Dokumentarac napravljen prema knjizi Chrisa Hedgesa. Masovni mediji samo su maskirana propaganda. Korporativni fašisti, tvorci uništenja, marširaju dok se mi, robovi, veselimo. Treba nam pobuna, ne revolucija.

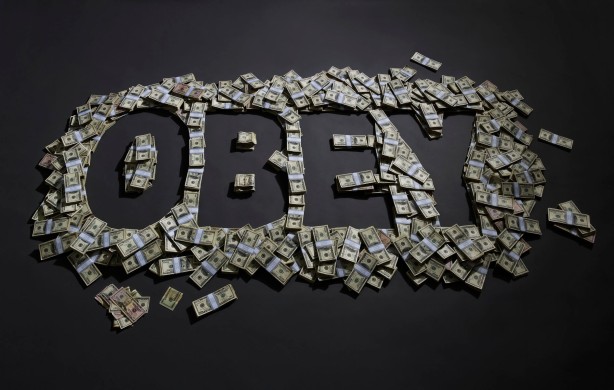

'Obey': Film Based on Chris Hedges' 'Death of the Liberal Class'

British filmmaker Temujin Doran has released a new movie that is based on the book "The Death of the Liberal Class" by Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges. The film, titled "Obey," explores the rise of the corporate state and the future of obedience in a world filled with unfettered capitalism, worsening inequality and environmental changes.

British filmmaker and illustrator Temujin Doranhas previously delighted and stimulated us with his visual love letters to language and illustration, his opinionated meditations on democracy and theart of protest, and his poetic documentaries abouta small Arctic town and a dying occupation. His latest film, made entirely out of footage found on the web, is based on the book The Death of the Liberal Class (public library; UK) by cultural critic and foreign correspondent Chris Hedges and explores how the rise of the Corporate State precipitated everything from income inequality to environmental collapse to the mainstream media’s metamorphosis from a tool of public service into a weapon of private interest.

British filmmaker and illustrator Temujin Doranhas previously delighted and stimulated us with his visual love letters to language and illustration, his opinionated meditations on democracy and theart of protest, and his poetic documentaries abouta small Arctic town and a dying occupation. His latest film, made entirely out of footage found on the web, is based on the book The Death of the Liberal Class (public library; UK) by cultural critic and foreign correspondent Chris Hedges and explores how the rise of the Corporate State precipitated everything from income inequality to environmental collapse to the mainstream media’s metamorphosis from a tool of public service into a weapon of private interest.

“Obey”: A Brutally Honest New Film By British Filmmaker Temujin Doran

Posted by Gabriel Roberts on March 22, 2013

“A chilling view of the future”

“A harrowing tale of what we may become”

Based on the book The Death of the Liberal Class by Truthdig columnist Chris Hedges, “Obey” brutally conveys our present reality, perhaps in the hope that we may finally wake as a united humanity.

We have been lulled into a state of being in which we are not confronted with monolithic decisions where we choose Liberty or Death; instead we are fed a steady diet of mini-compromises in our lives that we often choose wrongly upon.

I myself and totally guilty of this, but the overall result is a total compromise of every single piece of our dignity and personal sovereignty. So say that things are as they truly are is a radical notion that may get you shot in the face with a gas canister, like the military veteran of the Oakland Occupy protests or thrown into prison indefinitely like Bradley Manning.

This film begs the question, “will you remain quiet, little bitch?’ to which we may very well whimper internally, “yes, as long as I can keep my health insurance and am able to feed my kids”. It reminds me of when Jim Morrison yelled to the crowd, “You’re all a bunch of slaves!”.

In case you didn’t notice, this film made me angry and rightly so. See for yourself and make your own judgements.

Obey: How the Rise of Mass Propaganda Killed Populism

by Maria Popova

“A populace that can no longer find the words to articulate what is happening to it is cut off from rational discourse.”

British filmmaker and illustrator Temujin Doranhas previously delighted and stimulated us with his visual love letters to language and illustration, his opinionated meditations on democracy and theart of protest, and his poetic documentaries abouta small Arctic town and a dying occupation. His latest film, made entirely out of footage found on the web, is based on the book The Death of the Liberal Class (public library; UK) by cultural critic and foreign correspondent Chris Hedges and explores how the rise of the Corporate State precipitated everything from income inequality to environmental collapse to the mainstream media’s metamorphosis from a tool of public service into a weapon of private interest.

British filmmaker and illustrator Temujin Doranhas previously delighted and stimulated us with his visual love letters to language and illustration, his opinionated meditations on democracy and theart of protest, and his poetic documentaries abouta small Arctic town and a dying occupation. His latest film, made entirely out of footage found on the web, is based on the book The Death of the Liberal Class (public library; UK) by cultural critic and foreign correspondent Chris Hedges and explores how the rise of the Corporate State precipitated everything from income inequality to environmental collapse to the mainstream media’s metamorphosis from a tool of public service into a weapon of private interest.We unite behind brands, behind celebrities, rather than behind nations. We have become more than nation states — we are corporation states.

