Dokumentarac o jednom od najvećih osobenjaka vizualnih medija. Bio je i u ranoj postavi protopunk benda Destroy All Monsters. san mu je dovršiti prog-rock operu (nadahnutu omotnicama ploča benda Yes). Okušao se u 100 stilova i područja rada. Smislio je vlastitu satiričnu religiju O-ism. Njegov niz slobodno stojećih objekata moguće je "čitati" kao knjigu a "strip" mu nije objavljen kao knjiga nego kao niz "izvornih djela" izloženih na zidu.

In conjunction with Jim Shaw’s full-scale exhibition survey of his work, The Rinse Cycle at the Baltic Art Centre (which includes more than one hundred paintings, sculptures, drawings and videos from the last twenty-five years) is this 20 minute feature on the artist, his influences, and the all-mighty Oism.

Collective Vision: An Interview with Jim Shaw

Last fall Jim Shaw published My Mirage(JRP|Ringier, 216 pages, $55.00), a hybrid visual book somewhere between a visual novel, a monograph and a work of omnivorous visual criticism. It collects almost 170 works of art executed between 1986 and 1991 in nearly every medium imaginable. It is an astounding book, perfectly produced, and one that ought to be poured over in comics and art circles for its conceptual and visual ingenuity, emotional heft, and the histories embedded within it. Over the years the My Mirage pieces have been exhibited as a whole only twice, and otherwise it’s been subdivided into smaller groupings hung in galleries and museums. The prints, photos, videos, paintings, drawings and sculptures that comprise My Mirage are each that rare thing: objects that work in space and as part of a book-length narrative. My Mirage (the book and works) is the story of Billy, a kind of zelig of visual culture, who lives out his life through the prism of the culture around him, and manifests each phase of his life, almost like a cultural symptom, through complex reimaginings of artists including Ed Ruscha, De Chirico, R. Crumb, Basil Wolverton, Jess, Jack Chick, Hieronymous Bosch and many, many others.

Billy begins as a repressed boy of the 1950s and grows into and out of hippiedom, 1970s decadence, paganism, and fundamentalist Christianity. We follow Billy and his/our culture as he/it moves through different areas of art, making My Mirage a locus for a truly advanced sense of visual history. Two decades before it became acceptable to do so, Shaw makes no foolish high/low distinctions, imbuing as much meaning in Big Daddy Roth as he does John Baldessari. And so in My Mirage we can glimpse the entirety of visual culture through Shaw’s eyes, but not as static, museum-ready artifacts. Rather, in its evocation of the power and corresponding psycho-social effect of these artists and forms, My Mirageshows what art can do. In that sense it finds its only real prose corollary in Geoffrey O’Brien’s Dreamtime, another book charting an emotional/psychological evolution via the experience of art.

Through it all, as the book’s editor/curator Fabrice Stroun notes in his excellent essay (precisely pitched as an elegant commentary with graphically compelling typography) Shaw maintains a kind of neutral surface. No one work is an exact facsimile — instead all are given an even, almost blank feel. That allows Shaw to be the dominent author, and us to sink into the work without worrying after the particulars. And that’s a very comic strip/book way to go at it — applying an even line, let’s say, to make it all cohere. In terms of the comics medium, My Mirage is especially important for what it implies about the cultural narratives embedded in comics, and how those narratives might be teased out to greater and greater effect as they intertwine with other parts of visual culture. Moreover, as a picture story there’s never been anything like it — Shaw ambitiously allows only a skeletal linear narrative and instead forces us to engage with it as a book, a story, a collection of objects, and a culture, with all of the contradictions that combination brings with it.

Shaw (born 1952) has a long history with his source material, having begun his career in Ann Arbor Michigan, immersed in the trash culture around him and transmogrified it as a member of the Destroy All Monsters collective in the 1970s (the subject of an exhibition I co-curated with the late Mike Kelley a few months back). He then attended the California Institute of the Art at the height of the conceptual movement, and began showing in galleries in the 1980s; in the meantime he worked in special effects for film and television, including Earth Girls Are Easy (1987) and even an early version of Terrence Malick’s film Tree of Life. My Mirage is one part of Shaw’s exceptional body of work, including his landmarkThrift Store Paintings exhibitions and book and his more recent work involving a fictional religion called Oism, which includes multiple comic books presented on gallery walls. He has exhibited in museums and galleries internationally (even crossing into comics as a guest at Fumetto) and will open a show at Metro Pictures, New York, on March 17th.

I emailed with Jim Shaw in January to discuss My Mirage.

As published, My Mirage has taken on the feel of a sequential visual novel, but I know it was created over a number of years in a non-linear fashion. So, was it ever all mapped out on paper or in your head? Was there a grand plan for it?

I always conceived My Mirage as a book and narrative about coming of age in the ’60s done in a fragmented, Burroughs-influenced style using as many different aesthetics as I could muster. Originally it was to be five chapters, about 100 pieces, but during the making I had an idea to expand it with a video per chapter, and there were 3 pieces I felt I needed to eternally research before I felt ready to execute them. So the time frame got stretched way beyond the initial couple of years as my delaying those pieces led to new ideas for further pieces. There are a number of pieces not included in the book because the publishers wanted to stick to only pieces I had good quality 4 x 5s of. I intend to create a web access for those other pieces, but have no idea how, or time or money to pay someone else to do it.

Which three pieces hung you up, and why? And what does research entail for you? Do you practice the rendering method or is it all observation?

Well one was “Mannlicher” [below] which was JFK’s life in the style of Ian Fleming and the aesthetics of its Playboy-excerpting and paperback versions, with a page out of a supposed E. Howard Hunt thriller thrown in to give the assassin’s POV. Another was the Bosch piece ["Chicago 68"] in which all the symbolism, instead of reflecting the concerns of a Dutch Christian in the Renaissance, comes out of Beatles psychedelic lyrics, conflated with elements of the 1968 Chicago demonstrations. I’m not sure what the third one was, perhaps the 4th video…

You have a perverse relationship to picture stories. My Mirage is a series of free standing art objects that can be “read” as a book; and you’ve completed “comic books” that exist not as publications but as “original art” displayed on walls. How did you arrive at this peculiar paradox? And why have none of the comic books been published as such?

