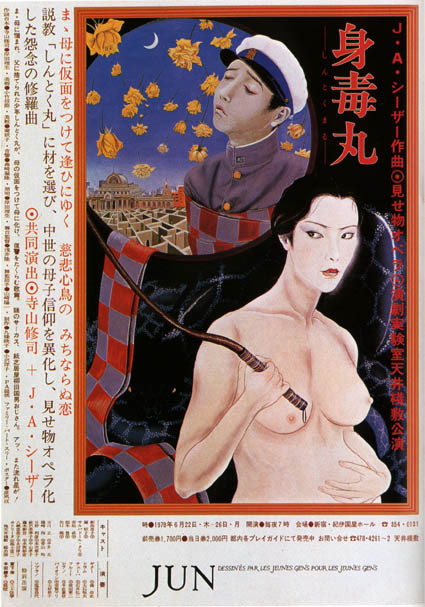

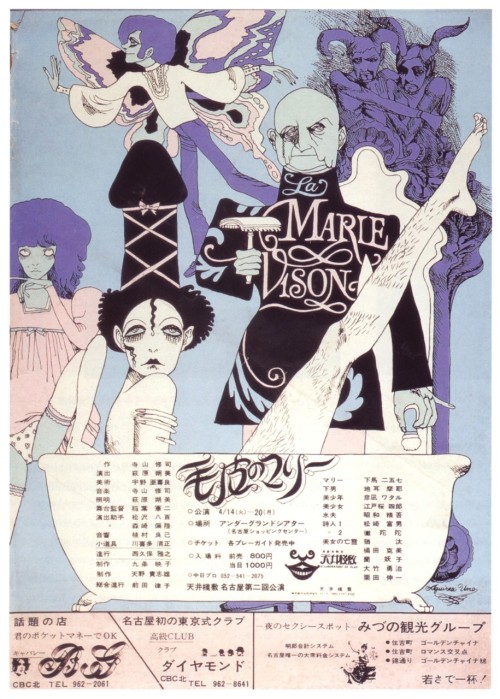

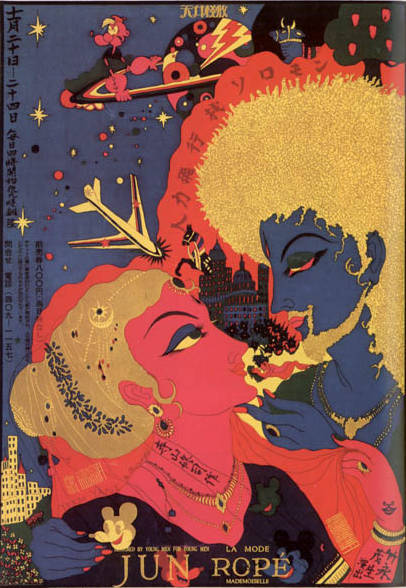

Posteri za predstave Terayamine kazališne skupine Tenjo sajiki.

The Spectacular, Wild World of Tenjo Sajiki and its Posters

WRITTEN BY WILLIAM ANDREWS

Playwright, director, poet, novelist, provocateur: Shuji Terayama (1935-83) was a multi-faceted artist and a leader — perhaps THE leader — of the underground theatre scene (angura) in Japan during the Sixties and Seventies. Probably best known in the West as an experimental film director, Terayama was the head of a iconoclastic and often controversial troupe called Tenjo Sajiki. The name literally means “upper balcony” but comes from the Japanese title for the Marcel Carné film ‘Les enfants du paradis’.

Terayama was really different. He was heavily influenced by European artists and he always seemed to go one step further than his counterculture peers. His theatrical projects and films employed a host of shocking images, mixing taboos, the grotesque, all thrown together in a cheeky, playful way. Tenjo Sajiki’s frequently employed subtitle translates as “experimental theatre laboratory”. Terayama was part magician and part scientist, concocting scandals and freak shows.

[Left] Poster for German performance of ‘Der Gott der Hunde’ (Inugami, The Dog God) (1969), Kiyoshi Awazu, silkscreen. At the time, this was the first overseas production by a contemporary Japanese theatre troupe and Awazu’s poster emphasizes the exotic.

[Right] Poster for ‘The Little Prince’ (Hoshi no ouji-sama) (1968), Aquirax Uno, silkscreen

[Right] Poster for ‘The Little Prince’ (Hoshi no ouji-sama) (1968), Aquirax Uno, silkscreen

The posters for Tenjo Sajiki’s productions reflect this anarchic atmosphere. Currently running at Poster Hari’s Gallery is an exhibition of all the major performance posters by the troupe. It is part of a series of celebrations for Terayama: this year marks thirty years since his death, plus the fortieth anniversary of Parco’s opening in Shibuya, whose theatre early on hosted Tenjo Sajiki’s work. Parco recently held a mini Terayama “film poetry exhibition” and some of his films have also just been released on Blu-ray. The current production at the Parco Theater is a revival of ‘Lemming’, a play from Terayama’s late period. Even Tower Records is getting in on the act; Shibuya Station’s Yamanote Line platform features a famous image of the playwright as part of the retailer’s ‘No music, no life’ advertising series.

Poster Hari’s is a small gallery in Dogenzaka, Shibuya. Its name comes from haru, to put up a poster, so not surprisingly the company handles posters and such advertising for theatre companies. It started up just as Terayama died, depriving the CEO of his dream to join Tenjo Sajiki. Luckily, at the same time, with the growth of commercial theatre in Japan, posters started to be handled by outside PR firms rather than individual designers attached to troupes, as was the case for theangura era. The perfect moment to start a poster design company.

[Left] Poster for ‘Shuji Terayama & Tenjo Sajiki: All Posters’ Exhibition at Poster Hari’s Gallery

[Right] Poster for Parco’s recent Shuji Terayama ‘film poetry exhibition’

[Right] Poster for Parco’s recent Shuji Terayama ‘film poetry exhibition’

Poster Hari’s Company works with Terayama’s widow to archive Tenjo Sajiki’s output and other posters from the angura period. It also handles the maintenance now of the Shuji Terayama Museum in Aomori, as well as managing the rights to productions of Terayama’s plays through the Terayama World company. Every May at around the anniversary of Terayama’s death it holds a poster exhibition, though this time, being three decades since the artist died, the event is more ambitious, showcasing around forty posters of Tenjo Sajiki productions, including some unusual examples from overseas performances that were likely done by local designers.

The current exhibition is just the theatre posters, though it is packed with iconic work by the likes of Tadanori Yokoo, Kiyoshi Awazu and Aquirax Uno. Theatre posters today are rarely this big and will normally feature photographs of the stars, as opposed to such striking graphics. Fringe theatre now favors flyers and leaflets, which can be distributed to lots of people. Tokyo has always had limited wall space and it is only in a place like Shimokitazawa that you can find lots of theatre posters decorating the streets as both advertising and a form of public art.

[Left] Recruitment poster for Tenjo Sajiki by Tadanori Yokoo (1967), silkscreen. Note the snake-charmer in the bottom right and the sinking ship on the horizon. ‘Jun’ is an advertisement for a retail chain that sponsored Tenjo Sajiki.

[Right] Poster for ‘Throw out your books, head out to the streets’ (Sho o suteyo! machi e deyo!’) (1969), Masamichi Oikawa, silkscreen. This is the poster for the original theatre ‘docudrama’ that then became an influential experimental film. The black armbands signify a funeral, the youth throwing out their old lives and escaping from their bonds.

[Right] Poster for ‘Throw out your books, head out to the streets’ (Sho o suteyo! machi e deyo!’) (1969), Masamichi Oikawa, silkscreen. This is the poster for the original theatre ‘docudrama’ that then became an influential experimental film. The black armbands signify a funeral, the youth throwing out their old lives and escaping from their bonds.

Even before you know anything about Tenjo Sajiki you have probably already seen the posters somewhere. Just as angura was diverse, radical and multi-dimensional, so too were the posters. In contrast to the postwar style which had been mostly simple, flat and asymmetrical, these new graphics are totally wild. Up to the late Sixties poster design in Japan tried to keep a deliberately “international” look that avoided anything too “Japanese”, sticking with sans serif font. (For example, compare the posters for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 with Tenjo Sajiki posters!)

But the new generation of designers wanted to be irrational, absurb, erotic and free. Anguraprovided them with the perfect opportunity to vent their talents. Yokoo was the leader, introducing pop art to the scene, and working prolifically, such as with Juro Kara (another theatre artist from the time), film director Nagisa Oshima (see Yokoo’s great poster for ‘Diary of a Shinjuku Thief’), and Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata.

Awazu takes more of a collage approach, while Uno is as colorful as Yokoo, though perhaps more erotic. The posters were mostly made by silk-screening and often the work would be done for gratis as budgets in the angura world were very limited. In spite of these strictures, the results were never anything less than grand, silk screen posters on full press sheets, 30 x 40 inches. The posters would be printed in limited runs of around 300, with maybe sixteen or more colors, and the stenciling done by the designers themselves.

They indulge in pastiche — as did the productions — and frequently employ kantei font and ukiyoemotifs. These elements are reminiscent of “Edo” but not a full imitation, just as Tenjo Sajiki et al were taking performance back to the world of outcasts and renegades, where Kabuki had originally sprung from.

As wall space was so limited, no matter how magnificent, the final Tenjo Sajiki poster might find itself just put up at the theatre or in a trendy coffee shop, perhaps even relegated to a toilet. This exhibition restores some respectful sense of “artwork” status to them. In fact, it was frequently the case that angura posters failed as advertising, not least because the hectic nature of the troupes meant the posters often arrived late or at the last minute. They were rather works of art in themselves and reflections of the atmosphere of the groups.

[Left] Poster for 1982 production of ‘Lemming’, designed by Tsutomu Toda, painted by Sawako Gota

[Right] Poster for Parco revival of ‘Lemming’ (2013), Gaku Azuma

[Right] Poster for Parco revival of ‘Lemming’ (2013), Gaku Azuma

The new revival of ‘Lemming’ is directed by Yukichi Matsumoto, the veteran Osaka director known for his Ishinha company. He collaborates with Gaku Azuma, the Osaka artist who was influenced by Uno and Yokoo, but till he started making theatre posters for Ishinha had focused on painting mainly images of feminine waif figures with sumi (charcoal) and a calligraphy brush. His poster for ‘Lemming’ (a fantastic Tower of Babel) is the first time he has painted a building. The original painting will also be exhibited at Poster Hari’s Gallery in July, along with other artworks by Azuma.

There has actually recently been a large resurgence in interest in postwar Japanese experimental arts, including several academic studies and not least, the mammoth MoMA exhibition last year,‘Tokyo: 1955-1970, A New Avant-Garde’. In particular, these are boon years for Shuji Terayama. Terayama’s reputation has been bolstered in Japan and abroad, with numerous productions and revivals of his work, as well as the Shuji Terayama Museum (opened in 1997) and even a showcase of his oeuvre at the Tate Modern in London in 2012.

This is not without problems. The commercialization and memorialization of Terayama essentially goes against what he and his group, and the angura counterculture movement of which he was one of the leaders, was trying to manifest — namely, to free up artistic spaces and expectations, and to run counter to the mainstream and the commercial. Now rather we have a Shuji Terayama who is alive in books, magazines, DVDs, catalogues — the paraphernalia of consumerism.

Terayama’s most famous work — a book, film and play — is ‘Throw out your books, head out to the streets’ (Sho o suteyo! machi e deyo!) but the new motto for the Terayama boom seems more to be “head into the shops, buy up the books”. And that the Shuji Terayama Memorial Museum should be built in Misawa in Aomori prefecture, admittedly his home region, is an irony considering that he arguably abandoned the north to work almost entirely as an urban artist in Tokyo and overseas. (The first production of Tenjo Sajiki was called ‘The Hunchback of Aomori’ in 1967.) This fact did not escape the locals, who either did not know of Terayama or regarded him unfavorably. Till recently a large proportion of the visitors was made up of people travelling up from Tokyo, but the management now holds free open days and other schemes to attract Aomori people to the museum.

Terayama died in 1983 at the age of just forty-seven, as opposed to his peers, many of whom are still working today. Since theatre is an ephemeral art form, his stage work has essentially now been lost, though thanks to his prodigious output of film, poetry and books, Terayama’s world still lives on. And perhaps there is no more accessible way to start than with Tenjo Sajiki’s posters. - pingmag.jp/2013/04/29/tenjo-sajiki-poster/

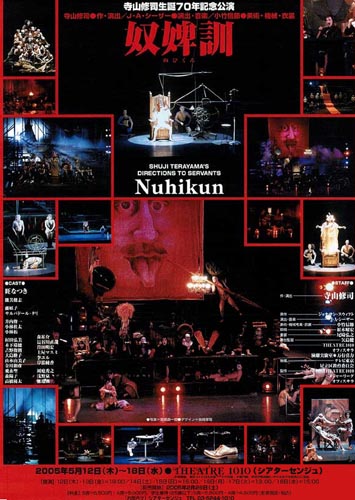

Directions to Servants (1978)(Tenjo Sajiki)(VHSRip)

I am quite thrilled to be able to share this piece: it was a lucky find on the Japanese P2P network Share. I've always dreamed of watching an actual Tenjo Sajiki production: the recent on-stage renditions of Terayama's plays seemed as watered down to me as they were glossed over. So, today, I finally got a chance to watch the real thing. The quality of this video recording is very low, but that's probably as much as we'll ever get. Obviously, there are no subtitles. From a few hints in various Internet sources, it seems that Tony Rayns may have translated Terayama's play into English at some point, but I have not been able to locate any references to the actual translation, nor am I sure if it has been published at all... Tenjo Sajiki rocks!!!

...it was interesting to see the acrobatic Japanese actors of the Tenjosajiki company in Shuji Terayama’s Directions to servants. The title and some of the text were taken from Swift’s satire, but the main inspiration seemed to come from Genet’s Les bonnes. Multiplying the maids into a large cast of servants, male and female, who take it in turns to imitate the master, Tereyama has physicalized and partly mechanized the action. Domination is imposed partly through machines—we see a man submitting to an imperious voice on a tape recorder, lowering his trousers and climbing inside a sadistic machine that beats his bare buttocks.

The ingenuity, the sadism and the offbeat humour are all characteristic of the production. The main cruelty to the audience was in the over-amplification of J.A. Seazer’s music. I sat with my hands over my ears for a lot of the time. The visual assault was almost equally strong, and some of the theatrical imagery was quite unlike anything that had been seen in this country. In one meticulously choreographed sequence the servant playing at being master throws a bone to a succession of servants who play at being dogs. In another, a servant trying to steal food from a cupboard is terrified to find that it is like a puzzle: each panel conceals a face that sings at him accusingly, and he can silence it only by sliding a panel that reveals another singing face.

(http://www.english.fsu.edu/jobs/num04/Num4Hayman.htm)

Sky Station Tenjyo Sajiki : Den'en Ni Shisu (JAP,1974)*****

Tenjyo Sajiki : Den'en Ni Shisu (JAP,1974)*****

" This is not really like they described this with a kind of "Magma weirdness" etc. The Uniqueness of this item lays in the highly emotional performance, much more than in any other Japanese item I heard before outside the dark song oriented music. This still is close to this song oriented scene, and from there it is highly original in its core. It is the most emotional Japanese item I know myself.

Track 11 has orgasmic choir and fuzz guitar, drums. The liner notes are completely in Japanese so I don't know the titles. Tenyo Sajiki was the theatre group of the an underground film-maker Shuji Terayama with the picked out of the street hippie J.A. Caesar as its composer. First and 6th track are children choir with drums, piano, electric bass, violin. Highly recommended to the (“naturally”) open minded. It's amongst my favourite Japanese releases. It’s a soundtrack to his 1974 film “Death In The Country”.

Described as a fictional autobiography, it tells of a sensitive adolescent poet who later becomes a film director, who dreams of running off first with a neighbour's wife and then with a travelling freakshow. The film follows a subtle subconscious logic. And it shows the search for the true self trough underlying emotions and desires of the main character. The performance was done by youngsters who suffered from the state’s pressure, and found herein a refoundation of their true inner nature of self-expression. More than just being reactive the music takes all valuable elements of the past and present and refocuses them into an renewed innocence and emotionally rich level. Because the theatre group had the impression of some kind of reactive refuge against a bourgeoning society in those days members were more than once interrogated. P.S. Folk singer Kan Mikami participated with an emotional singing."

"The early '70s in Japan are often painted as an era of political and artistic disillusionment. On the one hand, the state rode roughshod over widespread opposition by renewing a mutual security treaty with the US, forcibly purchasing farming land near Tokyo for the construction of a new airport and stamping down hard on student occupations of universities. In the face of the implacability of state power, the protest movements' fluffy dreams of peaceful revolution were viciously scalpel-sculpted into new and violent forms by Red Army hijackings, lynchings and hostage taking. The sense of confusion and lost innocence was further emphasized by teenage thrill killers, coin locker babies and the bizarre coup d'etat-cum-public suicide of novelist Yukio Mishima. Against this background Japanese youth music began to discard the perky Western imitations of the Group Sounds boom and the college folkies, and slide into more appropriately brutal forms of self expression. Folk turned angry and personal, while rock groups like Las Rallizes Denudes, Flower Travellin' Band and Keiji Haino's Lost Aaraaff discovered bad acid, dissonance and heavy electric blues.

Some of the most exciting and evocative music of the time, however, was born out of the avant garde theatre groups that had played such a central role in the '60s ferment. One of the most important was the Tenjo Sajiki Company (its name taken from Marcel Carne's wartime occupation fantasy Les Enfants Du Paradis), formed by poet, film maker, boxing fan and all-around agent provocateur, Shuji Terayama. Renowned for Living Theatre-inspired audience participation happenings and extreme street theatre designed to shock the bourgeois, by 1970 the group had already become a haven for runaway teens, and a focus for police investigation. Terayama was canny enough to realize that co-opting their music was an ideal way to hijack adolescent energies, and he consistently used heavy amplified rock to jump-start his chaotic, socially critical acid operas.

Heard today, even independent of their lyrical message, they're astonishingly powerful as pieces of music, deploying huge Magma choruses alongside juggernaut organ, guitar, bass, drums and fully out-there vocalizing. The pick of this bunch is the soundtrack to Terayawa's 1974 film Den-en Ni Shisu (Death In The Country). Described as a fictional autobiography, it tells of a sensitive adolescent poet who later becomes a film director, stuck with his neurotic mother in a rural northern backwater, who dreams of running off first with a neighbour's wife and then with a traveling freakshow. The film's fractured narrative of awakening sexuality and severing of parental bonds is captured in hallucinatory imagery and an equally ambitious soundtrack by J.A. Caesar, which binds the whole film together with a subtle, subconscious logic.

The deployment of disparate elements in an all-consuming flow, which works even independently of the images, is masterly. The familiar psych guitar, organ and choral chanting are heavy enough in places -- as on the disc's definitive reading of Caesar's massive and haunting 'Wasan' -- to approach Sabbath levels of dense pounding, and there's also a frighteningly visceral vocal turn from folk singer Kan Mikami. But the score also sees Caesar expanding his instrumental palette, scoring some tracks for sideshow brass band or gently plucked guitar, weeping violin and chant. The weird intervals of his sparse, medieval-influenced melodies linger in the memory with the force of nostalgia for a past not directly experienced. It's an amazing performance: from street hippy who'd never picked up an instrument to film soundtrack composer in five years. Caesar's soundtrack for Den-en Ni Shisu lost out by a single vote to Toru Takemitsu for the best film soundtrack of 1974." -- Alan Cummings, The Wire.

Audio here

Belle Antique

Tenjyo Sajiki (J.A.Caesar) : Shintokumaru (JAP,1976?)***°°

Tenjyo Sajiki (J.A.Caesar) : Shintokumaru (JAP,1976?)***°°

"A theatre piece which sounds like a combination of no theatre, orchestrated theatre music, opera and an outsider's rockconcert. Although the voices by actors are not always singing 100 % correct during the complete piece, it is too original to deny. The combination of elements, koto, operatic singing and heavy rock is at the best moments very impressive." - progressive.homestead.com/japanreviews2.html#anchor_69

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar