Izvrsna formula za stranicu posvećenu klasičnoj muzici: kratki interpretacijski/uvodni tekst + YouTube snimka/e neke znamenite skladbe. A izbor je fantastičan.

classical20.com/

György Ligeti – San Francisco Polyphony (1973-74)

Written for a normal symphony orchestra complement with an expanded triple woodwind section (including piccolos, alto flute, oboe d’amore, English horn, E flat clarinet, bass clarinet, and double-bassoon), this work was commissioned by San Francisco Symphony Orchestra.

The piece opens with a dense texture made up of many individual melodic lines. In contrast to the Ligeti‘s early pieces, which used the shimmering moving clusters of what Ligeti calls “micropolyphony,” this composition uses much wider spacing and aims for “drier, sharper, and more graphic … melodic lines” that are more “translucent.” The piece is characterized by the subtle technique of timbre modulation achieved through the constant reorchestration of dynamic material.

At the beginning, certain melodies stand out from a group becuase they are played by several instruments in unison. The number of voices is very gradually reduced, producing an unusual ascending-pitch illusion which leaves only the higher woodwinds playing.

The winds continue to float, cycling in the air until interrupted by a wide-ranging, very quiet dissonant string chord. Out of that sustained mass, melodies again begin to emerge, slowly at first and then in an onrushing cacophony of strings (here the winds hold a sustained tone). The rushing tempo is gradually slowed down to a cycling pattern, which is taken up by the winds as the strings return to a sustained chord. Heroic and passionate melodic gestures arise first in the unison horns and then in the strings, as the other instruments re-create the dense atmospheric bed heard at the beginning.

All the players then begin different fixed cycling patterns. Once again the number of instruments playing is very gradually reduced, this time creating an illusion of depth change. A very mysterious timbre is left with very high strings, very low strings, and a high brittle piano trill. A shockingly loud bass drum shot occurs as the strings continue to hold. The percussion blast initates a high woodwind cluster (reminding one of Ligeti’s early orchestral work, Atmospheres). A second percussive shock comes from a gong which increases the intensity of the massed winds.

Underscored by low string drones, the winds begin trills like the calls of extraterrestial birds. These trills are gradually modified into quickly running patterns for a solo violin, which are spread to the piano and xylophone, then to winds and back to the string section — a wonderful instance of the very subtle shifting of timbres which characterizes much of this work. A slowly unfolding horn melody appears within these patterns, the melody being transferred to various winds and brass. This whirlwind continues unabated (as if all the melodies in the world have become one giant wave pattern), changing its orchestration, ebbing slightly at points, and then after approximately three minutes intensifying toward a loud and sudden conclusion.

Underscored by low string drones, the winds begin trills like the calls of extraterrestial birds. These trills are gradually modified into quickly running patterns for a solo violin, which are spread to the piano and xylophone, then to winds and back to the string section — a wonderful instance of the very subtle shifting of timbres which characterizes much of this work. A slowly unfolding horn melody appears within these patterns, the melody being transferred to various winds and brass. This whirlwind continues unabated (as if all the melodies in the world have become one giant wave pattern), changing its orchestration, ebbing slightly at points, and then after approximately three minutes intensifying toward a loud and sudden conclusion.

Berliner Philharmoniker conducted by Jonathan Nott.

Igor Stravinsky – Three Japanese Lyrics (1913)

Stravinsky’s Three Japanese Lyrics (1912-1913) were composed just as the taste for all things Oriental, from fine arts to fashion, was reaching its apex throughout Europe. Nowhere was this fad more rampant than in Paris, where the composer lived and, in 1912, had come upon an anthology of Japanese poetry translated into Russian, providing him with the texts for a group of three songs. These terse and somewhat mournful songs — “Akahito,” “Mazatsumi,” and “Tsaraiuki” — represent the composer’s most overt adoption of Far Eastern subject matter. Like many of Stravinsky’s works which draw upon elements from “exotic” sources, the songs reveal a degree of detachment, objectivity and stylization.

The Three Japanese Lyrics were composed some 15 to 18 months after Le sacre du printemps (1911-1913) was completed; as in that seminal ballet, the songs’ melodic material is based upon the repetition of numerous small cells. “Akahito” features a six-note ostinato comprised of slow, ornamented eighth notes that run throughout the song, while “Tsamaiuki” contains tiny refrain figures that are likewise repeated in an ostinato pattern. The Lyrics suggest a similarity to Le sacre du printemps in terms of subject matter as well. Both illustrate the dawning of spring, but while Le sacre du printemps expresses the death of winter through violence and elemental force, the Lyrics draw attention elsewhere. Here the emphasis is more upon the visual, decorative aspects of the season, symbolized by the color white — patterns of white flowers set against fresh snowfall.

Texturally, the Lyrics reveal another significant influence: Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (1912). Stravinsky attended a performance of the revolutionary melodrama in Berlin in December 1912, and Schoenberg’s band of flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano was a likely inspiration for the instrumentation of the Lyrics (two flutes, two clarinets, and piano quintet). Moreover, the Lyrics, despite their clearly tonal language, employ harsh sonorities and free chromaticism to a greater extent than in Stravinsky’s previous works.

Following their first performance in 1914, many listeners were taken by the Lyrics’ metrical freedom and ambiguity. Indeed, rather than relying upon stereotyped orientalist clichés like pentatonic scales and garish ornamentation, Stravinsky emulates Japanese speech patterns with a remarkable degree of authenticity.

The Three Japanese Lyrics were composed some 15 to 18 months after Le sacre du printemps (1911-1913) was completed; as in that seminal ballet, the songs’ melodic material is based upon the repetition of numerous small cells. “Akahito” features a six-note ostinato comprised of slow, ornamented eighth notes that run throughout the song, while “Tsamaiuki” contains tiny refrain figures that are likewise repeated in an ostinato pattern. The Lyrics suggest a similarity to Le sacre du printemps in terms of subject matter as well. Both illustrate the dawning of spring, but while Le sacre du printemps expresses the death of winter through violence and elemental force, the Lyrics draw attention elsewhere. Here the emphasis is more upon the visual, decorative aspects of the season, symbolized by the color white — patterns of white flowers set against fresh snowfall.

Texturally, the Lyrics reveal another significant influence: Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (1912). Stravinsky attended a performance of the revolutionary melodrama in Berlin in December 1912, and Schoenberg’s band of flute, clarinet, violin, cello, and piano was a likely inspiration for the instrumentation of the Lyrics (two flutes, two clarinets, and piano quintet). Moreover, the Lyrics, despite their clearly tonal language, employ harsh sonorities and free chromaticism to a greater extent than in Stravinsky’s previous works.

Following their first performance in 1914, many listeners were taken by the Lyrics’ metrical freedom and ambiguity. Indeed, rather than relying upon stereotyped orientalist clichés like pentatonic scales and garish ornamentation, Stravinsky emulates Japanese speech patterns with a remarkable degree of authenticity.

I. Akahito

II. Mazatsumi

III. Tsaraiuki

II. Mazatsumi

III. Tsaraiuki

Evelyn Lear, soprano; Columbia Symphony, cond. Robert Craft. Art by Tensho Shubun.

Download sheet music as PDF:

Stravinsky_-_3_Japanese_Lyrics_VoicePiano

Stravinsky_-_3_Japanese_Lyrics_VoicePiano

Giya Kancheli – Morning Prayers (1990)

Giya Kancheli (Georgian: born 10 August 1935 in Tbilisi) is a Georgian composer resident in Belgium.Since 1991, Kancheli has lived in Western Europe: first in Berlin, and since 1995 in Antwerp, where he is composer-in-residence for the Royal Flemish Philharmonic. [source]

Morning Prayers,

for chamber orchestra and tape,

Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, Dennis Russel Davies – Conductor,

Vasiko Tevdorashvili – Voice,

Natalia Pschenitschnikova – Alto Flute.

for chamber orchestra and tape,

Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, Dennis Russel Davies – Conductor,

Vasiko Tevdorashvili – Voice,

Natalia Pschenitschnikova – Alto Flute.

Manorexia – Canaries in the Mineshaft (2011)

Live at the Whitney Museum NYC, as part of the JG Thirlwell Composer Spotlight.

JG Thirlwell- Laptop and compositions

Leyna Marika Papach – Violin

Elena Moon Park – Violin

Karen Waltuch – Viola

Felix Fan – Cello

David Broome – Piano

David Cossin – Percussion

Leyna Marika Papach – Violin

Elena Moon Park – Violin

Karen Waltuch – Viola

Felix Fan – Cello

David Broome – Piano

David Cossin – Percussion

Filmed and edited by Jeff Davidson

Arseny Avraamov – Symphony Of Factory Sirens (1922)

Arseny Avraamov – Symphony Of Factory Sirens (Public Event, Baku 1922)

Arseny Mikhailovich Avraamov (born Krasnokutsky, 1886, died Moscow, 1944) was an avant-garde Russian composer and theorist. He studied at the music school of the Moscow Philharmonic Society, with private composition lessons from Sergey Taneyev. He refused to fight in World War I, and fled the country to work, among other things, as a circus artist. Returning in 1917, he went on to compose his famous “Simfoniya gudkov” and was a pioneer in Russian sound on film techniques. Among his other achievements were the invention of graphic-sonic art, produced by drawing directly onto magnetic tape, and an “Ultrachromatic” 48-tone microtonal system, presented in his thesis, “The Universal System of Tones,” in Berlin, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart in 1927. His microtonal system predated the creation of the Petrograd Society for Quarter-Tone Music in 1923, by Georgii Rimskii-Korsakov.Today, his most famous work is Simfoniya gudkov (Гудковая симфония, “Symphony of factory sirens”). This piece involved navy ship sirens and whistles, bus and car horns, factory sirens, cannons, the foghorns of the entire Soviet flotilla in the Caspian Sea, artillery guns, machine guns, hydro-airplanes, a specially designed “whistle main,” and renderings of Internationale and Marseillaise by a mass band and choir. The piece was conducted by a team of conductors using flags and pistols. It was performed in the city of Baku in 1922, celebrating the fifth anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution, and less successfully in Moscow, a year later. [source]“By knowing the way to record the most complex sound textures by means of a phonograph, after analysis of the curve structure of the sound groove, directing the needle of the resonating membrane, one can create synthetically any, even most fantastic sound by making a groove with a proper structure of shape and depth”.From “Upcoming Science of Music and the New Era in the History of Music” by Avraamov, published in 1916.

Arsenij Avraamov conducting “Symphony of the Factory Sirens” using two flaming torches (c.1923)

Franz Schubert – Ave Maria (1825)

“Ellens dritter Gesang” (Ellens Gesang III, D. 839, Op. 52, No. 6, 1825), in English: ”Ellen’s Third Song”, was composed by Franz Schubert in 1825 as part of his Opus 52, a setting of seven songs from Walter Scott´s popular epic poem The Lady of the Lake, loosely translated into German.It has become one of Schubert’s most popular works, recorded by a wide variety and large number of singers, under the title of Ave Maria, in arrangements with various lyrics which commonly differ from the original context of the poem. It was arranges in three versions for piano by Franz Liszt. [source]

Maria Callas – Vocal / Unknown – Piano

[Dedicated my father, who died in Tanzania 07.04.1995. Rest in peace]

Sofia Gubaidulina – The Canticle of the Sun (1997, rev. 1998)

Glorification of the Creator, and His Creations – the Sun and the Moon

Glorification of the Creator, the Maker of

the four elements: air, water, fire and earth

Glorification of life

Glorification of death

Glorification of the Creator, the Maker of

the four elements: air, water, fire and earth

Glorification of life

Glorification of death

Sofia Gubaidulina’s 80th birthday in October 2011 generated much press coverage around the world, appropriately stressing the uniqueness and the variety of her compositional approaches. Both are in evidence on these recordings from Lockenhaus. “Canticle of the Sun”, recorded in 2010, revisits the celebrated piece that Gubaiduilina wrote in tribute to Mstislav Rostropovich on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1997. Rostropovich’s famously sunny disposition was an inspiration, by association prompting Gubaidulina to set St Francis of Assisi’s “Canticle of the Sun” for choir. In this recording, Nicolas Altstaedt, one of the most accomplished cellists of his generation, takes on the highly expressive lead role. A further, timely, Lockenhaus connection here: as of this year, Altsteadt takes over from Kremer as the new director of the Lockenhaus Chamber Music Festival. [source]

Gidon Kremer: Violin

Marta Sudraba: Violoncello

Nicolas Altstaedt: Violoncello

Andrei Pushkarev: Percussion

Rihards Zalupe: Percussion

Rostislav Krimer: Celesta

Riga Chamber Choir Kamēr…

Māris Sirmais: Conductor

Marta Sudraba: Violoncello

Nicolas Altstaedt: Violoncello

Andrei Pushkarev: Percussion

Rihards Zalupe: Percussion

Rostislav Krimer: Celesta

Riga Chamber Choir Kamēr…

Māris Sirmais: Conductor

The Canticle of the Sun (1997, rev. 1998)

for violoncello, chamber choir, percussion and celesta

Dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich

Recorded July 2010 at Lockenhaus Festival

ECM Records New Series 2256

Genre: Classical

Style: Experimental, New Music, Post-Modern

for violoncello, chamber choir, percussion and celesta

Dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich

Recorded July 2010 at Lockenhaus Festival

ECM Records New Series 2256

Genre: Classical

Style: Experimental, New Music, Post-Modern

Canticle of the Sun revisits the celebrated piece that Gubaidulina wrote in tribute to Mstislav Rostropovich on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

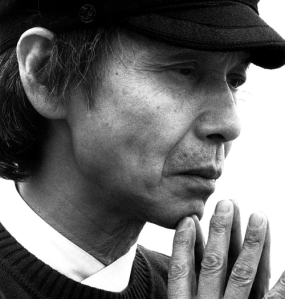

Tōru Takemitsu – Requiem for strings orchestra (1957)

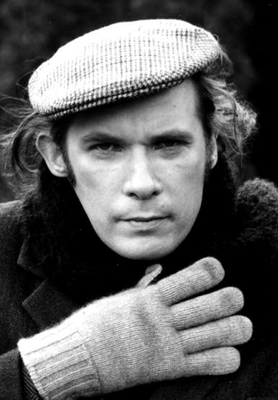

When Igor Stravinsky was introduced to Toru Takemitsu in 1959, he was taken aback by the young Japanese composer’s frail, slight frame. “How could such severe music come have come from such a tiny man?” he is said to have wondered aloud. Just prior to their meeting, the elder composer had happened upon a recording of Takemitsu´s haunting Requiem, a piece for string orchestra composed in 1957, when Takemitsu was just 27 years old. [source]Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996). His 1957 Requiem for strings orchestra attracted international attention, led to several commissions from across the world and established his reputation as one of the leading 20th century Japanese composers. He was the recipient of numerous awards and honours and the Toru Takemitsu Composition Award is named after him.[source]

Toronto Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Seiji Ozawa

[Inspired by Ronnie Rocket, thanks a lot]

Carl Nielsen – Wind Quintet op. 43 (1922)

Carl Nielsen´s Wind Quintet or, more correctly, the Quintet for Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, French Horn and Bassoon, Op. 43, was composed early in 1922 in Gothenburg, Sweden, where it was first performed privately at the home of Herman and Lisa Mannheimer on 30 April 1922. [source]

Scandinavian Chamber Players:

Lars Graugaard – Flute

Ole-Henrik Dahl – Oboe

Hans Christian Bræin – Clarinet

Jens Tofte-Hansen – Bassoon

Henning Hansen – French Horn

Per Egholm – Alto Saxophone

Carsten Tagmose – Cello

Michael Dabelsteen – Double-Bass

Lars Graugaard – Flute

Ole-Henrik Dahl – Oboe

Hans Christian Bræin – Clarinet

Jens Tofte-Hansen – Bassoon

Henning Hansen – French Horn

Per Egholm – Alto Saxophone

Carsten Tagmose – Cello

Michael Dabelsteen – Double-Bass

Leoš Janáček – String Quartet No. 1, ‘Kreutzer Sonata’ (1923)

Leoš Janáček´s String Quartet No. 1, “Kreutzer Sonata”, was written in a very short space of time, between 13 and 28 October 1923, at a time of great creative concentration. The work was revised by the composer in the autograph from 30 October to 7 November 1923.The composition was inspired by Leo Tolstoy´s novella The Kreutzer Sonata. (The novella was in turn inspired by Beethoven´s Violin Sonata No. 9, known as the “Kreutzer Sonata” from the name of its dedicatee, Rodolphe Kreutzer)The première of the Quartet was given on 17 October 1924 by the Czech Quartet at a concert of the Spolek pro moderní hudbu (Contemporary Music Society) at the Mozarteum in Praque. A pocket score of the work was published in April 1925 by Hudební matice.Janáček also used the Tolstoy novel in 1908-1909 when it inspired him to compose a Piano Trio in three movements, now lost. Surviving fragments of the Trio suggest that it was quite similar to the surviving quartet, and reconstructions as a piano trio have been performed. [source]1. Adagio – Con moto2. Con moto3. Con moto – Vivo – Andante4. Con moto – (Adagio) – Più mosso

Leoš Janáček with his wife in 1881:

Alvin Lucier – I Am Sitting In A Room (1980)

I am sitting in a room is Alvin Lucier’s idea of pure sound experiments. Through playback and recording of successive generations of his own voice the sound is washed until his talking is a pure harmonic. The album starts with a relatively bland Lucier..”I am sitting in a room” but as the generations progress everything becomes a pure ambient. As Lucier suggests in the recording, this sound is the dynamic of the room he records in. It is released in two parts on well pressed vinyl.

“I am sitting in a room, different from the one you are in now.” So begins one of the masterpieces of 20th century music merging processed music, minimalism, and self-reference into an utterly amazing and ultimately beautiful work. The instructions for producing the piece are, in fact, the piece itself. The composer sits and describes what will happen, and then it happens. Lucier tapes these instructions (about 80 seconds worth), tapes it, replays that tape into the room, tapes that, plays the second tape into the room, etc., and so on. Little by little, the “natural resonant frequencies of the room” erode the source material, softening hard edges, blurring boundaries between words. Different rooms will, presumably, give different results depending on their individual architectural properties. After ten or 12 repetitions, the listener already has difficulty distinguishing individual words, though the rhythmic pattern remains. But, and this is one of the cruxes of the work, all is not entropy. As the text becomes indecipherable, elements of undeniably musical tones emerge from nowhere, as though they were embedded in the original speech and only came to light after the surface structure was eliminated. Indeed, small melodies can actually be heard and the effect is absolutely magical. Fifteen minutes into the composition, Lucier’s speech has become a hazy cloud of wavering, bell-like tones interrupted by the occasional sibilance, the latter generated by the composer’s stutter, which adds an element of poignancy to the piece’s conception. Halfway through, no aspect of the speech can be gleaned except a rough cadence; instead, the listener has been transported to a sound world at such a far remove from the initial text as to leave one both baffled and awash in wonder. I Am Sitting in a Room is a unique, extraordinary idea/composition, a landmark among late 20th century avant-garde music and a touchstone for a generation of composer/theoreticians. It’s a rare combination of sensual beauty and intellectual rigor, and should be heard by anyone interested in contemporary music. [source]

Side A. I Am Sitting In A Room Pt. I (21:50)

Side B. I Am Sitting In A Room Pt. II (23:10)

Side B. I Am Sitting In A Room Pt. II (23:10)

This record was made by the composer on October 29 and 31, 1980 in the living room of his home in Middletown, Connecticut. It consists of thirty-two generations of the composer’s speech and was made expressly for this Lovely Music record.

Alvin Lucier – Vocals

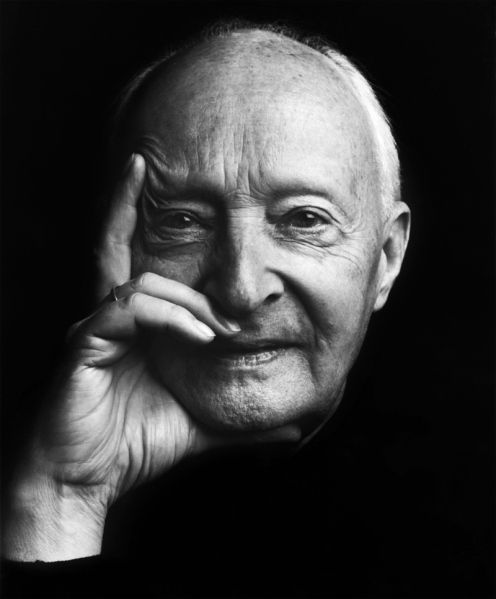

Conlon Nancarrow – Study for Player Piano 3a (1988)

From the album Studies For Player Piano by Conlon Nancarrow, recorded on Conlon Nancarrow’s custom-altered 1927 Ampico reproducing piano at the studio of the composer in Mexico City on January 10 and 12, 1988.

Conlon Nancarrow’s Studies for Player Piano is a cycle of work unique in many respects, not the least being its seeming indivisibility from itself. As the primary text of the music is a hand-punched piano roll intended to be played on specific, Ampico model player pianos, it does not lead to a wide range of options in terms of interpretation. Studies for Player Piano, stems from master tapes made in Mexico City for release on the 1750 Arch label in the 1970s and ’80s, with Nancarrow´s own specially retrofitted pianos, in Nancarrow´s studio, and with the composer himself picking tempos and working with producer Charles Amirkhanian to achieve ideal results. These recordings were considered state of the art at the time and still sound great, and can certainly be considered definitive; CDs drawing from sources made later represent the music as played back by other machines and operators. While the differences might be slight, they are still significant, particularly in regard to tempo choices, which can either make or break this music, and breaking it isn’t hard to do at all. Hearing them played back on Nancarrow´s pianos also affords an additional layer of articulation missing from many reproductions; one of Nancarrow´s pianos was fitted with metal hammers, resulting a clattery sense of attack, whereas the other had hammers covered with leather strips for a more mellow sound. Make no mistake about it: the Other Minds set truly represents what Nancarrow himself wanted you to hear when it came to his player piano music, and he did have very specific ideas about that. [source]

Conlon Nancarrow - Piano

Beethoven – Piano Sonatas (1795 – 1822)

Ludwig van Beethoven wrote his 32 piano sonatas between 1795 and 1822. Although originally not intended to be a meaningful whole, as a set they comprise one of the most important collections of works in the history of music. Hans von Bülow even called them “The New Testament” of music (Johann Sebastian Bach´s The Well-Tempered Clavier being “The Old Testament”.Beethoven’s piano sonatas came to be seen as the first cycle of major piano pieces suited to concert hall performance. Being suitable for both private and public performance, Beethoven’s sonatas form “a bridge between the worlds of the salon and the concert hall”.Camille Saint-Saëns, in his debut public recital at the age of ten, offered to play as an encore any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory.In a single concert cyclus, the whole 32 sonatas were first performed by Hans von Bülow; the first to make a complete recording was Artur Schnabel in 1927 (he was also the first since von Bülow to play the complete cycle in concert from memory). [source]

Glenn Gould – Piano

Igor Stravinsky – Ebony Concerto (1945)

Two different worlds united in one.

I. Moderato

II. Andante

III. Moderato

II. Andante

III. Moderato

Igor Stravinsky wrote the Ebony Concerto in 1945 for the Woody Herman band known as the First Herd. It is one in a series of compositions commissioned by the bandleader/clarinetist featuring solo clarinet. Herman recorded the concerto in the Belock Recording Studio at Bayside New York, calling it a “very delicate and a very sad piece”. Stravinsky felt that the jazz musicians would have a hard time with the various time signatures. Saxophonist Flip Phillips said “during the rehearsal [...] there was a passage I had to play there and I was playing it soft, and Stravinsky said ‘Play it, here I am!’ and I blew it louder and he threw me a kiss!” [source]

Woody Herman Orchestra.

Igor Stravinsky, conductor.

Recorded in 1946.

Columbia 78rpm disc 7479-M (XCO 36778; XCO 35779).

Digital Transfer by F. Reeder

Igor Stravinsky, conductor.

Recorded in 1946.

Columbia 78rpm disc 7479-M (XCO 36778; XCO 35779).

Digital Transfer by F. Reeder

[Happy Valentinesday]

Anton Webern – Six Bagatelles for String Quartet, Op. 9 (1911-13)

Webern’s Six Bagatelles for string quartet, Op. 9 (1911-13) represent a critical step for the evolution of atonal musical techniques. They also mark a critical step for the composer, who in his attempt to realize the ideas of his mentor, Arnold Schoenberg, emerged as a true original. For several years, Webern had doted on Schoenberg personally and artistically. When Schoenberg wrote his Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19, in 1911, Webern noted that some of the movements lacked contrast. While Schoenberg apparently gave little thought to the implications of his new work, Webern wrangled with this problem of contrast in the still-emerging language of atonality. Later that year, Webern wrote the internal movements of Op. 9, considering the result as his second string quartet.In the following year Webern followed Schoenberg to Berlin, where the revered master composed his epochal Pierrot Lunaire, which featuring the Sprechstimme (song-speech) technique. Webern presently composed three movements for string quartet, the second of which featured a Sprechstimme setting of his own poetry. Schoenberg, who had composed a string quartet with the addition of soprano in 1908, was no doubt painfully aware that Webern was in danger of becoming a faceless copycat. Schoenberg’s response was to not comment on Webern’s new work at all. Hurt and dismayed, Webern eliminated the Sprechstimme movement and used the two remaining movements to bookend his second string quartet.Schoenberg was very pleased with the result and even provided a glowing preface for its publication.The Six Bagatelles require about five minutes to perform. One difference between Op. 9 and Webern’s previous quartet, Op. 5, is that the earlier work contains movements built from sections and contrasts — in that sense, much in the spirit of Haydn. However, the movements of its successor are through-composed, not sectional, and there are no contrasts that require resolution. The level of musical tension is, nonetheless, very high; the work achieves this effect because the material in the first two measures provides ample opportunity to highlight and juxtapose individual musical gestures, and the dramatic envelope is controlled by the density of such activity.Alban Berg attempted a similar approach in his Four Pieces for clarinet and piano, Op. 4, but Schoenberg felt that Webern was more suited to this particular challenge and persuaded Berg not to pursue this compositional direction. Even Webern himself managed to carve out only two more works in this manner (Opp. 10 and 11) before he exhausted its possibilities. With this trio of works, however, he made a lasting impression upon the keener listeners of his day, and the Six Bagatelles remain among the strangest and most compelling aphorisms in the string quartet repertoire. [source]

Mässig

Leicht bewegt

Ziemlich fliessend

Sehr langsam

Ausserst langsam

Fliessend

Juilliard String Quartet (Recorded in New York 1970)

Emerson String Quartet (Recorded in New York 1992)

Lasalle String Quartet (Recorded 1968)

Anton Bruckner – Symphony No. 8 in C minor (1892)

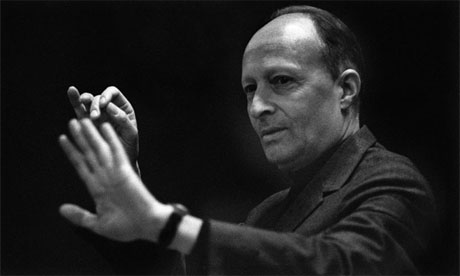

Recorded June 4th 1979, and filmed on location in the monastery church in St. Florian, Austria with Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

1st Movement.

2nd Movement.

3rd Movement.

4th Movement.

2nd Movement.

3rd Movement.

4th Movement.

Karajan later in an interview related that he was given special access to Bruckner’s underground tomb located beneath the great organ, where he was alone with Bruckner’s sarcophagus for a lengthy amount of time before the performance.

Anton Bruckner ’s Symphony No. 8 in C minor is the last Symphony the composer completed. It exists in two major versions of 1887 and 1890. It was premiered under conductor Hans Richter in 1892 in Vienna. It is dedicated to the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. This symphony is sometimes nicknamed The Apocalyptic, but – as with the nicknames The Tragic (for the Fifth Symphony), The Philosophic (for the Sixth), and The Lyric (for the Seventh) – this was not a name Bruckner gave to the work himself. [source]

Witold Lutosławski – Partita For Violin And Orchestra (1984 – 1988)

Partita For Violin And Orchestra was composed by Witold Lutosławski from 1984 to 1988 and was dedicated to the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. The premiere was 10 January 1990, Munich: Anne-Sophie Mutter, Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Witold Lutosławski.

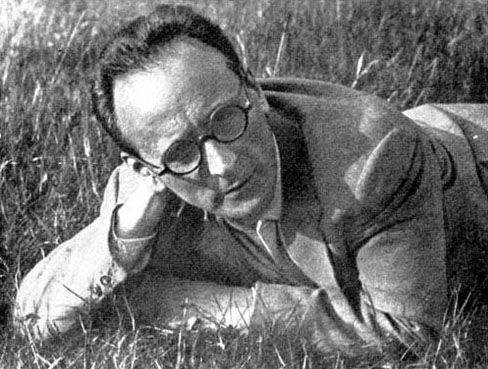

Witold Lutosławski ( January 25, 1913 – February 7, 1994) was a Polish composer and conductor. He was one of the major European composers of the 20th century, and one of the preeminent Polish musicians during his last three decades.Through the mid-1980s, Lutosławski composed three pieces called Łańcuch (“Chain”), which refers to the way the music is constructed from contrasting strands which overlap like the links of a chain. Chain 2 was written for Anne- Sophie Mutter (commissioned by Paul Sacher), and for Mutter he also orchestrated his slightly earlier Partita for violin and piano, providing a new linking Interlude, so that when played together the Partita, Interlude and Chain 2 form his longest work. [source]

1. Allegro Giusto (4:14)

1. Ad Libitum (1:12)

3. Largo (6.23)

4. Ad Libitum (0:47)

5. Presto (3.52)

1. Ad Libitum (1:12)

3. Largo (6.23)

4. Ad Libitum (0:47)

5. Presto (3.52)

Witold Lutosławski - Conductor

Phillip Moll – Piano

Anne-Sophie Mutter - Violin

BBC Symphony Orchestra

Phillip Moll – Piano

Anne-Sophie Mutter - Violin

BBC Symphony Orchestra

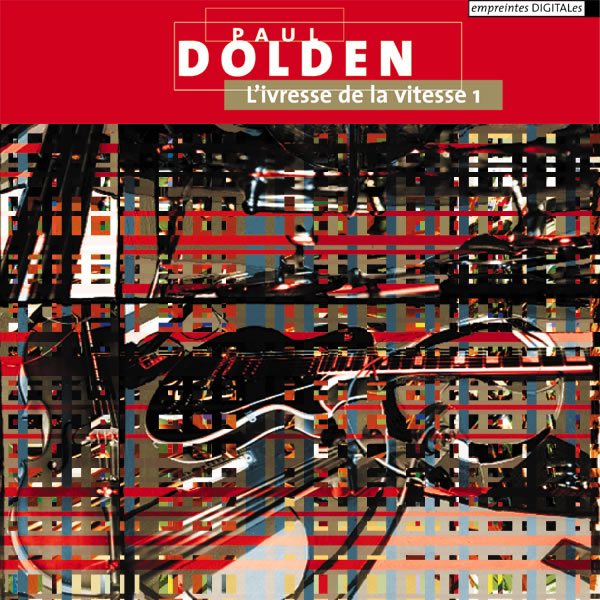

Paul Dolden – L’Ivresse De La Vitesse (1992-93)

L’Ivresse De La Vitesse is from the album L’Ivresse De La Vitesse by Paul Dolden. This amazing mix of real instuments and tape recordings is beyond all limits of genres.

Culling material that covers a decade of work, L´Ívresse de la Vitesse (Intoxicated by Speed) had the effect of a bomb in musique concrète circles. Paul Dolden´s previous album, The Threshold of Deafening Silence (1990), already indicated that the composer eschewed traditional tape music esthetics, but this ambitious two-CD set consecrated him as a new voice. Dolden works with instruments. His compositions are amalgams of partitions, hundreds of them, recorded individually on a wide array of instruments. They are later assembled through pitch, polyrhythmic and textural relations to create high-density pieces that seem to be performed by massive lunatic orchestras. At the heart of the album are three such pieces: “Dancing on the Walls of Jericho,” “Beyond the Walls of Jericho” (these two completing a triptych started on the previous CD with “Below the Walls of Jericho”), and the title piece. The three works in the “Invocation” series feature tape parts from the Jericho cycle over which a solo part has been added. Performers include Dolden himself on guitar, Vivenne Spiteri on harpsichord, and cellist Peggy Lee; they are simply beautiful in “Physics of Seduction: Invocation #2.” The same method is applied to the title track, transformed into the two parts of the “Resonance” series, both performed by François Houle (on soprano saxophone and clarinet). An older piece, “Veils,” concludes the set with a look at the emergence of Dolden’s technique as it is made of acoustic parts and more conventional musique concrète treatments. The energy, richness, and density of the music bring to mind the Vancouver new music big bands NOW Orchestra and Hard Rubber Orchestra — that is to say that it conveys a much more organic experience than more standard tape music. Decadent and subversive, L’Ivresse De La Vitesse is a classic, a unique form of fin de siècle tape music. [source]

Paul Dolden- Electric Guitar, Tapes / Francois Houle – Clasinet, Saxophone

Kimmo Hakola – Capriole for Bass Clarinet and Cello (19??)

Capriole for Bass Clarinet and Cello composed by Kimmo Hakola.

Kimmo Hakola is a Finnish composer born in 1958 in Jyväskylä. He studied composition with Einojuhani Rautavaara and Magnus Lindberg. He first came to prominence with his first String Quartet of 1986. [source]

Shinsuke Hashimoto - Bass Clarinet / Martin Stanzeleit - Cello

Live recording from Hiroshima Feb.9.2007.

Paul Hindemith – Symphonie “Mathis der Maler” (1934)

Symphony: Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter) is among the most famous orchestral works of German composer Paul Hindemith. The symphony is based on themes from Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler, which concerns the painter (in German, “Maler”) Matthias Grünewald (or Neithardt). Hindemith composed the symphony in 1934, before he had completed work on the opera. The conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler asked him at that time for a new work to perform on an upcoming Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra concert tour, and Hindemith decided to use themes from the opera in a symphony as a ‘trial run’ for the music. Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic gave the first performance on March 12, 1934. The first performance outside Germany was given by the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra in October 1934, conducted by Otto Klemperer. Other performances include the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra in 1936, conducted by Daniel Sternberg. The symphony was well received at its first performances, but Furtwängler faced severe criticism from the Nazi government for performing music that seemed to oppose party ideology. Hindemith completed the full opera by 1935 but, because of the political climate, its premiere was delayed until 1938 in Zürich, Switzerland.

Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini in Boston March 29, 1974:

[via Zdenka Pregelj on Google+]

Halim El-Dabh – Wire Recorder Piece (1944)

Wire Recorder Piece also called The Expression of Zaar is recorded in 1944. From the CD album Crossing Into The Electric Magnetic, by Halim El-Dabh, released on Halim El-Dabh Music LLC in 2000 .

Halim Abdul Messieh El-Dabh (Arabic: حليم عبد المسيح الضبع (Ḥalīm ʻAbd al-Masīḥ al-Ḍabʻ); born March 4, 1921) is an Egyptian-born American composer, performer, ethnomusicologist, and educator, who has had a career spanning six decades. He is particularly known as an early pioneer of electronic music, for having composed in 1944 the first piece of electronic tape music, specifically an electroacoustic musique concréte piece, and later for his influential work at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center from the late 1950s to early 1960s.It was while he was still a student in Cairo that he began his experiments in electronic music. El-Dabh first conducted experiments in sound manipulation with wire recorder there in the early 1940s. By 1944, he had composed the first piece of electronic tape music or musique concréte, called The Expression of Zaar, pre-dating Pierre Schaeffer´s work by four years. [source]

Tōru Takemitsu – Distance de fée (1951)

“Distance de fée” created in 1951, one of the best pieces of Takemitsu’s early period. The spirit of Debussy and Messiaen are fully felt in this work of approximately 7 and 1/2 minutes duration. Messiaen’s octatonic scale is used in the tonal language. The opening lyrical theme is repeated several times, and finds a new pathway upon each return – this is a version of variation as well as rondo form, two of Takemitsu’s favorite compositional procedures. This piece, like many others by Takemitsu, was inspired by poetry, in this case, a poem of the same title by Shuzo Takiguchi (1903-1979). This work describes, with lightly mythological imagery, an elusive, transparent creature living in “air’s labyrinth … it lives in the spring breeze That barely resembled the balance of a small bird” source

Arisa Fujita – Violin / Megumi Fujita – Piano

From the album Between Tides and Other Chamber Music with compositions by Toru Takemitsu, with Fujita Piano Trio, released in 2001.

Another excellent recording with unknown performers:

Witold Lutosławski – Mi-Parti (1976)

Mi-Parti is an orchestral work by Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, written in 1976 to a commission from the City of Amsterdam for the Concertgebouw Orchestra. The name broadly means in two parts, and is in accordance with Lutosławski’s preference for two-part structures during the 1960s to 1970s: a preparation part, and a main body with development and climax (this is most clearly demonstrated in his Symphony No. 2). [source]

Composed and Conducted by Witold Lutoslawski.

Recorded in 1976 with The Polish Radio National Symphony Orchestra, at Studios of Polish Radio & TV, Katowice.

Recorded in 1976 with The Polish Radio National Symphony Orchestra, at Studios of Polish Radio & TV, Katowice.

From the EMI-album: Lutosławski* : Polish Radio N.S.O.*, Lutosławski* – Concerto Per Orchestra · Jeux Vénitiens · Livre Pour Orchestre · Mi-parti

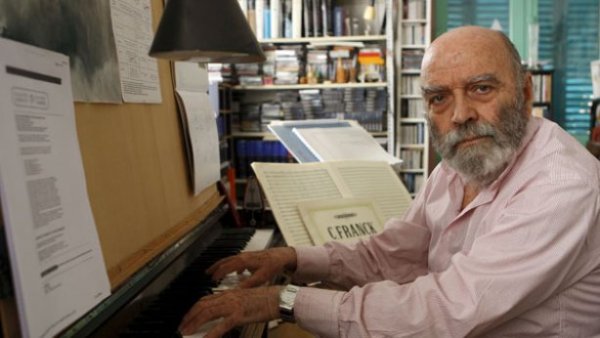

Luis de Pablo – Chamber Concerto (1979)

Luis de Pablo (born 28 January 1930) is a Spanish composer born in Bilbao, but after losing his father in the Spanish Civil War, he went with his mother and siblings to live in Madrid from age six. Although he started to compose at the age of 12, his circumstances made it impossible to consider an artistic career, and so he studied law at the Universidad Complutense. For a short time after graduating in 1952, he was employed as legal advisor toIberia Airlines, but soon resigned this post in order to pursue a career in music. Although he received composition lessons from Maurice Ohana and Max Deutsch, he was essentially an autodidact in composition. His participation at the Darmstadt courses in 1959 led to the performance of some of his works under Pierre Boulez and Bruno Maderna (Heine 2001). He was awarded Spain’s Premio Nacional de Música for composition in 1991. In Spain, he founded several organizations: Nueva Música, Tiempo y Música, and Alea and organized several contemporary music concert series, for example, the Forum Musical and Bienal de Música Contemporánea de Madrid. He was particularly concerned with promoting understanding in Spain of the Second Viennese School, publishing translations of Stuckenschmidt’s biography of Arnold Schoenberg in 1961, and the writings of Anton Webernin 1963 (Heine 2001). He is much in demand as a teacher, both in Spain and internationally.

Jos Kunst – Insecten (1966)

Joseph Petrus Johannes Maria (Jos) Kunst (Roermond, 3 January 1936 – Utrecht, 18 January 1996) was a Dutch composer and musicologist. Art grew up in Maastricht and studied French literature at the University of Groningen. On his 27th birthday he began studying music at the Conservatory of Amsterdam, successively by Joep Straesser and Ton de Leeuw. Besides his activities as a composer and as a French teacher, he was working as a lecturer in contemporary music and composition at the conservatories of Zwolle and Amsterdam. At the International Gaudeamus Competition in 1967 he received the AVRO-incentive for the piece Insects for 13 strings. Two years later, at the Gaudeamus Competition for 1969, he won the first prize with the orchestral work Arboreal. His main musical inspiration in the period up to 1975 were Anton Webern, Edgar Varèse and Iannis Xenakis. In 1975 he decided to stop composing. In 1976 he succeeded Rudolf Escher as teacher for the music of the twentieth century at the Department of Musicology of the University of Utrecht. As a musicologist he kept mainly concerned with what is called ‘cognitive musicology’: music science that seeks to describe what music does to the listener. Main musicological publications: Making sense in music: an Enquiry into the formal pragmatics of art (Dissertation, 1978), Philosophy of musicology (Martinus Nijhoff, 1988). In addition to his scientific work, he was active as a poet: he published poems in a Dutch monthly magazine in the years 1979-1988 and in 1982 appeared in the Meulenhoff compilation Nobody Will Ever Own. In 1988, he made use of the possibility to retire early. From that time he wrote again, but kept to himself, unlike in the past, and as much as possible outside the organized musical life. In this period, Claude Debussy was an important source of inspiration. Jos Kunst died at age 60.

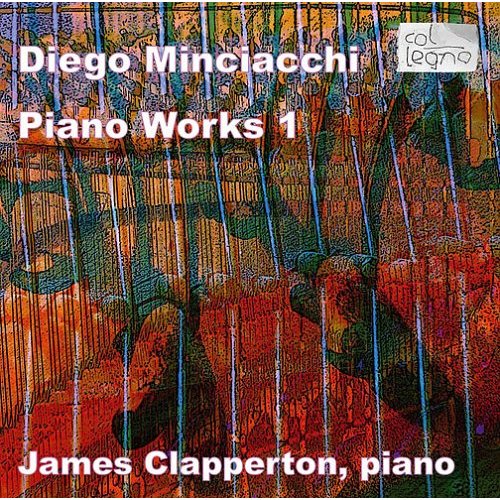

Diego Minciacchi – Klavierstück Nr.3 – Cockamamey (1990)

Composer and neurologist Minciacchi has ambitions. Three piano pieces (Nos. 1, 2 and 4) reflect the Roman’s ongoing “dialog” with his native city. Unfolding steadily, the Intermezzo’s tonal contours create unresolved tension. Three Times Form casually plies Darmstadt concerns, whereas Vae Victis ups the ante, interspersing passionate action between Scelsian single-pitch reverberations. Pianist Clapperton compares the complex La connessione disumana (No. 6) to Xenakis’ Evryali, but nothing prepares us for COCKAMAMEY’s (No. 3) five-piano density wherein minimalist shenanigans grind against postwar chatter, here recorded by Curtis Roads, whose mixing has the pianos traveling back and forth across the soundstage. Minciacchi’s works with tape prove more compelling, as an alternate Vae Victis with tape and live electronics shows. [Source]

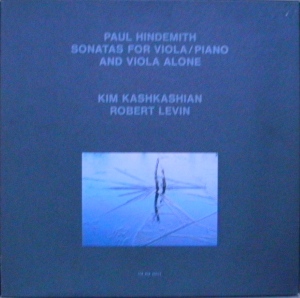

Paul Hindemith – Sonata for viola and piano in F major, Op.11, No.4 (1919)

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963). Hindemith is among the most significant German composers of his time. His early works are in a late romantic idiom, and he later produced expressionist works, rather in the style of early Arnold Schoenberg, before developing a leaner, contrapuntally complex style in the 1920s. This style has been described as neoclassical, but is very different from the works by Igor Stavinsky labeled with that term, owing more to the contrapuntal language of Johann Sebastian Bach and Max Reger than the Classical clarity of Mozart. [source]

1. Phantasie (3:06)

2. Thema mit Variationen (4:01)

3. Finale mit Variationen (10:09)

2. Thema mit Variationen (4:01)

3. Finale mit Variationen (10:09)

Kim Kaskashian – Viola

Robert Levin – Piano

Robert Levin – Piano

From: Paul Hindemith – Kim Kashkashian – Robert Levin - Sonatas For Viola And Piano And Viola Alone, released in 1988.

Jesús Rueda – Ítaca (1996)

Jesús Rueda Azcuaga (born in Madrid, 30 May 1961) is a Spanish composer. He won the 2004 National Prize for the global quality of his music, with special recognition to his recently premiered symphonic and chamber compositions, such as his Symphony No. 2 and his String Quartet No. 3. His Symphony No. 3, Viaje imaginario (dedicated to his teacher Francisco Guerrero following his untimely death) and a selection of his piano music, including his two sonatas, were subsequently published by Naxos Records.Through his career he has evolved from experimental music to a more mainstream style.He is the resident composer of the Cadaqués Orchestra, and a regular juror of the Queen Sofía Prize. [source]

Ananda Sukarlan – Piano / Proyecto Gerhard Ensemble / José de Eusebio – Direction

Toshio Hosokawa – Vertical Time Study III (1994)

Toshio Hosokawa (細川 俊夫 Hosokawa Toshio, born 23 October 1955 in Hiroshima, Japan) is a Japanese composer of contemporary classical music Hosokawa studied with Yun Isang at the Berlin University of the Arts. Since 1998, Hosokawa has served as Composer-in-Residence at the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra. In 2004, Hosokawa became a guest professor at Tokyo College of Music. In 2001, Hosokawa became a member of Akademie der Künste, Berlin. [source]

Irvine Ardetti – Violin

Ichiro Nodairo – Piano

Ichiro Nodairo – Piano

Julio Estrada – Tres instantes – (1982)

Julio Estrada Velasco (born 10 April 1943) is a composer, theoretician, historian, pedagogue, and interpreter.Estrada was born in Mexico City, where his family had been exiled from Spain since 1941. He began his musical studies in Mexico from 1953–65, where he studied composition with Julián Orbón. In Paris from 1965-69 he studied with Nadia Boulanger, Olivier Messiaen and attended courses and lectures of Iannis Xenakis. In Germany he studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen in 1968 and with György Ligeti in 1972. He completed a Ph.D in Musicology at Strasbourg University from 1990-1994. [source]

Lylia Vásquez, – Piano /Álvaro Bitrán – Violoncello.

Grabada en la UAM-Iztapalapa, México, 1982.

Grabada en la UAM-Iztapalapa, México, 1982.

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar