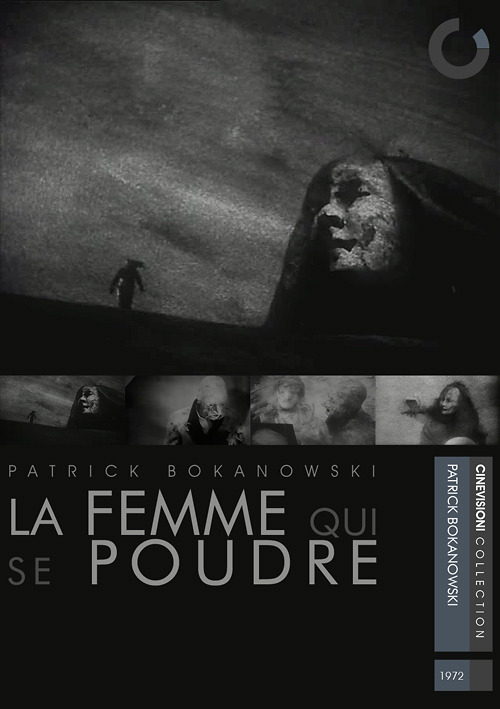

Žena koja se šminka otvara Pandorinu kutiju tjeskoba vezanih za fizičku ljepotu, mladost i poželjnost. Fantazmagorični gotski ekspresionizam, hibrid Švankmajera i Cocteaua.

Something of a hybrid between Jean Cocteau and Jan Svankmajer in its gothic expressionism and artful grotesquerie crossed with the metric precision of Kurt Kren's more clinical materialaktion films that experiment with the plasticity of surfaces (most notably, in the deformed figures that recall the disfiguration and self-mutilation of Kren's short film, 10/65: Selbstverstümmelung), Bokanowski's earliest film, La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is, as the title implies, an evocation of concealment and unmasking, where the mundane act of a Victorian-era woman's ritualistic application of cosmetic powder seemingly opens the window - or perhaps, Pandora's Box - into underlying human anxieties of physical beauty, youth, desirability, and objectification. Reflecting the superficiality of societal notions of beauty through the alienness of landscape and the ephemeral riddle of true identity through epic, soul-searching journeys and faceless phantoms that emerge from thin air before vanishing from view, the terrifying images break apart and eventually disintegrate into irresolvable fragments of haunted memory within the course of the increasingly abstract film, as the waking dream descends ever further into the realm of nightmare and the deepest recesses of the subconscious, unraveling the veil of human vanity to reveal amorphous shadows cast by empty souls. - zazzetounmind.blogspot.com

Art Fags beware! You’re in for a surrealistic scare! La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is a short film that has been no doubt neglected just as the maker of the film Patrick Bokanowski. Despite his Polack sounding name, Patrick Bokanowski is a French filmmaker obviously following in the footsteps of France’s greatest filmmaker/poet Jean Cocteau. Like Cocteau, Bokanowski is able to say something through visuals that the human mind could otherwise never articulate. Like all good poetry, The Woman Who Powders Herself is best looked at without trying to intellectualize and overanalyze. With a short film like this, one should just let the beauty seep into ones soul.

As a child I used to go to a certain unnamed life-saving museum on the east coast. At the museum there is an attraction know as laughing Sal, the former automaton Queen of a boardwalk Funhouse. Unlike most children, I was not afraid of Sal. I actually hoped her grotesque large manmade body would come to life and scare other vulnerable children. But alas, that never happened, but I also never forgot about laughing Sal. As soon as the screen faded to the first image of The Woman Who Powders Herself, I felt as if I was reunited with Sal, in all her beyond homely glory. Like my recollection of laughing Sal, the short film has the feeling of a vague yet soul piercing dream.

The score featured in The Woman Who Powders Herself sounds like it was created by a schizophrenic folly artist. The score (if you can even call it that) compliments the film in a way that very few other films have been successful with. To put it very simply, The Woman Who Powers Herself has neither linear story nor linear sound but a collection of perfectly collected broken pieces that could have been found in Jean Cocteau’s own personal hell (although I believe Cocteau’s hell would feature a man powdering his face). A truly complete piece of cinematic art should always (well almost always) have it’s own original score. Although I consider myself a fan of Luis Buñuel’s Un chien andalou and Aryan genius composer Richard Wagner, the short would have been more of masterpiece had the whole film been of 100% original material.

It is fairly hard to tell whether or not The Woman Who Powders Herself had an influence on any other artists, but for a work of it’s originality and artistry, it had to influence someone. Before he was a hack, it seems that Begotten director E. Elias Merhige took a note or two from The Woman Who Powders Herself. People wearing featureless masks is always a good way to creep out filmgoers, especially in gritty black/white films. Lets not forget the particular dark liquid featured on the floor in The Woman Who Powders Herself that looked like a similar liquid (and with a similar shot composition) as god kills himself inBegotten. The difference between both films is that The Woman Who Powders Herself was at the right runtime at around 15 minutes whereas Begotten was an hour too long. I also wonder in Douglas P. alpha-neo-folk group Death In June saw The Woman Who Powder Herself and decided to wear a featureless mask with his German camouflage outfit.

Some people have said The Woman Who Powders Herself is a commentary on the idea of female beauty in the Victorian era. Although I do not deny this assertion, I could really care less. For me, The Woman Who Powders Herself is a somewhat modern day phantasmagoria that I can enjoy in the comfort of my living room. Very few films transfer me to a dream world of such extravagance and of such a fantastic nature. The Woman Who Powders Herself will stay in my mind’s eye just the way that Eraserhead, The Blood of a Poet, Begotten (the first 15 minutes of course), Fireworks, and Meshes of the Afternoon have been burnt there. - Soiled Sinema

The DVD collection of films by Piotr Kamler turned up last week so I’ve been alternating viewing of that with shorts by Patrick Bokanowski. The latter is less an animator than a filmmaker who uses animation or film effects to achieve his aims, together with masks and very stylised performances. Bokanowski’s early film La femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself, 1972) runs for 15 minutes, and is as remarkable in its own way as his feature-length L’Ange (1982). La femme qui se poudre has the same masked figures engaged in activities which often lack easy interpretation; in both films the atmosphere can shift from absurdity to the edge of horror and back again. For me what’s most remarkable about this particular short is the way it anticipates bothEraserhead and the early films of the Brothers Quay yet still seems little known. The Quays are on record as admiring L’Ange but I’ve yet to see any sign that David Lynch knew of this film in the 1970s. I’d be wary of assuming that Lynch was imitating Bokanowski, artists are quite capable of finding themselves working in similar areas independently.

Films of this nature always benefit from well-matched soundtracks: Piotr Kamler uses recordings by different electronic composers; Eraserhead had Fats Waller and the rumblings and hissings of Alan Splet; the Quays have unique compositions by Lech Jankowski. La femme qui se poudre andL’Ange have outstanding soundtracks by Michèle Bokanowski, the director’s wife and an accomplished avant-garde composer. Her work is as deserving of further attention as that of her husband. DVDs of L’Ange and a collection of Patrick Bokanowski’s short films may be purchased here. - www.johncoulthart.com/

“A prolonged, dense and visually visceral experience of the kind that is rare in cinema today. Difficult to define and locate, its strangeness is quite unique. That its elements are not constructed in a traditional way should not be a barrier to those who wish to cross the bridge to what Jean-Luc Godard proposed as the real story of the cinema—real in the sense of being made of images and sounds rather than texts and illustrations.”—Keith Griffiths

It was only two months ago that I enthused about Patrick Bokanowski’s extraordinary 1982 film, L’Ange, after a TV screening was posted atUbuweb, and ended by wondering whether a DVD copy was available anywhere. Last week Jayne Pilling left a comment on that post alerting me to the film’s availability via the BAA site; I immediately ordered a copy which arrived the next day. So yes, Bokanowski’s film is now available in both PAL and NTSC formats, and the disc includes a short about the making of L’Ange as well as preparatory sketches and an interview with composer Michèle Bokanowski whose score goes a long way to giving the film its unique atmosphere. I mentioned earlier how reminiscent Bokanowski’s film was of later works by the Brothers Quay so it’s no surprise seeing an approving quote from the pair on the DVD packaging:

“Magisterial images seething in the amber of transcendent soundscapes. Drink in these films through eyes and ears.”

If that wasn’t enough, there’s another DVD of the director’s short films available. Anyone who likes David Lynch’s The Grandmother or Eraserhead, or the Quays’ Street of Crocodiles, really needs to see L’Ange. - www.johncoulthart.com/

“Magisterial images seething in the amber of transcendent soundscapes. Drink in these films through eyes and ears.”

If that wasn’t enough, there’s another DVD of the director’s short films available. Anyone who likes David Lynch’s The Grandmother or Eraserhead, or the Quays’ Street of Crocodiles, really needs to see L’Ange. - www.johncoulthart.com/

The good people at Ubuweb have excelled themselves by turning up this 70-minute avant garde work by a director who’d managed to stay resolutely off my radar despite years spent delving for cinematic weirdness. L’Ange (1982) is a film which stands comparison with the more abstracted moments of David Lynch and the Brothers Quay. In fact some scenes (and the music) are so reminiscent of parts of the Quay canon I’d suspect an influence if I didn’t consider that an unfair diminishing of the Brothers’ own considerable talents. So what is L’Ange? Trying to describe this film isn’t exactly easy so it’s simpler to hijack Ubuweb’s own précis:During the seventy minutes of The Angel, viewers see a series of distinct sequences arranged upward along a staircase that seems more mythic than literal. Each of the sequences has its own mood and type of action. Early in the film, a fencer thrusts, over and over, at a doll hanging from the ceiling of a bare room. At first, he is seen in the room at the end of a narrow hallway off the staircase, and later from within the room. He fences, sits in a chair, fences – his movements filmed with a technique that lies somewhere between live action and still photographs. At times, Bokanowski’s imagery is reminiscent of Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographs. Further up the stairs, we find ourselves in a room where a maid brings a jug of milk to a man without hands, over and over. Still later, we are in a room where there seems to be a movie projector pointing at us. Then, in a sequence reminiscent of Méliès and early Chaplin, a man frolics in a bathtub, and in a subsequent sequence gets up, dresses in reverse motion, and leaves for work. The film’s most elaborate sequence takes place in a library in which nine identical librarians work busily in choreographed, slightly fast motion. When the librarians leave work, they are seen in extreme long shot, running in what appears to be a two-dimensional space, ultimately toward a naked woman trapped in a box, which they enter with a battering ram. Then, back in the room with the projector, we are presented with an artist and model in a composition that, at first, declares itself two-dimensional until the artist and model move, revealing that this “obviously” flat space is fact three-dimensional. Finally, a visually stunning passage of projected light reflecting off a series of mirrors introduces The Angel‘s final sequence, of beings on a huge staircase filmed from below; the beings seem to be ascending toward some higher realm. Bokanowski’s consistently distinctive visuals are accompanied by a soundtrack composed by Michèle Bokanowski, Patrick Bokanowski’s wife and collaborator. Like Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari(1919), Bokanowski’s The Angel creates a world that is visually quite distinct from what we consider “reality,” while providing a wide range of implicit references to it and to the history of representing those levels of reality that lie beneath and beyond the conventional surfaces of things.

Asking what it all means is pointless, we’re in the world of dreams here and once again we see how film is able to capture the ambience of dream states in a way no other artform can manage. For an obviously low-budget production there’s real craft and control at work throughout L’Ange, not least in the excellent score—a blend of strings and electronics—which could easily stand alone. Many experimental films of this type quickly outstay their welcome via prolonged repetition or a failure to exploit the imaginative potential of their techniques. Like Lynch and the Quays, Bokanowski successfully balances on the dividing line between narrative and abstraction, finding images unlike any we’ve seen elsewhere. Yes, I enjoyed this a lot, and now I want to watch it again on DVD (if such a thing exists). Fans of The Grandmother and Rehearsals for Extinct Anatomiesare advised to set aside seventy minutes of their time.

Patrick Bokanowski was born in 1943. From 1962 to 1966, he follows studies of photography, optics, of chemistry, under the direction of Henri Dimier, painter and scholar, specialist in the optical phenomena and the perspective systems. The animated films of Jean Mutschler are his first true window on the cinema, and a long time, animation will remain for him a kind of predilection at the same time as a privileged ground of experimentation. The images which it films, Patrick Bokanowski would like to make them more expressive, the more fluid forms: he then puts himself to collect ends of glass, curve, bullé, hammered and tries himself to film with through. The result not being completely convincing, it manufactures optics helped specialists and is interested in reflective surfaces then with the mirrors and the mercury baths, kinds of mirrors moving. Its technique of the reflective mirrors through which it films a completely distorted reality takes all its direction in "At the edge of the lake". This film required for its realization, an erudite provision of almost fifteen mirrors méticuleusement manufactured and selected among tens of samples of work.