The opening of the film comes from the epigraph to The Death of the Liberal Class, in which George Orwell reminds us:

At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.

TEXT BYTETSUHIKO ENDO

PHOTOGRAPHY ED ANDREWS

HUCK speaks to award-winning illustrator and documentarian Temujin Doran about his new film, Obey.

The other day, I was minding other people’s business on Facebook last week when my favourite dark prophet of this doomed generation,Cyrus Sutton, posted a video called Obey. Seems innocent enough, right?

The video in question concerned the rise of propaganda under the guise of mass media and how it’s dumbing down global culture to near catatonic levels. Fifty one minutes later I was emailing it to my friends and family while trying to track down its creator, 28-year-old Temujin Doran.

By day Doran works as an award-winning illustrator and documentarian. By night he joins that dying breed of movie auteur, the 35mm film projectionist, in a job at a single screen cinema in Islington, London. Whether with pen and paper or camera or both his work is not to be missed.

When I reached him, via email, he was kind enough to answer some questions I had about filmmaking, commercialism, and even the future of the world.

How did you get into filmmaking?

I studied illustration, but I would make short films in my spare time, mostly to amuse my friends. After graduating, I travelled a lot, then moved to London and started working as a projectionist in a cinema, alongside illustrating. While that was going on I started to make short films in my spare time; often editing in the projection booth.

I studied illustration, but I would make short films in my spare time, mostly to amuse my friends. After graduating, I travelled a lot, then moved to London and started working as a projectionist in a cinema, alongside illustrating. While that was going on I started to make short films in my spare time; often editing in the projection booth.

Do you think the current state of media and communications technologies offers any advantages to filmmakers today?

With regards to film, I’m continually hearing that it has never been a better time to be in the film industry. Cameras and equipment are becoming cheaper and more accessible, and those wishing to forge a career in the film industry have a huge number of avenues to secure funding through competitions, corporate sponsorship and a growing number of international film festivals and crowd-sourcing websites. After all, more often than not, it is funding that makes films. So more and more people can make films, and more and more films are being made – from huge blockbusters to small independent features and shorts. “A democratisation of the medium,” some experts might call it.

With regards to film, I’m continually hearing that it has never been a better time to be in the film industry. Cameras and equipment are becoming cheaper and more accessible, and those wishing to forge a career in the film industry have a huge number of avenues to secure funding through competitions, corporate sponsorship and a growing number of international film festivals and crowd-sourcing websites. After all, more often than not, it is funding that makes films. So more and more people can make films, and more and more films are being made – from huge blockbusters to small independent features and shorts. “A democratisation of the medium,” some experts might call it.

But I really feel that this can be a double-edged sword. Almost all corporate-led film competitions or challenges are little more than glorified adverts for products. Short films must be scripted to include key merchandise or locations that fit with a brand’s market strategy. Many of us are repulsed by the blatant advertising that we see on TV – commercials without tact or subtlety – but these themes are increasingly working their way into the film industry. Talented new writers and directors are having to bend their passions, submit to brand direction and learn the language of business.

What about crowd funding?

Crowd funding similarly requires creative people to turn themselves into marketeers to source money. Now, that’s admittedly an incredibly cynical viewpoint, and not that one that I completely agree with, either. Crowd funding is a great way of getting interesting projects off the ground, and new filmmakers can use the attention brought to them from commercial work to go on to make films about subjects they are passionate about. But I think it’s interesting to see that in a time of economic crisis, government money directed to the arts and filmmaking is being cut in many countries. And what we are seeing is the world of business, the corporate giants, who are stepping in to take that place. It’s not just business, but the mindset of business, so that working in the film industry really can start to become less of a creative endeavour and more of a corporate marketing profession.

Crowd funding similarly requires creative people to turn themselves into marketeers to source money. Now, that’s admittedly an incredibly cynical viewpoint, and not that one that I completely agree with, either. Crowd funding is a great way of getting interesting projects off the ground, and new filmmakers can use the attention brought to them from commercial work to go on to make films about subjects they are passionate about. But I think it’s interesting to see that in a time of economic crisis, government money directed to the arts and filmmaking is being cut in many countries. And what we are seeing is the world of business, the corporate giants, who are stepping in to take that place. It’s not just business, but the mindset of business, so that working in the film industry really can start to become less of a creative endeavour and more of a corporate marketing profession.

Would you say this is a new trend?

No, that’s not to say it’s never been like this before. It was in 1964 that Marshall McLuhan said that movies didn’t need advertising intervals because “the movie itself is the greatest of all forms of advertisement for consumer goods.” In some ways, a film can be the perfect advert. It might not always be selling a product or goods, but more than this, it can sell an idea. And this is probably more affecting and dangerous. The tedious lineup of adverts we have to sit through before a films starts in the cinema, can scarcely compete with the themes of the film itself. And if it happens to be a consumerist, capitalist lifestyle that the film portrays and exults then the adverts that came before the film don’t really have to try that hard to sell you something if you’re already half way there.

No, that’s not to say it’s never been like this before. It was in 1964 that Marshall McLuhan said that movies didn’t need advertising intervals because “the movie itself is the greatest of all forms of advertisement for consumer goods.” In some ways, a film can be the perfect advert. It might not always be selling a product or goods, but more than this, it can sell an idea. And this is probably more affecting and dangerous. The tedious lineup of adverts we have to sit through before a films starts in the cinema, can scarcely compete with the themes of the film itself. And if it happens to be a consumerist, capitalist lifestyle that the film portrays and exults then the adverts that came before the film don’t really have to try that hard to sell you something if you’re already half way there.

In fact, I’m pretty sure that this concept of consumer advertising in film is actually a function that many people will consider a passion. If that’s the case, the current state of affairs has never been better! It still requires a lot of talent, and the individuals who excel at this work are incredibly creative. But it seems quite a sad thought. Again, that’s truly cynical, but still important to think about, at the very least. I’m probably going to have some difficulty convincing you that I’m quite an optimistic person…

In terms of communications and films, the vehicle for getting recognised and expanding your audience is no longer limited to just film festivals. The number of people who will be able fit into a single screening of a film at Sundance or the Berlin Film Festival is insignificant to those who will see it online. And the producers, creative scouts and other people who you will want to see your film all have the internet too. Now they just need to like what you’ve made.

Can you talk about some of the different things that inspired you to make Obey?

I’ve made short films on similar subjects before, but for some time I’ve wanted to make a much longer film that explored this idea of political helplessness and obedience. A friend lent me a copy of Death of the Liberal Class by Chris Hedges around the same time and I found it so well written – not just convincing, but passionate and articulate. If the film does nothing but encourage people to seek out the book, I’ll be happy.

I’ve made short films on similar subjects before, but for some time I’ve wanted to make a much longer film that explored this idea of political helplessness and obedience. A friend lent me a copy of Death of the Liberal Class by Chris Hedges around the same time and I found it so well written – not just convincing, but passionate and articulate. If the film does nothing but encourage people to seek out the book, I’ll be happy.

I read that the film is made entirely from web clips. How long did it take to assemble them into the final product?

I started the film in September last year and finished in February this year. I did it in my spare time, but it was quite a laborious process of just hunting the web for the right clip to use. I really think I’ve seen far too much of the internet in the last six months.

I started the film in September last year and finished in February this year. I did it in my spare time, but it was quite a laborious process of just hunting the web for the right clip to use. I really think I’ve seen far too much of the internet in the last six months.

The work is pretty dystopian and cynical about the future. Do you think global societies are all doomed?

Yes, the film is dystopian and cynical about the future, but it only presents a possible future – not one that will necessarily happen. When the film is reversed at the end, it’s my hope that people will realise that all of what they’ve just been presented with is merely an option; not an ultimate destiny, but one possibility of many.

Yes, the film is dystopian and cynical about the future, but it only presents a possible future – not one that will necessarily happen. When the film is reversed at the end, it’s my hope that people will realise that all of what they’ve just been presented with is merely an option; not an ultimate destiny, but one possibility of many.

What do you think the future holds?

Well, I guess I certainly consider such a future possible – enough so that I made a film about it. But I think what is more important than what the future will be like is ‘what is the future that we deserve?’ That’s not to say that we should just abandon hope and get what we’re given – the future is, after all, what we make of it (Haha - Terminator 2!). But we only deserve a better future if we make one, and that only happens with our actions now. If we do nothing to improve our future, then we get a rubbish one. I guess that’s why I used the Pindar quote at the end of the film.

Well, I guess I certainly consider such a future possible – enough so that I made a film about it. But I think what is more important than what the future will be like is ‘what is the future that we deserve?’ That’s not to say that we should just abandon hope and get what we’re given – the future is, after all, what we make of it (Haha - Terminator 2!). But we only deserve a better future if we make one, and that only happens with our actions now. If we do nothing to improve our future, then we get a rubbish one. I guess that’s why I used the Pindar quote at the end of the film.

Closing thoughts?

I find it really interesting that most people are willing to acknowledge and accept a dystopia when it comes to fiction films. They can watch many films set in a future in which governments are totalitarian and the environment is completely degraded and they can be utterly entertained. But as soon as you tell them that it might happen for real, or that the beginnings of such a future are already in the works, then more often than not, it gets flatly rejected. It’s probably because the films that suggest such a future don’t have enough explosive action scenes in them or famous people that come and save the day. Instead, we need to save ourselves.

I find it really interesting that most people are willing to acknowledge and accept a dystopia when it comes to fiction films. They can watch many films set in a future in which governments are totalitarian and the environment is completely degraded and they can be utterly entertained. But as soon as you tell them that it might happen for real, or that the beginnings of such a future are already in the works, then more often than not, it gets flatly rejected. It’s probably because the films that suggest such a future don’t have enough explosive action scenes in them or famous people that come and save the day. Instead, we need to save ourselves.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar