José Val del Omar (1904 – 1982),

španjolski filmaš, izumitelj i pjesnik, slabo je poznat a na fotografiji

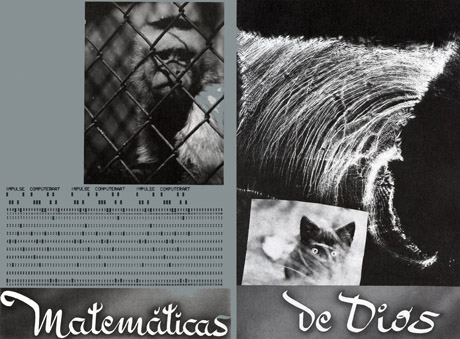

španjolske reprezentacije 20. stoljeća trebao bi biti negdje između Lorce i Buñuela. Zanimale su ga, između ostaloga, matematika boga i sveosjetilna umjetnost.

José Val del Omar (Granada 1904 - Madrid 1982) With an extraordinary artistic and technological talent, Val del Omar was a ''believer in cinema'' inspired by new horizons that he formulated in the term PLAT – representing the totalizing concept of a ''Picto-Luminic-Audio-Tactile'' art – apart from being a contemporary and a comrade of Lorca, Cernuda, Renau, Zambrano and other figures of a Silver Age of the Spanish culture, interrupted by the Civil War. In 1928 he anticipated various of his most characteristic techniques, including the ''apanoramic overflow of the image'' beyond the limits of the screen, and the concept of ''tactile vision''. These techniques. and those of ''diaphonic sound'' and other explorations in the field of electro-acoustics, would be applied in his Tríptico Elemental de España [Elementary Tryptich of Spain], begun in 1953 and only finished after his death. His work and tenacious research activity – quite against any tendency of misunderstanding and forgetfulness – did not begin to be rediscovered until shortly before his death, though it has constituted the beginning of a renaissance that continues to draw followers. ''Endless'', as he would put at the end of his films.

«I feel that Unity was my point of departure and is my point of return, I pass through a rainbow»

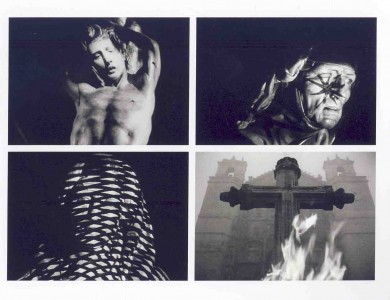

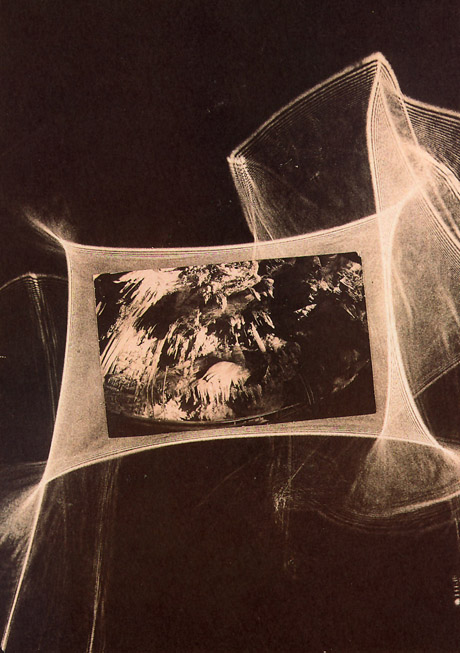

Fuego en Castilla (Fire in Castile)

Acariño galaico (Galician Caress)

'José Val del Omar (Granada, 1904-Madrid, 1982) cannot be pigeonholed, despite the fact that his deepest roots are in film. He belonged to a generation that believed in film as a full-fledged art, rather than as the new opiate of the people. Moreover, his ties to film are those of an outsider artist with very few works—at least, very few surviving works. A rarity in the context of Spanish filmmaking, which is hardly given to experimentation, he has gradually become a cult figure whose reputation and stature continue to expand.

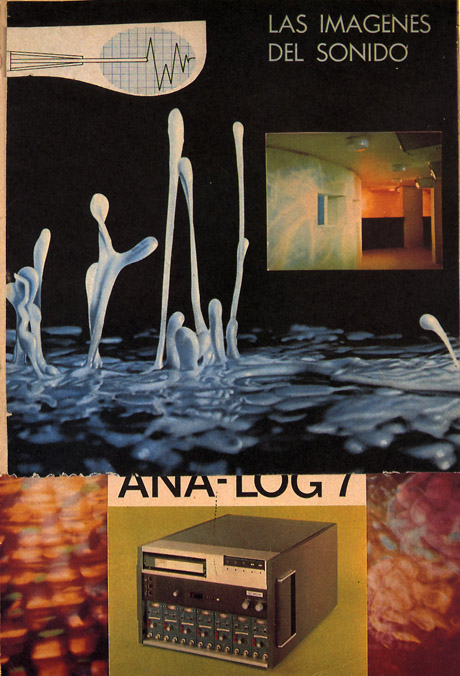

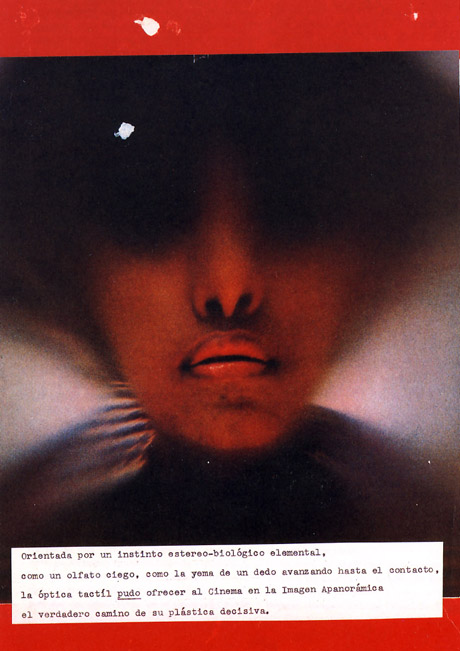

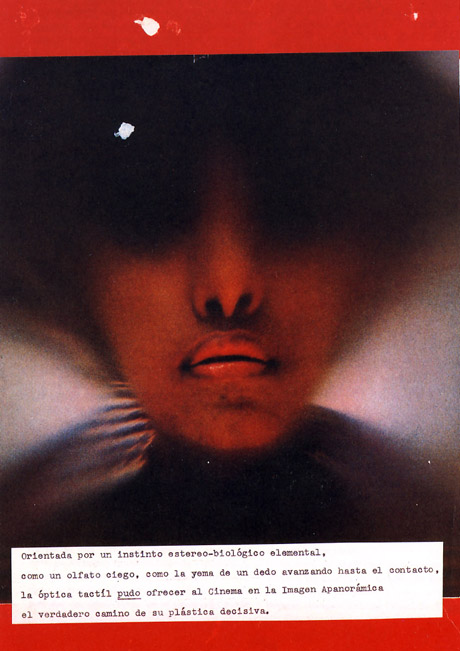

Val del Omar spent much of his time exploring technology related to the innovations in film in his time (sound film, color, wide screen and so on), as well as other fields including electro-acoustics, radio, television and the educational applications of audiovisual media. Some of his inventions sought to offer practical solutions, especially in the threadbare economy of Franco’s Spain, which depended largely on imported technology, film stock and other resources. Others explored the idea of the comprehensive artwork with a rare and visionary instinct—all the more so when we consider that he made many of these ideas public between 1928 and 1944. They include Screen Overflow and the quest for acoustic and visual cubism using enveloping diaphonic sound and tactile vision, with its blinking, pulsating light. Moreover, Val del Omar stayed up to date on the latest media and technology and even glimpsed the possibilities offered by cybernetics, laser, digital video and mixed media.' -- Museo Reina Sofía

JOSE VAL DEL OMAR COLLECTION

José Val del Omar was born in Granada on October 27th, 1904. From early childhood he amused himself by projecting images magic-lantern fashion, and after a stay in Paris in 1921 he discovered his vocation in the cinema.

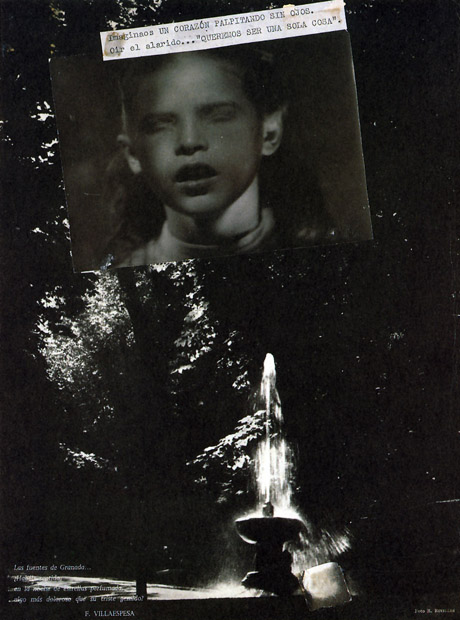

In 1928 he used the specialized press to publicise his astonishingly precocious ideas for a variable-angle lens, for concave screens and for achieving relief effects by means of lighting, effectively prefiguring some of the most significant lines of his later researches and discoveries. Between 1953 and 1955 he made the film Aguaespejo granadino [Water-mirror of Granada], “a short audio-visual essay in lyrical art”, conceived in part as a showcase for his technical innovations.

Its screening at the Berlin Film Festival in 1956 and the International Experimental Film Competition in Brussels during Expo 1958 caused a considerable stir and generated a warm response and enthusiastic reviews.

He went on to make Fuego en Castilla [Fire in Castile], whose lengthy gestation extended from 1956 to 1959, in which he introduced the fundamentals of his TactileVision or pulsatory tactile lighting. The power of his images and his electro-acoustic soundtrack earned him a number of awards at film festivals: Cannes 1961 (the year that Buñuel received the Palme d’Or for Viridiana), Bilbao 1961 and Melbourne 1962.

With an extraordinary artistic and technological talent, Val del Omar was a “believer in cinema” inspired by new horizons but interrupted by the Civil War. In 1928 he anticipated various of his most characteristic techniques, including the “apanoramic overflow of the image” beyond the limits of the screen, and the concept of “tactile vision”.

DOCUMENTARIES :

Scenes 1932

Christian Feasts / Secular Feasts (1934-35)

Vibration of Granada (1935)

Home Movie (1935-1938)

Scenes 1932

Christian Feasts / Secular Feasts (1934-35)

Vibration of Granada (1935)

Home Movie (1935-1938)

ELEMENTARY TRIPTYCH OF SPAIN : Restored in HD

Galician Caress (Of Clay) (1961, 1981-82, 1995)

Fire in Castile (1958-1960)

Water-mirror of Granada (1953-1955)

Galician Caress (Of Clay) (1961, 1981-82, 1995)

Fire in Castile (1958-1960)

Water-mirror of Granada (1953-1955)

VALDELOMARIAN FILMS :

Cristina Esteban: Ojala Val del Omar (1994)

Antonella La Sala: Vertex Vortex (2002)

Javier Viver: Val del Omar Laboratory (2009-2010)

Cristina Esteban: Ojala Val del Omar (1994)

Antonella La Sala: Vertex Vortex (2002)

Javier Viver: Val del Omar Laboratory (2009-2010)

Other Documentaries About The Author Available In HD & SD :

DOWNLOADS :

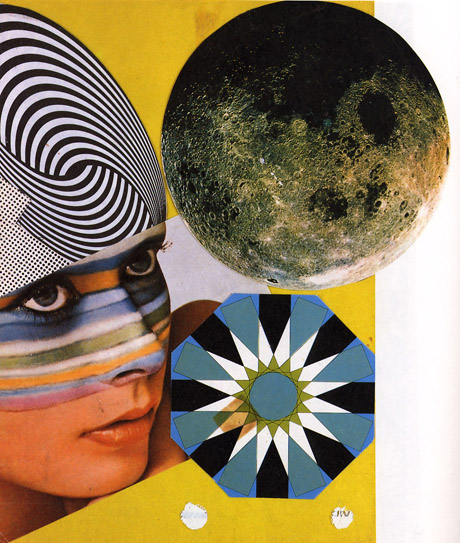

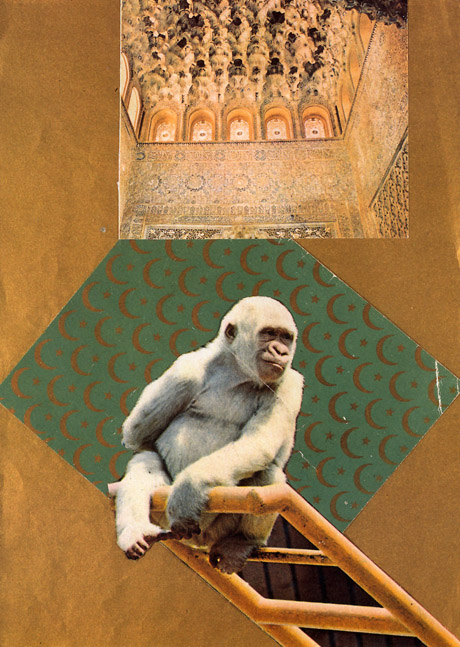

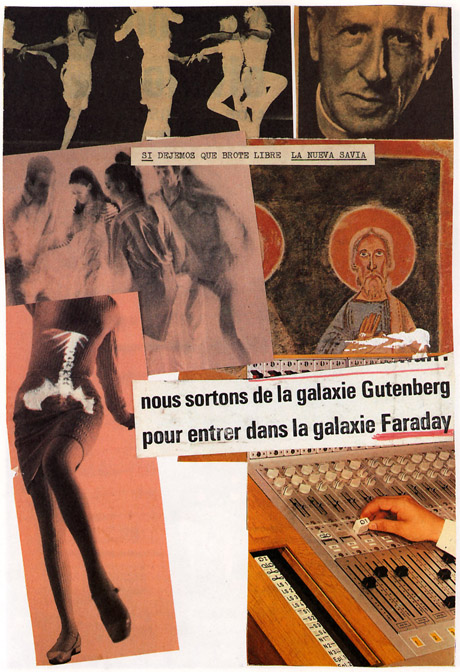

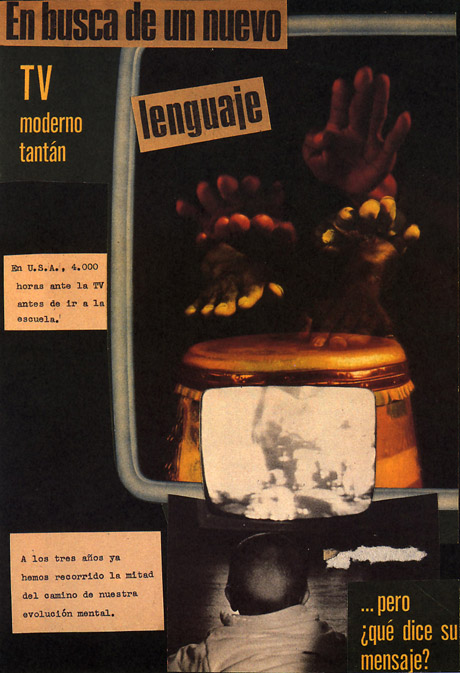

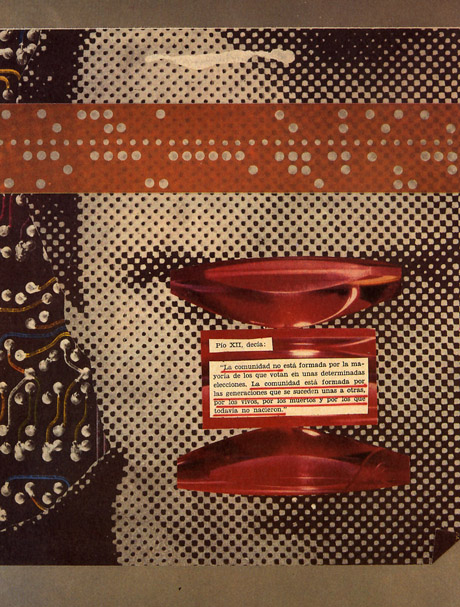

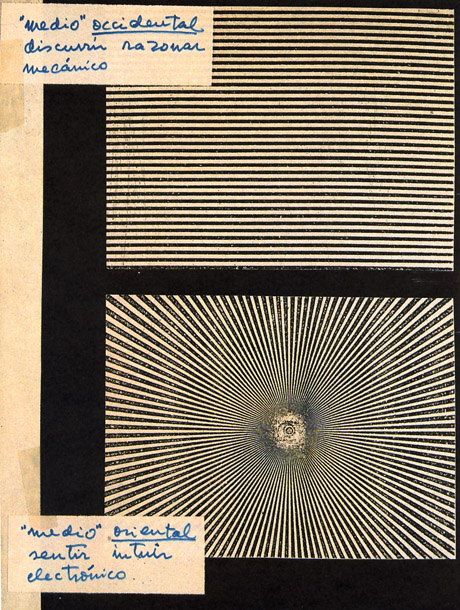

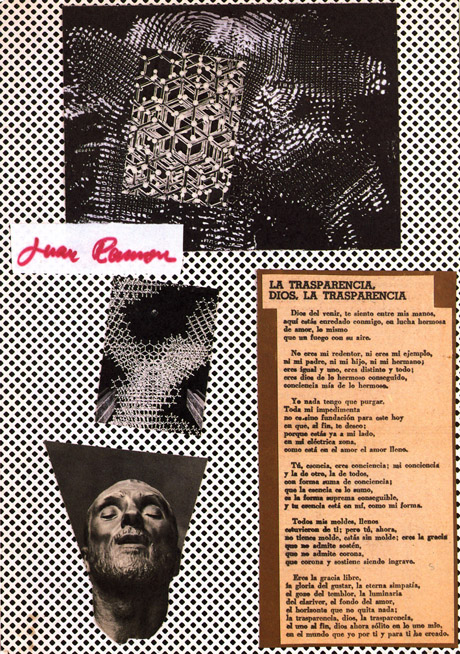

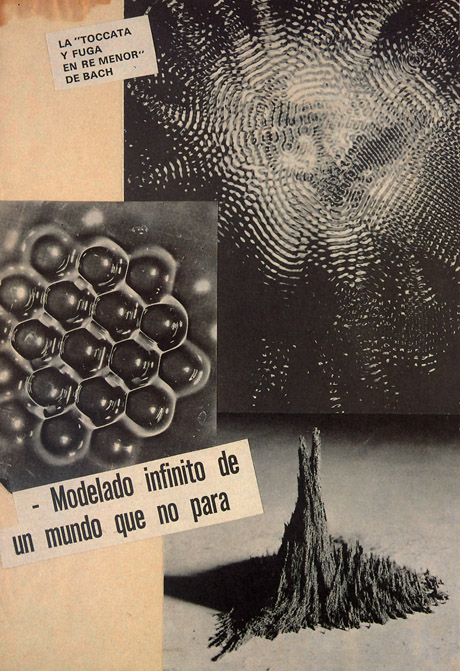

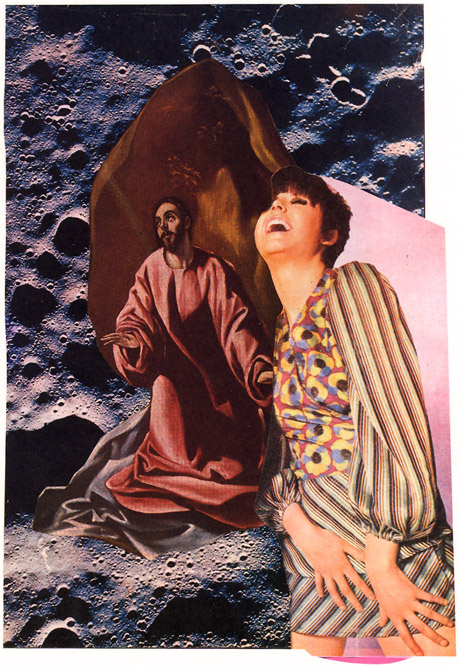

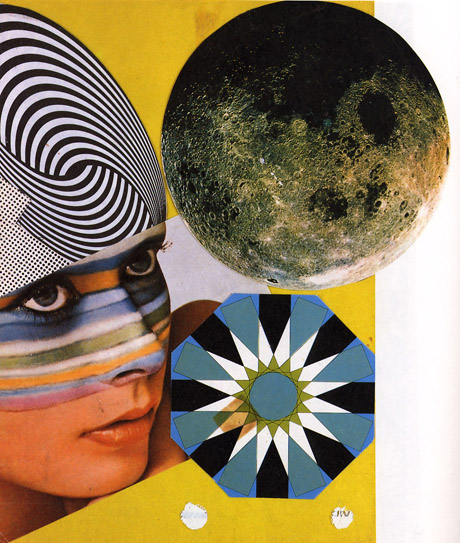

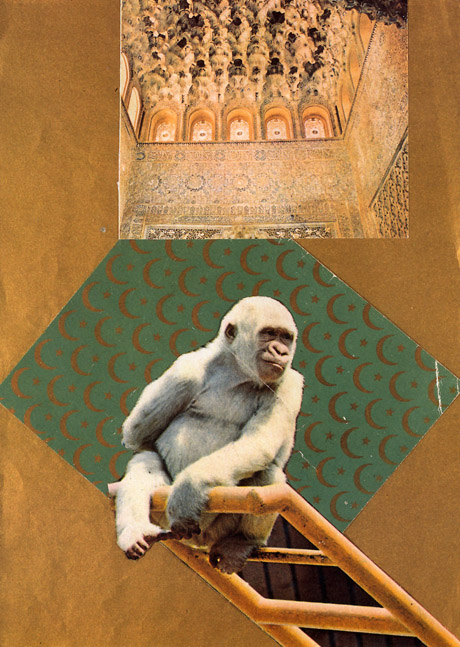

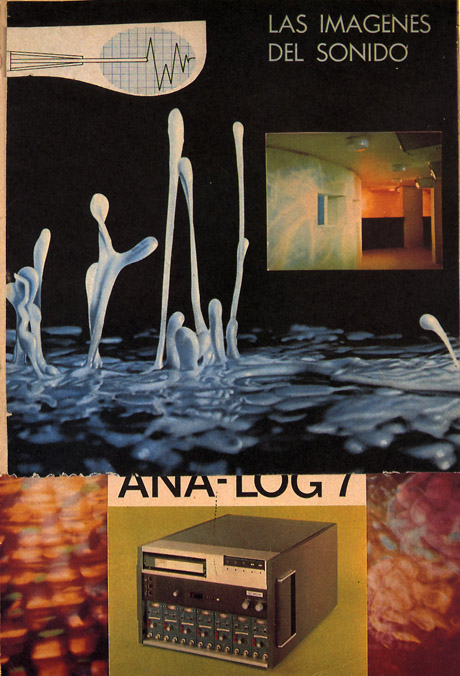

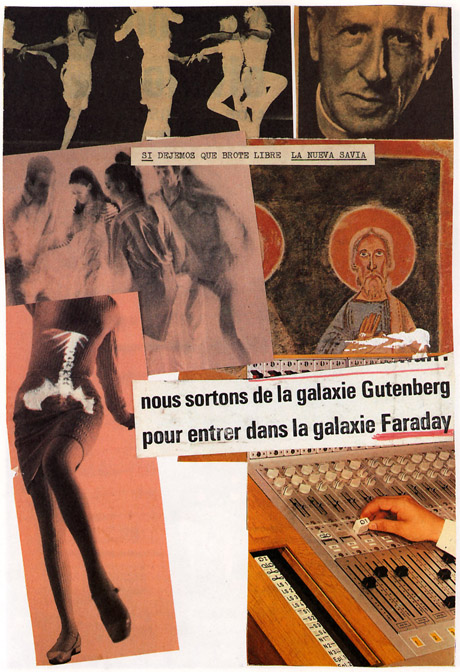

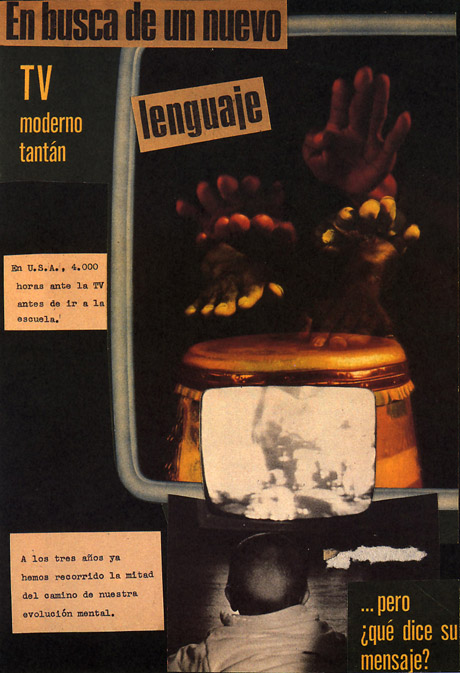

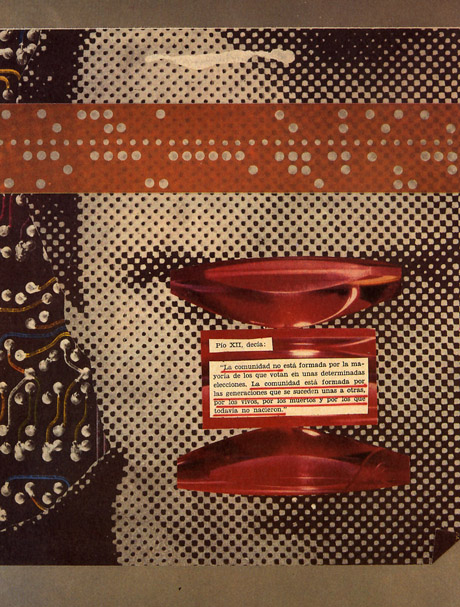

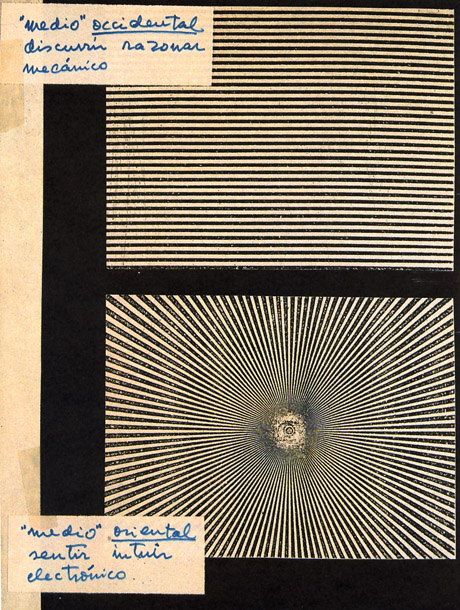

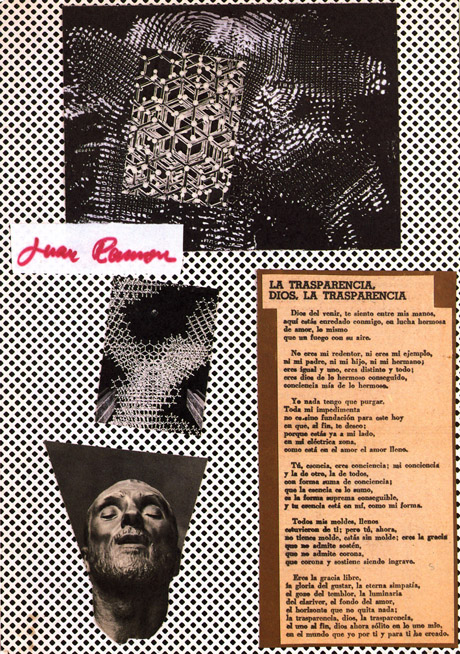

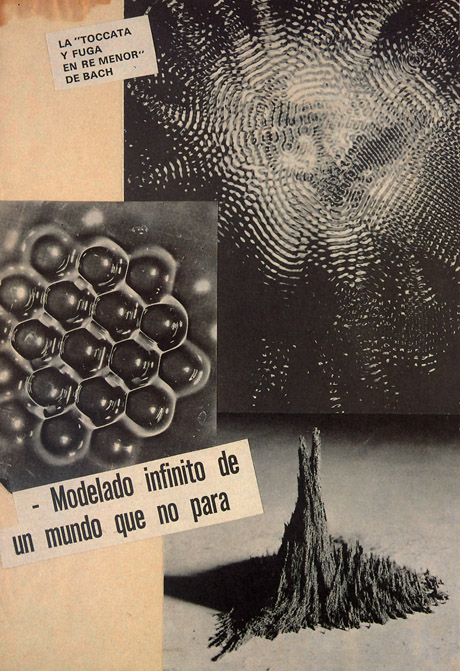

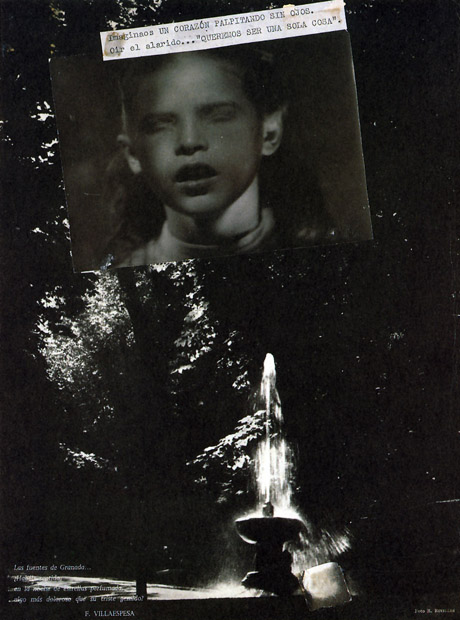

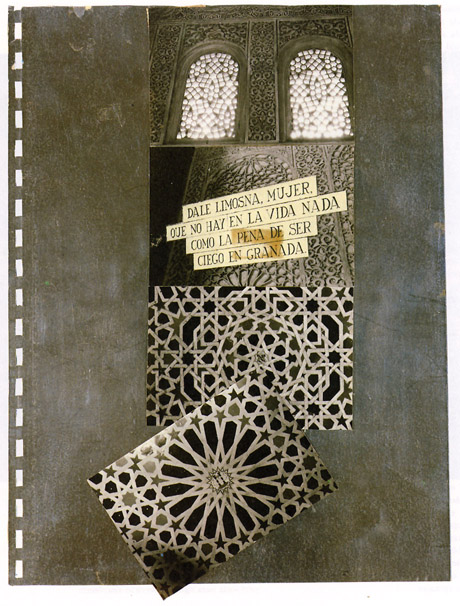

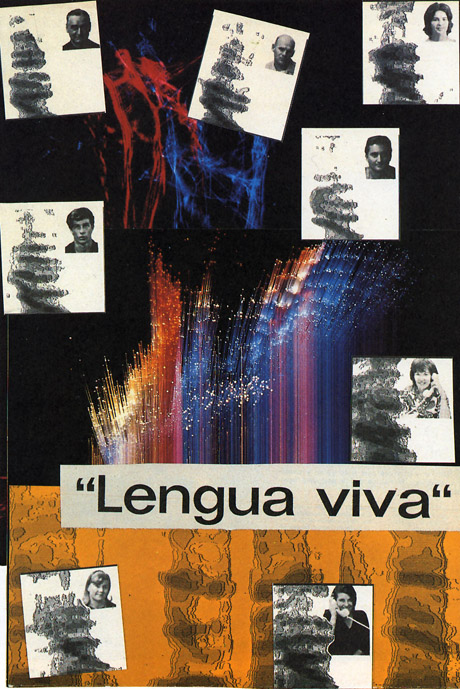

![Surrealist Collage- José Val del Omar

electronicalrattlebag:

billyjane:

José Val del Omar (Granada 1904 - Madrid 1982) With an extraordinary artistic and technological talent, Val del Omar was a ”believer in cinema” inspired by new horizons that he formulated in the term PLAT – representing the totalizing concept of a ”Picto-Luminic-Audio-Tactile” art – apart from being a contemporary and a comrade of Lorca, Cernuda, Renau, Zambrano and other figures of a Silver Age of the Spanish culture, interrupted by the Civil War.

more@valdelomar

[akubi,thanks for the hint, i forgot about this master of surrealist collage]](http://25.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_kpb2updgxC1qztk1wo1_500.jpg)

DVD: José Val del Omar’s Tríptico Elemental and Other Experiments from Spain

By Matt Losada

For most cinephiles the mention of Spanish experimental film conjures an abyss, from which the only images to readily appear are of Buñuel’s (Paris-made) Un chien andalou (1927) and L’Age d’or (1930), and the rural documentary Las Hurdes (1933). It is often said that Buñuel had to leave Spain to make avant-garde art, and even counting those contemporary filmmakers like José Luis Guerín or Albert Serra, it is still a meagre panorama compared to that of other European countries. But this dearth is due less to a lack of works than to their very limited distribution. In both Latin America and Spain experimental film is a relatively expansive concept, although one that keeps a low profile. This is often due to politics, either those of the filmmakers or of whoever is in charge at a national level. With a few very notable exceptions—like Santiago Álvarez in Cuba—neither right nor left has historically been especially relaxed about people messing about with motion-picture cameras and showing the results at informal gatherings. So the underground has mostly stayed underground, even more so than in North America and Europe.

All over the Spanish-speaking world however, much experimental film has been made, generating on both sides of the Atlantic a surrealist-inflected historical avant-garde, ‘60s formal innovation in the interest of political militancy, a Super 8 underground of the ‘70s, and the contemporary proliferation of work enabled by video technologies. Several DVD collections of experimental film have recently been released by the Barcelona-based Cameo Media, a distributor that specializes in independent and experimental film. Unquestionably the most invaluable of these, the five-disc Val del Omar: Elemental de España, is dedicated to the works of the unique solitary inventor-artist José Val del Omar, the most notable of which is the formidable Tríptico elemental de España (Elementary Triptych of Spain, shot between 1953 and the mid-‘60s), without a doubt the most ambitious project in Spanish cinema history and one referred to by Amos Vogel in Film as a Subversive Art as “an explosive, cruel work of the deepest passion…nameless terror and anxiety…one of the great unknown works of world cinema.”

The Tríptico is a series of three “elementales,” (the name would translate as “elementary”), which Val del Omar proposed as a cinematic genre distinct from the documentary: Aguaespejo granadino (Water-Mirror of Granada, 1955) Fuego en Castilla (Fire in Castile, 1960), and Acariño galáico (Galician Caress, begun in 1961 and completed posthumously in 1995 from Val del Omar’s footage, recordings, and notes). Parts of the Tríptico won awards at the Cannes, Bilbao, and Melbourne film festivals in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s before disappearing from view for decades, noticed only by such diligent UFO-spotters as Vogel. Since the 1980s the films have occasionally been screened theatrically, most notably opening a 1982 retrospective of Spanish experimental film at the Centre Pompidou and inaugurating the Filmoteca de Andalucía in 1989, which has since recovered and restored several of Val del Omar’s earlier documentaries.

Val del Omar’s cultural formation took place in the intellectual ferment of the Granada-based avant-garde of the ‘20s. He was a neighbour of the composer Manuel de Falla and a friend of Federico García Lorca, both central figures of Spain’s modernist cultural flowering. During the years of the Spanish Republic, he worked with themisiones pedagógicas (teaching missions), a state-run program that brought modern culture and learning to rural populations still dominated by large landowners and the Church, challenging the latter’s monopoly on truth. The misiones’ project included the use of cinema as a pedagogical instrument, but Val del Omar—a utopian modernist with a pronounced spiritual bent—saw the relatively young medium as a way to foster a collective identity among its viewers, overcoming the principle of individuation that both confined human beings to a brief and tragic temporal existence and hindered social progress.

Val del Omar filmed more than 40 silent documentaries and took hundreds of still photos, many of which show peasant faces entranced by the novelty of the cinema. This power of the medium later motivated many of Val del Omar’s inventions and the dream of the grand project he called meca-mística (mechanical mysticism), in which the cinema would serve as a “magic instrument, amplifier of our vision,” making palpable—thanks to its indexicality, the traces of the material brought to the screen by light—what he called the “mystery” or “substance”: that immutable, impalpable omnipresence of elementary matter that makes up the cyclical rhythms of the universe, and that has been displaced by temporal, especially modern, concerns.

However, instead of a programmatic rejection of the modern à la the Spanish right, Val del Omar spent much of his life developing a cinematic technology that would facilitate ecstatic transport beyond the limitations of the body’s sensorium. Herein lies the paradox: a humanist—called by fellow restless filmmaker Luis García Berlanga “one of the last survivors of that proud caste of the enlightened that has done so much to dignify scientific and humanistic progress in Spain”—who strove to advance progress not through reason but through a mystic idealism. Val del Omar’s notion of progress is not an advance from the ideal to the material, nor from faith to reason, but is instead an inspired combination of the old plaint of the fall into temporality and the modernist conception of bourgeois individualism as a post-lapsarian condition. Val del Omar’s mysticism addresses both, by seeking to unite man with the divine in nature and with the rest of humanity through the cinema.

After the Civil War, Val del Omar’s dreaming found little room in the autarchic Spanish cultural field of the ‘40s and ’50s. Congenitally suspicious of cultural marginality, the Franco regime fomented a monocultural commercial cinema as a natural outgrowth of its militaristic National-Catholic project, vesting all authority in the major national studios and leaving little space for avant-garde experimentation. Unable to film independently, Val del Omar turned to technological experimentation with lenses, sound, and lighting and projection technology as a part of his mystical project, designed to thrust the Tríptico’s viewer into ecstatic transport by eliminating the distance between spectator and spectacle.

While working in special effects at the Estudios Chamartín (one of the four major film studios at the time) and on radio programs during the early ‘40s, Val del Omar filed several patents for inventions in audio technology, one of which, the Diáfono sound system, was his first technological step toward the total spectacle of the Tríptico, placing sources both in front of and behind the spectator, each on a separate track, to produce what he called a “dialectical dialogue” of sound. Diaphony was not meant to enhance sonic verisimilitude like the stereophony it predated, but to enhance the power of the cinematic apparatus beyond the mere faithful representation of reality. By 1956, when Aguaespejo granadino played at the Berlinale, Val del Omar had also perfected what he called Desbordamiento Apanorámico de la Imagen (Apanoramic Overflow of the Image), in which a simultaneous projection of abstract images, synchronized with the rhythms of the film’s sound, could be seen on the front and side walls and the ceiling of the theatre, creating in effect a concave screen that engulfed the spectator. He then developed Visión Táctil (Tactile Vision), a system of pulsating light intended to “tactilize” visual perception, which he used for the second part of theTríptico, Fuego en Castilla. These inventions were designed to release his films from confinement within the edges of the flat screen, a move from the optic toward the haptic and an expansion of perceptive possibilities beyond those normally available to the sensorium, both in the cinema and outside. In the Tríptico, the elemental movement of water, clouds, and light in rhythms normally invisible to the naked eye is made perceptible through Val del Omar’s many inventions, in combination with freeze frames, fast and slow motion, filters, and anamorphic mirrors. The resulting experiences range from solemn to ecstatic, from torment to illumination.

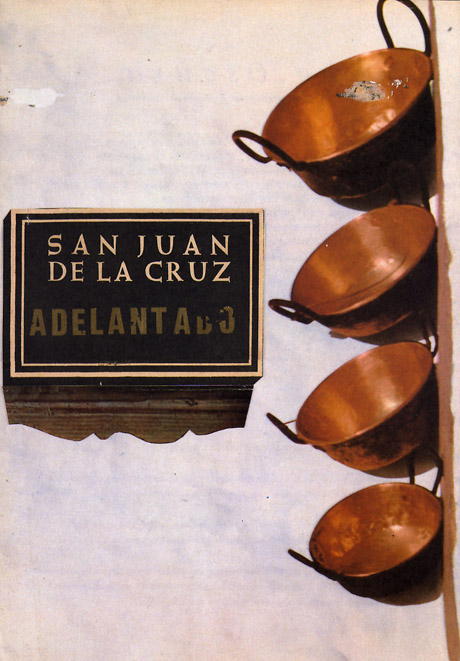

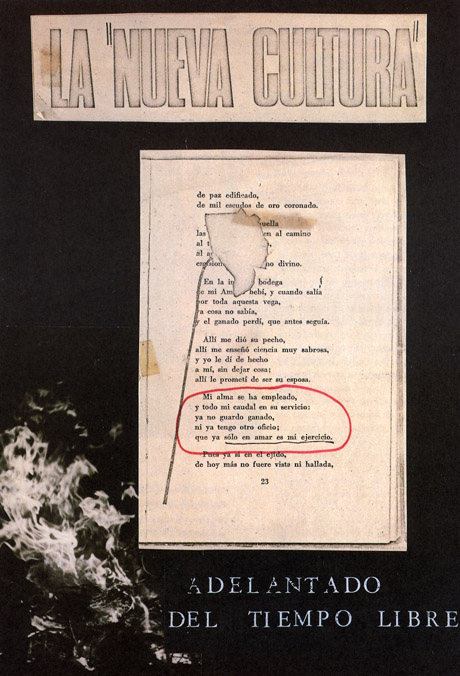

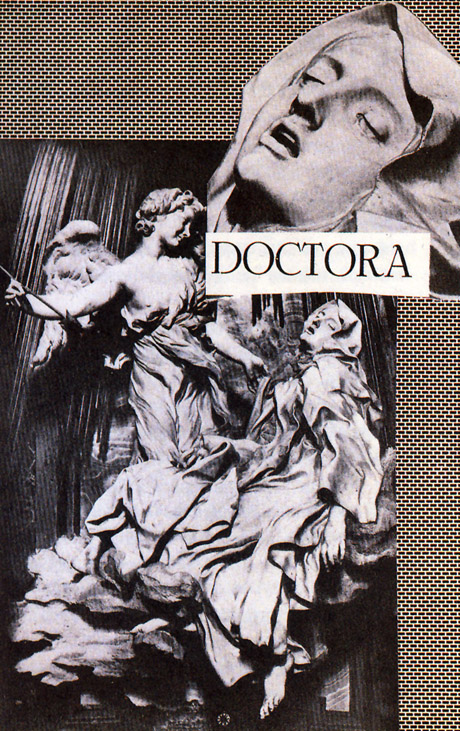

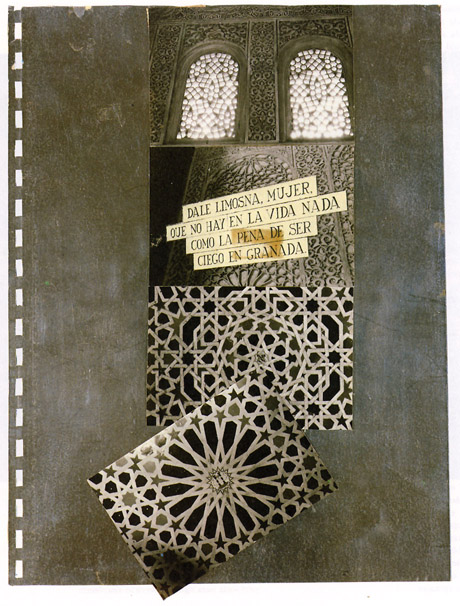

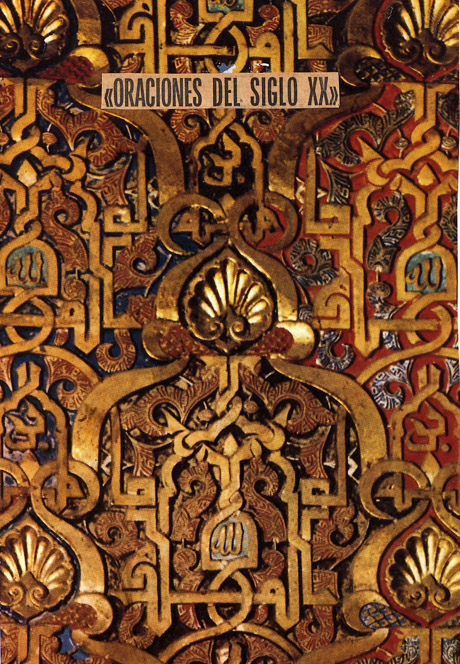

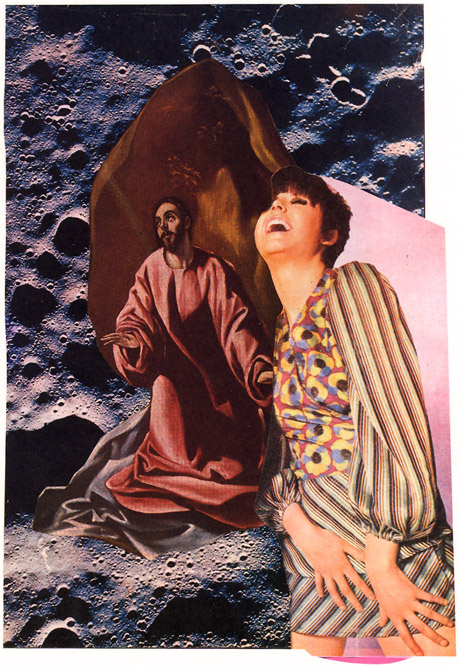

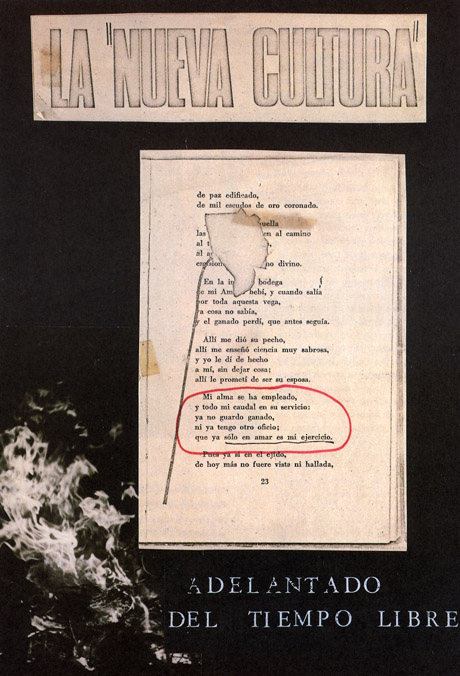

The settings of the Tríptico—Galicia, Castile, Granada—trace an arc across the Iberian Peninsula, while the corresponding elements of earth, fire, and water point to a pre-modern epistemology, restoring the Islamic and Jewish others long suppressed by those traditionalists (now restored to power by the Nationalist regime) who promulgated nostalgic imaginings of a homogeneous Catholic national origin. Drawing freely on the writings of the 16th-century mystic San Juan de la Cruz—whose poems and commentaries describe a spiritual journey from a fallen temporal condition, advancing, cycling back, and eventually progressing through “purgation” to the “illuminative” stage—Val del Omar sought to reconcile this older mysticism with the avant-garde project of shocking the spectator out of an anaesthetized modern condition, in the process implicitly scorning the Franco regime’s militaristic mediocrity. Following the sequence of San Juan’s interior journey, the Tríptico was designed to be viewed in the reverse order of its making: from the post-lapsarian state of Acariño galáico, in which the spirit is trapped by the body’s attachment to the material, through the sufferings of the “dark night” of purgation’s painful release from the emotional attachment to the material (Fuego en Castilla), and closing with Aguaespejo granadino’s mystical union with the divine in nature.

The central sequence of Fuego en Castilla—and thus of the whole Tríptico—is the most violently powerful, while the moments of mystical union in that film andAguaespejo granadino are sensorial triggers of ecstatic transport. The former is an abstract yet very material representation of the sufferings of purgation, consisting of faces and bodies of religious statues in movement through a non-space of unreadable perspectives. Pulsating bands of light and shadow—Tactile Vision—crawl across their features in a sort of radar-made-visible. Unidentifiable but violent sounds—the crackling of fire, the cracking of whips, the crunching of bones?—assault the viewer from all sides, raking the coals of a collective religious memory that features centuries of saints’ lives, inquisitions and fanaticism. The intensity of this purgation is followed by the peace and relief of mystical union, a mise en scène of San Juan’s citation of the Song of Songs—“Winter is now past, the rain is gone, and flowers have appeared in our land”—as sensorial acuity is heightened through the defamiliarization brought by subtle distortions to sound and colour in the final sequence of this otherwise black-and-white film.

Although Val del Omar might have considered the digital format itself to be post-lapsarian, due to its breaking of the links of light, and thus indexicality, upon which he theorized his cine-mysticism, the exceptionally well-transferred digital simulacra of theVal del Omar, elemental de España set are the only access to the works most viewers will have. More difficult to rebut is Val del Omar’s resistance to non-theatrical viewing of the Tríptico, since the immersive technological apparatus and the mass viewing he imagined is unlikely to be reproduced in the home. But at least the Tríptico appears with impeccably crisp imagery, and in two versions, one with the Diaphonic sound and the other in a traditional audio setup. The films lack the Desbordamiento Apanorámico, but the Visión Táctil is seen in many of the images of Fuego en Castilla.

The Tríptico is accompanied by several documentaries Val del Omar filmed in rural Spain in the ‘30s—Estampas 1932 (Scenes 1932), Fiestas Cristianas/Fiestas Profanas (Christian Feasts/Secular Feasts, 1934-35), Vibración de Granada(Vibration of Granada, 1935)—along with home-movie footage, a gallery of photographs taken on the misiones, and a selection of films inspired by Val del Omar. The most interesting of these are the invaluable Laboratorio Val del Omar (Val del Omar Laboratory), a 2010 video made by Javier Viver that documents Val del Omar’s technological innovations with extensive footage filmed in his still-existing workshop, and Tira tu reloj al agua (Throw Your Watch to the Water, 2004), Eugeni Bonet’s experimental feature that employs Val del Omar’s wonderful late colour footage in a meditation on time and the Andalusian landscape. The beautifully designed, if unwieldy, fold-out package comes with a very informative 44-page booklet in Spanish and English, and the films have English subtitles, although these are inadequate in the case of voiceover commentary of Laboratorio Val del Omar.

The two other collections from Cameo—derived from the recent work by the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona to restore and screen experimental works, which also produced the travelling program “From Ecstasy to Rapture: 50 Years of the Other Spanish Cinema”—survey the experimental cinema of the Spanish-speaking world, one for each side of the Atlantic. The two-disc Del extasis al arrebato surveys 31 Spanish works from the late ‘50s to the present, while Cine a contracorriente’s single disc presents 19 Latin American film and video works made between 1933 and 2008. Not present are the elsewhere-available feature-length works of Pere Portabella, Adolfo Arrieta, Guerín, Pino Solanas and many others, but both sets offer an excellent, if necessarily partial, sampling of otherwise unavailable works.

Del éxtasis al arrebato—which includes the middle section of Val del Omar’s triptych,Fuego en Castilla—features several films made during the transition to democracy, when Spanish culture began to return from decades of internal exile. Iván Zulueta is known as the “maudit auteur” of this period. With the 33-minute A MAL GAM A (1976), he brought the lyrical film into the territory of mystico-psychedelia. The cinema as drug/vehicle for rapture is the pretext of what is also a documentary of an agoraphobic mode of artistic production, protagonized by the filmmaker himself (the trans-linguistic homophone “Jim Self” appears in the credits) and shot mostly in the family villa in San Sebastián. The combined effects of the looping psychedelic noise-track, vertiginous zooms, and an associative montage that often oscillates between the scatological and the sacred—toilets and flowing silly putty are juxtaposed with decayed religious iconography—make this the closest Zulueta ever came to creating a filmic vehicle of rapture.

Eugènia Balcells’ nine-minute Boy Meets Girl (1978) is a kind of situationist slot machine. The screen is divided down the middle, and found pop-culture images of women, on the left, and men, on the right, roll up and down as if on the edge of a wheel; when they stop, the random couplings of mediatized archetypes that result may invite certain viewers to ruminate on Debord and détournement. Three shorts by another Barcelonan artist, Juan Bufill—a minimalist in the most cinematically robust sense of the word—displays his Cezanne-like aesthetic concern for random variations between pure light and form, movement and stillness, locating him as a precursor to contemporary filmmakers like Guerín. His Green, Paraíso, (both 1978) and Arena(1979) are three-minute silent Super 8 pieces that explore the most minimal changes of texture, light and movement across both handheld shots and fixed-camera tableaux. José Antonio Sistiaga, another notable artist whose work is unavailable elsewhere, is represented by a short final fragment of his seven-minute Impresiones en la alta atmósfera (Impressions in the Upper Atmosphere, 1988-89), which was intended to be projected upwards on a dome. Sistiaga painted directly on 70mm film a circular (planetary?) form, around which dance shifting colours in a psychedelic acceleration matched by the soundtrack’s deep-space roar and howl.

Brutal Ardour (1979) is a highlight of the set. Manuel Huerga slowed down, by refilming on Super 8, a few shots of a pastoral, sepia-toned scene inhabited by a rather pre-Raphaelite couple, backed by Brian Eno’s elongated version of Pachelbel’sCanon. At times Huerga lets the individual photograms linger, at others he selects details as the frames click by. The film grain becomes as much a protagonist as the couple, and the marvel of the slow lingering on details of an already pleasurable scene prompts the perceptive apparatus to leisurely unfold, producing 29 minutes of pure aesthetic pleasure for a viewer receptive to its pace and appreciative of the materiality of film.

The set is rounded out by several Norman McLaren-inspired hand-painted or scratched films, a few derivative (of Godard…of Warhol…) late-‘60s shorts typical of much of what was being done in Barcelona at the time, and a less-inspired selection of more contemporary works. The beautifully packaged set includes useful subtitled interviews in which many of the filmmakers discuss the works at hand, and a very informative 157-page booklet in Spanish and English.

The Latin American-focused Cine a contracorriente opens with two surrealist-inspired trance films made by artists best known for their work in other media. The Argentine modernist urban photographer Horacio Coppola made the 138-second Traum (Sueñoor Dream) with Walter Auerbach while the two were studying at Bauhaus in the early ‘30s. A proliferation of unexpected camera angles fragments the classical analytical editing of its dream-logic narrative. Like the next film—Esta pared no es medianera(This Wall Is Not a Party Wall), made by the Peruvian modernist painter Fernando de Szyszlo in 1952—its somewhat formulaic Freudianism locates it squarely in the historical avant-garde. (Unlike the rest of the films on the disc, the latter’s image quality leaves much to be desired since, once thought lost, it had to be sourced from an unfortunate Betamax copy.) Ferruccio Musitelli’s La ciudad en la playa (The City on the Beach, 1961) foregoes narration to instead observe “normal” people doing “nothing” in a day in the life of Montevideo’s Playa Pocitos. The playful result abounds in spontaneous beauty and a Tatiesque humor.

With the Bolivian Jorge Sanjinés’ Revolución (1963) the collection moves on to the political avant-garde of the ‘60s. Sanjinés is a key filmmaker, whose career trajectory was basically a continuous experiment around film form, political awakening, and an indigenous audience. His Eisenstein-influenced Revolución is an early phase of the experiment, opening with documentary testimony of the poverty endured by the indigenous community in La Paz, but soon turning into an exhortation to political action. Another giant of Latin American political cinema, Santiago Álvarez, worked in revolutionary Cuba in a unique example of state-sponsored experimentalism. His classic 1965 denunciation of US institutional racism, Now!, is a montage of found photos and footage of repressive state violence inflicted on the African-American population, backed by Lena Horne’s powerful rendition of the title song. Álvarez lets the music dictate the rhythm of the montage, generating strong affect to power the otherwise straightforward denunciation.

At 29 minutes, Agarrando pueblo (1978) is the longest film on the disc, and well worth the megabytes. Made by the prolific Colombian documentarists Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo, the self-reflexive parody critiques the emptying of the Rouchian interactive documentary of its ethical dimension in the production of “porno-miseria,” documentaries for European or North American consumption of sensationalized third-world poverty. The premise is the filming of a vérité documentary on the streets of Cali for German television, and the film constructs two gazes: one, in colour, is that of the porno-miseria documentary; the other, in black and white, a hilarious “making-of” in which the cynical filmmakers are seen at work, provoking the impoverished to perform self-abasement in exchange for cash. Ospina and Mayolo edit the two gazes together in temporal continuity, periodically liberating the viewer from the address of the documentary through the demystifying behind-the-scenes gaze.

The disc provides what will no doubt be most viewers’ first glimpse of the Argentine Super 8 underground that flowered in the ‘70s, with one film each by its two key figures. Amazona (1979-1983), by Narcisa Hirsch, is a very open visual text that activates the Amazon myth—female warriors who cut off their right breast to better wield a bow and arrow—without allowing it to monopolize the film’s meaning. Resonances between disparate images of landscapes, a rowboat on a lake, and a woman, along with changes in focus and not-quite-there visual rhymes, produce expansive poetic suggestion. Claudio Caldini’s four-minute ocular massage Ofrenda(Offering, 1978) is a rush of single-photogram images of daisies in a gradually fading light, its mood reinforced by Alice Coltrane’s hypnotic harp.

Of the more recent works, the highlights follow: Ilha das flores (Isle of Flowers, 1989, Jorge Furtado) parodies the scientific documentary, underlining the absurd logic of capitalism and the abuse of the word “freedom” as it traces a tomato’s trajectory from cultivation through rejection, banishment to a landfill, rejection again as pigswill, to its destiny in the hungry mouths of dispossessed—but “free”—Brazilians. Corazón sangrante (Bleeding Heart), a 1993 music video by Ximena Cuevas, takes on the Mexican cultural icon of the masochistic female through a hyper-kitsch aesthetic of digi-morphing visual matches and other heavy-handed early-digital manipulations. InOpus, a five-minute video made in 2005, José Ángel Toirac distills a speech by Fidel Castro, extracting only the frequent mentions of numbers, which are heard against a solid black screen on which the corresponding numerals appear in white text. Castro’s discourse disappears, the very personal grain of his voice rises up, and mental flight ensues. In his 2008 Ojo de pez (Fish Eye)—a video of subtle sensations in an age when the body’s contact with the real is ever more mediated by the digital—Gabriel Vargas uses off-screen sound to thread a tenuous narrative through a series of rural images on high-definition video. The imagery is thus freed to explore in close-up a fascination with details that activate, virtually, the rest of the corporeal sensorium: the rich smell of fresh milk, the worrying prick of a bee’s feet on a nervous eyeball, a knife slicing through a live fish’s scales and the blood that is released. Cine a contracorriente’s single disc is more bare-bones than the others—a simple plastic box, no filmmaker interviews, a shorter booklet (32 pages, in Spanish and English)—but the films are subtitled in English and the excellent selection makes it well worthwhile.

Projection as a Magnetic Field: The Overflowing of Val Del Omar

Projection as a Magnetic Field: The Overflowing of Val Del Omar

Esperanza Collado

1. Cinemist

José Val del Omar is one of the greatest visionary personalities of the 20th century, an eccentric creator maudit within the heart of Spanish cinematography. As a believer in the cinema and a 'cinemist' (a term derived from ‘alchemist' he often used to define his unclassifiable occupation), Val del Omar had a clearly defined transcendental mission: to combine "the horizontal frenzied gears of the machine" with the "vertical, mystic tradition"* of Spanish culture.

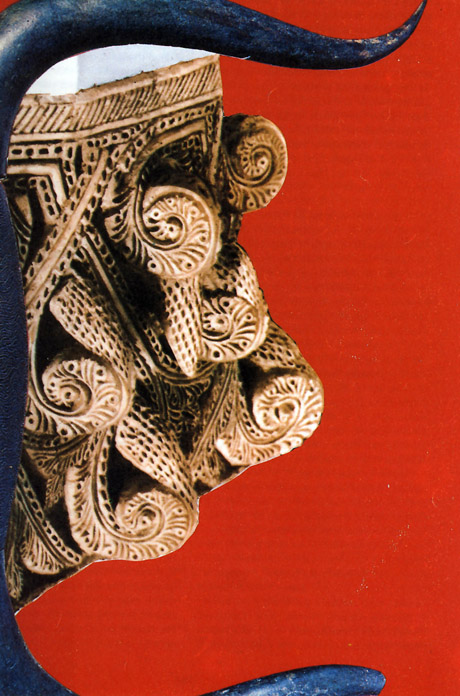

All stills from Tríptico Elemental de España

He envisioned a different kind of cinema, one of visual poetry driven by what he called ‘meca-mística', a mechanical mystic belief based on the philosophical idea of a technology, of which cinema is the revealing instrument, capable of transmitting emotion into our culture. Val del Omar wanted to make visible the invisible in order to awake, provoke a reaction in and penetrate the senses of "passive audiences that live in a world of machines that stain our brains". And, in order to achieve his mission, he expanded his films or 'cinegraphs' with inventive devices of his own making. As a tenacious researcher, Val del Omar combined the sensibility of a poet and the technical knowledge of an engineer to develop a cinema of aesthetic preoccupations in which the centrifugal, mystic machine overflows both the confines of a medium and the architectures of perception.

Val del Omar was born in 1904 in Granada. His works and writings emphasise this fact as absolutely vital. Even though he lived in other cities, he always felt a special connection with Granada. The Andalusian city had experienced historical periods of artistic and scientific splendor, especially during the Middle Ages whilst under the reign of Al-Andalus, when the Alhambra palace was built. But it had also known dark periods dominated by strong political and religious conservatism. Living through the Civil War, when the Nationalists took over the city and killed thousands of Granadans, Val del Omar lost his friend Federico García Lorca, but not his convictions. A decade before, inflamed by the French avant-garde he discovered in Paris, he also realized that cinema could be transformed into a supreme art of experience.

In the late 1920s, Val del Omar began to publish enthusiastic accounts of ideas and projects in specialized journals. His subjects ranged from the invention of a camera lens of variable angle capable of capturing time, later known as a ‘zoom lens', to concave screens and other remarkable systems that could present sounds and images in relief as well as light in motion. He tried to patent these and other inventions, but his continuous efforts to find substantial recognition and financial support, even internationally, were ineffectual. He applied his techniques to his own film experiments, though, including the monumental Tríptico Elemental de España. But he was condemned to remain an insular genius. In fact, his work, probably too far ahead of its time and context, wasn't adequately acknowledged until near the end of his life. Val del Omar died in a car accident in 1982 when he was working on a prelude to his Tríptico entitled Ojalá, and Eugeni Bonet was preparing a screening series of Spanish avant-garde cinema that included his films for the Centre Pompidou.

2. Overflows and Expansions

Val del Omar believed projection must be a liturgical act, and considered his 'commotional spectacle', his synthesis of spectacle and mysticism, an overflowing cinema with a vertical direction. His three main inventions prefigure the adventure of chasing the ghost from the machine to superimpose it upon another labyrinth, an open, infinite maze that finds its reflection in the 'sinfin' ('without end') title with which his films usually ended.

Between the spiritual and the technological, his visionary spectacle included the Sistema Diafónico (‘diaphonic system'), an electro-acoustic sound system created in 1944 as a critical response to the stereophonic method common in Hollywood movies. Sistema Diafónico was based on sonic polarization rather than on the opposition of the ears, and it was first used in Val del Omar's Aguaespejo Granadino (1953-55), the first part of his triptych. ‘Desbordamiento Apanorámico de la Imagen' (‘a-panoramic overflowing of the image'), an experiment finished in 1957, consists of penetrating the peripheral vision through non-figurative inductor images arranged on the walls, floor and ceilings while a concentric figurative film is screened. ‘Desbordamiento' was first tested publicly during a show of Aguaespejo Granadino in Berlin. His third major experiment, Tactilvisión or Tactilevision (1956-59), is a method aimed at bringing cinema to the body through approaching the senses in a direct way by using a complex series of devices based on the vibration of light. Some of his ‘tactile' experiments were applied to the second part ofTríptico Elemental de España, Fuego en Castilla (1956-59), which he described as a "somnambulist essay of tactile vision".

Since 2010, these and other inventions have been on public display for the first time in thirty years. This is thanks to a touring exhibition, Desbordamiento de Val del Omar(‘Overflowing of Val del Omar'), doing the rounds of some of Spain's more prominent art galleries. It consists of a comprehensive selection of his works that provides a rich understanding of the multiple facets of the artist. Additionally, after such longstanding neglect, the exhibitions have led to the publication of some substantial volumes on Val del Omar, including his own writings, research notes, and poetry.

The show, curated by Eugeni Bonet, encompasses Val del Omar's films, writings, collages, drawings and all sorts of documentation and artefacts relating to his explorations in the fields of cinema, television, radio and electro-acoustics, as well as to Las Misiones Pedagógicas. The latter was a collective endeavour, a travelling educational project developed during the republican years before the Civil War to bring art and culture to remote areas of rural Spain. Val del Omar participated in it, and Las Misiones Pedagógicasnow represents the formative years of the ‘cinemist' as a documentary maker, photographer and projectionist.

However, the most outstanding experience of the exhibition is probably the recreation of the artist's laboratory in Madrid. Known as PLAT. An acronym for 'Picto-Luminic-Audio-Tactile', it contains his numerous patents and inventions, a true garden of machines. The laboratory was initiated in the late 1970s, when Val del Omar became a widower, and it served him as a space to put his experiments to the test as well as providing a rather monastic home. The ‘cinemist' continued his laser research here, while developing other projects with video and multimedia equipment, including the ultimate focus of his techno-artistic interest, something he named 'Óptica Biónica' (‘bionic optics'). Similar to certain other inventions developed in PLAT, Óptica Biónica, a device with an anamorphic lens and rotating blades, was an attempt to generate volumetric images. Spectators would physically perceive these images as if they were moving around them, while the impression of frame limits disappeared in favour of a seemingly floating screen.

3. The Art of Projection as a Magnetic Field

Last spring I was invited to present a screening of avant-garde films at the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid. This projection was part of a series entitled Archipelago Val del Omar, and its intention was to compliment the exhibition by showing Val del Omar's works alongside other coeval international landmarks of experimental cinema. These screenings made visible the crossroads and contrasts between Val del Omar's filmic experiments and the broader development of the avant-garde.

‘Cinema as Experience: Overflows and Expansions' was the closing event of the series. It included films by Val del Omar, Peter Kubelka and Stan Vanderbeek. These films were selected to frame Val del Omar within the conditions that allow us to call this kind of work ‘paracinema'. That is, works which contribute to the process of the dematerialization of a medium in order to find different, a-disciplinary ways to expand on and continue it. Perhaps the films selected were not the most representative of this but the wider artistic trajectory of the filmmakers included provided the notes of a rich and complex chord that, to my understanding, reveals the context and motivations that transformed cinema into an art of action beyond the black cube.

As I've stated in a previous piece published in this journal (1), I find flicker cinema an essential phenomenon leading to cinema's dematerialization and subsequent expansion into the other arts, and Peter Kubelka's presence in the programme represented this. The Austrian filmmaker, creator of Arnulf Rainer (1954), an orchestration of black and white frames resulting from an exhaustive economy of materials (light, darkness, sound and silence), also designed a theatre venue, now lesser known due to its short existence, in an attempt to improve the conditions of experiencing film. All architectural reference in his ‘Invisible Cinema' (housed in Anthology Film Archives' first building, 1970-1974) was black, and therefore, ‘invisible'. The only remaining point of visual reference in the venue became the screen, while the spectator could accommodate herself to a matrix-like experience of audio-visual immersion.

On the one hand, the ultimate intention of these experiments focused on the transformation of the projection space seems to emerge, as Invisible Cinema demonstrates, as ways to reach the spectator through various physical, corporeal means and to achieve an experience of immersion. On the other hand, if Stan Vanderbeek aspired to reach the human nervous system through more complex technology, Val del Omar's films and writings abound in ideas and techniques such as vibration, pulsation, flicker, palpitation and ecstasy, the ecstasy and tactile potentialities of ‘static images that nonetheless move'. His conference on Óptica Biónica, Ciclo-tactil, is revealing about what I understand as the magnetism of film projection as physical energy, or as Hollis Frampton put it, the fact that none of the arts expresses so thoroughly and complexly the flux of vital breathing as cinema.

Moreover, Val del Omar's ‘systems of commotional communication', subtle interventions and devices arranged in the spectators' seats (including the insertion of electric currents activated by induction, and devices that generated aromas to compliment the film screened), is a clear attempt to penetrate the senses. The Experience Machine, the dream of Vanderbeek that led him to create Movie-Drome (Stony Point, New York, 1965), comprises a similar search: an experience of immersion that functions by prioritizing multisensory perception. Inspired by the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller, Movie-Drome was a spherical theatre in which the audience could lie down and contemplate, from that position, a diversity of films projected on concave screens that commanded the whole visible area.

Cinema could become simultaneously an art of action, a performance or an environment, as well as the critical means to engage with the effects of mass media on the wider social and cultural experience. If images were language, a means of achieving universal communication, Val del Omar and Vanderbeek shared the conviction that technology would sooner or later realize a radical and heterogeneous idea of cinema.

According to Vanderbeek, his experiment's intention was to replace the traditional rigid images of uni-directional screenings, with a new floating and curved experience of the image-movement, an approach that apparently shares some methods with Val del Omar's conception of his mechanical mysticism. Nonetheless, Vanderbeek's project was more ambitious, since the drome was conceived as a prototype for a telecommunications system in which several dromes would be positioned throughout the world linked by an orbiting satellite to transmit images.

In his modest, insular way, Val del Omar imagined the future transformation from a mechanical to a more unifying, electronic information age less enthusiastically than Vanderbeek. Val del Omar felt that the new technologies of the image, and television, were progressing towards a deformed world, and blamed himself for being ‘one of the founders of such collective cretinization'; burning the virginal sensibility for the devil', and, as a last resort, contributing in making art an active accomplice of the banal aesthetization of mass media. Perhaps for this reason, and because ‘gravity force is a curse of which man cannot be liberated but by burning out', Val del Omar, who had dedicated his life to exploring the possibilities of cinematic space, focused almost exclusively on a smaller scale format, Super8, towards the end of his life.

Esperanza Collado

Esperanza Collado is an artist-researcher, and her practice includes film curation, writing, lecturing, performance and filmmaking.

Website: http://www.esperanzacollado.org/

Nema komentara:

Objavi komentar