In thirty years, Patrick Bokanowski will carry out seven films, without words, where the music composed by his Michele wife, occupies a dominating place. He also exposes paintings, drawings and photographs.

Filmographie

- 1984 : La Part du hasard, 16 mm, couleurs, 56 min

- 1992 : La Plage, 16 mm, couleurs, 14 min

- 1993 : Au bord du lac, 16 mm, couleurs, 6 min

- 2002 : Eclats d'Orphée, 16mm, couleurs, 4 min 35

- 2003 :Le Rêve éveillé, vidéo, couleurs, 41 min

- 2008 : Battements solaires, 35 mm, couleurs, 18 min 40

L'Ange, 1982

Reflecting the seemingly hermetic nature of the individual vignettes through the characters' isolation (reinforced by the dimmed, directional lighting that suffuses the film), Bokanowski, nevertheless, integrally links each episode to the other through modulated visual semblances and recurring images of graduated steps and staircases that bind the assorted leitmotifs together towards an implied vertical movement. At the core of the film's arrangement is a Dante Alighieri-esque (upended) evolution from darkness to light, a conceptual progression that Bokanowski describes as a physical transition through interrelated spaces during his interview with Scott MacDonald for Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers:

"About the overall structure of The Angel, I can say that it is very traditional. You have a staircase, you go from the cellar to the attic. Scenes start falling into place during the dark, shapeless, not very precise starting phase; and then the more the film progresses, the more precise things become, and at the end, it reveals extremely luminous areas. In one of the earliest stages, when I was doing the scenario, I thought that when one comes to the far top of this gigantic house, to an attic room, a last character would appear, some kind of a giant with barely discernible wings, some kind of angelic figure. He would lift the arm of the phonograph, the music would stop, and one would see all the film's scenes in still frames. Very quickly, I disliked the character. He was impossible to film! So, I did not keep this sequence, but that character did give the film its title."

It is interesting to note that despite Bokanowski's strategy to reject the inclusion of a unifying, iconic, titular image, the idea of an underlying celestial entity continues to pervade the film's visual composition through the application of point source lighting, the aforementioned luminosity, that, through light's integral optical properties of diffusion and diffraction, results in the formation of recursive, concentric rays that project a sunburst or halo effect throughout the film - at times, exaggerated and grotesque (as in the expressionistic, elongated, web-like abstract forms of the opening sequence), warm and pastoral (as in the image of a Flemish painting-styled milkmaid serving "the man without hands"), and saturated and disorienting (as in the frenetic, decontextualized, rapidly edited montage of the seemingly subterranean activities (or perhaps imprisonment) of La Femme qui coud).

Particularly illustrative of Bokanowski's aesthetic is the malleability and relativity of dimensional space: blocky, rough hewn lines that resemble woodcut prints are unsuspectingly animated by the initiation of transversal motion (in the sequence of a turbaned operator of a sextant-like instrument facing a seated, veiled figure), extreme long shots blur the delineation between live action and animation sequences (in the interstitial sequence of the liberated librarians encountering a woman in a boxed enclosure), and painterly images transformed into virtual tableaux vivants (in the Vermeer-inspired, L'Homme sans mains). Subverting the flatness of images in order to continually challenge the viewer's spatial and cognitive perception, L'Ange not only illustrates the intrinsic hybridity of film as a static and dynamic medium, but also reinforces the ambiguity and inconcreteness implicit in the aesthetic presentation of the very images themselves, where chaos transforms into order, frailty into perfection, and quotidian into grace.

Patrick Bokanowski: Short Films (1972-1994)

My first exposure to French filmmaker Patrick Bokanowski's experimental cinema was with his transfixing, yet vague and impenetrable magnum opus L'Ange, a Dante Alighieri-esque depiction of intranscendence and moribund ritual that would ingrain the (somewhat reductive) idea that his films were abstract visual studies in structuralism, modulation, and repetition. In hindsight, underneath this cursory first impression of Bokanowski's aesthetic is an intrinsic aspect of his filmmaking that is undeniably artful and innovative - particularly within the context of his short films - and that, like Oskar Fischinger's deconstructed, aural waveforms, approach a synesthetic convergence between image and sound. In his optical experiments with light, reflection, and refraction that transform everyday images into fluid and deformable art objects that redefine the medium of film as a traditional canvas, Bokanowski shares a visual affinity with Aleksandr Sokurov's murky and expressionistic in-line optical distortions in films such as Mother and Son and Oriental Elegy that, like the works of aesthetic forefathers such as Pieter Brueghel the Elder and Caspar David Friedrich, evoke the primal, spiritual landscapes that haunt our consciousness and give form to our waking dreams.

La Femme qui se poudre, 1972

Something of a hybrid between Jean Cocteau and Jan Svankmajer in its gothic expressionism and artful grotesquerie crossed with the metric precision of Kurt Kren's more clinical materialaktion films that experiment with the plasticity of surfaces (most notably, in the deformed figures that recall the disfiguration and self-mutilation of Kren's short film, 10/65 Selbstverstümmelung), Bokanowski's earliest film, La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is, as the title implies, an evocation of concealment and unmasking, where the mundane act of a Victorian-era woman's ritualistic application of cosmetic powder seemingly opens the window - or perhaps, Pandora's Box - into underlying human anxieties of physical beauty, youth, desirability, and objectification. Reflecting the superficiality of societal notions of beauty through the alienness of landscape and the ephemeral riddle of true identity through epic, soul-searching journeys and faceless phantoms that emerge from thin air before vanishing from view, the terrifying images break apart and eventually disintegrate into irresolvable fragments of haunted memory within the course of the increasingly abstract film, as the waking dream descends ever further into the realm of nightmare and the deepest recesses of the subconscious, unraveling the veil of human vanity to reveal amorphous shadows cast by empty souls.

Something of a hybrid between Jean Cocteau and Jan Svankmajer in its gothic expressionism and artful grotesquerie crossed with the metric precision of Kurt Kren's more clinical materialaktion films that experiment with the plasticity of surfaces (most notably, in the deformed figures that recall the disfiguration and self-mutilation of Kren's short film, 10/65 Selbstverstümmelung), Bokanowski's earliest film, La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is, as the title implies, an evocation of concealment and unmasking, where the mundane act of a Victorian-era woman's ritualistic application of cosmetic powder seemingly opens the window - or perhaps, Pandora's Box - into underlying human anxieties of physical beauty, youth, desirability, and objectification. Reflecting the superficiality of societal notions of beauty through the alienness of landscape and the ephemeral riddle of true identity through epic, soul-searching journeys and faceless phantoms that emerge from thin air before vanishing from view, the terrifying images break apart and eventually disintegrate into irresolvable fragments of haunted memory within the course of the increasingly abstract film, as the waking dream descends ever further into the realm of nightmare and the deepest recesses of the subconscious, unraveling the veil of human vanity to reveal amorphous shadows cast by empty souls.

Déjeuner du matin, 1974

Incorporating painterly, Friedrich-like rural landscapes (that prefigure the profoundly isolated, psychological landscape of Sokurov's Mother and Son) set against expressionistic images of elongated shadows, skeletal structures, and highly acute camera angles that distort perspective fields of view, Déjeuner du matin subverts conventional notions of family and domestic ritual to create a haunted portrait of isolation and Sisyphean ritual. Bokanowski sets the tedium of mundane, near-autonomic morning routines on a provincial farmhouse (a looped sequence depicting an inventor drafting his latest design at the break of dawn reinforces this sense of somnambulism) - eating breakfast, shaving, carrying bales of hay - against a sense of claustrophobic inescapability where momentary eruptions of unprovoked domestic violence are attenuated within the oscillations of a lifeline, and even the act of flight through the hills in order to watch the sun rise is made ominous by the churning of the clouds, the fragile balance of near-collapsing structures, and the silence of inorganic, forbidding mountains. Concluding with petrified images of despair and inanimate, seemingly truncated attempt at connection (or perhaps, reconciliation), the tonally jarring incorporation of a melodic, carnivalesque arcade music serves as a wry reinforcement of the theme of eternal cycles of ritual.

Incorporating painterly, Friedrich-like rural landscapes (that prefigure the profoundly isolated, psychological landscape of Sokurov's Mother and Son) set against expressionistic images of elongated shadows, skeletal structures, and highly acute camera angles that distort perspective fields of view, Déjeuner du matin subverts conventional notions of family and domestic ritual to create a haunted portrait of isolation and Sisyphean ritual. Bokanowski sets the tedium of mundane, near-autonomic morning routines on a provincial farmhouse (a looped sequence depicting an inventor drafting his latest design at the break of dawn reinforces this sense of somnambulism) - eating breakfast, shaving, carrying bales of hay - against a sense of claustrophobic inescapability where momentary eruptions of unprovoked domestic violence are attenuated within the oscillations of a lifeline, and even the act of flight through the hills in order to watch the sun rise is made ominous by the churning of the clouds, the fragile balance of near-collapsing structures, and the silence of inorganic, forbidding mountains. Concluding with petrified images of despair and inanimate, seemingly truncated attempt at connection (or perhaps, reconciliation), the tonally jarring incorporation of a melodic, carnivalesque arcade music serves as a wry reinforcement of the theme of eternal cycles of ritual.

La Plage, 1992

Composed of four chapters depicting optical modulations of scenes from a day at the beach, La Plage illustrates Bokanowski's continued fascination (and experimentation) with the chromic, refractive, and reflective properties of glass to create films that redefine the materiality of celluloid and explore the plasticity of surfaces to transform everyday objects into works of art. The high contrast, blue tinting of the first chapter prefigures the opening sequence of Dolce in its evocation of nocturnal tempest (and perhaps even a glimpse of the forking of waters in Sharunas Bartas' Few of Us). The second chapter forgoes the darker chromic filters while retaining the film's high contrast to create a sense of floating otherworldliness to the images, an atmosphere that is further emphasized through a shift in camera framing from people anchored on the foreground (generally near the bottom) of the frame in the previous chapter, to people framed in the middle of the shot, seemingly suspended in the enveloping water between the terrestrial and the celestial. The third chapter introduces variable density optics (where the multiple indices of refraction reside at various sectors within the same lens) into the camera's line of sight that refract light into visually unexpected transmittive or reflective angles such that organic shapes become angular and compartmentalized into cubist-like organic geometries, and monolithic forms take on an appearance of fluidity and motion. Creating nodal point images that present a differential mapping of "concentrations of matter", Bokanowski cleverly redefines notions of visibility into relativistic realms of motion and inertia. Lastly, the fourth chapter returns to the chromic filters of earliest chapters. Concluding with a frozen image of a woman and child gazing out to sea that is framed against the warm, red and amber hues of a seeming sunset, the parting shot becomes a reinforcing image of return to innocence and the beauty of simplicity.

Composed of four chapters depicting optical modulations of scenes from a day at the beach, La Plage illustrates Bokanowski's continued fascination (and experimentation) with the chromic, refractive, and reflective properties of glass to create films that redefine the materiality of celluloid and explore the plasticity of surfaces to transform everyday objects into works of art. The high contrast, blue tinting of the first chapter prefigures the opening sequence of Dolce in its evocation of nocturnal tempest (and perhaps even a glimpse of the forking of waters in Sharunas Bartas' Few of Us). The second chapter forgoes the darker chromic filters while retaining the film's high contrast to create a sense of floating otherworldliness to the images, an atmosphere that is further emphasized through a shift in camera framing from people anchored on the foreground (generally near the bottom) of the frame in the previous chapter, to people framed in the middle of the shot, seemingly suspended in the enveloping water between the terrestrial and the celestial. The third chapter introduces variable density optics (where the multiple indices of refraction reside at various sectors within the same lens) into the camera's line of sight that refract light into visually unexpected transmittive or reflective angles such that organic shapes become angular and compartmentalized into cubist-like organic geometries, and monolithic forms take on an appearance of fluidity and motion. Creating nodal point images that present a differential mapping of "concentrations of matter", Bokanowski cleverly redefines notions of visibility into relativistic realms of motion and inertia. Lastly, the fourth chapter returns to the chromic filters of earliest chapters. Concluding with a frozen image of a woman and child gazing out to sea that is framed against the warm, red and amber hues of a seeming sunset, the parting shot becomes a reinforcing image of return to innocence and the beauty of simplicity.

Au bord du lac, 1994

Bokanowski returns to the complex - and mind-bending - optical array of pinholes, mirrors, prisms, and refractive substrates of his earlier film, La Plage to create the whimsical and playful Au bord du lac. The film is composed of mundane, everyday scenes of recreation and leisure on an idyllic, sunny day at a park that overlooks a lake - rowing a boat, playing a game of volleyball, rollerskating, bicycling, reading a newspaper, sunbathing, riding on horseback, or strolling on the promenade - shot through optical distortions to create fractured and knotted images that resemble embellished, gothic fairytale illustrations or appear to resolve into morphing, geometric patterns of fluid motion. Evoking the vibrant colors and sun-soaked palette of an invigorated Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Bokanowski transforms the quotidian into an infinitely mesmerizing dynamic kaleidoscope of shape-shifting textures and self-reconstituting objects of organic, abstract art.

Bokanowski returns to the complex - and mind-bending - optical array of pinholes, mirrors, prisms, and refractive substrates of his earlier film, La Plage to create the whimsical and playful Au bord du lac. The film is composed of mundane, everyday scenes of recreation and leisure on an idyllic, sunny day at a park that overlooks a lake - rowing a boat, playing a game of volleyball, rollerskating, bicycling, reading a newspaper, sunbathing, riding on horseback, or strolling on the promenade - shot through optical distortions to create fractured and knotted images that resemble embellished, gothic fairytale illustrations or appear to resolve into morphing, geometric patterns of fluid motion. Evoking the vibrant colors and sun-soaked palette of an invigorated Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Bokanowski transforms the quotidian into an infinitely mesmerizing dynamic kaleidoscope of shape-shifting textures and self-reconstituting objects of organic, abstract art.

La Femme qui se poudre, 1972

Something of a hybrid between Jean Cocteau and Jan Svankmajer in its gothic expressionism and artful grotesquerie crossed with the metric precision of Kurt Kren's more clinical materialaktion films that experiment with the plasticity of surfaces (most notably, in the deformed figures that recall the disfiguration and self-mutilation of Kren's short film, 10/65 Selbstverstümmelung), Bokanowski's earliest film, La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is, as the title implies, an evocation of concealment and unmasking, where the mundane act of a Victorian-era woman's ritualistic application of cosmetic powder seemingly opens the window - or perhaps, Pandora's Box - into underlying human anxieties of physical beauty, youth, desirability, and objectification. Reflecting the superficiality of societal notions of beauty through the alienness of landscape and the ephemeral riddle of true identity through epic, soul-searching journeys and faceless phantoms that emerge from thin air before vanishing from view, the terrifying images break apart and eventually disintegrate into irresolvable fragments of haunted memory within the course of the increasingly abstract film, as the waking dream descends ever further into the realm of nightmare and the deepest recesses of the subconscious, unraveling the veil of human vanity to reveal amorphous shadows cast by empty souls.

Something of a hybrid between Jean Cocteau and Jan Svankmajer in its gothic expressionism and artful grotesquerie crossed with the metric precision of Kurt Kren's more clinical materialaktion films that experiment with the plasticity of surfaces (most notably, in the deformed figures that recall the disfiguration and self-mutilation of Kren's short film, 10/65 Selbstverstümmelung), Bokanowski's earliest film, La Femme qui se poudre (The Woman Who Powders Herself) is, as the title implies, an evocation of concealment and unmasking, where the mundane act of a Victorian-era woman's ritualistic application of cosmetic powder seemingly opens the window - or perhaps, Pandora's Box - into underlying human anxieties of physical beauty, youth, desirability, and objectification. Reflecting the superficiality of societal notions of beauty through the alienness of landscape and the ephemeral riddle of true identity through epic, soul-searching journeys and faceless phantoms that emerge from thin air before vanishing from view, the terrifying images break apart and eventually disintegrate into irresolvable fragments of haunted memory within the course of the increasingly abstract film, as the waking dream descends ever further into the realm of nightmare and the deepest recesses of the subconscious, unraveling the veil of human vanity to reveal amorphous shadows cast by empty souls.Déjeuner du matin, 1974

Incorporating painterly, Friedrich-like rural landscapes (that prefigure the profoundly isolated, psychological landscape of Sokurov's Mother and Son) set against expressionistic images of elongated shadows, skeletal structures, and highly acute camera angles that distort perspective fields of view, Déjeuner du matin subverts conventional notions of family and domestic ritual to create a haunted portrait of isolation and Sisyphean ritual. Bokanowski sets the tedium of mundane, near-autonomic morning routines on a provincial farmhouse (a looped sequence depicting an inventor drafting his latest design at the break of dawn reinforces this sense of somnambulism) - eating breakfast, shaving, carrying bales of hay - against a sense of claustrophobic inescapability where momentary eruptions of unprovoked domestic violence are attenuated within the oscillations of a lifeline, and even the act of flight through the hills in order to watch the sun rise is made ominous by the churning of the clouds, the fragile balance of near-collapsing structures, and the silence of inorganic, forbidding mountains. Concluding with petrified images of despair and inanimate, seemingly truncated attempt at connection (or perhaps, reconciliation), the tonally jarring incorporation of a melodic, carnivalesque arcade music serves as a wry reinforcement of the theme of eternal cycles of ritual.

Incorporating painterly, Friedrich-like rural landscapes (that prefigure the profoundly isolated, psychological landscape of Sokurov's Mother and Son) set against expressionistic images of elongated shadows, skeletal structures, and highly acute camera angles that distort perspective fields of view, Déjeuner du matin subverts conventional notions of family and domestic ritual to create a haunted portrait of isolation and Sisyphean ritual. Bokanowski sets the tedium of mundane, near-autonomic morning routines on a provincial farmhouse (a looped sequence depicting an inventor drafting his latest design at the break of dawn reinforces this sense of somnambulism) - eating breakfast, shaving, carrying bales of hay - against a sense of claustrophobic inescapability where momentary eruptions of unprovoked domestic violence are attenuated within the oscillations of a lifeline, and even the act of flight through the hills in order to watch the sun rise is made ominous by the churning of the clouds, the fragile balance of near-collapsing structures, and the silence of inorganic, forbidding mountains. Concluding with petrified images of despair and inanimate, seemingly truncated attempt at connection (or perhaps, reconciliation), the tonally jarring incorporation of a melodic, carnivalesque arcade music serves as a wry reinforcement of the theme of eternal cycles of ritual. La Plage, 1992

Composed of four chapters depicting optical modulations of scenes from a day at the beach, La Plage illustrates Bokanowski's continued fascination (and experimentation) with the chromic, refractive, and reflective properties of glass to create films that redefine the materiality of celluloid and explore the plasticity of surfaces to transform everyday objects into works of art. The high contrast, blue tinting of the first chapter prefigures the opening sequence of Dolce in its evocation of nocturnal tempest (and perhaps even a glimpse of the forking of waters in Sharunas Bartas' Few of Us). The second chapter forgoes the darker chromic filters while retaining the film's high contrast to create a sense of floating otherworldliness to the images, an atmosphere that is further emphasized through a shift in camera framing from people anchored on the foreground (generally near the bottom) of the frame in the previous chapter, to people framed in the middle of the shot, seemingly suspended in the enveloping water between the terrestrial and the celestial. The third chapter introduces variable density optics (where the multiple indices of refraction reside at various sectors within the same lens) into the camera's line of sight that refract light into visually unexpected transmittive or reflective angles such that organic shapes become angular and compartmentalized into cubist-like organic geometries, and monolithic forms take on an appearance of fluidity and motion. Creating nodal point images that present a differential mapping of "concentrations of matter", Bokanowski cleverly redefines notions of visibility into relativistic realms of motion and inertia. Lastly, the fourth chapter returns to the chromic filters of earliest chapters. Concluding with a frozen image of a woman and child gazing out to sea that is framed against the warm, red and amber hues of a seeming sunset, the parting shot becomes a reinforcing image of return to innocence and the beauty of simplicity.

Composed of four chapters depicting optical modulations of scenes from a day at the beach, La Plage illustrates Bokanowski's continued fascination (and experimentation) with the chromic, refractive, and reflective properties of glass to create films that redefine the materiality of celluloid and explore the plasticity of surfaces to transform everyday objects into works of art. The high contrast, blue tinting of the first chapter prefigures the opening sequence of Dolce in its evocation of nocturnal tempest (and perhaps even a glimpse of the forking of waters in Sharunas Bartas' Few of Us). The second chapter forgoes the darker chromic filters while retaining the film's high contrast to create a sense of floating otherworldliness to the images, an atmosphere that is further emphasized through a shift in camera framing from people anchored on the foreground (generally near the bottom) of the frame in the previous chapter, to people framed in the middle of the shot, seemingly suspended in the enveloping water between the terrestrial and the celestial. The third chapter introduces variable density optics (where the multiple indices of refraction reside at various sectors within the same lens) into the camera's line of sight that refract light into visually unexpected transmittive or reflective angles such that organic shapes become angular and compartmentalized into cubist-like organic geometries, and monolithic forms take on an appearance of fluidity and motion. Creating nodal point images that present a differential mapping of "concentrations of matter", Bokanowski cleverly redefines notions of visibility into relativistic realms of motion and inertia. Lastly, the fourth chapter returns to the chromic filters of earliest chapters. Concluding with a frozen image of a woman and child gazing out to sea that is framed against the warm, red and amber hues of a seeming sunset, the parting shot becomes a reinforcing image of return to innocence and the beauty of simplicity.Au bord du lac, 1994

Bokanowski returns to the complex - and mind-bending - optical array of pinholes, mirrors, prisms, and refractive substrates of his earlier film, La Plage to create the whimsical and playful Au bord du lac. The film is composed of mundane, everyday scenes of recreation and leisure on an idyllic, sunny day at a park that overlooks a lake - rowing a boat, playing a game of volleyball, rollerskating, bicycling, reading a newspaper, sunbathing, riding on horseback, or strolling on the promenade - shot through optical distortions to create fractured and knotted images that resemble embellished, gothic fairytale illustrations or appear to resolve into morphing, geometric patterns of fluid motion. Evoking the vibrant colors and sun-soaked palette of an invigorated Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Bokanowski transforms the quotidian into an infinitely mesmerizing dynamic kaleidoscope of shape-shifting textures and self-reconstituting objects of organic, abstract art.

Bokanowski returns to the complex - and mind-bending - optical array of pinholes, mirrors, prisms, and refractive substrates of his earlier film, La Plage to create the whimsical and playful Au bord du lac. The film is composed of mundane, everyday scenes of recreation and leisure on an idyllic, sunny day at a park that overlooks a lake - rowing a boat, playing a game of volleyball, rollerskating, bicycling, reading a newspaper, sunbathing, riding on horseback, or strolling on the promenade - shot through optical distortions to create fractured and knotted images that resemble embellished, gothic fairytale illustrations or appear to resolve into morphing, geometric patterns of fluid motion. Evoking the vibrant colors and sun-soaked palette of an invigorated Vincent van Gogh in Arles, Bokanowski transforms the quotidian into an infinitely mesmerizing dynamic kaleidoscope of shape-shifting textures and self-reconstituting objects of organic, abstract art.

This video edition brings together the only two documentaries directed to date by Patrick Bokanowski, filmmaker of the imaginary. For 35 years he has brought us a body of work rich in extraordinary characters inhabiting mental environments, on the edge between figurative and abstract art. But here, rather than weaving fantastic dreams, he presents in a direct and realistic style two striking personalities who themselves work to uncover the world of the imaginary and the world of dreams, the painter Henri Dimier, and the psychotherapist Colette Aboulker-Muscat:

La Part Du Hasard

Henri Dimier's hand lets itself be guided by total creative spontaneity, creating a dialogue with the sheet of paper, a conversation with the work in progress, the jubilatory quality of the vibrations of hand on paper. Liberty, fantasy and chance are Henri Dimier's three watchwords.

Le Reve Eveille

Colette Aboulker-Muscat has taught Waking Dream for the past forty years in Jerusalem. To each person who comes for a consultation, she offers a short story leading to a waking dream, equal in intensity to a night dream. The surprise provoked by the story, and the shortness of the treatment are, for her, essential aspects of the process. The mental imagery itself allows one to overcome a problem or an illness.

Film Listing- La Part Du Hasard (The Role Of Chance, 1984, 52 mins)

- Le Reve Eveille (Waking Dream, 2003, 41 mins)

Patrick Bokanowski

Poput

deteta koje je dobilo novu igračku, obradovao sam se nedavnom "otkriću"

- eksperimentalnim filmovima Patricka Bokanowskog. Za razliku od svih

avangardista na koje sam do sada nailazio i čije delo je na ovaj ili

(uglavnom) onaj način bilo moguće donekle "protumačiti", kod Bokanowskog

se postavlja sledeće pitanje: Da li uopšte tragati za značenjem ili se

jednostavno prepustiti enigmatičnom sklopu snenih/košmarnih slika i

"odgovarajućih" zvukova (tj. "muzike" Michèle Bokanowski, supruge i

stalne saradnice), koji kao da pokušava da prodre u podsvest podsvesnog,

i tako ad infinitum? Dok se za ranije radove još i može reći da su

opipljivi i dokučivi, skloni čak i (opreznom!) svrstavanju pod neki

žanr, a istovremeno ograničeni u svetu bez granica, većina kasnijih

sinematskih eksperimenata ostaje van svakog domašaja, iako se u

deformisanim prikazima naslućuje stvarnost (ili umetnikovo poimanje

iste). U svakom sledećem moguće je prepoznati nešto iz prethodnih, s tim

što to neodređeno (ili pak određeno?) "nešto" uvek deluje drugačije, u

beskrajnom ciklusu halucinogenih vizija.

Verujem da bilo kakav pokušaj

detaljn(ij)e analize ovih neobičnih (nad-nadrealnih) ostvarenja izaziva

grčeve i glavobolju filmskih kritičara, filozofa, psihologa i ostalih

koji se usuđuju da ih razlažu, jer filmovi Patricka Bokanowskog prkose

gotovo svakoj definiciji sedme umetnosti i rečima koje bi ih bar

približno opisale. Međutim, uprkos svojoj neuhvatljivosti, nemirnom

plutanju između redova i na marginama snova i pod-snova, oni pružaju

neosporan užitak, koji podrazumeva "open-minded" (čitaj:

"razjapljenoumnog") gledaoca, željnog inspirativnog i nezaboravnog

iskustva. Verovatno će zvučati kontradiktorno ovo što ću reći

(protivurečnost je ovde neizbežna), ali da je ekran bio voda, dok su se

po njemu razlivale poetično-haotične autorove misli i ideje, udavio bih

se, znajući unapred da je u takvoj vodi nemoguće udaviti se.

Uz nekoliko snapshot-ova, škrtih

komentara (u opširnijim bih se sigurno izgubio) i citata, potrudiću se

da predstavim osam kratkometražnih i jedan dugometražni film koji (uz za

sada nedostupni La part du hasard iz 1984) sačivanjaju filmografiju

Bokanowskog.

"Patrick Bokanowski, French filmmaker and artist born in 1943, has developed a manner of treating filmic material that crosses over traditional boundaries of film genre: short film, experimental cinema and animation. His work lies on the edge between optical and plastic art, in a 'gap' of constant reinvention. Patrick Bokanowski challenges the idea that cinema must, essentially, reproduce reality, our everyday thoughts and feelings. His films contradict the photographic 'objectivity' that is firmly tied to the essence of film production the world over. Bokanowski's experiments attempt to open the art of film up to other possibilities of expression, for example by 'warping' his camera lens (he prefers the term 'subjective' to 'objective' - the French word for 'lens'), thus testifying to a purely mental vision, unconcerned with film's conventional representations, affecting and metamorphosing reality, and thereby offering to the viewer of his films new adventures in perception." - Pierre Coulibeuf

La femme qui se podre (The Woman Who Powders Herself, 1972)

Ko bi rekao da se iza jednog

ovako bezazlenog naslova krije neslućena art-horror fantazija? Ispunjena

onostranim senkama i avetima (pri čemu je nemoguće odrediti pravac

"onostranosti"), koje svojim bizarnim "postupcima" izazivaju jezu, ona

nemilosrdno golica maštu i budi bezimenu fobiju. Ne bi me iznenadilo da

su, u određenom trenutku, reditelji poput Davida Lyncha, blizanaca

Timothya i Stephena Quaya ili Guya Maddina imali na umu Ženu koja

stavlja puder...

Dèjeuner du matin (Lunch in the Morning, 1974)"Yet it's very much like a new masterpiece that blazes its own trail without resembling anything else that has been seen before (although you could claim a vague family resemblance with Goya or German expressionism). But whatever one wants to analyze or not analyze in this film, it is a work which disturbs one deeply. The music (by Michèle Bokanowski) is pitched high, as if synthesized from the whistling wind; it's the sound a flying saucer might make along with Tibetan trumpets and overheard bits and pieces of people talking in a language you don't understand. You wonder how everything you are looking at was fabricated. There are a few double exposures, or else 'real people' wearing grotesque Frankenstein-like masks or stockings over their faces. They are either filmed through a dirty glass or else they metamorphose into drawings (a character can be drawn or else volumes come into focus and assemble themselves into a weird and yet coherent form): as a result, the space the film is describing is being constantly scrambled; it's a film without any floor in it and, as a spectator, when you are watching it, even if you are comfortably seated, your own seat leaves the ground. One notices these briefly passing creatures (one of which is, yes, a woman powdering herself) slowly and deliberately undertaking acts you don't quite understand, but which are clearly of a ghastly nature (perhaps a murder?); one watches two 'real' characters suddenly change into ink spots while a bombardment of drawn or painted meteorites explodes on what might be the 'earth'; one looks at somebody pouring coffee into a full cup which then overflows into an endlessly dark and ink-like trail; at which point you say to yourself that what is going on here, in this black and upsetting film, has the logic of a nightmare."

Dominique Noguez, The Logic of Nightmare

Nalik istraživanju koje sprovodi

u svom prvencu, ublažavajući "košmarnost" za koju nijansu, Bokanowski

još jednom nastoji (a u pitanju je puka pretpostavka) da izazove strah

taman kada pomislite da razloga za strah nema. Apstraktne, lebdeće

pejzaže povezuje jedna nit - dugokosi dečak, čije je bežanje od, recimo,

svakodnevnog života, u par navrata prekinuto vriskom od koga se i

sleđena krv ledi. Zajedno sa La femme qui se poudre, Dèjeuner du matin

bi se mogao posmatrati kao predgovor za film Eraserhead, gorepomenutog

reditelja.

"This very short film takes us outside of time as we know it and drops us into a different kind of timespan and into a different world. To a certain extent it can be called 'surreal,' but only in reference to the filmmaker's own vision. It can be called a dreamscape, but don't go looking for any hidden meanings in these disturbing images. Such as that long nocturnal hallway we've walked down in our dreams, down which psychoanalysts have followed their customers, or on their own behalf. It leads us into the deepest depth of ourselves. Plastically speaking, the work is superb. It touches us physically before affecting us metaphysically. In the dark depths of a field, a strange and displaced peasantry is scything an invisible yield." - Claude Mauriac, V.S.D. magazin, Jun 1979.

L'ange (The Angel, 1976-1982)

Počev od mačevaoca koji probada

porcelansku lutku okačenu o plafon, preko starice koja čoveku bez šaka

donosi krčag s mlekom, mladića koji prebire po biserima, kupanja

starijeg muškarca i njegovog psa u limenoj kadi i identičnih

bibliotekara koji užurbano sređuju arhivu (?), a zatim dolaze do nage

žene zarobljene u kocki, pa sve do "uspona" u završnici, praćenog

mističnim probijanjem svetlosti, Anđeo ne prestaje da fascinira svojom

vrtoglavom lepotom, kakva god da je njena svrha. Možda je cilj ove

misteriozne "fantazije" da ovaploti haos iz glave nebeskog bića koje se

sa visina nagledalo svega i svačega, a onda kroz kakav filter propustilo

ono što je zapamtilo i u To sakrilo odgovor za postizanje

savršenstva...

"During the seventy minutes of The Angel, viewers see a series of distinct sequences arranged upward along a staircase that seems more mythic than literal. Each of the sequences has its own mood and type of action. Early in the film, a fencer thrusts, over and over, at a doll hanging from the ceiling of a bare room. At first, he is seen in the room at the end of a narrow hallway off the staircase, and later from within the room. He fences, sits in a chair, fences - his movements filmed with a technique that lies somewhere between live action and still photographs. At times, Bokanowski's imagery is reminiscent of Etienne-Jules Marey's chronophotographs. Further up the stairs, we find ourselves in a room where a maid brings a jug of milk to a man without hands, over and over. Still later, we are in a room where there seems to be a movie projector pointing at us. Then, in a sequence reminiscent of Melies and early Chaplin, a man frolics in a bathtub, and in a subsequent sequence gets up, dresses in reverse motion, and leaves for work. The film's most elaborate sequence takes place in a library in which nine identical librarians work busily in choreographed, slightly fast motion. When the librarians leave work, they are seen in extreme long shot, running in what appears to be a two-dimensional space, ultimately toward a naked woman trapped in a box, which they enter with a battering ram. Then, back in the room with the projector, we are presented with an artist and model in a composition that, at first, declares itself two-dimensional until the artist and model move, revealing that this "obviously" flat space is fact three-dimensional. Finally, a visually stunning passage of projected light reflecting off a series of mirrors introduces The Angel's final sequence, of beings on a huge staircase filmed from below; the beings seem to be ascending toward some higher realm. Bokanowski's consistently distinctive visuals are accompanied by a soundtrack composed by Michèle Bokanowski, Patrick Bokanowski's wife and collaborator. Like Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), Bokanowski's The Angel creates a world that is visually quite distinct from what we consider "reality," while providing a wide range of implicit references to it and to the history of representing those levels of reality that lie beneath and beyond the conventional surfaces of things." - Scott MacDonald, "A Critical Cinema: Interviews With Independent Filmamkers"

La plage (The Beach, 1992)

Prvi filmić u kome Bokanowski u potpunosti menja svoj pristup - mesto jeze zauzima harmonija.

"There are now films like THE BEACH which belong to a sort of aristocracy of experimental film - which is just an arbitrary term meaning that a film's plastic aspect is just as important as its meaning or storyline - and Patrick Bokanowski's film has an almost classical quality in this sense, insofar as it is composed like a painting, or, perhaps because of Michèle Bokanowski's contribution, like a piece of music. In THE BEACH, one no longer associates his work with Kafka or Isidore Ducasse, but rather with the light-filled drawings of Victor Hugo or Seurat, Tanguy or even Mir-. It's as if a period of nightmares had come to an end, and a new sense of something like serenity had taken over." - Dominique Noguez

Au bord du lac (By the Lake, 1994)

Jezerska idila, pod kaleidoskopskim svetlom...

"It is true that the unidentified people being filmed are not there simply for the actions they are performing, but the time that the scene is taking to be completed is also beyond any normal definition. The colors vary, and we are plunged many years back in time, no doubt because the shot is suddenly reminding us of Van Gogh or Gauguin and the color-tones they used. We are not at the side of any identifiable lake, we are swept up in a different sort of space-time context by the light, the movement and the colors that the place evoked in Patrick Bokanowski's mind. The shore we are on is the quintessence of lakehood, and, as happens in his previous film, THE BEACH, it's as if the proximity of water metamorphosed everything around, fluidizing all of the matter into endless spirals before our delighted eyes." - Jacques Kermabon, BREF magazin, Mart, 1994.

Flammes (Flames, 1998)

U ovom filmiću Bokanowski koristi isečke iz svojih prethodnih dela, maskirajući ih primenom digitalnih efekata...

Éclats d'Orphée (Shreds of Orpheus, 2002)

Brzopotezna

ekstremno-eksperimentalna pozorišna predstava... ili ?!#$%&/ - u

svakom slučaju, zanimljivo iskakanje autora iz dotadašnjeg "šablona".

Le canard à l'orange (2002)

Razigrana domaćica priprema jelo

iz naslova. Kada joj se pridruži nezvani gost, antropomorfni krokodil,

počinje jurnjava po kuhinji, koja se završava odletanjem patke u

slobodu. Ukratko, Le canard à l'orange je kao live-action Woody

Woodpecker (aka Pera Detlić), snimljen pod dejstvom sumnjivih

"sredstava"...

Battements solaires (Solar Beats, 2008)

Solar Beats bi bilo lepo videti na velikom platnu. Sukob animirane i igrane forme. Vatromet.

Za kraj, još jedna preporuka: Patrick Bokanowski @ filmref.com, autor: Acquarello.

Michèle Bokanowski - Tabou

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGLClHaS5P4

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar