 times live and nevertheless we can always do something wrong and correct it and still enjoy it somehow.

S.B.: It is also not a simple song to rehearse. We did it a couple of days ago and we realized that we had played it too often, somehow it did not work.

As you've said a little while ago, you enjoy more playing in small clubs than large festival?

S.H.J.: I think we are more suitable for clubs.

S.B.: But festivals also have advantages: You see and hear several other bands and also you can finally see the spectators: in clubs you can at most recognize the first three rows, which however sometimes can also be good.

S.H.J.: It is our first festival since 5 years. Besides such an appearance is also always a chance for people, who absolutely would not go to one of our concerts, to see AATT live once.

: Did you have contact to any other band?

S.B.: A few times yes. Near the stage I spoke with some of the Walkabouts, and also Frank Black stood around there and everyone had a good time and seemed to enjoy it. But it is a strange place here; at festivals bands are normally housed together in a large area. Here everyone is separated from each other.

Yes, the whole thing reminds me of a prison cell. What have you been doing since the last album and why did it take you so long to finish "Angelfish"?"

S.H.J.: Well, we finished the recordings for "Angelfish" already in the last fall. The whole record company nonsense took a long time. We namely changed the label.

Previously you were on the label Normal; any problems there?

S.B.: It is difficult to talk about it, because there was not only a problem between us. It simply somehow didn't work no more, so we decided to try something new, and now everything is in order.

Is Mezentian a new label?

S.B.: Yes, it is the first release on this label, and although it is too early to say something about it, I believe that it is going to become totaly good.