There was a move afoot to publish my earlier Oist pieces, but I wanted to do all the color design, and never had a break from all the shows I’ve had to do to pay the bills. Now I’m doing a succession of four more Oist comics, and I also have an unfinished project to do all the comics I dreamt of that’s been long delayed. Fabrice Stroun [of JRP] would love to publish them, and so would I, but they are a difficult sell as art objects, since we’re talking about 20 pages sold together in a “debased” and disrespected medium. After seeing the Sistine Chapel and thinking how radical a piece of art it was and so wanting to work in the figurative, I realized that comics are one of the only art forms where the figure has any legitimate use, so I’m glad to be working in it, and I’ve finally graduated away from needing to use photo reference to draw them.

What do you mean “legitimate”? You yourself still make figurative paintings, as do some of your peers.

Maybe “only” and “legitimate” are overblown, but I do think that to do a painting of a figure posed ala the Sistine Chapel would be either ironic or pandering in the present, so maybe “unironic” could replace “legitimate.”

There’s some bitter irony here that you can make comics for the wall but not for publication. A twisted inverse of the pop paradigm. Is it different to stand and read “drawings” than to sit and read “comics”? Does your friend Robert Williams ever give you shit for this work?

I know that Ditko is adamantly opposed to comic art being shown on gallery walls, and that I get antsy trying to read a lot of text on the wall, and my ultimate goal is reproduction for any artwork I produce. I grew up experiencing art in books and magazines, and it’s still the main way I see stuff. Williams hasn’t given me any shit for doing comics, and I think he mostly gave up drawing them because his narrative urges were better expressed now in paintings. I’m glad to see him return in newer pieces to the inked line, something I was missing in the paintings.

Tell me about Billy as a protagonist. Who is he?

Billy is an amalgam of myself and my friends back in high school, but he’s basically a cypher for the American puritan pilgrim traveling through adolescence in the land of ’60s sin, drugs, beat-off material, rock’n roll, TV, etc.

One of the many compelling parts of My Mirage is its vision of visual culture as a place without high/low distinctions. That seems to mirror your own experience as an artist and collector. Is My Mirage an attempt of your own to create a lineage for yourself? Is it a kind of canon? And if so, have you been tempted to do a pure, explicitly curatorial project, or is that less interesting than synthesizing the work? I think here, for some reason, of “Faithful Cad”, which has the effect of working with both Jess and Gould — a neat doubling almost impossible without this kinda work.

Among my goals with the series was to effect a story through as many different media, aesthetics and types of storytelling as I could muster. There were a few pieces I knew I wanted to do from the beginning when I planned for about 100 pieces, all 14 x 17, that I always felt like I needed to do more research before I was ready to tackle. (Like I am now with The Book of O). This led me to have a number of further ideas, including a set of five videos (the Sinbad piece remains undone), so the series expanded to around 170 pieces. I was attempting a visual version of what Burroughs achieved in the cut-up method, but I would provide all the material that was to be cut up. I also tried to make the medium and the story match up in as many ways as possible, since this was my first big “novel”. So, a piece entitled “Watercolor” was a story about nearly drowning at the city pool, the water that trickled underneath the floors of the changing room, and the exposure to women’s pubic hair done in watercolor; or a piece in the style of Wes Wilson’s Fillmore posters, based on Munch’s Madonna, featuring Billy’s dream girl in that pose, which resembles Wilson’s earth mothers, and text from the lyrics to “I Heard Her Call My Name” by the Velvet Underground in place of the band names and performance details of a real Fillmore poster.

I’m fine with all sides of the culture. At the opening of the Kustom Kulture show there was a guy in a Big Daddy Roth outfit who would occasionally blast an

“a-ooga” type car horn, and it really did unsettle the high art types he was so obviously suspicious of, which is actually quite hard to do as our culture can coopt and absorb all kinds of rebellious activity.

“a-ooga” type car horn, and it really did unsettle the high art types he was so obviously suspicious of, which is actually quite hard to do as our culture can coopt and absorb all kinds of rebellious activity.

And was there ever a plan for the sources of My Mirage to be shown?

It would be really hard to encompass all the sources. Maybe I should do digital walk thru where I explain all the arcane references. It’ll be the same time as I do the color separations for the comic pieces.

Hippy culture has a profound impact on Billy and My Mirage — and you manage to suss out the raw power (pun intended) inherent in the imagery and correspondent lifestyle. What made it so intriguing to you (and Billy)? And did punk pass you by?

I was as close to a hippie that a middle class kid who lived at home in a small city in Michigan could be. My dream in ’67 was to move to Haight Ashbury and have my hair as close to Hendrix as I could get it. The problem began with Woodstock, where the same people who were spitting at me a year earlier were wanting get in on the perceived sex drugs and hedonistic lifestyle they imagined us to have achieved (nobody got laid in those days). I didn’t become a hippie to have the whole world join in, but to make plain that I was a weirdo. My friends all revered Zappa and we retained the cynical attitude of the first hippies (the cynics were rebellious youths in ancient Athens who acted like dogs and mocked society). Manson came along and made a mockery of the rhetoric of hippiedom, Nixon was president, we were all punks with long hair. Moving to Ann Arbor reinforced my resistance to the peace and love thing, as we had on one hand gnarly street people (i.e. crazy homeless people), and nascent yuppies on the other pursuing the hedonistic end of it all, listening to Dan Hicks instead of the Charlatans, smoking pot and building resumes.

The choice to tell Billy’s story via the media that engulfs him and transforms him (and which you in turn transformed) is very much a late 20th century move. It seems like you’re both celebrating the daily onslaught and warning against it. Or both. What are the ups and downs for you?

When I was a kid, I’d do my homework and listen to music, something unimaginable to me today. My own daughter becomes a zombie when the TV is on, and was so addicted to tweener sitcoms that we had to get rid of our cable. Unfortunately she just discovered digital downloading via her WII. The media today is a million times as enveloping as it was in the ’60s. TV was small, black and white and fuzzy: McCluhan’s cool medium. Today there are several 24-hour kid’s networks in high def, way more actually watchable shows, and stuff that panders to every interest group (except maybe artists). Video games activate the brain like a pinball game on steroids. Kids who act up in class will be force fed ADD drugs; how could you emerge unscathed from all that? Back in the 1800s the Bible was the main frame of reference and one’s attention was not taken away by any mechanical medium, unless they had player pianos in those days. That’s one of the elements I was contemplating in My Mirage: how rock ‘n roll replaced the Bible as a moral point of reference for most of us in mainstream America, a country that was largely like Afghanistan 60 years earlier.

Hmm, how puritan do you think America was? Did you consciously fight against nostalgia and easy ironies — you avoid both at every turn, so I wondered how much of a struggle it was. Do you mind nostalgia?

I am still listening to music from my youth (which ended with post-punk sometime in the early ’8os, apparently), as well as stuff from the ’20s, ’30s, ’40s, ’50s, etc. I don’t know how much of it is nostalgia, but I was eager to get My Mirage up and running as I knew it was inevitable that there would be a ’60s revival someday. I started coming up with the concept and researching around 1980, and first exhibited stuff in 1986. I’d been working in special effects at companies like Midocean and Robert Abel’s doing glitzy ’70s-’8os TV commercial effects (will Mad Men ever reach that coke-addled era?) and I had an older girlfriend who’d started as a beatnik (her high school boyfriend took her to the EC offices about the time they’d collapsed) who encouraged me to retain some of the positive aspects of the ’60s rather than trashing the whole era, and my researches began. I also began finding out about the utopian Christian communes of the burnt over district in the 1820s, and later that inspired the background of Oism.

I don’t know anything about these communes…

There were a number of Christian and other communes, many in the upstate New York and northwest Pennsylvania area, the west coast of it’s time. The first was called The Woman in the Wilderness, after a figure from Revelations. There was a community on Keuka Lake called New Jerusalem that I found out later was renamed Branchport and was a short walk from my grandfather’s cottage. It was fronted by a woman who called herself The Universal Public Friend, and claimed to be the reincarnation of Jesus, and whose death was hidden from the followers by her lieutenant/boyfriend. Mormonism was founded to the east of Rochester, to the west was the Oneida, a “Free Love” community that lives on today as the silverware manufacturer. The Shakers, started in England ended up nearby. Feminism, spiritualism, and the abolitionist movement were spearheaded in the region. Further afield in Iowa was the Amana colony, where microwaves eventually emerged from the ether. In Oism I appended elements of anti-slavery, feminism and theosophy to the brew in Annie OWooten’s head as she channeled the book of Oism.

Aren’t you going to ask me about comic books?

Oh, sure. Let’s go. Who is your favorite inker? Who do you like most for narrative flow? Did you ever find much to latch onto in underground comics, or were ’50s and ’60s SF and Superhero stuff freaky enough? What is your favorite Wally Wood period, and why? Wayne Boring or Curt Swan? What comic book do you most wish existed that does not, as drawn by a real and beloved artist?

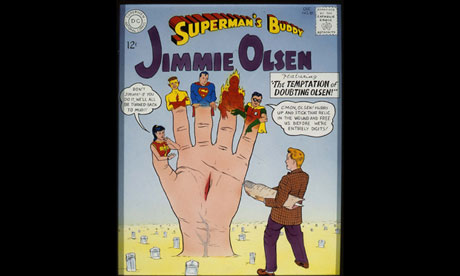

My family has always had a too-strong loyalty streak and as a kid I began with DC Comics, since Marvel was at the time just a step up from Charlton with its monster comics and murky colors. So I stuck with DC, having graduated from the more primitive comics — Superman and Batman — to the more “sophisticated” (their heroes were all scientists), Flash, Green Lantern, Atom, Hawkman, Adam Strange. So Murphy Anderson inking Carmine Infantino was my favorite. I realized the imagination at Marvel was far superior as their superhero comics began to appear, and I obviously valued Dr. Strange as the pinnacle of comic creation at the time. Now, I have a perverse fondness for the creaky DC plots, predicated as they were on startling, surreal cover images explained by insanely rational plots which often hinged on some scientific fact, like a chemical reaction.

Over time I saw more of the EC work, and Wally Wood was a presence through Mad and reprints- his women defined my ideas of attractiveness even before I saw Playboy (kinda sad, huh?). Of the EC artists, I think Johnny Craig had the best combo of drawing and storytelling, while Kurtzman was obviously the best at sequencial narrative. Now that the world of reprints is gearing up, I can see that I was missing out on the best work of Bob Powell and Bill Everett. It seems that the code wiped away the best instincts of many artists, and it seems from their bios, many were alcoholics whose talents would dissolve away as they might have grown. And then there’s Herbie and Katy Keene and all the odd things comics in their mindless production can create almost by accident.

Kirby did his best work in the ’70s after 30-40 years of comics. This gives me some hope as I approach 60 myself. Wood did great work at many periods… It was revealing to me to see his and Craig’s early comics, as five years in the trenches made them much better artists, they didn’t just pop out of the womb as masters.

Wayne Boring’s work has a sad poetry to it. The way he drew Superman as a stolid middle aged guy with a wide trunk, the many stories of tragic lost loves, and then to realize he was paid by DC to essentially change the look of Superman since they were being sued by his creators at the time. Curt Swan was obviously a superior artist at drawing realistic faces and expressions, but then he represented the pinnacle of the corporatization of the line, of the lack of vividness, culminating in the company’s absorption by Warner Brothers. In researching Boring I found some caricatures he did of his old boss at DC and they were quite good, showing an ability at humor that almost never got an outlet in Superman.

The undergrounds were a continuation of my love of comics, and a bit of an enabler to maintain a childish interest past childhood. The Zap artists and Binky Brown are to me the best of the lot, no surprise. R. Crumb , after starting the whole thing, is still going strong. His Book of Genesis is very good, but it means I can’t pursue my idea of doing a comic version of the book of revelations. Let’s not forget Chester Brown and Dan Clowes and Alan Moore and I’m sure there are lots of other post-underground comics that I don’t have time to read.

Artist Jim Shaw stuffs American pop culture through the Rinse Cycle

From a giant eyeball to a venomous version of the stars and stripes, Shaw's first UK retrospective is eye-popping in its scope – but just a bit childish, finds Adrian Searle

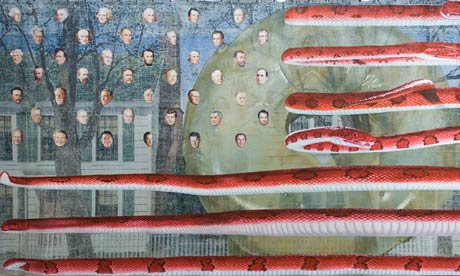

Flag gag ... Jim Shaw's Untitled, US Presidents (2006). Photograph: Colin Davison

Small-town America, with white picket fences, frame houses and bare winter trees. This faded image of a faded time is painted on a vast theatrical backdrop from the 1920s or 30s, one of several found and worked over by Jim Shaw, and now on show at the Baltic in Gateshead.

Take his homely version of the American flag. Painted portraits of the first 43 US presidents float like stars over the ghostly view of apple-pie America, while the stripes are red cane snakes with flicking tails, their heads turned malevolently towards the viewer. George W Bush is there among the stars, with Tricky Dicky, JFK, Reagan – all the presidents right back to George Washington. (Painted in 2006, the Republicans had yet to be ousted by Barack Obama.) Sandwiched between the heads and snakes and houses is a big doughnut, like a globby orifice, a spiritual void opening up in the middle. Why does Shaw always have to spoil things, take it too far?

Going too far is what he does: his projects take him years, driving him – and us – to peculiar places. This retrospective, the artist's first in Britain, goes a long way too, though Shaw's best-known project – his amateur art collection accrued over decades in junk shops – is not included. The show and accompanying book of Shaw's Thrift Store Paintings spawned a market for the hapless and the abject, the sentimental and crazy. He knew how to pick them, and had a great eye for the worst kind of art. But was it the worst, or just a flip-side version of the approved inanities of contemporary art?

Comic-strip tease ... Jim Shaw's The Temptation of Doubting Olsen (1990). Photograph courtesy of the artist and Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York

Comic-strip tease ... Jim Shaw's The Temptation of Doubting Olsen (1990). Photograph courtesy of the artist and Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York

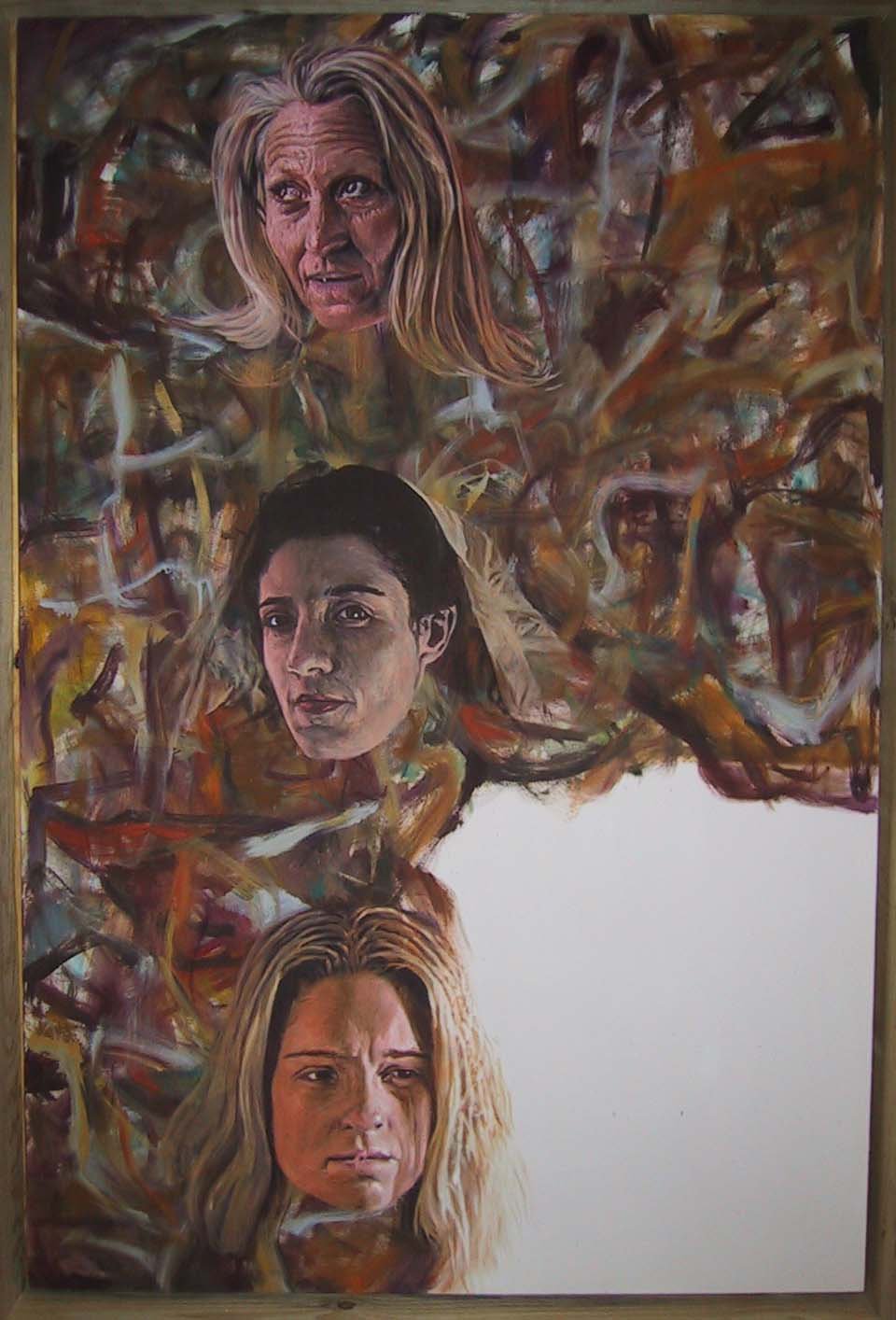

Shaw's frontier spirit leads him on, even into the nether regions of his own autobiography. My Mirage, a series of drawings, paintings and text pieces from 1986-91, tells the story of Shaw's alter ego Billy via spoof comic-book pages, versions of Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are and Grateful Dead album art. Magritte and Tom of Finland are in there too, with literary parodies of William Burroughs and Ian Fleming (a page from a James Bond novel called Manlicker), all done at a high level of pastiche.

Billy does drugs, sex, cults – the whole panoply of far-out American life – and finds redemption in religion of a sort. It is a very American story, told with wit and terrifying leaps in style and layers of complexity (it's like early Thomas Pynchon in its sweep).

Shaw's later works purporting to come from his dreams don't have quite the same bite, and there are many things in his art I don't much care for. But don't blame the artist, blame the world – for stoner ramblings, zombies and mormons and freemasons, acid rock and Christian pop, heavy metal and lamentable 70s prog-rock concept albums. It all finds a place in Shaw's cosmography, alongside faux abstract expressionism, TVs with gigantic eyeballs bursting from them, massive humanoids sculpted from free McDonalds toys, and vacuum cleaners with so many hose attachments they look like the multi-armed god Shiva. What about bagpipes? Bagpipes would be bad enough, but Shaw has used a child-size coffin for the bellows – one of several self-invented musical instruments to his name.

Eye-opener ... Jim Shaw's Dream Object (Eyeball TV Model) 2006. Photograph courtesy the artist and Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York

Eye-opener ... Jim Shaw's Dream Object (Eyeball TV Model) 2006. Photograph courtesy the artist and Marc Jancou Contemporary, New York

Both adept and arcane, the 60-year-old artist has no consistent style. He is aware of the pitfalls of a fixed approach – all those artists who get better and better at less and less, falling from favour as fashions change. Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of his later projects has been to invent a religion. If it's good enough for Joseph Smith, inventor of the Mormons, or L Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, why not Jim Shaw, artist and only begetter of Oism, a religion no less plausible than any other? He's certainly not the first artist to tinker with the spirit, he just goes further than most. A wish to spare the reader, and myself, prevents me from elucidating further on Oism. "Why not," as one writer in Shaw's catalogue says, "create a new religion, one specific not only to Jim Shaw, but also to pop culture and the art world particularly?" Why not indeed. Move over Rothko, move over William Blake, move over Joseph Beuys. Here come Shaw's Oist women in gauzy nighties, dancing round a banyan tree in a swirling high-production video.

McDonald's magic ... Heap (2005) by Jim Shaw. Photograph: Colin Davison

McDonald's magic ... Heap (2005) by Jim Shaw. Photograph: Colin Davison

Somehow, it's all very male and sniggery, despite Shaw's artistic erudition. Like the late Jason Rhoades and Mike Kelley (Shaw was a founder, with Kelley, of the band Destroy All Monsters), like Paul McCarthy and Britain's Jake and Dinos Chapman, there is in his work a constant return to artistic adolescence. It's a nerdy boy thing. If, for all his serious subjects, Shaw is a funster, he's one of those CalArts graduatefunsters whose art is a cargo of complex obsessions. I struggle with many of his popular and unpopular cultural references, but then I guess many American viewers would have similar problems with the art of Mark Wallinger (Who is Tommy Cooper? What is a tardis?).

A giant octopus floats by, head down, dangling like a testicle. There's a lot to be getting on with in Shaw's copious oeuvre, but only so much I can take in a single visit. This is a show to come back to, just like the America that forms his central, complicated subject. Avoid the void and pass the doughnuts.

The Annotated Artwork: ‘The Donner Party’

Where Mormons meet feminists over a scary, scary meal.

|

(Photo: Courtesy of Magasin-Centre National D'Art Contemporain, Grenoble/P.S. 1)

|

What do maimed appliances, mutilated Barbies, Mormons, cannibals, feminists, and Mr. Magoo have in common? Jim Shaw’s 2003 installation The Donner Party, on view at P.S.1 starting May 24, takes its name from the infamous group of flesh-eating pioneers, its form from Judy Chicago’s much-analyzed work The Dinner Party, and its philosophy from “O-ism”—Shaw’s made-up feminist-meets-Mormon religion of which we’d imagine Big Love’s Margene (wife No. 3) at the helm. Is this history rewritten? Perverse arts and crafts? Some sort of attack on Chicago? We asked Shaw to explain.

1. The Concept

“It’s not really a satire,” says Shaw. “The idea came from switching the i in The Dinner Partyto o. O-ism is the feminist version of Mormonism. Its symbolic animals would be orangutans and octopi. I’m pretending that the Donner party would have converted to O-ism and headed west to find the promised land: Omaha. It starts with an O and it’s halfway west. Besides, Omaha has really good thrift stores,” the source of many of the work’s materials. “I’m also working on film elements like an O-ist exercise tape.”

2. The Wagons

“We designed them without a computer. We ordered a bunch of wheels from an Amish wheelwright over the Internet—of course, they have to have a non-Amish person to do the Internet selling. The circling, which forms the table itself, is something you’d do when you’re surrounded by Native Americans. It’s meant to be a stereotype of the Old West, but also forms a perfect self-enclosed unit.”

3. The Place Settings

To create them, the artist enlisted nineteen students and colleagues. Each chose a name connected to O-ism (Yoko Ono, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Mormonism founder Joseph Smith) and a few of Shaw’s thrift-store finds and household appliances. “[The result] was sort of childlike, and not as varied as I had hoped,” he says. “It’s supposed to be about a situation that got out of control, like the Donner party, and that’s an aspect that got out of my control.” As for the collective effort, “The Dinner Party was criticized for Chicago’s alleged exploitation of her collaborators. Up until this project, I had a hard time collaborating, so it was in part about that, but also the notion of artistic cannibalism.”

4. The Vacuum Cleaner

At the center of the circle is a vacuum, which Shaw says “sucks into itself. I was thinking about the way in which art inevitably stamps what comes after it. It’s on the ruins of a campfire, surrounded by wrapped pieces of meat representing the different artists who are being cannibalized, like Jackson Pollock and Judy Chicago. [Members of] the Donner party didn’t want to eat their own relatives, so they wrapped the meat up and labeled it.”

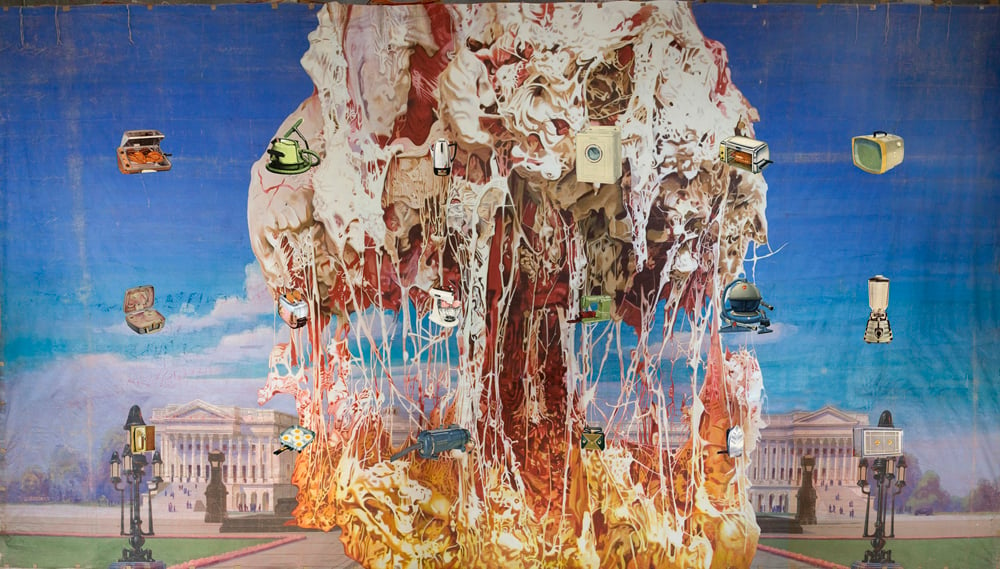

5. The Canvas Backdrop

“It’s set against the landscape of the Sierra Nevada. It gives the work a presentation similar to the Mormon visitor center in Salt Lake City. The figures are supposed to be confusing: feminist artist Lynda Benglis; actress Tina Louise as the anti-O, the whore of Babylon; Mr. Magoo as Bacchus; Loki; L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology. They were painted by many different people who had many different styles, so there was supposed to be an element of chaos. It wasn’t as chaotic as I wanted it to be.”

Jim Shaw, Cake (Blake), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Painting: 37-1/2” x 37-1/2” (95.3 x 95.3 cm) = 1,406

.jpg)

Jim Shaw, Cake (Blake), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Panel: 22” x 10” (55.9 x 25.4 cm)

Jim Shaw: Cakes, Men In Pain, White Rectangles, Devil in the Details

Patrick Painter, Los Angeles

2525 Michigan Ave, Unit B2

Santa Monica, CA 90404

May 6 through June 17, 2011

Patrick Painter, Los Angeles

2525 Michigan Ave, Unit B2

Santa Monica, CA 90404

May 6 through June 17, 2011

Jim Shaw suffers from “monumentality,” having created an incredibly boisterous, all-encompassing, mind-bending, hell-raising, alternately tender and fierce group of epic paintings in his most recent exhibition entitled Cakes, Men In Pain, White Rectangles, Devil in the Details.

Working with several different ideas at once, Shaw has managed to combine important disparate elements, the first being an ink jet print taken from vintage ‘50s household magazines depicting decadent images of cakes. Shaw uses oil paint to, as he puts it, “overlay the images, using an Abstract Expressionist trope;” and the third element involves Shaw’s fascination with the medical illustrations of Dr. Frank Netter, which portray, again quoting Shaw, “the intersection of the physiological and psychological experience of pain with the individual’s physical response.” Imagine the fascinating shock of a man sitting down at an upscale restaurant for what he thinks will be a groundbreaking interview with a prestigious international magazine, only to find himself burned alive with a blowtorch.

The power inherent in these paintings derives from Shaw’s unflinchingly humorous self-analysis, as he frequently uses his own body as a subject. In the compelling panel Jim, (Anger, Frustration), Shaw shutters and grimaces even as his belly grossly protrudes into the picture plane. The image is seductive, too, as Shaw’s grotesqueries transform into an amalgam of deliberate theatrical misfires. Each of these panels is “missing” a piece of itself, Shaw having excised their central units and placed derivations therefrom alongside, which frankly read more like acts of hysteria than explanations. The overall effect of these paintings is well-fashioned and ribald humor on the edge of madness.

Working with several different ideas at once, Shaw has managed to combine important disparate elements, the first being an ink jet print taken from vintage ‘50s household magazines depicting decadent images of cakes. Shaw uses oil paint to, as he puts it, “overlay the images, using an Abstract Expressionist trope;” and the third element involves Shaw’s fascination with the medical illustrations of Dr. Frank Netter, which portray, again quoting Shaw, “the intersection of the physiological and psychological experience of pain with the individual’s physical response.” Imagine the fascinating shock of a man sitting down at an upscale restaurant for what he thinks will be a groundbreaking interview with a prestigious international magazine, only to find himself burned alive with a blowtorch.

The power inherent in these paintings derives from Shaw’s unflinchingly humorous self-analysis, as he frequently uses his own body as a subject. In the compelling panel Jim, (Anger, Frustration), Shaw shutters and grimaces even as his belly grossly protrudes into the picture plane. The image is seductive, too, as Shaw’s grotesqueries transform into an amalgam of deliberate theatrical misfires. Each of these panels is “missing” a piece of itself, Shaw having excised their central units and placed derivations therefrom alongside, which frankly read more like acts of hysteria than explanations. The overall effect of these paintings is well-fashioned and ribald humor on the edge of madness.

Jim Shaw, Cake (Daniel), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Painting: 37-1/2” x 40” (95.3 x 101.6 cm) = 1,500

Jim Shaw, Cake (Daniel), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Panel: 19-1/2” x 10” (49.5 x 25.4 cm)

Jim Shaw, Cake (Daniel), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Painting: 43-3/4” x 39” (111 x 99 cm) = 1,706

Jim Shaw, Cake (Daniel), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Panel: 16” x 13-1/16” (40.6 x 33 cm)

Jim Shaw, Cake (Blue Jim), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Painting: 37-1/2” x 51” (95.3 x 129.5 cm) = 1,912.

Jim Shaw, Cake (Blue Jim), 2011

Oil on digital ink jet print and acrylic & ink on panel

Panel: 14” x 14” (35.6 x 35.6 cm)

- Eve Wood whitehotmagazine.com/

Jim Shaw, Dreams

Softcover, 288 pp., offset 1/1, 6 x 8 inches

Edition of 2000

ISBN 978-0-9646426-0-7

Published by Smart Art Press

Softcover, 288 pp., offset 1/1, 6 x 8 inches

Edition of 2000

ISBN 978-0-9646426-0-7

Published by Smart Art Press

Most people consider their dreams private property — too personal, too scary, and too weird to share — but not internationally renowned Los Angeles artist Jim Shaw. In Dreams, a monumental compendium of painstaking pencil drawings that bring his nocturnal dream world to life, the artist unflinchingly reveals his innermost fears, obsessions, and sexual fantasies. A diarylike picture book, Dreams is an in-depth look at one of the most important facets of this seminal artist’s work.

Jim Shaw, Everything Must Go

Softcover, 150 pp., offset 4/1, 8.25 x 10 inches

English and French

Edition of 2000

ISBN 2-919893-23-8

Published by Smart Art Press

Softcover, 150 pp., offset 4/1, 8.25 x 10 inches

English and French

Edition of 2000

ISBN 2-919893-23-8

Published by Smart Art Press

A survey of his career from 1974 to the present, Everything Must Go is the first catalogue to incorporate the full range of Jim Shaw’s profoundly original and idiosyncratic work. From the massive 170-piece multimedia work My Mirage to his Thrift Store Paintings, Dream Drawings, and Dream Objects, Shaw has created a fantastic visual narrative that references diverse outside sources, moments of personal history, and fragments of our collective cultural consciousness. His highly individualized “outsider” perspective has established Shaw as a seminal figure in Europe and the United States, and he has contributed significantly to the influence of Los Angeles in the international art community. Essays by Amy Gerstler, Doug Harvey, Mike Kelley, Noëllie Roussel, and Fabrice Stroun.

by

Hawk & Shaw

It’s been a crazy year for Jim Shaw. In January, having drastically downsized his legendary atelier community in the wake of the economic crash, he moved out of the studio that had produced some of Los Angeles’s most ambitious and monumental artworks of the past decade. He took the opportunity to deaccession much of his equally legendary hoard of pop-cultural ephemera — we’re talking tons of pocketbooks, vinyl LPs, vintage magazines, religious pamphlets, board games, collectible figurines, and so on — much of which had served as source material for his feverish postmodern appropriations. Two days later, the body of his longtime art comrade (and collaborator in the seminal noise band Destroy All Monsters), Mike Kelley, was discovered, an apparent suicide that the L.A. art world has not yet fully digested. So much for clearing the decks.

Named an executor of Kelley’s estate, and the only artist on the board of the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, Shaw found himself enmeshed in the minutiae of his good friend’s legacy when he was supposed to be not only producing new work for solo exhibitions at Metro Pictures, Simon Lee, and his new L.A. dealer, Blum & Poe, but also sorting out the particulars for a large-scale midcareer survey that opens November 9 and runs through February 17 at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, in Gateshead, England, where last year’s Turner Prize exhibition was held. I caught up with Shaw in the midst of his hectic schedule at his new, streamlined work space, sandwiched between a liquor store and a beauty salon in a strip mall in Altadena, a few minutes northeast of downtown L.A., and asked him how Kelley’s death had affected him. He declined to go into detail about his legal responsibilities but was forthcoming about the personal impact.

“One thing it’s done is make me realize that for a lot of my life as an artist, I’ve looked at the people that came before me and thought they were really good, but they made this mistake, and I don’t want to make it,” he says, glancing up from daubing paint on one of his signature torn-photorealist portraits. “Of course, I made other mistakes, but — looking at Mike and what he achieved…he achieved a lot, but he paid a huge price for it, and I don’t want to pay that price. I don’t want to continue to kill myself to make this art and let the rest of my life go down the tubes."

“It’s made me less materialistic, too, looking at Mike’s library, his fabulous library, then looking at my fabulous collection of crap. I was already getting rid of it at the time because I had to move out of that studio. But now I’m even more like — if I read a book, I’m not going to keep it forever; I’m going to recirculate it. I’ll just keep the ones that have reference material that I need to keep going back to. That’s why I don’t want to get caught up in making the prog-rock opera if it means going into debt. I’ll keep it as an ideal, but it may never get completed.”

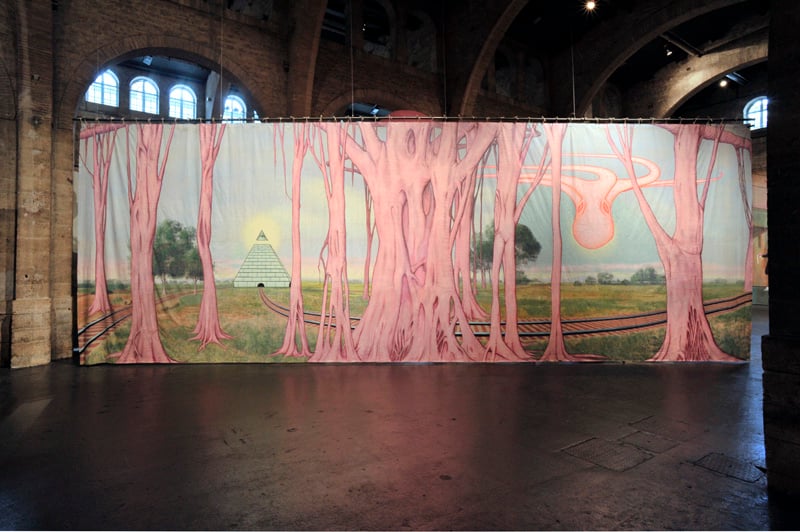

Yes, you read that right: Prog. Rock. Opera. The crowning Gesamtkunstwerk in Shaw’s long-term project exploring the mythological, historical, and cultural manifestations of a fictive 19th-century new American religion called Oism, the long-rumored multimedia extravaganza was gearing up to full production mode in 2008 when the Wall Street apocalypse struck. The originally envisioned debut of the work at the CAPC in Bordeaux morphed into the acclaimed “Left Behind” exhibition there, dominated by Shaw’s ridiculously complex allegorical paintings on gigantic found theatrical backdrops, predicated, at least in part, on an inspired associative leap equating the fundamentalist Christian rapture with the plight of the American working class — a curiously topical leitmotif that seemed to have been lurking in the material all along...

Read the rest of Mad World: Jim Shaw’s Wondrous and Difficult Yearat the ArtInfo site or in the November print issue of Modern Painters

Jim Shaw: The Rinse Cycle & You Think You Own Your Stuff But Your Stuff Owns You (Thrift Store Paintings)

9 November 2012 - 17 February 2013

Baltic Centre For Contemporary Art

Gateshead Quays, South Shore Road

Gateshead NE8 3BA, UK

I would also like to draw your attention to this article in the NYTimes about the insane treehouse Tim Hawkinson built for his daughter Clare, which was an piece I wanted to write, but Carol Kino beat me to the punch...

Images: Jim Shaw; Mall Culture (from Strange Früt: Rock Apocryphadesigned by Shaw & Mike Kelley for DAM); Shaw in his new L.A. studio; The Rinse Cycle 2011, acrylic on muslin; Untitled 2008;Capitol Viscera Appliances 2011, acrylic on muslin.

Shaw portrait photos by Kevin Scanlon; Clare’s treehouse photo by Tierney Gearon

Jim Shaw works in Glendale amongst machine shops and mechanics garages, not too far from a large number of car dealerships. Shaw’s studio is non-descript among them except that it is filled full of piles and piles of projects, assorted paintings and papers, severed movie prop Satan heads and all sorts of ephemera. He has always worked this way, deploying a number of styles, as likely to do a painstaking super-realistic drawing as he is to do a sculpture of a Ganesha with his own head perched atop. I found Shaw at his easel for a painting destined for Art Basel, one of a series he started a few years back mixing painting what he calls “his best attempt at Abstract Expressionism” with a floating head hovering on the surface, which Shaw paints in pieces from ripped photographs. The head today was a Zombie, and Shaw himself was quiet.

“I guess you are going to ask me questions,” he said quietly, looking intensely through two sets of eyeglasses worn together, “These paintings are sort of my art market suicide net, but the irony is that they ended up being one of my most popular series ever.”

I stayed relatively quiet and just let Shaw talk, and talk he did, scanning topics from Rudolf Steiner Waldorf schools to progressive rock operas to anxiety over what he feels is the troubling legacy of Reagan’s vision of America. He talked up his upbringing in Michigan, the house he recently purchased there, and his sympathies with the plight of Detroit. A flashpoint of all these topics was his description of his upcoming show in Bordeaux, France, a series of theatrical backdrops that he did years back and felt obliged to show. He casually calls them the ‘left behind paintings.’

“The backdrops have much to do with political considerations, especially with how things changed under the Reagan and Bush years. Basically, they respond to a change in philosophy from ‘if you work hard, you’ll succeed’ to ‘if you gamble well, you might succeed.’ I think about what I call the great siege of Detroit, or that’s what I call it, which I consider to be sort of the last battle of the civil war. I feel that the country could have saved Detroit. Maybe it’s the right wing’s revenge, the price we paid for free trade and globalization. In the civil war, the south was left in tatters and now the same thing is happening in the north with supplanting of labor for free trade. Detroit falls into ruin.”

Shaw wears his Michigan history and talks of the decline of unions and the plight of American industry. All of this, according to Shaw, is closely connected to the popular culture that America produces, its emphasis on religion, even America’s taste for the apocalypse.

“Americans are obsessed with the book of revelation,” Shaw related in a deap-pan monotone, “People, I think ultimately, don’t want to live forever, struggling and working their butts off. I was raised Episcopalian and that doesn’t really count. I remember the preacher told us sermons based on Peanut comics. Religion always lurks in the background of society. Even though people try to be un-materialistic, you are always brought down to the physical world. I send my daughter to a Rudolf Steiner school, but it is hard to co-exist in a capitalistic world without being slightly capitalist.”

Shaw is so interested in religion’s influence on culture and its structures that he has been working for a number of years on a religion of his own, called O-ism.

“In 1993, I started working on my own religion, which I call O-ism. It is a basically a religion rooted in its American founding. O-ism is based on Mormonism and Scientiology, it is an American based religion. It is basically founded by a feminist in upstate New York, a place which has been the basis of other cults like the Universal Friends, that were founded near Kueka lake, this area that is even more depressed than Detroit. At the height of the Eerie canal, this area was like California, it was popular. O-ism, founded there in my history, eventually loses its roots, becoming less feminist and more corporate, starts out at anti-materialism but slowly gets more and more materialistic. It is long slog for new ideas, I want to work on its pre-history, its mythologies.”

When I asked how religion plays into the Bordeaux work, he spoke again of the “left behind” series of works and how they will be presented:

“Alongside the backdrops, I will display my archive of old Christian artifacts and I think that they relate to the ‘left behind’ paintings, to how people cling to religion when labor and American power starts to slip. The archive is the pop of the Christian Right and is related to the Reagan revolution. These objects were never hip and are still not hip, and I have no trouble winning any of this stuff on Ebay. The backdrops are related to the decimation of Detroit or Chicago. The back drops are kind of a Roger Deanish world. He did all the Yes album covers.”

The Bordeaux show, it seems, is one result of a yet unrealized project of Shaw. He loves music and often performs with his studio band as well as “about once every five years” with Destroy All Monsters, his band with Mike Kelley and Cary Loren. His dream is to complete a progressive rock opera.

“The prog rock opera that I want to work on is related to the imagery on those Yes Album covers. The prog rock opera might turn out to be an interesting failure, but I am sometimes interested in how a creative process can go wrong. My original intention with the Bordeaux show was to present the musical and new work, but I am showing these backdrops. With the Glenn Beckification of the world these days led me to conclude that these political works are not in vain. I would love to be doing my prog rock opera, but I am not Steve Howe. I look to Sun Ra and Captain Beefheart as what I would do if I was a musician, bring diverse lives into the work.”

Shaw is most known for, perhaps, his dream drawings, a series of works that he began in the early nineties, documenting visually the content of his dreams. I did not want the interview to end without asking about this work and its relation to Surrealism, to writers and painters that supposedly dealt with dreams in the first half of the 20th century.

“Surrealism was primarily a literary phenomenon, and it was involved with accessing the unconscious rather than with the specifics of dreams. The writers came first and the artists came later. When the visual artists worked with the idea of dreams, it was not the specifics of their own dreams, the work was more like political cartoons, Dali for example. They seemed dreamlike but weren’t. My work involves the specifics of my dreams, usually steeped in popular culture. I used to tape record my dreams, speak out loud about what they were about, because I found when you write them out, they often disappear as you write. With the dreams, I try to work in a direct conscious way, a combination between the subconscious and visual conjunctions, the works are like visual puns, the visual provided different puns than writing can. For instance, the D.C. character Flash often appears in my dreams, and I figure that he is essentially the Mercury or the devil in red, he is like an amoral version of the devil.”

Shaw is a workaholic and his work seems to flow from all angles of his life, and Shaw does not seem capable or interested in having a body of work separate from the background and content of his life. The ramshackle confluence of dreams perhaps sums up his practice well. Shaw, however, does admit that his multiple styles and hodgepodge approach is not the norm and perhaps antithetical to much of the artworld, and he is definitely inclined to talk about this fact.

“Most artists are concerned with singular ideas and singular works. I don’t want a Big Mac approach, I don’t want a particular Jim Shaw style. If I get comfortable, I move on. A Big Mac approach is a style that is recognizable, the work by which you will be remembered, it behooves you to present yourself in this way. For instance, ‘I am the guy that photographs shoes.’ You are taught that you shouldn’t have variety. I never really had a look and always made too much work. I guess that I just can’t stop, and I think that is my way of dealing with the Big Mac method, my method is dealing with the method of having a Big Mac approach.”

- flaunt.com/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar