Majka svima poznatog Nicka Drakea, Molly Drake, '50-ih je u obiteljskoj dnevnoj sobi, klečeći na Nickovim leđima, snimala ove pjesme, no tek su sada i objavljene. Uz ovakvu majku vrijedi malo i patiti.

streaming

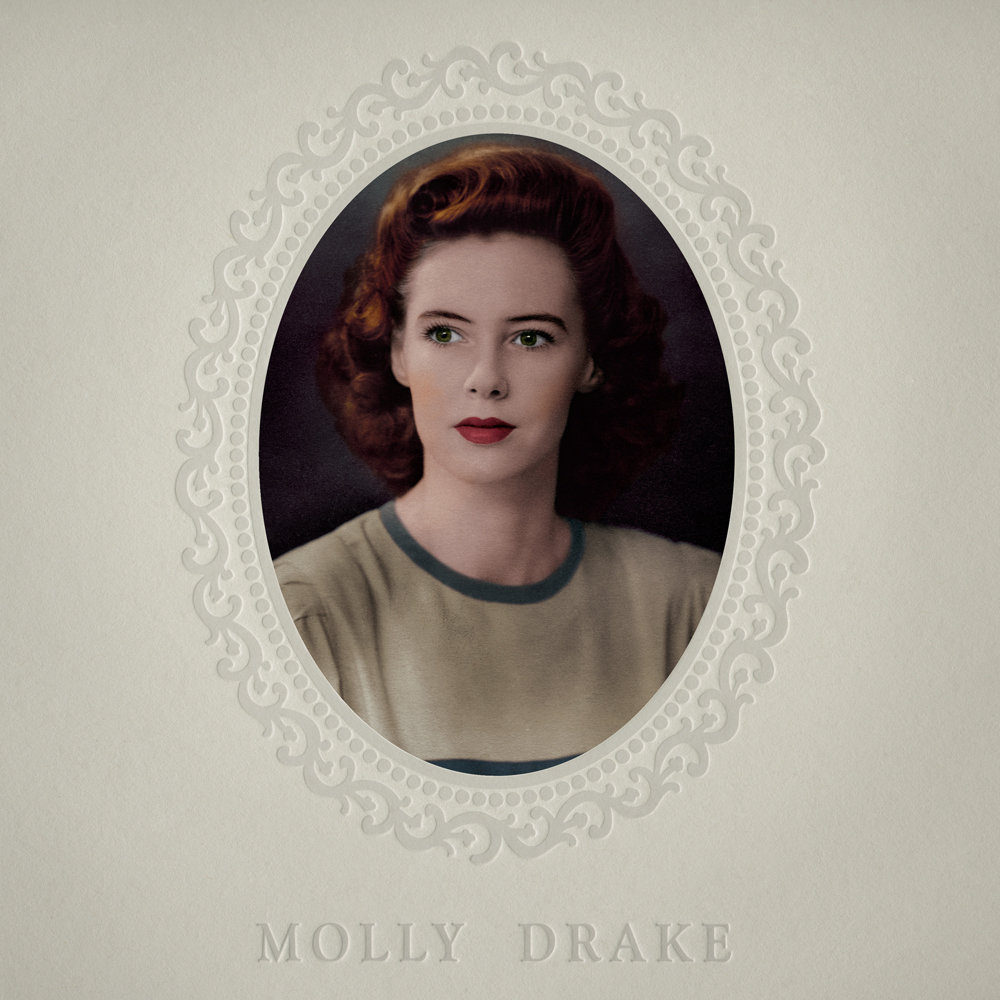

Squirrel Thing Recordings, the label behind the mysterious lost recordings of Connie Converse, is proud to announce the release of Molly Drake—a self-titled collection of never-before-heard songs recorded in the 1950’s at the Drake family home, and lovingly restored by Nick Drake’s engineer John Wood. According to Joe Boyd, legendary producer of Five Leaves Left and Bryter Later, “this is the missing link in the Nick Drake story.”

Molly Drake is a comprehensive first look at a singular and sophisticated artist, whose influence on her son’s celebrated musical style is undeniable. The CD features a custom letterpressed jacket, family photos, and a biography by her daughter, Gabrielle Drake.

Much like her son, Molly Drake’s music is at once beautiful, charming, dark and pensive. The easy elegance of her lyrics belies their deeper themes of regret, memory, dread, and the sublime, crystallized as only a poet can. Her performances are intimately staged in the family sitting room, and perfectly complemented by her own piano accompaniment.

Nick Drake: in search of his mother, Molly

The collected songs of the legendary musician's mother offer a poignant insight into his early life and influences, as Nick's sister Gabrielle explains

Molly Drake … melancholy meditations on the fragility of happiness.

A dozen impeccably coutured sixtysomething women are sipping their cappuccinos in west London's Café Richoux, but only one of them isGabrielle Drake. The last time we met here, she had to rush from our interview to an audition for an acting role – a journey complicated by the fact that the sole of her shoe had just snapped in half. As she kept a taxi waiting, I found myself running around the Mayfair streets that Gabrielle's brother Nick once hymned on an eponymous early song, searching for superglue. In the event, glue was found, but it didn't dry in time. Gabrielle recalls that her limping entrance – "like an aged Cinderella" – provided "a good talking point" at the audition.

It's hard to pinpoint a moment when Nick Drake's cult status superseded that of Gabrielle, who for three years donned a purple wig for early 70s science-fiction TV series UFO. Even in 1985, more than a decade after he took his own life, most mentions of his name came in magazine interviews with Gabrielle, who – as Nicola Freeman – had just taken over at Crossroads motel. But if it bothers her that these days she is primarily known as "Nick's sister", there is no sign of it. Indeed, the care with which she chooses her words suggests that her protectiveness towards her brother is growing. Posthumous fame, she observes, comes at a price, "and even Nick's obstinate integrity couldn't have prevented it".

In the case of Nick Drake, one price of that fame has been the steady stream of bootleg albums – most of them unwittingly originating from his parents, Rodney and Molly Drake, who would proudly copy cassettes of home recordings for fans who made the pilgrimage to Far Leys, the house in Tanworth-In-Arden where the Drakes lived. Frustrated by the quality of the recordings being circulated, Gabrielle has sanctioned the release of two "rarities" albums. Almost all of 2004's Made To Love Magicwas known to collectors, but the real revelation came with the release of 2007's Family Tree. The record saw Nick's interpretations of folk guitar standards by Bert Jansch and Jackson C Frank interspersed among a handful of home recordings that predated Nick's three albums. The hope you have when listening to any music from the formative years of an iconic artist is that you might come to a greater understanding of their genius. Family Tree featured a couple of previously unheard songs that did just that – yet Nick was nowhere to be heard on them. The inclusion of two songs by Molly Drake bore an eerie testament to her influence, conscious or otherwise, on her son. When Nick Drake's producer and mentor Joe Boyd heard them, he declared that "this is the missing link in the Nick Drake story".

He wasn't wrong. Listening to Poor Mum and Do You Ever Remember? you realise that the component of Nick Drake's music that had eluded both his peers and every artist who cited him as an influence was so far removed from the 60s singer-songwriter milieu, that no one could have ever guessed it. But to listen to Molly's quintessentially English postwar blues was to be reminded that melancholy meditations on the fragile nature of human happiness are not the sole domain of sensitive young men with guitars. Indeed, it was a point she seemed to be grabbing at with one of her later songs. When she heard Poor Boy from her son's 1970 album Bryter Layter, she set about issuing a dry riposte in the form of her own Poor Mum. "Pack up that last little yearning," she sings to herself, "Pack it away with the books and the toys/Silent and dumb/Silent and mend."

"I don't think Nick even knew she wrote that song," smiles Gabrielle, whose resemblance to her mother is almost unnerving. "But, yes, she's saying: 'You've got those emotions. Well, I got 'em too actually. We're notjust sitting here in the background." Elsewhere, just as Nick Drake's Fruit Tree seemed to portend his own posthumous fame, Molly's Do You Ever Remember? – recorded roughly a decade before her son's fatal overdose – found her singing about loss with a prescient acuity: "Time can steal away happiness/But time can take away grief/So I won't try to remember/For that way leads to regret."

Rather than sating the intense curiosity in Nick Drake's music, the release of Family Tree merely served to intensify it. Except that, this time around, the focus of that curiosity, was the woman who brought him into the world. All of which explains the emergence of a CD of recordings by Molly Drake, accompanied by a booklet of her poetry. The lack of promotional fanfare – no ads or press releases, just a small notice buried on Nick Drake's website – has been deliberate. Gabrielle seems conscious of disappointing anyone who might come to these songs expecting "Nick-by-proxy." In fact, what makes Molly Drake's music fascinating is the very stuff that sets it apart it from her son's oeuvre.

Molly and Rodney Drake moved to Britain from colonial Burma (where Rodney worked as an engineer for the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation) but not before having to walk into India in 1942 on being told that the Japanese were about to invade. "Until then, life was fairly easy out east," recalls Gabrielle, "There were lots of servants … not that I remember having a spoilt childhood. Then suddenly we were back in England and in the grips of rationing. And yet, we were lucky in a way. We came back with my nanny who knew far more about England than mummy did. I remember the two of them standing over the Aga with a recipe book trying to work out how to roast beef, that sort of thing!"

Then, of course, there was the piano – here, as in so many upper middle class families of the time, the recreational hub of the house. And, in the case of Molly Drake, a trusty outlet for a side of her personality rarely revealed by her outwardly sunny disposition. On Happiness, she compares the subject of the song to a wild bird: "If you grab at him/Woe betide you/I know because I've tried." On Never Pine For The Old Love and Breakfast At Bradenham Woods, her mistrust of nostalgia seems to be a recurring theme. The latter sees her casting her mind back to a childhood day out, enjoying the memory, yet determined never to tarnish it by returning. "Mummy always believed there was nothing to be gained by going back," saye Gabrielle. "When my brother died, she always said about Far Leys: 'We must stay on until we've made it into a happy house again.'"

It's this resistance to anything that might resemble wallowing that firmly plants Molly Drake's outlook in a Britain where self-pity was considered as much a luxury as chocolate. A note, found in the leatherbound folder where she kept her poems, reads: "To me a poem is not a forever thing, nor the statement of long held views, but the product of a moment so suddenly and hurtingly felt that it has to burst out into words." Read on and you can see why she might have felt the need to set straight anyone who happened upon the contents. In its way, The Shell is as startling a piece of work as her son's bleakest recording, Black Eyed Dog: an address to the "outer desolation" we have to routinely deny in order to merely get through the day. It's a theme also addressed on The Two Worlds. Here, "only a strand, thin as a spider's web/Holds us above the final broadening crack" of some unspeakable abyss.

Molly Drake and Nick shopping.

Molly Drake and Nick shopping.

In another era, Molly might have turned her songwriting into a vocation. But in the 1940s, the numbers of educated upper middle-class women who held down "proper" jobs were few. Nevertheless, Gabrielle recalls that "shortly after our return from India, [Molly's] best friend's mother was publishing children's songs and asked mummy to put together a tape – well, a manuscript probably. I don't think she would have been unhappy for songs to be published." By the same token, it seems that neither was Molly Drake unhappy for the world to go on turning, oblivious to her existence. "Her creativity was a personal thing," says Gabrielle, "and she was lucky to be able to develop it in an environment where that side of her was totally accepted. Indeed, my father encouraged it. He was so proud of her. On one occasion, he even made the 20 mile drive to Birmingham to get four songs pressed onto a disc."

If the idea of someone writing and performing songs without seeking a public outlet for them seems strange to us, perhaps that says something about the times in which we live. "It was a more private era," concurs Gabrielle. "You look at people broadcasting what they had for breakfast on Twitter and the desire for friendship seems to have been supplanted by a need for saying what you are. That simply wasn't around in my mother's day." Perhaps that's why, to borrow her son's words, Molly Drake's songbook feels like a fascinating "remnant of something that's passed".

What, you wonder, would Molly, who died in 1993, make of all the posthumous attention? "I think she would have been surprised and gratified," ponders Gabrielle, "but above all, amused." And Nick? "That's harder to judge. He once said to her that her songs were 'so naive' – but I do believe age would have moderated his view. I'm reminded of the old Mark Twain line about having found one's father ignorant as a young man. How does it go? 'Now that I'm older, I'm surprised at how much he has learned in the intervening years!'"

It’s a family affair: Molly Drake, mother of Nick, gets an album release

Some people just have coolness in their genes. You know these people. They have Cool Moms. They have Cool Dads. They have the most coveted type of family: artsy parents who bought them Kraftwerk records and get drunk with their offspring on their own special recipe holiday cocktails. The natural response here is to hate and envy these families. But today, let’s take a moment to applaud them, and one English family in particular: the Drakes, of Nick Drake fame.

See, Nick Drake had a Cool Mom. Molly Drake was also a Hot Mom and a Creative Mom. (Some people, geez.) Her influence on Nick Drake’s career is evident in her soft and melancholy home recordings, which are now being released on Squirrel Thing Recordings. The self-titled collection of previously unreleased tracks was recorded at the Drake family home by Molly’s husband Rodney in the 1950s, and was restored by engineer John Wood for the CD release. (Wood also worked with Nick himself.) The album features family photos, a letter-pressed jacket, and a biography by daughter Gabrielle Drake. Available on March 5, you can also take a sneak peek at the Molly Drake Bandcamp page.

Most of us are familiar with the fragile music of Nick Drake, who for many, became a poster-child of isolation and despair. For few of us, however, are familiar with the music that Nick’s mother, Molly recorded in the 50s. I know I wasn’t. Now that I am, I am hungry to hear more. Here is the press release from the label:

Squirrel Thing Recordings, the label behind the mysterious lost recordings of Connie Converse, is proud to announce the release of Molly Drake—a self-titled collection of never-before-heard songs recorded in the 1950’s at the Drake family home, and lovingly restored by Nick Drake’s engineer John Wood. According to Joe Boyd, legendary producer of Five Leaves Left and Bryter Later, “this is the missing link in the Nick Drake story.”Molly Drake is a comprehensive first look at a singular and sophisticated artist, whose influence on her son’s celebrated musical style is undeniable. The CD features a custom letterpressed jacket, family photos, and a biography by her daughter, Gabrielle Drake.Much like her son, Molly Drake’s music is at once beautiful, charming, dark and pensive. The easy elegance of her lyrics belies their deeper themes of regret, memory, dread, and the sublime, crystallized as only a poet can. Her performances are intimately staged in the family sitting room, and perfectly complemented by her own piano accompaniment.

Listen to how beautiful this music is:

The Songs Of Molly Drake, Mother Of Nick Drake

Never-before-heard songs recorded in the '50s at the Drake family home. Hear "How Wild The Wind Blows."

Tuesday, March 05, 2013 - 02:00 PM

Joe Boyd, producer of 'Five Leaves Left,' calls these songs "the missing link" in the Nick Drake story. (Courtesy of Squirrel Thing Recordings)

Joe Boyd, producer of 'Five Leaves Left,' calls these songs "the missing link" in the Nick Drake story. (Courtesy of Squirrel Thing Recordings)

The mysterious English songwriter Nick Drake wasn't particularly well-known in his lifetime. But since his death in 1974, at age 26, he’s developed quite a cult following -- and influenced so many other musicians. Now, we’re hearing from someone who was a great influence on him -- his mom. A new album from Squirrel Thing Recordings collects the songs of Molly Drake, who was an artist in her own right.

The 19 songs included on Molly Drake were recorded to tape at the family home in the 1950s, and have been restored for this release by the engineer John Wood -- who was also engineer to Nick.

According to Gabriel Drake (daughter of Molly, and sister to Nick), "For Molly, music was a private joy, as was her poetry...and she would sit for hours alone at a piano, working out words and music. It never occurred to her that her work could be of interest to a wider audience." Now it certainly is -- particularly the haunting and beautiful “How Wild The Wind Blows."

I caught up with David Herman, a recording engineer, and co-founder of Squirrel Thing, for a bit more backstory. (Full disclosure: Herman is also an employee of WNYC).

How did you come across this material? What appealed to you about it?

Two of Molly's recordings (“Poor Mum” and “Do You Ever Remember?”) were included on the 2007 Nick Drake collection Family Tree, (they were also heard in the Nick Drake documentary A Skin Too Few). My partner at Squirrel Thing, Dan Dzula, and I first heard these around 2011, and we were immediately floored. Not only by the eerie similarity between her voice and her son's, but by the poetry in her lyrics, somehow sophisticated and naive at the same time. It was incredibly poignant stuff. So we got in touch with the Drake estate to see if there was more of her music to be heard, and lo and behold there was!

What was it like to first interact with the songs?

The recordings are so intimate, when I listened to them on headphones for the first time, I felt as if I were sitting right there in the Drake family living room, next to her husband Rodney fiddling with his tape recorder, listening to Molly play the piano for no one in particular. It was a totally immersive, instantly transportive experience, much like the experience of listening to the Connie Converse tapes. I suddenly found myself in another time and place, and in a very tangible way.

What, if anything, does it tell us about the work of Nick Drake?

The enduring mystery of the Nick Drake story is why his music didn’t catch on during his life. It’s as if he were born to the wrong time, like he came out of nowhere. I think these recordings show us that he didn’tcome out of nowhere – he had a profound influence right at home. The musical styles of mother and son are certainly born of different generations, but underneath her charming wistfulness, and her easy elegance, there’s darkness in so many of Molly’s songs, a darkness that Nick Drake would distill down and explore further in his own work, and in his own way.

This is surely the most unexpected, strangely compelling release in years – a home recording of self-composed songs made in the 1950s and 60s by Molly Drake, the wife of a successful Warwickshire businessman and mother of Nick Drake, the struggling singer-songwriter who acquired legendary status after dying of an overdose of antidepressants in 1974, aged 26. Nick Drake found posthumous fame thanks to his fragile, haunting songs, and his mother was clearly an influence. As his producer Joe Boyd has written, she was "the missing link in the Nick Drake story – there, in the piano chords, are the roots of Nick's harmonies". Molly's piano-backed songs are brief, some just over a minute in length, and are influenced by the popular music of the day, from show tunes to sentimental ballads. But they are remarkable for their blend of confidence, sadness and quiet intimacy. - Robin Denselow

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar